Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rosenberg, Disease in History

Hochgeladen von

hector3nu3ezCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rosenberg, Disease in History

Hochgeladen von

hector3nu3ezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Disease in History: Frames and Framers

Author(s): Charles E. Rosenberg

Source: The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 67, Supplement 1. Framing Disease: The Creation and

Negotiation of Explanatory Schemes (1989), pp. 1-15

Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of Milbank Memorial Fund

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3350182

Accessed: 09/09/2010 15:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mmf.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Milbank Memorial Fund and Blackwell Publishing are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Milbank Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

Disease in History: Framesand Framers

CHARLES E. ROSENBERG

Universityof Pennsylvania

,M

i

EDICINE,

AN

OFTEN-QUOTED

HIPPOCRATIC

teaching explains, "consists in three things-the disease,

the patient, and the physician." When I teach an introductory course in the history of medicine, I always begin with disease.

There has never been a time that humankind has not suffered from

sickness, and the physician's specialized social role has developed in

response to it. Even when they assume the guise of priests or shamans,

doctors are by definition individuals presumed to have special knowledge or skills that allow them to treat men and women experiencing

pain or unable to work and fulfill family obligations.

But "disease" is an elusive entity. It is particularly difficult to

explain to college students who generally see it in simple pathophysiologic terms; the relation between somatic mechanism and social

consequence seems clear and unambiguous to even the most thoughtful

undergraduates. When pressed for a definition, their responses tend

to be one-dimensional: "something amiss in the body," one typical

example of the genre explains, "that causes pain or disability."

The reality is obviously a good deal more complex. Disease is at

once a biological event, a generation-specific repertoire of verbal constructs reflecting medicine's intellectual and institutional history, an

aspect of and potential legitimation for public policy, a potentially

defining element of social role, a sanction for cultural norms, and a

structuring element in doctor/patient interactions. In some ways disThe MilbankQuarterly,Vol. 67, Suppl. 1, 1989

? 1989 MilbankMemorialFund

I

CharlesE. Rosenberg

ease does not exist until we have agreed that it does-by perceiving,

naming, and responding to it (Rosenberg 1986).

Disease can, of course, be construed in one of its primary aspects

as the working out of a pathological process. As such it exists in

animals-who presumably do not socially construct their ailments and

negotiate attitudinal responses to sufferers-but who do experience

pain and impairment of function. And one can cite instances of human

disease that existed in a purely biological sense-certain inborn errors

of metabolism, for example-before their existence was disclosed by

an increasingly knowledgeable biomedical community. Nevertheless,

it is fair to say that in our culture a disease does not exist as a social

phenomenon until we agree that it does. And those acts of agreement

have during the past century become increasingly central to social as

well as medical thought (assuming the two can in some useful ways

be distinguished). Many physicians and laypersons have chosen, for

example, to label certain behaviors as disease even when a somatic

basis remains unclear-and possibly non-existent: one can cite the

instances of alcoholism, homosexuality, or "hyperactivity." As we are

well aware, the status of homosexuality as "disease"has been in recent

years an object of explicit and instructive contention (Bayer 1981).

Much has been written during the past two decades about the social

construction of illness. But in an important sense this is no more

than a tautology-a specialized restatement of the truism that men

and women construct themselves culturally. Every aspect of an individual's social identity is constructed-and thus also is disease.

Although this social-constructionist position has lost much of its

novelty during the past decade, it still serves to remind us of some

important things. Perhaps most significant is the fact that medical

thought and practice is rarely free of social and cultural constraint,

even in matters seemingly technical. The explanation of sickness is

too sensitive-socially and emotionally-for it to be a value-free enterprise. It is no accident that several generations of anthropologists

have assiduously concerned themselves with disease concepts in a

variety of non-Western cultures; agreed-upon etiologies at once incorporate and sanction a society's fundamental ways of organizing its

world. Medicine in the contemporary West is by no means divorced

from such affinities.

Some of those constraints reflect values, attitudes, and status relationships in the larger culture (of which physicians, like their pa-

Diseasein History

tients are part). But medicine, like the scientific disciplines to which

it has been so closely linked in the past century, is itself a social

system; even those technical aspects of medicine seemingly little subject to the importunate demands of cultural assumption are shaped

in part by the shared intellectual worlds and institutional structures

of particular communities of scientists and physicians. These realities

all interact to play a role in the process through which we formulate

and agree upon definitions of disease. In this sense, the term "social

history of medicine" is as tautological as that of the "social construction" of disease; every aspect of medicine's history is necessarily "social"-that acted out in laboratoryor library as well as at the bedside.

In the following pages I have, in fact, avoided the term social

construction. I felt it has tended to overemphasize functionalist ends

and the degree of arbitrarinessinherent in the negotiations that result

in accepted disease pictures. It has focused, in addition, on a handful

of socially resonant diagnoses-hysteria, chlorosis, neurasthenia, and

homosexuality, for example. It invokes, moreover, a particular style

of cultural criticism and particular moment in time. I have chosen

instead to use the less programmatically charged metaphor "frame"

rather than "construct" to describe the fashioning of explanatory

schemes for particular diseases.

During the past two decades, social scientists, historians, and physicians have shown a growing interest in disease and its history; the

attention paid social-constructivist views of disease is one aspect of a

multifaceted scholarly concern. The response to AIDS in recent years

has only added impetus to and focused public attention on an already

thriving academic enterprise.

The recent interest in the history of disease has reflected and incorporated a number of separate-and not always consistent-trends.

