Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Nontenure Track Faculty

Hochgeladen von

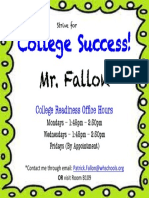

Patrick J. FallonCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Nontenure Track Faculty

Hochgeladen von

Patrick J. FallonCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1

Nontenure-track faculty members face both challenges

and opportunities.

Nontenure-Track Faculty: Rising

Numbers, Lost Opportunities

Kate Thedwall

A history of the professoriate would not be complete without an account of

nontenure-track faculty. Whether these faculty members are referenced

using the terms contingent, part time, contract, adjunct, clinical, research,

visiting, lecturer, or senior lecturer, they constitute a group of faculty who

have lived and worked at the margins of academia for some time.

This chapter discusses the history of the nontenure-track faculty, the

benefits of their appointments, and the challenges and opportunities that

these faculty face. The focus here is on those who are primarily serving as

teachers, as opposed to other roles.

Historical Overview of Faculty Appointments

This discussion of nontenure-track faculty appointments begins with a

historical perspective. Nontenure-eligible faculty have been part of the fabric

of U.S. colleges and universities for well over a century. Following the Civil

War and the passage of the Morrill Land Grant Act (1862), states were

charged with preparing students for roles as leaders and intelligent participants in the U.S. democratic system. At the same time, faculty who earned

doctorates abroad or worked with European researchers began to base their

expectations and culture on a model of the research university originating

in Germany. Much of todays image of the professoriate continues in this

tradition. With the creation of land-grant institutions, the number of

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION, no. 143, Fall 2008 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/he.308

11

12

FACULTY AT THE MARGINS

university faculty members grew exponentially. These faculty became state

government employees and enjoyed the same rights as other state employees.

During these early years of land-grant institutions, faculty began to divide

into ranks. The University of Wisconsin and Cornell University were two

of the first universities to divide faculty into assistant, associate, and full

professor ranks, and these same institutions, according to Gappa, Austin,

and Trice (2007) codified the procedures for advancement in rank and for

the probationary period prior to advancement to tenure (p. 51). Tenure as

we know it became part of the fabric of the academy.

By 1915, the American Association of University Professors was

formed. Faculty at this time argued for the German tradition of the

freedom to study, teach and advance unpopular ideas publicly, and labeled

this academic freedom (Rudolph, 1990, cited in Gappa, Austin, and Trice,

2007, p. 52). Besides academic freedom, Americans added the idea of

continuous employment to protect the idea of freedom of expression and

economic security (Rudolph, 1990). The 1940s Statement on Principles of

Academic Freedom and Tenure articulated these values and was endorsed

by college presidents and learned societies (Euben, 2006). The statement

did not talk about the role of nontenure-track faculty but established the

foundation of tenure-track faculty appointments and their status in

academe.

After World War II, returning soldiers used their government-subsidized

tuition benefits and flooded into American colleges and universities. Besides

subsidizing research, the federal government also assisted new student

college careers by establishing the first federal student aid programs

(Rudolph, 1990). As student enrollment grew 500 percent between 1945

and 1975, the American faculty had indeed reached the golden age (Gappa,

Austin, and Trice, 2007; Cohen, 1998). During these decades, rising enrollments forced administrators to find a way to meet the enrollment numbers

and deal with rising costs. At the same time, faculty unions were becoming

more prevalent following the recessions of the late 1970s and early 1980s,

when faculty salaries were cut or frozen. Administrators faced faculty who

had not had a raise in several years or who actually had their salaries cut.

These administrators still needed to staff class sections and offer senior

faculty, and in some cases, unionized senior faculty, legitimate concessions.

The time had arrived for hard questions. How would colleges and universities stay in the black, keep standards high, and still have classes to

offer? Some institutions, according to Holub (2003), chose to reduce staff,

halt faculty and staff hiring and promote early retirement (p. 3). But the

most lasting solution lay with increasing the employment of part-time

faculty, who worked for lower wages, required little or no professional

development support, and could be hired or released quickly as enrollments

fluctuated (American Association of University Professors, 2003; Meyer,

1998; Baldwin and Chronister, 2001).

