Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Topic 1 - Theories of The MNCs

Hochgeladen von

Alex UrdaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Topic 1 - Theories of The MNCs

Hochgeladen von

Alex UrdaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Theories of foreign direct investment

3.

4.

5.

83

a recognition by some economists, notably Williams (1929), that the internationalisation of some industries required a modication to neoclassical theories of trade;

an appreciation that the common ownership of the cross-border activities of rms

could not only be considered as a substitute for the international cartels and combines (Plummer, 1934), but could also be explained, in part at least, by the perceived

gains of vertical or horizontal integration (Penrose, 1956; Bye, 1958); and.

an extension of the extant theory of international capital movements to embrace the

role of entrepreneurship and business competence (Lund, 1944). Lund refers to this

combination of entrepreneurial ideas and nancial capital as an international

wandering combination.108

Byes contribution, which was (and still is) generally neglected by economists was particularly perceptive. It was he who coined the expression the multi-territorial rm and

used the case of the international oil industry to demonstrate that real and nancial size

enables rms to cross varying thresholds of growth either by extension or integration, and

so assure them of a certain bargaining position (Bye, 1958:161).

The 1960s saw two inuential and pathbreaking contributions to the theory of the

MNE and MNE activity. Each was put forward quite independently of the other, and

approached its subject matter from a very dierent perspective. The following subsections

briey describe the main features of the two approaches.

4.2.2

The Contribution of Hymer

The rst contribution was that of Hymer (1960, 1968) who, in his PhD thesis,109 expressed

his dissatisfaction with the theory of indirect (or portfolio) capital transfers to explain the

foreign value-added activities of rms. In particular, he identied three reasons for his discontent. The rst was that once risk and uncertainty, volatile exchange rates and the cost

of acquiring information and making transactions were incorporated into classical portfolio theory, many of its predictions, for example, with respect to the cross-border movements of money capital in response to interest rate changes, became invalidated. This was

because such market imperfections altered the behavioural parameters aecting the

conduct and performance of rms and, in particular, their strategy in servicing foreign

markets.

Second, Hymer asserted that FDI involved the transfer of a package of resources (technology, management skills, entrepreneurship and so on), and not just nance capital

which portfolio theorists such as Iversen (1935) had sought to explain. Firms were motivated to produce abroad by the expectation of earning an economic rent on the totality

of their resources, including the ways in which they were organised. The third and perhaps

most fundamental characteristic of FDI was that it involved no change in the ownership

of resources or rights transferred, whereas indirect investment, which was transacted

through the market, did necessitate such a change. In consequence, the organisational

modality of both the transaction of the resources (for example, intermediate products)

and the value-added activities linked by these transactions was dierent.

In this connection, it is perhaps worth observing that Hymer was only interested in FDI

in so far as this was the means by which rms were able to control the use of property

rights transferred to their foreign subsidiaries. In his thesis, Hymer broached many other

Theories of foreign direct investment

85

argument, Hymer did appear to acknowledge that MNEs might help to improve international resource allocation by circumventing market failure. To this extent at least, his

1968 contribution is a natural point of departure for the more rigorous work of the internalisation economists in the following decade.112

4.2.3

The Product Cycle

If Hymer used industrial and organisational economics to explain MNE activity, Vernon

and his colleagues at Harvard were the rst to acknowledge the relevance of some of the

newer trade theories put forward in the 1950s and 1960s113 to help explain this phenomenon. In a classic article published in 1966, Vernon used a microeconomic concept

the product cycle to help explain a macroeconomic phenomenon, namely, the foreign

activities of US MNEs in the post-war period. His starting-point was that, in addition to

immobile natural endowments and human resources, the propensity of countries to

engage in trade also depended on the capability of their rms to upgrade these assets or

to create new ones, notably technological capacity. He also hypothesised that the eciency

of rms in organising these human and physical assets was, in part at least, country

specic in origin.

Drawing upon some earlier work by Posner (1961), Vernon (1966) argued that the competitive or ownership advantages of US rms particularly their willingness and capabilities to innovate new products and processes was determined by the structure and

pattern of their home country factor endowments, institutions and markets. However,

it was quite possible that any initial competitive advantage enjoyed by innovating enterprises might be eroded or eliminated by the superior competence of rms in other

countries to supply the products based on them. Without explicitly bringing market

imperfections into his analysis, Vernon then switched his unit of analysis to the rm, and

particularly to the location of its production. Initially, the product (or more correctly, the

value-added activities based on the rms proprietary assets) was produced for the domestic consumption in the home country, near to its innovatory activities and/or markets. At

a later stage of the product cycle, because of a favourable combination of innovating and

production advantages oered by the US, it was exported to other countries most similar

to it in their demand patterns and supply capabilities.

Gradually, as the product becomes standardised or mature, the competitive advantages

of the supplying rms were seen to change from those to do with the uniqueness of

product per se, to their ability to minimise the costs of value-adding activities and/or their

marketing expertise. The pressure to ensure cost eciency mounts as imitators start

making inroads into the market. At the same time, as consumer demand becomes more

price elastic, as labour becomes a more important ingredient of costs and as foreign

markets expand, the attractions of siting value-added activities in a foreign rather than

domestic location increase. This might be hastened by the imposition of trade barriers or

in anticipation of competitors setting up in these markets. Eventually, Vernon argued, if

conditions in the host country were right, the aliate might replace exports from the

parent company or even export back to it.

This approach to explaining foreign production was essentially an extension of the neoclassical theory of the spatial distribution of factor endowments to embrace intermediate products. It also acknowledged that strategic factors, arising from an oligopolistic

Theories of foreign direct investment

87

cultural characteristics of their countries of origin were dierent (Franko, 1976).

Hypotheses intended to explain the structure of outward and inward FDI in the 1960s

and 1970s were frequently found to be unsatisfactory in explaining that of the 1980s and

1990s (UNCTAD, 1998, 2003b).

