Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Beginning The Academic Essay

Hochgeladen von

sav0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

40 Ansichten4 Seitenhow to write an essay

Originaltitel

Beginning the Academic Essay

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenhow to write an essay

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

40 Ansichten4 SeitenBeginning The Academic Essay

Hochgeladen von

savhow to write an essay

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 4

BeginningtheAcademicEssay

The writer of the academic essay aims to persuade

readers of an idea based on evidence. The beginning

of the essay is a crucial first step in this process. In

order to engage readers and establish your authority,

the beginning of your essay has to accomplish certain

business. Your beginning should introduce the essay,

focus it, and orient readers.

Introduce the Essay.The beginning lets your

readers know what the essay is about, thetopic. The

essay's topic does not exist in a vacuum, however;

part of letting readers know what your essay is about

means establishing the essay'scontext, the frame

within which you will approach your topic. For

instance, in an essay about the First Amendment

guarantee of freedom of speech, the context may be

a particular legal theory about the speech right; it

may be historical information concerning the writing

of the amendment; it may be a contemporary

dispute over flag burning; or it may be a question

raised by the text itself. The point here is that, in

establishing the essay's context, you are also limiting

your topic. That is, you are framing an approach to

your topic that necessarily eliminates other

approaches. Thus, when you determine your context,

you simultaneously narrow your topic and take a big

step toward focusing your essay. Here's an example.

When Kate Chopin's novelThe

Awakeningwas published in 1899,

critics condemned the book as

immoral. One typical critic, writing in

theProvidence Journal, feared that the

novel might "fall into the hands of

youth, leading them to dwell on things

that only matured persons can

understand, and promoting unholy

imaginations and unclean desires"

(150). A reviewer in theSt. Louis Post

Dispatchwrote that "there is much that

is very improper in it, not to say

positively unseemly."

The paragraph goes on. But as you can see, Chopin's

novel (the topic) is introduced in the context of the

critical and moral controversy its publication

engendered.

Focus the Essay.Beyond introducing your topic,

your beginning must also let readers know what the

central issue is. What question or problem will you

be thinking about? You can pose a question that will

lead to your idea (in which case, your idea will be

the answer to your question), or you can make a

thesis statement. Or you can do both: you can ask a

question and immediately suggest the answer that

your essay will argue. Here's an example from an

essay about Memorial Hall.

Further analysis of Memorial Hall, and

of the archival sources that describe

the process of building it, suggests that

the past may not be the central subject

of the hall but only a medium. What

message, then, does the building

convey, and why are the fallen soldiers

of such importance to the alumni who

built it? Part of the answer, it seems,

is that Memorial Hall is an educational

tool, an attempt by the Harvard

community of the 1870s to influence

the future by shaping our memory of

their times. The commemoration of

those students and graduates who died

for the Union during the Civil War is

one aspect of this alumni message to

the future, but it may not be the

central idea.

The fullness of your idea will not emerge until your

conclusion, but your beginning must clearly indicate

the direction your idea will take, must set your essay

on that road. And whether you focus your essay by

posing a question, stating a thesis, or combining

these approaches, by the end of your beginning,

readers should know what you're writing about,

andwhyand why they might want to read on.

Orient Readers.Orienting readers, locating them in

your discussion, means providing information and

explanations wherever necessary for your readers'

understanding. Orienting is important throughout

your essay, but it is crucial in the beginning. Readers

who don't have the information they need to follow

your discussion will get lost and quit reading. (Your

teachers, of course, will trudge on.) Supplying the

necessary information to orient your readers may be

as simple as answering the journalist's questions of

who, what, where, when, how, and why. It may

mean providing a brief overview of events or a

summary of the text you'll be analyzing. If the source

text is brief, such as the First Amendment, you

might just quote it. If the text is well known, your

summary, for most audiences, won't need to be more

than an identifying phrase or two:

InRomeo and Juliet, Shakespeare's

tragedy of `starcrossed lovers'

destroyed by the blood feud between

their two families, the minor

characters . . .

