Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Early Concepts of Evolution Lamarck

Hochgeladen von

Lilian ChiuOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Early Concepts of Evolution Lamarck

Hochgeladen von

Lilian ChiuCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Early Concepts of Evolution: Jean Baptiste Lamarck

Darwin was not the first naturalist to propose that species changed over time

into new speciesthat life, as we would say now, evolves. In the eighteenth

century, Buffon and other naturalists began to introduce the idea that life

might not have been fixed since creation. By the end of the 1700s,

paleontologists had swelled the fossil collections of Europe, offering a picture of

the past at odds with an unchanging natural world. And in 1801, a French

naturalist named Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck

took a great conceptual step and proposed a full-blown theory of evolution.

Lamarck started his scientific career as a botanist, but in 1793 he became one of the founding

professors of the Musee National d'Histoire Naturelle as an expert on invertebrates. His work on

classifying worms, spiders, molluscs, and other boneless creatures was far ahead of his time.

Change through use and disuse

Lamarck was struck by the similarities of many of the

animals he studied, and was impressed too by the

burgeoning fossil record. It led him to argue that life was

not fixed. When environments changed, organisms had

to change their behavior to survive. If they began to use

an organ more than they had in the past, it would

increase in its lifetime. If a giraffe stretched its neck for

leaves, for example, a "nervous fluid" would flow into its

neck and make it longer. Its offspring would inherit the

longer neck, and continued stretching would make it

longer still over several generations. Meanwhile organs

that organisms stopped using would shrink.

Lamarck believed that the long necks of giraffes evolved as

generations of giraffes reached for ever higher leaves.

Organisms driven to greater complexity

This sort of evolution, for which Lamarck is most famous today, was only one of two mechanisms

he proposed. As organisms adapted to their surroundings, nature also drove them inexorably

upward from simple forms to increasingly complex ones. Like Buffon, Lamarck believed that life

had begun through spontaneous generation. But he claimed that new primitive life forms sprang

up throughout the history of life; today's microbes were simply "the new kids on the block."

Lamarck also proposed that organisms were driven from simple to increasingly more

complex forms.

Evolution by natural processes

Lamarck was mocked and attacked by Cuvier and many other naturalists of his day. While they

questioned him on scientific grounds, many of them were also disturbed by the theological

implications of his work. Lamarck was proposing that life took on its current form through natural

processes, not through miraculous interventions. For British naturalists in particular, steeped as

they were in natural theology, this was appalling. They believed that nature was a reflection of

God's benevolent design. To them, it seemed Lamarck was claiming that it was the result of blind

primal forces. Shunned by the scientific community, Lamarck died in 1829 in poverty and

obscurity.

But the notion of evolution did not die with him. The French naturalist Geoffroy St. Hilaire would

champion another version of evolutionary change in the 1820s, and the British writer Robert

Chambers would author a best-selling argument for evolution in 1844: Vestiges of a Natural

Creation. And in 1859, Charles Darwin would publish the Origin of Species.

Different from Darwin

In many ways, Darwin's central argument is very

different from Lamarck's. Darwin did not accept an

arrow of complexity driving through the history of life.

He argued that complexity evolved simply as a result

of life adapting to its local conditions from one

generation to the next. He also argued that species

could go extinct rather than change into new forms.

But Darwin also relied on much the same evidence for

evolution that Lamarck did (such as vestigial structures

and artificial selection through breeding). And Darwin wrongly accepted that changes acquired

during an organism's lifetime could be passed on to its offspring.

Lamarckian inheritance remained popular throughout the 1800s, in large part because scientists

did not yet understand how heredity works. With the discovery of genes, it was finally abandoned

for the most part. But Lamarck, whom Darwin described as "this justly celebrated naturalist,"

remains a major figure in the history of biology for envisioning evolutionary change for the first

time.

http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/_0/history_09

Jean Baptiste Lamarck:

Jean Baptiste Lamarck argued for a very different view of evolution than Darwin's. Lamarck

believed that simple life forms continually came into existence from dead matter and continually

became more complex -- and more "perfect" -- as they transformed into new species. Though his

views were eventually eclipsed by Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, modern scientists

have found some surprising examples of quasi-Lamarckian evolution

Although the name "Lamarck" is now associated with a discredited view of evolution, the French

biologist's notion that organisms inherit the traits acquired during their parents' lifetime had common

sense on its side. In fact, the "inheritance of acquired characters" continued to have supporters well

into the 20th century.