Stephen Magee (1977a, 1977b), in a more detailed examination of technology as a

valued intangible asset, took a rather dierent line. He was primarily interested in why the

incentive of rms to internalise the market for technology varied over time. He coined

the concept of the industry technology cycle, which built upon the Vernon hypothesis that

the competitive advantages of rms were likely to change over the life of the product. He

argued that rms were unlikely to sell their rights to new and idiosyncratic technology for

two reasons. First the fear that, as a result of information asymmetries, the buying rm

was unlikely to pay the selling rm a price that would yield at least as much economic rent

as it could earn by using the technology itself. Second, the concern that the licensee might

use the technology to the disadvantage of the licensor, and even become a competitor to

it. As the technology matured, however, and lost some of its uniqueness, the need to internalise its use evaporated and the rm would consider switching its modality of transfer

from FDI to licensing.

Around the same time, another group of scholars began to focus more specically on

the variables inuencing the decision of rms to license their property rights as an alternative to FDI (Telesio, 1979; Contractor, 1981). However, although these scholars began

to identify, more carefully, the circumstances in which rms might wish to control the use

of the technological assets that they possessed, they did not really grapple with the more

fundamental issue of the organisation of transactional relationships as part of a general

paradigm of market failure. This task was left to another group of economists (see

Section 4.3).

Other researchers mainly from a business school tradition, and often from Harvard

itself built on the Vernon approach. A monograph summarising some empirical

research on the product cycle appeared in 1972 (Wells, 1972). Work on UK, continental

European and Japanese MNEs closely paralleled that on US MNEs (Franko, 1976;

Stopford, 1976; Tsurumi, 1976; Yoshino, 1976). Perhaps of greater signicance for the

development of the theory of foreign production at this time were the ndings of a group

of Vernons students, notably Knickerbocker (1973), Graham (1975, 1978) and Flowers

(1976), that it was not just locational variables that determined the spatial distribution of

the economic activity of rms, but their strategic response to these variables, and to the

anticipated behaviour of their competitors.115 In a perfectly competitive market situation,

strategic behaviour (like the rm itself) is a black box. This is simply because the rm has

no freedom of action if it is to earn at least the opportunity cost of its investments. Its

maximum and minimum prot positions are one and the same thing. However, once

markets become imperfect as a result of structural distortions, uncertainty, externalities

or economies of scale, then strategy begins to play an active role in aecting business

conduct (Dunning, 1993a).

Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in an oligopolistic market situation. For more than

a century, economists have acknowledged that output and price equilibrium depends on

the assumptions made by one rm about how its own behaviour will aect that of its

competitors, and how, in turn, this latter behaviour will impinge upon its own protability. Knickerbocker (1973) argued that, as risk minimisers, oligopolists wishing to avoid

Theories of foreign direct investment

89

But, whereas Hymer viewed FDI primarily as an aggressive strategy by rms to advance

their monopoly power, Vernon and his colleagues perceived it more as a defensive strategy by rms to protect their existing market positions.

4.2.5

Other Theoretical Contributions: A Selected View

To complete this short historical review, we briey consider three other approaches to

explaining MNE activity which, when reinterpreted in terms of contemporary theorising,

oered (and still oer) valuable insights into both the location and ownership of international economic activity. Two of the approaches were developed by nancial or macro

economists, while the third one relies on a behavioural explanation of MNE activity.

The risk diversication hypothesis

The risk diversication hypothesis was rst put forward by Lessard (1976, 1982), Rugman

(1976, 1977, 1979) and Agmon and Lessard (1977).117 Building on some earlier work by

Grubel (1968) and Levy and Sarnat (1970), these scholars argued that the MNE oered

individual or institutional equity investors a superior vehicle for geographically diversifying their investment portfolios than did the international equity market. This, in their

view, partly reected the failure of equity markets to eciently evaluate the risks or the

benets of risk diversication, and partly the fact that, compared with their domestic

counterparts, MNEs possessed certain non-nancial advantages that enabled them to

manage the risks of international diversied portfolios more eectively.118

Scholars such as Rugman and Lessard further argued that, given that rms deem it

worthwhile to engage in FDI, the location of that investment would be a function of both

their perception of the uncertainties involved and the geographical distribution of their

existing assets. In the absence of country-specic hazards (foreign exchange risk, political and environmental instability, and so on) rms would simply equate the returns earned

on their assets in dierent countries at the margin, even if this meant concentrating these

assets in only one country. However, it was likely that the uncertainty attached to the

returns would vary with the amount and concentration of assets and this would aect the

geographical distribution of their foreign investments. In a later contribution, Rugman

(1980) acknowledged that the risk diversication hypothesis was best considered as a

special case of a more general theory of international market failure, based upon the

desire and ability of MNEs to minimise cross-border production and transaction costs.

Two related, but somewhat dierent questions emerged regarding risk diversication.

One was whether the prot performance of multinationals on a risk-adjusted basis was

superior to that of domestic rms; the other was the extent to which investing in an MNE

might serve as a substitute for an internationally diversied portfolio of assets. At the

time, empirical research seemed to support the idea that investors did recognise the

benets of diversication provided by MNEs (Agmon and Lessard, 1977). Rugman

(1979) also found that the variance of US corporate earnings in the 1960s was inversely

related to the ratio of their foreign to domestic operations; while Michel and Shaked

(1986) later demonstrated that MNEs were less likely to become insolvent than were

domestic corporations. They also discovered that, while domestic rms sometimes

recorded superior risk-adjusted market performances, MNEs were likely to benet from

lower systematic risk (beta). Kim and Lyn (1986) showed that shareholders paid a

Theories of foreign direct investment

91

comparatively recently that the relationship has been systematically explored using

macroeconomic data. For example, Froot and Stein (1991) presented a model in which

currency movements were shown to aect the geography of MNEs by altering the relative wealth of countries; and demonstrated a signicant negative correlation between the

value of the US dollar and the propensity of foreign rms to invest in the US in 197387.