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

NONTENURE-TRACK FACULTY

13

It appears most likely that this pattern of employment will continue.

As Jacobs (1998) said in reference to the constraints of economics, personnel, and time, Even this recovering administrator can see the stark reality

that those constraining issues are not transient; they are permanent and

there will never be enough money, time or personnel to eliminate the

problem caused by scarce resources (p. 10).

The Current Situation

The issue of nontenure-track faculty has become a heated one in higher

education (American Association of University Professors, 2003; Albert,

2003). Increasing the employment of nontenure-track faculty answered the

demand for professors but raised the question of whether tenure or tenure-track

status mattered (Ehrenberg and Zhang, 2005). This question still lingers

from the 1970s. Justified, debated, and researched, nontenure-track faculty

currently make up more than 58 percent of university faculty at four-year

colleges and universities (American Association of University Professors,

2006; Baldwin and Chronister, 2001). At public two-year colleges,

nontenure-eligible faculty make up approximately 83 percent of the

teaching faculty (American Association of University Professors, 2006).

Full-time tenured and tenure-track faculty at two- and four-year institutions decreased dramatically from 56.8 percent in 1975, to 41.1 percent

in 1995 to 35.1 percent in 2003 (American Association of University

Professors, 2006). Although the late 1990s brought a reversal of the U.S.

economy, nontenure-track faculty have not been replaced by tenure-track

or tenured faculty. Baldwin and Chronister (2001) suggest that other

external factors have prevented higher education from increasing tenuretrack faculty positions, including losing the publics trust and confidence;

federal policies influencing faculty personnel policies; the high cost of

implementing new technologies; flexibility required for distance education;

increased competition for students from for-profit universities; downsizing

trends and criticisms of tenure. As these factors continue to hold, the reality

appears to be that the traditional employment model for faculty is gone.

Types of Nontenure-Track Faculty

The nontenure-track faculty profile can look very different depending on

college and university type. According to Shavers (2000), Most institutions

label all non-tenurable positions as non-tenure track, from part-time to

full-time, visiting to adjunct and temporary to contingent (p. 112). These

terms represent the names that the American professoriate has come to

accept. However, the 1995 American Association of University Professors

Policy Documents and Reports describes three categories of nontenure-track

faculty:

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

14

FACULTY AT THE MARGINS

1. Renewable appointments. Faculty are contracted for approximately one

or more years. They are told that appointments may be renewed, and

there is no limit on the number of renewals.

2. Limited renewable appointments. Faculty are told that their contract is

for one year only, but can be renewed a certain number of times,

generally between one and three years.

3. Folding chairs. This category characterizes any nontenure-track faculty

whose contract is explicitly terminal. There can be no renewal.

These categories relate to the method of appointment or nonreappointment for all types of nontenure-track faculty, yet they do not explain

the variety of roles that these faculty can hold: clinical faculty, primarily

tasked with program administration and practical education; research

faculty responsible for research productivity; and teaching-focused lecturers,

engaged in undergraduate or graduate teaching. Although the literature

treats each of these appointments together, each appointment type benefits

institutions differently and has its unique challenges and opportunities. The

real challenge is that the number of teaching appointments crowds out the

number of tenure-eligible faculty who are available to do research, teach,

and provide service to the institution. Issues of academic freedom, security,

and equity within the faculty profession are at stake.

Among the chief equity issue across all nontenure-track appointment

types is the lack of benefits and perquisites of tenure-track faculty life. Those

with the most uncertainty are those in folding chair appointments, which

are the least desirable appointments but common. When considering the

vast numbers of contingent, nontenure-eligible faculty in the United States,

those who occupy these positions are often in precarious positions and are

unwilling to cause negative attention due to their position in the institution.

Benefits of Nontenure-Track Appointments

Nontenure-track appointments have benefits not only for institutions at

large but for other stakeholders as well. This section highlights the benefits

of nontenure-track appointments of all types for tenure-line faculty, the

appointees themselves, and the institutions that hire them.

