Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

WFP Uganda and Burkina Faso's Trial To Reduce Post-Harvest Losses For Smallholder Farmers

Hochgeladen von

Jeffrey MarzilliOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

WFP Uganda and Burkina Faso's Trial To Reduce Post-Harvest Losses For Smallholder Farmers

Hochgeladen von

Jeffrey MarzilliCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Regional Bureau for

OMN|Knowledge Series

East and Central Africa

This paper is part of a knowledge sharing series to inform better programming and communicate results.

WFP Uganda and Burkina Fasos Trial to

Reduce Post-Harvest Losses for Smallholder Farmers

Every year across sub-Saharan

Africa unacceptable levels of

food loss continue to occur.

In 2011, the UN Food and

Agriculture Organization (FAO)

reported annual food losses in

the region exceeding 30 percent

of total crop production, valued at more than

USD 4 billion more than all international food aid

provided to African countries annually. Although

losses are found at every stage in the supply chain,

the bulk occur pre-farm gate due to poor

harvesting, drying, processing and storage of crops.

These losses directly contribute to the food

insecurity of millions of smallholder farming families.

As food represents up to 80 percent of household

spending and crop production is the principal source

of family income, there is considerable potential to

improve food security and livelihoods.

WFP conducted an Action Research Trial in Uganda

and Burkina Faso involving governments, NGOs and

private sector partners to address post-harvest food

losses at farm-level. The trial built upon existing

programmes, Purchase for Progress (P4P)

networks and work already done by FAO and IFAD

to improve post-harvest practices. It focused on

400 farmers and applied proven practices from

developed countries, recent learning from successful

trials in other developing regions, and theoretical

recommendations from research.

WFPs trial was highly successful, illustrating that

post-harvest crop losses in developing countries can

be dramatically reduced when appropriate capacity

development and improved farming equipment are

introduced. WFP has recently mounted a special

operation to reach more farmers with the improved

technologies and practices.

Where is it happening?

Two farming districts were selected from both Uganda and Burkina

Faso. Target study sites were located within small villages in Gulu

and Soroti districts in Uganda and the districts of Bobo-Dioulasso

and Ouahigouya in Burkina Faso.

Who is it for?

The trial directly involved 400 low-income smallholder farmers,

of whom nearly 40 percent are female. Two hundred families

benefitted directly in both countries where the trial was conducted.

What is the impact so far?

For all participating farmers, without exception, the new procedures

and technologies enabled food losses to be reduced by more than

98 percent regardless of the crop and regardless of the duration of

storage. The near-eradication of post-harvest food losses at the

farm level is a very significant outcome in itself, and is further

amplified by the additional benefits of augmenting household

finances (as crops could be stored and sold during more favorable

market conditions), improving family well-being (through increased

nutrition and reduced exposure to food contaminations) and

increasing the surplus of quality food available for community

consumption.

The technologies used also reportedly reduced womens workloads

as the time-consuming process of daily cleaning and shelling of

cereals was eliminated.

What was the timeframe?

The research trial was carried out between August 2013 and April

2014. Preparatory stages leading up to the harvest in December

were followed by a three-month period of field support and close

monitoring of the trial results.

All images by Simon Costa/WFP and Neil Palmer.

How WFP Uganda and WFP Burkina Faso did it.

KEY STEPS

2

3

4

5

6

Identified successful post-harvest management (PHM) practices used in other regions.

Instead of piloting completely new PHM practices and technologies, WFP put into effect

proven farming practices from developed countries and well-researched ideas from expert

organizations. The use of proven methods increased the chances of the trials success.

Partnered with governments, NGOs, United Nations and the private sector. Partnerships

provided WFP with knowledge and expertise, existing networks and access to local

communities. The collaboration and buy-in of governments at the central and district levels

aimed to ensure the sustainability of the trials results.

Developed farmer capacity. One-day training workshops increased farmer awareness of

key biological and environmental factors leading to grain rotting and fungal infestation,

qualitative and quantitative losses from insect and weather spoilage, and food safety hazards.

Capacity development focused on preventing these issues during five procedural stages:

harvesting, drying, threshing, solarisation and on-farm storage.