However, earlier writers, such as Cushman (1985) and Culem (1988), argued that,

rather than reecting relative wealth, exchange rate movements mirrored changes in

relative real labour costs, and it was these that determine FDI. In a test of these alternative propositions, Klein and Rosengren (1994) found that the correlation between the

exchange rate and US inbound direct investment during the 1980s supported the former

rather than the latter hypothesis. Another study exploring the impact of exchange rates

and their volatility on both inward and outward investment is that by Grg and Wakelin

(2002). Using data on FDI (aliate sales) in the US in the 198395 period, they found no

eect for exchange rate variability (risk), but they did discover a positive relationship

between outward investment and host currency appreciation. However, they also found a

negative relationship between inward investment and dollar appreciation, which though

conrming the earlier ndings by Froot and Stein (1991), contradicted their own earlier

research on outward investment. Put very simply, they found that in a period of a generally depreciating dollar, both inward and outward investment increased in a similar

manner.

Such results cast doubt on the previous studies which considered only unidirectional

investment, since cross-investment both between countries and within industries characterises much of FDI.123 The results also depend on whether one focuses on the initial

investment outlay (in which case exchange rates may aect its timing), or on the expected

income stream from any FDI, in which case expectations about future exchange rates are

critical. Furthermore, the extent to which the output is intended to be exported or sold in

the local market may introduce another currency into the equation.

Another way of viewing the inuence of exchange rates on irreversible investments

under uncertainty is within a real options framework.124 In this framework, FDI consists

of a sequence of decisions to invest or to wait, where increased uncertainty (for example,

exchange rate volatility) increases the value of the option to wait. Using real options reasoning, Campa (1993) concluded that exchange rate volatility had a signicant negative

eect on inward investment to the US in the wholesale sector in the 1980s. Other studies

that have focused on the exibility of MNEs in response to changes in exchange rates

include that by Kogut and Chang (1996), who discovered that in addition to being

inuenced by previous investment, Japanese investment to the US was sensitive to changes

in the exchange rate, and that by Rangan (1998), who found that MNEs adjusted their

mix of inputs in response to changes in exchange rates, although to a lesser extent than

might have been expected.

The behavioural theory of the Uppsala school

One of the rst evolutionary models of the internalisation process of rms was that of

Johanson and Vahlne (1977, 1990). Essentially the model predicted increasing resource

commitment to foreign markets over time as a result of organisational learning and the

accumulation of experience. It also predicted that, provided it was economic to do so,

rms would diversify their investments into countries with progressively higher levels of

Theories of foreign direct investment

93

Indeed, built into a model of gradual learning is the idea that the increasing resource

commitment predicted by the model is likely to have less inuence the more information

and experience the rm acquires in the marketplace (Forsgren, 1989). This would make

the process model of internationalisation more applicable to initial internationalisation,

but less to subsequent investments by established multinationals (Kogut, 1983; Barkema

et al., 1996). We also think that the Uppsala model might be particularly suited to explaining the internationalisation of relatively small and inexperienced rms from developing

countries, whose ability to learn via imitation or observation is limited, and who might

lack the resources to undertake asset-seeking M&As (Lundan and Jones, 2001).

One of the main limitations of the various versions of the Uppsala model was that they

largely conned their attention to explaining market, and some subsequent horizontal

eciency-seeking, FDI. It is dicult to see, for example, how the model can explain the

current growth of Chinese FDI in oil exploration in Angola, or the relocation of routine

oce operations from the UK to India. Nor can it easily account for much of the assetaugmenting FDI now occurring particularly by way of M&As. In other words, its contribution as a general evolutionary theory of internationalisation is somewhat decient.

Such a theory, which IB scholars have still not fully addressed, had to wait on the classic

work of Nelson and Winter (1982), to which we shall give some attention later in this

chapter.

4.3

GENERAL EXPLANATIONS OF MNE ACTIVITY

By the mid-1970s, it was becoming increasingly clear that none of the theories so far put

forward to explain the foreign activities of MNEs could claim to explain all such activities, and that most were not trying to answer the same questions. Of all the explanations,

Hymers original thesis and his 1968 article oered the most promise as a general paradigm, although those parts of it, to which later researchers were to give the most attention, were primarily concerned with identifying the reasons why some rms, and not

others, engaged in foreign production, rather than why cross-border value-added activities were organised in one way rather than in another.

In the mid-1970s, three attempts were made to oer more holistic explanations of the

foreign activities of rms, each of which has attracted widespread attention in the literature. Each uses a dierent unit of analysis; two are quite similar in approach, but the third

is very dierent. These are, respectively, the internalisation theory of the MNE, the eclectic paradigm of international production and the macroeconomic theory of FDI.

4.3.1

Internalisation Theory

Internalisation theory is essentially directed to explaining why the cross-border transactions of intermediate products are organised by hierarchies rather than determined by

market forces. It was rst put forward in the mid-1970s by a group of Swedish, Canadian,

British and US economists working largely independently of one another.129 Its basic

hypothesis is that multinational hierarchies represent an alternative mechanism for coordinating related value-added activities across national boundaries to that of the market;

and that rms are likely to engage in FDI whenever they perceive that the net benets of

Theories of foreign direct investment

95

However, viewing the growth of the rm as a time-related process, the legitimacy of this

assumption is questionable. For a rms current core competences, for example, its innovatory strengths, systemic organisational skills, marketing strategy, institutional form,

executive development or its ability to raise and manage nance capital, are the outcome

of past decisions which, at the time they were taken, were endogenous to the rm. Here,

once again, strategic considerations enter the picture (Buckley, 1991). We shall give more

attention to this point in the nal sections of this chapter.

