Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Banking Cases Batch 1

Hochgeladen von

asdfghjkattCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Banking Cases Batch 1

Hochgeladen von

asdfghjkattCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

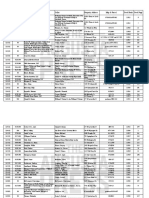

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

GR 880313 simex intl vs ca

118492 reyes vs ca

rp vs security credit L-20583

central bank vs morfe L-20119

BPI family vs franco 123498

bpi vs ca 104612

Vitug vs Ca 82027

BPI vs IAC 206 scra 408

Go vs IAC 197 scra 22 1991

firestone vs ca 113236

PBCom v CA 269 scra 695 1997

salvacion vs CB 94723

rcbc v de castro 168 scra 49

1. Check No. 215391 dated May 29, 1981, in favor of California

Manufacturing Company, Inc. for P16,480.00:

2. Check No. 215426 dated May 28, 1981, in favor of the

Bureau of Internal Revenue in the amount of P3,386.73:

3. Check No. 215451 dated June 4, 1981, in favor of Mr. Greg

Pedreo in the amount of P7,080.00;

4. Check No. 215441 dated June 5, 1981, in favor of Malabon

Longlife Trading Corporation in the amount of P42,906.00:

5. Check No. 215474 dated June 10, 1981, in favor of Malabon

Longlife Trading Corporation in the amount of P12,953.00:

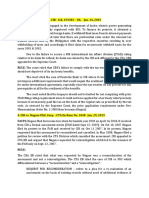

G.R. No. 88013 March 19, 1990

6. Check No. 215477 dated June 9, 1981, in favor of Sea-Land

Services, Inc. in the amount of P27,024.45:

SIMEX INTERNATIONAL (MANILA), INCORPORATED, petitioner,

vs.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and TRADERS ROYAL

BANK, respondents.

7. Check No. 215412 dated June 10, 1981, in favor of Baguio

Country Club Corporation in the amount of P4,385.02: and

CRUZ, J.:

We are concerned in this case with the question of damages, specifically moral

and exemplary damages. The negligence of the private respondent has already

been established. All we have to ascertain is whether the petitioner is entitled to

the said damages and, if so, in what amounts.

The parties agree on the basic facts. The petitioner is a private corporation

engaged in the exportation of food products. It buys these products from various

local suppliers and then sells them abroad, particularly in the United States,

Canada and the Middle East. Most of its exports are purchased by the petitioner

on credit.

The petitioner was a depositor of the respondent bank and maintained a checking

account in its branch at Romulo Avenue, Cubao, Quezon City. On May 25, 1981,

the petitioner deposited to its account in the said bank the amount of P100,000.00,

thus increasing its balance as of that date to P190,380.74. 1 Subsequently, the

petitioner issued several checks against its deposit but was suprised to learn later

that they had been dishonored for insufficient funds.

The dishonored checks are the following:

8. Check No. 215480 dated June 9, 1981, in favor of Enriqueta

Bayla in the amount of P6,275.00. 2

As a consequence, the California Manufacturing Corporation sent on June 9,

1981, a letter of demand to the petitioner, threatening prosecution if the

dishonored check issued to it was not made good. It also withheld delivery of the

order made by the petitioner. Similar letters were sent to the petitioner by the

Malabon Long Life Trading, on June 15, 1981, and by the G. and U. Enterprises,

on June 10, 1981. Malabon also canceled the petitioner's credit line and demanded

that future payments be made by it in cash or certified check. Meantime, action on

the pending orders of the petitioner with the other suppliers whose checks were

dishonored was also deferred.

The petitioner complained to the respondent bank on June 10,

1981. 3 Investigation disclosed that the sum of P100,000.00 deposited by the

petitioner on May 25, 1981, had not been credited to it. The error was rectified on

June 17, 1981, and the dishonored checks were paid after they were redeposited. 4

In its letter dated June 20, 1981, the petitioner demanded reparation from the

respondent bank for its "gross and wanton negligence." This demand was not met.

The petitioner then filed a complaint in the then Court of First Instance of Rizal

claiming from the private respondent moral damages in the sum of P1,000,000.00

and exemplary damages in the sum of P500,000.00, plus 25% attorney's fees, and

costs.

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

After trial, Judge Johnico G. Serquinia rendered judgment holding that moral and

exemplary damages were not called for under the circumstances. However,

observing that the plaintiff's right had been violated, he ordered the defendant to

pay nominal damages in the amount of P20,000.00 plus P5,000.00 attorney's fees

and costs. 5 This decision was affirmed in toto by the respondent court. 6

The respondent court found with the trial court that the private respondent was

guilty of negligence but agreed that the petitioner was nevertheless not entitled to

moral damages. It said:

The essential ingredient of moral damages is proof of bad faith

(De Aparicio vs. Parogurga, 150 SCRA 280). Indeed, there was

the omission by the defendant-appellee bank to credit

appellant's deposit of P100,000.00 on May 25, 1981. But the

bank rectified its records. It credited the said amount in favor of

plaintiff-appellant in less than a month. The dishonored checks

were eventually paid. These circumstances negate any

imputation or insinuation of malicious, fraudulent, wanton and

gross bad faith and negligence on the part of the defendantappellant.

It is this ruling that is faulted in the petition now before us.

This Court has carefully examined the facts of this case and finds that it cannot

share some of the conclusions of the lower courts. It seems to us that the

negligence of the private respondent had been brushed off rather lightly as if it

were a minor infraction requiring no more than a slap on the wrist. We feel it is

not enough to say that the private respondent rectified its records and credited the

deposit in less than a month as if this were sufficient repentance. The error should

not have been committed in the first place. The respondent bank has not even

explained why it was committed at all. It is true that the dishonored checks were,

as the Court of Appeals put it, "eventually" paid. However, this took almost a

month when, properly, the checks should have been paid immediately upon

presentment.

As the Court sees it, the initial carelessness of the respondent bank, aggravated by

the lack of promptitude in repairing its error, justifies the grant of moral damages.

This rather lackadaisical attitude toward the complaining depositor constituted the

gross negligence, if not wanton bad faith, that the respondent court said had not

been established by the petitioner.

We also note that while stressing the rectification made by the respondent bank,

the decision practically ignored the prejudice suffered by the petitioner. This was

simply glossed over if not, indeed, disbelieved. The fact is that the petitioner's

credit line was canceled and its orders were not acted upon pending receipt of

actual payment by the suppliers. Its business declined. Its reputation was

tarnished. Its standing was reduced in the business community. All this was due to

the fault of the respondent bank which was undeniably remiss in its duty to the

petitioner.

Article 2205 of the Civil Code provides that actual or compensatory damages may

be received "(2) for injury to the plaintiff s business standing or commercial

credit." There is no question that the petitioner did sustain actual injury as a result

of the dishonored checks and that the existence of the loss having been established

"absolute certainty as to its amount is not required." 7 Such injury should bolster

all the more the demand of the petitioner for moral damages and justifies the

examination by this Court of the validity and reasonableness of the said claim.

We agree that moral damages are not awarded to penalize the defendant but to

compensate the plaintiff for the injuries he may have suffered. 8 In the case at bar,

the petitioner is seeking such damages for the prejudice sustained by it as a result

of the private respondent's fault. The respondent court said that the claimed losses

are purely speculative and are not supported by substantial evidence, but if failed

to consider that the amount of such losses need not be established with exactitude

precisely because of their nature. Moral damages are not susceptible of pecuniary

estimation. Article 2216 of the Civil Code specifically provides that "no proof of

pecuniary loss is necessary in order that moral, nominal, temperate, liquidated or

exemplary damages may be adjudicated." That is why the determination of the

amount to be awarded (except liquidated damages) is left to the sound discretion

of the court, according to "the circumstances of each case."