Often, however, you will want to summarize your

source more fully so that readers can follow your

analysis of it.

Questions of Length and Order.How long should

the beginning be? The length should be

proportionate to the length and complexity of the

whole essay. For instance, if you're writing a five

page essay analyzing a single text, your beginning

should be brief, no more than one or two

paragraphs. On the other hand, it may take a couple

of pages to set up a tenpage essay.

Does the business of the beginning have to be

addressed in a particular order? No, but the order

should be logical. Usually, for instance, the question

or statement that focuses the essay comes at the end

of the beginning, where it serves as the jumpingoff

point for the middle, or main body, of the essay.

Topic and context are often intertwined, but the

context may be established before the particular

topic is introduced. In other words, the order in

which you accomplish the business of the beginning

is flexible and should be determined by your

purpose.

Opening Strategies.There is still the further

question of how to start. What makes a good

opening? You can start with specific facts and

information, a keynote quotation, a question, an

anecdote, or an image. But whatever sort of opening

you choose, it should be directly related to your

focus. A snappy quotation that doesn't help establish

the context for your essay or that later plays no part

in your thinking will only mislead readers and blur

your focus. Be as direct and specific as you can be.

This means you should avoid two types of openings:

The historyoftheworld (or longdistance)

opening, which aims to establish a context for the

essay by getting a long running start: "Ever since

the dawn of civilized life, societies have struggled

to reconcile the need for change with the need

for order." What are we talking about here,

political revolution or a new brand of soft drink?

Get to it.

The funnel opening (a variation on the same

theme), which starts with something broad and

general and "funnels" its way down to a specific

topic. If your essay is an argument about state

mandated prayer in public schools, don't start by

generalizing about religion; start with the specific

topic at hand.

Remember.After working your way through the

whole draft, testing your thinking against the

evidence, perhaps changing direction or modifying

the idea you started with, go back to your beginning

and make sure it still provides a clear focus for the

essay. Then clarify and sharpen your focus as

needed. Clear, direct beginnings rarely present

themselves readymade; they must be written, and

rewritten, into the sort of sharpeyed clarity that

engages readers and establishes your authority.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Rasi Navamsa: Me Su Ve Ke As Ve (Sa) KeDokument11 SeitenRasi Navamsa: Me Su Ve Ke As Ve (Sa) KesavNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- LazyDokument1 SeiteLazysavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- A Champion Is Never Afraid of The Losses and Failures He Knows That Failure Is A Stepping Stone of SuccessDokument1 SeiteA Champion Is Never Afraid of The Losses and Failures He Knows That Failure Is A Stepping Stone of SuccesssavNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- There Are Many Many Options in Life SoDokument2 SeitenThere Are Many Many Options in Life SosavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Planets Governing The DaysDokument1 SeitePlanets Governing The DayssavNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Prefab IntroductionDokument20 SeitenPrefab IntroductionsavNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Gktest May 1Dokument3 SeitenGktest May 1savNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Savita Halappanavar: Persons in News: Gktoday Current Affairs E Books Downloads Gs Manual 2014 Test Series (Prelims) 2015Dokument2 SeitenSavita Halappanavar: Persons in News: Gktoday Current Affairs E Books Downloads Gs Manual 2014 Test Series (Prelims) 2015savNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Aadi KoozhDokument1 SeiteAadi KoozhsavNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Dus Mahavidya Shabar Mantra Sadhana (दस महाविद्या शाबर मंत्र साधना एवं सिद्धि)Dokument23 SeitenDus Mahavidya Shabar Mantra Sadhana (दस महाविद्या शाबर मंत्र साधना एवं सिद्धि)Gurudev Shri Raj Verma ji90% (10)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Impact of The Interfaith Program On The PDL at The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology in ButuanDokument7 SeitenImpact of The Interfaith Program On The PDL at The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology in ButuanRazzie Emata0% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Nativity Prayer DirectiveDokument2 SeitenNativity Prayer Directivechelsea_kingstonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- EC PresentationDokument16 SeitenEC PresentationSharanya NadarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Objectives and Characteristics of Islamic AccountingDokument29 SeitenObjectives and Characteristics of Islamic AccountingHafis ShaharNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Nature of The ConstitutionDokument17 SeitenNature of The ConstitutionGrace MugorondiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dattaatreya UpanishadDokument4 SeitenDattaatreya UpanishadXynofobNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- OPPT Definitions PDFDokument2 SeitenOPPT Definitions PDFAimee HallNoch keine Bewertungen