Distributed new farming equipment and provided field support. Detailed demonstrations

regarding the correct handling procedures for the new storage units were provided and all

participating farmers received one or more of the new storage units, as well as equipment

to assist with drying and solarisation of crops, to use on their farms for the upcoming harvest.

Monitored the process closely. Over 30 percent of trained farmers were involved in the

monitoring phase, representing small- and medium-size farming families, all the storage

technologies and major crop varieties, and sub-counties from all selected districts.

Loss measurements were recorded at 30, 60, and 90 days. Samples from storage units

were analysed and the weight of undamaged crops was recorded at the end of the process.

Reported and disseminated results. A comprehensive report, Reducing Food Losses in

Sub-Saharan Africa, was prepared to demonstrate the successes and learning from the project.

The report was circulated globally through numerous channels, including UN agencies, learning

institutes, donor contacts, and food security conferences. It can be found online at :

http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/special_initiatives/WFP265205.pdf

New Technology Farming Equipment used in the Action Research Trials

Super Grain Bags

Zero Fly Bags (<100 kg)

Plastic Silos (100-150 kg)

Metal Silos(540-1200+ kg) GrainSafes (1000+ kg)

(<100 kg)

Excellent Performance

Very Good Performance

Very Good Performance

Excellent Performance

Very Good Performance

Improved Traditional

Granaries (1000+ kg)

Multi-layer polyethylene

storage. Water resistant

and airtight, but no rodent

protection. Placed inside

ordinary storage bags.

Environmental issue of

plastic disposal.

Insecticide-infused

polypropylene bags.

Limit infestation of grain

within the bag (short period

where insects can survive

before contact with inner

lining of bag). Not hermetic,

no rodent protection.

Environmental issue of

plastic disposal.

Plastic PVC storage units.

Simple conversion of locally

produced liquid storage

containers. Highly durable

and, with minor

adjustments, hermetic.

Rodent and pest proof.

Deoxygenation at filling

can be difficult.

Environmental issue

of plastic disposal.

Robust units constructed

from galvanized iron.

Water resistant, hermetic,

rodent and pest proof.

Provide protection against

thieves. Require structural

adjustment to home prior

to storage. Long-term

solution.

Made of food-grade,

UV-resistant flexible PVC.

Designed for both indoor

and outdoor installations.

Provides compact storage

for large volumes. Water

proof and hermetic, but no

rodent protection.

Improvement to traditional

storage. Made of local

material. Inexpensive and

durable. Rodent protection

added, but unable to

resolve post-harvest

problems of pest

infestation, moisture

control and resistance to

the elements. Not hermetic.

Price: USD 2.50USD 3

Life: 2-3 harvests

Price (estimate): USD 3.50

Life: 2-3 harvests

Price: USD 20USD 36

Life: 57 years

Price: USD 200USD 320

Life: 2025 years

Price: USD 180USD 200

Life: TBA

Price: USD TBA

Poor Performance

Side-by-side comparison

of crops after 90+ days

of storage using

traditional and new

storage units.

Left: Red beans

Middle: Black-eyed peas

Right: Maize

How were communities involved?

Participating farmers were selected among registered members of

WFPs Purchase for Progress (P4P) Farmer Organizations, and all

training, mobilization and support under the trial was restricted to

this particular group. However, a subsequent special operation in

Uganda has reached an additional 16,300 beneficiaries.

Who were the main partners and donors?

Within WFP, the trial benefitted greatly from the active support,

existing networks and strong relationships of the P4P project in both

countries. Furthermore, the trial was designed to complement a

three-year interagency project with FAO and IFAD to mainstream

food loss reduction initiatives. Sponsored by the Swiss Agency for

Development and Cooperation, the joint project provides a global

information platform for streamlining best practices in post-harvest

management, to which the lessons learned from the WFP field trials

will directly contribute.

The field monitoring and trial evaluations were carried out by three

independent farmer organizations.

What are the success factors?

Taking advantage of existing research. The well-documented

research conducted in Central America by the Swiss Agency for

Development and Cooperation informed WFPs trial design and

implementation. The PostCosecha programme was developed in

Honduras in the 1980s and scaled up throughout Central America.

