Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Picasso Sculpture at MoMA

Hochgeladen von

Nancy TangCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Picasso Sculpture at MoMA

Hochgeladen von

Nancy TangCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Tang 1

Nancy Tang

Art Humanities: Masterpieces of Western Art

Exhibition Review: Picasso Sculpture

September 30, 2015

Picasso in Three Dimensions

One should expect a visit to the Museum of Modern Art on a weekend to be crowded, but

Picasso Sculpture had an almost surprising amount of people blocking every entryway, intently

reading the placards on the wall at the beginning of each new gallery space. Over 100 works are

arranged chronologically, covering each episode of sculpture making Picasso went through

(MoMA). Beginning with some of Picassos drawings which reference sculpture on the wall

opposite the escalators, viewers are ushered through the eleven galleries in a very logical manner.

The first room has almost a dozen of Picassos earliest works in sculpting and interpreting the

human form, which are seen as the first Cubist sculptures. Compared to the works seen later on

in the exhibition, these worksproduced between 1902 and 1909are relatively tame and

conventional (MoMA). In retrospect, it was like going to a beach on a slightly too cold day and

just dipping your toes into the water for a bit.

We are constantly reminded that Picasso had no formal training as a sculptor. As opposed

to painting, which he earned his living through, sculpture was a more personal and perhaps even

more experimental realm. The second gallery chronicles Picassos work from 1912 to 1915. By

this point, his work is firmly entrenched in the idea of representing Cubism in a threedimensional space and exploring the use of more unconventional materials. Six versions of

Glass of Absinthe were cast in bronze from one wax mold and decorated with paint. Speaking on

Tang 2

this project, Picasso stated, "I was interested in the relation between the real spoon and the

modeled glass. In the way they clashed with each other" (MoMA). The idea of clashing materials

continues well into Picassos career as a sculptor, and can be seen as one of the most prominent

features of his work up until the 1950s. Other pieces include the two guitars, one which is made

of paper, cardboard, and twine, and the metal version. These flatter, wall mounted pieces are

essentially an expansion upon collage, an art form favored by Picassos friend, and less-famous

Cubist contemporary, Georges Braque. There are few pieces displayed on the wall throughout the

exhibition, making these particularly memorable and important.

Picasso stopped sculpting for over ten years, which included World War 1. He began

again in 1927, when he was asked to create a monument for the French poet Guillaume

Apollinaire. The sketches and models behind this attempt, which look like black lines on paper,

were drastically different from Picassos previous work and utilize a revolutionary technique

using welding and iron rods, developed by Picassos friend Julio Gonzlez. This gallery also

features Metamorphosis I and Metamorphosis II, a theme Picasso also explored in drawings and

paintings. In this sense, they can be interpreted to stand for Picassos own growth and change as

a sculptor over this period of time.

The next rooms show Picassos work after he bought a property in Boisgeloup, and

converted it into a sculpture studio (MoMA). From this point onwards, through another war and

until the last large room of sheet metal sculptures, much of Picassos work seems more solid, but

also more absurd. A womans head is turned into a phallus, a baboons face is made of a car. I

personally found this to be kind of gimmicky at some points, but it was still worth seeing.

The last gallery, showing sheet metal sculptures made from 1954 to 1964 is a logical

ending, both in the sense that these pieces were created toward the end of Picassos life and that

Tang 3

they are more unified works, like those seen at the beginning of the exhibition. Nonetheless,

none of the pieces here are uniform or boring, and they create a wholly satisfying closing.

Because of the curators choice to arrange pieces in groups based on time, we see much

of Picassos work does not have a traceable pattern. He is constantly jumping around, with

different media and different subject matter, sometimes settling on one thing, but just as quickly

and erratically moving on. The chronological organization of this exhibition is essential to that

understanding. Additionally, none of the individual galleries seemed too crowded. The perfect

amount of space is left to weave between people and pieces, while still being able to survey the

room completely. Despite this, the exhibition was still quite overwhelming and dizzyingly

complete. I had the distinct feeling that no matter how much time I spent wandering around the

exhibition, I would never really have a comprehensive understanding of everything there.

Despite this, or perhaps because of this, I would encourage anyone with the slightest interest in

sculpture, Picasso, or art in general to visit this exhibition. It breaches the conception most

people have of Picasso as a painter, as well as the ideas of sculpture embedded into our minds as

a society, which would generally show more classical works. Although Picasso is by no means

my favorite as a sculptor, exploring this exhibition gave me a more concrete idea of him as an

artist and person as a whole, and of my own tastes.

Tang 4

Works Cited

MoMA. Pablo Picasso. Glass of Absinthe. Paris, Spring 1914. MoMA, n.d. Web. 29 Sept. 2015.

MoMA. Pablo Picasso. Project for a Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire. 1962; Enlarged

Version after 1928 Original Maquette. MoMA, n.d. Web. 28 Sept. 2015.

