Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Review of Zafar and The Raj

Hochgeladen von

Manu V. DevadevanOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review of Zafar and The Raj

Hochgeladen von

Manu V. DevadevanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

B.

SURENDRA RAO

Amar Farooqui

Zafar and the Raj: Anglo-Mughal Delhi, c.1800-1850

Primus Books, New Delhi, 2013

B. SURENDRA RAO

The subject of this book is not new. Scholars like Syed Mahdi

Husain, G.D. Khosla, Percival Spear, William Dalrymple and others have

told the story of the Last Mughal. Sometimes it has been told as a melancholy epilogue of a great empire, as a relic of wretchedness to which it

had reduced itself, and occasionally to condole the life of an unlikely

national hero of the first national war of independence. To most British

historians the sign of this wretched denouement of the Mughal Empire

could be seen even as the nineteenth century dawned. As Lane-Poole

wrote, When Lord Lake entered Delhi in 1803, he was shown a miserable blind old imbecile, sitting under a tattered canopy. It was Shah-Alam,

King of the World, but a captive of the Marathas, a wretched travesty of

the Emperor of India. The British General gravely saluted the shadow of

the Great Mogul.... The ludibrium rerum humanarum was never more

pathetically played. No curtain ever dropped on a more woeful tragedy.

The story of the Mughals in the next fifty years or so is shown in the

colonial writings as petty tales of whimpering shadows, sordid palace intrigues and the occasion for the British sweep away the wretched irrelevance of the doddering old fool Bahadur Shah Zafar and his dynasty in

1858. This picture has been critically interrogated by Amar Farooqui in

Zafar and the Raj and a new portrait of the Anglo-Mughal Delhi has been

superbly drawn, not so much to vindicate Zafar or arrange for him a new

coronation in history but to re-locate him within the framework of colonial rule. The book is much more than a biography of Bahadur Zafar; it is a

sensitive retrieval of a world in which the swaggering colonial rulers were yet contending against the reality of the Mughal imperial name, which

still seemed to have by its side its own apparition of reputation and power

which the British found curiously hard to exorcise.

The book is particularly significant in the context of the need to

understand the anomalous nature of the colonial state which the merchant

entrepreneurs of the East India Company were creating in India. For all

BOOK REVIEWS

172

B. SURENDRA RAO

its successful subterfuges and military conquests the Company was aware

of its foreignness and the illegitimacy of its governance. It was also

aware of the halo of legitimacy which the Mughal rule enjoyed even after

its imperial presence in India had been reduced to a fiction or caricature

by the events of 1759-1761. The Treaty of Allahabad had affirmed it.

Amar Farooqui shows how, contrary to the derisive prose in which the

British sought to describe them, the reigns of Shah Alam II (1759-1806)

and Akbar II (1806-1837) marked a break from some of the unsavoury

features of the reigns of their immediate predecessors from Jahandar

Shah to Alamgir II. In fact, though their empire had shrunk ludicrously to

a tenuous control and nominal management of the locality of Delhi, and

the rulers continued to appeal for the restoration of the peshkash which

the Company reneged on, they could yet effectively draw upon the name

of the Mughal as social and cultural capital. Shah Alam, for example, had

meticulously paid attention to ceremonial and court ritual to gain respect

due to royalty, his disability of blindness notwithstanding. Akbar II and

his son, Bahadur Shah, scrupulously adhered to the ways of Shah Alam

to retain the useful halo of Mughal dignity. Some of them even declined

to receive the Governors-General at their Court, as it would have risked

transgressions to court protocol and ceremonies. Akbar Shah did it to

Lord Hastings in 1814, to William Bentinck in 1831 and Bahadur Shah to

Lord Auckland in 1838. In fact, when the Resident, Francis Hawkins,

made some trivial departures from court etiquette the Mughal Court was

able to secure his dismissal in 1830. For all the pecuniary difficulties and

insults that the Mughal rulers faced or their dependence on the Company

to decide on matters of inheritance and succession, the name of the

Mughal yet carried a halo, which Amar Farooqui rightly points out, beckoned the mutinous sepoys to Delhi in May 1857.