Jean Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) is one of the best-known early evolutionists. Unlike Darwin,

Lamarck believed that living things evolved in a continuously upward direction, from dead matter,

through simple to more complex forms, toward human "perfection." Species didn't die out in

extinctions, Lamarck claimed. Instead, they changed into other species. Since simple organisms exist

alongside complex "advanced" animals today, Lamarck thought they must be continually created by

spontaneous generation.

According to Lamarck, organisms altered their behavior in response to environmental change. Their

changed behavior, in turn, modified their organs, and their offspring inherited those "improved"

structures. For example, giraffes developed their elongated necks and front legs by generations of

browsing on high tree leaves. The exercise of stretching up to the leaves altered the neck and legs,

and their offspring inherited these acquired characteristics.

According to Darwin's theory, giraffes that happened to have slightly longer necks and limbs would

have a better chance of securing food and thus be able to have more offspring -- the "select" who

survive.

Conversely, in Lamarck's view, a structure or organ would shrink or disappear if used less or not at

all. Driven by these heritable modifications, all organisms would become adapted to their

environments as those environments changed.

Unlike Darwin, Lamarck held that evolution was a constant process of striving toward greater

complexity and perfection. Even though this belief eventually gave way to Darwin's theory of natural

selection acting on random variation, Lamarck is credited with helping put evolution on the map and

with acknowledging that the environment plays a role in shaping the species that live in it.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/library/02/3/l_023_01.html

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Lamarck Vs Darwin Reading HWDokument3 SeitenLamarck Vs Darwin Reading HWapi-274236035Noch keine Bewertungen

- Human Evolution TheoriesDokument11 SeitenHuman Evolution Theoriesranakhushboo1412Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lamarckism, The First Theory of Evolution: March 4, 2013 Marc Srour Leave A CommentDokument12 SeitenLamarckism, The First Theory of Evolution: March 4, 2013 Marc Srour Leave A CommentCMG RainNoch keine Bewertungen

- LamarckDokument1 SeiteLamarckGapmil Noziuc NylevujNoch keine Bewertungen

- LamarckDokument9 SeitenLamarckHANNA ANGELA LEJANONoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary & Study Guide - The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of LifeVon EverandSummary & Study Guide - The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre Darwinian TheoriesDokument5 SeitenPre Darwinian Theoriesmonster143Noch keine Bewertungen

- Project in Bio 4th QTRDokument7 SeitenProject in Bio 4th QTRKatrina PaquizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of EvolutionDokument3 SeitenTheories of EvolutionEbuka UjunwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Timeline of Evolutionary ThoughtDokument6 SeitenA Timeline of Evolutionary ThoughtSaji RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Once Upon A Science - A Tale of EvolutionDokument5 SeitenOnce Upon A Science - A Tale of EvolutionAU-JRC-SHS Evangeline MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charles DarwinDokument3 SeitenCharles DarwinSara Abanur-mal100% (1)

- Group 3Dokument12 SeitenGroup 3John LontocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay On The Evolving Beliefs On EvolutionDokument2 SeitenEssay On The Evolving Beliefs On Evolutionkeith herreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of EvolutionDokument3 SeitenTheories of EvolutionsophiegarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- L5 Development of Evolutionary Thought Lesson HandoutDokument9 SeitenL5 Development of Evolutionary Thought Lesson HandoutHannahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zoloogy Report BlindDokument8 SeitenZoloogy Report BlindBlind BerwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- From The Origin of Life To Evolutionary School of ThoughtDokument2 SeitenFrom The Origin of Life To Evolutionary School of ThoughtJunell TadinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lamarckism and Neo LamarckismDokument5 SeitenLamarckism and Neo LamarckismImran HussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Darwinian TheoryDokument15 SeitenDarwinian TheoryVivialyn BanguilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolution - A Historical PerspectiveDokument13 SeitenEvolution - A Historical PerspectiveRaphael MolanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 3Dokument6 SeitenGroup 3John LontocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atestat EnglezaDokument44 SeitenAtestat EnglezaCarmen OlteanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- DarwinvlamarckDokument2 SeitenDarwinvlamarckapi-316869376Noch keine Bewertungen