Benefits to Tenure-Track Faculty at Four-Year Institutions. Since

nontenure-track faculty are often employed to teach high-enrollment lowerdivision courses, this arrangement allows tenure-eligible faculty to teach

upper-division and graduate courses, which are often smaller and more

enjoyable to teach (Benjamin, 2003b; Brand, 2002; Cross and Goldenberg,

2002). In exchange for the lighter teaching load for these faculty, institutions are insisting on a higher level of grant activity, publications, and other

forms of creative activity to earn tenure. Often this is a bargain that tenureline faculty are willing to make, since it enables them to attend to the

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

NONTENURE-TRACK FACULTY

15

scholarly work they must produce to receive tenure and other rewards for

research (Meyer, 1998).

Benefits to Nontenure-Track Faculty Themselves. Nontenure-track

faculty also benefit from their work experience. Graduate students can gain

valuable teaching experience as independent course instructors or in

cooperation with a tenure-line faculty member. Nontenure-track faculty

who are professionals employed primarily outside the institution gain

additional income, personal enjoyment, and perhaps some prestige due to

their association with the university or college (Schuster and Finkelstein,

2006; Gappa, Austin, and Trice, 2007). Lecturers who are employed full

time gain access to fringe benefits, a stable salary, and a working situation

that in some cases offers a flexible work schedule, good working conditions,

and access to resources such as the library and other research facilities.

These lecturers may also have access to professional development funds and

activities. In addition, full-time lecturers may be considered for tenure-track

positions as they become available, though their appointment as such is not

guaranteed (Brand, 2002). Practically speaking, however, full-time lecturers

are often employed in positions where there is little chance for advancement

into tenure-track positions, given an institutional bias favoring those from

outside the institution (Gappa, Austin, and Trice, 2007; Brand, 2002). Even

without the chance for advancement, many nontenure-track teaching

faculty believe that their positions enable them to do what they love: teach.

Benefits to Institutions. The primary benefit for all institutions is the

vast economic benefit gained. All institutions hiring nontenure-track faculty

in lieu of tenure-line faculty gain through salary savings (Benjamin, 2003b;

Brand, 2002; Cross and Goldenberg, 2002). Another universal benefit is the

inherent flexibility that nontenure-track appointments offer. This flexibility

manifests itself in a number of ways, which vary depending on institution

type. Particularly when hiring graduate students and contingent, part-time

faculty, institutions gain great flexibility in both hiring decisions (meaning

whom they hire) and the duration of employment. Often these faculty members are hired on an as-needed basis, sometimes only a few days before their

course is set to begin, and with little or no preparation (Gappa, Austin, and

Trice, 2007; Benjamin, 2003b). Contingent faculty can also fill the gap for

tenure-eligible or full-time faculty who cannot fulfill their teaching duties

for a variety of reasons, including course buyouts connected with funded

research or special projects, sabbatical leaves, and family or medical leaves

of absence.

For some contingent faculty who teach one course per term, as well as

full-time lecturers, the employment guarantee is one term or, at most, one

year of stable employment, though this may vary by institution. Folding

chairs, and part-time faculty in particular instances, may be removed from

their teaching responsibilities at almost any time. Even with an oral agreement with a department chairperson or departmental administrator, these

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

16

FACULTY AT THE MARGINS

contingent faculty members can be bumped out of their assigned teaching

slot at the last moment if a tenure-eligible faculty member becomes available

to teach. Related to this institutional benefit of employment flexibility is the

ability to bring in nontenure-track faculty for particular curricular needs

and professional skills without making a long-term commitment.

Full-time nontenure-eligible faculty can often be employed in flexible

roles as well. At some universities, full-time lecturers have primary responsibility for teaching, but also carry an ancillary assignment, such as student

advising, special projects, or other administrative duties. The assumption

of these responsibilities allows tenure-eligible faculty some additional

release time to use for research or other responsibilities.

Benefits to Full-Time Faculty at Two-Year Institutions. At two-year

institutions, nontenure-track faculty are essential to the educational mission

of the institution. Given that the faculty population at these colleges is over

80 percent nontenure-track, tremendous expansions of salary budgets

would be needed to employ full-time faculty. In addition to keeping costs

down, the employment of nontenure-track faculty allows full-time faculty

at these institutions time to engage in university or departmental governance, obtain teaching load reductions, or gain time for service activities.