Though the empire of the Mughals had eerily vanished into the

pages of history, the imperial palace in the Delhi Red Fort had retained

the sanctity which the British too, ostensibly, respected. Amar Farooqui

shows how in this city within city the Emperor still mattered, his writ still

ran and he was still the hub around which things seemed to move. The

palace was closely integrated with the social and cultural life of Delhi,

and the Emperors presence extended beyond his palace, to his retreat at

173

BOOK REVIEWS

B. SURENDRA RAO

the Qutb, the Jama Masjid and the villages around the city. The inhabitants of Delhi turned to him spontaneously for redressal of grievances

and at least as someone who could intercede with the British. It was as if

the de jure, as distinct from the de facto, authority of the Mughal emperoremperor sans empire yet mattered. Personally too, Bahadur Shah

Zafar presided over a vibrant literary world and the coming of age of

Urdu as a literary language, which produced such luminaries as Mirza

Ghalib, Momin Khan Momin and Sheik Ibrahim Zauq. Zafar was first

mentored by Shah Nasir and later by Zauq who oversaw the publication

of the Emperors verse. Muhammad Husain Azad, in his influential history of Urdu poetry, Abe-e Hayat (1880), observed that Zafars half-baked

compositions were perfected by Zauq, which is no flattering commentary

on Zafars poetic skill. But that seems to be a travesty of truth. Azad was

himself a disciple of Zauq, and he was apparently too eager to enhance

the stature of his ustad by attributing the authorship of Zafars poems to

him. After Zauqs death in 1854, Zafar became particularly close to Ghalib. Interestingly, perhaps the greatest-ever Urdu poet was commissioned

to write the history of the Timurids in Persian prose. He was supplied

with summaries or selections of histories available in the royal library,

prepared under the supervision of Ahsanullah Khan. Ghalib made it very

clear that he was practising the craft of the litterateur and not that of the

historian.... That Bahadur Shah should have commissioned such a work

reveals his anxiety about his place in history.... [I]t was insufficient that

he should be known to posterity just as a poet. The reality of colonial rule

precluded his being projected as an illustrious monarch. What the proposed history could do was to record that he belonged to a great lineage

whose traditions...he had done his best to preserve. (p. 120) Though

Ghalib lost interest in the history project, he retained connection with the

court. He hated the drudgery of routine attendance in the court, but was

persuaded to persist because of the assurance of some regular income to

the otherwise impecunious state which the literary celebrity was always

in. Besides, Zafar and Ghalib seemed to genuinely enjoy each others

company. Bahadur Shahs reign had also seen the experiment, at Delhi

College, of imparting knowledge of modern science and mathematics

through the medium of Urdu. It had such eminent scholars like Master

BOOK REVIEWS

174

B. SURENDRA RAO

Ram Chandra, Sadiqur Rahman Kidwai and Sadruddin Khan Azurda,

though this alternative path to modernity was historically doomed due to

colonial rule. But around people like Azurda gravitated the best of

intellectuals and scholars like Ghalib and Syed Ahmed Khan.

The Revolt of 1857 turned out to be both a tempting opportunity

and a grim tragedy for the Last Mughal. Amar Farooqui rejects the view

that the Meerut sepoys were nave and acting impulsively when they rushed to Delhi to make a leader out of a pathetic ghost of Mughal royalty.

He argues that this decision of the sepoys affirms that the illegitimacy of

the colonial state had to be projected before it was overthrown and that it

could be done only be acknowledging the legitimacy of the Mughal rule.

