Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chandra She Karan 2004

Hochgeladen von

Sajid Mohy Ul DinCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chandra She Karan 2004

Hochgeladen von

Sajid Mohy Ul DinCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

The influence of redundant comparison prices and other price presentation

formats on consumers evaluations and purchase intentions

Rajesh Chandrashekaran

College of Business Administration, H-DK2-06, Fairleigh Dickinson University, 1000 River Road, Teaneck, NJ 07666, USA

Abstract

Two studies explore the conditions under which redundant reference price information (ARP) is likely to influence consumers perceptions

of an advertised sale price. Study 1 suggests that an ARP enhances offer-value, but only for consumers who are not involved with the product.

Study 2 incorporates a wider array of price presentation tactics (SP Only, SP +ARP, SP +%Saving and SP +ARP +%Saving) and investigates

a range of responses (transaction value, acquisition value and subsequent purchase intentions). Again, results suggest that ARP only influences

perceived transaction value, and saving information only impacts purchase intentions. Most importantly, these effects are seen only when

involvement is low.

2004 by New York University. Published by Elsevier. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Redundant comparison prices; Consumers evaluations; Purchase intentions

Introduction

Using comparison prices in retail price advertisements

to enhance consumers evaluations is a common tactic.

Chandrashekaran, Monroe, and Viswanathan (2003) conducted a content analysis of over eight hundred sale announcements by six popular retail chains and discovered that

approximately nineteen percent (19%) of the ads presented

a sale price (SP) by itself, an astounding seventy-three percent (73%) provided a comparison using the items regular,

non-sale price and a mere eight percent (8%) presented the

sale price in conjunction with the savings offered without

a comparison price. The authors report that approximately

sixty-six percent (66%) of ads providing a comparison price

advertised it in conjunction with the corresponding sale

price, and thirty-four percent (34%) presented it along with

both the selling price and the implied saving.

Almost two decades of research has consistently shown

that comparison prices influence consumers evaluations

positively (Blair & Landon, 1981; Della Bitta, Monroe,

& McGinnis, 1981; Grewal, Monroe, & Krishnan, 1998;

Mobley, Bearden, & Teel, 1988; Urbany, Bearden, &

Weilbaker, 1988). However, none of these studies has

specifically addressed the role of ARPs when other infor

Tel.: +1-201-692-7245; fax: +1-201-692-7219.

E-mail address: rajeshc@fdu.edu (R. Chandrashekaran).

mation that is easier to process is available. For example,

given a sale price (say $29.99) and information on the saving offered (say $10) one could easily estimate the implied

regular price. This is especially true when the saving is

presented in a dollar-off format. In such cases, the mental

arithmetic may be more easily performed because the sale

price and saving information are structurally aligned, that

is, they are in the same format (dollars). Buyers who are

interested in doing so may estimate the regular price via

simple addition ($29.99 + $10.00 = $39.99). Furthermore,

the cognitive requirement for such an operation is far less

than that required for estimating the regular price from

percentage-off information, which requires both multiplication and addition/subtraction operations (Bettman, Johnson,

& Payne, 1990; Chase, 1978; Johnson, Payne, & Bettman,

1988; Morwitz, Greenleaf, & Johnson, 1998). Therefore,

from a purely logical standpoint, the extra piece of information (i.e., ARP) provides no new/additional information to

consumers. Yet, a whopping 34% of all ads surveyed contained this redundancy. A key question addressed by this

research is: How are consumers influenced by the provision

of presumably redundant ARP information?

This article presents results from two studies. The first

study investigates whether an advertised reference price

(ARP) enhances consumers evaluations even when its

presence is superfluous. Results show that evaluations of

an advertised offer are indeed significantly higher in the

0022-4359/$ see front matter 2004 by New York University. Published by Elsevier. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2004.01.004

54

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

presence of an ARP, but only when the level of involvement is low. The second study incorporates a wider array

of price presentation tactics and examines how the presence of ARP and Saving information (both separately and

together) influence consumers evaluations and subsequent

purchase intentions. Again, results are consistent in that

involvement plays a moderating role in determining how

ARP and Saving information influence perceptions of value

and subsequent purchase intentions.

Motivation and objectives

The motivation for this study comes from the intriguing observation that comparison prices influence consumers

evaluations (see Grewal et al., 1998) even though they may

not offer consumers any additional information. To confirm that at least some consumers actually perceive such

redundant information to be useful in evaluating an advertised offer, a survey was conducted using 35 graduate business students (not included in the main study). They were

shown a mock ad for a pair of jeans without any price

information, and were asked to indicate their preferences

(rank order) for six different presentation formats: (i) Sale

Price only, (ii) Sale Price + Regular Price, (iii) Sale Price +

Competitors Price, (iv) Sale Price + Saving, (v) Regular

Price+Saving, and (vi) Sale Price+Regular Price+Saving.

It is interesting to note that, despite the obvious redundancy,

forty-one percent (41%) perceived the format containing

SP + Regular Price + Saving to be quite useful (ranked as

#1 or #2) in evaluating advertised deals, second only to the

SP + Regular Price format (ranked as #1 or #2 by 65% of

respondents).

Therefore, the primary objectives of this study are: (i) to

investigate whether, given sale price and dollar-off saving

information, the mere presence of an apparently redundant

comparison price can influence consumers evaluations? (ii)

If so, are some consumer groups more prone to their influence than others? As discussed, prior research has not explicitly examined the effects of ARP when its presence is redundant. Although previous research has demonstrated that

ARPs have a positive influence on consumers evaluations,

there have been no empirical investigations of whether particular sub-groups (market segments) are more prone to the

effects of ARPs than others. This research intends to shed

new light on the process by which consumers react to retail

price advertisements.

Such issues may have implications for public policy as well because increased vulnerability within some

sub-segments of the population creates room for possible

deception (Grewal & Compeau, 1992). Thus far, research

on the public policy implications of the use of comparative

price advertising has analyzed possible deception for the

entire population (Compeau & Grewal, 1998). However,

vulnerability of particular sub-segments of the population

has not been addressed.

Theory and hypotheses

Extant research supports the notion that consumers

evaluate retail prices by comparing them to some internal reference price or IRP (Briesch, Krishnamurthi,

Mazumdar, & Raj, 1997; Mayhew & Winer, 1992; Monroe,

1973; Rajendran & Tellis, 1994; Winer, 1986). Retailers

attempt to influence consumers IRPs and subsequent evaluations by including an ARP in conjunction with a temporarily reduced sale price (SP). The ARP is intended to serve as

an anchor that increases the likelihood that consumers will

evaluate the reduced SP favorably against a higher reference

price. There is evidence to indicate that consumers utilize

ARP information to adjust their own internal standards

(Chandrashekaran & Grewal, 2003; Urbany et al., 1988). In

general, the larger the discount (claimed saving), the better

is the response. In addition, when saving information is to be

provided, retailers must decide whether to display the saving using a dollar-off or a percentage-off format (see Chen

& Monroe, 1998). As discussed earlier, each format places

different demands on consumers cognitive resources.1

The moderating role of involvement

Although prior research has discovered an overall positive influence of the presence of ARPs on consumers

evaluations, it has not investigated whether particular

sub-populations (market segments) are more prone to the

effects of ARPs. Common sense logic would suggest that all

consumers should be able to estimate the regular from the

other two pieces of information. However, there are some

important caveats. Specifically, consumers must consider

price to be a relevant variable that is important enough to

demand the attention and cognitive resources required for

processing it. Furthermore, consumers must be willing, able

and motivated to expend the cognitive resources (albeit a

small amount) needed to estimate the implied regular price.

