Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Influence of Parents' Oral Health

Hochgeladen von

Manjeev GuragainOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Influence of Parents' Oral Health

Hochgeladen von

Manjeev GuragainCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

IPD_338.

fm Page 101 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 2002; 12: 101108

Influence of parents oral health behaviour on oral health

status of their school children: an exploratory study

employing a causal modelling technique

Blackwell Science Ltd

M. OKADA1, M. KAWAMURA2, Y. KAIHARA1, Y. MATSUZAKI1,

S. KUWAHARA1, H. ISHIDORI1 & K. MIURA1

1Department

of Paediatric Dentistry and 2Department of Preventive Dentistry,

Hiroshima University Faculty of Dentistry, Minami-ku, Hiroshima, Japan

Summary. Objectives. The aim of this study was to examine the simultaneous interrelationships between parents oral health behaviour and the oral health status of their

school children.

Sample and methods. Subjects comprized 296 pairs of parents (mother or father) and

their children at an elementary school in Hiroshima. The childs dental examination

was performed using the World Health Organization (WHO) caries diagnostic criteria

for decayed teeth (DT) and filled teeth (FT). The Oral Rating Index for Children (ORIC) was used for the childs gingival health examination. Hiroshima University Dental

Behavioural Inventory (HU-DBI) was used for the assessment of the parents oral health

behaviour. A parent child behavioural model was tested by the linear structural relations

(LISREL) programme.

Results. There was a significant correlation between DT and ORI-C (r = 0168; P < 001).

Correlation was found between ORI-C and oral health behaviour in children (OHB-C)

(r = 0182; P < 001). OHB-C was significantly associated with the HU-DBI (r = 0251;

P < 0001). The hypothesized model after some revisions was found to be consistent

with the data (2 = 13, d.f. = 6, P = 097; Goodness of Fit Index = 0999). Parents

oral health behaviour affected their childrens oral health behaviour (P < 0001). Childrens oral health behaviour affected their DT through its effect on gingival health level.

Parents oral health behaviour also had a significant direct effect on their childrens

DT (P < 005). Childrens grade affected both DT and their oral health behaviour.

Conclusions. Parents oral health behaviour could influence their childrens gingival

health and dental caries directly and/or indirectly through its effect on childrens oral

health behaviour.

Introduction

Adoption of consistent behavioural habits in childhood

takes place at home, with the parents, especially the

Correspondence: Dr Mitsugi Okada, Department of Paediatric

Dentistry, Hiroshima University Faculty of Dentistry, 12-3

Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 7348553, Japan. E-mail:

mitsugi@hiroshima-u.ac.jp

2002 BSPD and IAPD

mother, being the primary model for behaviour [1].

To prevent dental caries and gingivitis, a mothers

support is essential. Sasahara et al. [2] showed that

mothers gingival condition, as a result of oral

health behaviour, was associated with the prevalence

and severity of dental caries in their 3-year-old

children. Sarnat et al. [3] also reported that, at the

ages of 5 to 6 years, the more positive the mothers

attitude regarding her child, the fewer caries the

101

IPD_338.fm Page 102 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

102

M. Okada et al.

child had, the better the childs oral hygiene, and

the more dental treatment the child received. There

are few studies of parents influence on gingival

health of their school children by stage of childhood

development. It has been reported that, although

school children believed that appropriate behaviours

could promote health, they did not develop an

awareness of this relationship until the third and

fourth grade [4]. From the point of view of Banduras

social cognitive theory [5], overt behaviours of

significant others represent important sources of

social influence.

Socialization to oral health behaviours may be

considered a modelling process in which children

imitate the behaviour of their parents, who are available and who provide valued role models for their

offspring [5]. Parental modelling has proved to be

a powerful means of establishing novel behaviours

among children, such as tooth brushing behaviour

[6], but has rarely been studied as a behavioural

factor with simultaneous interrelationships among

variables of oral diseases.

Linear structural relations (LISREL) analysis

provides an opportunity to evaluate an entire set of

relationships at the same time [7]. It has several

advantages over traditional statistical methods, particularly as it explores the causal links rather than

mere empirical relationships between variables. In

addition, knowledge of the methodological adequacy

of the data-gathering process and the quality of measurement instruments can be directly incorporated

into LISREL models by estimating the proportion of

the variance in an indicator that is error variance.

The aim of the present study was to examine the

simultaneous interrelationships between parents

oral health behaviour and oral health status of their

school children by using the LISREL.