In fact, the Revolt of 1857 acquired a definitive political ideology when

the sepoys declared their allegiance to the Mughal rule. Zafar had no idea

of the events at Meerut or the plans of the sepoys, but he had to make his

choice when they did arrive in Delhi. That he chose to reprimand the

sepoys and yet accepted the leadership offered to him while the British

still controlled Delhi shows that he was making a statement about where

he stood in history (p. 145). Amar Farooqui points out that the court of

administration of the brief sepoy regime in Delhi, with its definite

framework and procedures, throws a hint at the new state in its embryonic form; it also did contain seeds of modern democracy. He also

suggests that the roots of the court of administration experiment lay in the

informal soldiers councils within units of the Companys army which in

the pre-revolt period had been forums for deliberating upon various

issues concerning the sepoys. (p. 148) But in the absence of a nationalist

vocabulary, the ideologues of the revolt clothed their programme of anticolonial resistance in religious rhetoric. (p. 152)

But the colonial rulers seemed to know better. If Bahadur Shah

Zafar was keen to preserve and harness the name of the Mughal, the first

thing the British did after recovering Delhi was to erase the name of the

Mughal. Imprisoning of Bahadur Shah, Hodson shooting down some

Mughal princes at Humayuns tomb and the sham trial before the Last

Mughal and his family were sent to their wretched exile in Burma were

all testimonies to the British anxieties and their manifest desperation to

do away with what was left of the Mughal. That the trial of the Mughal

175

BOOK REVIEWS

B. SURENDRA RAO

emperor was held in his own palace was particularly significant both for

its wicked cynicism and political message it was meant to convey. The

physical removal of the emperor from the mainland India was of a piece

with the British policy of delegitimizing the Mughals. Even the presence

of the exiled royal family in Rangoon was hidden from the gaze of the

local inhabitants. Even after the Last Mughal died in 1862, the colonial

state was keen to place a thick veil of cynical de-recognition over members of his family till their melancholy death, Jawan Bakht in 1884, Zinat

Mahal in 1886 and Shah Zamani Begam in 1899. Even the lesser princes

suffered a hostile neglect.

Zafar and the Raj shows that contrary to the imagesstrongly

tattooed on colonial historiographyof the British saying the extreme

unction to an effete and dying Mughal royalty, the Mughal name and

heritage carried a precious and peculiarly powerful source of legitimacy

the British had to contend with. Though without an empire, the Last

Mughal was yet a Mughal. The British could say with an unconcealed

sneer, What is in the name? but they knew that the name indeed mattered. It seemed to mock at their illegitimacy. Zafar too was too aware of

it, however nervously; and he did everything to preserve his name and the

legitimacy it conferred. The British response to it during the climacteric

days of the Great Revolt bears testimony to the uneasy claims of the

colonial state over legitimacy it did not possess and which it could grab

only if they could do away with the name and vestiges of the Mughal

rule. Decency and scruples should not come in the way. The book makes

compelling reading and goads us to take a fresh look at the Last Mughal.

(The reviewer was formerly Professor, Department of History, Mangalore University, Mangalagangothri.)

BOOK REVIEWS

176

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 13th Century NobilityDokument7 Seiten13th Century NobilityKrishnapriya D JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sir Syed Ahmed KhanDokument3 SeitenSir Syed Ahmed KhanAngel Angel100% (1)

- Building Histories: The Archival and Affective Lives of Five Monuments in Modern DelhiVon EverandBuilding Histories: The Archival and Affective Lives of Five Monuments in Modern DelhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Study of the Novels: Of Rokeya Shakwat Hossain Zeenuth Futehally Iqbalunnisa Hussain Tara Ali Baig Attia HosainVon EverandA Critical Study of the Novels: Of Rokeya Shakwat Hossain Zeenuth Futehally Iqbalunnisa Hussain Tara Ali Baig Attia HosainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bombay Cinema's Islamicate HistoriesVon EverandBombay Cinema's Islamicate HistoriesIra BhaskarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Loves of Krishna: In Indian Painting and Poetry (Illustrated)Von EverandThe Loves of Krishna: In Indian Painting and Poetry (Illustrated)Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Great War: Indian Writings on the First World WarVon EverandThe Great War: Indian Writings on the First World WarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legends of People, Myths of State: Violence, Intolerance, and Political Culture in Sri Lanka and AustraliaVon EverandLegends of People, Myths of State: Violence, Intolerance, and Political Culture in Sri Lanka and AustraliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Siege Of Lucknow: A Diary [Illustrated Edition]Von EverandThe Siege Of Lucknow: A Diary [Illustrated Edition]Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Art and ArchitectureDokument7 SeitenIndian Art and ArchitectureSonia KhileriNoch keine Bewertungen