One is the emphasis among professional historians on social history

and the experience of ordinary men and women. Pregnancy and childbirth, for example, like epidemic disease have become an accepted

part of the standard historical canon. A second focus of interest in

disease centers on public health policy and a linked concern with

explanation of the demographic transition; how much credit should

go to specific medical interventions for the decline in morbidity and

lengthening life spans, and how much to changed economic and social

circumstances? The name of Thomas McKeown has been closely associated with revitalizing this century-old debate (McKeown and Re-

CharlesE. Rosenberg

cord 1962; McKeown 1976a, 1976b). Third, is the rebirth of what

might be called a new materialism in the form of an ecological vision

of history in which disease plays a key role-as, for example, in the

Spanish Conquest of Central and South America (Crosby 1972, 1986;

McNeill 1976). Fourth, has been the influence of demography among

a quantitatively oriented generation of historians and of history among

a growing number of demographers. The study of individual disease

provides one strategy for ascertaining the mechanisms underlying

aggregate change in morbidity and mortality figures. Finally, and

perhaps most widely influential, has been the growth of interest in

the way disease definitions and hypothetical etiologies can serve as a

tool of social control. Logically enough, such views have often been

associated with an emphasis on the social construction of disease (see,

among numerous examples, Wright and Treacher 1982; Figlio 1978).

Such interpretations are one aspect of a more general interest in the

relations among knowledge, the professions, and social power. Within

such formulations, physicians are construed as articulators and agents

of a broader hegemonic enterprise-the "medicalization" of society

one aspect of an oppressive ideological system.

What is often lost sight of in each of these emphases-and in the

aggregate in all-is the process of disease definition itself, and, second,

the consequences of those definitions once agreed upon in the lives

of individuals, in the making and discussion of social policy, and in

the structuring of medical care. We have, in general, failed to focus

on that nexus between biological event, its perception by patient and

practitioner, and the collective effort to make cognitive and policy

sense out of those perceptions. Yet, this process of recognition and

rationalization is a significant problem in itself, one that transcends

any single generation's time-bound effort to shape satisfactory conceptual frames for those biological phenomenon it regardsas of special

concern. Nor can it while men and women seek cure and understanding of their ills and physicians seek the reputation that comes with

innovation and publication. Where an underlying pathophysiologic

basis for a putative disease remains problematic-as in alcoholism for

example-we have another sort of framemaking, but one that nevertheless reflects in its style the plausibility and prestige of an unambiguously somatic, mechanism-oriented model of disease. This reductionist tendency has been logically and historically tied to another

characteristicof our thinking about disease-and that is its specificity.

Diseasein History

In our culture, its existence as specificentity is a fundamental aspect

of the intellectual and moral legitimacy of disease. If it is not specific,

it is not a disease and a sufferer not entitled to the sympathy-and

in recent decades often the reimbursement-connected with an agreedupon diagnosis.

Framing Disease

Disease begins with perceived and often physically manifest symptoms.

In all those centuries before the nineteenth, physicians and their

patients had to try to make sense out of these symptoms-imposing

an array of speculative mechanisms on the otherwise opaque body.

The condition called "dropsy" provides an excellent case in point.

As Steven Peitzman (1989) emphasizes in recounting SamuelJohnson's

experience of sickness, this was a familiar and ominous conditionone understood in parallel ways by patient and practitioner. The felt

and visible edema or "dropsy" implied fundamental internal dysfunction-but the precise nature of that dysfunction could hardly be

determined in the eighteenth century. Nor could edema arising from

a variety of sources be disaggregated by contemporary clinical skills.

Some dropsies seemed to respond to one diuretic or another, for

example, some temporarily, some with more lasting results (as in the

case of digitalis). "Dropsy" meant something very concrete to late

eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century practitioners and their patients alike. It is hardly surprising that physicians and educated laypersons should have employed the conceptual tools of a traditional

pathology with which to frame this familiar yet frightening clinical

phenomenon. Dropsy seemed to fit neatly into neohumoral models of

pathology with their emphasis on balance and intake and outgo; the

clinical reality of dropsy, with its accumulation of fluids and responsiveness to diuretics, seemed, in fact, to justify this speculative model,

just as the model helped frame the clinical reality.

But in the course of two centuries since Samuel Johnson's grim

illness, that phenomenon called dropsy came to be understood in

fundamentally different ways. For example, Richard Bright distinguished that portion of this symptom attributable to kidney dysfunction in the 1820s; he was able to associate a clinical picture

during life with post-mortem appearancesand with chemical changes

in the urine. Later in the nineteenth and into the twentieth century,

CharlesE. Rosenberg

clinicians defined and redefined that agreed-upon picture of Bright's

disease. Microscopic pathology focused on the fine structure of the

lesions characteristicallyassociated with renal disease. In the twentieth

century, the interests of a physiologically oriented and self-consciously

scientific generation of nephrologists turned to functional criteriasupplanting the anatomical, lesion-oriented conception of the disease

so influential in previous decades. Finally, Peitzman argues, we have

in the past two decades created a very different de facto framework

around renal dialysis; most patients never become dropsical at all and

their experience is that of dialysis and not the illness dialysis is meant

to avert. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) has a fundamentally administrative meaning today; it is an automatic trigger for reimbursing

providers of dialysis. Yet, ESRD is not simply an arbitraryneologism

spawned by bureaucratic necessity-but at one remove the reflection

of a real pathology interacting with a specific technology in specific

social and political circumstances. The evolving framework of pathological assumption explaining and describing "Bright's disease" has

been gradually integrated and reintegrated into a series of differently

focused explanatory frameworks for the same clinical pictures (for the

ability of medicine to alter the course of chronic renal disease remained,

as Peitzman emphasizes, minor until the dialysis era). It is precisely

this process of definition and redefinition that demands scholarly attention; it tells us a great deal about the evolution of medical thought

and practice. In another dimension it provides access into the experience of ordinary people during the past century.