Consumers willingness to engage in such a process is

likely to be a function of whether the additional information

is central to the task at hand. If the available price information (particularly the additional and seemingly redundant

comparative price information) is not deemed to be relevant, then consumers may not attend to this information.2

Therefore, consumers choice of information processing

strategy is directly related to their motivations and perceived relevance, that is, involvement. This construct has

been defined in the literature as consumers interest in and

1 Study 1 addresses the less demanding dollar-off format, which requires

a simple subtraction task to estimate the regular price, and Study 2

incorporates %-off saving to explore if similar pattern of responses is

obtained.

2 It is important to clarify that, by itself, a comparison price is neither relevant nor irrelevant. Rather, its relevance and the likelihood that

consumers will elaborate on it is determined by the availability of other

information that may be easier to process, for example, dollar-off saving

information. That is the specific focus of this study.

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

perceived importance/relevance of the advertised product

(see Celsi & Olson, 1988; Petty, Cacioppo, & Schumann,

1983; Zaichkowsky, 1985).

Consumers, who are involved are more knowledgeable of

products and prices, and are less susceptible to the influence

of peripheral cues. They are also more likely to base their

evaluations on well-established internal reference prices. For

example, prior research (Biswas & Blair, 1991; Biswas &

Sherrell, 1993) has found that involved consumers are more

confident of their internal reference prices than those who

lack involvement with the product. In addition, Mazumdar

and Monroe (1992, p. 67) point out that consumers who lack

confidence in their own estimates of market prices are likely

to be more susceptible to merchant-supplied reference prices

than buyers who are confident of their price knowledge.

Consequently, it is reasonable to expect that an ARP is likely

to influence evaluations only when involvement is low.

Therefore,

H1. Consumers with low levels of involvement evaluate the

offer more positively in the presence of (redundant) comparative price information.

H2. Consumers with high levels of involvement are unaffected by the presence of such (redundant) comparative price

information, that is, these consumers have the same offer

evaluations regardless of whether or not (redundant) comparative price information is present.

Study 1

The data for this study was obtained from one hundred and

three graduate business students during regular class hours.

The task involved evaluating a retail price advertisement for

a model of Levis jeans that normally retails for about $42.

This product was selected because the student subjects are

likely to be familiar with the product/brand, and are likely

to have adequate personal experience in the category.

Method

First, subjects saw a picture of the product, and they provided information about their internal reference prices and

involvement.

55

Mayhew & Winer, 1992; Rajendran & Tellis, 1994; Thaler,

1985; Winer, 1986), internal reference price was measured

on multiple dimensions. Specifically, it was operationalized

as the mean of (i) perceptions of normal market price, (ii)

price expected on the next purchase occasion, (iii) maximum price willing to pay, and (iv) recall of the price paid

on the last purchase occasion.3

To minimize undue influence of the recently elicited IRP

measures on subsequent tasks, the initial task was followed

by several distractions. Specifically, subjects were assigned

an in-class, non-quantitative exercise for about 20 min. This

was followed by a short lecture and class discussion (unrelated to price advertising) for another 20 min.

Finally, subjects saw a mock sale announcement for a

pair of Levis jeans. The ad was based on an actual sale

announcement for the product, but the sale price and saving

information were modified for the purposes of this study.

Each subject saw one of three levels of sale price ($37.95, or

$29.95, or $20.95). These sale prices were chosen to reflect

total savings of $4, $12 and $21, respectively. All subjects

were provided with sale price and saving information (in

$-off format). However, only one-half the subjects saw the

regular non-sale price ($41.95) of the product, whereas the

other half did not. The advertised regular price of the item

was selected to reflect the average of the prices for the same

product in several nearby stores.

Offer evaluation

Subjects evaluated the offer contained in the sale announcement on four items corresponding to their perceptions

of the perceived attractiveness of the offer. Overall perception of the value contained in the offer was assessed as the

mean of subjects responses on the four scale items. The

items corresponded to: (i) sale price acceptability, (ii) perceived worth, (iii) attractiveness of the deal, and (iv) overall

value for money. On each item, subjects indicated the extent to which they agree/disagree with the statement (e.g.,

If I were buying a pair of jeans, I would find the advertised sale price to be acceptable,and Taking advantage of

an attractive deal like this will make me happy). Similar

scales items have been used in previous research investigating how consumers respond to advertised reference prices

(e.g., see Grewal et al., 1998).

Analysis

Involvement

Subjects overall interest in the product/brand and their

perceived importance/relevance of the product/brand was

operationalized as the arithmetic mean of three scale

items (e.g., I am particularly interested in [the advertised

brand]), each ranging from a minimum of 1 (Strongly

Disagree) to a maximum of 5 (Strongly Agree).

Internal reference price

Consistent with previous research (Bearden, Kaicker,

de Borrero, & Urbany, 1992; Klein & Oglethorpe, 1987;

Factor analysis confirmed that the items for the dependent

variable (perceived value) and the independent variables (internal reference price and involvement), loaded on distinct

factors that explained 75% of the total variance. In addition,

3 Rather than unrealistically force all subjects to provide information on

all the measures, they were asked to provide information on the estimates

that they would normally use when evaluating a sale price for this product.

In cases where subjects failed to provide information on one or more of the

measures, the mean was computed using only the information provided.

56

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

the scale reliabilities were high (coefficient alpha = .76 for

IRP, .85 for involvement and .90 for Perceived Offer Value).

Subsequently, IRP was assessed as the arithmetic mean of its

indicators, high and low involvement groups were formed by

performing a median split on the distribution of involvement

scores defined as the sum of the three scale items (mean =

2.87, median = 3.00, Nlow = 53 and Nhigh = 50), and the

four measures of offer value were averaged to provide an

estimate of perceived offer-value.

The experiment constitutes a 2 (high vs. low involvement) 2 (ARP Absent vs. ARP Present) 3 (Saving

Levels) between subjects design. Based on prior research

demonstrating the role of reference prices in determining

offer value (see Briesch et al., 1997 for a comprehensive review), IRP was included in the analysis as a covariate. The

results of a three-way analysis of variance of the dependent

measure (perceived offer value) are shown in Table 1.

Results

Hypotheses H1 and H2 describe that involvement is likely

to moderate the effect of ARP information on perceived offer

value. Although not explicitly stated, the hypotheses imply

that the moderation will occur at all three levels of SP. The

significant ARP Involvement interaction (p .01) shown

in Table 1 generally supports the arguments made in this

study. Specifically, the presence of redundant ARP information exerts a significantly positive influence on evaluations

only when involvement is low (Mean Perceived Value =

3.43 and 2.92 in the ARP-present and ARP-absent conditions, respectively, t = 2.08, p .05). However, involved

consumers are unaffected by the presence/absence of ARP

information (Mean Perceived Value = 3.45 and 3.44 in the

ARP-present and ARP-absent conditions, respectively). Furthermore, the mean responses across the two involvement

groups are significantly different only in the ARP-absent

condition. However, this difference vanishes when the redundant ARP information is present.