From every viewpoint except that of the petitioner's, its claim of moral damages in

the amount of P1,000,000.00 is nothing short of preposterous. Its business

certainly is not that big, or its name that prestigious, to sustain such an extravagant

pretense. Moreover, a corporation is not as a rule entitled to moral damages

because, not being a natural person, it cannot experience physical suffering or

such sentiments as wounded feelings, serious anxiety, mental anguish and moral

shock. The only exception to this rule is where the corporation has a good

reputation that is debased, resulting in its social humiliation. 9

We shall recognize that the petitioner did suffer injury because of the private

respondent's negligence that caused the dishonor of the checks issued by it. The

immediate consequence was that its prestige was impaired because of the

bouncing checks and confidence in it as a reliable debtor was diminished. The

private respondent makes much of the one instance when the petitioner was sued

in a collection case, but that did not prove that it did not have a good reputation

that could not be marred, more so since that case was ultimately settled. 10 It does

not appear that, as the private respondent would portray it, the petitioner is an

unsavory and disreputable entity that has no good name to protect.

Considering all this, we feel that the award of nominal damages in the sum of

P20,000.00 was not the proper relief to which the petitioner was entitled. Under

Article 2221 of the Civil Code, "nominal damages are adjudicated in order that a

right of the plaintiff, which has been violated or invaded by the defendant, may be

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

vindicated or recognized, and not for the purpose of indemnifying the plaintiff for

any loss suffered by him." As we have found that the petitioner has indeed

incurred loss through the fault of the private respondent, the proper remedy is the

award to it of moral damages, which we impose, in our discretion, in the same

amount of P20,000.00.

Now for the exemplary damages.

The pertinent provisions of the Civil Code are the following:

Art. 2229. Exemplary or corrective damages are imposed, by

way of example or correction for the public good, in addition to

the moral, temperate, liquidated or compensatory damages.

Art. 2232. In contracts and quasi-contracts, the court may award

exemplary damages if the defendant acted in a wanton,

fraudulent, reckless, oppressive, or malevolent manner.

The banking system is an indispensable institution in the modern world and plays

a vital role in the economic life of every civilized nation. Whether as mere passive

entities for the safekeeping and saving of money or as active instruments of

business and commerce, banks have become an ubiquitous presence among the

people, who have come to regard them with respect and even gratitude and, most

of all, confidence. Thus, even the humble wage-earner has not hesitated to entrust

his life's savings to the bank of his choice, knowing that they will be safe in its

custody and will even earn some interest for him. The ordinary person, with equal

faith, usually maintains a modest checking account for security and convenience

in the settling of his monthly bills and the payment of ordinary expenses. As for

business entities like the petitioner, the bank is a trusted and active associate that

can help in the running of their affairs, not only in the form of loans when needed

but more often in the conduct of their day-to-day transactions like the issuance or

encashment of checks.

In every case, the depositor expects the bank to treat his account with the utmost

fidelity, whether such account consists only of a few hundred pesos or of millions.

The bank must record every single transaction accurately, down to the last

centavo, and as promptly as possible. This has to be done if the account is to

reflect at any given time the amount of money the depositor can dispose of as he

sees fit, confident that the bank will deliver it as and to whomever he directs. A

blunder on the part of the bank, such as the dishonor of a check without good

reason, can cause the depositor not a little embarrassment if not also financial loss

and perhaps even civil and criminal litigation.

The point is that as a business affected with public interest and because of the

nature of its functions, the bank is under obligation to treat the accounts of its

depositors with meticulous care, always having in mind the fiduciary nature of

their relationship. In the case at bar, it is obvious that the respondent bank was

remiss in that duty and violated that relationship. What is especially deplorable is

that, having been informed of its error in not crediting the deposit in question to

the petitioner, the respondent bank did not immediately correct it but did so only

one week later or twenty-three days after the deposit was made. It bears repeating

that the record does not contain any satisfactory explanation of why the error was

made in the first place and why it was not corrected immediately after its

discovery. Such ineptness comes under the concept of the wanton manner

contemplated in the Civil Code that calls for the imposition of exemplary

damages.

After deliberating on this particular matter, the Court, in the exercise of its

discretion, hereby imposes upon the respondent bank exemplary damages in the

amount of P50,000.00, "by way of example or correction for the public good," in

the words of the law. It is expected that this ruling will serve as a warning and

deterrent against the repetition of the ineptness and indefference that has been

displayed here, lest the confidence of the public in the banking system be further

impaired.

ACCORDINGLY, the appealed judgment is hereby MODIFIED and the private

respondent is ordered to pay the petitioner, in lieu of nominal damages, moral

damages in the amount of P20,000.00, and exemplary damages in the amount of

P50,000.00 plus the original award of attorney's fees in the amount of P5,000.00,

and costs.

SO ORDERED.

SIMEX INTERNATIONAL (MANILA), INCORPORATED, petitioner,

vs.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and TRADERS ROYAL

BANK, respondents.

BOTTOMLINE: You got preexisting 90K and you deposited 100K, but it was not

updated by the bank, 8 checks bounced and you lost business partners. (burn

down the bank? hahaha) Can you demand moral and exemplary damages?

FACTS: We are concerned in this case with the question of damages, specifically

moral and exemplary damages The petitioner is a private corporation engaged in

the exportation of food products. It buys these products from various local

suppliers and then sells them abroad, particularly in the United States, Canada and

the Middle East. Most of its exports are purchased by the petitioner on credit. The

petitioner was a depositor of the respondent bank and maintained a checking

account in its branch at Romulo Avenue, account in the said bank the amount of

P100,000.00, thus increasing its balance as of that date to P190,380.74. , the

petitioner issued several checks against its deposit but was surprised to learn later

that they had been dishonored for insufficient funds. There were 8 dishonored

checks.

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

The California Manufacturing Corporation sent on June 9, 1981, a letter

of demand to the petitioner, threatening prosecution if the dishonored check

issued to it was not made good. . Malabon also canceled the petitioner's credit line

and demanded that future payments be made by it in cash or certified check The

petitioner complained to the respondent bank on June 10, 1981. 3 Investigation

disclosed that the sum of P100,000.00 deposited by the petitioner on May 25,

1981, had not been credited to it. The error was rectified on June 17, 1981, and the

dishonored checks were paid after they were re-deposited , the petitioner

demanded reparation from the respondent bank for its "gross and wanton

negligence." This demand was not met. Court of First Instance of Rizal claiming

from the private respondent moral damages in the sum of P1,000,000.00 and

exemplary damages in the sum of P500,000.00, plus 25% attorney's fees, and

costs.

Judge Johnico G. Serquinia rendered judgment holding that moral and exemplary

damages were not called for under the circumstances. However, observing that the

plaintiff's right had been violated, he ordered the defendant to pay nominal

damages in the amount of P20,000.00 plus P5,000.00 attorney's fees and costs.

The respondent court found with the trial court that the private respondent was

guilty of negligence but agreed that the petitioner was nevertheless not entitled to

moral damages The error should not have been committed in the first place. The

respondent bank has not even explained why it was committed at all. It is true that

the dishonored checks were, as the Court of Appeals put it, "eventually" paid.

However, this took almost a month when, properly, the checks should have been

paid immediately upon presentment.

ISSUE: After all that you went through, the judge only awarded you 20k and 5k,

can you demand for 1,000,000 damage?

RULING:

We also note that while stressing the rectification made by the respondent bank,

the decision practically ignored the prejudice suffered by the petitioner. Article

2205 of the Civil Code provides that actual or compensatory damages may be

received "(2) for injury to the plaintiff s business standing or commercial credit."

We agree that moral damages are not awarded to penalize the defendant but to

compensate the plaintiff for the injuries he may have suffered From every

viewpoint except that of the petitioner's, its claim of moral damages in the amount

of P1,000,000.00 is nothing short of preposterous. Its business certainly is not that

big, or its name that prestigious, to sustain such an extravagant pretense

Considering all this, we feel that the award of nominal damages in the sum of

P20,000.00 was not the proper relief to which the petitioner was entitled. Under

Article 2221 of the Civil Code, "nominal damages are adjudicated in order that a

right of the plaintiff, which has been violated or invaded by the defendant, may be

vindicated or recognized, and not for the purpose of indemnifying the plaintiff for

any loss suffered by him." the proper remedy is the award to it of moral damages,

which we impose, in our discretion, in the same amount of P20,000.00.

