Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Feral - Performance and Theatricality - 110

Hochgeladen von

Vanessa Delazeri MocellinOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Feral - Performance and Theatricality - 110

Hochgeladen von

Vanessa Delazeri MocellinCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

_ . " ."... .. r'l '~--,,..

-I

" llI III H I\I i\NI ')

"

i\N )I ' 1' 11 ' A l R JI ' i\' I I'\'

Rather than qucstion this c1assification and the insuffieient consideration it

g iws to men of the theatre like Craig or Appia , and to theatrical practices

<lS va ried as those 01' 1\ . Boal 's guerrilla Iheatre, B read & Puppet's political

Ihl'alrc, and the expe riments 0[' A. Bcnedetto. A. Mno uehki ne, the TN$, the

,"'all F rancisco Mime Troupe, and Mabo u Mi rH!s. r ~ hnlllJ likc lO make my

Il WIl IIse 01' il lo a ccoU lll ror Ih!! phcnonH!nn ll 01' rll.:rl'o mHHlee as it has

appeared in Ihe l Ini tcu Sta les anu F u ro pe O\ll'l I lll: pu sr IWCllly yeal's.

Inhunlud l'IllI l Nllll<l lisl pra cliccs in Ihc Iwenlies, as RoseLec Goldbcrg

has ~ h()wn in lu.!r hllOk, P f>r//'ll/(II/('('," artistic perf'ormance enjoyed quite a

h l) lll1l in the lifLil:s. especially in Ihe wake orlhe experiments ofAlJan Kapro\\'

amI ./llhn C age, Conceived as an art-l'orm at the juncture of other signi fy ing

practices as varied as dance, music, painting, architecture, and sClllpture,

Ill~rf'ormance seems paradoxically to correspond on all counts to the ne\\'

Ihcatre invoked by Artalld: a theatre 01' cruelty and violence, 01' the body

amI its drives, 01' displacement and " disruption ," 3 a non-nanative and non

n:prcsentational theatrc, 1 should like to analyse this experience of a ne\\'

genre in hopes of revealing its fundamental characteristics as weIJ as the process

hy \\'hich it works , My ultimate objective is to sho\\' what practices like these,

helonging to the limits of theatre, can tell us about theatricality and its

rclation to the actor and the stage.

Of the many characteristics of performance, 1 shall point to three that, thc

diversity 01' practices and modes notwithstanding, constitute the essential

f'oundations 01' all performance. They are flrst, the manipulation to which

perf'ormam;e subjects the performer's body - a fundamental and indispens

able elcment of any perJ'orming ac\; second , the manipulation of space , which

Ihe performer empties out and then carves up and inhabits in its tiniest nook s

and crannics: and finally , the relation that performance institutes between the

artist and the spectators, between the spectators and the work of art, and

between the work of art and the artist.

a) Firsl. the l1111nipulaliol1 (~r (he I}(xly. Performance is meant to be a physical

accomplishment , so the pcrform er works with his body the way a painter

does with his can vas. He explores it, manipulates it, paints it, covers it,

uncovers it, freezes it, moves it, cuts it, isolates it, and speaks to it as ifit were

a foreign object. It is a chameleon bod)' , a foreign body where the subject's

desires and repressions surface. This has been the experience of Hermann

Nitsch , Vito Acconci , and Elizabcth Chitty. Performance rejects all illusion,

in particular theatrical illusion originating in the rcpression of the body's

"haser" elements, and attempts instead to call attention to certain aspects of

the boJy - the face, gcstural mimicry, and the voice that would normally

escape notice. To this end, it turns to the various media telcphoto lenses, still

cameras , movie cameras, video screens. tclevision - which are there like so

many microscopes to magnify the infinitely small and focus the audience's attcn

tion on the limited physical spaces arbitrarily carved out by the performer's

desirc and transforllled into imaginary spaces, constituting a zonc where

his own emotional Aows and fantasics pass through. These physical spaces

can be parts of the pcrformer's own body magnified to infinity (bits of skin. a

hand , his hcad , etc.). but they can also be certain arbitrarily Iimited. natural

spaccs Ihat the pcrformer cho oses to wr a p t1p and thus reduce to the dimen

sion s o l'm un ipul a ble o bjecls (t.:r. ('hri sto's expe riments with this technique 4).

T hc boJ y is mallc conspicllollS: a body in picces, fragmcnted and yet one, a

booy r crCt.'iw d a nd renJercJ as I /IIa(( ' (I/dnr(' displaccmcl11, and fluctuation,

'o(,

' 11'1

77

PERFO RM AN C E A NO

THEATR I C ALfT Y

The subject dernystified

Josette Fral

Sourcc: Translaled by reTeSe Ly" ns, /vlodem Drama 25( 1) (1 <)~ 2) : 17 1 18 1,

Dcpending on one 's choice of experts, theatre today can be divided into two

different currcnts which 1 shall emphasize here by referring to a remark of

Annette Michelson 's on the performing arts that strikes me as particularly

relevant to my concern:

There are , in the contemporary renewal 01' performancc modes , t\Yo

basic and diverging impulses which shape and animate its major

innovations. The first , grounded in the idealist extensions of a Chris

tian past, is mythopoeic in its aspiration , ec1ectic in its forms, and

constantly traversed by the dominant and polymorphic style which

constitutes thc most tenacious vestige of tha t past: expressionism. Its

celebrants a re: fo r theater. Artaud. Grotowski , l'or film , Murnau and

Hrakhage. and for the dance, Wigman . Graham. The second . con

sistently secular in its commitment to objectificati on, proceeds from

Cubism and Constructivism ; its modcs are anal)'tic and its spokes

men are: for theater, Meyerhold and Brecht, for film , Eisenstein and

Snow , for dance. Cunningham and Rainer. 1

VISIi'"

!\rt I I\ NII 'I I ' \III "~' \NI.; '

1\1< '

I r " " I~'p l ~'~~" d ' lid 1I i.es lo free

cvcn al

the cost nI' greater violcnce. C onsider, tr cx alllp lc, 1h(! in lentionall y provllc

alive scenes where Acconci plays on stagc with his vari o lls bouily prouucts.

