Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ojpm 2014011014354742

Hochgeladen von

Tuti AlawiyahOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ojpm 2014011014354742

Hochgeladen von

Tuti AlawiyahCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Vol.4, No.

1, 8-12 (2014)

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2014.41002

Open Journal of Preventive Medicine

Racial disparity in years of potential life lost to

induced abortions

James Studnicki1*, Sharon J. MacKinnon2, John W. Fisher1

1

Department of Public Health Sciences, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, USA;

Corresponding Author: jstudnic@uncc.edu

2

Doctoral Program in Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, USA

*

Received 31 October 2013; revised 3 December 2013; accepted 21 December 2013

Copyright 2014 James Studnicki et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License,

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual

property James Studnicki et al. All Copyright 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

ABSTRACT

The magnitude of the overall prevalence and

racial disparity in induced abortion suggests

that it is a major influence on the demographic

and socioeconomic composition of the population of the United States (US). However, the years

of potential lives averted by induced abortion

have not been systematically studied. We applied race-specific intra-uterine death estimates

to the induced abortions occurring to non-Hispanic (NH) white and non-Hispanic (NH) black

women in the US state of North Carolina in 2008.

The resultant estimate of births averted by induced abortion was used to project years of potential life lost. All-cause detailed mortality data

were used to compare induced abortion with

other contributing causes of years of potential

life lost before age 75 (YPLL 75). For NH whites,

induced abortions in 2008 contributed 59% of

total YPLL 75, and 1.5 times the total YPLL 75

from all other causes combined. For NH blacks,

induced abortions in 2008 contributed 76% of

total YPLL 75 and 3.2 times the total YPLL 75

from all other causes combined. Induced abortion is the overwhelmingly predominant contributing cause of preventable potential lives lost

in the North Carolina population, and NH blacks

are disproportionately affected.

KEYWORDS

Abortion; Years of Potential Life Lost

1. INTRODUCTION

Large racial differences have been consistently obCopyright 2014 SciRes.

served for a number of years in pregnancy rates, average

lifetime pregnancies and induced abortion rates [1-3].

Based on the most recent multi-year national summary of

pregnancy outcomes, covering the years 1990-2008, in

2008 in the US, 64.6% of all pregnancies ended in a live

birth, 17% in an intrauterine death (includes miscarriages

occurring at less than 20 weeks and stillbirths >20 weeks

gestation), and 18.4% in an induced abortion [3]. The

overall (all maternal ages) pregnancy rate for NH black

women was 144.3 per 1000, 65% higher than the rate for

NH white women (87.5 per 1000 women). According to

the same report, NH black women experience an average

of more pregnancies in a lifetime (4.3) than NH white

women (2.7). In 2008, 69% of NH white but only 49% of

NH black pregnancies resulted in a live birth [3]. For NH

white women 12.4% of pregnancies were terminated by

induced abortions, whereas the percentage for NH black

women was nearly three times higher at 35.6% [3]. There

were 5.5 NH white live births for every NH white induced abortion, but only 1.4 NH black live births for

every NH black induced abortion. Therefore, in spite of a

higher pregnancy rate than NH whites, pregnancies experienced by NH black women are much less likely to

result in a live birth, largely as the result of their dramatically higher induced abortion rate. The abortion experience of Hispanic women closely corresponds to that of

NH whites and was therefore not included in this analysis [3].

Both the magnitude of the prevalence of induced abortion and the huge NH black/NH white racial disparity

suggest that it is a major influence on the demographic,

socioeconomic and cultural composition of the United

States population. An understudied aspect of particular

interest in this regard is the estimate of the years of potential lives averted by induced abortions. The statistical

construct of Years of Potential Life Lost (YPLL) is the

OPEN ACCESS

J. Studnicki et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 4 (2014) 8-12

most widely applied method of characterizing the burden

of premature death within defined populations. It has

been included by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) in its standard reports since 1982 [4]

and extensively applied in measuring and comparing the

health status of cities [5], counties [6] and states [7]

within the US, as well as in comparisons of nations conducted by international organizations [8]. The YPLL

method, however, has not previously been used to characterize the burden of potential lives lost to induced