- History Of The Indian Mutiny Of 1857-8 – Vol. III [Illustrated Edition]Von EverandHistory Of The Indian Mutiny Of 1857-8 – Vol. III [Illustrated Edition]Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Philosophy of Tipra: A Discussion on Religion and MoralityVon EverandThe Philosophy of Tipra: A Discussion on Religion and MoralityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allegory and The Imperial Image A ComparDokument79 SeitenAllegory and The Imperial Image A ComparJezabel StrameliniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Book IVon EverandThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Book INoch keine Bewertungen

- Akbars Religious PolicyDokument5 SeitenAkbars Religious Policysatya dewanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Field Notes from a Waterborne Land: Bengal Beyond the BhadralokVon EverandField Notes from a Waterborne Land: Bengal Beyond the BhadralokNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Elephant Gates: Vibrant Reflections of Life, Family, and Tradition in Sri LankaVon EverandThe Elephant Gates: Vibrant Reflections of Life, Family, and Tradition in Sri LankaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relief of Chitral [Illustrated Edition]Von EverandThe Relief of Chitral [Illustrated Edition]Noch keine Bewertungen

- ORIC03Dokument9 SeitenORIC03meenusarohaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Classic Collection of Mahatma Gandhi. Illustrated: A Guide to Health, Freedom's Battle, The Wheel of Fortune, My Experiments With TruthVon EverandThe Classic Collection of Mahatma Gandhi. Illustrated: A Guide to Health, Freedom's Battle, The Wheel of Fortune, My Experiments With TruthNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2009, K. Sharma, A Visit To The Mughal Harem Lives of Royal WomenDokument16 Seiten2009, K. Sharma, A Visit To The Mughal Harem Lives of Royal Womenhistory 2B100% (1)

- Enlightenment in the Colony: The Jewish Question and the Crisis of Postcolonial CultureVon EverandEnlightenment in the Colony: The Jewish Question and the Crisis of Postcolonial CultureBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- A Study Guide for William Shakespeare's "The Merry Wives of Windsor"Von EverandA Study Guide for William Shakespeare's "The Merry Wives of Windsor"Noch keine Bewertungen

- Delhi Through The Ages 1st Year in English AfcemkDokument34 SeitenDelhi Through The Ages 1st Year in English Afcemkanushkac537Noch keine Bewertungen

- Taj Mahal Inscriptions and CalligraphiesDokument4 SeitenTaj Mahal Inscriptions and CalligraphiesHasan Khan100% (1)

- The Indian Emperor: "Boldness is a mask for fear, however great."Von EverandThe Indian Emperor: "Boldness is a mask for fear, however great."Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indian NovelDokument41 SeitenIndian NovelGurjot SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flora Annie Steel: A Critical Study of an Unconventional MemsahibVon EverandFlora Annie Steel: A Critical Study of an Unconventional MemsahibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recent Trends in Indian English NovelsDokument3 SeitenRecent Trends in Indian English Novelsbibhudatta dash100% (1)

- Bege 108 PDFDokument6 SeitenBege 108 PDFFirdosh Khan86% (7)

