Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1 s2.0 S0897189715002074 Main

Hochgeladen von

KhairulOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1 s2.0 S0897189715002074 Main

Hochgeladen von

KhairulCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Applied Nursing Research 30 (2016) 9497

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Applied Nursing Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apnr

The inuence of high delity simulation on rst responders retention of

CPR knowledge

Ruth Everett-Thomas, RN, PhD a,, Vernice Turnbull-Horton, RN, MSN b, Beatriz Valdes, RN, MSN c,

Guillermo R. Valdes, RN, DNP d, Lisa F. Rosen, MA a, David J. Birnbach, MD, MPH e

a

University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, UM-JMH Center for Patient Safety R-370A, Miami, Florida 33136

Ambulatory Services Division, Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, Florida 33136

University Of Miami, M. Christine Schwartz School of Nursing and Health Studies, Coral Gables, FL 33146

d

Miami Dade College: Benjamin Leon School of Nursing, Miami Florida, 33132

e

University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, UM-JMH Center for Patient Safety, Coral Gables FL, 33146

b

c

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 24 June 2015

Revised 6 November 2015

Accepted 8 November 2015

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

High delity simulation

Knowledge

Retention

Training

a b s t r a c t

Introduction: The purpose of this study was to identify the impact of high-delity simulation on the retention of

basic life support cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) knowledge among a group of healthcare providers (HCPs).

Methods: A twenty-ve question exam was completed by nurses and nurse technicians over a two-year period

before and after mandatory CPR training with high-delity simulation.

Results: Most HCPs scored near 50% or below the passing score (80%) with a mean range of scores between 28% and

84%. HCPs missed questions on the exam that requested specic details related to technique or human physiology

during CPR.

Conclusion: The current teaching method for basic life support may be enhanced by using high-delity simulation,

but this modality alone is not enough to support HCPs retention of CPR knowledge. Additional studies are needed

to identify strategies that will help HCPs remember specic and detailed information in the CPR algorithm.

2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

2. Background

During a sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) or heart attack every second

counts. As brain and organ injury increases the chance of survival

decreases (American Heart Association, 2013). Cardiac arrest occurs in

individuals of all ages. Basic life support (BLS) measures are performed

to manually pump the heart and circulate oxygenated blood to vital

organs (American Heart Association, 2013). Unfortunately, the body

may suffer irreversible organ damage after four to seven minutes once

blood ow has stopped and oxygen cannot be transported to the heart

or brain (Niles et al., 2011).This simple cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(CPR) method has proven to be effective when performed correctly by

healthcare providers (HCPs) (American Heart Association, 2013).

The rst ve minutes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

performance is crucial for optimal survival of a heart attack. There is a

direct link between knowledge, actual performance of CPR measures

and poor survival outcomes (American Heart Association, 2013

Updates). Therefore, we evaluated healthcare providers (nurses and

nurse assistants) knowledge after mandatory CPR training to determine

the amount of retention at ve time intervals.

In the US, guidelines for CPR are updated every ve years to include

ongoing research ndings. While researchers agree the technical

aspects of CPR may be simple nonetheless performing them correctly

has proven difcult (Al Hadid & Suleiman, 2012). Chee (2014) suggests

that the retention of CPR skills is closely associated with the instructor,

learner, curriculum, and frequency of timing in which the training takes

place (deliberate practice). Experts in simulation concur with these

ndings and propose that simulated environments may be the future

modality for acquiring and maintaining skills (Issenberg & Scalese,

2007). According to Chee (2014), deliberate practice is one of the best

teaching strategies for adult students to learn and retain information.

This learner-centered experience is embedded in an appropriate clinical

context allowing for deliberate practice after a period of reection

(Chee, 2014; Issenberg & Scalese, 2007). Simulation is unlike traditional

lectures and other formats in which the learner is a passive observer.

Researchers conclude that healthcare simulation is gaining widespread

acceptance as a teaching modality which can be used to enhance any

existing education curriculum (Chee, 2014; Issenberg & Scalese, 2007).

Additionally, high-delity simulation (HFS) including sophisticated

mannequins, updated computer software, high-tech medical equipment

and highly-trained personnel creates a more realistic environment helping

users suspend disbelief (Aqel & Ahmad, 2014; Tawalbeh & Tubaishat, 2013).

Corresponding author.