abortion. It is of interest to note that previous YPLL analyses have included infant mortality and perinatal conditions as causes of death, even though the latter includes

conditions arising between 28 weeks of gestation and 7

days of life [9]. In those applications of YPLL, the qualifying condition for inclusion as a potential life lost,

therefore, has been that there must be a live birth and not

merely some minimum defined gestational period. This

same reporting convention regarding the nature of potential life lost can be seen in the inconsistency surrounding

the counting of stillbirth (intrauterine death occurring in

the third trimester) as a death. One observer has questioned why the 35 week old neonate who dies of respiratory failure 24 hours after delivery and the developmentally indistinguishable 35 week old stillborn baby are

treated differentially in mortality statistics; i.e., one is

considered as a death, and therefore as a potential life

lost, while the other is not [10]. The likely explanation,

of course, is that attributing existing (or potential) life to

an intrauterine loss due to natural means (i.e. spontaneous abortion) by counting it as a death (or potential life)

could suggest equivalent treatment of elective abortions.

However, requiring that only a live birth can represent

years of potential life lost is a logical tautology for induced abortion, the specific intent of which is to prevent

a live birth.

The rationale for the use of a confirmed pregnancy rather than a live birth as a measure of potential life lost by

means of induced abortions is logically persuasive and

empirically validated. Potential lives lost to induced

abortion can be accurately estimated from confirmed

pregnancies because: 1) in the absence of induced abortion, physiological factors are the sole determinants of

whether conception actually results in a live birth [11], 2)

induced abortion averts both live births and intra-uterine

deaths so not all aborted fetuses would result in a live

birth in the absence of induced abortion; 3) Intra-uterine

deaths at all gestational stages following a confirmed

pregnancy are reasonably estimated on the basis of empirical studies of pregnant populations as well as extensive surveys of women who have experienced miscarriages and stillbirths, thus enabling an accurate estimate

of potential lives lost to induced abortions [12]. Further,

the reluctance to quantify the measurable impact of inCopyright 2014 SciRes.

duced abortion impedes legitimate discourse regarding

its societal consequences. Therefore the objective of this

research was to apply the concept of YPLL to induced

abortion within a geographically defined population of

NH blacks and NH whites; and, to compare the magnitude of its impact against other causes of potential life

lost.

2. METHOD

2.1. Data

Event-level and aggregated data used in this analysis

were all de-identified and publically available from the

following sources: The North Carolina State Center for

Health Statistics (NC-SCHS) provided pregnancy counts

for North Carolina residents by year (2008), county,

mothers race and Hispanic origin, age, education and

marital status. Reported pregnancies include live births,

induced abortions and fetal deaths of 20 or more weeks

of gestation. Detailed event-level mortality statistics provided death counts for North Carolina residents by year

(2008), cause of death, county, race, gender, age and

Hispanic origin. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) provided estimated national pregnancy rates and outcomes for the United States, 1990-2008,

for pregnancies, live births, estimated intra-uterine deaths and induced abortions by race and ethnicity. Also provided were total YPLL and death counts in North Carolina (2008) for all causes of death by race and ethnicity.

The United States Census Bureau, U.S. Department of

Commerce, provided annual mid-year (2008) estimates

of the resident population of North Carolina by sex, race

and Hispanic origin.

2.2. Fetal Loss Estimation

The provision of induced abortion services is predicated on the assumption that the pregnancy has been

clinically confirmed. In order to accurately reflect intrauterine deaths in the absence of induced abortion, our

definition and estimate of intra-uterine deaths excluded

those that occur prior to implantation and included all of

those that might occur at all gestational ages; i.e., miscarriages and stillbirths. Since fetal deaths that occur at

less than 20 weeks, i.e. miscarriages are not reported in

North Carolina it was necessary that we apply the CDC

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) race-specific intra-uterine death estimates to induced abortions in

North Carolina in order to avoid overestimating live

births in the absence of induced abortion. Of all fetal loss

estimate methodologies during recognized pregnancies,

the CDC-NCHS method returns the highest fetal loss

rates and therefore provides the most conservative estimate of potential lives lost to induced abortion [13-16].

