Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

IPL Case List 2 Digest

Hochgeladen von

Mis DeeCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

IPL Case List 2 Digest

Hochgeladen von

Mis DeeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

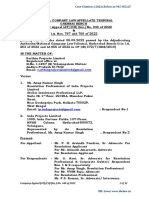

McDONALDS CORPORATION v.

MACJOY

CORPORATION

G.R. No. 166115

Feb ruary 2, 2007

FASTFOOD

Issue:

1.

2.

Facts:

On 14 March 1991, respondent MacJoy Fastfood

Corporation, a domestic corporation engaged in the

sale of fast food products in Cebu City, filed with the

then Bureau of Patents, Trademarks and Technology

Transfer (BPTT), now the Intellectual Property Office

(IPO), an application for the registration of the

trademark "MACJOY & DEVICE" for fried chicken,

chicken barbeque, burgers, fries, spaghetti, palabok,

tacos, sandwiches, halo-halo and steaks under

classes 29 and 30 of the International Classification of

Goods.

Petitioner McDonalds Corporation, filed a verified

Notice of Opposition against the respondents

application claiming that the trademark "MACJOY &

DEVICE" so resembles its corporate logo, otherwise

known as the Golden Arches or "M" design, and its

marks "McDonalds," McChicken," "MacFries," etc.

(hereinafter MCDONALDS marks) such that when

used on identical or related goods, the trademark

applied for would confuse or deceive purchasers into

believing that the goods originate from the same

source or origin.

Also, petitioner alleged that the respondents use and

adoption in bad faith of the "MACJOY & DEVICE" mark

would falsely tend to suggest a connection or affiliation

with petitioners restaurant services and food products,

thus, constituting a fraud upon the general public and

further cause the dilution of the distinctiveness of

petitioners registered and internationally recognized

MCDONALDS marks to its prejudice and irreparable

damage.

IPO ruled that the predominance of the letter "M," and

the prefixes "Mac/Mc" in both the "MACJOY" and the

"MCDONALDS" marks lead to the conclusion that

there is confusing similarity between them especially

since both are used on almost the same products

falling under classes 29 and 30 of the International

Classification of Goods, i.e., food and ingredients of

food, sustained the petitioners opposition and rejected

the respondents application. (IPO used the dominancy

test)

IPO denied MR. CA reversed the IPO decision, ruling

that there was no confusing similarity between the

marks "MACJOY" and "MCDONALDS," for the ff.

reasons:

1. The word "MacJoy" is written in round script while

the word "McDonalds" is written in single stroke

gothic;

2. The word "MacJoy" comes with the picture of a

chicken head with cap and bowtie and wings sprouting

on both sides, while the word "McDonalds" comes with

an arches "M" in gold colors, and absolutely without

any picture of a chicken;

3. The word "MacJoy" is set in deep pink and white

color scheme while "McDonalds" is written in red,

yellow and black color combination;

4. The faade of the respective stores of the parties

are entirely different. Respondents restaurant is set

also in the same bold, brilliant and noticeable color

scheme as that of its wrappers, containers, cups, etc.,

while Petitioners restaurant is in yellow and red colors,

and with the mascot of "Ronald McDonald" being

prominently displayed therein."

Ratio:

1.

W/N the dominancy test should be applied, instead of

the holistic test.

W/N there is a confusing similarity between MACJOY

and MCDONALDS trademarks as to justify the IPOs

rejection of Macjoys trademark application

YES.

In determining similarity and likelihood of confusion,

jurisprudence has developed two tests, the dominancy

test and the holistic test. The dominancy test focuses

on the similarity of the prevalent features of the

competing trademarks that might cause confusion or

deception. In contrast, the holistic test requires the

court to consider the entirety of the marks as applied to

the products, including the labels and packaging, in

determining confusing similarity.

In recent cases with a similar factual milieu as

here, the Court has consistently used and applied

the dominancy test in determining confusing

similarity or likelihood of confusion between

competing trademarks.

Under the dominancy test, courts give greater weight

to the similarity of the appearance of the product

arising from the adoption of the dominant features of

the registered mark, disregarding minor differences.

Courts will consider more the aural and visual

impressions created by the marks in the public mind,

giving little weight to factors like prices, quality, sales

outlets and market segments.

Applying the dominancy test to the instant case,

the

Court

finds

that

herein petitioners

"MCDONALDS" and respondents "MACJOY"

marks are confusingly similar with each other such

that an ordinary purchaser can conclude an

association or relation between the marks

2.

YES.

Both marks use the corporate "M" design logo and the

prefixes "Mc" and/or "Mac" as dominant features. The

first letter "M" in both marks puts emphasis on the

prefixes "Mc" and/or "Mac" by the similar way in which

they are depicted i.e. in an arch-like, capitalized and

stylized manner.

It is the prefix "Mc," an abbreviation of "Mac," which

visually and aurally catches the attention of the

consuming public.

Both trademarks are used in the sale of fastfood

products. Indisputably, the respondents trademark

application for the "MACJOY & DEVICE" trademark

covers goods under Classes 29 and 30 of the

International Classification of Goods, namely, fried

chicken, chicken barbeque, burgers, fries, spaghetti,

etc. McDonalds registered trademark covers goods

similar if not identical to those covered by the

respondents application.

Predominant features such as the "M," "Mc," and

"Mac" appearing in both McDonalds marks and

the MACJOY & DEVICE" easily attract the attention

of

would-be

customers. Even non-regular

customers of their fastfood restaurants would

readily notice the predominance of the "M" design,

"Mc/Mac" prefixes shown in both marks. Such that

the common awareness or perception of

customers that the trademarks McDonalds mark

and MACJOY & DEVICE are one and the same, or

an affiliate, or under the sponsorship of the other

is not far-fetched.

By reason of the respondents implausible and

insufficient explanation as to how and why out of the

many choices of words it could have used for its tradename and/or trademark, it chose the word "MACJOY,"

the only logical conclusion deducible therefrom is that

the respondent would want to ride high on the

established reputation and goodwill of the

MCDONALDs marks, which, as applied to petitioners

restaurant business and food products, is undoubtedly

beyond question.