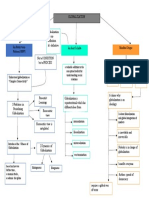

Theoretical model

The construction of a hypothesized model (Fig. 1)

is based on the findings of earlier studies [16,813]

of factors affecting oral health. It was hypothesized

that parents oral health behaviour is linked to oral

health status (dental caries and gingivitis) of their

school children directly, or indirectly through childrens oral health behaviour. It was hypothesized

that dental caries of school children are causally

linked to their gingival health level, which reflects

oral hygiene status (self-care level). Children with

poorly controlled oral hygiene would suffer signi-

Fig. 1. Construction of a hypothesized model. Influence of

parents oral health behaviour on both oral health behaviour and

oral health status of their school children.

ficantly more from tooth decay than those with good

control. It was hypothesized that childrens grade

and decayed teeth had direct effects on the number

of filled teeth.

Sample and methods

The study was conducted at an elementary school

in 1998 among a sample of 712-year-old children

in Hiroshima, Japan. Consent for this survey was

received from their parents prior to the study through

their schoolteachers. The parent (either mother or

father) was asked to answer a questionnaire about

the oral health behaviour of his/her child (OHB-C).

Five items in the OHB-C concerned daily brushing,

brushing frequency, use of floss, regular dental visit

and regular snack-time (Table 1). For each item, the

appropriate response was determined through

consideration of current information about the topic

addressed by the item. A higher score indicates

better dental health behaviour of children. The

Hiroshima University Dental Behavioural Inventory

(HU-DBI) [14] was used for the assessment of

parents oral health behaviour. The maximum score

of the HU-DBI was 12. A higher score indicates

better oral health behaviour. It has been shown to

be internally consistent (Cronbachs alpha = 076)

[15]. The HU-DBI had a good testretest reliability

(073) over a 4-week period [16]. Three hundred and

eight parents (mother or father) responded to this survey. The participation rate was 76%. Ten parents did

not complete the HU-DBI questions. The mother to

father ratio in the participants was 13 : 2. The mean

age of the parents was 377 years (standard deviation:

44 years).

2002 BSPD and IAPD, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12: 101108

IPD_338.fm Page 103 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

Parents influence childrens oral health

103

Table 1. Percentage distribution of the parents with agree responses for each item on childrens oral health behaviour (OHB-C).

No.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Item descriptions

My

My

My

My

My

child

child

child

child

child

brushes his/ her teeth every day (A)

brushes his/ her teeth more than twice a day (A)

never uses dental floss (D)

goes to see the dentist periodically (A)

has a snack at a certain time every day (A)

Boys

(n = 148)

Girls

(n = 148)

Chi-square

test

Total

(n = 296)

81

71

84

26

49

88

83

84

32

43

NS

*

NS

NS

NS

84

77

84

29

46

In the calculation of the OFIB-C: (A)One point is given for each of these agree responses. (D)One point is given for each of these

disagree responses. Cronbachs alpha = 051. Significant differences between boys and girls; *P < 005, NS = not significant.

Oral examinations took place at school for all

children, with the exception of two who were absent

from school. The ORI-C, which consists of five categories (+2, +1, 0, 1, 2), was used for gingival

health examination as previously described [17]. It

was performed by a paediatric dentist (MO), using

natural light with children seated in a chair, with a

set of standard photographs of each level of the

scale to maintain consistent standards. Next, the

children were dentally examined by three specialist

paediatric dentists (YK, SK, HI) using the World

Health Organization (WHO) caries diagnostic criteria for DMFT (decayed teeth, missing teeth, filled

teeth) [18]. The examination took place with the

subjects in a supine position, using an artificial light,

a dental explorer and a dental mirror. The mean percentage agreement among the dentists was more

than 90% (YK versus SK 92%, SK versus HI 95%,

HI versus YK 91%) for the inter-examiner reproducibility for DMFT criteria in a sample of 20 elementary school children. Subjects included 296 pairs

out of 406 parents and their children (213 boys and

193 girls). Thirty-nine fathers and one person who

did not report his/her sex distinction were included

among 296 respondents.

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and correlation coefficients were used to provide preliminary information about the associations

between six selected parameters. All paths connecting

the error components were set to unity. The overall

fit was assessed by four measures: the chi-square

test, the goodness of fit index (GFI), the adjusted

goodness of fit index (AGFI) and the root mean

square error of approximation (RMSEA). In this

study, the quality of model fit was considered reasonable, with the probability of a greater chi-square

value than the obtained values not less than 005,

GFI (AGFI) greater than 090 and, after standardization, RMSEA less than 005. Statistical analyses

were conducted using SPSS 100 J and Amos 40

(SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA; SmallWaters

Co., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Table 1 presents the percentage distribution of the

parents with agree responses for each item on the

OHB-C, for the total sample, and boys and girls

separately. More than 80% of the parents reported

that their child brushed his/ her teeth everyday.