Although the results are consistent with the hypotheses,

they are qualified by the presence of a significant three-way

ARP SP Level Involvement interaction that was not hypothesized (see Table 1). The exact nature of the three-way

interaction is shown graphically in Fig. 1AC. In addition,

Table 2 displays the comparison of mean responses across

ARP conditions (absent vs. present) within each involvement group for each level of SP. These exhibits show a sig-

Table 1

Effect of ARP and sale price on perceived value (Study 1)

Source

Type III sum of squares

df

Mean square

(A) Analysis of variance: tests of between-subjects effects (dependent variable: PERCVALU)

Corrected model

56.04a

13

4.31

Intercept

6.50

1

6.50

Covariate: perceived quality

8.53

1

8.53

Covariate: IRP

5.61

1

5.61

Presence of ARP information

0.37

1

0.37

Sale price level

27.16

2

13.58

Involvement

0.53

1

0.53

ARP Information SP Level

0.12

2

0.06

ARP Information Involvement

3.64

1

3.64

SP Level Involvement

0.08

2

0.04

ARP Information SP Level Involvement

2.87

2

1.43

Error

36.55

87

Total

1210.38

101

92.59

100

Corrected total

Significance

10.26

15.46

20.30

13.35

0.88

32.32

1.26

0.14

8.67

0.09

3.42

.00

.00

.00

.00

.35

.00

.27

.87

.00

.91

.04

Mean response

SD

0.42

Sale price

Involvement

ARP

Cell sizes

(B) Cell means by SP, involvement and ARP

$20.95

Low

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

8

8

7

11

3.63

4.22

4.29

3.98

0.94

0.43

0.62

0.84

1.63

(.13)

.83

(.42)

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

9

8

7

9

3.06

3.34

3.04

3.47

0.48

0.42

0.53

0.88

1.31

(.21)

1.16

(.27)

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

8

11

10

6

2.06

2.91

3.18

2.42

0.78

0.76

1.05

1.20

2.38

(.03)

1.33

(.21)

High

$29.95

Low

High

$37.95

Low

High

R squared = .605 (adjusted R squared = .546).

|t-value| (p)

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

(A)

5.0

4.5

Perceived Value

4.0

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

Involvement

1.5

Low

1.0

ARP Absent

(B)

High

ARP Present

Discussion

Perceived Value

4.0

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

Involvement

1.5

Low

1.0

ARP Absent

High

ARP Present

5.0

4.5

4.0

Perceived Value

nificant difference across ARP conditions only in the low

involvement group and in the high SP condition (t = 2.38,

p .05). All other differences are not significant. In light

of this key finding, we must conclude that H1 is supported

only in the high price condition. However, H2 is supported

at all price levels.

Consistent with a wide body of research, this study also

finds that IRP plays a significant role (p .01) in determining offer value. In contrast to prior research findings that

report a main effect for the mere presence of comparison

prices (see review by Compeau & Grewal, 1998) no such effect was obtained here.4 Finally, and as common sense logic

might suggest, a significant main effect of saving level was

found such that higher saving (i.e., lower sale price) yielded

better evaluations. This effect was found regardless of level

of involvement (as substantiated by the non-significant

Involvement SP Level interaction seen in Table 1).

5.0

4.5

(C)

57

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

Involvement

1.5

Low

1.0

ARP Absent

High

ARP Present

Fig. 1. Effects of sale price, ARP information and involvement on evaluation (Study 1). Sale price: (A) $20.95; (B) $29.95; (C) $37.95.

Study 1 addressed the specific case where ARP information is redundant, i.e., when SP and saving information are

readily available. The results support the conjecture that such

contextual cues as ARPs influence evaluations only under

low involvement conditions and with a relatively high SP.

A key question that was raised at the outset is whether retailers can follow an undifferentiated communications strategy and provide redundant information for all consumers, or

whether they need to adopt a segmented strategy. The results

obtained here indicate that the redundancy enhances evaluations significantly among low involved consumers without

actually lowering evaluations among those who are involved

with the product. Therefore, it appears that the optimal approach would be for retailers to implement an undifferentiated strategy and offer redundancy for all.

Interestingly, the content analysis revealed that almost

10% of the retail price advertisements surveyed presented

price information using a SP + Saving format. The results

obtained here indicate that such a tactic is not likely to yield

overall optimum results because individuals with low levels

of involvement are unable to process the saving information provided. One implication of the findings is that retailers may be able to deceive consumers who have low levels

of involvement by simply including a (redundant) ARP, in

conjunction with a high sale price and saving information.5

4 One reason for the different results may be the context in which

ARP effects are examined. It appears that prior researchers were mainly

concerned with investigating the effects of the presence/absence of ARP

by comparing a SP Only condition with a SP + ARP format. However,

one key difference is that this study investigates the role of ARP when

its presence is redundant. Specifically, it compares SP + Saving and

SP + Saving + ARP formats.

5 Given the relatively small cell sizes, one must exercise caution when

interpreting the results and drawing conclusions. Nevertheless, this result

is new and may contain implications for practice and public policy.

Therefore, this issue is one of the objectives of Study 2.

58

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

Table 2

Pattern of factor loadings (Study 2)

Involvement

Perceived quality

Internal reference price (IRP)

.85

.89

.91

.11

.21

.33

.22

.07

.13

.29

.25

.15

.79

.84

.77

.09

.06

.10

.04

.10

.10

.08

.02

.02

.77

.90

.77

Purchase intention

Transition value

.77

.80

.77

.05

.07

.05

.34

.22

.09

.23

.09

.89

.85

.00

.20

.23

measuresa

(A) Independent

Perceived relevance

Level of interest

Overall involvement

Levis are durable

Levis are of good quality

Levis are comfortable

Maximum price

Normal/average price

Lowest price

Offer evaluation

Acquisition value

measuresb

(B) Dependent

Low likelihood of buying (reverse coded)

Intend to take advantage of this sale

High probability that I will buy the advertised product

Advertised deal is attractive

Finding a good deal like this makes me happy

I am getting a lot more than I will be giving up

Good quality jeans for reasonable price

Good value for money

.11

.00

.29

.08

.20

.83

.75

.79

a %Variance: involvement = 28.7; perceived quality = 23.4; IRP = 22.5. Scale properties (coefficient alpha): involvement = .91; perceived quality =

.78; IRP = .72.

b %Variance: AV = 25.10, TV = 25.04, PI = 20.86. Scale properties: AV (coefficient alpha) = .76; TV (bivariate correlation) = .59, p < .01; and PI

(coefficient alpha) = .70.