After deliberating on this particular matter, the Court, in the exercise of its

discretion, hereby imposes upon the respondent bank exemplary damages in the

amount of P50,000.00, ACCORDINGLY, the appealed judgment is hereby

MODIFIED and the private respondent is ordered to pay the petitioner, in lieu of

nominal damages, moral damages in the amount of P20,000.00, and exemplary

damages in the amount of P50,000.00 plus the original award of attorney's fees in

the amount of P5,000.00, and costs.

SECOND DIVISION

[G.R. No. 118492. August 15, 2001]

GREGORIO H. REYES and CONSUELO PUYAT-REYES, petitioners,

vs. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS and FAR EAST BANK AND

TRUST COMPANY,respondents.

DECISION

DE LEON, JR., J.:

Before us is a petition for review of the Decision[1] dated July 22, 1994 and

Resolution[2] dated December 29, 1994 of the Court of Appeals [3] affirming with

modification the Decision[4] dated November 12, 1992 of the Regional Trial Court

of Makati, Metro Manila, Branch 64, which dismissed the complaint for damages

of petitioners spouses Gregorio H. Reyes and Consuelo Puyat-Reyes against

respondent Far East Bank and Trust Company.

The undisputed facts of the case are as follows:

In view of the 20th Asian Racing Conference then scheduled to be held in

September, 1988 in Sydney, Australia, the Philippine Racing Club, Inc. (PRCI,

for brevity) sent four (4) delegates to the said conference. Petitioner Gregorio H.

Reyes, as vice-president for finance, racing manager, treasurer, and director of

PRCI, sent Godofredo Reyes, the clubs chief cashier, to the respondent bank to

apply for a foreign exchange demand draft in Australian dollars.

Godofredo went to respondent banks Buendia Branch in Makati City to

apply for a demand draft in the amount One Thousand Six Hundred Ten

Australian Dollars (AU$1,610.00) payable to the order of the 20 th Asian Racing

Conference Secretariat of Sydney, Australia. He was attended to by respondent

banks assistant cashier, Mr. Yasis, who at first denied the application for the

reason that respondent bank did not have an Australian dollar account in any bank

in Sydney. Godofredo asked if there could be a way for respondent bank to

accommodate PRCIs urgent need to remit Australian dollars to Sydney. Yasis of

respondent bank then informed Godofredo of a roundabout way of effecting the

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

requested remittance to Sydney thus: the respondent bank would draw a demand

draft against Westpac Bank in Sydney, Australia (Westpac-Sydney for brevity)

and have the latter reimburse itself from the U.S. dollar account of the respondent

in Westpac Bank in New York, U.S.A (Westpac-New York for brevity). This

arrangement has been customarily resorted to since the 1960s and the procedure

has proven to be problem-free. PRCI and the petitioner Gregorio H. Reyes, acting

through Godofredo, agreed to this arrangement or approach in order to effect the

urgent transfer of Australian dollars payable to the Secretariat of the 20 th Asian

Racing Conference.

On July 28, 1988, the respondent bank approved the said application of

PRCI and issued Foreign Exchange Demand Draft (FXDD) No. 209968 in the

sum applied for, that is, One Thousand Six Hundred Ten Australian Dollars

(AU$1,610.00), payable to the order of the 20 th Asian Racing Conference

Secretariat of Sydney, Australia, and addressed to Westpac-Sydney as the drawee

bank.

On August 10, 1988, upon due presentment of the foreign exchange demand

draft, denominated as FXDD No. 209968, the same was dishonored, with the

notice of dishonor stating the following: xxx No account held with Westpac.

Meanwhile, on August 16, 1988, Westpac-New York sent a cable to respondent

bank informing the latter that its dollar account in the sum of One Thousand Six

Hundred Ten Australian Dollars (AU$1,610.00) was debited. On August 19,

1988, in response to PRCIs complaint about the dishonor of the said foreign

exchange demand draft, respondent bank informed Westpac-Sydney of the

issuance of the said demand draft FXDD No. 209968, drawn against the WestpacSydney and informing the latter to be reimbursed from the respondent banks

dollar account in Westpac-New York. The respondent bank on the same day

likewise informed Westpac-New York requesting the latter to honor the

reimbursement claim of Westpac-Sydney. On September 14, 1988, upon its

second presentment for payment, FXDD No. 209968 was again dishonored by

Westpac-Sydney for the same reason, that is, that the respondent bank has no

deposit dollar account with the drawee Westpac-Sydney.

On September 17, 1988 and September 18, 1988, respectively, petitioners

spouses Gregorio H. Reyes and Consuelo Puyat-Reyes left for Australia to attend

the said racing conference. When petitioner Gregorio H. Reyes arrived in Sydney

in the morning of September 18, 1988, he went directly to the lobby of Hotel

Regent Sydney to register as a conference delegate. At the registration desk, in the

presence of other delegates from various member countries, he was told by a lady

member of the conference secretariat that he could not register because the foreign

exchange demand draft for his registration fee had been dishonored for the second

time. A discussion ensued in the presence and within the hearing of many

delegates who were also registering. Feeling terribly embarrassed and humiliated,

petitioner Gregorio H. Reyes asked the lady member of the conference secretariat

that he be shown the subject foreign exchange demand draft that had been

dishonored as well as the covering letter after which he promised that he would

pay the registration fees in cash. In the meantime he demanded that he be given

his name plate and conference kit. The lady member of the conference secretariat

relented and gave him his name plate and conference kit. It was only two (2) days

later, or on September 20, 1988, that he was given the dishonored demand draft

and a covering letter. It was then that he actually paid in cash the registration fees

as he had earlier promised.

Meanwhile, on September 19, 1988, petitioner Consuelo Puyat-Reyes

arrived in Sydney. She too was embarrassed and humiliated at the registration

desk of the conference secretariat when she was told in the presence and within

the hearing of other delegates that she could not be registered due to the dishonor

of the subject foreign exchange demand draft. She felt herself trembling and

unable to look at the people around her. Fortunately, she saw her husband coming

toward her. He saved the situation for her by telling the secretariat member that he

had already arranged for the payment of the registration fees in cash once he was

shown the dishonored demand draft. Only then was petitioner Puyat-Reyes given

her name plate and conference kit.

At the time the incident took place, petitioner Consuelo Puyat-Reyes was a

member of the House of Representatives representing the lone Congressional

District of Makati, Metro Manila. She has been an officer of the Manila Banking

Corporation and was cited by Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin as the top lady

banker of the year in connection with her conferment of the Pro-Ecclesia et

Pontifice Award. She has also been awarded a plaque of appreciation from the

Philippine Tuberculosis Society for her extraordinary service as the Societys

campaign chairman for the ninth (9th) consecutive year.

On November 23, 1988, the petitioners filed in the Regional Trial Court of

Makati, Metro Manila, a complaint for damages, docketed as Civil Case No. 882468, against the respondent bank due to the dishonor of the said foreign

exchange demand draft issued by the respondent bank. The petitioners claim that

as a result of the dishonor of the said demand draft, they were exposed to

unnecessary shock, social humiliation, and deep mental anguish in a foreign

country, and in the presence of an international audience.

On November 12, 1992, the trial court rendered judgment in favor of the

defendant (respondent bank) and against the plaintiffs (herein petitioners), the

dispositive portion of which states:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of the defendant, dismissing

plaintiffs complaint, and ordering plaintiffs to pay to defendant, on its

counterclaim, the amount of P50,000.00, as reasonable attorneys fees. Costs

against the plaintiff.

