Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Petru Bejan

Hochgeladen von

Jon2170Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Petru Bejan

Hochgeladen von

Jon2170Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Petru BEJAN1

What is art criticism (any longer)?

Abstract: What is the 'place' of art criticism? Can it be attached to the 'sciences'

considered to be exact? Or, is it rather, more related to the social sciences and humanities? What exactly particularizes and distinguishes a concern such as the one

invoked?2 Are the prejudices that assign a peripheral role, ancillary and even parasitic relative to visual arts justified? Are the prejudices that relate it to aesthetics

and philosophy? Is art criticism an evasive, duplicitous and, thereby, 'suspicious'

activity? Is there an 'ideal' condition of it? What are the competences of the critic?

Can he be substituted by someone else? How should be an eminently critical discourse articulated?

Keywords: art criticism, critics of the critics, critical art

In principle, 'critical' is the endeavour in which someone - the critic,

in this case - formulates judgements regarding the success or failure of a

work, the artistic properties exhibited by it, but also the potential meanings

contained. We can recognize numerous critical registers and typologies; we

speak of descriptive, informative, celebrative (of protocol), interpretative,

evaluative, reflective criticism, of the written and spoken criticism, of the

journalistic criticism and the one with academic destination. Such diversity

requires complementary skills and abilities: historical-artistic, aesthetic, hermeneutical, semiotic, stylistic and, of course, oratorical.

Endangered by trendiness and protocol, art criticism seems to be

perceived today as an infamous, evasive and slippery genre; it evades the

firm, predictable patterns, rarely being assumed as professional destiny or

definitive vocation. Secondary to the current concerns of the protagonists,

plastic criticism is being practiced occasionally, 'among others', depending

on the caprices of the different events that condition it. In retrospect, we

notice that few are the consecrated authors that did nothing but criticism.

Such an occupation is learned 'on the go' or from experience, as long as

there are no schools that would teach you how to practice it perfectly, 'by

the book', or 'recipes' that would insure it a flawless functioning. Hence,

perhaps, the slight cultural 'sub-bidding' compared to the similar applications from other fields. How could be explained the suspicions and precari-

Prof. Dr. Al. I. Cuza University, Iasi, Romania, pbejan@yahoo.com

Cf. Ren Berger, Estetic i comunicare, Editura Meridiane, Bucureti, 1976, pp. 66 sq.

What is art criticism (any longer)?

ousness that evidently accompany the critical discourse in almost all public

hypostases?

Equally esteemed and detested, the criticism specific to visual arts

combines the literary talent and the loquacious performance, the epic abilities of the chronicler with the spontaneous eloquence of the orator. Such

qualities are not always at hand, nor equitably distributed in one and the

same person. It's not always enough to write good, as neither only to speak

beautifully. The critic is asked to give judgement in situations that require

both speculative mobilization and skiving or strategic retreat. A real language equilibristic is put in play, meant to reconcile the celebrative tonalities

dictated by the moment with the severity of the 'judgements' of taste, the

jubilations of the idea with the derisory of the daily fact. Regardless of the

context, the untempered eulogistic pathos is just as ridiculous as the oversized evaluative sobrieties. In one and the same intervention the firmness

and the prudence, the subtle observation and the clich, the speculative

density and the superficiality are met.

The critics of the critics are usually ruthless, punishing harshly any

weakness or hesitation. It is precisely why the space occupied by art criticism is rather one of the inaugural solemnities, of the economistic rhetoric

and of the complicities that don't destroy, but encourage. Statistically speaking, the share of 'demolishing' criticism is derisory compared to the 'positive' or laudatory one. Isn't it that we find just here a sign of the mentioned

precariousness?

Of course, there are more ways of doing criticism. The type familiar

both to the public and the artists seems to be the greeting one, folded on

the immediate expectations of the authors and, often, of the participants in

exhibitions. Present to a significantly reduced extent, the speculative criticism (of ideas), as well as the interpretative one, minimize the references to

authors, highlighting instead the problematic, stylistic or of message intake

of the works exhibited. If it is convincingly articulated, the critical discourse

identifies and discerns significances, proposes analogies, compares the elements, establishes correspondences and filiations, interprets and evaluates

the works brought to the attention. As long as he chooses knowingly, the

critic establishes hierarchies and legitimizes, offering clues regarding the

value of the author of the work. Its authority, taste, flair and erudition, the

weight of arguments, the comprehensive availability, and the oratorical and

literary talent are his best recommendations.