It was a successful initiative which greatly advanced post-harvest

management practices of local smallholder farmers and led to very

high adoption rates of new storage technologies and significant

reductions in annual food losses over a period of more than 20 years.

Utilising existing P4P networks. Taking advantage of the established

knowledge and resource infrastructure enabled the trial to move

more quickly and build upon the good work already done in the

chosen districts by WFP P4P, FAO and IFAD to improve post-harvest

systems at the community level. P4P also played a critical role beyond

the research trial by providing the participating smallholder farmers

with increased opportunities to connect with agricultural markets

and receive fair market prices for their surplus product.

Providing all training material to farmers in the local district

languages. Although administratively challenging, translated materials

removed any potential language barriers and expanded the learning

as farmers could share the materials with family members and

villagers not attending.

Following a zero fumigation policy. Phosphine fumigation against

pests was not allowed during the trial, as correctly sealed hermetic

storage units were expected to quickly kill any pests or insects

present at the time of storage through oxygen deprivation. As the

use of fumigants is officially forbidden in some African countries,

the proven success of the storage technologies without fumigants is

significant for the wider dissemination of these technologies on the

continent.

For more information, contact:

Simon Costa

simon.costa@wfp.org

What are the challenges?

How can it be sustained and scaled up?

Selecting and engaging the right partners. The trial required

partnerships at strategic and operational levels. Since the project

spanned multiple regions, the identification of implementing partners

was more challenging. It also meant that the engagement of

government actors at different levels and in many locations had to

be secured and maintained.

The approach adopted is highly scalable as indicated by the strong

performance in the trial as well as the previous track record of the

technologies tested. None of the equipment or procedures in the

trial were new, which means that the expertise required for their

broader implementation exists in the global

farming technology community. The degree to

which the successful technologies and practices

can be disseminated depends largely on the

supporting policies of host governments and

the willingness of collaborating agencies

and the global community to assist with

implementing the solutions.

Selecting and training the participating farmers.

Ensuring that 50 percent of all training

participants were female was a key requirement

of the trial. Once participants had been selected,

the project had to provide context appropriate

training. Specific programmes had to be

developed in local languages to match regional

crops and farming practices. Several trainings-oftrainers had to be organised to equip the people

involved in outreach with both technical

knowledge and presentation skills. The project

also had to grapple with logistical challenges in

organising venues and transporting presentation

and demonstration equipment, training

materials, power generators and facilitators and

even caterers to many remote locations every

week. After the initial trainings, field support

teams had to be organised to provide refresher

training and to ensure that the new storage equipment were being

used correctly by farmers.

Organising the production and distribution of PHM equipment.

As the equipment used in the trial was new to the project context,

local artisans had to be identified and then trained to produce the

equipment meeting high standards for quality and timeliness. Raw

material prices and shipping costs had to be negotiated with

suppliers. Once produced, the equipment had to be distributed to

hundreds of individual farms, which required the identification of

reliable transport providers with fleet capacity to reach remote

farming areas on schedule, despite poor road infrastructure.

Monitoring and replicating results. The broad geographical area

covered by the trial made the collection of detailed monitoring data

more challenging but the continuous reporting of results was

important in order to keep strategic partners updated and engaged

in the project. In order to facilitate the replication of the results in

other contexts, a clear link had to be made between the projects

performance indicators and specific learning outcomes.

The trial successfully overcame all of these challenges, and similar

projects would benefit from anticipating them in their planning.

What are the lessons learned so far?

All of the new technology storage units proved to be highly

effective. The hermetic units performed marginally better than the

treated, non-hermetic storage units; however, compared to the

biological impact recorded within the traditional non-treated,

non-airtight environment, all five of the new options were successful.

The sixth option, the modified traditional granary, failed to provide

measurable improvements against the non-modified units.

What skills are required for success?

The introduction of activities similar to this trial

requires some technical knowledge and skills.

Familiarity with local post-harvest handling

practices, an understanding of food safety

issues and the causes of post-harvest losses,

and practical knowledge of proven post-harvest

management methods are crucial to enable

context-appropriate training of farmers and the

selection of the most suitable technologies.