However, 84% stated that their child had never used

dental floss. Only 29% reported that their child went

to see the dentist periodically. Table 2 shows

descriptive statistics of and correlation coefficients

among six selected variables. The mean scores of

DT, FT, OHB-C and HU-DBI were 037, 193, 250

and 500, respectively. Cronbachs alpha was 051

for the OHB-C. There was a significant correlation

between DT and ORI-C (r = 0168; P < 001).

Correlation was found between ORI-C and OHB-C

(r = 0182; P < 001). OHB-C was significantly

associated with HU-DBI (r = 0251; P < 0001).

When the initial model was estimated, the chisquare was 139 ( d.f. = 6, P = 003), suggesting that

the model did not fit the data. LISREL diagnostic

information led us to allow the childs grade to

affect his/ her oral health behaviour. Although no

direct path was initially hypothesized from childs

grade to DT, LISRELs modification index also

suggested this, so that the path linking grade to DT

was added. With these changes, the overall revised

model was judged to be satisfactory (2 = 13;

d.f. = 6, P = 097, GFI = 0999, AGFI = 0995,

RMSEA = 0000). The outline of our final model is

given in Fig. 2. Parents oral health behaviour had

a negative direct path to DT (014, P < 005) and

also had an indirect effect on childs gingival health

through childs oral health behaviour. It was found

2002 BSPD and IAPD, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12: 101108

IPD_338.fm Page 104 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

104

M. Okada et al.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of and correlations among six selected variables.

n

Mean

SD

Grade

DT

FT

ORI-C

OHB-C

HU-DBI

Grade

DT

FT

ORI-C

OHB-C

HU-DBI

296

351

172

1

0139*

0466***

0052

0158**

0011

296

037

102

296

193

192

296

008

092

296

250

125

296

500

216

1

0119*

0168**

0073

0153**

1

0005

0103

0002

1

0182**

0079

1

0251***

Grade = childs school grade; DT = the number of decayed teeth; FT = the number of filled teeth; ORI-C = oral rating index for children;

OHB-C = childs oral health behaviour; HU-DBI = parents oral health behaviour. Pearsons correlation coefficient (*P < 005, **P < 001,

***P < 0001).

Fig. 2. Outline of the final model. Childs

grade = childs school grade; decayed

teeth = childs number of decayed teeth;

filled teeth = childs number of filled teeth;

gingival health = score assessed by the

ORI-C; childs oral health behaviour =

OHB-C score; parents oral health behaviour = HU-DBI score. The overall fit was

assessed by four measures: chi-square test,

GFI (goodness of fit index), AGFI (adjusted

goodness of fit index) and RMSEA (root

mean square error of approximation). The

standardized regression weights are displayed

near single-headed arrows in the path diagram.

*P < 005, **P < 001, ***P < 0001.

that childs gingival health had a negative effect on

DT (015, P < 001) and that DT had a negative

effect on FT (019, P < 0001). Childs grade had

a positive effect on FT (049, P < 0001). Childs

oral health behaviour did not have any significant

effect on DT. In addition, the direct effect of

parents oral health behaviour on childs gingival

health was not significant. Further, the sign of the

coefficient for the association between childs grade

and oral health behaviour was negative (016,

P < 001). There were some striking differences for

the values of model parameters for the genders

(Figs 3 and 4), although the same model fitted the

data well for boys and for girls. For boys, parents

oral health behaviour had a significant effect on DT

(017, P < 005), whereas for girls it was not significant. Conversely, for boys their gingival health did

not have any significant effect on DT, whereas for

girls it was significant (018, P < 005).

Discussion

The results of this study showed that parents oral

health behaviour had a direct influence on their

childrens number of decayed teeth. Furthermore,

parents oral health behaviour had an indirect effect

on gingival health level of their children through

childrens own oral health behaviour. The finding is

in agreement with those of Sasahara et al. [2], Sarnat

et al. [3] and strom & Jakobsen [9], who reported

a significant correlation between parental oral health

behaviour and their childs oral health behaviour.

The findings of this study support the importance

of the continued emphasis on parents self-care

strategies for not only their oral health but also their

childrens oral health. Sallis & Nader [8] presented

a conceptual model of family influences on health

behaviour. The model comprizes four major components: (i) the family environment and interrelationships

2002 BSPD and IAPD, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12: 101108

IPD_338.fm Page 105 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

Parents influence childrens oral health

105

Fig. 3. Outline of the final model (boys). Illustration

legends are the same as those in Fig. 2.