Such demonstrations, wh ich are brought to lhe surLlce mo re or lcss violently

by the performer, are presented to the Other' s view, to the view 01' other, in

order lhal lhey ma y undergo a collective veritication. O nce this exploration

of lhe body, and therefore of thc sllbject. has been complcted, anu once

cerlain repressions have been broughl lO light, objeetified, anu represenleu ,

they are frozen under the gaze of the spectalor, who appropriates them as a

for lll 01' knowledge. This leaves the performer free to go on t o new acts and

new performances.

For tbis reaso n, some: performances are unbearable; Ihose of Nitseh, for

exam ple, which do violence not only lO the performer (in bis case, a violence

freely consented to), but also to the spectator who is harassed by images that

both violate b im and do him violence. 5 The spectator has the feeling that he is

taking part in a ritual that combines all possiblc fransgressions - sexual and

physical , real and stageu ; a ritual bringing the performer back to lhe limits of

thc subjcCl conslituted as a whole; a ritual that, starting from the performer's

own "symbolic," attempts to explorc the hidden face of what makes him a

uniticd subjcct: in other words, the I'semiotic" or "chof(f" haun ting him. r, Vet

this is not a return to the divided and silent body of the mother, such as

Kristcva sees in Artalld, but inslead a march ahead towards the dissolution of

the subjecl, not in explosion, scattering, or madness - which are other ways 01'

re Lurning lo the origin - but in death. Performances as a phenomenon worked

through by the death drive: this comparison is not incidental. It is based on

an ex tensive, conscious practice, deliberately consented to: the experience

of a body \Vounded , dismembered , mutilated, and cut up (if only by a movie

camera: e l". Chitty's Demo Jvfode/), a body bel o nging lo a fully accepted

lesionism .'

The body is cut up not in order to negate ir. bul in order to bring it back to

Ji fe in each of its parts which have, each one, become an independent whole.

(T his process is idcntical to Buuel's in Un ehien andalou, when he has one of

the charaeters play wi th a severed hand on a bllsy road.) Instead of atrophy

ing, the bouy is therefore enriched by all the part-objects that make it up

ami whose richness the subject learns to discover in lhe eourse of the per

formance. These parl-objects are privileged, isolated, and magnified by the

performer as he studies their workings and mechanisms , and explores their

under-side, thereby presenting lhe spectators with an experience ;n vi/ro and

in slow motion of what usua 11y takes place on slage.

b) First the maniplll a tion ol' the body, lIJen he manipulo/ion o/ "'pace:

1he re i:; a rlll1~~tional identily between them thal Icads 1he re r rormer to pass

lh ro ugh Ihese places wi thollt cvcr m a kiJlg a dclini ti vc slll p. C a rvi ng out

imaginu ryor rea l spncc:; (;I ~ I\ ~o nci\ R,'d /'If/II'.\'). \ \111.' IIHll1wn l in nnc placc

alld lit!! lIexl lI111n a!nt ill Ihe o lhcr, lhe p ;rf) 11 111 1 IH'''tI ',l'lIles wilhill [hesc

a body Ihl' perfvJ'lllance L'OIH.:c ives

l ())\

" ' i 1(1

III! M \ N ( ", "N ') ' j'" Io!' II!

sil11l1ltan c() lI sl~

re ' \, "y

I'llysical a nu imaginary spaccs, bul insleau traverscs , ex

plo n:s. amI IJH' a~lIrcs thCIll , clTecling displacemenls and minute variations

within them . Hc uoes not occupy lhcm , nor do they limit him: he plays wilh

thc performance space as if it were an object and turns it into a machine

"acting upon thc sCllse organs." x Exactly like the body , therefore. space

becomes existential to the point 01' ceasing to exist as a setting and place. It no

longer sllrrounds and eneJoses the performance, but like the body , beeomes

part ofthe performance to such an exlent that it cannot be distinguished from

il. It is the performance. This phenomenon explains lhe idea that performance

can take place ol1ly within and for a sel spaee to which it is indissolubly tied .

Within this space, which becomes the site of an exploration of the subject,

the performer suddenly seems to be living in slow motion. Time strelches oul

nd dissolves as " swo11en, repetitive , exasperated" gestures (Luciano nga

Pin) seem to be killing time (el'. the almost lInbearablc slo\V motion of some 01'

Michael Snow's experimenls): gestures that are multiplied and begun again

and again (Id injinlum (cf. Acconei 's R ed Tapes), and that are always diffe r

ent , split in two by the camera recording and transmitting them as they are

being carried out on stage before our eyes (cL Chitty). This is Derrida's diffr

once made perceptible. From then on, there is neither past nor futllre, but

only a continuous present - that oflhe immediacy oft'hings, of an oc/ion wking

place. These gestures appear both as a finished prodllct and in the eourse 01'

being carried out , already completed and in motion (cL the use 01' cameras):

gestures that reveal their deepest workings and that the performer executes

only in order to discover what is hidden underneath them (this process is

comparable to Snow's camera filming its own tripod), And the performance

shows this gesture over and over to the point of saturating time, space, amI

the representalion with it sometimes to the point of nausea. Nothing is len

but a kinesics 01' gesture. Meaning - all meaning ~ has disappeareu.