- Different Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMDokument8 SeitenDifferent Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMAditya ChourasiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conquest and Community: The Afterlife of Warrior Saint Ghazi MiyanVon EverandConquest and Community: The Afterlife of Warrior Saint Ghazi MiyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Options Basics 01Dokument52 SeitenOptions Basics 01sam2004Noch keine Bewertungen

- Meena Kandasamy BiographyDokument2 SeitenMeena Kandasamy BiographyDevidas KrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rise of Absolutism, NotesDokument5 SeitenThe Rise of Absolutism, NotesSiesmicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delhi Sultanate For All Competitive ExamsDokument21 SeitenDelhi Sultanate For All Competitive ExamsVijay JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kiran Kumari. 951Dokument10 SeitenKiran Kumari. 951NeelamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prabhu PDFDokument47 SeitenPrabhu PDFSubi100% (1)

- Biblio Review..BhimayanaDokument2 SeitenBiblio Review..BhimayanaKamala OinamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labour During Mughal India - Rosalind O HanlonDokument36 SeitenLabour During Mughal India - Rosalind O HanlonArya MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- PitrubimbagaluDokument4 SeitenPitrubimbagaluManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bhashe Emba PramanaDokument5 SeitenBhashe Emba PramanaManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Krishna KalebaraDokument5 SeitenKrishna KalebaraManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smriti Emba MoolyaDokument3 SeitenSmriti Emba MoolyaManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smriti Emba MoolyaDokument3 SeitenSmriti Emba MoolyaManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MetamorphasisDokument5 SeitenMetamorphasisManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ramabibha of Arjuna DasaDokument123 SeitenThe Ramabibha of Arjuna DasaManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bhavanirmiti Mattu RoopanirmitiDokument3 SeitenBhavanirmiti Mattu RoopanirmitiManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ekanthate Emba VargaprajneDokument3 SeitenEkanthate Emba VargaprajneManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bhagavadgita of Balaram DasDokument38 SeitenBhagavadgita of Balaram DasManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uáf À Éäêaiàä Ëazàaiàäð ( Àä Àä . Zéã Àzéã À Ï)Dokument6 SeitenUáf À Éäêaiàä Ëazàaiàäð ( Àä Àä . Zéã Àzéã À Ï)Manu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Reassessment of The Origin of The Jagannath Cult of Puri PDFDokument9 SeitenA Reassessment of The Origin of The Jagannath Cult of Puri PDFManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Passe On Somanathapura - Review of S.Dokument2 SeitenA Passe On Somanathapura - Review of S.Manu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Units of TimeDokument1 SeiteIndian Units of TimeManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problems in Reconstructing The Social History of Buddhism in Orissa PDFDokument6 SeitenProblems in Reconstructing The Social History of Buddhism in Orissa PDFManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 73rd AmendmentDokument8 Seiten73rd AmendmentManu V. DevadevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kalinga and The Transformation of AsokaDokument6 SeitenKalinga and The Transformation of Asokamahaparva5874Noch keine Bewertungen

- Historical Significance of 26th JanuaryDokument87 SeitenHistorical Significance of 26th JanuarySoumya Lagnajeet PandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise 1 Dialogues-Topcis PDFDokument1 SeiteExercise 1 Dialogues-Topcis PDFmenchanrethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrega Tarjetas BienestarDokument48 SeitenEntrega Tarjetas Bienestarmelody velezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mohak Meaning in Urdu - Google SearchDokument1 SeiteMohak Meaning in Urdu - Google SearchShaheryar AsgharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suffering If God Is Good WhyDokument2 SeitenSuffering If God Is Good WhykoinoniabcnNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Filipino National Artists in Theater and FilmDokument11 Seiten6 Filipino National Artists in Theater and FilmAnna Jane Catubag57% (21)

- The Vine and The Branches - Federico SuarezDokument80 SeitenThe Vine and The Branches - Federico SuarezAries MatibagNoch keine Bewertungen