Study 2

Motivation and objectives

Study 2 was designed to addressed some of the limitations of Study 1 and to gain a more complete understanding

of consumers utilize and respond to additional price-related

information. Specifically, the second study further explores

the ARP Involvement interaction obtained in the high SP

condition. It also includes two additional price presentation tactics (SP Only and SP + ARP) that were revealed by

the content analysis. Such a study is likely to offer a more

comprehensive understanding of how different ARP and

Saving (both separately and together) influence consumers

evaluations.6

Another difference between the two studies is in the way

the saving information is presented. Study 1 assumed that

$-off information should be easier to process than relative

(%-off) information. However, there is evidence that consumers utilize $-off information and/or ARP to estimate

the relative saving (see Chen & Monroe, 1998; Grewal &

Marmorstein, 1994; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979, 1984).

Most recently, Chatterjee, Heath, Milberg, and France

(2000, p. 67) discovered that, when faced with price changes

presented in percentage terms, consumers do not convert

6 Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for steering the research in this

direction.

back to dollars. Therefore, Study 2 investigates whether

similar results will be obtained when relative (rather than

absolute) saving is provided. This tactic is also consistent

with how retailers advertise savings for low-to-moderately

priced products.

A major limitation of Study 1 is that it assessed the impact of a seemingly redundant ARP on a single dimension

of evaluation. Previous research has identified distinct components of value, for example, acquisition value (AV) and

transaction value (TV) that precede consumers intentions

to purchase an advertised product/brand (Grewal, Monroe,

& Krishnan, 1998; Thaler, 1985). However, Study 1 did not

study the effects of ARP on TV and AV separately because it

was not possible to separate out the dimensions of perceived

value (TV and AV). Combining measures corresponding to

theoretically different constructs is likely to have masked

certain patterns in consumers responses. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the influence of alternative presentation

format on each of these constructs separately. In addition,

Study 1 did not measure purchase intentions. Therefore, it

was not possible to examine the role of ARP in different

stages of the evaluation process. To facilitate such investigation, Study 2 incorporates a broader conceptual framework

and assesses each construct (TV, AV, and PI) using multiple measures. Specifically, this study adopts the conceptual

framework validated by Grewal et al. (1998).

Finally, in response to the suggestions of one reviewer, the

measures of involvement included in Study 1 were modified

to better represent the definition of the construct, that is,

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

overall interest and personal relevance of the product/brand.

As in Study 1, involvement was assessed using a three-item

scale.

Conceptual framework

The sections below define the key constructs of the conceptual model and describe the relationship between the constructs (for further details, see Grewal et al., 1998).

Transaction value

This is akin to an affective response that represents the

happiness/elation that consumers feel when they find a good

deal, and has operationalized as consumers perceptions of

how attractive the advertised deal is relative to some internal

standard (IRP). Determinants of TV include IRP and other

contextual factors (e.g., presence of an ARP).

Acquisition value

This construct refers to consumers assessments of the

perceived value of the benefits acquired relative to the perceived price. Perceptions of AV are influenced by the perceived quality (PQ) of the advertised item, and by TV. Furthermore, IRP and other contextual information (ARP and

Saving information) influence AV only indirectly via TV.

Purchase intentions

Willingness to purchase the advertised product is directly

related to perceptions of overall value (AV). However, TV

influences PI only indirectly via AV.

Hypotheses

Previous research (see Compeau, Grewal, &

Chandrashekaran, 2002; Grewal et al., 1998) has investigated advertisers attempts to influence TV by (i) lowering

SP and/or (ii) communicating the increased saving to consumers by providing a comparison price (ARP). This study

extends prior research by including several price presentation formats (SP Only, SP + ARP, SP + Saving and

SP + ARP + Saving). Such investigation will shed light on

how the two pieces of information (ARP and Saving) both

separately and together influence TV, AV and PI.

Role of ARP information

An ARP is intended to serve as an external anchor (reference point) for consumers, especially for those who may

not be confident of their knowledge of market prices. By

definition, this is likely to be true for consumers with low

levels of involvement. The assumption is that consumers

will assimilate at least a portion of the ARP into their existing IRPs (if one is easily accessible). If consumers do not

have rigid IRPs, or one is not easily accessible, then they

may simply use ARP as a reasonable substitute for IRP. Indeed, previous research (Mobley et al., 1988; Urbany et al.,

1988) has found that ARPs (even when they are exagger-

59

ated or ambiguous) influence IRP positively. Most recently,

Chandrashekaran and Grewal (2003) demonstrated that

involvement moderates the assimilation process. Specifically, the authors demonstrate that greater assimilation

of ARP information (evidenced by a change in IRP) occurs when involvement is low. As discussed earlier, IRP

is one of the key determinants of TV. Therefore, ARP

information is more likely to enhance perceptions of TV

when involvement is low. The results presented earlier

(see Study 1) are also consistent with the above argument.

Therefore:

H3. Consumers with low levels of involvement perceive the

offer to be more attractive (i.e., higher TV) in the presence

of comparative price information.

H4. Consumers with high levels of involvement are unaffected by the presence of comparative price information,

that is, these consumers perceptions of TV are the same regardless of whether or not comparative price information is

present.

The above expectations may also be explained by invoking the evaluability hypothesis, which outlines that individuals prefer joint (separate) evaluation when an attribute

is hard (easy) to evaluate (see Hsee, 1996). More recently,

Hsee and Leclerc (1998) used this theory to explain how

consumers evaluate attributes and sale prices of comparable brands. The same logic may be extended to the case of

comparative price advertising, where SP may be evaluated

separately or jointly, that is, in conjunction with ARP. Here,

the difficulty/ease of processing SP (and ARP) may be related to consumers knowledge of market prices and their

overall confidence in this knowledge. As discussed earlier,

consumers with low levels of involvement are less likely

to possess price knowledge, and, therefore, are likely to

find it hard to evaluate SP and/or ARP in isolation (i.e., in

separate evaluation mode). When the two stimuli are presented jointly (the preferred evaluation mode under low involvement), the perceived discount/saving (i.e., perception

of TV) looms larger than when SP is evaluated in separate mode (see Hsee & Leclerc, 1998, p. 176). In other

words, ARP information is essential to assess TV when involvement is low. Therefore, as an extension of H3, it is

expected that these consumers will perceive the two formats that provide ARP information (i.e., SP + ARP and

SP + ARP + Saving) to be significantly better than the two

formats that do not provide this information (SP Only and

SP + Saving). In sharp contrast, involved consumers, who

are likely to be confident of their own knowledge (IRP), are

less likely to rely on externally provided reference information (i.e., ARP), and are likely to prefer separate evaluation

mode.

Consistent with the conceptualization (see also Grewal

et al., 1998), key determinants of AV are perceived quality

(PQ) and TV, and contextual factors (e.g. ARP) dot not influ-

60

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

ence AV directly. Therefore, the presence/absence of ARP

is not expected to change consumers assessments of AV.

Similarly, ARP is not expected to have any direct influence

on consumers purchase intention (PI).