The literature indicates that two-year colleges often employ nontenure-track

faculty in contingent, part-time appointments in order to staff classes that

require special expertise within the pool of tenure-track faculty (Cross and

Goldenberg, 2002).

Brand (2002) and Benjamin (2003b) also note that hiring nontenuretrack faculty, especially in the role of full-time lecturer, may lower studentfaculty ratios. Brand indicates that a lower student-faculty ratio is correlated

with greater student learning outcomes, an added positive impact.

Challenges and Opportunities

In addition to these many benefits, there are common challenges and opportunities for improvement associated with using nontenure-track faculty

appointments. These have been shown to be operating to some degree

regardless of institutional type.

The literature on faculty appointments is filled with arguments against

the practice of hiring nontenure-track faculty. Benjamin (2003a, 2003b)

asserts that nontenure-track faculty, especially part-time faculty, are in

general less educationally qualified, lower the overall faculty quality, diminish

faculty involvement in student learning, and sustain a two-tiered labor market.

These are serious charges, and they bear exploring. In general, nontenuretrack faculty, particularly part-time and graduate students, are less likely to

have earned a terminal degree (Benjamin, 2003b; Baldwin and Chronister,

2001; Harper, Baldwin, Gansneder, and Chronister, 2001; Shavers, 2000).

Benjamin is strident in his argument that the terminal degree, normally the

doctorate, is the standard qualification of the faculty and must be retained

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

NONTENURE-TRACK FACULTY

17

if overall faculty quality is to be maintained.

Another consequence of an overreliance of nontenure-track faculty is

said to be a lack of focus and attention to student learning. Benjamin

(2003b) uses the National Center for Educational Statistics data from 1999 to

indicate that part-time faculty members spend less than one-half the time

that full-time faculty expend on out-of-class contact with students. Parttime faculty also spend less time in the classroom overall and less time

preparing for class than full-time faculty do (Benjamin, 2003b).

Benjamins points are well taken as general remarks, but seem to apply

mostly to faculty employed part time, regardless of institution type. He

seems not to account for the involvement and impact of nontenure-track

lecturers employed on a full-time basis. As Brand (2002) has argued, fulltime lecturers can strike a balance between the benefits of full-time faculty

on the tenure track and part-time appointments. Full-time lecturers have

primarily teaching but also service responsibilities, and thus are available

for regularly scheduled office hours for academic advising and other

activities that support student learning and engagement

Kavanaugh (2000) also argues that nontenure-track positions are

diminishing the facultys role in institutional governance. He says that these

faculty, particularly part-time and graduate students, are less likely to sustain

institutional commitment to the institution. He points out, As virtual noncitizens within the university community, part-time faculty, graduate student

employees, and non-tenure-track faculty are too often denied the right to

participate in institutional or even departmental governance (p. 27).

Nontenure-track faculty employed on a full-time basis are also disadvantaged regarding the perquisites of faculty life. They are often not paid as

much (Brand, 2002) and often enjoy less prestige than their tenure-track

colleagues (American Association of University Professors, 2006), primarily

because status is associated with research productivity. In essence, tenure-track

faculty who teach and do research believe that their research informs their

teaching and keeps them current in the field. Since lecturers often lack the

doctorate and are less able to engage in scholarly research due to time commitments and student contact hours, they are often viewed as less informed

on cutting-edge developments in their fields and consequently are less credible.

Although nontenure-track appointments now make up a majority of

the faculty, they have very little, if any, role in institutional, and often

departmental, governance (American Association of University Professors,

2006; Brand, 2002). They also often feel that the safety of academic freedom

is unavailable to them. Thus, many nontenure-track faculty are considered

by tenure-track faculty and by themselves to be second-class citizens,

whether by custom or by rule (Harper, Baldwin, Gansneder, and Chronister, 2001).

Careful consideration of the benefits and challenges of the continuing

employment of large numbers of nontenure-track faculty is a pressing task

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

18

FACULTY AT THE MARGINS

for institutions as they plan for the future. Clearly nontenure-track faculty

are here to stay, and stay in large numbers. The questions facing institutions

of higher learning should center around how to acknowledge the benefits

these appointments provide, as well as commit to working through the challenges that face this growing segment of our academy. Now is the time to

address issues of salary, job security, respect, governance, and statusissues

that will influence much about the quality of higher education in the future.

