Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Anal Sfingter Injuries

Hochgeladen von

widodomeiliaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Anal Sfingter Injuries

Hochgeladen von

widodomeiliaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

General obstetrics

DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03150.x

www.bjog.org

Risk of recurrence and subsequent delivery after

obstetric anal sphincter injuries

E Baghestan,a,b,c LM Irgens,c,d PE Brdahl,a,b S Rasmussena,b,c

a

Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway b Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Haukeland University

Hospital, Bergen, Norway c Medical Birth Registry of Norway, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway d Locus for Registry

Based Epidemiology, Department of Public Health and Primary Health Care, University of Bergen, Norway

Correspondence: Dr E Baghestan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Haukeland University Hospital, N-5021, Bergen, Norway.

Email elham.baghestan@kk.uib.no

Accepted 11 August 2011. Published Online 10 October 2011.

Objective To investigate the recurrence risk, the likelihood of

having further deliveries and mode of delivery after third to

fourth degree obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS).

Design Population-based cohort study.

Setting The Medical Birth Registry of Norway.

Population A cohort of 828 864 mothers with singleton, vertex-

presenting infants, weighing 500 g or more, during the period

19672004.

Methods Comparison of women with and without a history of

OASIS with respect to the occurrence of OASIS, subsequent

delivery rate and planned caesarean rate.

Main outcome measures OASIS in second and third deliveries,

forceps deliveries, birthweights of 3500 g or more and large

maternity units were associated with a recurrence of OASIS.

Instrumental delivery did not further increase the excess

recurrence risk associated with high birthweight. A man who

fathered a child whose delivery was complicated by OASIS was

more likely to father another child whose delivery was

complicated by OASIS in another woman who gave birth in the

same maternity unit (adjusted OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.23.7; 5.6%).

However, if the deliveries took place in different maternity units,

the recurrence risk was not significantly increased (OR 1.3; 95%

CI 0.82.1; 4.4%). The subsequent delivery rate was not different

in women with and without previous OASIS, whereas women

with a previous OASIS were more often scheduled to caesarean

delivery.

Conclusion Recurrence risks in second and third deliveries were

subsequent delivery rate and mode of delivery.

Results Adjusted odds ratios of the recurrence of OASIS in

women with a history of OASIS in the first, and in both the

first and second deliveries, were 4.2 (95% CI 3.94.5; 5.6%) and

10.6 (95% CI 6.218.1; 9.5%), respectively, relative to women

without a history of OASIS. Instrumental deliveries, in particular

high. A history of OASIS had little or no impact on the rates of

subsequent deliveries. Women with previous OASIS were

delivered more frequently by planned caesarean delivery.

Keywords Caesarean, fertility, recurrence, sphincter injuries,

subsequent delivery.

Please cite this paper as: Baghestan E, Irgens L, Brdahl P, Rasmussen S. Risk of recurrence and subsequent delivery after obstetric anal sphincter injuries.

BJOG 2012;119:6269.

Introduction

Obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) occur in 110%

of vaginal deliveries,13 and can result in complications

such as perineal pain, dyspareunia, as well as urinary and

fecal incontinence.46 Cross-sectional studies have identified

strong risk factors such as primiparity, high birthweight

and instrumental delivery,3,7 whereas longitudinal studies

have reported that OASIS tends to recur in subsequent

births,811 but not consistently.12,13

An assessment of the reproductive history in women

who have sustained OASIS, focusing on recurrence as well

62

as the likelihood of having a subsequent pregnancy, would

be of particular value in counselling women who have had

OASIS.

Hospital-based studies on the recurrence of OASIS may

be affected by selection bias and small sample size. Additionally, the choice of reference group may have caused

some of the inconsistency in reported relative risks of

recurrence.12,13 In a big population-based study, Spydslaug

et al.9 reported a 4.3-fold increased recurrence risk of

OASIS in the second delivery. They also reported an

increasing absolute risk of the recurrence of OASIS according to the birthweight of the offspring (23.3% recurrence

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

Obstetric career after sphincter injuries

rate for a birthweight >5000 g). However, little is known

about other possible risk factors for recurrence, such as

instrumental delivery, interdelivery interval and maternal

age. Furthermore, paternal influence, represented in the

fetus by characteristics such as birthweight,14 has to our

knowledge never been analysed. Additionally, little is

known about the recurrence of OASIS beyond the second

birth.

One may expect that a severe delivery complication such

as OASIS would deter a woman from having a subsequent

pregnancy. Previous studies have focused on the quality of

life after OASIS,5,15,16 but subsequent delivery rate and the

mode of subsequent deliveries has not been properly

addressed.11

The aim of the present study was to assess the recurrence

risk of OASIS in second and third deliveries, and to study

the effect of instrumental delivery, interdelivery interval,

maternal age and size of maternity unit on the recurrence

of OASIS. We also wanted to estimate the proportion of

OASIS cases attributable to a history of OASIS, and to

assess the paternal contribution to the recurrence of OASIS.