Skills in communication, building networks and

negotiating agreements are also helpful to

ensure community buy-in, garner resources and support, and

maintain momentum.

How much did it cost?

The approximate costs of the trial were USD 75,000 in Burkina Faso

and USD 80,000 in Uganda.

What are the next steps?

WFP has mounted a special operation to increase the number of

farmers who can benefit from the improved technologies and

farming practices in and beyond the two trial countries. In Uganda,

16,300 new beneficiaries have been trained, and 63,000 storage and

handling units have been distributed. Due to a lack of donor funding,

the scale-up in Burkina Faso has been delayed until later in 2015.

Last Word

Increasing the number of effective household storage units in each

farming district is an important aspect of regional food security and

rural livelihoods since it ensures continuous stable supply of food,

provides better farm incomes and significantly increases quantity

of safely stored grain. The proven, affordable and scalable

post-harvest handling technologies and practices implemented in

this action research trial can make a strong contribution towards the

Zero Hunger Challenge to achieve 100 percent access to adequate

food all year round, sustainable food systems, growth in smallholder

productivity and income, and zero loss of food.

December 2014

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Catalysing Dialogue and Cooperation to Scale up Agroecology: Outcomes of the Fao Regional Seminars on AgroecologyVon EverandCatalysing Dialogue and Cooperation to Scale up Agroecology: Outcomes of the Fao Regional Seminars on AgroecologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Farmer Field School: Guidance Document Planning for Quality ProgrammesVon EverandFarmer Field School: Guidance Document Planning for Quality ProgrammesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Averting Risks to the Food Chain: A Compendium of Proven Emergency Prevention Methods and ToolsVon EverandAverting Risks to the Food Chain: A Compendium of Proven Emergency Prevention Methods and ToolsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disaster Risk Reduction at Farm Level: Multiple Benefits, No Regrets: Results From Cost-Benefit Analyses Conducted in a Multi-Country Study, 2016-2018Von EverandDisaster Risk Reduction at Farm Level: Multiple Benefits, No Regrets: Results From Cost-Benefit Analyses Conducted in a Multi-Country Study, 2016-2018Noch keine Bewertungen

- Farmer Field Schools for Family Poultry Producers: A Practical Manual for FacilitatorsVon EverandFarmer Field Schools for Family Poultry Producers: A Practical Manual for FacilitatorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fruit and Vegetables: Your Dietary Essentials: The International Year of Fruits and Vegetables, 2021, Background PaperVon EverandFruit and Vegetables: Your Dietary Essentials: The International Year of Fruits and Vegetables, 2021, Background PaperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Namibia Studies and Pilot Projects On Urban Agriculture by University of Namibia - OshakatiDokument9 SeitenNamibia Studies and Pilot Projects On Urban Agriculture by University of Namibia - OshakatiFree Rain Garden ManualsNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Year of Plant Health: Final Report: Protecting Plants, Protecting LifeVon EverandInternational Year of Plant Health: Final Report: Protecting Plants, Protecting LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SeedsGROW Progress Report: Harvesting Global Food Security and Justice in The Face of Climate ChangeDokument77 SeitenSeedsGROW Progress Report: Harvesting Global Food Security and Justice in The Face of Climate ChangeOxfamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Rinderpest Action Plan: Post-EradicationVon EverandGlobal Rinderpest Action Plan: Post-EradicationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Submitted To The ILEIA Newsletter, June 2000. Farmer Field Schools in Potato: A New Platform For Participatory Training and Research in The AndesDokument6 SeitenSubmitted To The ILEIA Newsletter, June 2000. Farmer Field Schools in Potato: A New Platform For Participatory Training and Research in The Andesraul_eloy_1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assessing the Risks and Opportunities of Trade in Wild Plant IngredientsVon EverandAssessing the Risks and Opportunities of Trade in Wild Plant IngredientsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pacific Regional Synthesis for the State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and AgricultureVon EverandPacific Regional Synthesis for the State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and AgricultureNoch keine Bewertungen