E-mail address: reverett@med.miami.edu (R. Everett-Thomas).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2015.11.005

0897-1897/ 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

R. Everett-Thomas et al. / Applied Nursing Research 30 (2016) 9497

2.1. High-delity simulation

Using HFS, instructors can control the mannequins life-like responses

by making various adjustments to the scenario depending upon the

students interventions. An interaction between the mannequin, student

and instructor enhances experiential learning. Students are given time

to practice various skills while allowing the instructor to evaluate their

clinical decision-making and critical thinking skills (Nevin, Neill, &

Mulkerrins, 2014). Although CPR recertication skills are still performed

using low-delity or static mannequins (resusci-Anne), many healthcare organizations are beginning to incorporate HFS into their annual

mandatory training courses (Ackermann, 2009; Tawalbeh & Tubaishat,

2013). Despite the signicant data regarding the degradation of CPR

knowledge and skills after standard recertication, limited research mentions a decrease in knowledge after HFS training (Adekola, Menkiti, &

Desalu, 2013; Aqel & Ahmad, 2014; Sankar, Vijayakanthi, Sankar, &

Dubey, 2013). Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate healthcare

practioners CPR knowledge and determine the effect of HFS on retention

after mandatory BLS-CPR training.

95

the rate and depth of compressions, number of rescue breaths, and the

amount of time required to take a pulse along with its location. Two

questions were identical and repeated; however, the multiple choice

answers were placed in a different sequence.

The results of the written exam were not reviewed with the staff and

were used as a quality measure for the clinic educators to improve their

training program. At the end of the data collection period, additional

information about CPR was provided to the staff along with pocket

cards, instructional posters in the clinic area, and the AHA 2010 BLS

Quick Reference Guide.

3.3. Data analysis

All data were analyzed using frequency distributions, ANOVA and

the student t-test with the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) version 21, and a 0.05 probability level was used to determine

a statistical difference between the groups.

4. Results

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and setting

A convenience sample of HCPs (registered nurses, licensed practical

nurses, nursing assistants and patient care technicians) from ve specialty

outpatient clinics was included in this study. They were previously

recertied in BLS-CPR skills using the 2010 AHA updated guidelines. As

part of the organizations mandatory BLS training program, all HCPs

were required to participate in at least one mock-code prior to recertication. Over a two year period (7/2011 to 8/2013) HCPs from the outpatient

clinic underwent mandatory CPR training (i.e. mock cardiopulmonary

arrest code) using high-delity simulators in the hospitals simulation

center. Also, one group of participants took the exam nearly two years

later. This test occurred prior to their AHA recertication, and they received only one training session with HFS. All sessions were faculty-led

and videotaped to guide the debrieng process immediately after each

encounter. HCPs participated as small groups in one mandatory session

of two mock code scenarios to enhance training.

3.2. Procedures

One group of HCPs was given the written examination prior to their

annual mandatory training, and all other participants were given the

test after the training period. This study was approved by the Institution

Review Board. A registered nurse obtained informed consent and distributed a 25-question written CPR exam to all HCPs. HCPs volunteered

depending upon their availability to take the test during and/ or

immediately after clinic hours. Information about CPR was not reviewed

prior to taking the test, and no instructional CPR posters were noted in

the clinic area. Individuals were provided 30 to 45 min of uninterrupted

quiet time in a private ofce and were monitored throughout the testing

period. The test was given at ve different time intervals (baseline, b3 months, b 6 months, b 9 months, and at two years after HFS mockcode training but prior to recertication). No identifying or demographic

information was collected on the test. This course of action provided the

HCPs with anonymity and a level of assurance their scores would not be

used either favorably or unfavorably within the organization. Also, all

individuals could only take the test once regardless of the time when

they completed their mandatory training.

The 25-question exam was derived from the AHA 2010 guidelines

for BLS-CPR and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) recertication;

however, questions about child and infant CPR were excluded. The

exam questions focused on both one and two rescuer performance of

adult BLS-CPR skills and the correct use of an AED device. Five questions

replaced those related to infant and child. These questions addressed

Of the 57 individuals that took the written exam, only two received

passing scores N80%. Five percent of the group members scored (72%)

below the passing score. The range of percent scores for all of the tests

was between 28% and 84%. For each time interval including the baseline,

the mean percent scores were near or below 50%. Total mean scores for

all exams in the b3 month interval were 54%, slightly higher than all

other mean scores. Individuals that took the exam prior to simulation

training and during the b9 month interval after the simulation training

had the lowest total mean percent scores (43% and 44%). There were no

signicant differences between any of the total mean percent scores for

all time intervals (Table 1).