Performance is the absence of meaning. This stalement can be easily

sllpported by anyone coming out of lhe thealre . (We need think only 01' the

audience's surprise and anger with the first "stagings" of the Living Theatre,

01' with those 01' Robert Wilson or Richard Foreman.) And yet, if any experi

cncc is meaningful , without a dOllbt it is that of performance. Performance

does not aim at a meaning, but rather makes meaning insofar as it works right

in those extremely blurred junctures out of which the subject eventllally

emcrges. And performance conscripts this subject both as a constituleu sub~

jlTI amI as a social sllbject in order to dislocate and demystify it.

Performa nce is the death of the subject. We just spoke of the death drive

as being inscribed in performance , conscioLIsly staged and brought into play

by a set of fredy intendcd anu accepted repetitions. This death drive, which

fra )! l11enls the hody and makcs il fun d ion likc so many pa rt-o bjects, reap

r cu rs at lite cll d nI" lhc pcr l"Orlll;IIHX wltcn il is fixcd 011 l he video screen.

Ind ccd, il is nI' inlc l'cl'l 1n II n 1l: Ih 111 ~vcry Iwrforrnance ultimatel y meelS

l il e vid,;\) scn:c 11, W\':I'C lite ~kI1l Y" l tll4' d '; lIhjl'l"l is frozcn and lIies. T hcre,

'11')

I S l' \,

1\ 11 I A N I j

" l llt I'f/l11\1\ N ( ' ,. i\ R I

perlrrmlJ ll:C (1111':0 a g a i ll em;ollll te ls n 'p rcsClIlll lII II I. 110111 which il wan tcul o

escape al all cos ls anu which lIlarks bol h ils fultilr lll'lIl alld il:; elld.

c) In point Oft~lct , the artisl's relati on to his own perfo rmance is no longer

one of an actor to his role, even if that role is his actua l one, as the Living

Theatre wanted it to be. When he refuses to be a protagonist, the performcr

no more plays himself than he represents himself. I nstead, he is a source of

production and displacement. Having become the point of passagc fo r energy

110ws gestural, vocal, libidinal, etc. - that traverse him without ever stand

ing still in a {lxed meaning or representation. he plays at putting those flows

to work and seizing networks. The gestures tl1at he carries out lead to nothing

if not to the flow of the desire that sets them in motion. T his respo nse proves

once again that a performa nce means nothing and aims for no single, specific

meaning, but attem pts instead to reveal places of passage, or, as Foreman

would say, "rhythm s" (the t rajectory of gesture. of the body, of the eamera,

ofview, etc.). In so doing, it attempts to wake the body - the performer's and

the speetator's- from the threatening anaesthesia haunting it.

It seems to me that all of us here are working on material, rearrang

ing it so that the resultant performance more accurately reflects not

a perception of the world - but the rhythms of an ideal world of

activity, remade, the better in which to do the kind of pereeption we

eaeh would like to be doing.

We are, lhen, presenting the audience with objects of a strange sort,

that can only be savored ifthe audience is prepared to establish ne\\'

perceptual habits - habits quite in conflict with the ones they have

been taught to apply at classical performance in order to be re~

warded with expeeted gratifieations. In classical performance, the

audience learns that if they allow attention to be led by a kind of

childish, regressive desire-for-sweets. the artist will ha ve strategically

placed those sweets at just the "crucial" points in the piece where

attention threatens to c1imax. 9

This technique accounts for the "sc\eetive inattention" that Richard Schechner

speaks ofin Essuys 0/1 Perjrl11u/1ce. 10 No more than the spectator, though, is

the performer implicated in the performance. He always keeps his viewi ng

rights. He is the eye, a substitute ror the carnera that is filming, freezi ng, o r

slowing down, and he causes slides, superpositions, and enlargements with a

space and on a body that have beco me the tools of his own exploration.

In our work , however. wha t's presented is n ot whal' s "appealing"

(th e min ute som clhing is a ppealin g it's l refe rence lu the past and lo

inhcrit cd "ta::;te") b ul ralher what h<l s hen:lolOl c uo l heclI orga n

ized by lhe mi no inlo I"Ixogniza blc .Uc :; l n l l '\ ~ ,'V\"I yllrlll! Ihal has

10

l ' Ji ItI ( 1ft M ;\ N ('le

N "