SO ORDERED.[5]

The petitioners appealed the decision of the trial court to the Court of

Appeals. On July 22, 1994, the appellate court affirmed the decision of the trial

court but in effect deleted the award of attorneys fees to the defendant (herein

respondent bank) and the pronouncement as to the costs. The decretal portion of

the decision of the appellate court states:

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

WHEREFORE, the judgment appealed from, insofar as it dismisses plaintiffs

complaint, is hereby AFFIRMED, but is hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE in

all other respect. No special pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.[6]

According to the appellate court, there is no basis to hold the respondent

bank liable for damages for the reason that it exerted every effort for the subject

foreign exchange demand draft to be honored.The appellate court found and

declared that:

xxx xxx xxx

Thus, the Bank had every reason to believe that the transaction finally went

through smoothly, considering that its New York account had been debited and

that there was no miscommunication between it and Westpac-New York. SWIFT

is a world wide association used by almost all banks and is known to be the most

reliable mode of communication in the international banking business. Besides,

the above procedure, with the Bank as drawer and Westpac-Sydney as drawee,

and with Westpac-New York as the reimbursement Bank had been in place since

1960s and there was no reason for the Bank to suspect that this particular demand

draft would not be honored by Westpac-Sydney.

From the evidence, it appears that the root cause of the miscommunications of the

Banks SWIFT message is the erroneous decoding on the part of Westpac-Sydney

of the Banks SWIFT message as an MT799 format. However, a closer look at the

Banks Exhs. 6 and 7 would show that despite what appears to be an asterisk

written over the figure before 99, the figure can still be distinctly seen as a number

1 and not number 7, to the effect that Westpac-Sydney was responsible for the

dishonor and not the Bank.

Moreover, it is not said asterisk that caused the misleading on the part of the

Westpac-Sydney of the numbers 1 to 7, since Exhs. 6 and 7 are just documentary

copies of the cable message sent to Westpac-Sydney. Hence, if there was mistake

committed by Westpac-Sydney in decoding the cable message which caused the

Banks message to be sent to the wrong department, the mistake was Westpacs, not

the Banks. The Bank had done what an ordinary prudent person is required to do

in the particular situation, although appellants expect the Bank to have done more.

The Bank having done everything necessary or usual in the ordinary course of

banking transaction, it cannot be held liable for any embarrassment and

corresponding damage that appellants may have incurred.[7]

xxx xxx xxx

Hence, this petition, anchored on the following assignment of errors:

I

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN FINDING

PRIVATE RESPONDENT NOT NEGLIGENT BY ERRONEOUSLY

APPLYING THE STANDARD OF DILIGENCE OF AN ORDINARY

PRUDENT PERSON WHEN IN TRUTH A HIGHER DEGREE OF

DILIGENCE IS IMPOSED BY LAW UPON THE BANKS.

II

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN ABSOLVING

PRIVATE RESPONDENT FROM LIABILITY BY OVERLOOKING THE

FACT THAT THE DISHONOR OF THE DEMAND DRAFT WAS A

BREACH OF PRIVATE RESPONDENTS WARRANTY AS THE

DRAWER THEREOF.

III

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN NOT HOLDING

THAT AS SHOWN OVERWHELMINGLY BY THE EVIDENCE, THE

DISHONOR OF THE DEMAND DRAFT WAS DUE TO PRIVATE

RESPONDENTS NEGLIGENCE AND NOT THE DRAWEE BANK. [8]

The petitioners contend that due to the fiduciary nature of the relationship

between the respondent bank and its clients, the respondent bank should have

exercised a higher degree of diligence than that expected of an ordinary prudent

person in the handling of its affairs as in the case at bar. The appellate court,

according to petitioners, erred in applying the standard of diligence of an ordinary

prudent person only. Petitioners also claim that the respondent bank violated

Section 61 of the Negotiable Instruments Law[9] which provides the warranty of a

drawer that xxx on due presentment, the instrument will be accepted or paid, or

both, according to its tenor xxx. Thus, the petitioners argue that respondent bank

should be held liable for damages for violation of this warranty. The petitioners

pray this Court to re-examine the facts to cite certain instances of negligence.

It is our view and we hold that there is no reversible error in the decision of

the appellate court.

Section 1 of Rule 45 of the Revised Rules of Court provides that (T)he

petition (for review) shall raise only questions of law which must be distinctly set

forth. Thus, we have ruled that factual findings of the Court of Appeals are

conclusive on the parties and not reviewable by this Court and they carry even

more weight when the Court of Appeals affirms the factual findings of the trial

court.[10]

The courts a quo found that respondent bank did not misrepresent that it was

maintaining a deposit account with Westpac-Sydney. Respondent banks assistant

cashier explained to Godofredo Reyes, representating PRCI and petitioner

Gregorio H. Reyes, how the transfer of Australian dollars would be effected

through Westpac-New York where the respondent bank has a dollar account to

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

Westpac-Sydney where the subject foreign exchange demand draft (FXDD No.

209968) could be encashed by the payee, the 20 th Asian Racing Conference

Secretatriat. PRCI and its Vice-President for finance, petitioner Gregorio H.

Reyes, through their said representative, agreed to that arrangement or

procedure. In other words, the petitioners are estopped from denying the said

arrangement or procedure. Similar arrangements have been a long standing

practice in banking to facilitate international commercial transactions. In fact, the

SWIFT cable message sent by respondent bank to the drawee bank, WestpacSydney, stated that it may claim reimbursement from its New York branch,

Westpac-New York where respondent bank has a deposit dollar account.

The facts as found by the courts a quo show that respondent bank did not

cause an erroneous transmittal of its SWIFT cable message to Westpac-Sydney. It

was the erroneous decoding of the cable message on the part of Westpac-Sydney

that caused the dishonor of the subject foreign exchange demand draft. An

employee of Westpac-Sydney in Sydney, Australia mistakenly read the printed

figures in the SWIFT cable message of respondent bank as MT799 instead of as

MT199. As a result, Westpac-Sydney construed the said cable message as a

format for a letter of credit, and not for a demand draft. The appellate court

correctly found that the figure before 99 can still be distinctly seen as a number 1

and not number 7. Indeed, the line of a 7 is in a slanting position while the line of

a 1 is in a horizontal position. Thus, the number 1 in MT199 cannot be construed

as 7.[11]

The evidence also shows that the respondent bank exercised that degree of

diligence expected of an ordinary prudent person under the circumstances

obtaining. Prior to the first dishonor of the subject foreign exchange demand draft,

the respondent bank advised Westpac-New York to honor the reimbursement

claim of Westpac-Sydney and to debit the dollar account[12] of respondent bank

with the former.As soon as the demand draft was dishonored, the respondent

bank, thinking that the problem was with the reimbursement and without any idea

that it was due to miscommunication, re-confirmed the authority of Westpac-New

York to debit its dollar account for the purpose of reimbursing WestpacSydney.[13] Respondent bank also sent two (2) more cable messages to WestpacNew York inquiring why the demand draft was not honored.[14]

With these established facts, we now determine the degree of diligence that

banks are required to exert in their commercial dealings. In Philippine Bank of

Commerce v. Court of Appeals[15] upholding a long standing doctrine, we ruled

that the degree of diligence required of banks, is more than that of a good father of

a family where the fiduciary nature of their relationship with their depositors is

concerned.In other words banks are duty bound to treat the deposit accounts of

their depositors with the highest degree of care. But the said ruling applies only to

cases where banks act under their fiduciary capacity, that is, as depositary of the

deposits of their depositors. But the same higher degree of diligence is not

expected to be exerted by banks in commercial transactions that do not involve

their fiduciary relationship with their depositors.