The multiple sources of data, consistency of reporting

OPEN ACCESS

10

J. Studnicki et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 4 (2014) 8-12

over an extended period of time, and careful attention to

statistical significance of the estimates assures the most

valid estimate of pregnancy rates and outcomes possible.

The components of the CDC method of estimation,

briefly summarized, are as follows:

1) Live births are based on complete counts reported

on birth certificates provided by every state to the NCHS

through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program (VSCP)

[17,18];

2) Estimates of induced abortions are from abortion

surveillance information collected by the CDCs National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion (NCCDPHP) from most states (including

North Carolina); these estimates are adjusted to national

totals by the Guttmacher Institute from surveys of all

known abortion providers [19,20];

3) Intra-uterine death estimates are derived from the

pregnancy history data collected by the National Survey

of Family Growth (NSFG), NCHS; estimates are based

on the proportion of pregnancies which ended in fetal

loss during the three most recent NSFG survey cycles for

adults (age 20 - 44), and the four most recent NSFG survey cycles for teens under 20. Unlike vital statistics data

which are generally limited to fetal losses at 20 weeks or

more gestation, the NSFG data include losses at all gestational points.

2.3. Analysis

Results were determined by:

1) Establishing national (2008) estimates of fetal loss

rates [fetal losses/(live births + fetal losses)] for NH

whites and NH blacks; 2) Applying those fetal loss rates

to the (2008) North Carolina NH white and NH black

number of induced abortions; 3) Subtracting those estimated fetal losses from the total induced abortions to

derive the estimated number of live births averted by

induced abortions; 4) Multiplying those estimated

averted births by 75 years to determine the total YPLL

due to induced abortions before age 75 (YPLL 75); 5)

Determining YPLL 75 for every cause using both North

Carolina detailed mortality data and the CDC (WISQARS YPLL 75) categories for reporting; and, 6) Comparing the contributions to the total YPLL 75 from all

other major causes.

3. RESULTS

In 2008 in North Carolina, 12.9% of NH white and

27% of NH black pregnancies were terminated by induced abortions (Table 1). Fetal loss rates totaled for all

gestational periods estimated from national data were

21% for NH whites and 23.7% for NH blacks. Applied to

the North Carolina induced abortions in 2008, there were

2267 estimated fetal losses and 8530 live births averted

for NH whites; and 2811 estimated fetal losses and 9050

live births averted for NH blacks (Table 2).

For NH whites, induced abortions in 2008 contributed

59% of total YPLL 75, and 1.5 times the total YPLL 75

from all other causes combined. For NH blacks, induced

abortions in 2008 contributed 76% of total YPLL 75 and

3.2 times the total YPLL 75 from all other causes combined. Induced abortions contributed 3.6 times the YPLL

75 accumulated from the three major chronic diseases

(malignant neoplasm, heart disease, cerebrovascular)

combined for NH whites; and 8.7 times for NH blacks

(Table 3). Despite the magnitude of the contribution of

induced abortions to YPLL 75 for both NH whites and

NH blacks, and the very large racial disparity in the rate

per 100,000 population, there were even wider differences in the rates for other causes. YPLL 75 NH black

rates per 100,000 were 10.9 times higher than NH whites

for HIV, 5.6 times higher for homicide and 4.4 times

higher for both hypertension and the perinatal conditions.

NH white YPLL 75 rates were actually higher than NH

black rates for suicide, unintentional injuries, chronic

lower respiratory disease and liver disease.

4. DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated that induced abortion is

the overwhelmingly predominant contributing cause of

years of preventable potential lives lost in the North Carolina population, and NH blacks are disproportionately

affected. A particular strength of this study is that the

validity and accuracy of these objective estimates are

free of subjective points of view, and attendant value

judgments, derived from any ideological, religious, poli-

Table 1. Pregnancy outcomes by race/ethnicity, North Carolina, 2008.