4.3.2

The Eclectic or OLI Paradigm

The eclectic paradigm seeks to oer a general framework for determining the extent and

pattern of both foreign-owned production undertaken by a countrys own enterprises, and

that of domestic production owned or controlled by foreign enterprises. Unlike internalisation theory, it does not purport to be a theory of the MNE per se, but rather a paradigm which encompasses various explanations of the activities of enterprises engaging in

cross-border value-adding activities (Dunning, 2001a). Nor is it a theory of foreign direct

investment in the Aliber sense of the word, as it is concerned with the foreign-owned

output of rms rather than the way that output is nanced. At the same time, it accepts

that the propensity of rms to own foreign income-generating assets may be inuenced

by nancial and/or exchange rate variables. Finally, the eclectic paradigm addresses itself

primarily to positive rather than normative issues. It prescribes a conceptual framework

for explaining what is, rather than what should be, the level and structure of the foreign

value activities of enterprises.

The theory of MNE activity stands at the intersection between a macroeconomic

theory of international trade and a microeconomic theory of the rm. It is an exercise in

macro resource allocation and organisational economics; and in its dynamic form, in evolutionary economics. The eclectic paradigm starts with the acceptance of much of traditional trade theory in explaining the spatial distribution of some kinds of output (which

might be termed HeckscherOhlinSamuelson (HOS) output). However, it argues that,

to explain the ownership of that output and the spatial distribution of other kinds of

output which require the use of resources, capabilities and institutions that are not equally

accessible to all rms, two kinds of market imperfection must be present. The rst is that

of structural market failure which discriminates between rms (or owners of corporate

assets) in their ability to gain and sustain control over property rights or to govern multiple and geographically dispersed value-added activities. The second is that of the intrinsic or endemic failure of intermediate product markets to transact goods and services at

a lower net cost (or higher net benet) than those which a hierarchy might incur (or

achieve).

Such variables as the structure of markets, transaction costs and the managerial strategy of rms then become important determinants of international economic activity. The

rm is no longer a black box; nor are markets the sole arbiters of transactions. Both the

geographical distribution of natural and created factor endowments, and the modality of

economic organisation, are relevant to explaining the structure of trade and production.

Moreover, rms dier in organisational systems, innovatory and institutional abilities,

and in their appraisal of and attitude to commercial risks; and, indeed, in their strategic

response to these (and other) variables. This framework is no less applicable to explaining

Theories of foreign direct investment

97

of international trade theory to incorporate trade in intermediate products, allowing for

the mobility of at least some resources, would be sucient. On the other hand, attempts

to explain patterns and levels of MNE activity without taking account of the distribution of L-bound endowments and capabilities are like throwing the baby out with the

bathwater!

We have argued that the failure of the factor endowment approach to explain international production completely or, in some cases, even partially, arises simply because it

predicates the existence of perfect markets both for nal and intermediate goods. In neoclassical trade theory, this leads to all sorts of restrictive assumptions, such as atomistic

competition, equality of production functions, the absence of risk and uncertainty and,

implicitly at least, that technology is a free and instantaneously transferable good between

rms and countries. Since the 1950s, economists have grappled to incorporate market

imperfections into trade theory but, in the main, their attention has been directed to the

nal rather than the intermediate goods markets. Partly because of this, little attention

has been paid to the organisation of production and transactions across, or indeed within,

national boundaries. Exceptions have included the work of Batra and Ramachandran

(1980), Markusen (1984, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2002b), Helpman and Krugman (1985), Ethier

(1986), Horstmann and Markusen (1987, 1989, 1996), Gray (1994, 1999), Ethier and

Markusen (1996) and Markusen and Venables (1998, 2000). In situations where rms

have some locational choice in the production of intermediate products, this is generally

assumed to inuence their export versus licensing decision, rather than their export versus

foreign production decision.131

We have suggested that the lack of interest by traditional trade economists with ownership or governance questions arises because they have tended to assume again implicitly rather than explicitly that rms engage in only a single value-added activity. The

eect on trade patterns of the vertical integration or horizontal diversication of rms or

their reaction to uncertain markets or government intervention is rarely discussed in the

literature.132 Since the option of internalising domestic markets for intermediate products

within a country has not generally interested trade economists, it is hardly surprising that

they have been relatively unconcerned with issues of international production. Yet the

unique characteristics of the MNE is that it is both multi-activity and engages in the internal transfer of intermediate products across national boundaries. To an extent, the latter

aspect is present in the work of Markusen (2001) who has incorporated MNEs into a twosector, two-country two-factor general equilibrium model. A key feature of this model is

that MNEs are intensive in their use of knowledge-based assets, and that knowledge is a

joint input or a public good within the rm.

Indeed it is the dierence between domestic and international market failure that distinguishes a multinational from a uninational multi-activity rm. It is the inability of the

market to organise a satisfactory deal between potential contractors and contractees of

intermediate products, and to deal with the implications of increasing returns to scale,

that explains why one or the other should choose the hierarchical rather than the market

route for exploiting dierences in L-specic assets between countries. It is the presence of

structural and cognitive market failure that causes rms to pursue dierent strategies

towards the exploitation of the O and L assets available to them.

Several types of market failure are identied in the literature by such scholars

as Buckley and Casson (1976, 1985, 1998), Casson (1979, 1982b, 1985, 1987), Teece

Theories of foreign direct investment

99

It is these and other market deciencies which may cause enterprises, be they uninational or multinational, to diversify their value-adding activities, and, in so doing, realign

their ownership and organisation of these activities. They do so partly to maximise the

net benets of lower production or transaction costs arising from common governance,

and partly to ensure that they gain the maximum economic rent (discounted for risk) from

the O advantages they possess. We shall refer to such perceived advantages of hierarchical

control as internalisation (I) advantages. Again, the only dierence between the actions

of multinational and uninational producers in this respect are the added dimensions of

market failure when a particular transaction or diversication of economic activity is

undertaken across national borders, for example, those arising from exchange and political risks, increased information asymmetry and institutional, social and environmental

dierences. Moreover, market failure may vary according to the characteristics of the

parties engaging in the transactions. Here, too, country-specic factors may enter the

equation. Returning to our parallel between rms engaged in international trade and

international production, it is quite possible that while both may engage in exactly the

same value-added activities, the former will do so within a single country and export their

nal products, whereas the latter will locate at least part of their production outside their

national boundaries.