I 11 I \ I IU

l 1\

n y

hL' rel\)J'llIC "c~ caped Ilolice." And the ternptation cach of us fights, I

I hink. is lo becol1le prematurely "intcrested" in what we uncover. 11

This situation is all the more difficult ror the spectator since performance,

caught up as it is in an unending series of often very minor transformations,

escapes formalismo Having no set form, every performance constitutes its

IIwn genrc, and every artist brings to it, according to hi s background and

dcsires, subtly different shadings that are hs alone: T risha Brown 's per

t"ormances lean towards the dance, Meredith M onk 's towards music Some,

however, tend in spite of themsclves towards theatre: Acconci's Red Tapes,

f"or example, or Michael Smith 's Dow/1 i/1 lhe Rec Room. AH 01' this goes to

show that it is hard to talk about performance. This difficulty can be seen also

in Ihe various kinds of research on the subjeet. often in the forms of photo

alhums recording the fixed traces ofperformances that are forever over, with

I he few critical studies 01' tibe subject tending towards historicism or descrip

lion. Here we touch upon a problem identical to one presented by the thcatre

IIf non-represcntation: how can we talk about the subject without betraying

il? 110\V can we explain it? From descriptions of stagings taking place else

where or existing no longer. to the fragmente\l'y, critical discourse of scholars,

I he theatrical experience is bound al\Vays to escape any attempt to give an

accurate account of it. Faced with this problem. which is fundamental to a1l

spectacles, performance has given selfits own memory. With the help oft he

video camera with which every performance ends , it has provided itself with

a past.

* *

"k

Ir one judges from everything that has thus far been said about performance,

il certainly seems difficult to ascertain the relationship between theatre and

performance. And if \Ve turn to the statements of certain performers, that

n:lationship would even seem to be, of necessity , one of exclusion. Michac\

l :ried \vrites to that effect: "theatre and theatricality are at war today, not

sil11ply with modernist painting (or modernist painting and sculpture). but

with art as such - and to the extent that different arts can be described as

IlIodernist. with modernist sensibility as such."'2 F ried sets forth his argu

IIlcn! in two parts:

1) 'hc Sl/ceC,I's. CI'C/1 lhe surl'il'u/.

01' he arls has come i/1creasi/1g/y

lo dcpend

U/1 lh('ir (/hifily lo de/CUI lhealre.

') /l rr c!('g('I/NurC.l

(/.1'

ir (/jljl rl!(.J{' h(,I' rhe ("()l1ditiol7 ol'rhcalrc."

II (\\v " s lll"h:, sla lc.: ll1cn l lo he ....:\plllimd lel :jOllc j usti ried? If wc agrce wit h

1lI-llld: Ihal Ih ca ln,':l,;illI lI lIl c'{r: tp ~' I"\ tll ' ~'r I Csc n l:rli \ln wh ich ~ic Il a lcs and

II

VIS II /\I .

\ I( I

ANL. l'I!H! rllltM,\N I.' 1

\I( ..

1IlH.ll' rJlIilll:S il, ami if we a lso ill:! llT I ha 1 1" l'Ull l' ~'tlIIIIOI ~'''ca pc lIarrativity (all

the current theatrical cxpc ricllccs rm vc as IlIlH.: h , I:X(,:C pl pcrhaps ror those 01'

Wilson and Fo reman, which alrcady bclong to performance), thcn it \Vould

seem obvious that theatrc and art are incQmpatible. "In the thcatre, every

form once boro is mortal ... ," Peter Brook writes in The Empty Space. 14 But

as I havejust stated , performance is not a formalism. It rejects form, which is

immobility, and opts, instead, fol' discontinuity and slippagc. Jt seeks what

Kaprow was already calling for in happenings thirty years ago: "The dividing

line between art and lite should remain as fluid and indistinct as possible and

time and space should remain variable and discontinuollS so that, by continu

ing to be open phenomena capable ofgiving way to change and the unexpected,

performances take placc only once.'' .I Are \Ve very far from what Artaud

advocateo for the theatre , or from what the Living Theatre ano Groto\Vski ,

following Artauo , have demanoeo as the mooel for theatre 's rellewal: Ihe

stage as a " li ving" place ano the playas a "one time only" experience?

That performance shoulo reject its oepe.noence on thea tre is certainly a sign

that it is not only possible, but without a oOllbt also legimate, to compare

theatre ano performance, since no one ever insists upon his oistance from

something unless he is afraio 01' resembling it. I shall not attempt, therefore,

to point out the similarities between theatre and performance, but rather

show how the two mooes camplement each other ano stress what theatre can

learo from performance. Inoeeo , in its very strippeo-oown workings , its

exploration of the booy. ano its joining 01' time ano space, performance gives

us a kind of theatricality in slow motion: the kino \Ve find at work in tooay's

theatre. Performance explores the unoer-sioe of that theatre, giving the audi

ence a glimpse of its insioe, its reverse sioe, its hiooen face.

Like performance, theatre oeals with the imaginary (in the Lacanian sense

of the term). [n other woros , it makes use 01' a technique 01' constructing

space, allowing subjects to settle there: first the canstruction of physical space,

ano then of psychological space. A strange paralle1, mooel1ing the shape of

stage space on the subject's space ano vice versa , can be traceo bet ween them .