NH White

NH Black

NH Other

Hispanic

Unknown

Total

Pregnancies

83,228

43,339

7106

24,390

807

158,870

Live births

72,014

31,108

6017

21,619

130,758

Fetal deaths (>20 weeks)

417

370

32

59

878

Induced abortionsno. (%)*

10,797 (12.9)

11,861 (27.4)

1507 (14.8)

2712 (11.1)

807

27,234

Induced abortions as a percent of total pregnancies; Fetal deaths <20 weeks not reported.

Copyright 2014 SciRes.

OPEN ACCESS

J. Studnicki et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 4 (2014) 8-12

tical or cultural perspective. These analyses and results

are completely independent of answers to questions such

as whether a fetus has the same moral status as a newborn [21]; whether some induced abortions are more

justified than others, as in the case of rape or incest;

whether the intentionality of the woman was to abort

or continue the pregnancy to a live birth [22]; or, whether

abortions should be prohibited beyond some gestational

period such as 28 weeks.

Except for the statistical differences in the likelihood

of surviving to a live birth based on gestational age, included in the method of fetal loss estimation, no attempt

is made to impute differential value or quality to

these years of life lost in any way. The magnitude and

racial disparity in potential lives lost to induced abortion

described in this research should provoke discussion and

inform policy. However, the identical objective information will likely be used to make contrasting arguments

related to the motivation for and outcomes of induced

abortion; for example, that induced abortion is both a

major method of government cost savings and the principal instrument of racial genocide [23,24].

The YPLL method has certain limitations. The cutoff

age, 75 in our case, is somewhat arbitrary and does not

acknowledge lives lived beyond a certain point nor include them in the calculation of years lost. YPLL also

tends to undervalue lives lost from chronic diseases since

Table 2. YPLL 75 from induced abortions, North Carolina,

2008.

NH White

NH Black

CDC estimated national fetal loss rate*

21%

23.7%

Estimated fetal losses

2267

2811

Live births averted

8530

9050

Total YPLL

639,750

678,750

10,320

34,708

YPLL rate/100,000

11

Fetal losses/(Fetal losses + live births); NH White 2008 population6,198,806; NH Black 2008 population-1,955,575.

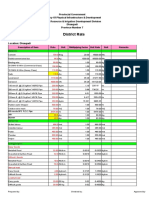

Table 3. Years of potential life lost before age 75 (YPLL 75), all causes, 2008, NH Whites and NH Blacks, North Carolina.

NH Black*

NH White*

Cause

YPLL

Rate/100,000

YPLL

Rate/100,000

Black/White Rate Ratio

All

889,990

45,510

1,076,993

17,374

2.6

Induced abortion

678,750

34,708

639,750

10,320

3.4

Malignant neoplasms

36,575

1870

100,544

1622

1.1

Unintentional injury

21,031

1075

79,416

1281

0.8

Heart disease

32,978

1686

68,094

1098

1.5

Suicide

4332

221

27,105

437

0.5

Chronic lower respiratory disease

3864

197

15,608

252

0.8

Perinatal period

19,602

1002

14,019

226

4.4

Liver disease

3038

155

11,127

179

0.8

Cerebrovascular

8241

421

10,475

169

2.5

Congenital anomalies

5671

290

10,250

165

1.7

Diabetes Mellitus

7040

359

9357

151

2.4

Homicide

14,373

735

8137

131

5.6

Influenza and pneumonia

2185

112

5127

83

1.3

Septicemia

3551

182

5115

82

2.2

Nephritis

3926

201

4855

78

2.5

Viral hepatitis

1140

58

2742

44

1.3

HIV

7042

360

2061

33

10.9

Benign neoplasms

730

37

1782

29

1.3

Hypertension

2177

111

1532

25

4.4

Aortic aneurism

627

32

1402

23

1.4

All others

33,117

1693

58,495

943

1.8

Includes both sexes.

Copyright 2014 SciRes.

OPEN ACCESS

12

J. Studnicki et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 4 (2014) 8-12

they typically occur at older ages. Since NH black life

expectancy was 3.8 years lower than NH whites in 2010,

application of a race-specific life expectancy value could

be used for each race so as not to inflate NH black YPLL

however that would be an atypical application with only

a marginal effect on the results [25]. Finally, results derived from the North Carolina NH white and NH black

induced abortion data in 2008 should not be generalized

to any other specifically defined population-although the

data does suggest that the North Carolina experience

conforms closely to national (US) trends [3].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There is no conflict of interest of any parties contributing to this

study.