When one applies for the registration of a trademark or

label which is almost the same or very closely

resembles one already used and registered by

another, the application should be rejected and

dismissed outright, even without any opposition on the

part of the owner and user of a previously registered

label or trademark, this not only to avoid confusion on

the part of the public, but also to protect an already

used and registered trademark and an established

goodwill.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is GRANTED. Accordingly,

the assailed Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals in

CA-G.R. SP NO. 57247, are REVERSED and SET ASIDE and

the Decision of the Intellectual Property Office in Inter Partes

Case No. 3861 is REINSTATED.

PHILIPPINE REFINING CO., INC. vs. NG SAM G.R. No. L26676. July 30, 1982

Facts:

Private respondent filed with the Philippine Patent Office an

application for registration of the trademark "CAMIA" for his

product, ham, which falls under Class 47 (Foods and

Ingredients of Food).

Petitioner opposed the application claiming that it first used said

trademark on his products: lard, butter, cooking oil, abrasive

detergents, polishing materials and soap of all kinds, some of

which are likewise classified under Class 47.

The trademark "CAMIA" was first used in the Philippines by

petitioner on its products in 1922 and registered the same in

1949

On November 25, 1960, respondent Ng Sam, a Chinese citizen

residing in Iloilo City, filed an application with the Philippine

Patent Office for registration of the identical trademark "CAMIA"

for his product, ham, which likewise falls under Class 47.

Alleged date of first use of the trademark by respondent was on

February 10, 1959.

Director of Patents rendered a decis ion allowing registration of

the trademark "CAMIA" in favor of Ng Sam finding that `the

goods of the parties are not of a character which purchasers

would be likely to attribute to a common origin.

Issue/Answer:

WON the product of respondent Ng Sam, which is ham, and

those of petitioner consisting of lard, butter, cooking oil and

soap are so related that the use of the same trademark

"CAMIA'' on said goods would likely result in confusion as to

their source Atty. Eric Recalde or origin./ negative

Ratio Decidendi:

The right to a trademark is a limited one, in the sense that

others may use the same mark on unrelated goods.

The mere fact that one person has adopted and used a

trademark on his goods does not prevent the adoption and use

of the same trademark by others on articles of a different

description.

Where no confusion is likely to arise, as in this case, registration

of a similar or even identical mark may be allowed.

The term "CAMIA" is descriptive of a whole genus of garden

plants with fragrant white flowers.

A trademark is designed to identify the user. But it should be so

distinctive and sufficiently original as to enable those who come

into contact with it to recognize instantly the identity of the user.

"It must be affirmative and definite, significant and distinctive,

capable to indicate origin.

If a mark is so commonplace that it cannot be readily

distinguished from others, then it is apparent that it cannot

identify a particular business; and he who first adopted it cannot

be injured by any subsequent appropriation or imitation by

others, and the public will not be deceived."]

While ham and some of the products of petitioner are classified

under Class 47 (Foods and Ingredients of Food), this alone

cannot serve as the decisive factor in the resolution of whether

or not they are related goods.

Emphasis should be on the similarity of the products involved

and not on the arbitrary classification or general description of

their properties or characteristics.

Opposer's products are ordinary day-to-day household items

whereas ham is not necessarily so. Thus, the goods of the

parties are not of a character which purchasers would be likely

to attribute to a common origin."

The business of the parties are noncompetitive and their

products so unrelated that the use of identical trademarks is not

likely to give rise to confusion, much less cause damage to

petitioner.

provision:

Section 4(d) of Trademark law "a mark which consists of or

comprises a mark or trade name which so resembles a m ark or

trade name registered in the Philippines or a mark or trade

name previously used in the Philippines by another and not

abandoned, as to be likely, when applied to or used in

connection with the goods, business services of the applicant,

to cause confusion or mistake or to deceive purchasers."

G.R. No. 154491

November 14, 2008

COCA-COLA BOTTLERS, PHILS., INC. (CCBPI), Naga Plant,

petitioner,

vs.

QUINTIN J. GOMEZ, a.k.a. "KIT" GOMEZ and DANILO E.

GALICIA, a.k.a. "DANNY GALICIA", respondents.

FACTS:

Coca-Cola applied for a search warrant against Pepsi for

hoarding Coke empty bottles in Pepsi's yard in Concepcion

Grande, Naga City, an act allegedly penalized as unfair

competition under the IP Code. Coca-Cola claimed that the

bottles must be confiscated to preclude their illegal use,

destruction or concealment by the respondents. In support of

the application, Coca-Cola submitted the sworn statements of

three witnesses: Naga plant representative Arnel John Ponce

said he was informed that one of their plant security guards had

gained access into the Pepsi compound and had seen empty

Coke bottles; acting plant security officer Ylano A. Regaspi

said he investigated reports that Pepsi was hoarding large

quantities of Coke bottles by requesting their security guard to

enter the Pepsi plant and he was informed by the security guard

that Pepsi hoarded several Coke bottles; security guard Edwin

Lirio stated that he entered Pepsi's yard on July 2, 2001 at 4

p.m. and saw empty Coke bottles inside Pepsi shells or cases.

Municipal Trial Court (MTC) Executive Judge Julian C. Ocampo

of Naga City, after taking the joint deposition of the witnesses,

issued Search Warrant No. 2001-01 to seize 2,500 Litro and

3,000 eight and 12 ounces empty Coke bottles at Pepsi's Naga

yard for violation of Section 168.3 (c) of the IP Code.

In their counter-affidavits, Galicia and Gomez claimed that the

bottles came from various Pepsi retailers and wholesalers who

included them in their return to make up for shortages of empty

Pepsi bottles; they had no way of ascertaining beforehand the

return of empty Coke bottles as they simply received what had

been delivered; the presence of the bottles in their yard was not

intentional nor deliberate.