Th US , whenever an actor is expecteo to ingest the parts he plays so as to

bccome one \Vith them (here \Ve might think ofnineteenth-century theatre, of

natllralist theatre, ano of Sarah Bernharot's first parts) , the stage asserts its

nneness ano its tota1ity . It is, ano it is Ol1e, ano the actor, as l unitary subjcct,

hclongs to its wholeness.

l' U < I I I I( M \ N ( : t

!\ N , ,

I 11 1, \ I IU ( , \ 1.1 I Y

Closer to us, in experiences of present-day theatre (experimental theatre.

alkrnativc theatre

here \Ve might think 01' the Living Theatre 's first ex

perirnents, or, more recently, 01' Bob Wilson's), the \Vay theatrical space is

cnnstructed attcmpts to ma ke ta ngibl e a mI appa rent the \Vh o lc play 01' the

imagin a ry as it seLs subjects (and nOl CI slIbjcCl) (lB Slilgc. T hc proCCsscs

whc rc hy Ihe Ih ca tril:a l r hcn olllcnon is w ns lrllCl c\ 1 as \Vc ll ;IS lhe f'olln J a li on

Ill'l h1I ph Cl1 mnCIlO II a n I.!xtcnsivc play (1 rd oU hllOf IlId pc,,'rf1l lllal ion lha t is

I1h U\,.' 01 Icss .,hv iolls <1m.! llJ \l rl: 0 1' Icss dllk ll'II f1 i1l n l dl' Pl'lldil l!' II p O Il IIIc!

specilic d irt:cll1l a mi aillls lhlls beco me ap parent : the oivision bctwcen actor

amI characlcr (a slIhjcct that Pirandello dealt with very well) ; the oOllbling 01'

the actor (insofar as he survives arter lhe oeath of the text) ano the character;

the ooubling of the author ano the oirector (cf. Ariane Mnouchkine); amI

lastly, the ooubling of the oirector ano thc actor (cL Schcchncr in e/o/hes).

As a group, these permlltations forl11 oifferent projcction spaces, reprcsenting

different positions of oesire by sctting oown subjects in process.

Subjects in process: the sllbject constructeo on stagc projects himself into

objects (charactcrs in cla ssical thcatre , part-objects in performance) \vhich he

can invent , multiply , ano eliminate if neco be . Ano these constructeo objects,

proollcts of his ima.gination ano 01' its oifferent positions of oesire, constitute

so many "a"-objeets for him to usc or abuse accoroing to the neeos of his

inner economy (as with the use of movie cameras or vioeo screens in ma ny

performances). In the theatre , these "a"-o bjccts are fro zen for the ouration of

the pl ay, In performance, on the other hano , they move about ano reveal an

imaginary that has not been a1ienateo in a fi g ure 01' fixation like characters in

the classical theatre, or in any other fixeo theatrical formo rol' it is inoeeo a

q uestion of the " subject," ano not of characters. in today's theatre (Foreman ,

Wilson) and in performance . 01' course, the conventional basis of the actor's

"art," inspireo by Stanislavski , requires the actor to live his character from

within ano canceal the ouplicity that inhabits him while he is on stage. Brecht

rose up against this i11usion when he calleo for a oistancing of the actor from

his part ano a oistancing of the spectator from the stage. When he is faceo

\Vith this prob[em , the performer's response is original, since it seems to

resol ve the oilemma by completely renouncin g character ano putting the

artist himse1f on stage . The artist takes the position 01' a oesiring - a perform

ing - subject , but is nonetheless an anonymous subject playing the part of

himsclf on sta ge. From then on, since it tells of nothing ano imitates no one,

pcrformance escapes all illusion ano represe nta tion. With neither past nor

fllture , performance /ak e.l' place. It turos th e stage into an event from which

the subject will emerge transformeo until a nother performance, whcn it can

continuc on its \Va y. As lon g as performance rej ects narrativity ano repre

scntation in th is way, it also rejects the symbolic organization oominating

theatrc ano exposes the conoition s of theatricality as they are. Theatrica1ity

is maoe of this enoless play ano 01' these continuolls oisplacements of the

position of desire , in other words, 01' the position 01' the subject in process

within an imaginary eonstructive space.

[t is prccisely when it comes to the position ofthe subject, that performance

;lI1d thcatrc \Vollld seem to be mutllally exclusive ano that thcatre \Voulo per

h l;lp~ havc sOl1lcthing to learn fro m performance. Inoeeo , theatre cannot do

wilho ll llhc su b jcct (a co mpktdy tlss urm:d subject) , ano the exercises lo which

Mcycrhrlld '.Ind , la ter on , <.irotowsk i slIbjcctcd thcir stuoents cOlllo only

(.'o ll solidu lc 1he pllsil io n ()I' 1111' IIl1i llll V sllhjl.'cl 0 11 sla ge . Performance, how

L've r, all hll Llph bc~j lllli llg will! 11 11l'11 l'l' IIV ; 1~;t; lIl l1l'O su bjcCl, bri ngs clllu tional

212

' 1I

V I S I \ 1

\ It I

"N 1I l' 11 It l' ti H M1\

1'( , ln IIlt M A N ( , I

Il ows a nd ~y lllholil' ohjl.'ds illl!' a lk sldlll l/l: d ,p llI ' IIlc hody , sp:i\X inl0 <In

infrasymbolic lOnc . Thesc obj;cl:s a r; o nl y il ll.: id cl1 la ll y cOllvcycJ by a sl/hj('CI

(herc, thc pcrl'ormcr), anJ that subjccL Icnds hilllsdf ollly vcry superlicia lly

ami partiaH y to his own performance. Brokon d o wn into sCl1liotic bundlcs

and drivcs, he is a purc catalyst. He is what p ermils the appearance 01' whal

shou/d appear. Indeed, he makes tran sition , movement, a nd d isplaccment

possiblc.