What exactly is generally reproached to the critic? The complaisance, the dishonesty, the moderation, the lack of aggressiveness. As in other cases, the public would prefer treatments more 'sharp', blunt, similar to

the cold and bloody executions from the time of the guillotine. Why is it not

given satisfaction? Why doesn't the critic accept the role of the merciless

headsman? Can he criticize without accusing, that is, without the 'victims'

8

Petru Bejan

being subject to some humiliating public 'deconstructions'? The first role of

the critic is the one of exercising an option. He chooses who to write or

speak about, knowing ab initio that he won't please everyone. Solidarization

is built on a vector of the favourable, yet coherently argued discourse. The

omissions - premeditated or not - are even more painful. Sometimes it is

preferable to be criticized, even harshly, than disregarded.

How do the nowadays critics look like? Raymonde Moulin sketches

the following portrait: 'The critics, who express themselves in the major daily newspapers describe, interpret and evaluate the events of the art scene.

They have in general an academic formation, of art history or philosophy

and practice a primary profession in the secondary or higher education, or

in a school with artistic profile'3. Starting from the '80s, Moulin notices, the

museum conservators have become the competitors of the critics. More recently, the critic is doubled by the curator - the one responsible for designing, organizing and promoting an event.

Almost everywhere, the great critics stood by the talented artists.

People of reflection, they legitimized practices of the most radical types, decisively influencing the receiving of works. The last decades continue the

transition started in the '70s, from art criticism to the 'critical art'. This

means that the critical discourse tends to be ascribed to art, and the profession of the critic increasingly comes closer to the one of the artist. Such

complicity proved to be protean in the USA, where the important critics

(Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, and Joseph Koshut) were formed

right in the artistic environment.

The criticism applied to visual arts has - it's known - a distinct profile. Happening directly, in front of the public and the author, it avoids as

much as possible the falsely-judicious severities and bluntness. The discursive diplomacy of the varnishing usually discourages the accusing pathos or

the eminently hostile atmosphere, familiar to the public executions. The

profile of the critic is different from the one of the police commissioner, invested with the mission of necessarily identifying flaws or crimes, but also

from the one of the inflexible prosecutor, requiring ex officio punishments.

The hermeneutical rule of 'charity' or 'favourable disposition' leads you to

admit that in someone's offer you could find something good, worthy to

notice and promote. The severities - if any - can and must be expressed; not

necessarily abrupt and incriminating, as allusive and ironic. The role of the

critic is no longer to judge and punish vulnerabilities, but to discern, evaluate and understand. Depending on these he exercises the prerogative of option;

he chooses, thus, according to his own tastes, aims and expectations.

The status of art criticism must be sought not in the methodological

frameworks of sciences, regardless of their nature, 'positive' or humanistic,

3

Raymonde Moulin, Lartiste, linstitution et march, Flammarion, Paris, 2009, pp. 206-208

9

What is art criticism (any longer)?

'exact' or speculative. As in philosophy, there is an inherent 'scientificity', of

historical and conceptual nature, around which are strengthened the data of

the specific competence. The critical approach mobilizes both cognitive and

discursive abilities, but is not only limited to these. In such a context, the

library is only a starting point. Outside the gallery, the museum or the specialized publications, i.e. excluding the places where it is effectively practiced, the criticism contradicts itself. More than pure theory or applied rhetoric, it is attitude, commitment, axiologically and culturally centred action.

Perhaps that is why the definitions and explanations satisfy only to a little

extent...

10

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

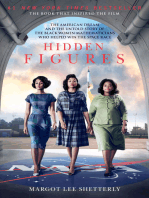

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Why & How To Teach ArtDokument158 SeitenWhy & How To Teach ArtSpringville Museum of Art100% (4)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Visualizing Money PDFDokument22 SeitenVisualizing Money PDFmalditongguy100% (1)

- Nudity A Cultural Anatomy Ruth BarcanDokument321 SeitenNudity A Cultural Anatomy Ruth Barcanbaubo100% (7)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Jean-Baptiste Lamarck - Zoological PhilosophyDokument297 SeitenJean-Baptiste Lamarck - Zoological Philosophyfimpenbet100% (2)

- English For Information Technology Level 2Dokument34 SeitenEnglish For Information Technology Level 2fornanalady44% (9)

- The Cosmopolitan Milieu of Serbian TownsDokument54 SeitenThe Cosmopolitan Milieu of Serbian TownsannboukouNoch keine Bewertungen