Finally, we wanted to assess the likelihood of having a

further delivery and mode of delivery after OASIS.

Methods

In this registry-based cohort study, we used data from the

Medical Birth Registry of Norway, which, based on compulsory notification of all live births and stillbirths in the

country after 16 weeks of gestation, comprises records of

more than 2 000 000 births from 1967 to 2004. A notification form including data on maternal health before and

during pregnancy, interventions and complications during

delivery and health of the newborn is completed by the

midwives and attending physicians. The notification form

remained almost unchanged until 1999, when a revised version was introduced.17

All births of a mother were linked by the national identification number, providing sibship files with the mother as

the unit of analysis. The analysis was based on mothers

with singleton, vertex-presenting infants, weighing 500 g or

more, who had their first delivery after 1967: 828 864

mothers in total. In order to compare subsequent rates of

OASIS after vaginal births with and without OASIS, women

with caesarean in previous deliveries were excluded. Only

current vaginal deliveries were followed with respect to the

recurrence of OASIS. When subsequent delivery rates from

first to second and second to third births were calculated,

mothers with caesarean deliveries in previous births (first

and first or second, respectively) were excluded, because

caesarean delivery may influence further delivery rates.18,19

The main outcome, OASIS, was classified according to

the international classification of diseases and included

third-degree injury (ICD-10: O70.2), involving sphincter

muscle, and fourth-degree injury (ICD-10: O70.3), involving sphincter muscle and rectal mucosa. From 1967 to

1998, OASIS was reported to the Medical Birth Registry as

plain text, whereas from 1999 onwards it was reported by

checking a box in the form. The registration of OASIS in

the Medical Birth Registry of Norway has been validated

with a satisfactory result.20,21

The recurrence rate of OASIS was estimated in the

mothers second and third delivery. The odds ratio (OR) of

recurrence was defined as the odds of OASIS among

women having already had OASIS relative to the odds of

OASIS in those without previous OASIS. Adjusted ORs

were obtained from logistic regression with adjustment for

year of delivery (19671974, 19751982, 19831990, 1991

1998 and 19992004), instrumental delivery (yes or no),

maternal age (<20, 2029, 3034, 3539 and 40 years or

older), birthweight (<3000, 30003499, 35003999, 4000

4499, 45004999 and 5000 g or more) and size of maternity unit (<50, 50499, 500999, 10001999, 20002999

and 3000 deliveries per year or more) in the subsequent

delivery. The associations of recurrence of OASIS in the

subsequent delivery with maternal age, instrumental delivery, birthweight, size of maternity unit and interdelivery

interval (<5, 59 and 10 years or more) were assessed by

logistic regression, restricting these analyses to women with

a history of OASIS. To assess whether the effects of birthweight on OASIS in instrumental and non-instrumental

delivery were significantly different, an interaction term

between birthweight and instrumental delivery was added

to the regression model.

In order to increase sample size in analyses of paternal

contribution to the recurrence of OASIS, 48 392 pairs of

first to second, second to third, third to fourth and fourth

to fifth singleton, vertex-presenting vaginal deliveries, with

birthweights of 500 g or more, with the same father and

different mothers were identified. Among these pairs of

births, 18 579 (from 11 372 fathers) and 29 813 (from

17 986 fathers) took place in the same and different maternity units, respectively. To avoid underestimated standard

errors caused by the nested structure of the data (one or

more pairs of births in the same father), we used multilevel

logistic regression analysis.22

To estimate the proportions of all cases of OASIS in the

second and third delivery attributable to a history of

OASIS, population-attributable risk percentages were estimated as 100 (incidence in the populationincidence in

the non-exposed group)/incidence in the population, on

the assumption of a causal relationship between an initial

and a subsequent OASIS. Exposed third deliveries were

those with either OASIS in the first or second delivery.

The subsequent delivery rate was defined as the percentage of all women who had a delivery (second or third)

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

63

Baghestan et al.

subsequent to the first or second delivery. The proportion

of planned caesareans among all subsequent deliveries was

calculated, irrespective of how the delivery was performed

(planned or emergency caesarean or vaginal delivery). The

classification of caesarean deliveries into emergency and

planned caesareans in the Medical Birth Registry was introduced in 1988. Consequently, analyses of planned caesarean

deliveries were restricted to the period 19882004. In the

calculation of the subsequent total delivery rate after the

first and second delivery, each woman was observed until

the end of the observation period (31 December 2004).

