Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Agroecosistema, Conservation Biology

Hochgeladen von

Camila Antonia Prado RecabarrenCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Agroecosistema, Conservation Biology

Hochgeladen von

Camila Antonia Prado RecabarrenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Editorial

The Agroecosystem: A Need for the Conservation

Biologists Lens

The alarm bells signaling the loss of biodiversity ring

loud and clear throughout most of the world. Yet the

precise tones of those bells are elusive, with various receptors tuned to receive particular frequencies, filtering

out the rest as if it were so much confusing cacophony.

One can become schizophrenic if one changes the dial

on that tuner and listens in on the receivers of alternative discourses. We are thinking of two of the most ardent proponents of biodiversity preservation, conservation biologists and agroecologists. Practitioners in both

these fields lose no opportunity to lament the passing of

biodiversity. Both regard that passing as somewhere between serious and catastrophic. Both clamor for political

and technical action to stop the losses. Yet the discourses of the two are surprisingly different, leading to

different emphases on strategies for both political persuasion and technical research. We suggest that this dichotomy is unfortunate and unnecessary and that the

time is ripe to combine forces. Such a combination

could have positive benefits, both in generating and clarifying needed lines of research and in pointing to concrete actions to stem the current rip tide of biodiversity

loss on the planet.

The arguments of the conservation biologists are not

unfamiliar to the readers of this journal. Species are all

rivetswhen the key one falls out our plane falls down;

the rain forest carries the cure for cancer and AIDS; rain

forest fruits will solve rural poverty; we lose a bit of our

own humanity as we lose our distant relatives. Whatever

the favored argument, they all point in the same direction: the extinction of biological types is something to

be concerned, even panicked, about. This general discourse has led to a research agenda that includes assessment of biodiversity and its loss in various ecosystems,

study of genetic background for the likelihood of extinctions, study of various ecological mechanisms of maintaining biodiversity, particular autecological concerns

with ones favorite charismatic megafauna, etc.

The foci of agroecologists are fundamentally different,

originating probably from more short-term practical concerns. The postWorld War II triumph of monocultures

based on petroleum pesticides brought with it an inevi-

table loss of biodiversity. This is one ecosystem in which

one of the main goals of ecosystem managers, at least in

the past, has been to purposefully reduce biodiversity as

much as possible. From the massive genetic diversity of

traditional agroecosystems, we now have thousands of

hectares planted with the same hybrid corn variety.

From the rich soil flora and fauna, the workings of

which are still mainly enigmatic, we have reduced many

soils to almost nothing more than hydroponic media, as

devoid of life as possible. From the rich assemblage of

parasitic and predatory arthropods that kept herbivores

at non-pest levels in earlier days, we now have only a

threesomethe plant, the pest, and the agent of control, the latter usually a pesticide made from petroleum.

Participants in the world-wide movement toward sustainable agricultural systems recognize biodiversity as

somehow important to the future sustainability of these

ecosystems and lament its loss as much as any conservation biologist (Perfecto et al. 1996, 1997; Vandermeer

1996). Yet the concerns are far more practical. What

part of the biodiversity does or could function in specific ways to promote the sustainability of future systems? Are particular species groups functionally redundant? Does a multiple cropping system allow for better

pest control? Such questions form the discourse of agroecologists, a discourse that has led to a research agenda

that includes study of the specific function of various

subgroups, the specific role of individual species or genotypes in production or risk reduction, the productive advantages of multiple cropping systems, and the functional redundancy of particular groups, etc.

Conservation biologists have been mainly concerned

with the origin and maintenance of biodiversity, whereas

agroecologists have been mainly concerned with its

function. The former are concerned with so-called natural

systems and leaving them alone, whereas the latter are

concerned with managed systems and managing them

better. Certainly there is overlap, yet the general atmosphere in which biodiversity questions are formulated

and debated could not be more differentas if one is

dropping an empty coke bottle on the others Kalahari.