Performance, therefore, appears as a primary process lacking tc1eology

and unaccompanied by any secondary process , since performance has noth

ing to represent for anyone. As a result, performance indicates the theatre \

nwrgin (Schechner wo uld say its "seal1l"), theatre's fringes, something which

is never said, but which, although hidden , is necessarily prcsent. Perform

ance demystifies the subject on stage: the subject's being is simultaneously

exp/oded into part-objects and cundel1.1'ed in each 01' those objects, which have

themselves become independent entities, each being simultaneously a mar

gin and a centre. Margin does not refer here to that which is excluded. On

the contrary, it is used in the Derridian sense of the term to mean the trame,

and consequently, what in the subje;t is most important, most hidden , most

reprcssed , yet most active as well (Derrida would say the "Parergon "1 6).

In other words, it refers to the subject's entirc store of non-theatrieality.

Performances can be seen , thcrefore, as a storehouse for the accessories of

the symbolic, a depository of signifiers which are all outside of established

discourse and behind the scenes 01' theatricality. The theatre cannot callupon

them as such, but, by il1lplication , it is upon these accessories that theatre is

built.

In contrast to performance, theatre cannot keep from setting up, stating,

constructing, ami giving points of view: the director's point 01' view, the

author's towards the action, the actor's towards the stage, the spectator's

towards the actor. There is a multiplicity 01' viewpoints and gazes, a "densi ty

of signs" (to quote Barthes l7) setting up a thetic multiplicity absent from

performance.

Theatricality can therefore be seen as composed 01' t\Vo different parts: o ue

highlights performance ami is made up of the rea/ilies ollhe il11aginary; and

the other highlights the theatrical and is made up 01' speciJic .Iyrnho/ic slru c

lUres. The former origina tes within the subject and allows his flows of desire

to speak; the latter inscribes the subject in thelaw ami in theatrical codes,

which is to say , in lhe symbolic. Theatricality arises from lhe play between

these two realities . From then on it is necessarily a theatricality tied to a

desiring subject, a fact which no doubt accounts for our difficulty in dcfin ing

i1. Theatrica lity cannot he, it must befr someone_ In other words, it is fr

lhe Olher.

Th c Ill llltiplicily nI' silllultaneous struc lu reli lha( CHn

secn al work in

pe rformance scems, in facl, 10 cons lilu ll! In ut 11 n rles!'> , aC l!)J'!cSli, and

d irl!c lorll:ss illli'o !I! ('(// U ('(/!ill '. Ind cl!d , pcrfnfm;lllt,;\ '1\'\: 11 '" lit be ultcm pti i! lo

ne

Id

J\ N I I

1" I f\ I I(

(1'

,\1 I .. \'

Il'vca l lid tu sl : I)' ~ sOllll'lhin g tha l l(J\)k pl: l\':c hdrl' the rcprescntation orthe

slIhjcl'l (l~ W II ir il L10es so by lIs ing;lll aln:ady CIlnslilllted su~iect) , in the salTle

wa y thal il is intcrcsted more in (In actoion as it is being produced than in a

lin ishcd product. Now, what takes place on stage comprises f1ows, accumula

tiollS , anJ conneetions ofsignifiers that ha ve been organized neither in acode

(hl~ncc the multiplicity 01' media ami signifying languages that performance

IIlakes use 01': bils 01' representation ami narration and bits of meaning), nor

in strllctures permitting signification. Performance can therefore be seen as a

nlachinc working with serial signifiers: pieces of bodies (d. the dismcmber

lIlent and Icsionism we have already discLlssed), as \Vell as pieces 01' meaning,

rcpresentation , and libidinal f1O\vs , bits of objects joined together in m uJtipolar

l'IlIlcatenations (cf. Acconci 's Red Tapes and the fragmentary spaces he moves

ahout in: bits ofa building, bits ofrooms , bits ofwalls, etc.). i\nd all ofthis is

without narrativity .

The absence 01' narrativity (continuoLls narrativity, that is) is one of lhe

dominant characteristics 01' performance. 11' the performer should unwittingly

1'.ive in to the temptation of narrativity, he does so never continuously or

l'onsistently, but rather ironically with a certain rcmove , as if he were quot

ing, or in order to reveal its inner workings . This absence lcads to a certain

rrustration on the part 01' the spectator, when he is confronted with perform

ance which takes him away from the experience oftheatrieality. F or there is

lIothing to say about performance, nothing to tell yourself. nothing to gr<lsp,

projcct, introject, except for fto ws, networks, and systems. Everything a ppca rs

anJ disappears like a galaxy of "transitional objects"l~ representing o nly the

failures 01' representation . To experience performance, one must simultane

lIusly be there and take part in it , while ;ontinuing to be an outsider. Perform

:mce not only speaks to the mind , but also spcaks to the sen ses (cf. Angcla

Ricci Lucchi 's and Gianikian 's experiments with smell), ami it speaks from

subject to subject. It attempts not to teH (like theatre), but rather to provokc

synaesthetic relationships between subjects. In this, it is similar to Wilson 's

nI(' L/le and Times o/ JO.l'eph Stalin as described by Schechner in Essay s on

l'crjrnwl1ce. 19

Performance can therefore be seen as an art-form whose primary aim is to

lindo "competencies" (which are primarily theatrical). Performance readjusts

I hcse competcncies and redistributes them in a desystemati7.ed arrange

menL We cannot avoid speaking of "deconstruction" here. We are not , how

('vcr, dealing with a "Iinguistico-theoretical" gesture, but rather with a real

gesturc, a kind of deterritorialized gesturality. As such, performance poses a

challenge lo the theatre and to any refiection that theatre might make upon

ilsdr. Performance rorients such rcllcctions by forcing them to open up and

by compc lling lhelll lO expl o re Ihe Illargins 01' theatre. For this reason, an