Considering the foregoing, the respondent bank was not required to exert

more than the diligence of a good father of a family in regard to the sale and

issuance of the subject foreign exchange demand draft. The case at bar does not

involve the handling of petitioners deposit, if any, with the respondent

bank. Instead, the relationship involved was that of a buyer and seller, that is,

between the respondent bank as the seller of the subject foreign exchange demand

draft, and PRCI as the buyer of the same, with the 20 th Asian Racing Conference

Secretariat in Sydney, Australia as the payee thereof. As earlier mentioned, the

said foreign exchange demand draft was intended for the payment of the

registration fees of the petitioners as delegates of the PRCI to the 20 th Asian

Racing Conference in Sydney.

The evidence shows that the respondent bank did everything within its

power to prevent the dishonor of the subject foreign exchange demand draft. The

erroneous reading of its cable message to Westpac-Sydney by an employee of the

latter could not have been foreseen by the respondent bank. Being unaware that its

employee erroneously read the said cable message, Westpac-Sydney merely stated

that the respondent bank has no deposit account with it to cover for the amount of

One Thousand Six Hundred Ten Australian Dollar (AU$1610.00) indicated in the

foreign exchange demand draft. Thus, the respondent bank had the impression

that Westpac-New York had not yet made available the amount for reimbursement

to Westpac-Sydney despite the fact that respondent bank has a sufficient deposit

dollar account with Westpac-New York. That was the reason why the respondent

bank had to re-confirm and repeatedly notify Westpac-New York to debit its

(respondent banks) deposit dollar account with it and to transfer or credit the

corresponding amount to Westpac-Sydney to cover the amount of the said demand

draft.

In view of all the foregoing, and considering that the dishonor of the subject

foreign exchange demand draft is not attributable to any fault of the respondent

bank, whereas the petitioners appeared to be under estoppel as earlier mentioned,

it is no longer necessary to discuss the alleged application of Section 61 of the

Negotiable Instruments Law to the case at bar. In any event, it was established

that the respondent bank acted in good faith and that it did not cause the

embarrassment of the petitioners in Sydney, Australia. Hence, the Court of

Appeals did not commit any reversable error in its challenged decision.

WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby DENIED, and the assailed decision

of the Court of Appeals is AFFIRMED. Costs against the petitioners.

SO ORDERED.

Reyes VS. CA

Facts: By virtue of the erroneous reading of the cable message by its employee,

Westpac- Sydney asserted that the respondent Bank had no deposit account with it

to cover for the amount of AU$1610.00 indicated in the foreign exchange demand

draft. Consequently, the respondent Bank had the impression that Westpac- New

York had not yet made available the amount for reimbursement to Westpac

Sidney despite the fact that Respondent Bank has a sufficient deposit dollar

account with Westpac New York. Nevertheless, the demand draft was not

served. Can the Respondent Bank be held liable?

Held: No, when the circumstances show that all efforts were made by the

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

respondent bank to avoid such mistakes.

In Phil. Bank of Commerce v. CA, upholding a long standing doctrine, it was

ruled that the degree of diligence required of bank is more than that of good father

of a family, where the fiduciary nature of their relationship with their depositors is

concerned. In other words, banks are duty bound to test the deposit accounts of

their depositors. But the same higher degree of diligence is not expected to be

executed by banks in commercial instruction that do not involve their fiduciary

relationship with their depositors.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-20583

January 23, 1967

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, petitioner,

vs.

SECURITY CREDIT AND ACCEPTANCE CORPORATION, ROSENDO

T. RESUELLO, PABLO TANJUTCO, ARTURO SORIANO, RUBEN

BELTRAN, BIENVENIDO V. ZAPA, PILAR G. RESUELLO, RICARDO D.

BALATBAT, JOSE SEBASTIAN and VITO TANJUTCO JR., respondents.

Office of the Solicitor General Arturo A. Alafriz and Solicitor E. M. Salva for

petitioner.

Sycip, Salazar, Luna, Manalo & Feliciano for respondents.

Natalio M. Balboa and F. E. Evangelista for the receiver.

CONCEPCION, C.J.:

This is an original quo warranto proceeding, initiated by the Solicitor General, to

dissolve the Security and Acceptance Corporation for allegedly engaging in

banking operations without the authority required therefor by the General Banking

Act (Republic Act No. 337). Named as respondents in the petition are, in addition

to said corporation, the following, as alleged members of its Board of Directors

and/or Executive Officers, namely:

NAME

Pablo Tanjutco

Director

Arturo Soriano

Director

Ruben Beltran

Director

Bienvenido V. Zapa

Director & Vice-President

Pilar G. Resuello

Director & Secretary-Treasurer

Ricardo D. Balatbat

Director & Auditor

Jose R. Sebastian

Director & Legal Counsel

Vito Tanjutco Jr.

Director & Personnel Manager

The record shows that the Articles of Incorporation of defendant

corporation1 were registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission on

March 27, 1961; that the next day, the Board of Directors of the corporation

adopted a set of by-laws,2 which were filed with said Commission on April 5,

1961; that on September 19, 1961, the Superintendent of Banks of the Central

Bank of the Philippines asked its legal counsel an opinion on whether or not said

corporation is a banking institution, within the purview of Republic Act No. 337;

that, acting upon this request, on October 11, 1961, said legal counsel rendered an

opinion resolving the query in the affirmative; that in a letter, dated January 15,

1962, addressed to said Superintendent of Banks, the corporation through its

president, Rosendo T. Resuello, one of defendants herein, sought a

reconsideration of the aforementioned opinion, which reconsideration was denied

on March 16, 1962; that, prior thereto, or on March 9, 1961, the corporation had

applied with the Securities and Exchange Commission for the registration and

licensing of its securities under the Securities Act; that, before acting on this

application, the Commission referred it to the Central Bank, which, in turn, gave

the former a copy of the above-mentioned opinion, in line with which, the

Commission advised the corporation on December 5, 1961, to comply with the

requirements of the General Banking Act; that, upon application of members of

the Manila Police Department and an agent of the Central Bank, on May 18, 1962,

the Municipal Court of Manila issued Search Warrant No. A-1019; that, pursuant

thereto, members of the intelligence division of the Central Bank and of the

Manila Police Department searched the premises of the corporation and seized

documents and records thereof relative to its business operations; that, upon the

return of said warrant, the seized documents and records were, with the authority

of the court, placed under the custody of the Central Bank of the Philippines; that,

upon examination and evaluation of said documents and records, the intelligence

division of the Central Bank submitted, to the Acting Deputy Governor thereof, a

memorandum dated September 10, 1962, finding that the corporation is:

POSITION

Rosendo T. Resuello President & Chairman of the Board

1. Performing banking functions, without requisite certificate of authority

from the Monetary Board of the Central Bank, in violation of Secs. 2 and

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

6 of Republic Act 337, in that it is soliciting and accepting deposit from

the public and lending out the funds so received;

2. Soliciting and accepting savings deposits from the general

public when the company's articles of incorporation authorize it only to

engage primarily in financing agricultural, commercial and industrial

projects, and secondarily, in buying and selling stocks and bonds of any

corporation, thereby exceeding the scope of its powers and authority as

granted under its charter; consequently such acts are ultra-vires:

3. Soliciting subscriptions to the corporate shares of stock and accepting

deposits on account thereof, without prior registration and/or licensing

of such shares or securing exemption therefor, in violation of the

Securities Act; and

4. That being a private credit and financial institution, it should come

under the supervision of the Monetary Board of the Central Bank, by

virtue of the transfer of the authority, power, duties and functions of the

Secretary of Finance, Bank Commissioner and the defunct Bureau of

Banking, to the said Board, pursuant to Secs. 139 and 140 of Republic

Act 265 and Secs. 88 and 89 of Republic Act 337." (Emphasis Supplied.)

that upon examination and evaluation of the same records of the

corporation, as well as of other documents and pertinent pipers obtained

elsewhere, the Superintendent of Banks, submitted to the Monetary

Board of the Central Bank a memorandum dated August 28, 1962,

stating inter alia.