Adjustments were made in a Cox proportional hazards

regression of time from OASIS to a subsequent delivery for

possible confounding factors in the previous delivery:

infant death within 1 year (yes or no); year of delivery

(19671974, 19751982, 19831990, 19911998 and 1999

2004); instrumental delivery (yes or no); maternal age

(<20, 2029, 3034, 3539 and 40 years or older); maternal

marital status (married, cohabiting, unmarried or single,

other, unknown); and maternal level of education (<8, 8

10, 1112, 1317, 18 or more years, unknown). Because the

Medical Birth Registry covers all births in Norway, lost to

follow-up were women who emigrated or died. By logistic

regression adjusted for year of delivery we found no significant differences in emigration (0.31.6%), nor in maternal

death (0.51.7%), between groups of women with OASIS

or not in first and second deliveries. Data on women who

did not have a subsequent delivery were treated as censored

observations, with censored time equal to the last date of

registration (31 December 2004), the date of emigration or

maternal death.

The statistical analyses were carried out in spss (SPSS

Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and mlwin (Centre for Multilevel

Modelling, University of Bristol, UK). The regional committee for medical research ethics approved the study protocol (REK Vest no. 247.09).

Results

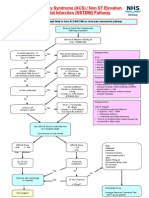

Figure 1 shows the study population according to the

mode of delivery and occurrence of OASIS in first, second

and third deliveries. OASIS occurred in 2.8, 1.1 and 0.7%

of first, second and third vaginal deliveries, respectively.

The data from all 828 864 women, without exclusions, is

included in Figure 1.

Recurrence of OASIS in second and

third deliveries

The occurrence of OASIS in second deliveries subsequent

to deliveries with OASIS was 5.6% (750/13 305) and without OASIS was 0.8% (4546/545 469) [OR 4.2; 95% CI 3.9

4.5; relative to women without a history of OASIS,

adjusted for year of delivery (19671974, 19751982,

64

First delivery

828 864 mothers

Vaginal delivery

755 921 (91.2%)

OASIS

21 692 (2.8%)

Caesarean delivery

72 943 (8.8%)

Second delivery

624 939 (75.0%)

mothers continued to

second delivery

Vaginal delivery

580 155 (92.8%)

OASIS

6503 (1.1%)

Caesarean delivery

44 784 (7.2%)

Third delivery

242 179 (29.2%)

mothers continued to

third delivery

Vaginal delivery

222 690 (92.0%)

OASIS

1506 (0.7%)

Caesarean delivery

19 489 (8.0%)

Figure 1. Study population according to mode of delivery and history

of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) in the first, second and third

delivery.

19831990, 19911998 and 19992004), birthweight

(<3000, 30003499, 35003999, 40004499, 45004499 and

5000 g or more), instrumental delivery (yes or no) and

size of maternity unit (<50, 50499, 500999, 10001999,

20002999 and 3000 deliveries per year or more) in the

second delivery]. Additionally, forceps deliveries, birthweights >3500 g and maternity units with over 3000 deliveries per year were associated with the recurrence of

OASIS in the second delivery (Table 1). Vacuum deliveries

only marginally increased the risk of recurrence (OR 1.5;

95% CI 1.02.3; Table 1). Maternal age of <40 years and

interdelivery interval were not associated with an excess

recurrence risk of OASIS (Table 1). Instrumental delivery

did not increase birthweight-specific recurrence risks

(Table 2). An interaction term between birthweight and

instrumental delivery added to the model was not significant (P = 0.6).

A history of OASIS in the first or second delivery

increased the occurrence in the third delivery (Table 3).

The ORs relative to women without OASIS in the first and

second delivery were highest in women with no OASIS in

the first delivery but with OASIS in the second delivery,

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

Obstetric career after sphincter injuries

Table 1. Risk factors for recurrence of obstetric anal sphincter

injuries (OASIS) in the second vaginal delivery in 13 305 women

with OASIS in the first delivery, Norway, 19672004

Characteristics

Total number

of deliveries

Birthweight (g)

<3000

841

30003499

3167

35003999

5247

40004499

3117

45004999

812

5000 or more

121

Instrumental delivery

Non instrumental

12 921

Vacuum

268

Forceps

116

Maternal age (years)

<20

65

2029

7698

3034

4387

3539

1039

40 or older

116

Interdelivery interval (years)*

<5

11 259

59.9

1818

10 or more

228

Maternity unit (deliveries/year)

<50

46

50499

1172

500999

1376

10001999

3220

20002999

1959

3000 or more

5102

Outside

430

maternity unit

Numbers of

OASIS

N (%)

18

102

252

249

104

25

(2.1)

(3.2)

(4.8)

(8.0)

(12.8)

(20.7)

Adjusted

OR (95% CI)

0.6 (0.41.1)

Reference

1.5 (1.21.9)

2.5 (1.93.1)

4.2 (3.15.6)

7.1 (4.311.6)

702 (5.4)

30 (11.2)

18 (15.5)

Reference

1.5 (1.02.3)

3.2 (1.95.4)

1

383

288

66

12

0.5 (0.13.6)

Reference

1.0 (0.91.2)

1.0 (0.71.3)

1.8 (1.03.4)

(1.5)

(5.0)

(6.6)

(6.4)

(10.3)

623 (5.5)