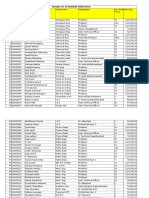

- Employee Remunerations With Pay Scale - 2021 - 22Dokument46 SeitenEmployee Remunerations With Pay Scale - 2021 - 22adityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mauryan Empire - PDF 16Dokument3 SeitenMauryan Empire - PDF 16chirayilrichardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ausamapta Atmajiboni by Sheikh Mujibur RahmanDokument337 SeitenAusamapta Atmajiboni by Sheikh Mujibur RahmansagarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter For Status of LDA Approval (Sahir Associate) March 1, 2021 With List of MembersDokument8 SeitenLetter For Status of LDA Approval (Sahir Associate) March 1, 2021 With List of MembersAnwar ZafarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tico Tico No Fubá-ViolinoDokument1 SeiteTico Tico No Fubá-ViolinoPedro Moreira MagalhãesNoch keine Bewertungen

- MPL 10th National School Chess Championships 2022Dokument4 SeitenMPL 10th National School Chess Championships 2022S. KanishkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bernard A. Cook Belgium A History-Peter Lang Publishing (2004) PDFDokument224 SeitenBernard A. Cook Belgium A History-Peter Lang Publishing (2004) PDFhugosuppo@mac.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Qi Men Dun JiaDokument18 SeitenIntroduction To Qi Men Dun Jiayingyang.dragon5447100% (7)

- AGS Mission ReportDokument8 SeitenAGS Mission ReportLalhlimpuiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning About IGOROTSDokument7 SeitenLearning About IGOROTSSunette Mennie V. ElediaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument2 SeitenAnnotated Bibliographyapi-308491090Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wipro FinalDokument11 SeitenWipro FinalmegaspiceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christmas Inbuatsaihna Tha BerDokument4 SeitenChristmas Inbuatsaihna Tha BerPascal ChhakchhuakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grpup chấtDokument66 SeitenGrpup chấtVũ Hoàng LongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Encounter With The WestDokument33 SeitenEncounter With The WestRoxanne Postrano De VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christian Soldier MedleyDokument1 SeiteChristian Soldier MedleyJhon Lester Magarso100% (1)

- Seguimiento Academico GeiderDokument49 SeitenSeguimiento Academico Geidergeider peñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manpower - Recruitment - Details - Upload - CSCDokument15 SeitenManpower - Recruitment - Details - Upload - CSCrohitsharma3oneNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSE 2013 General Merit ListDokument55 SeitenCSE 2013 General Merit Listspirate89Noch keine Bewertungen

- DENAH - DUDUK - SEAT - 2 - 3 - 59 - PP. Nurul AbrorDokument1 SeiteDENAH - DUDUK - SEAT - 2 - 3 - 59 - PP. Nurul AbrorRoy Dari Pulau GaramNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPJS UmumDokument473 SeitenBPJS UmumklinikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Penyeliaan Penulisan Projek Ilmiah Syariah 2011Dokument24 SeitenPenyeliaan Penulisan Projek Ilmiah Syariah 2011Nadiah Nabihah SamsuddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- KJV Kej 4 Ayat 1-16Dokument3 SeitenKJV Kej 4 Ayat 1-16Rattan KnightNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Affiliated To The University of Rajasthan, Jaipur) : Roll No. of The Candidates Admitted in Session 2018-19Dokument6 Seiten(Affiliated To The University of Rajasthan, Jaipur) : Roll No. of The Candidates Admitted in Session 2018-19santosh somaniNoch keine Bewertungen

![The Siege Of Lucknow: A Diary [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259892857/149x198/ea3a79c26d/1617227774?v=1)

![History Of The Indian Mutiny Of 1857-8 – Vol. III [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259894313/149x198/9401c3f7cc/1617227774?v=1)

![The Relief of Chitral [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/319916121/149x198/60ba681405/1617218287?v=1)