- Charles Darwin's "Origin of Species" Is Published - HISTORY: Nekoliko Brzih ČinjenicaDokument5 SeitenCharles Darwin's "Origin of Species" Is Published - HISTORY: Nekoliko Brzih ČinjenicaElvedin SabanovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolution I & IIDokument30 SeitenEvolution I & IIAyesha RamzanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Darwin Evolution RevisedDokument111 SeitenDarwin Evolution RevisedCheskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept of LifeDokument11 SeitenConcept of LifeLiezl Cutchon CaguiatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jean-Baptiste Lamarck - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDokument5 SeitenJean-Baptiste Lamarck - Britannica Online Encyclopediahairil haqeemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 2Dokument15 SeitenLecture 2listoproNoch keine Bewertungen

- Local Media447164416071102402Dokument32 SeitenLocal Media447164416071102402Maria Zeny OrtegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- For BioDokument5 SeitenFor BioAika Mae ArakakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Darwin and Evolution 6.1 - StudentsDokument37 SeitenDarwin and Evolution 6.1 - StudentsMahra AlketbiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Booc, Johnren G. (Theory of Darwin & Lamarck)Dokument1 SeiteBooc, Johnren G. (Theory of Darwin & Lamarck)Johnren Godinez BoocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of Use and DisuseDokument19 SeitenTheory of Use and DisuseYosh Zabala IV0% (1)

- GENBIOTDokument20 SeitenGENBIOTKing KayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer Bio Lec (Recent)Dokument3 SeitenReviewer Bio Lec (Recent)Louiza Angelina LayugNoch keine Bewertungen

- Earth and Life Science. Chapter 10Dokument18 SeitenEarth and Life Science. Chapter 10veronicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes EvolutionDokument6 SeitenNotes EvolutionSunoo KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of Evolution PDFDokument23 SeitenTheories of Evolution PDFDivine GhagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of Evolution by Natural SelectionDokument15 SeitenTheory of Evolution by Natural Selectionpaula nicolle mostoles100% (1)

- Development of Evolutionary ThoughtDokument9 SeitenDevelopment of Evolutionary Thoughtkaren milloNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd Sem Q1 Week 3 Lesson 2 Development of Evolutionary ThoughtDokument26 Seiten2nd Sem Q1 Week 3 Lesson 2 Development of Evolutionary Thoughtayesha iris matillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Darwins Theory of EvolutionDokument5 SeitenWhat Is Darwins Theory of EvolutionRakesh MeherNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Basics of Evolution - Anne WanjieDokument135 SeitenThe Basics of Evolution - Anne Wanjienadine marchandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cob-Ch11 EvolutionDokument36 SeitenCob-Ch11 EvolutiongaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lamarckism: Lamarckism, or Lamarckian Inheritance, Also Known As "Neo-Lamarckism"Dokument30 SeitenLamarckism: Lamarckism, or Lamarckian Inheritance, Also Known As "Neo-Lamarckism"123aaabdNoch keine Bewertungen

- SB 17 EvolutionDokument36 SeitenSB 17 EvolutionGeo GeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life Heritable Traits Biological Populations Generations Biological Organisation Species Organisms MoleculesDokument8 SeitenLife Heritable Traits Biological Populations Generations Biological Organisation Species Organisms MoleculesCMG RainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolution Theories 2012Dokument43 SeitenEvolution Theories 2012Antonio López JiménezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of EvolutionDokument34 SeitenTheories of Evolutionren whahahhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life in The Past - Evolution: Darshil ShahDokument1 SeiteLife in The Past - Evolution: Darshil Shahoiu7hjjsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolution Notes 09Dokument23 SeitenEvolution Notes 09Merve ÖzkayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 22 EvolutionDokument32 Seiten22 EvolutionTazneen Hossain TaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of RevolutionDokument22 SeitenTheories of Revolutionpink_20Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Story of Life in 25 Fossils: Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of EvolutionVon EverandThe Story of Life in 25 Fossils: Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of EvolutionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Click Here To Enter TextDokument20 SeitenClick Here To Enter Textspranesh409Noch keine Bewertungen