Fig. 4. Outline of the final model (girls). Illustration

legends are the same as those in Fig. 2.

between health behaviours of the family members; (ii) the antecedents and consequences of

health behaviours; (iii) the influential mechanisms,

namely response facilitation, observational learning

and observation of consequences; and (iv) external

influences.

strom & Jakobsen [9] also reported that there

were statistically significant associations of use of

dental floss, tooth brushing and drinking of nonsugared mineral water among parents and their

adolescent offspring. Stewart et al. [10] showed that

there was a statistically significant increase in selfefficacy for brushing and flossing following psychological interventions to improve oral hygiene

behaviour. In Japan, most people do not know how

to use dental floss [19,20]. Although the role of

social cognitive variables on oral hygiene behaviour

(the daily removal of dental plaque by brushing and

flossing) has received little research attention in Japan,

children who have been encouraged in their preventive health behaviour may have self-efficacy during

growth and development. In this study, parents oral

health behaviour had a direct effect on DT for boys,

whereas for girls it had an indirect effect on DT

through their oral health behaviour and gingival

health. There may be different mechanisms for causal

models in boys and girls. School children as a whole

who consciously try to maintain good oral health,

then, do in fact practice good health behaviours.

Some modifications to our initial model were suggested from the Amos programme [21]. For example, the path from childrens grade to their oral

health behaviour was added as it was theoretically

plausible to consider that childrens educational

level might explain and influence their brushing

behaviour. In the current study, childrens grade was

negatively linked to their oral health behaviour, the

opposite to what was expected. This path was necessary to provide a good fit to the data. One possible

reason for finding a negative path from grade to oral

health behaviour might be that some children have

not brushed and flossed their teeth willingly. For

most Japanese mothers, the extent to which they

check up on their childrens teeth and oral hygiene

gradually decreases until the child starts elementary

school [22]. Another reason might be that dentists

generally treat their patients when they have dental

pain and have not encouraged their patients brushing and flossing, although behavioural management

is considered as the treatment of choice [23].

2002 BSPD and IAPD, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12: 101108

IPD_338.fm Page 106 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

106

M. Okada et al.

There are limitations in the methods and results of

this study. First, parents educational level and social

class were not accounted for in the model. Eccleston

[24] wrote, however, In Japan there are less significant social or class divisions. There is believed to

be less socio-economic variation in Japanese culture

than in other countries. Approximately 95% of people

go to senior high school and most people would be

described as coming from middle class backgrounds.

All people in Japan are covered under medical and

dental insurance. Questions such as personal finance

or educational level are considered sensitive issues

to Japanese people; including such questions would

be likely to reduce the participation rate dramatically. Also, items with regard to fluoride were not

included. One of the reasons was that the items on

fluoride seemed to have a problem of face validity

in Japan: fluoride application has so far reached only

a small percentage of the Japanese population [25]

and people appeared less well-informed on the benefits of water fluoridation [26].

Secondly, the participation rate of the present

study was not high. Parents having negative attitudes

toward oral health care would be unlikely to have

responded to the questionnaire. Therefore, the real

state of parentchild relations may differ to some

extent from that shown in the model. Thirdly, the

internal reliability of the OHB-C was not adequate

to assess childrens oral health behaviour. Further

research is needed to examine and develop its metric

properties of reliability and validity. Fourthly, it might

be better to investigate the influences of fathers and

mothers oral health behaviour separately. When the

data for 256 mothers were analysed, the causal relationship was almost the same as that in Fig. 2

(results not shown). This study, however, was not

intended to clarify differences in parental background. It is common in Japan for mothers with

school-age children not to work outside the home.

Ozawa [27] reported that Japans labour market is

still shaped by the uniform assumption that men go

outside to work while women maintain the home.

The mother to father ratio in the participants may

reflect these circumstances. Fifthly, in cross-sectional

studies, the causal interpretation of LISREL (like

any other multivariate statistical method) is fundamentally incorrect. Prospective, longitudinal research

employing causal modelling techniques might be

needed to clarify the nature of these relationships.

Despite the above-mentioned shortcomings of this

study, it can be seen that gingival health status of

school children and their parents oral health behaviour have significant direct relationships with the

childrens dental caries. Parents oral health behaviour could influence their childrens gingival health

and dental caries directly, or indirectly through its

effect on childrens oral health behaviour, although

differences in cultural background and education

between countries may have contributed to the trend

seen in the results of this study.