Consider, for example, our recent work on arthropod

591

Conservation Biology, Pages 591592

Volume 11, No. 3, June 1997

592

Editorial

biodiversity and its loss in agroecosystem transformation

(Perfecto 1996, 1997). To our surprise we discovered an

enormous biodiversity of Coleoptera, Formicidae, and

microhymenoptera in traditional coffee agroecosystems,

and a dramatic loss in all those groups as the modernization and technification of that system proceeded. It

is a result that would seem of particular interest to both

conservation biologists and agroecologists. Yet both

communities have demonstrated little interest. One famous conservation biologist once publicly dismissed

such studies because there are no endangered species

in agroecosystems, and in general managed systems are

somehow less legitimate for conservation work and

conservation biology research. We hope that the recent

discovery of the Pink-legged Graveteiro in traditional cacao agroecosystems in Brazil (Line 1996) will act as a

wake-up call. At the other extreme, agroecologists also

show scant interest in these studies because we are simply talking about biodiversity and not about its function

in the production of the system. The fact that hundreds

of species of beetles will disappear from an area if traditional coffee production is replaced with technified production is not generally of interest, unless it can be

shown that those hundreds of species also include a

predator of the coffee berry borer or some other pest.

Conservation biologists seem not to be concerned because the systems are already tainted. Agroecologists

seem not to be concerned because biodiversity in and of

itself has no obvious connection to production.

This division is unfortunate. The fact is that most of

the terrestrial world is, in one sense or another, an agroecosystem. If we are to ignore this ecosystem simply because it does not fall within our romantic notion of

pristineness, we leave the vast majority of the Earths

surface to the husbandry of those who care little about

biodiversity preservation. On the other hand, if we are

to ignore the preservation of biodiversity per se simply

because it does not fit obviously into classical production categories, we leave the preservation of the worlds

biodiversity to those who refuse to work outside of national parks and nature preserves.

Recently there has been considerable interest in the

coffee agroecosystem in Central America, spawned

partly by the realization that migrant birds use this habitat during the winter (Greenberg et al. 1997). This example should provide us with an object lesson. Little interest on the part of conservationists was displayed until

the connection with bird diversity became known. Now

Conservation Biology

Volume 11, No. 3, June 1997

it is too late. Much of Central America has already been

converted, and the political momentum for conversion

will be very hard to overcome. Had conservation biologists been concerned with this ecosystem 20 years ago,

perhaps our knowledge about its basic ecology and the

role of biodiversity therein would be better than it is

now, enabling us to make recommendations for agroecosystem design that would support biodiversity. Furthermore, had there been conservation interest in this ecosystem 20 years ago, the dramatic push to make farmers

transform their methods (even those who didnt want

to) may have been less successful.

There still exist many biodiversity-rich agroecosystems, especially in tropical areas, and part of the movement toward sustainable agriculture has as a central goal

the generation and maintenance of biodiversity. If the

conservation biology community would begin thinking

of agroecosystems as legitimate objects of study and begin asking the same questions about agroecosystems

they ask of natural systems, the topic of biodiversity in

the movement toward sustainable agriculture could be

better understood, and thus better managed, leading to

better preservation. Andwho knowswe might prevent some species from becoming endangered.

John Vandermeer

Department of Ecological Agriculture, Wageningen Agricultural University,

Haarweg 333, NL-6709 RZ Wageningen, The Netherlands, email jvander@

umich.edu

Ivette Perfecto

Department of Entomology, Wageningen Agricultural University, The

Netherlands

Literature Cited

Greenberg, R., P. Bichier, and J. Sterling. 1997. Bird populations and

planted shade coffee plantations of eastern Chiapas. Biotropica. In

Press.

Line, L. 1996. Brazils dwindling cocoa crop may put newly discovered

bird at risk. New York Times, 19 November: B6, C4.

Perfecto, I., J. Vandermeer, P. Hanson, and V. Cartin. 1997. Arthropod

biodiversity loss and the transformation of a tropical agro-ecosystem. Biodiversity and Conservation. In Press.

Perfecto, I., R. A. Rice, R. Greenberg, and M. E. Van der Voort. 1996.

Shade coffee: a disappearing refuge for biodiversity. BioScience 46:

598608.