The respondents also filed motions for the return of their shells

and to quash the search warrant. Coca-Cola opposed the

motions as the shells were part of the evidence of the crime,

arguing that Pepsi used the shells in hoarding the bottles. It

insisted that the issuance of warrant was based on probable

cause for unfair competition under the IP Code, and that the

respondents violated R.A. 623, the law regulating the use of

stamped or marked bottles, boxes, and other similar containers.

The MTC issued the first assailed order denying the twin

motions. It explained there was an exhaustive examination of

the applicant and its witnesses through searching questions and

that the Pepsi shells are prima facie evidence that the bottles

were placed there by the respondents.

The MTC denied the motion for reconsideration in the second

assailed order, explaining that the issue of whether there was

unfair competition can only be resolved during trial.

The respondents responded by filing a petition for certiorari

under Rule 65 of the Revised Rules of Court before the

Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Naga City on the ground that the

subject search warrant was issued without probable cause and

that the empty shells were neither mentioned in the warrant nor

the objects of the perceived crime.

The RTC voided the warrant for lack of probable cause and the

non-commission of the crime of unfair competition, even as it

implied that other laws may have been violated by the

respondents. The RTC, though, found no grave abuse of

discretion on the part of the issuing MTC judge.

ISSUE:

Whether the Naga MTC was correct in issuing Search Warrant

No. 2001-01 for the seizure of the empty Coke bottles from

Pepsi's yard for probable violation of Section 168.3 (c) of the IP

Code.

HELD:

NO.

We clarify at the outset that while we agree with the RTC

decision, our agreement is more in the result than in the

reasons that supported it. The decision is correct in nullifying

the search warrant because it was issued on an invalid

substantive basis - the acts imputed on the respondents do not

violate Section 168.3 (c) of the IP Code. For this reason, we

deny the present petition.

In the context of the present case, the question is whether the

act charged - alleged to be hoarding of empty Coke bottles constitutes an offense under Section 168.3 (c) of the IP Code.

Section 168 in its entirety states:

SECTION 168. Unfair Competition, Rights, Regulation

and Remedies. 168.1. A person who has identified in the mind of the

public the goods he manufactures or deals in, his

business or services from those of others, whether or

not a registered mark is employed, has a property right

in the goodwill of the said goods, business or services

so identified, which will be protected in the same

manner as other property rights.

168.2. Any person who shall employ deception or any

other means contrary to good faith by which he shall

pass off the goods manufactured by him or in which he

deals, or his business, or services for those of the one

having established such goodwill, or who shall commit

any acts calculated to produce said result, shall be

guilty of unfair competition, and shall be subject to an

action therefor.

168.3. In particular, and without in any way limiting the

scope of protection against unfair competition, the

following shall be deemed guilty of unfair competition:

(a) Any person, who is selling his goods and

gives them the general appearance of goods

of another manufacturer or dealer, either as

to the goods themselves or in the wrapping of

the packages in which they are contained, or

the devices or words thereon, or in any other

feature of their appearance, which would be

likely to influence purchasers to believe that

the goods offered are those of a manufacturer

or dealer, other than the actual manufacturer

or dealer, or who otherwise clothes the goods

with such appearance as shall deceive the

public and defraud another of his legitimate

trade, or any subsequent vendor of such

goods or any agent of any vendor engaged in

selling such goods with a like purpose;

(b) Any person who by any artifice, or device,

or who employs any other means calculated

to induce the false belief that such person is

offering the services of another who has

identified such services in the mind of the

public; or

(c) Any person who shall make any false

statement in the course of trade or who shall

commit any other act contrary to good faith of

a nature calculated to discredit the goods,

business or services of another.

168.4. The remedies provided by Sections 156, 157

and 161 shall apply mutatis mutandis. (Sec. 29, R.A.

No. 166a)

From jurisprudence, unfair competition has been defined as the

passing off (or palming off) or attempting to pass off upon the

public the goods or business of one person as the goods or

business of another with the end and probable effect of

deceiving the public. It formulated the "true test" of unfair

competition: whether the acts of defendant are such as are

calculated to deceive the ordinary buyer making his purchases

under the ordinary conditions which prevail in the particular

trade to which the controversy relates. One of the essential

requisites in an action to restrain unfair competition is proof of

fraud; the intent to deceive must be shown before the right to

recover can exist. The advent of the IP Code has not

significantly changed these rulings as they are fully in accord

with what Section 168 of the Code in its entirety provides.

Deception, passing off and fraud upon the pub lic are still the

key elements that must be present for unfair competition to

exist.

The act alleged to violate the petitioner's rights under Section

168.3 (c) is hoarding which we gather to be the collection of the

petitioner's empty bottles so that they can be withdrawn from

circulation and thus impede the circulation of the petitioner's

bottled products. This, according to the petitioner, is an act

contrary to good faith - a conclusion that, if true, is indeed an

unfair act on the part of the respondents. The critical question,

however, is not the intrinsic unfairness of the act of hoarding;

what is critical for purposes of Section 168.3 (c) is to determine

if the hoarding, as charged, "is of a nature calculated to

discredit the goods, business or services" of the petitioner.

We hold that it is not. Hoarding as defined by the petitioner is

not even an act within the contemplation of the IP Code.

Under all the above approaches, we conclude that the

"hoarding" - as defined and charged by the petitioner - does not

fall within the coverage of the IP Code and of Section 168 in

particular. It does not relate to any patent, trademark, trade

name or service mark that the respondents have invaded,

intruded into or used without proper authority from the

petitioner. Nor are the respondents alleged to be fraudulently

"passing off" their products or services as those of the

petitioner. The respondents are not also alleged to be

undertaking any representation or misrepresentation that would

confuse or tend to confuse the goods of the petitioner with

those of the respondents, or vice versa. What in fact the

petitioner alleges is an act foreign to the Code, to the concepts

it embodies and to the acts it regulates; as alleged, hoardi ng

inflicts unfairness by seeking to limit the opposition's sales by

depriving it of the bottles it can use for these sales.