- False Evidence of Evolution - 2: The Miller ExperimentDokument10 SeitenFalse Evidence of Evolution - 2: The Miller ExperimentHarunyahya EnglishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of EvolutionDokument18 SeitenTheories of EvolutionLakshmi Narayanan100% (1)

- Genbio2 - 3rd Quarter Final OutputDokument4 SeitenGenbio2 - 3rd Quarter Final OutputTrisha Mae UmallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stoddard, Lothrop - The Revolt Against Civilization. The Menace of The Under-ManDokument16 SeitenStoddard, Lothrop - The Revolt Against Civilization. The Menace of The Under-Manoddone9195Noch keine Bewertungen

- 3rdgrad NOTES GeneticsDokument3 Seiten3rdgrad NOTES GeneticsKarl SiaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavior Genetics and Postgenomics PDFDokument84 SeitenBehavior Genetics and Postgenomics PDFvkarmoNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Thomas A. Romberg, Thomas P. Carpenter, Fae Dremo (BookFi)Dokument349 Seiten(Thomas A. Romberg, Thomas P. Carpenter, Fae Dremo (BookFi)Rita Fajriati100% (1)

- The Gene An Intimate HistoryDokument2 SeitenThe Gene An Intimate HistoryrhythmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science Chapter 3 Form 4Dokument16 SeitenScience Chapter 3 Form 4Muhammad Akmal Kamaluddin100% (1)

- All Kerala Bhavans Biology 2010Dokument14 SeitenAll Kerala Bhavans Biology 2010SajeevNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIOC15H3F-2023 Fall Syllabus-20230817Dokument8 SeitenBIOC15H3F-2023 Fall Syllabus-20230817박정원Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bernadette Baker 2 2Dokument26 SeitenBernadette Baker 2 2Zé de RochaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology Ch. 11 Use This OneDokument66 SeitenBiology Ch. 11 Use This Oneمعروف عاجلNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tips - Essential Evolutionary Psychology PDFDokument281 SeitenTips - Essential Evolutionary Psychology PDFRadhey Surve100% (1)

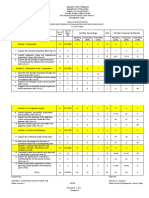

- Table of Specs 4th Quarter in Grade 8 ScienceDokument2 SeitenTable of Specs 4th Quarter in Grade 8 ScienceRaquelSalvadorMallari100% (3)

- Mendelian InheritanceDokument39 SeitenMendelian InheritancemrmoonzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research The FollowingDokument4 SeitenResearch The FollowingGenesis PalangiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Growth & Development - Dr. Ismail ThamarasseriDokument36 SeitenGrowth & Development - Dr. Ismail ThamarasseriParado Cabañal Skyliegh100% (1)

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Biol1318.001 05f Taught by Lee Bulla (Bulla)Dokument1 SeiteUT Dallas Syllabus For Biol1318.001 05f Taught by Lee Bulla (Bulla)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- MHT CET Biology Class XI and XII SyllabusDokument4 SeitenMHT CET Biology Class XI and XII SyllabusAkshayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uts Group2 Report 1Dokument35 SeitenUts Group2 Report 1Angela CjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henrik Ibsens Ghosts A Critical Study of Hereditary GeneticsDokument6 SeitenHenrik Ibsens Ghosts A Critical Study of Hereditary GeneticsfitranaamaliahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 3Dokument33 SeitenGrade 3mary antonette pagalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Biology Eng 2023 24Dokument3 Seiten12 Biology Eng 2023 24Rohan MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gene TherapyDokument29 SeitenGene TherapypriyankaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rat Genomics (001-095)Dokument103 SeitenRat Genomics (001-095)Cristina Hernandez PastranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Psychology: The Biological Basis of BehaviorDokument79 SeitenUnderstanding Psychology: The Biological Basis of Behaviormonster40lbsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 - Introduction To EcologyDokument6 SeitenModule 1 - Introduction To EcologyNelzen GarayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sci ReflectionDokument2 SeitenSci ReflectionLyden PeraltaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gen IticsDokument148 SeitenGen Iticskb gagsNoch keine Bewertungen

- NEET Biology SyllabusDokument8 SeitenNEET Biology SyllabusNaveen KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Behavior AnswersDokument3 SeitenHuman Behavior AnswerszanibabNoch keine Bewertungen