Role of saving information

When ARP information is absent and the ad contains

Saving information (i.e., SP + Saving format), consumers

must expend additional cognitive effort to estimate the implied ARP, then adjust their IRPs accordingly and finally

form perceptions of TV. By definition, consumers who are

not involved lack the motivation and/or the ability to carry

out the mental arithmetic that is required to estimate the

implied ARP. This is especially true when the saving is

presented in relative terms (as is the case in Study 2) because estimating the implied ARP from %-off information

requires fairly complex mathematical operations (implied

ARP = SP/(1 %Saving)). Prior research (Chatterjee

et al., 2000) suggests that consumers (especially those who

lack the need for cognition) are unlikely to convert relative (%) saving information back to dollars. Therefore,

when presented with this format, consumers with low levels of involvement are not likely to be willing or able to

estimate ARP from saving information. Therefore, the presence/absence of saving information is not likely to have a

significant impact on perceptions of TV and, consequently,

on AV.

However, in the absence of other information (that is

easier to process), it is expected that the presence of Saving information acts as a signal that nudges consumers into

action.7 As discussed earlier, this influence is expected only

when involvement is low. It follows that the influence of

saving information on PI is reduced in the presence of ARP,

which is also easier to process. In such situations (low involvement) consumers simply utilize ARP to estimate TV.

Therefore, the influence of saving information on PI is likely

to be moderated by the presence of ARP information. Following the arguments presented earlier, involved consumers

do not rely on any contextual information to assess the value

of the deal. In summary, it is expected that:

H5a. Consumers with low levels of involvement express a

higher willingness to purchase the advertised product in the

presence of (relative) saving information.

H5b. The above effect is moderated by the presence of ARP

information.

H6. Consumers with high levels of involvement express the

same level of intentions regardless of whether or not the ad

contains saving information.

7 Although not the focus of this study, in general, the extent of influence

is likely to be positively related to the posted saving. However, when

the saving is too large, the influence may be negative because consumers

may doubt the veracity of the claim and/or the quality of the item.

Experiment

Study 2 employed a 2 (Presence/Absence of ARP Information) 2 (Presence/Absence of Saving Information) design. Consistent with current practice (see discussion of content analysis), SP information was always made available.

These manipulations yielded the four conditions for Study

2(i) ARP absent-Saving absent (SP Only condition), (ii)

ARP present-Saving absent (SP+ARP condition), (iii) ARP

absent-Saving present (SP+Saving condition), and (iv) ARP

present-Saving present (SP+ARP+Saving condition). Consistent with the objectives of the second study, the analysis

focuses on how consumers with differing levels of involvement (high vs. low) evaluate an advertised (high) sale price

in the presence/absence of ARP and Savings information.

The procedure employed in Study 2 closely matches that

followed in Study 1. One hundred and sixty graduate students participated in the study. As with Study 1, subjects

were initially shown a picture of the product (without any

price information) and were asked to provide estimates of

IRP. In addition, subjects indicated their perceptions of the

quality of the product and extent of involvement.

Perceived quality

Subjects indicated their perceptions of the quality of

the advertised brand on three scale items (ranging from

1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). These

items corresponded to perceived durability (The advertised product is likely to last for a reasonably long time),

comfort (It is unlikely that the advertised product will fit

me comfortablythis item was reverse coded) and overall

quality (Overall, I think the advertised jeans are of good

quality).

Involvement

This construct was operationalized as the mean of responses on three scale items corresponding to (i) overall interest in the product (I am particularly interested in the advertised product), (ii) perceived personal relevance (Given

my personal interests, this product is not very relevant to

me) and (iii) overall feeling of involvement (Overall, I am

quite involved when I am purchasing a pair of jeans for personal use).8 Each item was measured on a five-point scale

ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree.

After a brief interlude, each subject was exposed to one

of four advertisements for a pair of jeans (the same product/brand used in Study 1). The four versions corresponded

8 In response to reviewers concerns that the involvement construct may

have been under-conceptualized, a posterior analysis of the scales used

in Studies 1 and 2 was conducted (N = 100) to compare them with

the more comprehensive 20-item PII scale developed by Zaichkowsky

(1985). This test confirmed that the involvement scales used here have

high correlations with the Zaichkowskys scale (.76 with Study 1 scale

and .92 with Study 2 scale). Therefore, it appears that the items used

in this research might not have compromised the assessment of subjects

involvement with the product.

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

Acquisition value

This construct was operationalized as the arithmetic mean

of three scale items corresponding to subjects perceptions

of overall offer value (e.g., The advertisement shows a good

quality product at a reasonably price).

Transaction value

This component of offer evaluation was operationalized as

the mean of two scale items to reflect subjects evaluations of

the attractiveness of the deal relative to IRP (e.g., Compared

to the price I would normally expect to pay, the sale price

represents a significant saving).

Purchase intention

Subjects intentions to purchase the advertised item at the

posted (or implied) sale price were assessed as the average

of their responses to three scale items (e.g., There is a good

chance that I will take advantage of the advertised sale).

Analysis and results

After confirming that the dependent and independent

measures load onto distinct factors and yield scales that

are highly reliable (see Table 2A and B),10 three separate

ANOVA procedures were performed to assess the roles of

amount/type of information (presence/absence of ARP and

9 The sale price for Study 2 was adjusted very slightly to bring the

saving close to 10% of the regular price. Note that the implied relative

saving in Study 1 was closer to 9.5% than to 10%. It is unlikely that this

degree of change will unduly influence the results.

10 Although this study used fewer measures to assess each construct (see

scales validated by Grewal et al., 1998), it is encouraging to note that the

results of the factor analysis are consistent with previous research and

support the categorization of the dependent measures into three distinct

components corresponding to AV, TV and PI.

5.0

4.5

Transaction Value (TV)

to SP Only, SP + ARP, SP + Saving and SP + ARP + Saving

formats, which collectively describe all the tactics currently

used by retailers. When present, the comparison price corresponded to the products regular, non-sale price (Regularly $41.95). The sale price was held constant at $37.75.9

This price level was selected because Study 2 intends to explore the interesting interaction obtained in Study 1 in the

high price condition. Recall that this was the only condition

in which there was a significant difference between high

and low involvement consumers. Subjects were instructed

to scrutinize and evaluate the advertisement contained in

their booklets. As described earlier, offer-evaluation was

assessed on three dimensions corresponding to acquisition

value (AV), transaction value (TV) and Purchase Intention

(PI). Items for each of these constructs were adapted from

Grewal et al. (1998) and are described below. Subjects indicated the extent to which they agreed with each statement

on a five point scale ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to

5 = Strongly Agree.

61

4.0

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

Involvement

1.5

Low

High

1.0

Absent

Present

ARP Information

Fig. 2. Effect of ARP on transaction value: the moderating role of involvement (Study 2).

Saving information) and Involvement on TV, AV and PI

(see Table 3AC).

Role of ARP information

A highly significant (p .01) ARP Involvement interaction (see Table 3A) supports the premise that involvement

moderates the impact of ARP on perceptions of TV. Fig.

2 displays the observed interaction graphically. Consistent

with H3, the presence of ARP information enhances evaluations significantly when involvement is low (Mean TV =

4.11 when ARP is present vs. 2.81 when ARP is not provided, t = 6.93, p .01). In contrast, and consistent with

H4, involved consumers are not affected by ARP information (Mean TV = 3.32 when ARP is present vs. 3.51 when

ARP is absent, t = .84, p .41). Furthermore, and consistent with the evaluability hypothesis, when ARP information is not provided, evaluations of TV are significantly

higher among involved consumers (Mean TV = 2.81 when

involvement is low vs. 3.51 when involvement is high, t =

3.52, p .01), whereas the reverse is true when ARP information is available (Mean TV = 4.11 when involvement is

low vs. 3.32 when involvement is high, t = 3.71, p < .01).