If the materials available for framing disease can change, so can

those biological phenomena which demand framing. Peter English

(1989) reminds us of this complex and elusive aspect of disease history.

Rheumatic fever might well, he argues, not have existed in its nineteenth-century clinical form much before its perceived emergence

during that century of enormous social change. Yet as he also reminds

us, institutions and ideas in medicine were evolving at the same time.

The greater likelihood of hospitalization, for example, and the prominence of hospital-based studies in discerning and defining clinical

entities almost certainly played a role in framing what physicians came

to call rheumatic fever, with its characteristic-and attention-focusing-incidence of cardiac involvement. English is equally well aware

that the conceptual and technical tools to correlate systematically

appearances after death with symptoms in life did not really exist

Diseasein History

before the beginning of the nineteenth century. This timing constitutes an intricate and intractable, yet highly significant, dilemma.

How does one make sense of this interactive negotiation over time,

this framing of pathophysiologic reality in which the tools of the

framerand the picture to be framed may well have bothbeen changing

(and in which the relation between all instances of symptom-producing

interactions between humans and streptococci and that portion actually

identified as rheumatic fever remained unclear)?

The history of that clinical entity called rheumatic fever illustrates

not only a conceptual evolution, but a necessarily related and parallel

evolution in representation. The first clinical descriptions were presented in the discursive narrative form of individual doctor-patient

interactions (which came to include a revelatory coda in the form of

post-mortem results) so characteristic of the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth century. By mid-century, the disease was being represented

in the form of numerical aggregates summarizing hospital experience.

Walter B. Cheadles' depiction of rheumatic fever as a linked cluster

of symptom configurations constituted still another step in the evolution of efforts to represent-and in representing to legitimate-this

elusive clinical experience. In retrospect it is hardly surprising that

Cheadle's work should have appealed to contemporary practitioners.

It provided a viable-if schematic-compromise between a unified

yet abstract clinical entity and its protean manifestations in hospital

ward and consulting room. In more recent generations, of course,

laboratory findings became central to a new style of conceptualizing

and representing this elusive ailment.

As these studies of renal disease and rheumatic fever emphasize,

physicians have always been dependent on time-bound intellectual

tools and institutional arrangements in seeking to find and represent

patterns in the bewildering diversity of clinical phenomena. For a

physician in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as we

have suggested, neohumoral models were particularly important-and

used to rationalize such therapeutic measures as bleeding, purging,

and the lavish use of diuretics. With the emergence of pathological

anatomy in the early nineteenth century, hypothetical frameworks for

disease were increasingly fashioned in terms of specific lesions or

characteristic functional changes that would, if not modified, produce

lesions over time. The germ theory created another kind of framework

that could be used to impose a more firmly based taxonomic order

CharlesE. Rosenberg

on elusive configurations of clinical symptoms and post-mortem appearances. It seemed that it would be only a matter of time before

physicians understood all those mysterious ills that had puzzled their

professional predecessors for millennia; the relevant pathogenic microorganisms need only be found and their physiological or biochemical effects understood. This was an era, as is well known, in which

energetic-and sometimes overly credulous or ambitious-physicians

"discovered" microorganisms responsible for almost every ill known

to humankind.

In his discussion of parasitology, John Farley (1989) illustrates the

more general truth that particular framing options were not equally

available to would-be framers. The parasite model seemed in the first

half of the nineteenth century little relevant to most human ills. The

study of parasites was segregated intellectually-and thus in the formative decades of the germ theory the possibility of creating a unified

etiological theory was ignored. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, parasitology was institutionally segregated in schools

of tropical medicine, public health, and agriculture (paralleling the

marginalization of tropical medicine from the central foci of midtwentieth-century medicine in Europe, England, and North America).

Intellectual and institutional history defined, that is, certain options

as immediately accessible, defining others as relatively unavailable to

physicians and biologists as they sought understanding of particular

ills. The slowness to generalize models of parasitism to human disease

was as much a contingent aspect of a particular history as was the

often unthinking and mechanical application of other models-most

conspicuously in the parallel history of the bacteriological theory of

infectious disease.

But the framing of disease is in another of its dimensions rooted

in the necessities of care and the specific biological character of particular ailments. Tuberculosis provides a useful example. The most

important single cause of death (and an important factor impoverishing

families) in the nineteenth century, consumption provided a challenge

to policy makers and welfare authorities as well as to physicians.

Ubiquitous and discouraging, it constituted a problem of a very

different kind than, let us say, cholera, yellow fever, or typhoid. The

course of the disease was unpredictable and the great majority of

victims deteriorated gradually, hoping all the while to live and work

a normal life as long as they could; when that became impossible

Diseasein History

they needed food, warmth, and care. Many hospitals would not admit

them as incurable; most families could ill afford to care for wives,

husbands, and children when their symptoms became well defined

(Bates 1988). Romantic glorification of the consumptive was a rarefied

and largely literary phenomenon.

With Koch's demonstration of the tubercule bacillus (1882) and

the growing faith in sanitarium treatment, perceived options changed.