11. Pursuant to the request for assistance by the Chief, Intelligence

Division, contained in his Memorandum to the Governor dated May 23,

1962 and in accordance with the written instructions of Governor

Castillo dated May 31, 1962, an examination of the books and records of

the Security Credit and Loans Organizations, Inc. seized by the

combined MPD-CB team was conducted by this Department. The

examination disclosed the following findings:

a. Considering the extent of its operations, the Security Credit

and Acceptance Corporation, Inc.,receives deposits from the

public regularly. Such deposits are treated in the Corporation's

financial statements as conditional subscription to capital stock.

Accumulated deposits of P5,000 of an individual depositor may

be converted into stock subscription to the capital stock of the

Security Credit and Acceptance Corporation at the option of the

depositor. Sale of its shares of stock or subscriptions to its

capital stock are offered to the public as part of its regular

operations.

b. That out of the funds obtained from the public through the

receipt of deposits and/or the sale of securities, loans are made

regularly to any person by the Security Credit and Acceptance

Corporation.

A copy of the Memorandum Report dated July 30, 1962 of the

examination made by Examiners of this Department of the seized books

and records of the Corporation is attached hereto.

12. Section 2 of Republic Act No. 337, otherwise known as the General

Banking Act, defines the term, "banking institution" as follows:

Sec. 2. Only duly authorized persons and entities may engage in

the lending of funds obtained from the public through the

receipts of deposits or the sale of bonds, securities, or

obligations of any kind and all entities regularly conducting

operations shall be considered as banking institutions and shall

be subject to the provisions of this Act, of the Central Bank Act,

and of other pertinent laws. ...

13. Premises considered, the examination disclosed that the Security

Credit and Acceptance Corporation isregularly lending funds obtained

from the receipt of deposits and/or the sale of securities. The

Corporation therefore is performing 'banking functions' as contemplated

in Republic Act No. 337, without having first complied with the

provisions of said Act.

Recommendations:

In view of all the foregoing, it is recommended that the Monetary Board

decide and declare:

1. That the Security Credit and Acceptance Corporation is performing

banking functions without having first complied with the provisions of

Republic Act No. 337, otherwise known as the General Banking Act, in

violation of Sections 2 and 6 thereof; and

2. That this case be referred to the Special Assistant to the Governor

(Legal Counsel) for whatever legal actions are warranted, including, if

warranted criminal action against the Persons criminally liable and/orquo

warranto proceedings with preliminary injunction against the

Corporation for its dissolution. (Emphasis supplied.)

that, acting upon said memorandum of the Superintendent of Banks, on

September 14, 1962, the Monetary Board promulgated its Resolution No.

1095, declaring that the corporation is performing banking operations,

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

without having first complied with the provisions of Sections 2 and 6 of

Republic Act No. 337;3that on September 25, 1962, the corporation was

advised of the aforementioned resolution, but, this notwithstanding, the

corporation, as well as the members of its Board of Directors and the

officers of the corporation, have been and still are performing the

functions and activities which had been declared to constitute illegal

banking operations; that during the period from March 27, 1961 to May

18, 1962, the corporation had established 74 branches in principal cities

and towns throughout the Philippines; that through a systematic and

vigorous campaign undertaken by the corporation, the same had

managed to induce the public to open 59,463 savings deposit accounts

with an aggregate deposit of P1,689,136.74; that, in consequence of the

foregoing deposits with the corporation, its original capital stock of

P500,000, divided into 20,000 founders' shares of stock and 80,000

preferred shares of stock, both of which had a par value of P5.00 each,

was increased, in less than one (1) year, to P3,000,000 divided into

130,000 founders' shares and 470,000 preferred shares, both with a par

value of P5.00 each; and that, according to its statement of assets and

liabilities, as of December 31, 1961, the corporation had a capital stock

aggregating P1,273,265.98 and suffered, during the year 1961, a loss of

P96,685.29. Accordingly, on December 6, 1962, the Solicitor General

commenced this quo warranto proceedings for the dissolution of the

corporation, with a prayer that, meanwhile, a writ of preliminary

injunction be issued ex parte, enjoining the corporation and its branches,

as well as its officers and agents, from performing the banking operations

complained of, and that a receiver be appointed pendente lite.

Upon joint motion of both parties, on August 20, 1963, the Superintendent of

Banks of the Central Bank of the Philippines was appointed by this Court receiver

pendente lite of defendant corporation, and upon the filing of the requisite bond,

said officer assumed his functions as such receiver on September 16, 1963.

defendants Rosendo T. Resullo, Zapa, Pilar G. Resuello, Balatbat and Sebastian as

proposed president, vice-president, secretary-treasurer, auditor and legal counsel,

respectively; that said additional officers had never assumed their respective

offices because of the pendency of the approval of said application for conversion;

that defendants Soriano, Beltran, Sebastian, Vito Tanjutco Jr. and Pablo Tanjutco

had subsequently withdrawn from the proposed mortgage and savings bank; that

on November 29, 1962 or before the commencement of the present

proceedings the corporation and defendants Rosendo T. Resuello and Pilar G.

Resuello had instituted Civil Case No. 52342 of the Court of First Instance of

Manila against Purificacion Santos and other members of the savings plan of the

corporation and the City Fiscal for a declaratory relief and an injunction; that on

December 3, 1962, Judge Gaudencio Cloribel of said court issued a writ directing

the defendants in said case No. 52342 and their representatives or agents to refrain

from prosecuting the plaintiff spouses and other officers of the corporation by

reason of or in connection with the acceptance by the same of deposits under its

savings plan; that acting upon a petition filed by plaintiffs in said case No. 52342,

on December 6, 1962, the Court of First Instance of Manila had appointed Jose

Ma. Ramirez as receiver of the corporation; that, on December 12, 1962, said

Ramirez qualified as such receiver, after filing the requisite bond; that, except as

to one of the defendants in said case No. 52342, the issues therein have already

been joined; that the failure of the corporation to honor the demands for

withdrawal of its depositors or members of its savings plan and its former

employees was due, not to mismanagement or misappropriation of corporate

funds, but to an abnormal situation created by the mass demand for withdrawal of

deposits, by the attachment of property of the corporation by its creditors, by the

suspension by debtors of the corporation of the payment of their debts thereto and

by an order of the Securities and Exchange Commission dated September 26,

1962, to the corporation to stop soliciting and receiving deposits; and that the

withdrawal of deposits of members of the savings plan of the corporation was

understood to be subject, as to time and amounts, to the financial condition of the

corporation as an investment firm.

In their answer, defendants admitted practically all of the allegations of fact made

in the petition. They, however, denied that defendants Tanjutco (Pablo and Vito,

Jr.), Soriano, Beltran, Zapa, Balatbat and Sebastian, are directors of the

corporation, as well as the validity of the opinion, ruling, evaluation and

conclusions, rendered, made and/or reached by the legal counsel and the

intelligence division of the Central Bank, the Securities and Exchange

Commission, and the Superintendent of Banks of the Philippines, or in Resolution

No. 1095 of the Monetary Board, or of Search Warrant No. A-1019 of the

Municipal Court of Manila, and of the search and seizure made thereunder. By

way of affirmative allegations, defendants averred that, as of July 7, 1961, the

Board of Directors of the corporation was composed of defendants Rosendo T.

Resuello, Aquilino L. Illera and Pilar G. Resuello; that on July 11, 1962, the

corporation had filed with the Superintendent of Banks an application for

conversion into a Security Savings and Mortgage Bank, with defendants Zapa,

Balatbat, Tanjutco (Pablo and Vito, Jr.), Soriano, Beltran and Sebastian as

proposed directors, in addition to the defendants first named above, with

In its reply, plaintiff alleged that a photostat copy, attached to said pleading, of the

anniversary publication of defendant corporation showed that defendants Pablo

Tanjutco, Arturo Soriano, Ruben Beltran, Bienvenido V. Zapa, Ricardo D.