116 (6.4)

11 (4.8)

Reference

1.1 (0.91.4)

0.7 (0.41.4)

0

46

41

161

113

357

32

0.8 (0.61.2)

0.6 (0.40.9)

Reference

1.2 (0.91.5)

1.4 (1.21.8)

1.1 (0.71.6)

(3.9)

(3.0)

(5.0)

(5.8)

(7.0)

(7.4)

Adjusted for year of delivery (19671974, 19751982, 19831990,

19911998 and 19992004), birthweight (<3000, 30003499,

35003999, 40004499, 45004499 and 5000 g or more), instrumental delivery (yes or no) and size of maternity unit (<50, 50499,

500999, 10001999, 20002999 and 3000 deliveries per year or

more) in the second delivery.

*Adjusted for year of delivery and maternal age in the second delivery.

and women with OASIS in both first and second deliveries

(adjusted ORs 9.3 and 10.6, respectively; 95% CIs 7.311.8

and 6.218.1, respectively).

The population-attributable risk percentage of OASIS in

second and third deliveries as a result of previous OASIS

was 10 and 15%, respectively.

No time trends of ORs of recurrence in second or third

deliveries were found, as assessed by adding an interaction

term between year of the current delivery and a history of

OASIS to the model or stratifying for year of birth (not

presented).

A man who fathered a birth resulting in OASIS was

more likely to father a subsequent birth resulting in OASIS

in another woman who gave birth in the same maternity

unit (adjusted OR 2.1, relative to men with no history of

OASIS, for year of delivery, maternal age and maternal

birth order in the current delivery; 95% CI 1.23.7; 5.6%,

compared with 2.3%). Adjusting for birthweight had a negligible effect. However, if the deliveries took place in different maternity units, the recurrence risk was not

significantly increased (OR 1.3; 95% CI 0.82.1; 4.4% compared with 2.9%).

Subsequent delivery after OASIS

After OASIS in the first delivery, 66.7% of women had a

second delivery compared with 76.9% of women with no

OASIS in the first delivery (Table 4). However, adjusted

hazard ratios revealed no significant differences. Consistently, after stratifying analyses by year of first delivery, no

significant differences were observed in second delivery

rates between women with and without OASIS in the first

delivery (not presented). Cumulative proportions by time

from deliveries with and without OASIS were almost the

same (not presented). Women with OASIS in the first

delivery more frequently had a planned caesarean in the

second delivery than women without OASIS in the first

delivery (6.0 and 1.5%, respectively; Table 4). The difference persisted after adjustment for possible confounding

factors (OR 3.0; 95% CI 2.83.3).

Women with OASIS in the first or second delivery had a

lower subsequent delivery rate (from the second to the

third delivery) than women without a history of OASIS

(Table 5). However, adjusted hazard ratios revealed small

or insignificant differences. Consistently, after stratifying

analyses by year of first delivery, no significant differences

were observed in third delivery rates between women with

and without OASIS in first or second delivery (not presented). Women with a history of OASIS in the first or second delivery were delivered significantly more frequently

by planned caesarean in the third delivery (Table 5).

Cumulative proportions by time from deliveries with and

without OASIS were almost the same (not presented).

In women with OASIS in both first and second deliveries,

the rate of planned caesarean delivery was 13 times higher

than in women with no previous OASIS (adjusted

OR 13.4; 95% CI 9.119.7) (Table 5).

Discussion

Women with a history of OASIS in the first and the twofirst deliveries had four- and ten-fold increased risks of

OASIS in the subsequent delivery, respectively. The recurrence of OASIS was strongly associated with forceps delivery and birthweights of 3500 g or more in the second

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

65

Baghestan et al.

Table 2. Recurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) in the second vaginal delivery by birthweight and instrumental delivery, Norway,

19672004

Instrumental delivery

in the second delivery

Birthweight (g)

in second delivery

No instrumental delivery

<3000

30003499

35003999

40004499

45004999

5000 or more

<3000

30003499

35003999

40004499

45004999

5000 or more

Instrumental delivery Forceps/vacuum

Total numbers of

second deliveries

OASIS in second

delivery

no. (%)

814

3108

5129

2991

761

107

27

59

118

126

51

14

17

96

240

230

96

22

1

6

12

19

8

3

Adjusted

OR

(95% CI)

(2.1)

(3.1)

(4.7)

(7.7)

(12.6)

(20.6)

(3.7)

(10.2)

(10.2)

(15.1)

(15.7)

(21.4)

0.7 (0.41.1)

Reference

1.5 (1.21.9)

2.5 (2.03.2)

4.4 (3.36.0)

7.9 (4.713.3)

1.3 (0.29.8)

3.3 (1.48.1)

3.3 (1.76.2)

5.1 (3.08.7)

5.2 (2.311.5)

8.0 (2.130.0)

Adjusted for year of delivery (19671974, 19751982, 19831990, 19911998 and 19992004), maternal age (<20, 2029, 3034, 3539 and

40 years or older) and size of maternity unit (<50, 50499, 500999, 10001999, 20002999 and 3000 deliveries per year or more) in the second

delivery.