Most HCPs missed 12 of the 25 questions (48%) on the written

exam, and only two answered seven questions correctly (28%). Also,

95% (54/57) of the individuals who took the exam answered the AED

questions incorrectly. A few HCPs remembered the number of seconds

recommended to give a breath in the presence of an advanced airway.

Approximately 80% (45/57) missed both questions about the correct

use of the bag valve-mask (BVM) device for both one and two rescuers.

Nearly 85% (48/57) of the HCPs incorrectly answered the physiology

question related to the reason for performing chest compressions.

Sixty percent (34/57) of this cohort incorrectly answered all three

questions regarding hand placement, depth and rate of compressions.

Two identical questions related to the specic rate and depth of

compressions were repeated. The order of the multiple choice answers

were rearranged, and 50% (29/57) of the HCPs missed all four questions.

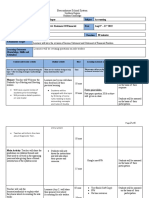

Table 1

The difference of the mean percent group score for Healthcare Providers for each time intervals using ANOVA.

Group Type

SS

Group 1 b3 months

Between

728

Within

392

Total

1120

Group 2 b6 months

Between

998

Within

200

Total

1198

Group 3 b9 months

Between

810

Within

16

Total

826

Group 4 b2 years

Between

1513

Within

592

Total

2105

Note the signicance level is 0.05.

df

MS

F-statistic

Signicance

7

2

9

104

196

0.53

.78

7

2

9

142

100

1.43

.48

7

2

9

116

8

14.4

.07

7

2

9

216

296

.73

.69

96

R. Everett-Thomas et al. / Applied Nursing Research 30 (2016) 9497

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

Our results showed that retention of detailed knowledge for adult

learners is difcult for skills that are rarely used regardless of the time

HCPs were trained using high-delity simulation. Individuals who

completed the exam closest to the time of training scored better on

the written exam. These scores were compared to individuals who did

not receive the training prior to taking the test or nearly one year after

training. Additionally, the total mean scores were not signicantly different from those who were tested two-years post simulation training.

The results suggest that many individuals retained only about 50% of

the information needed to successfully pass the CPR recertication examination. Likewise, the most frequently missed questions were related

to specic details of a particular procedure such as AED use (turn on the

device before using and resume CPR immediately after shocking the patient) or specic hand placement for compressions (on the lower half of

the breastbone and two inches deep). A high percentage of individuals

(85%) incorrectly answered the frequency in which a breath should be

given in the presence of an advanced airway. They also failed to recall

the physiology for chest compressions. Some of these individuals

missed the question related to the purpose of the appropriate depth of

compressions. Others had lower test scores because they did not

remember the pertinent information regarding BVM ventilation for

one and/or two rescuers. These results concur with previous research

that shows CPR knowledge diminishes substantially by three months

post-training unless it is a frequently used skill (Aqel & Ahmad, 2014;

Nori, Saghania, Motamedi, & Hosseini, 2012).

In a study of 90 nursing students, a positive increase in CPR knowledge and skills acquisition favored HFS training over traditional BLS

teaching methods. However, both groups decreased in knowledge and

skills after three months (Aqel & Ahmad, 2014). Nori et al. (2012) had

similar ndings for 112 nurses in which their CPR knowledge and skills

began to show a decrease as early as ten weeks post training. They also

showed a continued decline in both knowledge and skills two years

later. In a study of 78 residents (medical doctors) from nine different

specialties, retention of knowledge after simulation training was poor.

Then yet, the residents self-reported higher perceptions in performing

CPR in this study (Adekola et al., 2013).

The question remains: How do we train individuals to remember

vital sequential information for a procedure that they rarely perform

in their daily work environment? CPR educators and innovators imply

that automated systems may help providers and students remember

the sequence of skills. For example, in both a feasibility and preliminary

study, researchers demonstrated effective and efcient methods to

assess the retention of BLS knowledge and skills using automated CPR

training (Mpotos, De Wever, Valckle, & Monsieurs, 2012; Oreman

et al., 2010). They used an automated testing station to assess 181

medical residents retention of BLS skills six months after training.

Their results showed that the system was able to guide the students

accurately through the testing procedures (Mpotos et al., 2012).

Likewise, Oreman et al. (2010) used a CPR voice assisted mannequin

to help 264 nursing students perform the correct skills of CPR.

This was achieved by providing immediate verbal feedback to the

student while prompting them with corrective actions to improve

their performance.

These studies may predict a future training modality for HCPs in

retaining BLS knowledge and skills without the need of a live instructor.