Yet, the situation was still a difficult one. Proving the contagiosity

of consumption posed a question; it did not provide answers. These

had to come from public authorities and private charity. Only gradually did these sources provide institutional care for the poor as well

as the prosperous-and only gradually did the medical and nursing

professions find an appropriate framework within which to organize

their own response. Even the apparent need to identify and isolate

sources of contagion did not lead to immediate sequestration of active

cases. Some physicians opposed such compulsory measures and then

refused to cooperate with notification requirements when imposed (Fox

1975). State and local governments were slow to provide the enormous

sums such a policy implied. Most physicians did not care to treat

patients who showed little tendency to recover-and those with more

attractive options avoided the isolated life of the tuberculosis sanitarium. Patients, on the other hand, were ordinarily loath to enter

treatment. Only their own needs (and that of their often exhausted

families) coupled with the desire to pursue the institution's promise

of remission made individuals willing to undertake sanitarium

treatment.

The biological characterof particular ills helps define public health

policies as well as therapeutic options. Tuberculosis provides only one

sort of example. Acute ills obviously provide a very different challenge

to physicians, governments, and medical institutions. But even acute

infections vary in their modes of transmission, for example, and thus

in their specific social identity. Attitudes toward sexuality and the

need to change individual behavior, for example, constrain efforts to

halt the spread of syphilis (Brandt 1985). To cite another sort of

instance, water-borne ailments like typhoid or cholera could be interdicted by the skills of bacteriologist and civil engineer and the

decisions of local government-without the need to alter individual

habits.

I do not mean to imply that such decisions were no more than

Io

CharlesE. Rosenberg

enlightened responses to medicine's changing understanding of the

transmission of such ills. Particular decisions to build new water

systems reflected political alliances, economic pressures, and social

perceptions-including attitudes toward the medical profession and

toward infectious disease itself.

Disease as Frame

Once crystallized in the form of specific entities and seen as existing

in particular individuals, disease serves as a social actor and mediator.

This is an ancient truth. It would have hardly surprised a leper in

the twelfth century, or a plague victim in the fourteenth. Nor, in

another way, would it have surprised a "sexual invert" at the end of

the nineteenth century.

These instances remind us of a number of important facts. One is

the role played by laymen as well as physicians in shaping the total

experience of sickness. Another is that the act of diagnosis itself

becomes a key event in the experience of illness; logically related to

this point is the way in which each disease is invested with a unique

configuration of social characteristics-and thus triggers disease-specific attitudinal responses. Once articulated and accepted, disease entities became "actors"in a complex social situation. Finally, of course,

our case studies suggest that this process is deeply embedded in human

history. The nineteenth century may have changed the style and

content of individual diagnoses-and expanded the conventional

boundaries of illness especially in the sphere of behavior-but it did

not initiate the social centrality of disease concepts and the social

significance of diagnoses once made.

Michael MacDonald's (1989) study of suicide in early modern England underlines both the antiquity and negotiated quality of disease

definitions; it illustrates as well the possibility of medicalizing behavior

and thus changing its moral-and in the case of suicide, legalmeaning. Perhaps most strikingly, it illustrates the way in which

medical personnel and formal medical thinking constituted only one

factor in a diverse social and intellectual context. Suicide became

increasingly a retrospective evidence of exculpatory disease-as in

instance after instance ordinary Englishmen preferred that option to

its legally and traditionally mandated alternative. They chose not to

label their deceased family members, friends, and neighbors as crim-

Disease in History

II

inally responsible for their final act-and in doing so to forfeit their

property to the state. It provides as well an instance in which behavior

alone could serve as the crucial element in a "diagnosis" of "sickness."

Certainly the circumstances surrounding suicide-the need to negotiate concrete determinations at a particular moment in time, for

example, and the gradient defined by the harsh and brutal alternatives

to a verdict of unsound mind-are a bit atypical. And so is the

chronology; a willingness to expand the boundariesof legitimate illness

so as to include behavior is more typically characteristic of the nineteenth century.

The expansion of diagnostic categories in the late nineteenth century

did create a new set of putative clinical entities that seemed controversial at first, and certainly served as one variable in defining the

feelings of particular individuals about themselves, and of society about

those individuals. Inevitably, the controversy turned on matters of

value and responsibility as well as epistemological status. Was the

alcoholic a victim of sickness or of willful immorality? And if sickness,

what was its somatic basis? Was the individual sexually attracted by

members of the same sex simply a depraved person who chose to

commit unspeakable acts, or a personality type whose behavior was

in all likelihood the consequence of hereditary endowment (Weeks

1981; Hansen 1989; D'Emilio and Freedman 1988)?

It is clear that such dilemmas are not simply an incident in the

intellectual history of medicine, but an important symptom of changing social values more generally-and as well, of course, a factor in

the lives of particular men and women. It is equally clear that this

style of social negotiation is very much alive today as physicians and

society debate issues of risk and life-style, and as government and

experts assess deviance and evaluate modes of social intervention. The

historian can hardly decide whether the creation of such diagnoses

was positive or negative, constraining or liberating, for particular

individuals, but the creation of homosexuality as a medical diagnosis,

for example, certainly altered the variety of options available to individuals forframing themselves,their behavior, its nature and meaning.

It offered the possibility-for better or worse-of construing the same

behaviors in a new way and of shaping a novel role for the physician

in relation to that behavior (sometimes in courts or in the administrative routine of education and social welfare).

But this is not only true of such morally and ideologically charged

12

CharlesE. Rosenberg

diagnoses. Even diseases such as cancer and tuberculosis, as we have

seen, shaped individual lives in the nineteenth century-just as a

late-twentieth-century diagnosis of heart disease becomes an aspect of

individual personality, to be integrated in ways appropriate to personality and social circumstance. Diet and exercise, anxiety, avoidance

or depression can all constitute aspects of that integration. Once

diagnosed as epileptic, to cite another example, in centuries before

our own-or as a sufferer from cancer or schizophrenia in our generation-an individual becomes in part that diagnosis.