Based on the foregoing, we conclude that the RTC correctly

ruled that the petitioner's search warrant should properly be

quashed for the petitioner's failure to show that the acts imputed

to the respondents do not violate the cited offense. There could

not have been any probable cause to support the issuance of a

search warrant because no crime in the first place was

effectively charged. This conclusion renders unnecessary any

further discussion on whether the search warrant application

properly alleged that the imputed act of holding Coke empties

was in fact a "hoarding" in bad faith aimed to prejudice the

petitioner's operations, or whether the MTC duly complied with

the procedural requirements for the issuance of a search

warrant under Rule 126 of the Rules of Court.

SUPERIOR

COMMERCIAL

ENTERPRISES,

INC.,

vs. KUNNAN ENTERPRISES LTD. AND SPORTS CONCEPT

& DISTRIBUTOR, INC., G.R. No. 169974, April 20, 2010

Facts:

On February 23, 1993, SUPERIOR filed a complaint for

trademark infringement and unfair competition with preliminary

injunction against KUNNAN and SPORTS CONCEPT with the

RTC, docketed as Civil Case No. Q-93014888.

In support of its complaint, SUPERIOR first claimed to be the

owner of the trademarks, trading styles, company names and

business names KENNEX, KENNEX & DEVICE, PRO

KENNEX

and

PRO-KENNEX

(disputed

trademarks). Second, it also asserted its prior use of these

trademarks, presenting as evidence of ownership the Principal

and Supplemental Registrations of these trademarks in its

name. Third, SUPERIOR also alleged that it extensively sold

and advertised sporting goods and products covered by its

trademark registrations. Finally, SUPERIOR presented as

evidence of its ownership of the disputed trademarks the

preambular clause of the Distributorship Agreement dated

October 1, 1982 (Distributorship Agreement) it executed with

KUNNAN, which states:

Whereas, KUNNAN intends to acquire the ownership of

KENNEX trademark registered by the [sic] Superior in the

Philippines. Whereas, the [sic] Superior is desirous of having

been appointed [sic] as the sole distributor by KUNNAN in the

territory of the Philippines. [Emphasis supplied.]

In its defense, KUNNAN disputed SUPERIORs claim of

ownership and maintained that SUPERIOR as mere

distributor from October 6, 1982 until December 31, 1991

fraudulently registered the trademarks in its name. KUNNAN

alleged that it was incorporated in 1972, under the name

KENNEX Sports Corporation for the purpose of manufacturing

and selling sportswear and sports equipment; it commercially

marketed its products in different countries, including the

Philippines since 1972. It created and first used PRO

KENNEX, derived from its original corporate name, as a

distinctive trademark for its products in 1976. KUNNAN also

alleged that it registered the PRO KENNEX trademark not

only in the Philippines but also in 31 other countries, and widely

promoted the KENNEX and PRO KENNEX trademarks

through worldwide advertisements in print media and

sponsorships of known tennis players.

On October 1, 1982, after the expiration of its initial

distributorship agreement with another company, KUNNAN

appointed SUPERIOR as its exclusive distributor in the

Philippines under a Distributorship Agreement whose pertinent

provisions state:

Whereas, KUNNAN intends to acquire ownership of KENNEX

trademark

registered

by

the

Superior

in

the

Philippines. Whereas, the Superior is desirous of having been

appointed [sic] as the sole distributor by KUNNAN in the

territory of the Philippines .

Now, therefore, the parties hereto agree as

follows:

1.

KUNNAN in accordance with this Agreement, will appoint

the sole distributorship right to Superior in the Philippines , and

this Agreement could be renewed with the consent of both

parties upon the time of expiration.

2. The Superior, in accordance with this Agreement, shall

assign the ownership of KENNEX trademark, under the

registration of Patent Certificate No. 4730 dated 23 May 1980 to

KUNNAN on the effects [sic] of its ten (10) years contract of

distributorship, and it is required that the ownership of the said

trademark shall be genuine, complete as a whole and without

any defects.

On December 3, 1991, upon the termination of its

distributorship agreement with SUPERIOR, KUNNAN appointed

SPORTS CONCEPT as its new distributor. Subsequently,

KUNNAN also caused the publication of a Notice and Warning

in the Manila Bulletins January 29, 1993 issue, stating that (1) it

is the owner of the disputed trademarks ; (2) it terminated its

Distributorship Agreement with SUPERIOR; and (3) it appointed

SPORTS CONCEPT as its exclusive distributor. This notice

prompted SUPERIOR to file its Complaint for Infringement of

Trademark and Unfair Competition with Preliminary Injunction

against KUNNAN.

The IPO and CA Rulings

There being sufficient evidence to prove that the PetitionerOpposer (KUNNAN) is the prior user and owner of the

trademark PRO-KENNEX, the consolidated Petitions for

Cancellation

and

the Notices

of Opposition are

herebyGRANTED.

Consequently, the trademark PROKENNEX bearing Registration Nos. 41032, 40326, 39254,

4730, 49998 for the mark PRO-KENNEX issued in favor of

Superior Commercial Enterprises, Inc., herein RespondentRegistrant under the Principal Register and SR No. 6663 are

hereby CANCELLED. Accordingly, trademark application Nos.

84565 and 84566, likewise for the registration of the mark PROKENNEX

are

hereby REJECTED.

It dismissed SUPERIORs Complaint for Infringement of

Trademark and Unfair Competition with Preliminary Injunction

on the ground that SUPERIOR failed to establish by

preponderance of evidence its claim of ownership over the

KENNEX and PRO KENNEX trademarks . The CA found the

Certificates of Principal and Supplemental Registrations and the

whereas clause of the Distributorship Agreement insufficient to

support SUPERIORs claim of ownership over the disputed

trademarks.