REFERENCES

[1]

[2]

Ventura, S.J., Mosher, W.D., Curtin, S.C., Abma, J.C. and

Henshaw, S. (2000) Trends in pregnancies and pregnancy

rates by outcome: Estimates for the United States, National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 21, 56, 1976-1996.

Ventura, S.J., Abma, J.C., Mosher, W.D. and Henshaw,

S.K. (2009) Estimated pregnancy rates for the United

States, 1990-2005: An update. National Vital Statistics

Reports, 58, 1-14.

and reproductive rights. Comment. Lancet, 377, 249-256.

[11] Kliman, H.J., McSweet, J.C. and Levin, Y.A. (2005) Fetal

death: Etiology and pathological findings. Up To Date.

[12] Kost, K. and Henshaw, S. (2012) US teenage pregnancies,

births, and abortions, 2008: National trends by age, race

and ethnicity. The Guttmacher Institute, New York.

[13] Miller, J.F., Williamson, E., Glue, J., Gordon, Y.B., Grudzinskas, J.G. and Sykes, A. (1980) Fetal loss after implantation: A prospective study. Lancet, 2, 554-556.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(80)91991-1

[14] Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, et al. (2003) Conception, early

pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: A population based prospective study. Fertility and Sterility, 79,

577-584.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04694-0

[15] Zinaman, M.D., Clegg, E.D., Brown, C.C., OConnor, J.

and Selevan, S.G. (1996) Estimates of human fertility and

pregnancy loss. Fertility and Sterility, 65, 503-509.

[16] Wilcox, A.J., Treloar, A.E. and Sandler, D.P. (1981) Spontaneous abortion over time: Comparing occurrence in two

cohorts of women a generation apart. American Journal

of Epidemiology, 114, 548-553.

[17] National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. (2013) User

guide to the 2008 natality public use file.

http://ftp.cdc.gov./pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_

Documentation/DVS/natality/UserGuide2008.pdf

[18] Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., Sutton, P.D., Ventura, S.J.,

Mathews, T.J. and Osterman, M.J. (2010). Births: Final

data for 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports, 59, 3-71.

[3]

Ventura, S.J., Curtin, S.C, Abma, J.C. and Henshaw, S.K.

(2012) Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy

outcomes for the United States, 1990-2008. National Vital Statistics Reports, 60, 1-21.

[4]

Gardner, J.W. and Sanborn, J.S. (1990) Years of potential

life lost (YPLL)What does it measure? Epidemiology,

1, 322-329.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199007000-00012

[5]

McDonnell, S., Vossberg, K., Hopkins, R.S. and Mittan,

B. (1998) Using YPLL in health planning. Public Health

Reports, 113, 55-61.

[21] Giubilini, A. and Minerva, F. (2012) After-birth abortion:

Why should the baby live? Journal of Medical Ethics, 39,

261-263.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2011-100411

[6]

Peppard, P.E., Kindig, D., Riemer, A., Dranger, E. and

Remington, P.L. (2003) Wisconsin county health rankings,

2003. Wisconsin Public Health Policy Institute, Madison.

[22] Hammerslough, C.R. (1992) Estimating the probability of

spontaneous abortion in the presence of induced abortion

and vice versa. Public Health Reports, 107, 269-277.

[7]

United Heath Foundation. (2013) Americas health: United Health Foundation state health rankings 2012 Edition.

http://www.americashealthrankings.org/All/YPLL/2012

[8]

Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). (2013) Potential years of life lost.

http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=2095

[23] Covert, B. (2013) How denying woman access to reproductive choices costs taxpayers.

http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2013/07/01/2239101/ab

ortion-contraception-budget/

[9]

CDC, National Center for Health Statistics (1988) Trends

in years of potential life Lost due to infant mortality and

perinatal conditions, 1980-1983 and 1984-1985. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 37, 249-256.

[10] Kelley, M. (2011) Counting stillbirths: Womens health

Copyright 2014 SciRes.