Freestanding automated CPR stations in healthcare settings may allow

HCPs to practice at their own pace as often as needed. However, servicing these systems may become expensive. HFS has shown to have better

results for the retention of CPR knowledge and skills when compared to

standard training. HCPs continue to show a degradation in knowledge

over time regardless of their teaching modality. Thus, educators must

include strategies to evaluate CPR knowledge at frequent intervals

since the minimum requirements set by the AHA and healthcare organizations may be insufcient for HCPs.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the test was given

to HCPs during or immediately after their work day. Since no identiable information was collected, this may have resulted in a lack of concentration or focus on the exam. Second, the exam was given to all

available nurse and allied healthcare personnel from different specialties with varying levels of education. This mix of education levels may

have produced lower overall scores. Although the participants were

from ve different outpatient clinics, they were still considered to be

from one site (organization). Lastly, the small convenience sample size

was also a limitation.

6. Conclusion

High-delity simulation shows promise to help HCPs retain the

necessary knowledge to successfully perform CPR. Researchers have

shown that more frequent sessions may be required. Since training

large numbers of HCPs can become expensive for any organization,

automated CPR stations may prove to be less expensive and benecial

in the near future. As these systems can be used and incorporated into

any training modality, healthcare organizations should consider

using them. Instructors and researchers must continue to assess the

effectiveness of various CPR training modalities on sustained knowledge

by testing participants at frequent intervals.

6.1. Future implications

With more than fty years of mandatory basic life support training,

HCPs continue to struggle in retaining CPR knowledge and skills. Lives

are lost in non-acute healthcare facilities due to HCPs apprehension

and other barriers related to initiating CPR. Some of these barriers

may become more noticeable due to on-line access of the written

exam. Educators and researchers should support the notion of providing

mandatory spot checks of CPR knowledge by administering the written

exam at frequent intervals within the recertication period.

References

Ackermann, A. D. (2009). Investigation of learning outcomes for the acquisition and

retention of CPR knowledge and skills learned with the use of high-delity simulation.

Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 5(6), 213222.

Adekola, O. O., Menkiti, D. I., & Desalu, I. (2013). How much do we remember after CPR

training? Experience from a Sub-Saharan teaching hospital. Analgesia & Resuscitation:

Current Research. http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2324-903x.s1-009.

Aqel, A. A., & Ahmad, M. M. (2014). High delity simulation effects on CPR knowledge,

skills, acquisition and retention in nursing students. Worldviews on Evidence-Based

Nursing, 11(6), 394400.

Al Hadid, L., & Suleiman, K. (2012). Effect of boost simulated sessions on CPR competency

among nursing students: A pilot study. Journal of Education and Practice, 3(16),

186193.

American Heart Association (). The American Heart Association published the Heart

Disease and Stroke Statistics- 2013 Update online on December 12, 2012. http://

www.heart.org/HEARTORG/General/Cardiac-Arrest-Statistics_UCM_448311_Article.

jsp (Retrieved on March 2013)

Chee, J. (2014). Clinical simulation using deliberate practice in nursing education:

A Wilsonian concept Analysis. Nurse Education in Practice, 14, 247252.

Issenberg, S. B., & Scalese, R. (2007). Simulation in healthcare education. Perspectives

in Biology and Medicine, 51, 3136.

Mpotos, N., De Wever, B., Valckle, M. A., & Monsieurs, K. G. (2012). Assessing basic life

support skills without an instructor: Is it possible? BMC Medical Education, 12, 85.

Niles, D. E., Sutton, R. M., Nadkarnia, V. M., Glatzd, A., Zuerchere, M., Maltese, M. R., ... Berg, R. A.

(2011). Prevalence and hemodynamic effects of leaning during CPR. Resuscitation, 82(0 2),

S23S26.

Nevin, M., Neill, F., & Mulkerrins, J. (2014). Preparing the nursing student for internship in

a pre-registration nursing program: Developing a problem based approached with

the use of high delity simulation equipment. Nurse Education in Practice, 14,

154159.

Nori, M. J., Saghania, M., Motamedi, M. H. K., & Hosseini, S. M. K. (2012). CPR training

for nurses: How often is it necessary? Iran Red Crescent Medical Journal, 14(2),

104107.

Oreman, M. H., Kardong-Edgren, S., Odom-Maryon, T., Ha, Y., McColgan, J., Hurd, D., ...

Dowdy, S. W. (2010). HeartCode BLS with voice assisted manikin for teaching

nursing students: Preliminary results. Nursing Education Perspectives, 31(5), 303308.