References

Albert, J. (ed.). Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Special Interest Group. Forum, 2003, 1(3),

A1-A16.

American Association of University Professors. Policy Documents and Reports. (8th ed.)

Washington, D.C.: American Association of University Professors, 1995.

American Association of University Professors. Professors of Practice. Academe, 2003,

1(9), 6061.

American Association of University Professors. Trends in Faculty Status, 19752005:

All Degree-Granting Institutions, National Totals. 2006. Retrieved Apr. 12, 2008,

from http://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/9218E731-A68E-4E98-A378-12251FFD38

02/0/Facstatustrend7505.pdf.

Baldwin, R. G., and Chronister, J. L. Teaching Without Tenure: Policies and Practices for

a New Era. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Benjamin, E. How Over-Reliance on Contingent Appointments Diminishes Faculty

Involvement in Student Learning. Peer Review, 2003a, 1(5), 410.

Benjamin, E. (ed.). Exploring the Role of Contingent Instructional Staff in Undergraduate

Learning. New Dimensions in Higher Education, no. 123. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass,

2003b.

Brand, M. Full-Time, Non-Tenure-Track Appointments: A Case Study. Peer Review,

2002, 1(5), 1321.

Cohen, A. M. The Shaping of American Higher Education: Emergence and Growth of the

Contemporary System. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998.

Cross, J. G., and Goldenberg, E. N. Why Hire Non-Tenure-Track Faculty? Peer Review,

2002, 1(5), 2528.

Ehrenberg, R. G., and Zhang, L. Do Tenured and Tenure-Track Faculty Matter?

Journal of Human Resources, 2005, 40, 647659.

Euben, D. Legal Contingencies for Contingent Professors. 2006. Retrieved Jan. 31,

2007, from http://chronicle.com/weekly/v52/i41/41b0080.

Gappa, J. M., Austin, A. E., and Trice, A. G. Rethinking Faculty Work: Higher Educations

Strategic Imperative. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007.

Harper, E. P., Baldwin, R. G., Gansneder, B. G., and Chronister, J. L. Full-Time Women

Faculty off the Tenure Track: Profile and Practice. Review of Higher Education, 2001,

3(24), 237257.

Holub, T. Contract Faculty in Higher Education. 2003. Retrieved Apr. 12, 2008, from

http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/

1b/8f/fa.pdf.

Jacobs, F. Using Part-Time Faculty More Effectively. In D. W. Leslie (ed.), The

Growing Use of Part-Time Faculty: Understanding Causes and Effects. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass, 1998.

Kavanaugh, P. A Vision of Democratic Governance in Higher Education: The Stakes of

Work in Academia. Social Policy, 2000, 4(30), 2430.

Meyer, K. Faculty Workload Studies: Perspectives, Needs and Future Directions. ASHEERIC Higher Education Reports, no. 26. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 1998.

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

NONTENURE-TRACK FACULTY

19

Rudolph, F. The American College and University: A History. Atlanta: University of

Georgia Press, 1990.

Schuster, J. H., and Finkelstein, M. J. The American Faculty: The Restructuring of Academic

Work and Careers. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Shavers, F. L. Academic Ranks and Titles of Full-Time Non-Tenure-Track Faculty. In

C. A. Trower (ed.), Policies on Faculty Appointment: Standard Policies and Unusual

Arrangements. Bolton, Mass.: Anker, 2000.

KATE THEDWALL is the director of the Gateway to Graduation program and senior

lecturer in the Department of Communication Studies at Indiana University

Purdue University Indianapolis. She also is a doctoral student at the Indiana

University School of Higher Education.