The distinctive characteristic of MNE activity is, then, that it marries the cross-border

dimension of value-added activities of rms with the common governance of those activities. While the former draws upon the economics of the spatial distribution of immobile

resources and the theory of market structures to explain the location of production independently of its ownership, the theory of market failure helps to explain the organisation

and ownership of production independently of its location. The precise form and pattern

of the resulting international production will then be a function of the conguration of

the O-specic assets of rms and the L-specic assets of countries, and the extent to which

rms perceive that they (rather than markets) can better organise and coordinate these

O and L assets. Given these variables, it will also depend upon the strategic options open

to rms and how they evaluate the consequences of these options.

The main tenets of the paradigm

The principal hypothesis on which the eclectic paradigm of international production is

predicated is that the level and structure of a rms foreign value-adding activities will

depend on four conditions being satised. These are:

1.

2.

The extent to which it possesses unique and sustainable ownership-specic (O) advantages vis--vis rms of other nationalities, in the servicing of particular markets or

groups of markets. These O advantages largely take the form of the privileged possession of or access to intangible assets, including institutions, and those which arise

as a result of the common governance and coordination of related cross-border

value-added activities. These advantages and the use made of them (see 2 and 3

below) are assumed to increase the wealth-creating capacity of a rm, and hence the

value of its assets.133

Assuming that condition (1) is satised, the extent to which the enterprise perceives

it to be in its best interest to add value to its O advantages rather than to sell them, or

their right of use, to independent foreign rms. These advantages are called market

Theories of foreign direct investment

BOX 4.1

101

THE ECLECTIC (OLI) PARADIGM OF

INTERNATIONAL PRODUCTION

Ownership-specic Advantages (O) of an Enterprise of one Nationality (or

Afliates of Same) over Those of Another

(a)

Property rights and/or intangible asset advantages (Oa)

The resource (asset) structure of the rm. Product innovations, production

management, organisational and marketing systems, innovatory capacity,

noncodiable knowledge; accumulated experience in marketing, nance,

etc. Ability to reduce costs of intra- and/or inter-rm transactions (also inuenced by Oi).

(b) Advantages of common governance, that is, of organising Oa with complementary assets (Ot)

(i) Those that branch plants of established enterprises may enjoy over de

novo rms. Those resulting mainly from size, product diversity and

learning experiences of enterprise (e.g., economies of scope and specialisation). Exclusive or favoured access to inputs (e.g., labour, natural

resources, nance, information). Ability to obtain inputs on favoured

terms (e.g., as a result of size or monopsonistic inuence). Ability

of parent company to conclude productive and cooperative interrm relationships. Exclusive or favoured access to product markets.

Access to resources of parent company at marginal cost. Synergistic

economies (not only in production, but in purchasing, marketing,

nance, etc. arrangements).

(ii) Which specically arise because of multinationality. Multinationality

enhances operational exibility by offering wider opportunities for

arbitraging, production shifting and global sourcing of inputs. More

favoured access to and/or better knowledge about international markets

(e.g., for information, nance, labour, etc.). Ability to take advantage of

geographic differences in factor endowments, government regulation,

markets, etc. Ability to diversify or reduce risks. Ability to learn from

societal differences in organisational and managerial processes and

systems (also inuenced by Oi).

(c) Institutional assets (Oi)

The formal and informal institutions that govern the value-added processes

within the rm, and between the rm and its stakeholders. Codes of

conduct, norms and corporate culture; incentive systems and appraisal;

leadership and management of diversity.

Location-specic Factors (L) (These May Favour Home or Host Countries)

Spatial distribution of natural and created resource endowments and markets.

Input prices, quality and productivity (e.g., labour, energy, materials, components, seminished goods).

Theories of foreign direct investment

103

considering them separately. Certainly the location and mode of foreign involvement are

two quite distinct decisions which a rm has to take, even though the nal decision on

where to locate its production will itself depend on the extent and characteristics of its

O advantages (including those of its aliates), and the extent to which it perceives that

that location might help it to internalise intermediate product markets better than

another. It may also depend on the extent to which, as a result of any bargaining power

it may have, for example vis--vis a foreign government, it is able to raise its O advantages

or the advantages of the country in which it is contemplating an investment (Grosse and

Behrman, 1992).135 Take also the distinction between O and I advantages. O advantages

may be internally generated (for example, through product diversication or innovation)

or acquired (for example, through M&As or via contractual agreements with other enterprises). If accessed, for example, by way of a purchase (be it domestic or foreign) of

another enterprise, the presumption is that this will add to the acquiring rms O advantages vis--vis those of its competitors. Elsewhere (Dunning, 1988a) we have argued that

it is useful to distinguish between the capacity to organise value-added activities in a particular way and the willingness to opt for one mode of organisation rather than another.

We have suggested that the eclectic paradigm oers the basis for a general explanation

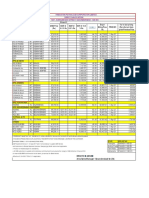

of international production. We illustrate this point by reference to Table 4.1 which relates

the main types of foreign activities by MNEs, set out in Chapter 3, to the presence or

absence of the OLI advantages underpinning these activities. Such a matrix can be used

as a starting-point for an examination of both the industrial and geographical composition of FDI.