Balatbat, Jose R. Sebastian and Vito Tanjutco Jr. are officers and/or directors

thereof; that this is confirmed by the minutes of a meeting of stockholders of the

corporation, held on September 27, 1962, showing that said defendants had been

elected officers thereof; that the views of the legal counsel of the Central Bank, of

the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Intelligence Division, the

Superintendent of Banks and the Monetary Board above referred to have been

expressed in the lawful performance of their respective duties and have not been

assailed or impugned in accordance with law; that neither has the validity of

Search Warrant No. A-1019 been contested as provided by law; that the only

assets of the corporation now consist of accounts receivable amounting

approximately to P500,000, and its office equipment and appliances, despite its

increased capitalization of P3,000,000 and its deposits amounting to not less than

P1,689,136.74; and that the aforementioned petition of the corporation, in Civil

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

Case No. 52342 of the Court of First Instance of Manila, for a declaratory relief is

now highly improper, the defendants having already committed infractions and

violations of the law justifying the dissolution of the corporation.

Although, admittedly, defendant corporation has not secured the requisite

authority to engage in banking, defendants deny that its transactions partake of the

nature of banking operations. It is conceded, however, that, in consequence of a

propaganda campaign therefor, a total of 59,463 savings account deposits have

been made by the public with the corporation and its 74 branches, with an

aggregate deposit of P1,689,136.74, which has been lent out to such persons as

the corporation deemed suitable therefor. It is clear that these transactions partake

of the nature of banking, as the term is used in Section 2 of the General Banking

Act. Indeed, a bank has been defined as:

jurisdiction, concurrently with courts of first instance, to hear and decide quo

warranto cases and, that, consequently, it is discretionary for us to entertain the

present case or to require that the issues therein be taken up in said Civil Case No.

52342. The Veraguth case cited by herein defendants, in support of the second

alternative, is not in point, because in said case there were issues of fact which

required the presentation of evidence, and courts of first instance are, in general,

better equipped than appellate courts for the taking of testimony and the

determination of questions of fact. In the case at bar, there is, however, no dispute

as to the principal facts or acts performed by the corporation in the conduct of its

business. The main issue here is one of law, namely, the legal nature of said facts

or of the aforementioned acts of the corporation. For this reason, and because

public interest demands an early disposition of the case, we have deemed it best to

determine the merits thereof.

... a moneyed institute [Talmage vs. Pell 7 N.Y. (3 Seld. ) 328, 347, 348]

founded to facilitate the borrowing, lending and safe-keeping of money

(Smith vs. Kansas City Title & Trust Co., 41 S. Ct. 243, 255 U.S. 180,

210, 65 L. Ed. 577) and to deal, in notes, bills of exchange, and credits

(State vs. Cornings Sav. Bank, 115 N.W. 937, 139 Iowa 338). (Banks &

Banking, by Zellmann Vol. 1, p. 46).

Wherefore, the writ prayed for should be, as it is hereby granted and defendant

corporation is, accordingly, ordered dissolved. The appointment of receiver herein

issued pendente lite is hereby made permanent, and the receiver is, accordingly,

directed to administer the properties, deposits, and other assets of defendant

corporation and wind up the affairs thereof conformably to Rules 59 and 66 of the

Rules of Court. It is so ordered.

Moreover, it has been held that:

An investment company which loans out the money of its customers,

collects the interest and charges a commission to both lender and

borrower, is a bank. (Western Investment Banking Co. vs. Murray, 56 P.

728, 730, 731; 6 Ariz 215.)

Republic of the Philippines vs. Security Credit and Acceptance Corporation G.R.

No. L-20583, January 23, 1967

MARCH 16, 2014LEAVE A COMMENT

An investment company which loans out the money of its customers, collects the

interest and charges a commission to both lender and borrower, is a bank. It is

... any person engaged in the business carried on by banks of deposit, of

discount, or of circulation is doing a banking business, although but one

of these functions is exercised. (MacLaren vs. State, 124 N.W. 667, 141

Wis. 577, 135 Am. S.R. 55, 18 Ann. Cas. 826; 9 C.J.S. 30.)

conceded that a total of 59,463 savings account deposits have been made by the

Accordingly, defendant corporation has violated the law by engaging in

banking without securing the administrative authority required in

Republic Act No. 337.

deemed suitable therefore. It is clear that these transactions partake of the

public with the corporation and its 74 branches, with an aggregate deposit of

P1,689,136.74, which has been lent out to such persons as the corporation

nature of banking, as the term is used in Section 2 of the General Banking Act.

Facts: The Solicitor General filed a petition for quo warranto to dissolve the

That the illegal transactions thus undertaken by defendant corporation warrant its

dissolution is apparent from the fact that the foregoing misuser of the corporate

funds and franchise affects the essence of its business, that it is willful and has

been repeated 59,463 times, and that its continuance inflicts injury upon the

public, owing to the number of persons affected thereby.

It is urged, however, that this case should be remanded to the Court of First

Instance of Manila upon the authority of Veraguth vs. Isabela Sugar Co. (57 Phil.

266). In this connection, it should be noted that this Court is vested with original

Security and Acceptance Corporation, alleging that the latter was engaging in

banking operations without the authority required therefor by the General Banking

Act (Republic Act No. 337). Pursuant to a search warrant issued by MTC Manila,

members of Central Bank intelligence division and Manila police seized

documents and records relative to the business operations of the corporation. After

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

examination of the same, the intelligence division of the Central Bank submitted a

deposit of P1,689,136.74, which has been lent out to such persons as the

memorandum to the then Acting Deputy Governor of Central Bank finding that

corporation deemed suitable therefore. It is clear that these transactions partake of

the corporation is engaged in banking operations. It was found that Security and

the nature of banking, as the term is used in Section 2 of the General Banking Act.

Acceptance Corporation established 74 branches in principal cities and towns

Hence, defendant corporation has violated the law by engaging in banking without

throughout the Philippines; that through a systematic and vigorous campaign

securing the administrative authority required in Republic Act No. 337.

undertaken by the corporation, the same had managed to induce the public to open

59,463 savings deposit accounts with an aggregate deposit of P1,689,136.74;

That the illegal transactions thus undertaken by defendant corporation warrant its

Accordingly, the Solicitor General commenced this quo warranto proceedings for

dissolution is apparent from the fact that the foregoing misuser of the corporate

the dissolution of the corporation, with a prayer that, meanwhile, a writ of

funds and franchise affects the essence of its business, that it is willful and has

preliminary injunction be issued ex parte, enjoining the corporation and its

been repeated 59,463 times, and that its continuance inflicts injury upon the

branches, as well as its officers and agents, from performing the banking

public, owing to the number of persons affected thereby.

operations complained of, and that a receiver be appointed pendente lite.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

Superintendent of Banks of the Central Bank was then appointed by the Supreme

Court as receiver pendente lite of defendant corporation.

EN BANC

In their defense, Security and Acceptance Corporation averred that the the

corporation had filed with the Superintendent of Banks an application for

conversion into a Security Savings and Mortgage Bank, with defendants Zapa,

Balatbat, Tanjutco (Pablo and Vito, Jr.), Soriano, Beltran and Sebastian as

proposed directors.

Issue:

Whether or not defendant corporation was engaged in banking

G.R. No. L-20119

June 30, 1967

CENTRAL BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES, petitioner,

vs.

THE HONORABLE JUDGE JESUS P. MORFE and FIRST MUTUAL

SAVING AND LOAN ORGANIZATION, INC., respondents.

Natalio M. Balboa, F. E. Evangelista and Mariano Abaya for petitioner.

Halili, Bolinao, Bolinao and Associates for respondents.

CONCEPCION, C.J.:

operations.

Held.