Consistent with theory, consumers evaluations of TV are

influenced (albeit only moderately) by IRP.11 In addition,

the presence/absence of ARP information does not influence

consumers perceptions of AV (see Table 3B). Consistent

with the conceptual framework, consumers perceptions of

quality (p .05) and transaction value (p .01) are the

key drivers of AV. Finally, consumers purchase intentions

11 The analysis for TV was repeated using each of the indicators of IRP

as covariates. Significant two-way interactions (ARP Involvement) were

obtained in all three cases, but it was discovered that only one of the IRPs

(i.e., highest price) has a significant impact (p = .01) on TV. Although

the key results of this study, that is, the interactive effects of presentation

format and involvement, remain unaffected, this finding may have some

implications for how IRP ought to be operationalized in future studies.

62

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

Table 3

Univariate analyses of variance (Study 2)

Source

Type III sum of squares

df

(A) Transaction value: tests of between-subjects effects (dependent variable: transaction value)

Corrected model

36.24a

8

Intercept

60.67

1

Covariate: IRP

2.26

1

Saving information

0.09

1

ARP information

11.27

1

Involvement

0.22

1

Saving ARP

0.53

1

Saving Involvement

0.29

1

ARP Involvement

19.26

1

Saving ARP Involvement

0.02

1

Error

98.58

131

Total

1815.00

140

134.82

139

Corrected total

(B) Acquisition value: tests of between-subjects effects (dependent variable: acquisition value)

Corrected model

15.76b

9

Intercept

15.76

1

Transaction value

6.85

1

Perceived quality

2.34

1

Saving information

0.15

1

ARP information

0.32

1

Involvement

0.50

1

Saving ARP

0.38

1

Saving Involvement

0.20

1

ARP Involvement

0.00

1

Saving ARP Involvement

0.03

1

Error

57.95

129

Total

1808.11

139

73.72

138

Corrected total

(C) Purchase intention (dependent variable: transaction value)

Corrected Model

59.44c

Intercept

10.64

Covariate: TV

0.04

Covariate: AV

10.37

Presence of ARP

4.17

Presence of saving

0.11

Involvement

17.77

ARP Saving

3.81

ARP Involvement

0.60

Saving Involvement

8.14

ARP Saving Involvement

8.20

a

b

c

Significance

4.53

60.67

2.26

0.09

11.27

0.22

0.53

0.29

19.26

0.02

6.02

80.62

3.00

0.12

14.98

0.29

0.70

0.39

25.59

0.03

.00

.00

.09

.73

.00

.59

.40

.53

.00

.87

3.90

39.45

15.25

5.21

0.33

0.70

1.11

0.84

0.43

0.01

0.06

.00

.00

.00

.02

.57

.40

.29

.36

.51

.92

.81

9.56

15.41

0.05

15.02

6.04

0.15

25.74

5.52

0.86

11.79

11.88

.00

.00

.82

.00

.02

.70

.00

.02

.35

.00

.00

0.75

1.75

17.72

6.85

2.34

0.15

0.32

0.50

0.38

0.20

0.00

0.03

0.45

9.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

6.60

10.64

0.04

10.37

4.17

0.11

17.77

3.81

0.60

8.14

8.20

0.69

Error

88.38

128.00

Total

1407.89

138.00

147.82

137.00

Corrected total

Mean square

R squared = .269 (adjusted R squared = .224).

R squared = .214 (adjusted R squared = .159).

R squared = .402 (adjusted R squared = .360).

are influenced directly by AV, but TV and ARP do not influence it directly (see Table 3C).12 Overall the hypotheses

are strongly supported, and the results provide additional

12 The significant two- and three-way interactions in Table 3C will be

discussed in the next section.

evidence to support the conceptual framework validated by

Grewal et al. (1998).

Role of saving information

Table 3A and B do not reveal significant main effects of

Saving on TV or AV. In addition, in both cases, Saving

Involvement interactions are not significant. These results

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

63

(A) 5.0

4.5

Purchase Intention

4.0

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

ARP Absent

Saving Information

Absent

Present

ARP Present

(B) 5.0

4.5

Purchase Intention

4.0

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

ARP Absent

Saving Information

Absent

Present

ARP Present

Fig. 3. Effect of ARP, saving information and involvement on purchase intention (Study 2): (A) low involvement; (B) high involvement.

support the conclusion that, regardless of the level of involvement, consumers perceptions of TV and AV are not

influenced by the presence of saving information. However, Table 3C shows several significant two-way interactions that are qualified by the presence of a highly significant

three-way (ARP Saving Involvement) interaction. This

finding is consistent with the arguments set forth to develop

the hypotheses (see H5a, H5b and H6) and suggests that

the influence of Saving information on PI is probably being

moderated by level of involvement and by the presence of

ARP information.

Fig. 3A shows how consumers respond to the presence/absence of Saving information and ARP information when involvement is low. In the absence of ARP

information, purchase intentions are significantly higher

when Saving information is available (Mean PI = 4.35

vs. 2.89 when Saving is present and absent, respectively,

t = 5.03, p .01). However, the influence of Saving information on PI disappears when ARP information

is made available (Mean PI = 2.91 vs. 3.33, t = .15,

p > .40). When involvement is high, best results are obtained when both SP and Saving information are absent,

that is, when SP is evaluated in separate mode (Mean

PI = 2.95 is significantly higher than all other conditions, p .05). However, the purchase intentions elicited

by the other formats are not significantly different from

each other. Collectively, these results are consistent with

H5a, H5b and H6, and support the conclusion that both

involvement and ARP moderate the influence of Saving on

PI.

64

(A)

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

Table 4

Effects of information type and involvement

5.0

4.5

Group statistics

Transaction Value

4.0

SP Only

3.5

TV

3.0

AV

2.5

PI

2.0

Involvement

1.5

Low

1.0

High

SP + ARP

TV

AV

SP

SP

SP

SP

+A

+S

R

S

P+

g

in

av

y

nl

O

+A

PI

g

in

av

(B)

TV

5.0

AV

4.5

PI

4.0

Purchase Intention

SP + Saving

SP + ARP +

Saving

3.5

TV

AV

3.0

PI

2.5

Involvement

Mean

SD

|t-value| (p)

Low

High

Low

High

Low

High

18

27

18

28

18

28

2.67

3.48

3.44

3.51

2.94

2.95

0.89

0.92

0.93

0.88

0.99

0.80

2.94

(.005)

.25

(.81)

.03

(.98)

Low

High

Low

High

Low

High

17

13

17

13

17

13

4.12

3.38

3.92

3.38

3.43

2.33

0.84

1.04

0.45

0.68

0.90

1.01

2.13

(.04)

2.61

(.01)

3.15

(.004)

Low

High

Low

High

Low

High

18

14

18

12

18

14

2.94

3.57

3.56

3.58

3.35

2.33

0.82

0.87

0.65

0.71

0.55

0.80

2.09

(.05)

.11

(.91)

3.45

(.002)

Low

23

4.11

0.77

3.12

High

Low

High

Low

High

12

23

11

23

12

3.25

3.55

3.30

2.91

2.28

0.78

0.62

0.81

0.82

0.98

(.004)

.98

(.33)

2.03

(.05)

Involvement

2.0

1.5

Low

1.0

High

R

+A

SP

ng

ng

vi

Sa

P+

vi

a

+S

SP

y

nl

O

R

+A

SP

SP

Fig. 4. Effect of amount/type of information: (A) transaction value; (B)

purchase intention.