The technical elucidation of somatic disease pictures could add toor refine-the existing vocabulary of disease entities. The nineteenth

century saw a host of such developments. The discovery of leukemia

as a distinctive clinical entity, for example, created a new and suddenly

altered identity for those individuals the microscope disclosed as incipient victims. Before that diagnostic possibility they might have

felt debilitating symptoms-but symptoms to which they could not

put a name. With that diagnosis, the patient becomes an actor in a

suddenly altered narrative. Every new diagnostic tool has the potential

for creating similar consequences-even in individuals who had felt

no symptoms of illness. Mammography, for example, can suggest the

presence of carcinoma in women entirely symptom free. Once that

radiological suggestion is confirmed, an individual's life is irrevocably

changed.

For centuries disease-both specific and generic-has played another

role as well. It has helped frame debates about society and social

policy; since at least Biblical times the incidence of disease has served

as index and monitory comment on society. Since at least the eighteenth century, physicians and social commentators have used the

difference between "normal" and extraordinary levels of sickness as

an implicit indictment of pathogenic environmental circumstances.

Military surgeons worried, for example, about the alarming incidence

of camp and hospital disease; the frequency of death and disabling

sickness in a youthful male population underlined the need for reform

in existing camp and barrackarrangements. Medical men in Europe's

new industrial cities pointed to the incidence of fevers and infant

deaths among tenement dwellers as evidence of the need for environmental reform; the instructive and unquestioned disparity between

morbidity and mortality statistics in rural as opposed to urban populations constituted, for example, a compelling case for public health

Disease in History

reform (cf., for example, Eyler 1979; Coleman 1982). A perceived

gap between the is and the oughtto be has often constituted a powerful

rationale for social action.

The rich historical tradition of social medicine as implicit social

criticism was built around the analysis of disease incidence. Henry

Sigerist in the 1930s, for example, like many of his generation, saw

disease incidence as in part a consequence of-and comment oncapitalist social relations; in his younger years, as Elizabeth Fee (1989)

emphasizes, Sigerist had tended to view disease as a reflection of

culture. What both of Sigerist's positions had in common was a

centuries-old emphasis on the relation between particular incidences

of disease and particular social realities.

But as John Eyler (1989) demonstrates in his discussion of Arthur

Newsholme's thought, this style of social analysis was complex and

often self-contradictory. Were individuals responsible for the behavior

that placed them at risk-or were they passive victims of inimical

social circumstances? Few physicians could ignore either kind of causation-and, in fact, were well aware that both factors could interact,

creating "vicious cycles" of poverty, environmental deprivation, immorality, and ultimate and inevitable disease. In this sense disease

became an occasion and agenda for a generation-long debate about

the relation among state policy, medical responsibility, and individual

culpability. It is a debate that has hardly ceased-as the recent outbreak of AIDS has so forcefully emphasized.

AIDS is more than a metaphor for something else-though like

plague or cholera it is necessarily that as well. It has reminded us

that infectious disease is not simply an occasion for researchand clinical

investigation or the blaming of victims, but potentially a matter of

life and death. It is a forceful reminder that we have not banished

infectious disease-as we have famine-from the developed world.

Earlier generations were hardly in need of such enlightenment. Epidemic disease has been omnipresent in human history and thus fundamental in the negotiation of social values, attitudes, and individual

identities. A growing academic concern in recent decades is no more

than a respectful obeisance to a fundamental aspect of perceived social

reality in every culture, in every time and every place.

Although we have begun to study the history of disease and have

cultivated a growing appreciation of the potential significance of such

studies, much remains to be done. As the following pages suggest,

I4

CharlesE. Rosenberg

the study of disease constitutes a multidimensional sampling device

for the scholar concerned with the relation between social thought

and social structure. Although it has been a traditional concern of

physicians, antiquarians, and moralists, the study of disease in modern

society is still a comparatively novel one for social scientists. It is

more an agenda for future research than a repository of rich scholarly

accomplishment. We need to know more about the individual experience of disease in time and place, the influence of culture on

definitions of disease and of disease in the creation of culture, and

the role of the state in defining and responding to disease. We need

to understand the organization of the medical profession and institutional medical care as in part a response to particular patterns of

disease incidence. The list could easily be extended, but its implicit

burden is clear enough. Disease constitutes a fundamental substantive

problem and analytical tool-not only in the history of medicine, but

in the social sciences generally.

References

Bates, B. 1988. Quid Pro Quo in Chronic Illness: The Case of Consumption, 1876-1900. Paper delivered at the Conference on the

History of Disease, College of Physicians of Philadelphia, March

11-12.

Bayer, R. 1981. Homosexualityand AmericanPsychiatry:The Politics of

Diagnosis. New York: Basic Books. (Revised ed., 1987. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.)

Brandt, A.M. 1985. No Magic Bullet. A Social History of Venereal

Disease in the United States since 1880. New York: Oxford University Press.

Coleman, W. 1982. Disease Is a Social Disease: Public Health and

Political Economyin Early Industrial France. Madison: University

of Wisconsin Press.

Crosby, Jr. A.W. 1972. The ColumbianExchange.Biologicaland Cultural Consequences

of 1492. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood.

. 1986. EcologicalImperialism.TheBiologicalExpansionof Europe,

900-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D'Emilio, J., and E.B. Freedman. 1988. IntimateMatters. A History

of Sexuality in America. New York: Harper and Row.