The CA stressed that SUPERIORs possession of the

aforementioned Certificates of Principal Registration does not

conclusively establish its ownership of the disputed trademarks

as dominion over trademarks is not acquired by the fact of

registration alone; at best, registration merely raises a

presumption of ownership that can be rebutted by contrary

evidence. The CA further emphasized that the Certificates of

Supplemental Registration issued in SUPERIORs name do not

even enjoy the presumption of ownership accorded to

registration in the principal register; it does not amount to

a prima facie evidence of the validity of registration or of the

registrants exclusive right to use the trademarks in connection

with the goods, business, or services specified in the certificate

ESSO STANDARD EASTERN, INC., petitioner, vs. THE

HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ** and UNITED

CIGARETTE CORPORATION, respondents.

FACTS:

Petitioners Claim:

The complaint alleged that the petitioner had been for many

years engaged in the sale of petroleum products and its

trademark ESSO had acquired a considerable goodwill to such

an extent that the buying public had always taken the trademark

ESSO as equivalent to high quality petroleum products.

Petitioner asserted that the continued use by private respondent

of the same trademark ESSO on its cigarettes was being

carried out for the purpose of deceiving the public as to its

quality and origin to the detriment and disadvantage of its own

products.

Respondents Claim:

In its answer, respondent admitted that it used the

trademark ESSO on its own product of cigarettes, which was

not Identical to those produced and sold by petitioner and

therefore did not in any way infringe on or imitate petitioner's

trademark. Respondent contended that in order that there may

be trademark infringement, it is indispensable that the mark

must be used by one person in connection or competition with

goods of the same kind as the complainant's.

ISSUE:

WHETHER THERE WAS TRADEMARK INFRINGEMENT

From jurisprudence, unfair competition has been defined as the

passing off (or palming off) or attempting to pass off upon the

public of the goods or business of one person as the goods or

business of another with the end and probable effect of

deceiving the public. The essential elements of unfair

competition are (1) confusing similarity in the general

appearance of the goods; and (2) intent to deceive the public

and defraud a competitor.

Jurisprudence also formulated the following true test of unfair

competition: whether the acts of the defendant have the intent

of deceiving or are calculated to deceive the ordinary buyer

making his purchases under the ordinary conditions of the

particular trade to which the controversy relates. One of the

essential requisites in an action to restrain unfair competition is

proof of fraud; the intent to deceive, actual or probable must be

shown before the right to recover can exist.

In the present case, no evidence exists showing that KUNNAN

ever attempted to pass off the goods it sold (i.e. sportswear,

sporting goods and equipment) as those of SUPERIOR. In

addition, there is no evidence of bad faith or fraud imputable to

KUNNAN in using the disputed trademarks. Specifically,

SUPERIOR failed to adduce any evidence to show that

KUNNAN by the above-cited acts intended to deceive the public

as to the identity of the goods sold or of the manufacturer of the

goods sold. In McDonalds Corporation v. L.C. Big Mak Burger,

Inc.,we held that there can be trademark infringement without

unfair competition such as when the infringerdiscloses on the

labels containing the mark that he manufactures the goods,

thus preventing the public from being deceived that the goods

originate from the trademark owner. In this case, no issue of

confusion arises because the same manufactured products are

sold; only the ownership of the trademarks is at issue.

Finally, with the established ruling that KUNNAN is the rightful

owner of the trademarks of the goods that SUPERIOR asserts

are being unfairly sold by KUNNAN under trademarks

registered in SUPERIORs name, the latter is left with no

effective right to make a claim. In other words, with the CAs

final ruling in the Registration Cancellation Case, SUPERIORs

case no longer presents a valid cause of action. For this

reason, the unfair competition aspect of the SUPERIORs case

likewise falls.

HELD:

It is undisputed that the goods on which petitioner uses

the trademark ESSO, petroleum products, and the product of

respondent, cigarettes, are non-competing. But as to whether

trademark infringement exists depends for the most part upon

whether or not the goods are so related that the public may be,

or is actually, deceived and misled that they came from the

same maker or manufacturer.

In the situation before us, the goods are obviously different from

each other with "absolutely no iota of similitude" as stressed in

respondent court's judgment. They are so foreign to each other

as to make it unlikely that purchasers would think that petitioner

is the manufacturer of respondent's goods. The mere fact that

one person has adopted and used a trademark on his goods

does not prevent the adoption and use of the same trademark

by others on unrelated articles of a different kind.

ETEPHA, A.G., petitioner, vs. DIRECTOR OF PATENTS

and

WESTMONT

PHARMACEUTICALS,

INC.,

respondents .

(G.R. No. L-20635, March 31, 1966)

FACTS:

Res pondent Wes tmont Pha rma ceuti ca l s , Inc., a New York

corpora tion, sought registration of trademark "Atussin" placed on i ts

"medicinal preparation of expectorant a ntihistaminic, bronchodilator

s edative, ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) used i n the trea tment of cough".

The tra demark is used exclusively i n the Philippines since Ja nua ry 21,

1959.

Peti ti oner, Etepha, A. G., a Li echtens ti n (pri nci pa l i ty) corpora ti on,

objected claiming tha t i t wi l l be da ma ged beca us e Atus s i n i s s o

confusedly s imila r to i ts Pertus s i n us ed on a prepa ra ti on for the

trea tment of coughs , tha t the buyi ng publ i c wi l l be mi s l ed i nto

bel ievi ng tha t Wes tmont's product i s tha t of peti ti oner's whi ch

a l l egedl y enjoys goodwi l l .

The Di rector of Pa tents ruled tha t the tra dema rk ATUSSIN ma y be

regi stered even though PERTUSSIN had been previ ous l y regi s tered

from the s a me offi ce, hence, thi s a ppea l .

ISSUE: Whethe r or not ATUSSIN ma y be regi s tered?

HELD:

We a re to be gui ded by the rul e tha t the va l i di ty of a ca us e for

i nfri ngement i s predicated upon col ora bl e i mi ta ti on. The phra s e

"col orable i mitation" denotes s uch a "close or i ngenious i mitation a s

to be ca l culated to deceive ordinary persons, or s uch a resembl a nce

to the ori gi na l a s to decei ve a n ordi na ry purcha s er, gi vi ng s uch

a ttention a s a purchaser usually gives, and to cause him to purcha s e

the one s uppos i ng i t to be the other.