Rsum. Objectifs. Cette tude a eu pour objectif

dexaminer les interrelations simultans entre

lhygine buccale des parents et ltat de sant

buccale de leur enfant scolaris.

Mthodes. Sujets comprenant 296 paires parents

(pre ou mre) et leurs enfants dans une cole

lmentaire de Hiroshima. Lexamen dentaire de

lenfant a t ralis laide des critres diagnostiques de carie de lOrganisation Mondiale de la

Sant (OMS) pour les dents caries (DT) et obtures

(FT). Lindice dvaluation buccal pour les enfants

(ORI-C) a t utilis pour lexamen de la sant

gingivale des enfants. Le HU-DBI (Evaluation de

comportement dentaire de lUniversit de Hiroshima)

a t utilis pour valuer les habitudes dhygine

buccale des parents. Un modle comportemental

parent-enfant a t test par le programme LISREL

(relations structurelles linaires).

Rsultats. Il y avait une corrlation significative

entre DT et ORI-C (r = 0,168; p < 0,01). Une corrlation a t retrouve entre ORI-C et les habitudes

de sant buccale des enfants (OHB-C) (OHB-C)

(r = 0,182; p < 0,01). OHB-C tait significativement

associ HU-DBI (r = 0,251; p < 0,001). Le modle

suppos aprs quelques rvisions tait reliable aux

donnes data (2 = 1,3, df = 6, p = 0,97; Indice

dadquation = 0,999). Les habitudes de sant

buccale des parents avaient galement un effet direct

sur les habitudes de sant buccale des enfants

( p < 0,001). Les habitudes de sant buccale des

enfants affectaient leurs DT par leur effet sur ltat

de sant gingivale. Les habitudes de sant buccale

des parents avaient aussi un effet significatif direct

sur les DT de leurs enfants ( p < 0,05). Les habitudes

de sant buccale des parents affectaient les habitudes de sant buccale de leurs enfants ( p < 0,001).

Le grade des enfants affectait la fois le DT et leurs

habitudes de sant buccale.

Conclusions. Les habitudes de sant buccale des

parents pourraient avoir une influence directe sur la

sant gingivale et les caries de leurs enfants et/ou

2002 BSPD and IAPD, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12: 101108

IPD_338.fm Page 107 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

Parents influence childrens oral health

indirecte travers leurs effets sur les habitudes de

sant buccale de ceux-ci.

Zusammenfassung. Ziele. Untersuchung der Wechselbeziehung zwischen elterlichem Mundgesundheitsverhalten und dem Mundgesundheitszustand

des Kindes.

Methoden. Die Stichprobe umfasste 296 Elternpaare

(Mutter oder Vater) und deren Kinder an einer

Grundschule in Hiroshima. Die Untersuchung der

Kinder erfolgte nach WHO-Kriterien aufgeschlsselt

in karise Zhne (DT) und Zhne mit Restaurationen

(FT). Der Oral Rating Index fr Kinder (ORI-C)

wurde zur Untersuchung der Gingiva herangezogen.

Das Hiroshima Universitt Dental Behaviour Inventory (HU-DBI) wurde benutzt zur Feststellung des

Mundgesundheitsverhaltens der Eltern.

Eine Eltern-Kind-Verhaltensmodell wurde mit dem

LISREL Programm getestet.

Ergebnisse. Es zeigte sich eine signifikante Korrelation zwischen DT und ORI-C (r = 0.168; p < 0.01)

und zwischen ORI-C und OHB-C (r = 0.182; p < 0.01)

sowie zwischen OHB-C und HU-DBI (r = 0.251;

p < 0.001). Das angenommene Modell war nach

einigen nderungen vereinbar mit den Daten (2 = 1.3,

df = 6, p = 0.97; Goodness of Fit Index = 0.999).

Das Mundgesundheitsverhalten der Eltern beeinflusste das Mundgesundheitsverhalten der Kinder

( p < 0.001). Das Mundgesundheitsverhalten der

Kinder beeinflusste den DT-Wert durch den Effekt

auf die Gingiva. Das Mundgesundheitsverhalten der

Eltern hatte einen signifikanten direkten Einfluss auf

den DT-Wert ihrer Kinder ( p < 0.05). Die Klassenstufe beeinflusste sowohl DT als auch das Mundgesundheitsverhalten der Kinder.

Schlussfolgerungen. Das elterliche Mundgesundheitsverhalten knnte die Gingivagesundheit sowie

Kariesentstehung direkt beeinflussen oder indirekt

ber das Mundgesundheitsverhalten der Kinder.