English, P.C. 1989. Emergence of Rheumatic Fever in the Nineteenth

Century. Milbank Quarterly67 (Suppl. 1):33-49.

Diseasein History

I5

Eyler, J.M. 1979. VictorianSocial Medicine. The Ideas and Methodsof

William Farr. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

. 1989. Poverty, Disease, Responsibility: Arthur Newsholme

and the Public Health Dilemma of British Liberalism. Milbank

Quarterly67 (Suppl. 1):109-126.

Farley, J. 1989. Parasites and the Germ Theory of Disease. Milbank

Quarterly67 (Suppl. 1):50-680.

Fee, E. 1989. Henry E. Sigerist: From the Social Production of Disease

to Medical Management and Scientific Socialism. Milbank Quarterly 67 (Suppl. 1):127-150.

Figlio, K. 1878. Chlorosis and Chronic Disease in 19th Century

Britain: The Social Constitution of Somatic Illness in a Capitalist

Society. Social History 3:167-97.

Fox, D.M. 1975. Social Policy and City Politics: Tuberculosis Reporting in New York, 1889-1900. Bulletin of the Historyof Medicine 49:169-95.

Hansen, B. 1989. American Physicians' Earliest Writings about Homosexuality, 1880-1900. Milbank Quarterly67 (Suppl. 1):92108.

MacDonald, M. 1989. The Medicalization of Suicide in England:

Laymen, Physicians, and Cultural Change, 1500-1870. Milbank

Quarterly67 (Suppl. 1):69-91.

McKeown, T. 1976a. The ModernRise of Population.London: Edward

Arnold.

1976b. The Role of Medicine,Dream, Mirage or Nemesis.London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust.

McKeown, T., and R.G. Record. 1962. Reasons for the Decline in

Mortality in England and Wales during the Nineteenth Century.

PopulationStudies 16:94-122.

McNeill, William H. 1976. Plaguesand Peoples.Garden City, N.Y.:

Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Peitzman, S.J. 1989. From Dropsy to Bright's Disease to End-stage

Renal Disease. Milbank Quarterly67 (Suppl. 1):16-32.

Rosenberg, C.E. 1986. Disease and Social Order in America: Perceptions and Expectations. Milbank Quarterly64 (Suppl. 1):3455.

Weeks, J. 1981. Sex, Politics and Society. The Regulationof Sexuality

Since 1800. London: Longman.

Wright, P., and A. Treacher. 1982. The Problemof MedicalKnowledge.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

to:CharlesE. Rosenberg,Ph.D., Departmentof History

Address

correspondence

and Sociologyof Science, School of Arts and Sciences,Universityof Pennsylvania,215 South 34th Street, Philadelphia,PA 19104-6310.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Krieger Nancy Epidemiology and The PeopleDokument394 SeitenKrieger Nancy Epidemiology and The PeopleAnamaria Zaccolo100% (1)

- Purnanandalahari p3D4Dokument60 SeitenPurnanandalahari p3D4anilkumar100% (1)

- ScreenwritingDokument432 SeitenScreenwritingkunalt09100% (4)

- Anthropology of Psychiatry. Tsao - 2009Dokument11 SeitenAnthropology of Psychiatry. Tsao - 2009Pere Montaña AltésNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Virus Misconception, Part III (Mobile Version)Dokument22 SeitenThe Virus Misconception, Part III (Mobile Version)Franco CognitiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aligning With New Digital Strategy A Dynamic CapabilitiesDokument16 SeitenAligning With New Digital Strategy A Dynamic Capabilitiesyasit10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Critical reflections on AIDS and social sciencesDokument7 SeitenCritical reflections on AIDS and social scienceselihusserlNoch keine Bewertungen

- NancyWaxler LeperDokument11 SeitenNancyWaxler Leperinamul.haque23mphNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buku Medicale PDFDokument348 SeitenBuku Medicale PDFRoso SugiyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Language Shapes Color MemoryDokument18 SeitenHow Language Shapes Color Memoryhector3nu3ezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pandemic Syllabus: by David Barnes, Merlin Chowkwanyun, & Kavita SivaramakrishnanDokument5 SeitenPandemic Syllabus: by David Barnes, Merlin Chowkwanyun, & Kavita Sivaramakrishnanramón adrián ponce testinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medicine As An Institution of Social Control : Irving Kenneth ZolaDokument19 SeitenMedicine As An Institution of Social Control : Irving Kenneth ZolaleparrasNoch keine Bewertungen

- MATH 8 QUARTER 3 WEEK 1 & 2 MODULEDokument10 SeitenMATH 8 QUARTER 3 WEEK 1 & 2 MODULECandy CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hahn, R. 1995. Sickness and Healing - An Anthropological Perspective. Chap 4 - The Role of Society and Culture in Sickness and HealingDokument24 SeitenHahn, R. 1995. Sickness and Healing - An Anthropological Perspective. Chap 4 - The Role of Society and Culture in Sickness and HealingJenny Gill67% (3)