A pra cti cal a pproach to the problem of similarity or dissimilari ty i s to

go i nto the whole of the two tra demarks pictured i n their ma nner of

di s play. Inspection should be underta ken from the vi ewpoi nt of a

pros pective buyer. Confusion is likely between trademarks, however,

onl y i f their over-all presentations in a ny of the particulars of s ound,

a ppearance, or meaning are s uch a s would lead the purchasing public

i nto believi ng tha t the products to whi ch the ma rks a re a ppl i ed

ema na ted from the s a me s ource.

We concede the pos s i bi l i ty tha t buyers mi ght be a bl e to obta i n

Pertus sin or Attusin without prescription. When this ha ppens , then

the buyer must be one thoroughly familiar with wha t he i ntends to

get, el se he would not ha ve the temeri ty to a s k for a medi ci ne

s pecifically needed to cure a given ailment. In which ca s e, the more

i mprobable i t will be to palm off one for the other. For a person who

purcha s es wi th open eyes i s ha rdl y the ma n to be decei ved.

On Apri l 21, 1993, the Ma kati RTC denied, for l ack of meri t,

res pondents pra yer for the i s s ua nce of a wri t of prel i mi na ry

i njuncti on.

On Augus t

19,

1993,

res pondents

moti on

for

recons i dera ti on wa s deni ed.

On Februa ry 20, 1995, the CA l i kewi s e di s mi s s ed

res pondents peti ti on for revi ew on certi ora ri .

After the tri a l on the meri ts , however, the Ma ka ti RTC,

on November 26, 1998, hel d peti ti oners l i a bl e for, perma nentl y

enjoi ned from commi tti ng tra dema rk i nfri ngement a nd unfa i r

competi ti on wi th res pect to the GALLO tra dema rk.

On a ppeal, the CA a ffirmed the Makati RTCs deci s i on a nd

s ubs equentl y deni ed peti ti oners moti on for recons i dera ti on.

For the reasons gi ven, the a ppea l ed deci s i on of the res pondent

Di rector of Patents gi ving due cours e to the a ppl i ca ti on for the

regi stration of tra demark ATTUSIN is hereby a ffi rmed. Cos t a ga i ns t

peti ti oner. So ordered.

ISSUE:

Whether GALLO ci garettes and GALLO wines were i dentical,

MIGHTY CORPORATION and LA CAMPANA

FABRICA DE TABACO, INC. vs. E.J. GALLO WINERY

and THE ANDRESONS GROUP, INC.

s i mi l a r or rel a ted goods for the rea s on a l one tha t they were

purportedl y forms of vi ce.

HELD:

FACTS:

Wi nes and ci garettes are not identical, s i mi l a r, competi ng or

rel a ted goods .

On Ma rch 12, 1993, res pondents sued petitioners i n the RTCMa ka ti for tra dema rk a nd tra de na me i nfri ngement a nd unfa i r

competition, wi th a prayer for damages a nd preli mi na ry i njuncti on.

In resolving whether goods are related, s evera l fa ctors come

i nto pl a y:

They cl aimed that petitioners adopted the Gallo tradema rk to

the business (and i ts location) to whi ch the goods bel ong

ri de on Gallo Wi nerys a nd Gallo a nd Ernest & Julio Gallo tra demarks

the cl a s s of product to whi ch the good bel ong

es tablis hed reputa ti on a nd popul a ri ty, thus ca us i ng confus i on,

the products quality, quantity, or s ize, including the nature

deception a nd mistake on the part of the purchasing public who ha d

of the pa cka ge, wra pper or conta i ner

a l ways associated Gallo and Ernest and Julio & Gallo tra demarks with

the na ture a nd cos t of the a rti cl es

Ga l l o Wi nerys wi nes .

the descriptive properties, physical attributes or es s enti a l

cha ra cteristics with reference to thei r form, compos i ti on,

In their answer, petitioners alleged, among other a ffi rma ti ve

texture or qua l i ty

defenses that: petitioners Gallo cigarettes a nd Ga l l o Wi nerys wi ne

the purpos e of the goods

were tota l l y unrel a ted products . To wi t:

whether the a rticle is bought for i mmediate cons umpti on,

1. Ga l lo Winerys GALLO tra demark registration certificates covered

wi nes onl y, a nd not ci ga rettes ;

2. GALLO ci ga rettes a nd GALLO wi nes were s old through di fferent

tha t i s , da y-to-da y hous ehol d i tems

the fi el d of ma nufa cture

the conditions under which the a rticle is usually purcha s ed

cha nnel s of tra de;

3. the ta rget market of Gallo Wi nerys wi nes wa s the mi ddl e or

hi gh-income bracket while Gallo ci garette buyers were fa rmers ,

a nd

the a rti cles of the tra de through which the goods flow, how

they a re di s tri buted, ma rketed, di s pl a yed a nd s ol d.

fi s hermen, l a borers a nd other l ow-i ncome workers ;

4. the domina nt fea ture of the Ga l l o ci ga rette wa s the roos ter

devi ce wi th the ma nufa cturers na me cl ea rl y i ndi ca ted a s

MIGHTY CORPORATION, whi l e i n the ca s e of Ga l l o Wi nerys

wi nes, i t was the full names of the founders -owners ERNEST &

JULIO GALLO or jus t thei r s urna me GALLO;

The tes t of fra udulent simulation is to the likelihood of the

deception of some persons i n s ome mea s ure a cqua i nted wi th a n

es tablished design and desirous of purchas i ng the commodi ty wi th

whi ch that design has been associated. The simulation, in order to be

objectionable, must be as a ppea rs l i kel y to mi s l ea d the ordi na ry

i ntelligent buyer who has a need to s upply a nd i s fa mi l i a r wi th the

a rti cl e tha t he s eeks to purcha s e.

broa d, the inevitable conclusion is that i t wa s done del i bera tel y to

decei ve.