Resumen. Objetivo. El objetivo de este estudio fue

el de examinar las relaciones simultneas entre las

conductas sobre la higiene oral de los padres y el

estado de salud oral de sus hijos/as en edad escolar.

Mtodos. Los sujetos comprendan 296 parejas de

padres (madre o padre) y sus hijos en una escuela

elemental de Hiroshima. El examen dental de los

nios se realiz usando el criterio diagnstico de

caries de la Organizacin Mundial de la Salud

(OMS) para dientes cariados (DC) y dientes obturados (DO). Se utiliz el Indice de valoracin oral

107

para nios (ORI-C) para examinar la salud gingival.

Se utiliz el Inventario de conducta oral de la Universidad de Hiroshima (HU-DBI) para analizar las

conductas sobre salud oral de los padres. Se prob

un modelo de comportamiento padre-hijo a travs

del programa de las relaciones lineales estructurales

(LISREL).

Resultados. Exista una correlacin significativa

entre DC y ORI-C (r = 0,168; p < 0,01) Se encontr

correlacin entre ORI-C y Comportamiento sobre

higiene oral en los nios (OHB-C) (r = 0,182;

p < 0,01) El OHB-C se asoci significativamente

con el HU-DBI (r = 0,251; p < 0,001)

El modelo hipottico, prob ser consistente con

los datos, despus de algunas revisiones (2 = 1,3;

do = 6; p = 0,97; Indice de Bienestar = 0,999) La

conducta sobre la salud oral de los padres afectaba

la conducta sobre la salud oral de sus hijos

( p < 0,001). La conducta sobre salud oral de los nios

afectaba su DO y tambin a los niveles de salud

gingival. Las conductas de salud oral de los padres

tambin tenan un efecto directo sobre el DO de sus

hijos ( p = 0,05). El grado de los nios afectaba tanto

a su DO como a su conducta de higiene oral.

Conclusiones. La conducta sobre la higiene oral de

los padres puede influir en la salud gingival y caries

dental de sus hijos directa o indirectamente a travs

de sus efectos en la conducta de higiene oral de sus

hijos.

References

1 Blinkhorn AS. Dental preventive advice for pregnant and

nursing mothers sociological implications. International

Dental Journal 1981; 31: 14 22.

2 Sasahara H, Kawamura M, Kawabata K, Iwamoto Y. Relationship between mothers gingival condition and caries

experience of their 3-year-old children. International Journal

of Paediatric Dentistry 1998; 8: 261267.

3 Sarnat H, Kagan A, Raviv A. The relation between mothers

attitude toward dentistry and the oral status of their children.

Pediatric Dentistry 1984; 6: 128 131.

4 Chang C, Chen LH, Chen PY. Developmental stages of Chinese childrens concepts of health and illness in Taiwan.

Chung Hua Min Kuo Hsiao Erh Ko I Hsueh Hui Tsa Chih

1994; 35: 2735.

5 Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: a

Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey:

Prentice Hall, 1986.

6 Blinkhorn AS. Influence of social norms on toothbrushing

behavior of preschool children. Community Dentistry and

Oral Epidemiology 1978; 6: 222 226.

7 Jreskog KG. Structural analysis of covariance and correlation matrices. Psychometrika 1978; 43: 443477.

8 Sallis JF, Nader PH. Family determinants of health behaviors.

2002 BSPD and IAPD, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12: 101108

IPD_338.fm Page 108 Tuesday, March 12, 2002 6:23 PM

108

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

M. Okada et al.

In: Gochman DS (ed.). Health Behavior. Emerging Research

Perspectives. New York: Plenum Press, 1988: 107126.

strom AN, Jakobsen R. The effect of parental dental health

behavior on that of their adolescent offspring. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 1996; 54: 235 241.

Stewart JE, Jacobs-Schoen M, Padilla MR, Maeder LA, Wolfe

GR, Harts GW. The effect of a cognitive behavioral intervention on oral hygiene. Journal of Clinical Periodontology

1991; 18: 219222.

McCaul KD, Glasgow RE, Gustafson C. Predicting levels of

preventive dental behaviors. Journal of the American Dental

Association 1985; 111: 601605.

Tedesco LA, Keffer MA, Fleck-Kandath C. Self-efficacy,

reasoned action, and oral health behavior reports: a social

cognitive approach to compliance. Journal of Behavioral

Medicine 1991; 14: 341355.

Okada M, Kuwahara S, Kaihara Y et al. Relationship between

gingival health condition and dental caries in children aged

712 years. Journal of Oral Science 2000; 42: 151155.