Putting it together

Fig. 4A and B summarize consumers responses (TV and

PI) to the four presentation formats. Consumers with low

levels of involvement perceive highest TV when ARP information is readily available (i.e., in the SP + ARP and

SP+ARP+Saving conditions). The mean responses to these

two formats in the low involvement group (Mean TVlow inv =

4.12 and 4.11 in the SP + ARP and SP + ARP + Saving

conditions, respectively) are significantly higher (p .01)

than the mean responses in the other two conditions (Mean

TVlow inv = 2.67 and 2.94 for SP Only and SP + Saving

formats, respectively). However, evaluations of TV made by

involved consumers are not significantly different across the

formats (p > .10).

The mean purchase intention among consumers with low

levels of involvement (Fig. 4B) is highest in the SP + Saving

condition, and is significantly higher (p .01) than purchase intentions evoked by the other three formats. In sharp

contrast, involved consumers express highest intentions (significantly different than other three formats) when presented

with SP information only. Again, these results are consistent

with expectations.

Finally, Table 4 compares the responses of the two involvement groups to each of the price presentation formats.

These results are consistent with the premise that consumers

with low levels of involvement find it difficult to evaluate the

deal in the absence of ARP information, whereas involved

consumers rely primarily on SP information (and on their

own internal standards).13

Discussion

Study 2 addressed many limitations present in Study 1

and intended to gain a better understanding of how ARP

and Saving information (separately and together) influence

each aspect of evaluation (TV, AV and PI). Results support

the conjecture that retailers price presentation tactics are

influential only in particular market segments, and only in

particular stages of the evaluation process. Theoretical and

13 Although this research did not trace subjects thoughts during the

evaluation process and did not explicitly test whether SP and IRP are

more influential when involvement is high, the results are consistent such

a premise.

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

practical relevance of the results, limitations and directions

for future research are discussed below.

Conclusion

The results reported here offer insights that are both new

and interesting. Study 1 questioned the use of ARP in situations when its presence appears redundant and sought to

investigate whether and under what conditions such redundancy may be justified. Consistent with well-established

theory elucidating the role of involvement in consumer

information processing, this study discovered that only

consumer with low levels of involvement are influenced

positively by redundant comparison prices. On a related

note, this research examined whether retailers need to implement different communication tactics in different market

segments, but this conclusion was not supported. Clearly,

this could be good news for retailers! However, this conclusion may be premature because of several limitations in

Study. Building on the first study, Study 2 investigated a

wider array of presentation formats not addressed in previous research and investigated the roles of ARP and Saving

information in different stages of the evaluation process

(TV, AV and PI). Again, results suggest that involvement

plays a moderating role in determining how consumers are

likely to respond to various price presentation formats.

The findings from Study 2 have crucial implications for

practice. An expanded conceptual framework and the inclusion of an exhaustive set of presentation formats helped

uncover crucial differences in the roles of ARP and Saving information among consumers with differing levels of

involvement. Results underscore the need for retailers to

consider implementing different communications tactics in

the two segments. For involved consumers, retailers may

not be able to enhance evaluations and purchase intentions

by including ARP and/or Saving information. Although

perceptions of TV are generally unaffected by inclusion of

additional/redundant information, these consumers express

significantly lower intentions to purchase the product when

any additional information is provided along with SP. Consistent with the evaluability hypothesis, these consumers prefer to evaluate SP in isolation (SP Only format). Therefore,

for involved consumers, retailers must consider presenting

information in SP Only format.14 In contrast, the presence

of ARP is crucial to communicate enhanced TV when involvement is low. For this purpose, retailers may utilize

either SP + ARP or SP + ARP + Saving formats. However,

if the objective is to encourage purchase, retailers should

consider emphasizing the (relative) saving without providing ARP information. In conjunction, these findings suggest

14 Of course, the success of such a tactic rests heavily on the ability of

the retailer to appropriately profile and distinguish consumers who are involved from those who may have low levels of involvement. Alternatively,

retailers may manipulate situational factors to elicit high/low involvement.

65

that, for consumers with low levels of involvement, retailers

need to include ARP information in store ads, newspaper

inserts (FSIs) and other sale announcements to enhance

perceptions of value and attract consumers into the store.

However, once these consumers are in the store, the signs

posted inside the store should emphasize (relative) saving

in conjunction with SP to encourage consumers to buy the

product. Similarly, store (or manufacturer) coupons should

emphasize saving and not ARP information. The results

obtained here suggest that including ARP inside the store

is likely to hurt evaluations leading to sub-optimal results.

Limitations and future research

This research examined one type of comparison price,

that is, regular price. It is unclear whether similar results

will be obtained with other types of reference prices (e.g.,

competitors prices). In both studies, ARP was held constant.

In addition, each study used a different saving presentation

format. Incorporating multiple levels of SP and ARP along

with different saving presentation formats ($-off and %-off)

will undoubtedly advance our understanding significantly.

Additional research is also needed to investigate whether the

results obtained here can be replicated under different conditions (e.g., differently priced products). Finally, this study

would have benefited from process measures that would have

provided insight into consumers thought processes.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the editors and three anonymous reviewers

for their invaluable insight and suggestions.

References

Bearden, William O., Kaicker, Ajit, de Borrero, Melinda, & Urbany, Joel

E. (1992). Examining alternative operational measures of internal reference price. In John F. Sherry Jr. & Brian Sternthal (Eds.), Advances

in consumer research (Vol. 19, pp. 629636). Provo, UT: Association

for Consumer Research.

Bettman, James R., Johnson, Eric J., & Payne, John W. (1990). A componential analysis of cognitive effort in choice. Organizational Behavior

and Human Decision Processes, 45(1), 111139.

Biswas, Abhijit, & Blair, Edward. (1991). Contextual effects of reference

prices in retail advertisements. Journal of Marketing, 55(July), 112.

Biswas, Abhijit, & Sherrell, Daniel L. (1993). The influence of product

knowledge and brand name on internal price standards and confidence.

Psychology and Marketing, 10(January), 3146.

Blair, Edward A., & Landon, E. Laird, Jr. (1981). The effects of reference

prices in retail advertisements. Journal of Marketing, 45(Spring), 61

69.

Briesch, Richard A., Krishnamurthi, Lakshman, Mazumdar, Tridib, &

Raj, S. P. (1997). A comparative analysis of reference price models.

Journal of Consumer Research, 24(September), 202214.

Celsi, Richard L., & Olson, Jerry C. (1988). The role of involvement

in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(September), 210224.