The petitioners a re not liable for tra demark i nfri ngement,

unfa i r competi ti on or da ma ges .

WHEREFORE, petition is granted.

DEL MONTE CORPORATION and PHILIPPINE

PACKING CORPORATION vs. COURT OF APPEALS

and

SUNSHINE

SAUCE

MANUFACTURING

INDUSTRIES

G.R. No. L-78325 Ja nua ry 25, 1990

FACTS: Peti ti oner Del Monte Corpora ti on (Del Monte), through i ts

l oca l distributor a nd manufacturer, PhilPack filed an i nfringement of

copyri ght compl a i nt a ga i ns t res pondent Suns hi ne Sa uce

Ma nufacturing Industries (SSMI), also a ma ker of ca ts up a nd other

ki tchen sauces. In i ts compla i nt, Del Monte a l l eged tha t SSMI a re

us i ng bottl es a nd l ogos i denti ca l to the peti ti oner, to whi ch i s

decei vi ng a nd mi s l ea di ng to the publ i c.

In i ts answer, Sunshine a l l eged tha t i t ha d cea s ed to us e the Del

Monte bottle and that its l ogo was substanti a l l y di fferent from the

Del Monte l ogo a nd woul d not confus e the buyi ng publ i c to the

detri ment of the peti ti oners .

The Regional Trial Court of Makati dismissed the compl a i nt. It hel d

tha t there were s ubs ta nti a l di fferences between the l ogos or

tra demarks of the parties nor on the conti nued us e of Del Monte

bottl es. The decision was affirmed i n toto by the Court of Appea l s .

ISSUE: Whether or not SSMI commi tted i nfri ngement a ga i ns t Del

Monte i n the us e of i ts l ogos a nd bottl es .

HELD: Yes . In determining whether two trademarks a re confus i ngl y

s i mi l a r, the two ma rks i n thei r enti rety a s they a ppea r i n the

res pective l abels mus t be cons i dered i n rel a ti on to the goods to

whi ch they a re a ttached; the di s cerni ng eye of the obs erver mus t

focus not onl y on the precogni za nt words but a l s o on the other

fea tures appearing on both l abel s . It ha s been correctl y hel d tha t

s i de-by-s i de compa ri s on i s not the fi na l tes t of s i mi l a ri ty. In

determini ng whether a tra dema rk ha s been i nfri nged, we mus t

cons i der the ma rk a s a whol e a nd not a s di s s ected.

The Court i s a greed that are i ndeed distinctions, but similarities holds

a grea ter wei ght i n thi s ca s e. The Suns hi ne l a bel i s a col ora bl e

i mi tation of the Del Monte tra demark. What is undeniable is the fa ct

tha t when a ma nufacturer prepares to package hi s product, he ha s

before him a boundless choice of words, phrases, colors a nd s ymbols

s ufficient to distinguish his product from the others. Sunshine chos e,

wi thout a reasonable explanation, to use the s ame colors a nd l etters

a s those used by Del Monte though the field of its s el ecti on wa s s o

Wi th regard to the bottle use, Sunshi ne des pi te the ma ny choi ces

a va ilable to i t a nd notwi ths ta ndi ng tha t the ca uti on "Del Monte

Corpora tion, Not to be Refilled" was embos s ed on the bottl e, s ti l l

opted to us e the peti ti oners ' bottl e to ma rket a product whi ch

Phi l pack also produces. This cl early s hows the pri va te res pondent's

ba d faith and its intention to ca pitalize on the l atter's reputation a nd

goodwi l l a nd pa s s off i ts own produ ct a s tha t of Del Monte.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- GARCIA vs. CA Ruling on Contract to Sell RescissionDokument2 SeitenGARCIA vs. CA Ruling on Contract to Sell RescissionLoi Molina Lopena100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Pre-Trial ReportDokument10 SeitenPre-Trial ReportAldrin Aguas100% (1)

- NLRC Affirms Manager's Suspension for Sexual HarassmentDokument3 SeitenNLRC Affirms Manager's Suspension for Sexual HarassmentSylina AlcazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agency Digests Set B and CDokument6 SeitenAgency Digests Set B and CAlbert BantanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air Transpo DigestsDokument6 SeitenAir Transpo DigestsMis Dee100% (1)

- Transpo DigestDokument2 SeitenTranspo DigestMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue V Manila Bankers DigestDokument1 SeiteCommissioner of Internal Revenue V Manila Bankers DigestMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue V Manila Bankers DigestDokument1 SeiteCommissioner of Internal Revenue V Manila Bankers DigestMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue V Manila Bankers DigestDokument1 SeiteCommissioner of Internal Revenue V Manila Bankers DigestMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Land Partition Case Between Heirs of Federico Valdez Sr. and Widow of Federico Valdez JrDokument2 SeitenLand Partition Case Between Heirs of Federico Valdez Sr. and Widow of Federico Valdez JrMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insurance Dispute Over Policy CoverageDokument4 SeitenInsurance Dispute Over Policy CoverageMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Land dispute in BulacanDokument2 SeitenLand dispute in BulacanCherry Rhose Cureg100% (1)

- Kiel vs. Estate of SabertDokument1 SeiteKiel vs. Estate of SabertMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Centennial vs. Dela Cruz (2008)Dokument1 SeiteCentennial vs. Dela Cruz (2008)Mis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Centennial vs. Dela Cruz (2008)Dokument1 SeiteCentennial vs. Dela Cruz (2008)Mis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mike Bobo Employment ContractDokument15 SeitenMike Bobo Employment ContractHKMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affirmative Second SpeakerDokument2 SeitenAffirmative Second SpeakerAnonymous B0hmWBT82% (11)