- LEE Pamela M. Lee - Chronophobia On Time in The Art of The 1960s - Livro CompletoDokument395 SeitenLEE Pamela M. Lee - Chronophobia On Time in The Art of The 1960s - Livro CompletoCarol IllanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Color Wheel LessonplanDokument5 SeitenColor Wheel Lessonplanapi-299835698100% (1)

- Pioneers of Electronic Art (Ars Electronic A 1992)Dokument221 SeitenPioneers of Electronic Art (Ars Electronic A 1992)Мика Шлиммер100% (7)

- Art of QuestioningDokument2 SeitenArt of QuestioningWalter Evans LasulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDF 3Dokument7 SeitenPDF 3Jon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Artificial Moral AgencyDokument17 SeitenArtificial Moral AgencyJon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Commentary: The Declaration of Helsinki: An Update On Paragraph 30Dokument5 SeitenCommentary: The Declaration of Helsinki: An Update On Paragraph 30Jon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- No Evidence For Feature Overwriting in Visual Working MemoryDokument16 SeitenNo Evidence For Feature Overwriting in Visual Working MemoryJon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Ethical PrinciplesDokument13 SeitenBasic Ethical PrinciplesJon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Proof of Semantics in AmnesiaDokument17 SeitenProof of Semantics in AmnesiaJon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Splicing AlternativoDokument8 SeitenSplicing AlternativoJon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Allen Newell 1927-1992: ArticlesDokument29 SeitenAllen Newell 1927-1992: ArticlesJon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- 5097 Aprendizaje-5HT y PlasticidadDokument6 Seiten5097 Aprendizaje-5HT y PlasticidadJon2170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Neues Museum - Exhibition Guide - Sherrie Levine. After AllDokument48 SeitenNeues Museum - Exhibition Guide - Sherrie Levine. After AllIanina IpohorskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final ReportDokument61 SeitenFinal ReporttoolsinschoolsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creative ChaosDokument7 SeitenCreative ChaosIji OluwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Content Checklist: Desrivtive Title Remarks Subject Code Pre-Requisite Final GradeDokument7 SeitenCurriculum Content Checklist: Desrivtive Title Remarks Subject Code Pre-Requisite Final GradeFranklyn TroncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 5 Applied ArtsDokument51 SeitenChapter 5 Applied ArtsUltra BoostNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3Dokument2 SeitenChapter 3benedictgutierrez0711Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading in Visual Arts Chapter 1Dokument11 SeitenReading in Visual Arts Chapter 1Marife PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studies in Tectonic Culture - The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century ArchitectureDokument29 SeitenStudies in Tectonic Culture - The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century ArchitectureKevin SuryawijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crafts From India, Shilparamam, Crafts Village of Hyderabad, Shilparamam Crafts Village, IndiaDokument2 SeitenCrafts From India, Shilparamam, Crafts Village of Hyderabad, Shilparamam Crafts Village, IndiavandanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts and Design - Apprenticeship and Exploration of The Perfroming Arts Theater - 1 PDFDokument4 SeitenArts and Design - Apprenticeship and Exploration of The Perfroming Arts Theater - 1 PDFBenjie Rodriguez PanlicanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Making A Good Script Great - Revised & ExpandedDokument278 SeitenMaking A Good Script Great - Revised & ExpandedSavan RabariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kanchan Gurung CVDokument2 SeitenKanchan Gurung CVkaigrgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art AriseDokument2 SeitenArt AriseDr.Nirmala BilukaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstracts FinalDokument44 SeitenAbstracts FinalAni HanifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contempom 2Dokument27 SeitenContempom 2Mark Andris GempisawNoch keine Bewertungen

- PaintingsDokument3 SeitenPaintingssolomon sNoch keine Bewertungen

- English EssayDokument32 SeitenEnglish Essayapi-3731661100% (3)

- Eating Banana With FruitsDokument7 SeitenEating Banana With FruitsOmar AdilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fine Art - August 2019Dokument33 SeitenFine Art - August 2019ArtdataNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Simplicity A Comparative Analysis Between Iconography Ang Gregorian Chant, Br. Ivan VirgenDokument24 SeitenThe Art of Simplicity A Comparative Analysis Between Iconography Ang Gregorian Chant, Br. Ivan VirgenIvan Alejandro Virgen ManzanoNoch keine Bewertungen