MoMA. Pablo Picasso. Glass of Absinthe. Paris, Spring 1914. MoMA, n.d. Web. 29 Sept. 2015.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Picasso y Braque Pioneros Del Cubismo Resepña Moma (En Ingles)Dokument4 SeitenPicasso y Braque Pioneros Del Cubismo Resepña Moma (En Ingles)Pedro De Las HerasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art Analysis Still Life With A Bottle of RumDokument2 SeitenArt Analysis Still Life With A Bottle of RumDylan ViguillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroDokument4 SeitenHoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroVal RavagliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ann Temkin - Ab Ex at MoMADokument5 SeitenAnn Temkin - Ab Ex at MoMAcowley75Noch keine Bewertungen

- PM Picasso Eng FinalDokument13 SeitenPM Picasso Eng FinalberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crimp Museums Old Librarys New SubjectDokument12 SeitenCrimp Museums Old Librarys New Subjectst_jovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pablo PicassoDokument16 SeitenPablo Picassoapi-193496952Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lyon - Introduction To Picasso and BraqueDokument8 SeitenLyon - Introduction To Picasso and BraquehofelstNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Pablo PicassoDokument7 SeitenResearch Paper Pablo Picassoegabnlrhf100% (3)

- CubismDokument3 SeitenCubismA M ZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art History Research PaperDokument8 SeitenArt History Research PaperVictor KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay CubismDokument6 SeitenEssay Cubismnrpelipig100% (1)

- Paris Without End: On French Art Since World War IVon EverandParis Without End: On French Art Since World War IBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- Art by Instruction and The Pre-History of Do It: Bruce AltshulerDokument9 SeitenArt by Instruction and The Pre-History of Do It: Bruce AltshulerJúlio MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Masters Of Ukioye - A Complete Historical Description Of Japanese Paintings And Color Prints Of The Genre SchoolVon EverandThe Masters Of Ukioye - A Complete Historical Description Of Japanese Paintings And Color Prints Of The Genre SchoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- CollageDokument13 SeitenCollageRajat SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Search of a Lost Avant-Garde: An Anthropologist Investigates the Contemporary Art MuseumVon EverandIn Search of a Lost Avant-Garde: An Anthropologist Investigates the Contemporary Art MuseumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Last Light: How Six Great Artists Made Old Age a Time of TriumphVon EverandLast Light: How Six Great Artists Made Old Age a Time of TriumphNoch keine Bewertungen

- Picasso's Blue Period - WikipediaDokument24 SeitenPicasso's Blue Period - WikipediaDinesh RajputNoch keine Bewertungen

- Picasso and The War YearsDokument260 SeitenPicasso and The War YearsGagrigore100% (2)

- HH Arnason - Cubism (Ch. 10)Dokument38 SeitenHH Arnason - Cubism (Ch. 10)KraftfeldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Picasso and Spanish ModernityDokument31 SeitenPicasso and Spanish ModernityManuel Miranda-parreñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CubismDokument138 SeitenCubismaansoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Collage: 1 HistoryDokument11 SeitenCollage: 1 HistorytanitartNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in ArtVon EverandThe Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in ArtBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- Discuss The Ideas Behind The Development of Cubism FINALDokument16 SeitenDiscuss The Ideas Behind The Development of Cubism FINALNour AndreiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expressionism CubismDokument12 SeitenExpressionism CubismAegina Yricka VelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Looking How To Read Modern and Contemporary Art (Esplund, Lance) (Z-Library)Dokument240 SeitenThe Art of Looking How To Read Modern and Contemporary Art (Esplund, Lance) (Z-Library)madhu smriti100% (1)

- The Venetian Painters of the Renaissance Third EditionVon EverandThe Venetian Painters of the Renaissance Third EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avant Garde: Au Bon Marche 1913 by Pablo Picasso.Dokument6 SeitenAvant Garde: Au Bon Marche 1913 by Pablo Picasso.Youmna AdnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern ArtVon EverandPicasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern ArtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cubism (Edited)Dokument13 SeitenCubism (Edited)Debashree MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cubism and Abstract Art1936 Cubism and Abstract Art Exhibition-1Dokument21 SeitenCubism and Abstract Art1936 Cubism and Abstract Art Exhibition-1Anonymous DLznRbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art by Instruction and The Pre-History of Do It With Postscript-1 PDFDokument17 SeitenArt by Instruction and The Pre-History of Do It With Postscript-1 PDFmerelgarteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robert Smithson What Is A Museum A Dialogue Between Allan Kaprow and Robert Smithson 1967Dokument13 SeitenRobert Smithson What Is A Museum A Dialogue Between Allan Kaprow and Robert Smithson 1967SaulAlbert100% (1)

- Moma Pollock One PreviewDokument10 SeitenMoma Pollock One PreviewMaria Jose VannicolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Le Japon Artistique: Japanese Floral Pattern Design in the Art Nouveau EraVon EverandLe Japon Artistique: Japanese Floral Pattern Design in the Art Nouveau EraBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- Modern Art in The 20th Century PDFDokument14 SeitenModern Art in The 20th Century PDFChinenn Daang75% (4)

- Reaction Paper - ROLLY JHON R. CURAYDokument3 SeitenReaction Paper - ROLLY JHON R. CURAYPAUL STEPHEN MALUPANoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline of ReportDokument7 SeitenOutline of ReportAujianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pablopicasso Portfolio3Dokument4 SeitenPablopicasso Portfolio3api-352757193Noch keine Bewertungen