- Restoration in Action against Desertification: A Manual for Large-Scale Restoration to Support Rural Communities’ Resilience in the Great Green Wall ProgrammeVon EverandRestoration in Action against Desertification: A Manual for Large-Scale Restoration to Support Rural Communities’ Resilience in the Great Green Wall ProgrammeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thinking about the Future of Food Safety: A Foresight ReportVon EverandThinking about the Future of Food Safety: A Foresight ReportNoch keine Bewertungen

- RT Vol. 3, No. 1 NewsDokument2 SeitenRT Vol. 3, No. 1 NewsRice TodayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Farmers' RightsVon EverandFarmers' RightsNoch keine Bewertungen

- GrootDokument10 SeitenGrootIqbal ArrasyidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nsambya Organic Hub - Diphus - RNDokument9 SeitenNsambya Organic Hub - Diphus - RNliving businesseducationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effectiveness Review: Ruti Irrigation Project, ZimbabweDokument2 SeitenEffectiveness Review: Ruti Irrigation Project, ZimbabweOxfamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis On Food Security in KenyaDokument6 SeitenThesis On Food Security in Kenyapak0t0dynyj3100% (2)

- Agriculture and Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities at the Global and Local Level - Collaboration on Climate-Smart AgricultureVon EverandAgriculture and Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities at the Global and Local Level - Collaboration on Climate-Smart AgricultureNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1834 KochDokument7 Seiten1834 Kochkelvin8233Noch keine Bewertungen

- Project Design DocumentDokument14 SeitenProject Design Documentenock4warindaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainable Agriculture: A Tool To Strengthen Food Security and Nutrition in Latin America and The CaribbeanDokument48 SeitenSustainable Agriculture: A Tool To Strengthen Food Security and Nutrition in Latin America and The CaribbeanEVA OKTAVIANINoch keine Bewertungen

- Creating Resilient Livelihoods for Youth in Small-Scale Food Production: A Collection of Projects to Support Young People in Achieving Sustainable and Resilient Livelihoods and Food SecurityVon EverandCreating Resilient Livelihoods for Youth in Small-Scale Food Production: A Collection of Projects to Support Young People in Achieving Sustainable and Resilient Livelihoods and Food SecurityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forests for Human Health and Well-Being: Strengthening the Forest–Health–Nutrition NexusVon EverandForests for Human Health and Well-Being: Strengthening the Forest–Health–Nutrition NexusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Factors Influencing Farmers Adoption of Improved Rabbit Production Technologies: A Case of Nyamira County, KenyaDokument15 SeitenAnalysis of Factors Influencing Farmers Adoption of Improved Rabbit Production Technologies: A Case of Nyamira County, KenyaIOSRjournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence of Success: Climate-Smart Approaches To Smallholder Dairy Development in East AfricaDokument3 SeitenEvidence of Success: Climate-Smart Approaches To Smallholder Dairy Development in East AfricaEndale BalchaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Diseases and Control in Seaweed Farming in ZanzibarVon EverandUnderstanding Diseases and Control in Seaweed Farming in ZanzibarNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Sustainable Is Organic Agriculture in The Phils Rodel G. Maghirang Et AlDokument33 SeitenHow Sustainable Is Organic Agriculture in The Phils Rodel G. Maghirang Et AlianmaranonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 How Sustainable Is Organic Agriculture in The Phils Rodel G. Maghirang Et AlDokument33 Seiten4 How Sustainable Is Organic Agriculture in The Phils Rodel G. Maghirang Et AlNgan TuyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Papers On Food Security in KenyaDokument8 SeitenResearch Papers On Food Security in Kenyagzvp7c8x100% (1)