Table 3. Recurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) in third vaginal deliveries, Norway, 19672004

OASIS in first

delivery

OASIS in second

delivery

No OASIS

No OASIS

OASIS

OASIS

No OASIS

OASIS

No OASIS

OASIS

Total number of

third deliveries

207 299

1179

3986

169

OASIS in third

deliveries no. (%)

1106

82

124

16

(0.5)

(7.0)

(3.1)

(9.5)

Adjusted OR

(95% CI)

Reference

9.3 (7.311.8)

4.0 (3.34.9)

10.6 (6.218.1)

Adjusted for year of delivery (19671974, 19751982, 19831990, 19911998 and 19992004), maternal age (<20, 2029, 3034, 3539 and

40 years or older), instrumental delivery (yes or no), birthweight (<3000, 30003499, 35003999, 40004499 and 5000 g or more) and size of

maternity unit (<50, 50499, 500999, 10001999, 20002999 and 3000 deliveries per year or more) in the third delivery.

Table 4. Subsequent pregnancy after first vaginal delivery with or without obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), total and planned caesarean

in second delivery, Norway, 19672004

First delivery

No OASIS

OASIS

Second delivery

Total number of

women with first vaginal

deliveries no. (%)

Total number of second

deliveries no. (%) Adjusted

hazard ratio (95% CI)

Numbers of planned

caesarean in second delivery no. (%)*

Adjusted OR (95% CI)

734 245 (100)

564 826 (76.9)

Reference

14 461 (66.7)

1.02 (1.001.04)

4050 (1.5)

Reference

658 (6.0)

3.0 (2.83.3)

21 676 (100)

Women delivered by caesarean in the first delivery were excluded.

Hazard ratios and odds ratios are adjusted for infant death within 1 year (yes or no), year of delivery (19671974, 19751982, 19831990,

19911998, and 19992004), instrumental delivery (yes or no), maternal age (<20, 2029, 3034, 3539 and 40 years or older), maternal marital

status (married, cohabiting, unmarried or single, other, unknown) and maternal level of education (<8, 810, 1112, 1317, 18 or more years,

unknown) in the first delivery.

*Numbers of second deliveries after 1988 without and with OASIS (denominators) were 271 512 and 11 065, respectively.

66

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

Obstetric career after sphincter injuries

Table 5. Subsequent pregnancy after two vaginal deliveries with or without obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), total and planned caesarean

third deliveries, Norway, 19672004

First delivery

Second delivery

No OASIS

No OASIS

No OASIS

OASIS

OASIS

No OASIS

OASIS

OASIS

Third delivery

Total number of women with

two vaginal deliveries

N (%)

Total numbers of deliveries N (%)

Adjusted hazard ratio

(95% CI)

Numbers of planned

caesarean N (%)*

Adjusted

OR (95% CI)

540 923 (100)

215 823 (39.9)

Reference

1331 (29.3)

0.90 (0.850.95)

4181 (33.3)

1.01 (0.981.04)

213 (28.4)

1.08 (0.941.23)

1552 (1.3)

Reference

92 (8.4)

6.2 (4.97.7)

74 (2.2)

1.7 (1.32.1)

34 (16.9)

13.4 (9.119.7)

4546 (100)

12 555 (100)

750 (100)

Women delivered by caesarean in the first and second delivery were excluded.

Hazard ratios and odds ratios are adjusted for infant death within 1 year (yes or no), year of delivery (19671974, 19751982, 19831990,

19911998 and 19992004), instrumental delivery (yes or no), maternal age (<20, 2029, 3034, 3539 and 40 years or older), maternal marital

status (married, cohabiting, unmarried or single, other, unknown) and maternal level of education (<8, 810, 1112, 1317, 18 or more years,

unknown) in the second delivery.

*Numbers of third deliveries after 1988; denominators in the same order according to OASIS in the first two deliveries were 120 907, 1099, 3348

and 201, respectively.

delivery. However, instrumental delivery did not further

increase the excess recurrence risk observed in heavy newborns. The recurrence risk of OASIS increased with size of

maternity unit, but was not influenced by maternal age

under 40 years or by the interdelivery interval. A man who

fathered a birth that resulted in OASIS was more likely to

father a subsequent birth that resulted in OASIS in another

woman. However, if the deliveries took place in different

maternity units, the recurrence risk was not significantly

increased. The subsequent delivery rate was not different in

women with and without previous OASIS, whereas women

with previous OASIS were more often scheduled for caesarean delivery.

Strengths of our study include the population-based

design and the prospective collection of data, reducing the

risk of selection and recall bias. The national identification

number allowed the linkage of births to both parents. The

long follow-up period allowed us to study recurrence risk

and subsequent delivery rates beyond the second delivery.