In seeking to test the kind of hypotheses implied in Table 4.1, it is useful to distinguish

between three contextual or structural variables that will inuence the OLI conguration

aecting any MNE activity. These are rst those which are specic to particular countries

(or regions); second those which vary according to particular types of activities undertaken by rms; and third those which are specic to particular rms. In other words, the

propensity of enterprises of a particular nationality to engage in FDI will vary according

to the economic-, institutional- and cultural-specic characteristics of their home countries, and those of the country(ies) in which they propose to invest, the range and types of

products (including intermediate products) they intend to produce, and their underlying

management and organisational strategies. Some of these characteristics are set out in

Table 4.2.

Combining Box 4.1 and Table 4.1, as well as Table 5.1 in the following chapter, we have

the core of the eclectic paradigm, which, we believe, oers a rich conceptual framework

for explaining not only the level, form and growth of MNE activity, but the way in which

such activity is organised. Furthermore, as Parts III and IV will seek to demonstrate, the

paradigm oers a robust tool for analysing the role of FDI as an engine of growth, development and structural change; for predicting the economic consequences of MNE activity for the countries in which it operates; and for evaluating the extent to which the policies

of home and host governments are likely both to aect and be aected by that activity.

The eclectic paradigm and other explanations of MNE activity

What, then, is the unique value of the eclectic paradigm? The paradigm avers that, given

the distribution of specic assets, enterprises that have the most pronounced O advantages and perceive they can best exploit these by combining them with others in a foreign

105

To strengthen global

innovatory or

production

competitiveness;

to gain new product

lines or markets

Economies of

common governance;

improved competitive

or strategic

advantages; to reduce

or spread risks

Any of rst three that

oer opportunities for

synergy with existing

assets

Strategic asset

seeking

Any of rst three that

oer technology,

organisational, and other

assets in which rm

is decient

As part of regional

or global product

rationalisation

and/or to gain

advantages of

process

specialisation

As above, but also access (a) Economies of product (a) As for second

to markets; economies

or process specialisation

category, plus

of scope, geographical

and concentration

gains from

diversication and/or

(b) Low labour costs;

economies of

clustering, and

incentives to local

common

international sourcing

production by host

governance

of inputs

governments; a

(b) The economies of

favourable business

vertical integration

environment

and horizontal

diversication

Eciency

seeking

(a) of products

(b) of processes

Knowledge-intensive

industries that record a

high ratio of xed to

overhead costs and

which oer substantial

economies of scale,

synergy or market

access

(a) Motor vehicles,

electrical appliances,

business services,

some R&D

(b) Consumer

electronics,

textiles and clothing,

pharmaceuticals

107

Internalisation Government intervention and extent to which

policies encourage MNEs to internalise

cross-border transactions; government policy

towards mergers; dierences in market

structures between countries with respect to

transaction costs, enforcement of contracts,

buyer uncertainty etc.; adequacy of

technological, educational, communications,

and institutional infrastructure in host countries,

and their ability to absorb contractual

resource transfers

Extent to which vertical or horizontal

integration is possible/desirable

(e.g. need to control sourcing of

inputs or markets); extent to which

internalising advantages can be

captured in contractual agreement

(cf. early and later stages of

product cycle); use made of

ownership advantages; extent to

which local rms have complementary

advantages to those of foreign rms;

extent to which opportunities for

output specialisation and international

division of labour exist

Organisational and control

procedures of the enterprise;

attitudes to growth and

diversication (e.g. the boundaries

of a rms activities); attitudes

towards subcontracting and

contractual ventures such as

licensing, franchising, technical

assistance agreements; extent of

which control procedures can be

built into contractual agreements

Theories of foreign direct investment

109

At the same time, the main dierence between the determinants of intra-national and

international production lies in the particular economic, political, institutional and cultural characteristics of separate sovereign states (Behrman and Grosse, 1990; Grosse,

2005b). Any theory of MNE activity must then seek to identify and evaluate those OLI

advantages which specically arise from foreign production; and how the strategic

response of rms to these advantages might dier because they are operating within and

between dierent environments. For example, why do US auto aliates in some countries

buy out a higher proportion of their components than in others? Why do airline and mail

order rms prefer to establish call centres in India rather than (say) Colombia? What are

the particular common governance advantages which arise by producing in dierent currency areas? What is the role of government regulation in aecting the choice between

foreign and domestic investment? Why, in some sectors, do state-owned MNEs tend to be

more active than in others?

Finally, we would observe that the various components of the eclectic paradigm are

similar (though rarely identical) to those used by scholars interested in explaining the

globalisation of markets and production. To give just one example, the O advantages of

the paradigm embrace the competitive advantages of rms as identied by Michael Porter

in his various studies (Porter, 1980, 1985, 1986). However, we prefer our nomenclature, as

a rm may possess intangible assets which are better described as monopolistic rather

than competitive. An exclusive access to a critical raw material is one such case in point.

Similarly, Porters diamond of competitive advantages (Porter, 1990) oers a useful

framework for analysing the interaction between some of the main L-specic assets of

countries, while his analysis of the factors inuencing the extent to which an enterprise

coordinates its value activities across national boundaries (that is, the way it utilises its

I advantages) draws heavily on the work of internalisation scholars.

In the course of this volume, we shall not hesitate to make use of the work of Porter,

and that of several other scholars from various disciplines as and when it helps to illuminate our understanding of the internationalisation of economic activity, and its impact

on the competitiveness of nation states. Chapter 10, in particular, will set forth a general

model of the interaction between FDI, asset accumulation and economic development,

which is eclectic both in its approach and its sources of inspiration.

4.3.3

A Macroeconomic Approach to Understanding MNE Activity

Both the internalisation and eclectic paradigms of international production are essentially microeconomic or behavioural explanations in the sense that they attempt to identify and evaluate the variables that determine the foreign activities of particular rms or

groups of rms. Using the same data to explain the determinants of a countrys propensity to engage in foreign production is legitimate only in so far as the actions of individual producers do not aect the value of the variables that they the producers take to

be endogenous. After this point, the scholar not only has to move from a partial to a

general equilibrium perspective, but also has to reappraise the kind of questions he or she

seeks to answer. Thus, rather than trying to explain why rms choose to undertake a particular value-added activity in a particular country, the macro economist is more interested in explaining which activities of rms are best undertaken in particular countries.