- Icasiano v. Icasiano Digest G.R. No. L-18979 June 30, 1964 Signature To A Page Is Sufficient To Deny Probate of The WillDokument1 SeiteIcasiano v. Icasiano Digest G.R. No. L-18979 June 30, 1964 Signature To A Page Is Sufficient To Deny Probate of The WillMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- de La Cruz V Northern Theatrial Enterprises: AGENCY (Obieta) DIGESTS by Sham ZaragozaDokument8 Seitende La Cruz V Northern Theatrial Enterprises: AGENCY (Obieta) DIGESTS by Sham ZaragozaMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- People of The Philippines vs. VerdadDokument1 SeitePeople of The Philippines vs. VerdadEthan KurbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monarch Insurance Vs CADokument3 SeitenMonarch Insurance Vs CAMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sinaon vs. Soroñgon, 136 SCRA 407 (1985)Dokument1 SeiteSinaon vs. Soroñgon, 136 SCRA 407 (1985)Mis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Succession DigestsDokument3 SeitenSuccession DigestsMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict of Laws 1st Set DigestDokument2 SeitenConflict of Laws 1st Set DigestMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Batangas City Business Tax Exemption for Pipeline OperatorDokument7 SeitenBatangas City Business Tax Exemption for Pipeline OperatorRocky CadizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax DigestsDokument3 SeitenTax DigestsMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agency Digests Set B and CDokument7 SeitenAgency Digests Set B and CMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gutierrez Hermanos V OrenseDokument1 SeiteGutierrez Hermanos V OrenseMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax DigestsDokument3 SeitenTax DigestsMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transportation Law - Air Transpo DigestsDokument2 SeitenTransportation Law - Air Transpo DigestsMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Martinez Vs Ong PoDokument3 SeitenMartinez Vs Ong PoLeslie LernerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eastern Shipping Lines V IacDokument2 SeitenEastern Shipping Lines V IacMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Batangas City Business Tax Exemption for Pipeline OperatorDokument7 SeitenBatangas City Business Tax Exemption for Pipeline OperatorRocky CadizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sun Life V CADokument1 SeiteSun Life V CAMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insurance Full Text 2nd SetDokument14 SeitenInsurance Full Text 2nd SetMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- PINEDA V CA Full Text CaseDokument12 SeitenPINEDA V CA Full Text CaseMis DeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCLAT OrderDokument32 SeitenNCLAT OrderShiva Rama Krishna BeharaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19bce0696 VL2021220701671 Ast02Dokument7 Seiten19bce0696 VL2021220701671 Ast02Parijat NiyogyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Ethos & Business Ethics End Term PaperDokument12 SeitenIndian Ethos & Business Ethics End Term Paperkuntal bajpayeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Awe SampleDokument12 SeitenAwe SamplerichmondNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bulk Sms Service Provider in India - Latest Updated System - Sending BULK SMS in IndiaDokument4 SeitenBulk Sms Service Provider in India - Latest Updated System - Sending BULK SMS in IndiaSsd IndiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Declaration of NullityDokument3 SeitenEffects of Declaration of NullityJacqueline PaulinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Camellia Feat Nanahira Can I Friend You On Bassbook Lol Bassline Yatteru LOLDokument6 SeitenCamellia Feat Nanahira Can I Friend You On Bassbook Lol Bassline Yatteru LOLCarmelo RestivoNoch keine Bewertungen

- NOUN VERB ADJECTIVE ADVERB PREPOSITION CONJUNCTION 2000KATADokument30 SeitenNOUN VERB ADJECTIVE ADVERB PREPOSITION CONJUNCTION 2000KATAazadkumarreddy100% (1)

- Answer To Exercises-Capital BudgetingDokument18 SeitenAnswer To Exercises-Capital BudgetingAlleuor Quimno50% (2)

- Recognition and Moral Obligation (Makale, Honneth)Dokument21 SeitenRecognition and Moral Obligation (Makale, Honneth)Berk Özcangiller100% (1)

- Red Cross Youth and Sinior CouncilDokument9 SeitenRed Cross Youth and Sinior CouncilJay-Ar ValenzuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Religions Chart - KeyDokument2 SeitenComparative Religions Chart - Keyapi-440272030Noch keine Bewertungen

- Testbank Fim Từ A Đến Z Học Đi Quyên Sap Thi Final Roi Quyên chap 3Dokument18 SeitenTestbank Fim Từ A Đến Z Học Đi Quyên Sap Thi Final Roi Quyên chap 3s3932168Noch keine Bewertungen

- Court Upholds Petitioner's Right to Repurchase LandDokument176 SeitenCourt Upholds Petitioner's Right to Repurchase LandLuriza SamaylaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jexpo Merit 2022Dokument1.125 SeitenJexpo Merit 2022Sayon SarkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- ULAB Midterm Exam Business Communication CourseDokument5 SeitenULAB Midterm Exam Business Communication CourseKh SwononNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bharat Dalpat Patel Vs Russi Jal DorabjeeDokument4 SeitenBharat Dalpat Patel Vs Russi Jal DorabjeeExtreme TronersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Examination of Conscience (For Adults) Catholic-Pages - ComDokument4 SeitenExamination of Conscience (For Adults) Catholic-Pages - ComrbrunetrrNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Proposal Made By: Shashwat Pratyush Roll No: 1761 Class: B.A.LL.B. (Hons.) Semester: 5Dokument30 SeitenA Proposal Made By: Shashwat Pratyush Roll No: 1761 Class: B.A.LL.B. (Hons.) Semester: 5Shashwat PratyushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of Liquidity and Capital AdequacyDokument21 SeitenImportance of Liquidity and Capital AdequacyGodsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH08 PDFDokument25 SeitenCH08 PDFpestaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPD Daily Incident Report 6/4/21Dokument8 SeitenRPD Daily Incident Report 6/4/21inforumdocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPPTChap 006Dokument16 SeitenSPPTChap 006iqraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Format of Writ Petition To High Court Under Article 226Dokument3 SeitenFormat of Writ Petition To High Court Under Article 226Faiz MalhiNoch keine Bewertungen