I,lxc llrsioll inll) performance has sccnll:d 11\)1 onl y interesting, but essential to

IIltill lHh.' Cl)lh.;crn , which is lO Jllllll! h;k 1\l lhe Lhl:atre arter l long det o ur

hc hilld the SCCI1 CS uf lhca l1 i ~: di l y

,,"r

'l

\ . I t, 11

t\

1(

t\ N

1)

l' 1: JI I H

li

1\ 1 1\ ~ 1.- 1:

/1 I( I

N I,h"

A lIlI ll tll.: Mi chdsOll , " Yvollnc I{:lim:r. 1'01 1 (l IH' 1111' 1);lIIl'llr :111(1 Ih u 1):lIIl'C,"

Ir(jimllll , 12 (Janua ry 1(>74),57 .

2 RoseLee GolJbcrg, Pcr/im1/ancc: Lil'c Art, IVOY lo 1/1(' Prc.\"('/Il (N(~ w Yo rk , Il)7(.

3 Lueiano Inga- Pill ~ ay s this in his prefacc to the pho to album on pc rforl11i:1l1cu.

Per/mnan(:e.l', J-Japfienings, AC/ion.\', Erenl.\', Aclil'ilies. Jllslallaliolls (Padua, 1970).

4 By wrapping up diffs and entire buddings in their natural sunroundings, Christo

isolates them. He thus sirnultaneously ernphasizes their gigantie s2e and negates it

by his ve ry project, and estra nges his objects from the natural setting frol11 which

he takes them (cf. Photo 11 0 . 48 in the illustrations to Inga-Pin).

5 The performances ofthe Austrian artist Hermann Nitsch were inspired by aneient

Diollysiac ami C hrist ia n rites adapted to a modern eontext designed to illustrate in

l praetical fi:lshion thc Aristotelian notion of eatharsis through fear, terror, 01'

cornpassion. Ilis Orgies. Mys leries, Thealre were performed on nurnerous occa

sions in the scventies. A typieal performance l1sted several hours. 1t began with

loud rnusie followed by Nitseh ordering the cerelllonies to begin. A l1mb with its

throat slit was brought into the midst ofthe participants. Its earcass was crueified ,

and its intestines removed an d po ured (with their blood) over a naked rnan or

woman lying beneath the animal. This praetice originated in Nitseh ' s belief th a t

humanity 's aggressive instincts had been repressed by the media. Even ritual

animal saerifiees , which were so eommon alllong primitive pcoples, have tot a lly

disappeared frolll modern experience. Nitsch's ritual acts thus represented a way

of giving full rein to the repressed ene rgy in mano At the same time, they func

tioned as aets of purification and redemption through suffering. (Ths description

is based on Ihe diseussi on found in Goldberg, p. 106.)

6 These notions are borrowed fr om Juli a Kristeva, La R vol/ltion da !angage p otique

(Paris, 1974).

7 " Lesionism " refers to a practiee whereby the bod y is represented no! as an entity

or a unitcd wh ole, but as d iv idcd into P,HtS o r fragments (cL Inga-Pin , p. 5).

8 lnga-Pin , p. 2.

9 Stephcn Koeh , Rich a rd Foreman , et al. , " Pelformance. A Conversation ," Arlfrum,

,1 \ (Deeember 1972), 53 - 54.

10 Richard Schechner, El-says on Perjrr/'la/'lce Theo ry. 1970 /976 (New York, 1977),

p.147.

11 Koch ,54.

12 Michael Fried , " Art and Objecthood ," Arlfrwn (Junc 1(67), rpt. in Minima! Arl.

ed. Gregory Battcock (New York , 1(68), p. 139.

13 Ibid. , pp. 139 141.

14 Peter Brook , Tll e Emply ,'>'p({ce (Ncw York , 1(69), p. 16.

15 Allan Ka p row , A.\'semhlage. Enl'iro/lmenlS a/'le! Happenings (New Yo rk, 1(66),

p. 190, quoted in Pnjrmnallce hy Arr\'IS , ed. A. A . Bronso n and Peggy Galc

(Toronto, 1(79), p. 193.

16 See Jaeques Derrida, La Vril 1'11 peil1lure (Paris, 1978).

17 Ro land Barthes, "Baudelai,re 's Theater," in Critical Essays, transo Richard Iloward

(Evanston , 1972), p. 26.