[19] Pazol, K., Zane, S.B., Parker, W.Y., Hall, L.R., Berg, C.

and Cook, D.A. (2011) Abortion surveillanceUnited

States, 2008. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 60, 1-41.

[20] Jones, R.K. and Kooistra, K. (2011) Abortion incidence

and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 43, 41-50.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1363/4304111

[24] Weisbord, R.G. (1973) Birth control and the Black American: A matter of genocide? Demography, 10, 571-590.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2060884

[25] Kochanek, K.D., Arias, E. and Anderson, R.N (2013)

How did cause of death contribute to racial differences in

life expectancy in the United States in 2010? NCHS Data

Brief, 125, 1-8.

OPEN ACCESS

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Daftar PustakaDokument1 SeiteDaftar PustakaTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Sesame On Sperm Quality of Infertile MenDokument6 SeitenEffect of Sesame On Sperm Quality of Infertile MenTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar PustakaDokument1 SeiteDaftar PustakaTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liebenberg Exploration (2010)Dokument7 SeitenLiebenberg Exploration (2010)Tuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar PustakaDokument1 SeiteDaftar PustakaTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perbedaan Efektifitas Pemberian Vitamin E 100 Iu Dengan Aspirin 81 MG Untuk Pencegahan Preeklamsia Pada PrimigravidaDokument5 SeitenPerbedaan Efektifitas Pemberian Vitamin E 100 Iu Dengan Aspirin 81 MG Untuk Pencegahan Preeklamsia Pada PrimigravidaTeguh_Yudha_Adi_WijaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sesame improves sperm quality and male fertilityDokument4 SeitenSesame improves sperm quality and male fertilityAnada KaporinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 NCSE DeafDokument294 Seiten1 NCSE DeafRaf SmileNoch keine Bewertungen

- A 38-Year-Old Welder With Dyspnea and Iron OverloadDokument4 SeitenA 38-Year-Old Welder With Dyspnea and Iron OverloadTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Differentiating P. falciparum and P. vivax with microscopyDokument31 SeitenDifferentiating P. falciparum and P. vivax with microscopyTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Language Teaching and Therapy 2011 Alton 255 67Dokument14 SeitenChild Language Teaching and Therapy 2011 Alton 255 67Tuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Hadir Departemen Neurologi FK Upn "Veteran" - Rsup Persahabatan Jakarta Periode 9 Februari 2015 - 14 Maret 2015 Minggu IDokument3 SeitenDaftar Hadir Departemen Neurologi FK Upn "Veteran" - Rsup Persahabatan Jakarta Periode 9 Februari 2015 - 14 Maret 2015 Minggu ITuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bab Ii Kortikosteroid SistemikDokument1 SeiteBab Ii Kortikosteroid SistemikTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bab IDokument42 SeitenBab ITuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema SyndromeDokument5 SeitenCombined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema SyndromeTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statistical Analysis: Table 1Dokument6 SeitenStatistical Analysis: Table 1Tuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- A 38-Year-Old Welder With Dyspnea and Iron OverloadDokument4 SeitenA 38-Year-Old Welder With Dyspnea and Iron OverloadTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Makalah Case 1 Case Dan LPRDokument4 SeitenMakalah Case 1 Case Dan LPRTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- CT Volumetry of The Liver: Where Does It Stand in Clinical Practice?Dokument9 SeitenCT Volumetry of The Liver: Where Does It Stand in Clinical Practice?Tuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIIS000992601400083XDokument4 SeitenPIIS000992601400083XTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Makalah Klinik Dokter KeluargaDokument2 SeitenMakalah Klinik Dokter KeluargaTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- CT Volumetry of The Liver: Where Does It Stand in Clinical Practice?Dokument9 SeitenCT Volumetry of The Liver: Where Does It Stand in Clinical Practice?Tuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIIS000992601400083XDokument4 SeitenPIIS000992601400083XTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema SyndromeDokument10 SeitenCombined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema SyndromeTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema SyndromeDokument10 SeitenCombined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema SyndromeTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Happy BirthdayDokument4 SeitenHappy BirthdayTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- CoverDokument2 SeitenCoverTuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bab IDokument67 SeitenBab ITuti AlawiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 01 01Dokument232 Seiten01 01Muhammad Al-MshariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Therminol 55Dokument5 SeitenTherminol 55Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- SmithfieldDokument11 SeitenSmithfieldandreea143Noch keine Bewertungen