Vandermeer, J. H. 1996. Biodiversity loss in and around agroecosystems. Pages 111127 in J. Rosenthal, editor. Biodiversity and human health.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Technical SafetyDokument4 SeitenTechnical SafetyTayo TinuoyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Design and Fabrication of Agitated Thin Film Dryer": Bhushan M. Thengre, Sulas G. BorkarDokument11 Seiten"Design and Fabrication of Agitated Thin Film Dryer": Bhushan M. Thengre, Sulas G. BorkarshirinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brochure IndowaterDokument6 SeitenBrochure IndowateraryoNoch keine Bewertungen

- (En GB) DBE 821 - 1.00Dokument7 Seiten(En GB) DBE 821 - 1.00Enio Miguel Cano LimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AQUABREAK PX English PDFDokument4 SeitenAQUABREAK PX English PDFMilan ChaddhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quick Study On Waste Management in Myanmar: DraftDokument23 SeitenQuick Study On Waste Management in Myanmar: DraftRicco ChettNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Economics of RecyclingDokument5 SeitenThe Economics of RecyclingNazrin VahidovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHINA DOESN'T CONTROL HFCs (GHG) EMISSIONS (-ECFI Exercise-)Dokument3 SeitenCHINA DOESN'T CONTROL HFCs (GHG) EMISSIONS (-ECFI Exercise-)Juan Daniel Mayta SoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Makalah Bhs InggrisDokument8 SeitenMakalah Bhs InggrismarasabessiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Achieving Zero Waste-A Study of Successful Diversion of Convention-Generated Waste in Key West, FloridaDokument5 SeitenAchieving Zero Waste-A Study of Successful Diversion of Convention-Generated Waste in Key West, FloridaRezaul Karim TutulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lubrico Titanium C5 Hoja TecnicaDokument1 SeiteLubrico Titanium C5 Hoja TecnicaRJ Josmel RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Simplified Simulation Model of RO Systems For Seawater DesalinationDokument12 SeitenA Simplified Simulation Model of RO Systems For Seawater DesalinationHarold Fernando Guavita ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSTP 2 Project ProposalDokument6 SeitenNSTP 2 Project ProposalJayc Chantengco100% (1)

- MSDS ShellCompressorOilDokument14 SeitenMSDS ShellCompressorOilSurendran NagiahNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSDS Bilirubin TotalDokument3 SeitenMSDS Bilirubin TotalRina suzantyNoch keine Bewertungen

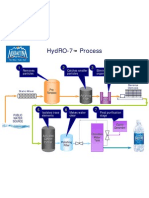

- Aqua Fin A Purification DiagramDokument1 SeiteAqua Fin A Purification DiagramPEPITOPULNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contoh Teks Bahasa Inggris Tentang Recycling - Asymmetrical LifeDokument9 SeitenContoh Teks Bahasa Inggris Tentang Recycling - Asymmetrical Lifehenry tantyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stabilization and SolidificationDokument37 SeitenStabilization and SolidificationHY YeohNoch keine Bewertungen

- H.H.E Ydraulique Et Ydrologie Nvironnementale: G.C 3 Lecturer: Mr. J.RammaDokument31 SeitenH.H.E Ydraulique Et Ydrologie Nvironnementale: G.C 3 Lecturer: Mr. J.RammaAnoopAujayebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Omission Addition SR No. Description BOQ Ref. Unit Quantity Rate (AED) Amount (AED) RemarksDokument1 SeiteOmission Addition SR No. Description BOQ Ref. Unit Quantity Rate (AED) Amount (AED) Remarkslayaljamal2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kingspan Isophenic Paneli PrezentacijaDokument2 SeitenKingspan Isophenic Paneli PrezentacijataskesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Floods in BangladeshDokument8 SeitenFloods in BangladeshGopal Saha KoushikNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3M Novec 1230 Fluid Protect What Matters BrochureDokument4 Seiten3M Novec 1230 Fluid Protect What Matters BrochureMichael LagundinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Supply Engineering PracticalDokument5 SeitenWater Supply Engineering PracticalJust for FunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cloze TestDokument3 SeitenCloze TestNguyen Thanh NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- EnvironmentDokument17 SeitenEnvironmentNiza FuentesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cobetter BGPP160 FilterDokument1 SeiteCobetter BGPP160 FilterVictor LiangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Standard - Code of Basic Requirements For Water Supply, Drainage and Sanitation (Fourth Revision)Dokument20 SeitenIndian Standard - Code of Basic Requirements For Water Supply, Drainage and Sanitation (Fourth Revision)vipul sachanNoch keine Bewertungen

- UPI Product-CatalgueDokument13 SeitenUPI Product-Catalguenour eldinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Contoso CorporationDokument12 SeitenThe Contoso CorporationKe LiNoch keine Bewertungen