18 See Donald W. Winnieott. P!ayil1g (//1(1 R ('a lily (New York, 1971).

19 Schechner develops the idea 01' "selective inattenti on" in his discu ssio n 01' Wilson ' s

Tlle Lije a{u! Times of.fosepll Sla!in (Schechner. pp. 147 - 148):

I' P I( I ' ! lItl\l l\N f '

Wt; 111 11111 IIlIlv dmill !!

n1:1 uy

111,'

hi~

i\N I '

I I I I!.' I llI C i\I . ' 1 )

1~ 1IIIIIIIIl' IlIll' I I I II~~ I(lIIS hU I :liso durillg

01 Ilt l' ~I c ls nI' Wilsll ll ' s St:VCII-iI(:I IIp,:ra , 1'I1l: opera uc;rru l at 7 pm

alld 1':1 11 m uru l!tan 12 hOllrs . . .. '1 11<.: bchilvior in the I.e Perq spacc was

lIot Ihc same throughout Ihe lIi gh1. I)uring the lirst three <Lets the space

was generally cm p ty exept for inte rmi ssio n , But increasi ng ly as the

night went Oll pco plc cam e to the space anu stayed th e re speak ing to

fricnds, taking a break {'rom the performance , to loop o ut o fth e ope ra ,

later to re-cnter. About halfthe audience left th e IIAM before th e perform

ance was ove..; but those who remained , like repea ted siftings of flour ,

were finer and fin er cxamples of Wi1son fans: the a lldienee sorted itself

out until those of liS who sta yed for th e wholc ope ra sha red not only the

expericl1ce 01' Wilson ' s work but the expcrience of expe ri encing iL

For (he DeccmbeL 1973, performances ... al I h ~ Broo kly n Academ y 01'

M lIsie's " pe rll ho use . the Le Pe rq space f'\) \l lll 111' ahnlll 150 leel hy 80

-ceI W;IS ~ e t up wilh la blcs, c ha irs, n: rr~ IIIIH'lI t ~ a " llw wller.: pcoplc

11 (,

1I "

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Sejarah IndiaDokument7 SeitenSejarah IndiaNabiha solehahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dragon Soul AlchemyDokument17 SeitenDragon Soul AlchemyMarkus SchimpfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cpar ReviewerDokument4 SeitenCpar ReviewerJelaineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Setting Stones in Metal ClayDokument21 SeitenSetting Stones in Metal ClayJoyasLoni100% (1)

- Answer Key To Unit 2 QuizDokument2 SeitenAnswer Key To Unit 2 QuizCarlos Alberto de MendonçaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Styles of Art (Part 1)Dokument6 SeitenStyles of Art (Part 1)SEAN ANDREX MARTINEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peace and Prosperity: West TambaramDokument9 SeitenPeace and Prosperity: West TambaramthenambikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marc Chagall, (Born July 7, 1887Dokument8 SeitenMarc Chagall, (Born July 7, 1887David BriceñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Engineering: Selective Ceramic Processing in The Middle Balsas Region of Guerrero, Mexico.Dokument370 SeitenAncient Engineering: Selective Ceramic Processing in The Middle Balsas Region of Guerrero, Mexico.Citlalii BaronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notre Dame de ParisDokument14 SeitenNotre Dame de ParisKaushik JayaveeranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Estimate Construction of London PalaceDokument6 SeitenEstimate Construction of London PalaceRajwinder Singh BansalNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Greek Cave Sanctuary in Sphakia SW CreteDokument54 SeitenA Greek Cave Sanctuary in Sphakia SW CreteJeronimo BareaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boq Sipil Gi 150 KV Rufey - KontraktorDokument63 SeitenBoq Sipil Gi 150 KV Rufey - KontraktorTaufik RaharjoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art of ExaggerationDokument32 SeitenArt of Exaggerationkaem123100% (1)

- Blue Mirror How ToDokument8 SeitenBlue Mirror How TopulidofernandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buah BuahanDokument10 SeitenBuah BuahanMawar JinggaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Greek ArchitectureDokument38 SeitenAncient Greek Architectureahmedseid770Noch keine Bewertungen

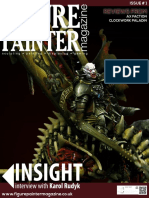

- Reviews From: WWW - Figurepaintermagazine.co - UkDokument56 SeitenReviews From: WWW - Figurepaintermagazine.co - UkMark SoleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative StudyDokument18 SeitenComparative StudyAlma KerkettaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Naram-Sin of AkkadDokument4 SeitenNaram-Sin of AkkadValentin MateiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeanfrancois Chevrier The Adventures of The Picture Form in The History of Photography 1Dokument22 SeitenJeanfrancois Chevrier The Adventures of The Picture Form in The History of Photography 1Carlos Henrique SiqueiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art App L6Dokument6 SeitenArt App L6beavalencia20Noch keine Bewertungen

- (This Paper Consists of 6 Pages) Time Allowed: 60 Minutes: A. Believed B. Prepared C. InvolvedDokument5 Seiten(This Paper Consists of 6 Pages) Time Allowed: 60 Minutes: A. Believed B. Prepared C. InvolvedNguyễn Việt QuânNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mapeh 7 Week 6Dokument2 SeitenMapeh 7 Week 6Edmar MejiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nosnje EngDokument64 SeitenNosnje EngCile MiticNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cloud Factory: Shaun Belcher Excerpt FromDokument21 SeitenThe Cloud Factory: Shaun Belcher Excerpt FromShaun BelcherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gouache Acrylic Painting TechniquesDokument3 SeitenGouache Acrylic Painting TechniquesCraig0% (1)

- Fowlers of Two Revolutionary War PatriotsDokument3 SeitenFowlers of Two Revolutionary War PatriotsHerman KarlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black and White (And A Bit in Between) by Celerie Kemble - ExcerptDokument22 SeitenBlack and White (And A Bit in Between) by Celerie Kemble - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group0% (2)

- Bauhaus ScandinavianDokument18 SeitenBauhaus ScandinavianRaquel De LeonNoch keine Bewertungen