NEW DIRECTIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION DOI: 10.1002/he

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Introduction To People Management LilyDokument16 SeitenIntroduction To People Management LilyAlexandru NicolaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM Nordstrom CaseDokument6 SeitenHRM Nordstrom CaseAna Matias100% (1)

- Topics For HR Research ReportDokument2 SeitenTopics For HR Research Reportarchana_anuragiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eco Camp 2019 Registration FormDokument2 SeitenEco Camp 2019 Registration FormPatrick J. FallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- F202 Signs PDFDokument1 SeiteF202 Signs PDFPatrick J. FallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eco Camp Voice Ad 2019Dokument1 SeiteEco Camp Voice Ad 2019Patrick J. FallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- College Life Poster 2018-19Dokument1 SeiteCollege Life Poster 2018-19Patrick J. FallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Noam Osband: Wednesday, March 25, 2015 7:00pm Midtown Student Center TheaterDokument1 SeiteNoam Osband: Wednesday, March 25, 2015 7:00pm Midtown Student Center TheaterPatrick J. FallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Books For Success PublicityDokument1 SeiteBooks For Success PublicityPatrick J. FallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Operation Jungle Red FlyerDokument1 SeiteOperation Jungle Red FlyerPatrick J. FallonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2-Job Analysis NotesDokument26 Seiten2-Job Analysis Notesmusiomi2005Noch keine Bewertungen

- HRM BBA Lecture 1Dokument35 SeitenHRM BBA Lecture 1navin9849Noch keine Bewertungen

- Performance ManagementDokument8 SeitenPerformance ManagementKJuneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Auditing Arens Chapter 20Dokument30 SeitenAuditing Arens Chapter 20MARLINNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study of Personnel Management With Special Emphasis On Performance Appraisal System in Crompton GreavesDokument8 SeitenA Study of Personnel Management With Special Emphasis On Performance Appraisal System in Crompton GreaveskharemixNoch keine Bewertungen

- Memo - AttendanceDokument1 SeiteMemo - AttendanceDayneisha Blueitt-GonsalvesNoch keine Bewertungen

- St. Luke's Medical Center Employees Association Vs NLRCDokument1 SeiteSt. Luke's Medical Center Employees Association Vs NLRCBen DangcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Manager's Role in Employee RetentionDokument18 SeitenThe Manager's Role in Employee RetentionRomer OgnitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11 - Human Resource ManagementDokument31 SeitenChapter 11 - Human Resource ManagementTasya DaliantyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Staff Turnover CalculatorDokument25 SeitenStaff Turnover CalculatorAmjad AbroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artist Independent Contractor AgreementDokument4 SeitenArtist Independent Contractor AgreementMission3DNoch keine Bewertungen

- Onboarding Checklist PDFDokument1 SeiteOnboarding Checklist PDFL1 Support Team - BWANoch keine Bewertungen

- Procedure of Punishment For Conviction and MisconductDokument4 SeitenProcedure of Punishment For Conviction and MisconductAnonymous 1LcDs26jL5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jamieque David Mccullough CDokument3 SeitenJamieque David Mccullough Ccrippa cripNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appointment LetterDokument24 SeitenAppointment LetterBhagat BhandariNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRM ChecklistsDokument3 SeitenCRM ChecklistsalbertoprbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Labor: Nov05-1Dokument1 SeiteDepartment of Labor: Nov05-1USA_DepartmentOfLaborNoch keine Bewertungen

- CreateTable in SQLDokument15 SeitenCreateTable in SQLMirza AlibaigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing Performance AppraisalDokument6 SeitenWriting Performance AppraisalBen JasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business English Placement TestDokument8 SeitenBusiness English Placement TestAllan BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Satisfaction and Workplace RelationshipsDokument6 SeitenJob Satisfaction and Workplace RelationshipsSaravana KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Changing Nature of Human Resource ManagementDokument10 SeitenChanging Nature of Human Resource ManagementAndie WawaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposal ForDokument18 SeitenResearch Proposal ForAnonymous mqr6y1i100% (1)

- RedBus Ticket 29209964Dokument1 SeiteRedBus Ticket 29209964Ankit KhambhattaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rewards & RecognitionDokument21 SeitenRewards & RecognitionIndrajeet SukateNoch keine Bewertungen

- WPMDokument3 SeitenWPMDebanjan DebNoch keine Bewertungen

- 66-1 Business Studies PDFDokument15 Seiten66-1 Business Studies PDFKAUSHIK DEYNoch keine Bewertungen