66

R. Chandrashekaran / Journal of Retailing 80 (2004) 5366

Chandrashekaran, Rajesh, & Grewal, Dhruv. (2003). Assimilation of advertised reference prices: The moderating role of involvement. Journal

of Retailing, 79(1), 5362.

Chandrashekaran, Rajesh, Viswanathan, Madhubalan, & Monroe, Kent B.

(2003). Effects of font size incongruity and order of presentation of

price information on price recall accuracy. Working Paper.

Chase, William G. (1978). Elementary information processes. In W. K.

Estes (Ed.), Handbook of learning and cognitive processes (Vol. 5,

pp. 1920). Human information processing, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Chatterjee, Subimal, Heath, Timothy B., Milberg, Sandra J., & France,

Karen R. (2000). The differential processing of price in gains and

losses: The effects of frame and need for cognition. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13, 6175.

Chen, Shih-Fen S., & Monroe, Kent B. (1998). The effects of framing

price promotion messages on consumers perceptions and purchase

intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74(Fall), 353372.

Compeau, Larry D., Grewal, Dhruv, & Chandrashekaran, Rajesh. (2002).

The effects of advertised reference prices and sale prices on perceptions

of value: The role of believability. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 36(2,

Winter), 284298.

Compeau, Larry D., & Grewal, Dhruv. (1998). Comparative price advertising: An integrative review. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing,

17(2), 257273.

Della Bitta, Albert J., Monroe, Kent B., & McGinnis, John M. (1981).

Consumer perceptions of comparative price advertisements. Journal

of Marketing Research, 18(November), 416427.

Grewal, Dhruv, & Compeau, Larry D. (1992). Comparative price advertising: Informative or deceptive? Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 11, 5262.

Grewal, Dhruv, & Marmorstein, Howard. (1994). Market price variation,

perceived price variation and consumers price search decisions for durable goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(December), 452460.

Grewal, Dhruv, Monroe, Kent B., & Krishnan, R. (1998). The effects

of price-comparison advertising on buyers perceptions of acquisition

value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions. Journal of Marketing, 62, 4659.

Hsee, Christopher K. (1996). The evaluability hypothesis: An explanation

of preference reversals between joint and separate evaluations of alternatives. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,

67(September), 247257.

Hsee, Christopher K., & Leclerc, France. (1998). Will products look more

attractive when presented separately or together? Journal of Consumer

Research, 25(September), 175186.

Johnson, Eric J., Payne, John W., & Bettman, James R. (1988). Information

displays and preference reversals. Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Process, 42(1), 121.

Kahneman, Daniel, & Tversky, Amos. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision making under risk. Econometrica, 47(March), 263

291.

Kahneman, Daniel, & Tversky, Amos. (1984). Choices, values and frames.

American Psychologist, 39, 341350.

Klein, Noreen M., & Oglethorpe, Janet E. (1987). Cognitive reference points in consumer decision making. In Melanie Wallendorf

& Paul Anderson (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 14,

pp. 183187). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Mayhew, Glenn E., & Winer, Russell S. (1992). An empirical analysis of

internal and external reference prices using scanner data. Journal of

Consumer Research, 19(June), 6270.

Mazumdar, Tridib, & Monroe, Kent B. (1992). Effects of inter-store and

in-store price comparison on price recall accuracy and confidence.

Journal of Retailing, 68(Spring), 6689.

Mobley, Mary F., Bearden, William O., & Teel, Jesse E. (1988). An

investigation of individual responses to tensile price claims. Journal

of Consumer Research, 15(September), 273279.

Monroe, Kent B. (1973). Buyers subjective perceptions of price. Journal

of Marketing Research, 10(February), 7080.

Morwitz, Vicki G., Greenleaf, Eric A., & Johnson, Eric J. (1998). Divide

and prosper: Consumers reactions to partitioned prices. Journal of

Marketing Research, 35(November), 453463.

Petty, Richard E., Cacioppo, John T., & Schumann, David. (1983). Central

and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating

role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research, 10(September),

135146.

Rajendran, K. N., & Tellis, Gerard J. (1994). Contextual and temporal

components of reference price. Journal of Marketing, 58(January),

2234.

Thaler, Richard. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4(Summer), 199214.

Urbany, Joel E., Bearden, William O., & Weilbaker, Dan C. (1988).

The effect of plausible and exaggerated reference prices on consumer

perceptions and price search. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(June),

95110.

Winer, Russell S. (1986). A reference price model of brand choice

for frequently purchased products. Journal of Consumer Research,

13(September), 250256.

Zaichkowsky, Judith Lynne. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct.

Journal of Consumer Research, 12(December), 341352.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Linking Anthropology: History ClothingDokument5 SeitenLinking Anthropology: History ClothingSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Reading Part 3Dokument2 SeitenFirst Reading Part 3Anonymous 0PRCsW60% (1)

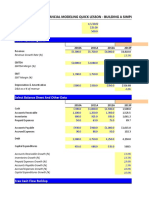

- Wall Street Prep - Financial Modeling Quick Lesson - Building A Simple Discounted Cash Flow ModelDokument6 SeitenWall Street Prep - Financial Modeling Quick Lesson - Building A Simple Discounted Cash Flow ModelSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recent Advances in Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers: An Alcohol-Based Hydrogen EconomyDokument15 SeitenRecent Advances in Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers: An Alcohol-Based Hydrogen EconomySajid Mohy Ul Din100% (1)

- The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility On Firms' Financial Performance in South AfricaDokument23 SeitenThe Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility On Firms' Financial Performance in South AfricaSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Institutional Quality and Initial Public Offering Underpricing: Evidence From Hong KongDokument12 SeitenInstitutional Quality and Initial Public Offering Underpricing: Evidence From Hong KongSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wall Street Prep - Financial Modeling Quick Lesson - Building A Simple Discounted Cash Flow ModelDokument6 SeitenWall Street Prep - Financial Modeling Quick Lesson - Building A Simple Discounted Cash Flow ModelSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insurance Activity and Economic Performance: Fresh Evidence From Asymmetric Panel Causality TestsDokument20 SeitenInsurance Activity and Economic Performance: Fresh Evidence From Asymmetric Panel Causality TestsSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- ChartDokument1 SeiteChartSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation For University Staff Satisfaction: Confirmatory Composite Analysis and Confirmatory Factor AnalysisDokument27 SeitenIntrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation For University Staff Satisfaction: Confirmatory Composite Analysis and Confirmatory Factor AnalysisSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Submission Date: 10-Mar-2021 07:58AM (UTC-0800) Submission ID: 1529370323 File Name: Essay - Docx (29.22K) Word Count: 1371 Character Count: 8583Dokument7 SeitenSubmission Date: 10-Mar-2021 07:58AM (UTC-0800) Submission ID: 1529370323 File Name: Essay - Docx (29.22K) Word Count: 1371 Character Count: 8583Sajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHWMDokument24 SeitenSHWMVineet RathoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surroca PDFDokument28 SeitenSurroca PDFGuillem CasolivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering AspectsDokument10 SeitenColloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering AspectsSajid Mohy Ul DinNoch keine Bewertungen