- Engaging Women and Men Equally in Managing Biodiversity: Guidelines to Address Gender Equality in Policies and Projects Related to BiodiversityVon EverandEngaging Women and Men Equally in Managing Biodiversity: Guidelines to Address Gender Equality in Policies and Projects Related to BiodiversityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computer PresentationDokument9 SeitenComputer PresentationDebmalyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Looking at Edible Insects from a Food Safety Perspective: Challenges and Opportunities for the SectorVon EverandLooking at Edible Insects from a Food Safety Perspective: Challenges and Opportunities for the SectorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biosecurity Practices Applied in Aquacultural Farms in Northern Senegal, West AfricaDokument14 SeitenBiosecurity Practices Applied in Aquacultural Farms in Northern Senegal, West AfricaMawdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tackling Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Food-Producing Animals: Lessons Learned in the United KingdomVon EverandTackling Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Food-Producing Animals: Lessons Learned in the United KingdomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact Assessment of Good Agricultural Practices of Vegetable Farmers at Three Barangays of Roxas, IsabelaDokument41 SeitenImpact Assessment of Good Agricultural Practices of Vegetable Farmers at Three Barangays of Roxas, IsabelaJacquiline NogalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainable Healthy Diets: Guiding PrinciplesVon EverandSustainable Healthy Diets: Guiding PrinciplesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Business of Plant Breeding: Market led Approaches to Plant Variety Design in AfricaVon EverandThe Business of Plant Breeding: Market led Approaches to Plant Variety Design in AfricaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis On Food Insecurity in KenyaDokument4 SeitenThesis On Food Insecurity in KenyaBuyingPaperCanada100% (2)

- Research Paper On Sustainable Agriculture Filetype PDFDokument7 SeitenResearch Paper On Sustainable Agriculture Filetype PDFafeaxlaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voluntary Guidelines for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Crop Wild Relatives and Wild Food PlantsVon EverandVoluntary Guidelines for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Crop Wild Relatives and Wild Food PlantsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Helvetas Impact Study On Organic and Fairtrade Cotton in Burkina Faso, 2008Dokument4 SeitenHelvetas Impact Study On Organic and Fairtrade Cotton in Burkina Faso, 2008Mitch TebergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scaling-Out and Scaling-Up AgroecologyDokument3 SeitenScaling-Out and Scaling-Up AgroecologyRamon kkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2018: Addressing the Threat from Climate Variability and Extremes for Food Security and NutritionVon EverandAfrica Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2018: Addressing the Threat from Climate Variability and Extremes for Food Security and NutritionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis On Food Security in Ethiopia PDFDokument11 SeitenThesis On Food Security in Ethiopia PDFfopitolobej3100% (2)

- Ecological Agriculture: Mitigating Climate Change, Providing Food Security & Self-Reliance For Rural Livelihoods in AfricaDokument16 SeitenEcological Agriculture: Mitigating Climate Change, Providing Food Security & Self-Reliance For Rural Livelihoods in AfricaGiaToula54Noch keine Bewertungen

- Regional Overview of Food Insecurity. Asia and the PacificVon EverandRegional Overview of Food Insecurity. Asia and the PacificNoch keine Bewertungen

- RT Vol. 5, No. 3 NewsDokument4 SeitenRT Vol. 5, No. 3 NewsRice TodayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agricultural Waste Diversity and Sustainability Issues: Sub-Saharan Africa as a Case StudyVon EverandAgricultural Waste Diversity and Sustainability Issues: Sub-Saharan Africa as a Case StudyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustaining Global Food Security: The Nexus of Science and PolicyVon EverandSustaining Global Food Security: The Nexus of Science and PolicyBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture and Food Systems in Practice: Options for InterventionVon EverandNutrition-Sensitive Agriculture and Food Systems in Practice: Options for InterventionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proceedings of the Fao International Symposium on the Future of Food: 10–11 June 2019Von EverandProceedings of the Fao International Symposium on the Future of Food: 10–11 June 2019Noch keine Bewertungen

- Addressing Gender Inequalities to Build Resilience: Stocktaking of Good Practices in the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ Strategic Objective 5Von EverandAddressing Gender Inequalities to Build Resilience: Stocktaking of Good Practices in the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ Strategic Objective 5Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Real Green Revolution Organic and Agroecological FarmingDokument151 SeitenThe Real Green Revolution Organic and Agroecological FarmingKlausEllegaard11Noch keine Bewertungen

- State Food Provisioning As Social ProtectionDokument80 SeitenState Food Provisioning As Social ProtectionJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