- Culture, Health and Illness: An Introduction for Health ProfessionalsVon EverandCulture, Health and Illness: An Introduction for Health ProfessionalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bury, M. (1986) Social Constructionism and The Development of Medical Sociology, Sociology of Health and IllnessDokument34 SeitenBury, M. (1986) Social Constructionism and The Development of Medical Sociology, Sociology of Health and Illness張邦彥Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2008 Epi Critica IJEDokument6 Seiten2008 Epi Critica IJESamuel Andrés AriasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Construction of Illness: Key Insights and Policy ImplicationsDokument14 SeitenSocial Construction of Illness: Key Insights and Policy ImplicationsmymagicookieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diego Armus, The Ailing CityDokument3 SeitenDiego Armus, The Ailing CityOrlando Deavila PertuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Sociology of Pandemics Is ImportantDokument7 SeitenWhy Sociology of Pandemics Is ImportantMahin S RatulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Illness Narratives: Fact or Fiction? Mike BuryDokument23 SeitenIllness Narratives: Fact or Fiction? Mike BuryruyhenriquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Causation and Social ConstructionDokument6 SeitenSocial Causation and Social Constructionhuberpadilla100% (1)

- 1 Link and Phelan 1995 Fundamental Cause TheoryDokument16 Seiten1 Link and Phelan 1995 Fundamental Cause TheoryAsif IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Suffering and EmbodimentDokument11 SeitenSocial Suffering and EmbodimentantonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conrad y Barker (2010) The Social Construction of Illness - Key Insights and Policy ImplicationsDokument13 SeitenConrad y Barker (2010) The Social Construction of Illness - Key Insights and Policy ImplicationsEduardo Gon-FaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risky Bodies, Drugs and Biopolitics - On The Pharmaceutical Governance of Addiction and Other Diseases of Risk.'Dokument23 SeitenRisky Bodies, Drugs and Biopolitics - On The Pharmaceutical Governance of Addiction and Other Diseases of Risk.'Charlotte AgliataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing A Critical Perspective in MedicalDokument2 SeitenDeveloping A Critical Perspective in MedicalNico K Ni PecsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008 Breilh 745 50Dokument6 SeitenInt. J. Epidemiol. 2008 Breilh 745 50Luis LeaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- POPAY, Jennie. Public Health Research and Lay Knowledge.Dokument10 SeitenPOPAY, Jennie. Public Health Research and Lay Knowledge.Vinícius MauricioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breilh, J-CON-007-Latin AmericanDokument7 SeitenBreilh, J-CON-007-Latin AmericanPaula FrancineideNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conrad & Barker - The Social Construction of IllnessDokument14 SeitenConrad & Barker - The Social Construction of Illnesstomaa08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Borderline Personality DisorderDokument9 SeitenBorderline Personality DisorderLCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Illness and The Politics of Social Suffering: Towards A Critical Research Agenda in Health and Science StudiesDokument25 SeitenIllness and The Politics of Social Suffering: Towards A Critical Research Agenda in Health and Science StudiesNicolas VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- There Life After Foucault? Poststructuralism and The Health Social SciencesDokument3 SeitenThere Life After Foucault? Poststructuralism and The Health Social SciencesPedro Fontes MontanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Determinants of HealthDokument24 SeitenThe Determinants of HealthcschnellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hisc 108Dokument4 SeitenHisc 108Paula GilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Berkman&Kawachi Historical FrameworkDokument10 SeitenBerkman&Kawachi Historical Frameworkalvaroeduardolemos7959Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sociology MTO 1Dokument15 SeitenSociology MTO 1bnvjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bibeau, G. (1997) - at Work in The Fields of Public Health The Abuse of Rationality.Dokument8 SeitenBibeau, G. (1997) - at Work in The Fields of Public Health The Abuse of Rationality.Santiago GalvisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kleinman 1986Dokument12 SeitenKleinman 1986Valentina QuinteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lezione 2 Soc Suf IngleseDokument5 SeitenLezione 2 Soc Suf IngleseantonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conservative Thought in Applied AnthropologyDokument4 SeitenConservative Thought in Applied AnthropologyBORISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nature and NurtureDokument14 SeitenNature and NurtureCL PolancosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ensaio Sobre Antropologia Da SaudeDokument45 SeitenEnsaio Sobre Antropologia Da SaudeAparicio NhacoleNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Changing Face of Medical Sociology: David WainwrightDokument18 SeitenThe Changing Face of Medical Sociology: David WainwrightHelly Chane LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nguyen and PeschardDokument29 SeitenNguyen and Peschardsiamese_catNoch keine Bewertungen

- Krieger Nancy Epidemiology and the People-1-297Dokument297 SeitenKrieger Nancy Epidemiology and the People-1-297Luiza MenezesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preguntas Historia de La Medicina 2013Dokument47 SeitenPreguntas Historia de La Medicina 2013Jaime MatarredonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnthropologyDokument17 SeitenAnthropologyankulin duwarahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociology and Health ArticleDokument19 SeitenSociology and Health ArticleAna Victoria Aguilera RangelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Queer Theory and Biomedical Practice The BiomedicaDokument15 SeitenQueer Theory and Biomedical Practice The BiomedicaAbdullah Al MashoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- 30.08.22 - All Medicine Is SocialDokument4 Seiten30.08.22 - All Medicine Is SocialPola PhotographyNoch keine Bewertungen

- tmpB4EC TMPDokument21 SeitentmpB4EC TMPFrontiersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timmermans and Haas - (2008) Towards A Sociology of DiseaseDokument18 SeitenTimmermans and Haas - (2008) Towards A Sociology of DiseaseVanesa IBNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Anthropology of Public HealthDokument5 SeitenThe Anthropology of Public Healthransanaalwis13Noch keine Bewertungen