In the former case, a comparison is made between the absolute costs and benets of

Theories of foreign direct investment

111

conditions of market failure, multinational hierarchies may improve rather than worsen

such an allocation. The means by which this is accomplished, which include geographical

diversication, exploitation of the economies of joint supply, better commercial intelligence and the avoidance of costs of enforcing property rights, have been well spelled out

by Gray (1982, 1999).

In one of his later writings, Kojima (1992) acknowledges that MNEs may sometimes

need to internalise intermediate product markets to promote their economic eciency.

However, rather than seeking to identify and evaluate the signicance of the particular

forms of market failure likely to determine dierent kinds of FDI, he chooses to analyse

the circumstances in which rms will use internal or external markets to optimise their

transactions of intermediate products. He nds that the key determinant of the sourcing strategy of rms lies in the relative strength of the internal and external economies

facing the rms, which, in turn, reect the technical characteristics of their production

functions.138

4.4

A NOTE ON AN EVOLUTIONARY APPROACH TO

EXPLAINING MNE ACTIVITY

Looking rst at the simple dynamics of MNE activity in terms of the eclectic paradigm,

a rms strategy acts as a dynamic force that bridges its internationalisation posture at

dierent periods of time. The argument runs as follows. At any given moment of time, a

rm is faced with a conguration of OLI variables and strategic objectives, to which it will

respond by engaging in a variety of actions relating to technology creation, market

positioning, inter-rm networking, organisational structure, political lobbying, intrarm pricing and so on. These actions, together with changes in the value of the exogenous variables it faces, will inuence its global competitive position, and hence its OLI

conguration at a future date. An explanation of the strategy of MNEs then becomes

central to an understanding of the dynamics of international production. Not only will

the kind of rm-specic O advantages set out in Table 4.2 be important, but also how

the rm perceives that its competitors will react to any change in its own internationalisation strategy. Here economic and behavioural theories of the rm interact with

each other.139

In a seminal article, Kogut (1983) persuasively argued that, although the possession of

superior intangible assets may give rise to the initial act of foreign production, once established abroad the advantages of multinationality per se, that is, those gained from the

spreading of environmental risks and the common governance of diversied activities in

dispersed locations, become more signicant. In later papers, Kogut has also related the

international strategy of MNEs to the source of these sequential advantages140 and to

their learning experiences in coordinating domestic and foreign production (Kogut, 1991;

Kogut and Kulatilaka, 1994, 2001).

This brings us to the contribution of evolutionary economics to our understanding of

MNE activity. To what extent have there been attempts to evaluate the extent to which the

internationalisation of production is linked to the willingness and capacity of rms to

accumulate, integrate and control O advantages across national borders? Up to now, the

main focus has been on the accumulation of technological assets by MNEs, although we

Theories of foreign direct investment

113

path-dependent process, which evolutionary theory is better able to understand and evaluate, than traditional neo-classical models (Nelson and Pack, 1999).

The chapters in Part II will discuss in detail how asset-seeking motivations aect the

sequencing of investment, as well as the coordination of activities within the internal and

external value-added network of the MNE.142 For now, we shall simply note that assetacquiring or -augmenting investment is of critical importance to understanding the

evolution of the modern MNE, and that such activity also lies at the core of two new theoretical approaches, namely the resource- and knowledge-based theories of the rm,

which we shall discuss in relation to the eclectic paradigm in Chapter 5.

Finally, at a macroeconomic level, the dynamics of how the changing O advantages of

rms and the L advantages of countries interact to explain the patterns of inward and

outward MNE activity in a particular country have been explored by the investment

development path (IDP). The IDP model was initially put forward by Dunning (1981,

1986a, 1988a), and developed further by Dunning and Narula (1996b) and Narula (1996)

as a means for describing and analysing the underlying reasons for FDI-induced restructuring at dierent stages of development. The basic hypothesis is that, as a country develops, the conguration of the OLI advantages facing foreign-owned rms that might invest

in that country and of its own rms that might invest overseas, changes, and that it is possible to identify the determinants for the change as well as its eect on the trajectory of

development. The latest thinking on the IDP set out in Dunning et al. (2001) attempts to

incorporate both trade and industrial structural change into its analysis. The IDP will be

discussed further in Chapter 10. For the moment, we may think of it as an example of

how MNE activity may aect the evolution of a countrys growth path.

4.5

ISSUES RESOLVED AND UNRESOLVED BY RECEIVED

THEORY

In this chapter, we have described the evolution of the theory of international production

over the past four decades. It may be interesting to note, as Dunning (2004a) has recently

done, that the contribution of British (and other European) scholars to the theory of the

MNE is considerable, as is their contribution to the history of the MNE and cross-border

investment, which is reviewed in the next chapter. However, in Part II, as we move inside

the rm in a quest to understand and evaluate the structural and strategic transformations of the MNE, the contribution of North American scholars becomes predominant.

While such dierences may be disappearing, particularly with the emergence of new business schools and the increasing mobility of individual scholars across borders, the strong

historical position of American business schools may explain some of these dierences in

focus.

In the early 2000s, we have a galaxy of partial theories that purport to explain particular aspects of FDI and MNE activity, particular kinds of foreign production, and particular behavioural strategies of dierent types of MNEs. Most of these have been tested

empirically; and most have sought to identify either the particular OLI variables aecting

the geographical or industrial distribution of foreign production, or the strategic response

of MNEs to these variables. Surprisingly few have attempted to assess the extent to

which foreign-owned aliates actually do record higher prots than their indigenous

Theories of foreign direct investment

115

much they may demand a re-evaluation of several contextual theories which seek to evaluate the critical OLI variables aecting particular kinds of MNE activities. Similarly,

together with a theory of strategic behaviour, both can satisfactorily identify the reasons

why rms prefer to conclude joint ventures rather than engage in 100%-owned foreign

production. They can even explain the determinants of the locus of control within rms.