Our nationwide registry allowed for the collection of data

in subsequent deliveries, regardless of any change in maternity unit. The OASIS variable has a high validity.20,21 However, increased awareness in the current pregnancy may

have caused a higher sensitivity or case ascertainment in a

delivery after previous OASIS. Furthermore, data on several

possible confounding factors were available.

In this study, women who had OASIS in the first delivery had a roughly four-fold excess risk of OASIS in the

second delivery. Although the risk of the occurrence of

OASIS tends to decrease with vaginal birth order,3 we generally noted an increased recurrence risk in birth order 3.

Women who had OASIS in the second delivery, but not

in the first, were nine times more likely to have OASIS in

the third delivery, and also had high absolute risks (7%).

The risk in women who had OASIS in the two-first deliveries was particularly high (absolute risk 9.5%, adjusted

OR 10.6). Also, women who had OASIS in the first, but

not the second, delivery were at increased risk in the third

delivery, although with a modest absolute risk (3.1%).

This could not result from the exclusion of women with

caesarean delivery in the second delivery, because in a supplementary analysis, inclusion of caesarean delivery had little effect on ORs. The high absolute risk in the third

delivery in women with OASIS in the second delivery was

not expected, and justifies attention to the recurrence of

OASIS beyond the second delivery. It cannot be ruled out

that women with a history of OASIS and subsequent caesarean delivery more often had fourth-degree OASIS and

therefore higher recurrence risks if they were delivered

vaginally.

To our knowledge, nine studies have previously reported

on the recurrence risk of OASIS,813,2325 with conflicting

results. Seven of these studies have reported increased

recurrence risk of OASIS in a second delivery,811,2325 and

another two studies found no increased risk of OASIS in

women with prior OASIS.12,13 The last two studies

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

67

Baghestan et al.

included women with OASIS in birth order 1 in the reference group, and thus probably underestimated the relative

risks arising from the higher risk of OASIS in the first

deliveries, concluding that prior OASIS does not increase

recurrence, and that the increased recurrence found in previous studies could be caused by bias.

Although most women sustaining OASIS in second and

third deliveries did not have previous OASIS, as many as

10% of all cases of OASIS in the second delivery, and 15%

of cases of OASIS in the third delivery, were attributable to

a history of OASIS.

Consistent with another study based on the Medical

Birth Registry of Norway,9 birthweights of 3500 g or more

were strongly associated with a recurrence of OASIS. This

indicates that for women with a history of OASIS and high

estimated fetal weight, caesarean delivery must be considered.9

As in previous studies,12,13 in the present study instrumental deliveries, and particularly forceps deliveries, were

strongly associated with a recurrence risk of OASIS. Vacuum deliveries only marginally increased the recurrence

risk of OASIS. Therefore, vacuum delivery is probably a

better choice than forceps when women with prior OASIS

are delivered instrumentally, unless the clinician is skilled

in forceps delivery.

Although instrumental delivery was strongly associated

with the recurrence of OASIS, it did not further increase

the excess recurrence risk in heavy newborns. This may be

useful information for the clinical decision of whether an

instrumental delivery of a large infant should be performed

in a woman with a history of OASIS.

We have previously reported that maternal age is associated with the occurrence of OASIS.3 However, our results

indicate no association of either maternal age under

40 years or interdelivery interval with the recurrence of

OASIS. Our results provide reassurance that recurrence risk

in older women is not substantially different from that in

younger women, and that the time to the next pregnancy

does not seem to influence recurrence. The recurrence risk

of OASIS was higher in the maternity units with more than

3000 deliveries per year. After adjusting for instrumental

delivery, which is more common in referral hospitals, the

higher risk persisted. However, it cannot be ruled out that

the excess risk was the result of better registration, diagnostic skills or referral of complicated pregnancies to larger

maternity units.

Most risk factors for OASIS relate to the mother, and little is known about a potential paternal influence on OASIS.

A change of female partner after a birth with OASIS should

remove the previous mothers genetic contribution to the

recurrence risk. The excess paternal recurrence rate was not

present if both deliveries took place in different maternity

units, which contradicts a biological paternal effect. How-

68

ever, a man who fathered a birth with OASIS was more

likely to father a subsequent birth with OASIS in another

woman if the delivery took place in the same delivery unit.

Only including births that took place in the same delivery

unit would hold effects such as practices of perineal protection more constant. This potential genetic paternal effect

warrants further study.

Some studies on the quality of life after OASIS have

reported conflicting results,5,15,16 but subsequent fertility

and mode of subsequent deliveries have not been emphasised. Consistent with the present study, one study has

reported a reduced unadjusted likelihood of having a further delivery after OASIS.11 After stratification by year of

first delivery in the present study, no differences from

expected values were generally observed in subsequent

delivery rates (data not shown). A recent small casecontrol study showed that women who had OASIS wished to

postpone or avoid a further delivery, but consistent with

the present study a history of OASIS did not influence

further delivery rates.26 However, the excess rate of

planned caesarean delivery in the present study, which has

been reported to be associated with increased risk of

severe maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality,27

persisted.