Kawamura M, Iwamoto Y, Wright FAC. A comparison of

self-reported dental health attitudes and behavior between

selected Japanese and Australian students. Journal of Dental

Education 1997; 61: 354360.

Kawamura M. Dental behavioral science The relationship

between perceptions of oral health and oral status in adults

[in Japanese]. Journal of Hiroshima University Dental Society

1988; 20: 273286.

Kawabata K, Kawamura M, Miyagi M, Aoyama H, Iwamoto

Y. The dental health behavior of university students and testretest reliability of the HU-DBI [in Japanese]. Journal of

Dental Health 1990; 40: 474 475.

Okada M, Kuwahara S, Kozai K, Kawamura M, Nagasaka N.

The efficacy of an oral rating index for children for screening

gingival health and oral hygiene status. Pediatric Dental Journal 1999; 9: 9197.

18 World Health Organization. Individual tooth status and treatment need. In: Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods, 3rd edn.

Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987: 3439.

19 Fukai K, Maki Y, Takaesu Y. Oral health behavior of adults

in relation to age groups [in Japanese, English abstract]. Journal of Dental Health 1996; 46: 676682.

20 Kawamura M, Iwamoto Y. Present state of dental health

knowledge, attitudes/ behaviour and perceived oral health of

Japanese employees. International Dental Journal 1999; 49:

173 181.

21 Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 40 Users Guide. Chicago:

SmallWaters, 1999.

22 Taura K. Relationship between dental caries in deciduous

teeth and tooth brushing in nursery school children [in

Japanese, English abstract]. Journal of Dental Health 1981;

31: 2 16.

23 Kawamura M, Sasaki T, Imai-Tanaka T, Yamasaki Y,

Iwamoto Y. Service-mix in general dental practice in Japan:

a survey in a suburban area. Australian Dental Journal 1998;

43: 410 416.

24 Eccleston B. Social equality: the distribution of income and

wealth. In: State and Society in Post-War Japan. Oxford:

Blackwell Publishing, 1993: 164167.

25 Kobayashi S, Kawasaki K, Takagi O et al. Caries experience

in subjects 18 22 years of age after 13 years discontinued

water fluoridation in Okinawa. Community Dentistry and Oral

Epidemiology 1992; 20: 81 83.

26 Tsurumoto A, Wright FAC, Kitamura T, Fukushima M,

Campain AC, Morgan MV. Cross-cultural comparison of

attitudes and opinions on fluorides and fluoridation between

Australia and Japan. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 1998; 26: 182 193.

27 Ozawa I. Increasing choices for women. In: Blueprint for a

New Japan. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1994: 192

194.

2002 BSPD and IAPD, International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 12: 101108

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Welcome To MEGA PDFDokument9 SeitenWelcome To MEGA PDFRüdiger TischbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Even More ScaredDokument108 SeitenEven More ScaredManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- SdarticleDokument3 SeitenSdarticleManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Titanium Framework Removable Partial Denture Used ForDokument4 SeitenTitanium Framework Removable Partial Denture Used ForManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Oral HealthDokument7 SeitenChild Oral HealthManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijms 23 01049Dokument14 SeitenIjms 23 01049Manjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypersensitivity To Temporary Soft Denture LinersDokument3 SeitenHypersensitivity To Temporary Soft Denture LinersManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sdarticle PDFDokument2 SeitenSdarticle PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sdarticle PDFDokument8 SeitenSdarticle PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sdarticle PDFDokument4 SeitenSdarticle PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sdarticle PDFDokument9 SeitenSdarticle PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sdarticle PDFDokument10 SeitenSdarticle PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reliability, Validity, and Utility of Various Occlusal Measurement Methods and TechniquesDokument7 SeitenReliability, Validity, and Utility of Various Occlusal Measurement Methods and TechniquesManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Luzerne Jordan, Washington, D. CDokument2 SeitenLuzerne Jordan, Washington, D. CManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 PDFDokument6 Seiten12 PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sdarticle PDFDokument3 SeitenSdarticle PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Luzerne Jordan, Washington, D. CDokument2 SeitenLuzerne Jordan, Washington, D. CManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 PDFDokument6 Seiten9 PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5Dokument9 Seiten5Manjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 PDFDokument13 Seiten8 PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 PDFDokument9 Seiten10 PDFManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- President'S Address: Detroit, MichDokument2 SeitenPresident'S Address: Detroit, MichManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joel Friedman, Brooklyn, N. Y.: Received 82Dokument5 SeitenJoel Friedman, Brooklyn, N. Y.: Received 82Manjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- President'S Address: Detroit, MichDokument2 SeitenPresident'S Address: Detroit, MichManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5Dokument9 Seiten5Manjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dcpavtmelzt of Prosthetics, Ivrrrthsarstcrn Unioersity Dental School, Chicago, 111Dokument3 SeitenDcpavtmelzt of Prosthetics, Ivrrrthsarstcrn Unioersity Dental School, Chicago, 111Manjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abraham E-I. Lazarus,: New York, N. IDokument5 SeitenAbraham E-I. Lazarus,: New York, N. IManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- DisclaimerDokument2 SeitenDisclaimerManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilfrid Hall Terrell, Calif.: ExaminationDokument25 SeitenWilfrid Hall Terrell, Calif.: ExaminationManjeev GuragainNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Indigenous Women and FeminismDokument27 SeitenIndigenous Women and FeminismClaudia ArteagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mgt503 Latest Mcqs Covering Lectures 1 40Dokument79 SeitenMgt503 Latest Mcqs Covering Lectures 1 40prthr100% (1)