- Legitimating Life: Adoption in the Age of Globalization and BiotechnologyVon EverandLegitimating Life: Adoption in the Age of Globalization and BiotechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary Sociology A Journal of ReviewsDokument3 SeitenContemporary Sociology A Journal of ReviewsRuoan XiaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical P On Health and MedicineDokument2 SeitenTheoretical P On Health and MedicineMuhsin Sa-eedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Anthropology NoteDokument37 SeitenMedical Anthropology NoteKeyeron DugumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Untitled DocumentDokument12 SeitenUntitled DocumentKritika GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding epidemic psychologyDokument12 SeitenUnderstanding epidemic psychologyJason DuncanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rosenberg ContestedDokument19 SeitenRosenberg ContestedAnonymous NdEHQyTZKNoch keine Bewertungen

- GabeJonathanMon 2013 Part3HealthKnowledgeA KeyConceptsInMedicalSDokument40 SeitenGabeJonathanMon 2013 Part3HealthKnowledgeA KeyConceptsInMedicalSElla YtxcqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dupré (2018) The Metaphysics of EvolutionDokument9 SeitenDupré (2018) The Metaphysics of Evolutionhector3nu3ezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homeostasis Higher Taxa and MonophylyDokument18 SeitenHomeostasis Higher Taxa and Monophylyhector3nu3ezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dretske, F. 1997 Naturalizing The Mind CambridgeDokument20 SeitenDretske, F. 1997 Naturalizing The Mind Cambridgehector3nu3ezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sellars Emp Phil MindDokument36 SeitenSellars Emp Phil MindsemsemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nominal RestrictionDokument26 SeitenNominal Restrictionhector3nu3ezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does Practical Rationality Constrain Epistemic RationalityDokument13 SeitenDoes Practical Rationality Constrain Epistemic Rationalityhector3nu3ezNoch keine Bewertungen

- GABA-Activated CL - Channels in Astrocytes of Hippocampal SlicesDokument7 SeitenGABA-Activated CL - Channels in Astrocytes of Hippocampal Sliceshector3nu3ezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calendario ATP 2016Dokument2 SeitenCalendario ATP 2016Yo Soy BetoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Realism o CientificoDokument128 SeitenRealism o CientificoManuel Vargas TapiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calendario ATP 2016Dokument2 SeitenCalendario ATP 2016Yo Soy BetoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nodelman 1992Dokument8 SeitenNodelman 1992Ana Luiza RochaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viscosity IA - CHEMDokument4 SeitenViscosity IA - CHEMMatthew Cole50% (2)

- Iso 696 1975Dokument8 SeitenIso 696 1975Ganciarov MihaelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analog Communication Interview Questions and AnswersDokument34 SeitenAnalog Communication Interview Questions and AnswerssarveshNoch keine Bewertungen

- IELTS Writing Task 2/ IELTS EssayDokument2 SeitenIELTS Writing Task 2/ IELTS EssayOlya HerasiyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Single-phase half-bridge inverter modes and componentsDokument18 SeitenSingle-phase half-bridge inverter modes and components03 Anton P JacksonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nec TutorialDokument5 SeitenNec TutorialbheemasenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PremiumpaymentReceipt 10663358Dokument1 SeitePremiumpaymentReceipt 10663358Kartheek ChandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Polifur 1K Synthetic Top Coat MSDS Rev 2 ENDokument14 SeitenPolifur 1K Synthetic Top Coat MSDS Rev 2 ENvictorzy06Noch keine Bewertungen

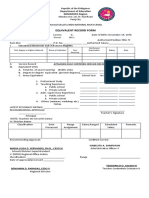

- Equivalent Record Form: Department of Education MIMAROPA RegionDokument1 SeiteEquivalent Record Form: Department of Education MIMAROPA RegionEnerita AllegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- VIACRYL VSC 6250w/65MP: Technical DatasheetDokument2 SeitenVIACRYL VSC 6250w/65MP: Technical DatasheetPratik MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DX DiagDokument42 SeitenDX DiagVinvin PatrimonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mechanics of Materials: Combined StressesDokument3 SeitenMechanics of Materials: Combined StressesUmut Enes SürücüNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test 1 Grammar, Revised Ecpe HonorsDokument3 SeitenTest 1 Grammar, Revised Ecpe HonorsAnna Chronopoulou100% (1)

- My RepublicDokument4 SeitenMy Republicazlan battaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JASA SREVIS LAPTOP Dan KOMPUTERDokument2 SeitenJASA SREVIS LAPTOP Dan KOMPUTERindimideaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TG KPWKPDokument8 SeitenTG KPWKPDanmar CamilotNoch keine Bewertungen

- User Manual: C43J890DK C43J892DK C49J890DK C49J892DKDokument58 SeitenUser Manual: C43J890DK C43J892DK C49J890DK C49J892DKGeorge FiruțăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atomic Structure - One Shot by Sakshi Mam #BounceBackDokument231 SeitenAtomic Structure - One Shot by Sakshi Mam #BounceBackchansiray7870Noch keine Bewertungen

- Optimize Supply Network DesignDokument39 SeitenOptimize Supply Network DesignThức NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparison of Fuel Cell Testing Protocols PDFDokument7 SeitenA Comparison of Fuel Cell Testing Protocols PDFDimitrios TsiplakidesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iwwusa Final Report IdsDokument216 SeitenIwwusa Final Report IdsRituNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assurance Audit of Prepaid ExpendituresDokument7 SeitenAssurance Audit of Prepaid ExpendituresRatna Dwi YulintinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hope 03 21 22Dokument3 SeitenHope 03 21 22Shaina AgravanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4439 Chap01Dokument28 Seiten4439 Chap01bouthaina otNoch keine Bewertungen

- RRC Igc1Dokument6 SeitenRRC Igc1kabirNoch keine Bewertungen