An investment company which loans out the money of its customers,

collects the interest and charges a commission to both lender and borrower, is a

bank. It is conceded that a total of 59,463 savings account deposits have been

made by the public with the corporation and its 74 branches, with an aggregate

This is an original action for certiorari, prohibition and injunction, with

preliminary injunction, against an order of the Court of First Instance of Manila,

the dispositive part of which reads:

WHEREFORE, upon the petitioner filing an injunction bond in the

amount of P3,000.00, let a writ of preliminary preventive and/or

mandatory injunction issue, restraining the respondents, their agents or

representatives, from further searching the premises and properties and

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

from taking custody of the various documents and papers of the

petitioner corporation, whether in its main office or in any of its

branches; and ordering the respondent Central Bank and/or its corespondents to return to the petitioner within five (5) days from service

on respondents of the writ of preventive and/or mandatory injunction, all

the books, documents, and papers so far seized from the petitioner

pursuant to the aforesaid search warrant.1wph1.t

Such institutions violate Section. 2 of the General Banking Act, Republic Act No.

337, should they engage in the "lending of funds obtained from the public through

the receipts of deposits or the sale of bonds, securities or obligations of any kind"

without authority from the Monetary Board. Their activities and operations are not

supervised by the Superintendent of Banks and persons dealing with such

institutions do so at their risk.

CENTRAL BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES

Upon the filing of the petition herein and of the requisite bond, we issued, on

August 14, 1962, a writ of preliminary injunction restraining and prohibiting

respondents herein from enforcing the order above quoted.

The main respondent in this case, the First Mutual Savings and Loan

Organization, Inc. hereinafter referred to as the Organization is a registered

non-stock corporation, the main purpose of which, according to its Articles of

Incorporation, dated February 14, 1961, is "to encourage . . . and implement

savings and thrift among its members, and to extend financial assistance in the

form of loans," to them. The Organization has three (3) classes of

"members,"1 namely: (a) founder members who originally joined the

organization and have signed the pre-incorporation papers with the

exclusive right to vote and be voted for ; (b) participating members

with "no right to vote or be voted for" to which category all other members

belong; except (c) honorary members, so made by the board of trustees, "at the

exclusive discretion" thereof due to "assistance, honor, prestige or help

extended in the propagation" of the objectives of the Organization without any

pecuniary expenses on the part of said honorary members.

On February 14, 1962, the legal department of the Central Bank of the Philippines

hereinafter referred to as the Bank rendered an opinion to the effect that the

Organization and others of similar nature are banking institutions, falling within

the purview of the Central Bank Act.2 Hence, on April 1 and 3, 1963, the Bank

caused to be published in the newspapers the following:

ANNOUNCEMENT

To correct any wrong impression which recent newspaper reports on "savings and

loan associations" may have created in the minds of the public and other

interested parties, as well as to answer numerous inquiries from the public, the

Central Bank of the Philippines wishes to announce that all "savings and loan

associations" now in operation and other organizations using different corporate

names, but engaged in operations similar in nature to said "associations" HAVE

NEVER BEEN AUTHORIZED BY THE MONETARY BOARD OF THE

CENTRAL BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES TO ACCEPT DEPOSIT OF FUNDS

FROM THE PUBLIC NOR TO ENGAGE IN THE BANKING BUSINESS NOR

TO PERFORM ANY BANKING ACTIVITY OR FUNCTION IN THE

PHILIPPINES.

Moreover, on April 23, 1962, the Governor of the Bank directed the coordination

of "the investigation and gathering of evidence on the activities of the savings and

loan associations which are operating contrary to law." Soon thereafter, or on May

18, 1962, a member of the intelligence division of the Bank filed with the

Municipal Court of Manila a verified application for a search warrant against the

Organization, alleging that "after close observation and personal investigation, the

premises at No. 2745 Rizal Avenue, Manila" in which the offices of the

Organization were housed "are being used unlawfully," because said

Organization is illegally engaged in banking activities, "by receiving deposits of

money for deposit, disbursement, safekeeping or otherwise or transacts the

business of a savings and mortgage bank and/or building and loan association . . .

without having first complied with the provisions of Republic Act No. 337" and

that the articles, papers, or effects enumerated in a list attached to said application,

as Annex A thereof.3 are kept in said premises, and "being used or intended to be

used in the commission of a felony, to wit: violation of Sections 2 and 6 of

Republic Act No. 337."4 Said articles, papers or effects are described in the

aforementioned Annex A, as follows:

I. BOOKS OF ORIGINAL ENTRY

(1) General Journal

(2) Columnar Journal or Cash Book

(a) Cash Receipts Journal or Cash Receipt Book

(b) Cash Disbursements Journal or Cash Disbursement Book

II. BOOKS OF FINAL ENTRY

(1) General Ledger

(2) Individual Deposits and Loans Ledgers

(3) Other Subsidiary Ledgers

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

III. OTHER ACCOUNTING RECORDS

(2) By-Laws

(1) Application for Membership

(3) Prospectus, Brochures Etc.

(2) Signature Card

(4) And other documents and articles which are being used or intended to

be used in unauthorized banking activities and operations contrary to

law.

(3) Deposit Slip

(4) Passbook Slip

(5) Withdrawal Slip

(6) Tellers Daily Deposit Report

(7) Application for Loan Credit Statement

Upon the filing of said application, on May 18, 1962, Hon. Roman Cancino, as

Judge of the said municipal court, issued the warrant above referred

to,5 commanding the search of the aforesaid premises at No. 2745 Rizal Avenue,

Manila, and the seizure of the foregoing articles, there being "good and sufficient

reasons to believe" upon examination, under oath, of a detective of the Manila

Police Department and said intelligence officer of the Bank that the

Organization has under its control, in the address given, the aforementioned

articles, which are the subject of the offense adverted to above or intended to be

used as means for the commission of said off offense.

(8) Credit Report

(9) Solicitor's Report

(10) Promissory Note

(11) I n d o r s e m e n t

(12) Co-makers' Statements

(13) Chattel Mortgage Contracts

Forthwith, or on the same date, the Organization commenced Civil Case No.

50409 of the Court of First Instance of Manila, an original action for "certiorari,

prohibition, with writ of preliminary injunction and/or writ of preliminary

mandatory injunction," against said municipal court, the Sheriff of Manila, the

Manila Police Department, and the Bank, to annul the aforementioned search

warrant, upon the ground that, in issuing the same, the municipal court had acted

"with grave abuse of discretion, without jurisdiction and/or in excess of

jurisdiction" because: (a) "said search warrant is a roving commission general in

its terms . . .;" (b) "the use of the word 'and others' in the search warrant . . .

permits the unreasonable search and seizure of documents which have no relation

whatsoever to any specific criminal act . . .;" and (c) "no court in the Philippines

has any jurisdiction to try a criminal case against a corporation . . ."

(14) Real Estate Mortgage Contracts

(15) Trial Balance

(16) Minutes Book Board of Directors

IV. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

(1) Income and Expenses Statements

The Organization, likewise, prayed that, pending hearing of the case on the merits,

a writ of preliminary injunction be issued ex parte restraining the aforementioned

search and seizure, or, in the alternative, if the acts complained of have been

partially performed, that a writ of preliminary mandatory injunction be forthwith

issuedex parte, ordering the preservation of the status quo of the parties, as well as

the immediate return to the Organization of the documents and papers so far

seized under, the search warrant in question. After due hearing, on the petition for

said injunction, respondent, Hon. Jesus P. Morfe, Judge, who presided over the

branch of the Court of First Instance of Manila to which said Case No. 50409 had

been assigned, issued, on July 2, 1962, the order complained of.

(2) Balance Sheet or Statement of Assets and Liabilities

V. OTHERS

(1) Articles of Incorporation

Within the period stated in said order, the Bank moved for a reconsideration

thereof, which was denied on August 7, 1962. Accordingly, the Bank commenced,

in the Supreme Court, the present action, against Judge Morfe and the

Organization, alleging that respondent Judge had acted with grave abuse of

discretion and in excess of his jurisdiction in issuing the order in question.

BANKING FULL CASES JULY 7, 2015

At the outset, it should be noted that the action taken by the Bank, in causing the

aforementioned search to be made and the articles above listed to be seized, was