- Concept PaperDokument6 SeitenConcept Paperapple amanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 2022 Salary Slip SintexDokument1 Seite12 2022 Salary Slip SintexpathyashisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vietnam Snack Market Grade BDokument3 SeitenVietnam Snack Market Grade BHuỳnh Điệp TrầnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kuan Yin 100 Divine Lots InterpretationDokument30 SeitenKuan Yin 100 Divine Lots InterpretationEsperanza Theiss100% (2)

- Causes of DyspneaDokument9 SeitenCauses of DyspneaHanis Afiqah Violet MeowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Chiller 6-Can Mini Refrigerator, Pink K4Dokument1 SeitePersonal Chiller 6-Can Mini Refrigerator, Pink K4Keyla SierraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disha Symbiosis 20th JulyDokument2 SeitenDisha Symbiosis 20th JulyhippieatheartbalewadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance and Mechanical Running Tests of Centrifugal CompressorsDokument5 SeitenPerformance and Mechanical Running Tests of Centrifugal CompressorsVicky KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biosafety FH Guidance Guide Good Manufacturing Practice enDokument40 SeitenBiosafety FH Guidance Guide Good Manufacturing Practice enMaritsa PerHerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Duty Roster Class IV JulyDokument2 SeitenDuty Roster Class IV JulyTayyab HassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Push Pull Legs RoutineDokument4 SeitenThe Push Pull Legs RoutineSparkbuggy57% (7)

- How To Develop A Super MemoryDokument12 SeitenHow To Develop A Super Memoryazik zakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- HBV Real Time PCR Primer Probe Sequncence PDFDokument9 SeitenHBV Real Time PCR Primer Probe Sequncence PDFnbiolab6659Noch keine Bewertungen

- Undas Deployment PadsDokument15 SeitenUndas Deployment PadsVic NairaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JPK-056-07-L-1754 - Rev 0Dokument245 SeitenJPK-056-07-L-1754 - Rev 0aibek100% (1)

- Practical Research 1 Quarter 1 - Module 10: Through The SlateDokument10 SeitenPractical Research 1 Quarter 1 - Module 10: Through The SlateMark Allen Labasan100% (1)

- Seguridad Boltec Cable PDFDokument36 SeitenSeguridad Boltec Cable PDFCesar QuintanillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Small Gas Turbines 4 LubricationDokument19 SeitenSmall Gas Turbines 4 LubricationValBMSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Easy and Successful Plumbing Methods You Can Now Applyhslhj PDFDokument2 SeitenEasy and Successful Plumbing Methods You Can Now Applyhslhj PDFbeartea84Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Congressional Committee and Philippine Policymaking: The Case of The Anti-Rape Law - Myrna LavidesDokument29 SeitenThe Congressional Committee and Philippine Policymaking: The Case of The Anti-Rape Law - Myrna LavidesmarielkuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Khatr Khola ISP District RatesDokument56 SeitenKhatr Khola ISP District RatesCivil EngineeringNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flexible and Alternative Seating: in ClassroomsDokument5 SeitenFlexible and Alternative Seating: in ClassroomsweningNoch keine Bewertungen

- India Vision 2020Dokument9 SeitenIndia Vision 2020Siva KumaravelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Dairy Subsidies in NepalDokument123 SeitenImpact of Dairy Subsidies in NepalGaurav PradhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pakistan List of Approved Panel PhysicianssDokument5 SeitenPakistan List of Approved Panel PhysicianssGulzar Ahmad RawnNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAPEH 2 SBC 2nd Quarterly AssesmentDokument5 SeitenMAPEH 2 SBC 2nd Quarterly AssesmentReshiele FalconNoch keine Bewertungen

- Density of Aggregates: ObjectivesDokument4 SeitenDensity of Aggregates: ObjectivesKit Gerald EliasNoch keine Bewertungen