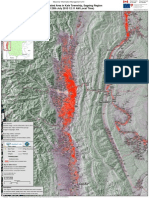

- Myanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Dokument1 SeiteMyanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of Potential WFP G2P Partner Programs in IndonesiaDokument34 SeitenAssessment of Potential WFP G2P Partner Programs in IndonesiaJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender Equality and Food Security: Women's Empowerment As A Tool Against HungerDokument114 SeitenGender Equality and Food Security: Women's Empowerment As A Tool Against HungerJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key Lessons From The Agriculture Response To Severe Tropical Cyclone PamDokument9 SeitenKey Lessons From The Agriculture Response To Severe Tropical Cyclone PamJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Myanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Dokument1 SeiteMyanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACAPS Briefing Note Myanmar Floods 6 Aug 2015Dokument6 SeitenACAPS Briefing Note Myanmar Floods 6 Aug 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- FES Country Gender Profile - MYANMARDokument18 SeitenFES Country Gender Profile - MYANMARJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIMU Hazard Map Mandalay-Magway Flood Area No. 3 29 Jul 2015Dokument1 SeiteMIMU Hazard Map Mandalay-Magway Flood Area No. 3 29 Jul 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- OCHA Myanmar: Myanmar Rainfall and River Level Forecast OCHA 04 Aug 2015Dokument1 SeiteOCHA Myanmar: Myanmar Rainfall and River Level Forecast OCHA 04 Aug 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vanuatu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report #5 23 Mar 2015Dokument2 SeitenVanuatu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report #5 23 Mar 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACAPS Report Southeast Asia Rohingya 07 Aug 2015Dokument9 SeitenACAPS Report Southeast Asia Rohingya 07 Aug 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hazard Map Myebon Kyaukphyu Ramrees Flood Area 03 Aug 2015 JPJXDokument1 SeiteHazard Map Myebon Kyaukphyu Ramrees Flood Area 03 Aug 2015 JPJXJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- WFP Myanmar External SitRep Flood Emergency Response 3 Aug 15Dokument2 SeitenWFP Myanmar External SitRep Flood Emergency Response 3 Aug 15Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- WFP Kenya's Transitional Cash Transfers To Schools (TCTS) : A Cash-Based Home Grown School Meals ProgrammeDokument4 SeitenWFP Kenya's Transitional Cash Transfers To Schools (TCTS) : A Cash-Based Home Grown School Meals ProgrammeJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Gender?Dokument5 SeitenWhy Gender?Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- UN SWAP Technical Notes Dec 2013Dokument69 SeitenUN SWAP Technical Notes Dec 2013Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Typhoon Haiyan Damage Summary Manila Philippines, Global Agriculture Information Netowrk (GAIN), USDA/FAS, Dec 4, 2013Dokument3 SeitenTyphoon Haiyan Damage Summary Manila Philippines, Global Agriculture Information Netowrk (GAIN), USDA/FAS, Dec 4, 2013Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Myanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Dokument1 SeiteMyanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- IFRC Strategic Framework On Gender and Diversity 2013-2020Dokument8 SeitenIFRC Strategic Framework On Gender and Diversity 2013-2020Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panay Island Rapid Market Assessment Report, World Vision, Nov 29, 2013Dokument16 SeitenPanay Island Rapid Market Assessment Report, World Vision, Nov 29, 2013Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panay Island Rapid Market Assessment Report, World Vision, Nov 29, 2013Dokument16 SeitenPanay Island Rapid Market Assessment Report, World Vision, Nov 29, 2013Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Dept of Agriculture Preliminary Estimates of Losses From Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) Nov 27, 2013Dokument12 SeitenPhilippines Dept of Agriculture Preliminary Estimates of Losses From Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) Nov 27, 2013Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- WFP 2012 Update of Safety Nets Policy - The Role of Food Assistance in Social ProtectionDokument29 SeitenWFP 2012 Update of Safety Nets Policy - The Role of Food Assistance in Social ProtectionJeffrey Marzilli100% (1)