Conclusion

The absolute and relative recurrence rates after OASIS in

the first and second deliveries were high. Therefore,

emphasis should be placed on counselling women after an

initial OASIS, and attention should be paid to prevent

OASIS in the first delivery. A history of OASIS had little or

no impact on the subsequent delivery rate. However,

women with previous OASIS more frequently had planned

caesarean delivery. The potential risk factors related to the

father should be further studied.

Disclosure of interests

All authors declare that they have no relevant interests to

declare.

Contribution to authorship

EB contributed by writing the article, performing the statistical analyses, in the conception and design of the study,

and in the interpretation of data. LMI contributed by

supervising, drafting the article and revising it for important intellectual content. PEB contributed by supervising

and drafting the article, and by revising it for important

intellectual content. The main supervisor, SR contributed

by revising the article, by the conception and design of the

study, by the interpretation of data and by supervising the

statistical analyses. All authors approved the final version

of the article.

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

Obstetric career after sphincter injuries

Details of ethics approval

The regional committee for medical research ethics

approved the study protocol (REK Vest no. 247.09).

Funding

The study was funded by the Norwegian Foundation for

Health and Rehabilitation and the Norwegian Womens

Public Health association.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the Norwegian Foundation for

Health and Rehabilitation and the Norwegian Womens

Public Health association for funding the study. j

References

1 Groom KM, Paterson-Brown S. Can we improve on the diagnosis of

third degree tears? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002;101:19

21.

2 Laine K, Gissler M, Pirhonen J. Changing incidence of anal sphincter

tears in four Nordic countries through the last decades. Eur J Obstet

Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;146:715.

3 Baghestan E, Irgens LM, Bordahl PE, Rasmussen S. Trends in risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injuries in norway. Obstet Gynecol

2010;116:2534.

4 Scheer I, Andrews V, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Urinary incontinence

after obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) is there a relationship? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:17983.

5 Samarasekera DN, Bekhit MT, Wright Y, Lowndes RH, Stanley KP,

Preston JP, et al. Long-term anal continence and quality of life following postpartum anal sphincter injury. Colorectal Dis 2008;10:

7939.

6 Haadem K, Ohrlander S, Lingman G. Long-term ailments due to anal

sphincter rupture caused by delivery a hidden problem. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1988;27:2732.

7 Samarasekera DN, Bekhit MT, Preston JP, Speakman CT. Risk factors

for anal sphincter disruption during child birth. Langenbecks Arch

Surg 2009;394:5358.

8 Lowder JL, Burrows LJ, Krohn MA, Weber AM. Risk factors for primary and subsequent anal sphincter lacerations: a comparison of

cohorts by parity and prior mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2007;196:344 e341345.

9 Spydslaug A, Trogstad LI, Skrondal A, Eskild A. Recurrent risk of anal

sphincter laceration among women with vaginal deliveries. Obstet

Gynecol 2005;105:30713.

10 DiPiazza D, Richter HE, Chapman V, Cliver SP, Neely C, Chen CC,

et al. Risk factors for anal sphincter tear in multiparas. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:12337.

11 Elfaghi I, Johansson-Ernste B, Rydhstroem H. Rupture of the sphincter ani: the recurrence rate in second delivery. BJOG 2004;111:

13614.

12 Edwards H, Grotegut C, Harmanli OH, Rapkin D, Dandolu V. Is

severe perineal damage increased in women with prior anal sphincter injury? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2006;19:7237.

13 Dandolu V, Gaughan JP, Chatwani AJ, Harmanli O, Mabine B, Hernandez E Risk of recurrence of anal sphincter lacerations. Obstet

Gynecol 2005;105:8315.

14 Lunde A, Melve KK, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Irgens LM. Genetic

and environmental influences on birth weight, birth length, head

circumference, and gestational age by use of population-based

parent-offspring data. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:73441.

15 Rothbarth J, Bemelman WA, Meijerink WJ, Stiggelbout AM, Zwinderman AH, Buyze-Westerweel ME, et al. What is the impact of

fecal incontinence on quality of life? Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:67

71.

16 Scheer I, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Mode of delivery after previous

obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) a reappraisal? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2009;20:1095101.

17 Irgens LM. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Epidemiological

research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol

Scand 2000;79:4359.

18 Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S, Dalaker K, Irgens LM. Reproductive

career after breech presentation: subsequent pregnancy rates, interpregnancy interval, and recurrence. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:345

50.

19 Tollanes MC, Melve KK, Irgens LM, Skjaerven R. Reduced fertility

after cesarean delivery: a maternal choice. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:

125663.

20 Baghestan E, Bordahl PE, Rasmussen S, Sande AK, Lyslo I, Solvang I

A validation of the diagnosis of obstetric sphincter tears in two Norwegian databases, the Medical Birth Registry and the Patient Administration System. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:2059.