However, we and other scholars have identied four other trends in international business

that might require a more fundamental appraisal of existing modes of thought. These

include the continued growth in the importance of (a) cooperative alliances and networks,

(b) international spatial clustering, (c) the quality of relational assets of rms and countries145 and (d) the role of institutions as underpinning the O and I advantages of rms

and the L advantages of locations. Chapter 5 will present our attempt to incorporate these

factors into the eclectic paradigm.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Step by Step Guide To Rebuild Your CreditDokument9 SeitenStep by Step Guide To Rebuild Your CreditAbidemiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Mergers and Acquisitions in Indian Banking SectorDokument49 SeitenMergers and Acquisitions in Indian Banking SectorShafia Ahmad79% (104)

- OpbyccDokument1 SeiteOpbyccUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Case MISCDokument8 SeitenFull Case MISCfitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iqcert International LTD.: Documents Checklist For Grs & RcsDokument3 SeitenIqcert International LTD.: Documents Checklist For Grs & RcsMd. Samirul Islam100% (2)

- 6 Oua de Nota 10Dokument1 Seite6 Oua de Nota 10Alex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sbs Executive Mba: ModulesDokument4 SeitenThe Sbs Executive Mba: ModulesAlex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eye - Ecas Quick GuideDokument6 SeitenEye - Ecas Quick GuideAlex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course 1 - Main Concepts (2) Lmsauth D24d84e0Dokument9 SeitenCourse 1 - Main Concepts (2) Lmsauth D24d84e0Alex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12Xt SystemDokument2 Seiten12Xt SystemAlex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12Xt SystemDokument2 Seiten12Xt SystemAlex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fortune Magazine "Internet Top 40 Under 40" Issue Featuring Jonathan Bates - 1999Dokument1 SeiteFortune Magazine "Internet Top 40 Under 40" Issue Featuring Jonathan Bates - 1999Jonathan Bates100% (1)

- GAP Analysis CZDokument51 SeitenGAP Analysis CZAlex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- C Forecast of The Development of Macroeconomic Indicators 2013 Q2Dokument7 SeitenC Forecast of The Development of Macroeconomic Indicators 2013 Q2Alex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GAP Analysis CZDokument51 SeitenGAP Analysis CZAlex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- OLIMPICI - 2010 - Lista TotalaDokument6 SeitenOLIMPICI - 2010 - Lista TotalaAlex UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vanilla Term Sheet KFT VENDokument11 SeitenVanilla Term Sheet KFT VENsefdeniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2 (PJ)Dokument2 SeitenAssignment 2 (PJ)Nabila Abu BakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Management: 1 Defining Marketing For The 21 CenturyDokument35 SeitenMarketing Management: 1 Defining Marketing For The 21 CenturyRosinta Dwi OktaviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quiz 2.docx Afar 2Dokument2 SeitenQuiz 2.docx Afar 2Ella Turato100% (1)

- Limited Partnership LimDokument4 SeitenLimited Partnership LimLim JOSHUA SAMUELNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service Tax Rules, 1994Dokument75 SeitenService Tax Rules, 1994Gens GeorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nokia Offer Document EnglishDokument106 SeitenNokia Offer Document EnglishsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Economics - Chapter 9Dokument13 SeitenFundamentals of Economics - Chapter 9Alya SyakirahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Taxpayers-Sample ProblemsDokument30 SeitenIndividual Taxpayers-Sample ProblemsexquisiteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deepak Kumar: SkillsDokument4 SeitenDeepak Kumar: SkillsdeepakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Shankara Matt: Cummulative Statement 2017Dokument28 SeitenSri Shankara Matt: Cummulative Statement 2017Vijaya BhaskarNoch keine Bewertungen

- HPCL - PRICE - LIST - EFF-1st April 2021Dokument1 SeiteHPCL - PRICE - LIST - EFF-1st April 2021aee lweNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACCO 420 Post Midterm NotesDokument21 SeitenACCO 420 Post Midterm NotesJane YangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Client MasterDokument1 SeiteClient Masterpauljones7975Noch keine Bewertungen

- State Bank of India (SBI) : Fortune Global 500Dokument14 SeitenState Bank of India (SBI) : Fortune Global 500Varsha RayaluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3 - JNK Case - HWDokument2 SeitenLesson 3 - JNK Case - HWnicholas tanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax and Regulatory: Epc Contracts - Fiscal ScenarioDokument30 SeitenTax and Regulatory: Epc Contracts - Fiscal Scenariopranjal92pandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship Development Class 12 NotesDokument27 SeitenEntrepreneurship Development Class 12 NotesHsnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Future and Option TurnoverDokument4 SeitenFuture and Option TurnoverROHIT GUPTANoch keine Bewertungen

- Finedge Bionic Advisory For A Digital IndiaDokument18 SeitenFinedge Bionic Advisory For A Digital IndiaShankaran RamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategy at Regal MarineDokument7 SeitenStrategy at Regal MarineAnggitaridha SeptirendiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Right To SafetyDokument5 SeitenRight To SafetyAshu BhoirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana - Claim Form: (To Be Completed by The Claimant & Bank)Dokument2 SeitenPradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana - Claim Form: (To Be Completed by The Claimant & Bank)srajan sahu100% (2)

- 13.1 Introduction To The Balance of Payments Answer KeyDokument4 Seiten13.1 Introduction To The Balance of Payments Answer KeySOURAV MONDALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Covid 19 - A Comparative Study of India and GermanyDokument9 SeitenImpact of Covid 19 - A Comparative Study of India and GermanyShipra BaruaNoch keine Bewertungen