- Goethe Elective Affinities TextDokument4 SeitenGoethe Elective Affinities TextAaronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freedom of SpeechDokument13 SeitenFreedom of SpeechNicolauNoch keine Bewertungen

- ProspectingDokument21 SeitenProspectingCosmina Andreea ManeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essential RightDokument42 SeitenEssential Righthamada3747Noch keine Bewertungen

- Semester ReflectionDokument5 SeitenSemester Reflectionapi-316647584Noch keine Bewertungen

- BaZi Basico PDFDokument54 SeitenBaZi Basico PDFMelnicof DanyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service Marketing Final 29102012Dokument73 SeitenService Marketing Final 29102012Prateek Maheshwari100% (1)

- Ethical Decision Making and Ethical LeadershipDokument11 SeitenEthical Decision Making and Ethical LeadershipmisonotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studies in Applied Philosophy, Epistemology and Rational EthicsDokument291 SeitenStudies in Applied Philosophy, Epistemology and Rational EthicsRey Jerly Duran BenitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ConjunctionDokument2 SeitenConjunctionAngelo Cobacha100% (1)

- He History of ArticulatorsDokument13 SeitenHe History of ArticulatorsrekabiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fce Speaking Test ChecklistDokument2 SeitenFce Speaking Test Checklist冰泉100% (1)

- AUI4861 Assignment 02 Byron Jason 46433597Dokument18 SeitenAUI4861 Assignment 02 Byron Jason 46433597Byron Jason100% (2)

- Ref Phy 9Dokument1.351 SeitenRef Phy 9mkumar0% (2)

- BRMM 575 Chapter 2Dokument5 SeitenBRMM 575 Chapter 2Moni TafechNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jaimini KarakasDokument3 SeitenJaimini KarakasnmremalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trustworthiness and Integrity in Qualitative ResearchDokument25 SeitenTrustworthiness and Integrity in Qualitative ResearchcrossNoch keine Bewertungen

- Category Total Views: 822 This Poetry Has Been Rated 0 Times Rate This PoemDokument2 SeitenCategory Total Views: 822 This Poetry Has Been Rated 0 Times Rate This PoemrajikrajanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Principles in 3D AnimationDokument4 Seiten12 Principles in 3D AnimationfurrypdfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Connections and SymbolsDokument253 SeitenConnections and SymbolsMarko CetrovivcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Darkside Hypnosis - October Man PDFDokument17 SeitenDarkside Hypnosis - October Man PDFManuel Herrera100% (3)

- Upload.c Uhse002 3n12Dokument22 SeitenUpload.c Uhse002 3n12رمزي العونيNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 21 - 30Dokument48 SeitenLesson 21 - 30Rizuanul Arefin EmonNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of ChemistryDokument10 SeitenHistory of ChemistryThamil AnbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- DuBois, The Pan-Africanist and The Development of African Nationalism - Brandon KendhammerDokument22 SeitenDuBois, The Pan-Africanist and The Development of African Nationalism - Brandon KendhammerElmano MadailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2013 Multivariate Statistical Analysis IDokument36 SeitenChapter 2013 Multivariate Statistical Analysis IShiera Mae Labial LangeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kindergarten Science Lesson WormsDokument3 SeitenKindergarten Science Lesson Wormsapi-402679147Noch keine Bewertungen

- GCWORLD Concept MapDokument1 SeiteGCWORLD Concept MapMoses Gabriel ValledorNoch keine Bewertungen