- Southeastern Program - Master of Divinity, M.divDokument2 SeitenSoutheastern Program - Master of Divinity, M.divElliot DuenowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Cosmological Symbolism in The Initial Canberra Plan Peter R. ProudfootDokument31 SeitenAncient Cosmological Symbolism in The Initial Canberra Plan Peter R. ProudfootAdriano Piantella100% (1)

- Prehispanic PeriodDokument11 SeitenPrehispanic PeriodDaryl CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 63.Dokument738 SeitenMigne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 63.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chaffee, 3e Chapter 8Dokument53 SeitenChaffee, 3e Chapter 8Bradford McCallNoch keine Bewertungen

- 999 SACRED KUNDALINI 52019 HW PDFDokument10 Seiten999 SACRED KUNDALINI 52019 HW PDFЕлена Александровна ЛавренкоNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Tribute To ParentsDokument2 SeitenSample Tribute To ParentsYES O DavNorNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Skanda Sashti KavachamDokument19 SeitenSkanda Sashti Kavachamravi_naNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Kenosis and Christology - An - Paul D. FeinbergDokument27 SeitenThe Kenosis and Christology - An - Paul D. FeinbergRichard Mayer Macedo SierraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 201 - Agamas in Sri Vaishnavism - AgamaDokument50 Seiten201 - Agamas in Sri Vaishnavism - AgamaVinu GeorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 Conditions of ShahadaDokument2 Seiten9 Conditions of ShahadaQubeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shamanism Archaic Techniques of EcstasyDokument3 SeitenShamanism Archaic Techniques of Ecstasysatuple66Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Pamela E. Cayabyab BSA 3DDokument2 SeitenPamela E. Cayabyab BSA 3DDioselle CayabyabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bible Quiz Questions-Acts 1Dokument2 SeitenBible Quiz Questions-Acts 1iamdeboz100% (2)

- 07-05-14 EditionDokument28 Seiten07-05-14 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Origin of Targum JonathanDokument8 SeitenOrigin of Targum JonathansurfprivatelyNoch keine Bewertungen

- French Court ArtDokument7 SeitenFrench Court ArtMariam GomaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Garces V Estenzo - DIGESTDokument1 Seite7 Garces V Estenzo - DIGESTMarga Lera100% (1)

- Spiritual Guru Who Actually Helped The HumanityDokument4 SeitenSpiritual Guru Who Actually Helped The HumanitySoundararajan SeeranganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- College of Teacher Education: "I Wish I Could Persuade Every Teacher To Be Proud of His Occupation"Dokument3 SeitenCollege of Teacher Education: "I Wish I Could Persuade Every Teacher To Be Proud of His Occupation"Ria Mateo60% (5)

- SkedzuhnSafir Etal 2021Dokument248 SeitenSkedzuhnSafir Etal 2021ivancov catalinNoch keine Bewertungen

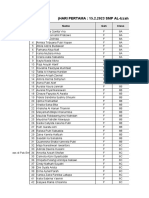

- Senarai Nama Buddy TerkiniDokument14 SeitenSenarai Nama Buddy TerkiniYap Yu SiangNoch keine Bewertungen