- WFP Nutrition Policy 2012Dokument23 SeitenWFP Nutrition Policy 2012Jeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNHCR 2009 Policy On Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban AreasDokument30 SeitenUNHCR 2009 Policy On Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban AreasJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- WFP 2004 Nutrition in Emergencies WFP Experiences and ChallengesDokument17 SeitenWFP 2004 Nutrition in Emergencies WFP Experiences and ChallengesJeffrey MarzilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mead's Generalized Other DefinitionDokument2 SeitenMead's Generalized Other DefinitionArXlan XahirNoch keine Bewertungen

- EIA India TamilNaduDokument370 SeitenEIA India TamilNaduZaber Moinul100% (2)

- UNDP vs World Bank development criteria comparisonDokument2 SeitenUNDP vs World Bank development criteria comparisonShweta GajbhiyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tiger King NOTESDokument6 SeitenThe Tiger King NOTESDieHard TechBoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3 OPPORTUNITY SEEKING P1Dokument21 SeitenLesson 3 OPPORTUNITY SEEKING P1Hazel mae Kapangyarihan100% (1)

- UN Water Conference 2023 Analysis NoteDokument3 SeitenUN Water Conference 2023 Analysis NoteVlad AranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sewerage Tariff e PDFDokument2 SeitenSewerage Tariff e PDFDumindu De SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Mexico Ex Rel. Richardson v. BLM, 565 F.3d 683, 10th Cir. (2009)Dokument77 SeitenNew Mexico Ex Rel. Richardson v. BLM, 565 F.3d 683, 10th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aapda Samvaad - September, 2017Dokument10 SeitenAapda Samvaad - September, 2017Ndma IndiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wind Power Affirmative 2AC - SDI 2014Dokument268 SeitenWind Power Affirmative 2AC - SDI 2014lewa109Noch keine Bewertungen

- LM Project NBADokument19 SeitenLM Project NBARishabhMishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA Strategic Management Course OverviewDokument3 SeitenMBA Strategic Management Course Overviewmareg malgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Water Projects to Support 12 Rural SchoolsDokument6 SeitenCommunity Water Projects to Support 12 Rural SchoolsSireatu TadesseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Supply and Distribution System PDFDokument33 SeitenWater Supply and Distribution System PDFIgnacio Jr. PaguyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2006 - Enterprise Entrepreneurship and Innovation PDFDokument471 Seiten2006 - Enterprise Entrepreneurship and Innovation PDFMakbel100% (1)

- Noise PollutionDokument7 SeitenNoise PollutionRa PaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecofeminism, Social EcologyDokument14 SeitenEcofeminism, Social EcologyRebeka BorosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational Behavior Concept and AnalysisDokument4 SeitenOrganizational Behavior Concept and Analysisvnbio100% (1)

- Gut Feeling AnalysisDokument3 SeitenGut Feeling AnalysisRoy KogantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of The Implementation of R.A PDFDokument2 SeitenAssessment of The Implementation of R.A PDFJohn Gilbert GopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- C&D WasteDokument6 SeitenC&D WastesugunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JWT Future100 - 2020Dokument226 SeitenJWT Future100 - 2020Jacques ErasmusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Setbacks For Rivers and CreeksDokument20 SeitenSetbacks For Rivers and CreeksShriramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Engineering in Poverty ReductionDokument8 SeitenRole of Engineering in Poverty ReductionVarma AmitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Envsec Eastern EuropeDokument98 SeitenEnvsec Eastern Europeyanari2Noch keine Bewertungen

- DBQ Essay Example With Scoring ExplanationDokument4 SeitenDBQ Essay Example With Scoring ExplanationJoel TrogeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boone Kurtz - Expanded PPT - Ch02Dokument36 SeitenBoone Kurtz - Expanded PPT - Ch02VARGHESE JOSEPH NNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Inland Navigation InstituteDokument2 SeitenNational Inland Navigation Institutenini PatnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DM GM Improv Cheat SheetDokument4 SeitenDM GM Improv Cheat Sheetdinklesturge100% (2)

- The Republic of Rwanda Food Hygiene Regulation AmendedDokument16 SeitenThe Republic of Rwanda Food Hygiene Regulation Amendedmugabo bertinNoch keine Bewertungen