21 Droyvold WB, Rydning A, Baghestan E, Gjessing L, Kristoffersen M,

Norderval S, et al. Validation of the diagnose of anal sphincter tear

in Medical birth registry of Norway and pasient administrative system. SINTEF Helse 2008; Report No., A6301.

22 Goldstein H, Browne W, Rasbash J. Multilevel modelling of medical

data. Stat Med 2002;21:3291315.

23 Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, OConnell PR, OHerlihy C. Anal sphincter

disruption at vaginal delivery: is recurrence predictable? Eur J Obstet

Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;109:14952.

24 Payne TN, Carey JC, Rayburn WF. Prior third- or fourth-degree perineal tears and recurrence risks. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1999;64:557.

25 Peleg D, Kennedy CM, Merrill D, Zlatnik FJ. Risk of repetition of a

severe perineal laceration. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:10214.

26 Wegnelius G, Hammarstrom M. Complete rupture of anal sphincter

in primiparas: long-term effects and subsequent delivery. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:25863.

27 Villar J, Carroli G, Zavaleta N, Donner A, Wojdyla D, Faundes A, et al.

Maternal and neonatal individual risks and benefits associated with

caesarean delivery: multicentre prospective study. BMJ 2007;335:

1025.

2011 The Authors BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2011 RCOG

69

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Pfeiffer SyndromeDokument3 SeitenPfeiffer SyndromeIfanRomliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Atrial Septal DefectDokument2 SeitenAtrial Septal DefecttaheNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Leslie Bullock Resume 4 25 16Dokument3 SeitenLeslie Bullock Resume 4 25 16api-316478659Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Fall Burn Prevention BrochureDokument2 SeitenFall Burn Prevention Brochureapi-320816017Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Parto Prematuro ACOGDokument10 SeitenParto Prematuro ACOGAngela_Maria_M_7864Noch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Healing Rituals of MandayaDokument3 SeitenThe Healing Rituals of MandayaKatrina BuhianNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Nurse ResumeDokument1 SeiteNurse Resumeapi-400113721Noch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- RKU BrochureDokument108 SeitenRKU Brochureh95br100% (1)

- Its Over DebbieDokument1 SeiteIts Over DebbietakischanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- AhmedabadDokument39 SeitenAhmedabadacme financialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Qi 29 6 Dubojska 7Dokument6 SeitenQi 29 6 Dubojska 7DrSumit MisraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Nursing Shift EndorsementDokument6 SeitenNursing Shift Endorsementebrahim102099Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Pedia2 Sepsis (Dr. Seng)Dokument3 SeitenPedia2 Sepsis (Dr. Seng)Tony DawaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Pediatrics Block 2Dokument207 SeitenPediatrics Block 2Ghada ElhassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Anesthesia For The Pet Practitioner, Revised 3rd Edition (VetBooks - Ir)Dokument217 SeitenAnesthesia For The Pet Practitioner, Revised 3rd Edition (VetBooks - Ir)Noviana DewiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Outscraper-2023110313492867fd Doctor +2Dokument234 SeitenOutscraper-2023110313492867fd Doctor +2OFC accountNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07.lymphatic Sysytem 18Dokument24 Seiten07.lymphatic Sysytem 18driraja9999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Focus Fall 2012Dokument8 SeitenFocus Fall 2012fmoore3737Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Acs Nstemi PathwayDokument3 SeitenAcs Nstemi PathwayAliey's SKeplek NgeNersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Central Line Blood DrawDokument20 SeitenCentral Line Blood DrawAnonymous fDSnTnWsfGNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On The Effectiveness of Promotional Strategies With Reference To Hope Hospital".Dokument85 SeitenA Study On The Effectiveness of Promotional Strategies With Reference To Hope Hospital".Satya SriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Pit and Fissure Sealant in Prevention of Dental CariesDokument4 SeitenPit and Fissure Sealant in Prevention of Dental CariesSyuhadaSetiawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV UpdateDokument3 SeitenCV Updateapi-350983586Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hospitals That Offer ObservershipsDokument6 SeitenHospitals That Offer ObservershipsNisarg DaveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spira-Wash GelDokument1 SeiteSpira-Wash Gelapi-251804148Noch keine Bewertungen

- Oral LymphangiomaDokument8 SeitenOral LymphangiomasevattapillaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- All Anatomy Mini QuestionsDokument112 SeitenAll Anatomy Mini QuestionsDiMa Marsh100% (4)

- Opium AlkDokument13 SeitenOpium AlkvaseaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review of Acetaminophen Poisoning - Crit Care - 2012Dokument18 SeitenA Review of Acetaminophen Poisoning - Crit Care - 2012Omar NicolasNoch keine Bewertungen

- SR Phonares II Tooth Mould ChartDokument8 SeitenSR Phonares II Tooth Mould Chartcatalin_adinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)