- Art CubismDokument23 SeitenArt CubismBraiyle ENoch keine Bewertungen

- Masterpieces of The J. Paul Getty Museum Europian SculptureDokument130 SeitenMasterpieces of The J. Paul Getty Museum Europian Sculptureekoya100% (4)

- Pablo Picasso: Founder of The Cubist MovementDokument19 SeitenPablo Picasso: Founder of The Cubist MovementMarina GeghamyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pablo Picasso - CatalogueDokument32 SeitenPablo Picasso - CatalogueGrapes als Priya100% (3)

- PicassoDokument1 SeitePicassoapi-294643937Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Painters of China (Max Loehr) (Z-Library)Dokument332 SeitenThe Great Painters of China (Max Loehr) (Z-Library)Manual do Robot100% (2)

- Camille Pissaro FinalDokument18 SeitenCamille Pissaro FinalSakshi JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art MovementDokument25 SeitenArt MovementAjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magdalena AbakanowiczDokument1 SeiteMagdalena AbakanowiczadinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lowbrow (Art Movement)Dokument5 SeitenLowbrow (Art Movement)fredmacedocadastros0% (1)

- Art History Timeline: Art Periods/ Movements Dates Chief Artists and Major Works Characteristics Historical EventsDokument6 SeitenArt History Timeline: Art Periods/ Movements Dates Chief Artists and Major Works Characteristics Historical EventsKenneth Mora RiofloridoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern Art: Ars Libri LTDDokument47 SeitenModern Art: Ars Libri LTDju1976Noch keine Bewertungen

- CollageDokument84 SeitenCollageVirgilio Biagtan100% (1)

- Ass 2Dokument17 SeitenAss 2enne ZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art Since 1945Dokument13 SeitenArt Since 1945Marwa IbrahimNoch keine Bewertungen

- ExpressionismDokument13 SeitenExpressionismBrinzei LucianNoch keine Bewertungen

- G10 Arts - M2 - W4-5Dokument10 SeitenG10 Arts - M2 - W4-5Teacher April CelestialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mapeh 10 Arts Quarter 1 - Module - 3 PDFDokument33 SeitenMapeh 10 Arts Quarter 1 - Module - 3 PDFPayos Joey100% (4)

- אמנות פוסטמודרניתDokument290 Seitenאמנות פוסטמודרניתlev2468Noch keine Bewertungen

- Land ArtDokument5 SeitenLand ArtnatalirajcinovskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DadaismDokument9 SeitenDadaismtulips7333Noch keine Bewertungen

- More Light - Lawrence Ferlinghetti's Wide-Angle Vision.Dokument4 SeitenMore Light - Lawrence Ferlinghetti's Wide-Angle Vision.Alexandra ConstantinoviciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claes Oldenburg: Soft Bathtub (Model) - Ghost Version by Claes OldenburgDokument2 SeitenClaes Oldenburg: Soft Bathtub (Model) - Ghost Version by Claes OldenburgjovanaspikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expressionist Architecture PDFDokument2 SeitenExpressionist Architecture PDFJames100% (1)

- STEIN, Gertrude - The Making of AmericansDokument11 SeitenSTEIN, Gertrude - The Making of Americansgaby cepedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grva Unit 2 Elaborate-Naboye, Lance Martin 0.Dokument6 SeitenGrva Unit 2 Elaborate-Naboye, Lance Martin 0.LANCE MARTIN NABOYENoch keine Bewertungen

- Afro Surrealism PDFDokument3 SeitenAfro Surrealism PDFBill TolesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstract ArtDokument9 SeitenAbstract Artapi-193496952Noch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary ArtDokument4 SeitenContemporary Artlekz reNoch keine Bewertungen

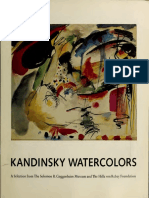

- Kandinsky WatercolorsDokument84 SeitenKandinsky WatercolorsVianey Sarl100% (2)

- Ged 108-Module 2-Week 5-Brief History of ArtDokument29 SeitenGed 108-Module 2-Week 5-Brief History of ArtJC FuriscalNoch keine Bewertungen

- ARTS 10 Read and Answer (Write Answers On 1 Whole Sheet of Paper-ANSWERS ONLY)Dokument8 SeitenARTS 10 Read and Answer (Write Answers On 1 Whole Sheet of Paper-ANSWERS ONLY)Janine Jerica JontilanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- René François Ghislain MagritteDokument3 SeitenRené François Ghislain MagritteEla DatingalingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts Exam 08-09 1st TermDokument10 SeitenArts Exam 08-09 1st TermlordsonxxxNoch keine Bewertungen

- .Artsg10.q1.w2-5.ursabia, May Jean & MirandaDokument23 Seiten.Artsg10.q1.w2-5.ursabia, May Jean & MirandaBoyet Saranillo FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- DCV - November 2021Dokument9 SeitenDCV - November 2021ArtdataNoch keine Bewertungen