R. Everett-Thomas et al. / Applied Nursing Research 30 (2016) 9497

Sankar, J., Vijayakanthi, N., Sankar, M. J., & Dubey, N. (2013). Knowledge and skill retention of

in-service versus preservice nursing professional following an informal training program

in pediatric cardiopulmonary resusciation: A repeated-measures quasiexperimental

study. Biomed Research International. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/403415.

97

Tawalbeh, L., & Tubaishat, A. (2013). Effect of simulation on knowledge of advance

cardiac life support, knowledge, retention, and condence of nursing students

in Jordan. Journal of Nursing Education, 52. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/014843420131218-01.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Week 5Dokument28 SeitenWeek 5KhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Unit Normal Vector Is Denoted byDokument20 SeitenUnit Normal Vector Is Denoted byKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Week 4Dokument8 SeitenWeek 4KhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- 3.2.3 Newton's Divided Difference Interpolation: Lagrange Method Has The Following WeaknessesDokument31 Seiten3.2.3 Newton's Divided Difference Interpolation: Lagrange Method Has The Following WeaknessesKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- 3.4 Numerical Solution of Differential EquationsDokument21 Seiten3.4 Numerical Solution of Differential EquationsKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Week 6Dokument23 SeitenWeek 6KhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Tradable News ReportsDokument10 SeitenTradable News ReportsKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- 1 s2.0 S1877050914003676 MainDokument11 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877050914003676 MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A: Irène BuvatDokument7 SeitenNuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A: Irène BuvatKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Item Analysis Subjective With OptionDokument18 SeitenItem Analysis Subjective With OptionKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- 3 Construction of MCQDokument14 Seiten3 Construction of MCQKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- 2 Bloom's Taxonomy and Test BlueprintDokument25 Seiten2 Bloom's Taxonomy and Test BlueprintKhairul100% (3)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- 4 Construction of Subjective ItemsDokument15 Seiten4 Construction of Subjective ItemsKhairul100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Assessment Methods: Vincent Pang Universiti Malaysia SabahDokument10 SeitenAssessment Methods: Vincent Pang Universiti Malaysia SabahKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- 1 Assessment PrinciplesDokument25 Seiten1 Assessment PrinciplesKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal LinkDokument1 SeiteJournal LinkKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Kernel RBF PaperDokument7 SeitenKernel RBF PaperKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scripta Materialia: S.V. Starikov, L.N. KolotovaDokument4 SeitenScripta Materialia: S.V. Starikov, L.N. KolotovaKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Eula Microsoft Visual StudioDokument3 SeitenEula Microsoft Visual StudioqwwerttyyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0043135415303250 MainDokument9 Seiten1 s2.0 S0043135415303250 MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0376738815301186 MainDokument14 Seiten1 s2.0 S0376738815301186 MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Computer Simulations To Maximise Fuel Efficiency and Work Performance of Agricultural Tractors in Rotovating and Ploughing OperationsDokument11 SeitenComputer Simulations To Maximise Fuel Efficiency and Work Performance of Agricultural Tractors in Rotovating and Ploughing OperationsKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1552526015023687 MainDokument1 Seite1 s2.0 S1552526015023687 MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0927025615006230 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S0927025615006230 MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S026069171500461X MainDokument3 Seiten1 s2.0 S026069171500461X MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0010465515003483 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S0010465515003483 MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1876139915000900 MainDokument6 Seiten1 s2.0 S1876139915000900 MainKhairulNoch keine Bewertungen

- LO170 - 46C - 003basicsDokument28 SeitenLO170 - 46C - 003basicsmkumarshahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Teachers' Perception Towards The Use of Classroom-BasedDokument16 SeitenTeachers' Perception Towards The Use of Classroom-BasedDwi Yanti ManaluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrons and PhotonsDokument48 SeitenElectrons and PhotonsVikashSubediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding & Predicting E-Commerce Adoption: An Extension of The Theory of Planned BehaviorDokument13 SeitenUnderstanding & Predicting E-Commerce Adoption: An Extension of The Theory of Planned BehaviorANISANoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.yontef, G. (1993) .Awareness, Dialogueandprocess - Essaysongestalttherapy - NY - TheGestaltJournal Press. Chapter6 - Gestalt Therapy - Clinical Phenomenology pp181-201.Dokument12 Seiten1.yontef, G. (1993) .Awareness, Dialogueandprocess - Essaysongestalttherapy - NY - TheGestaltJournal Press. Chapter6 - Gestalt Therapy - Clinical Phenomenology pp181-201.nikos kasiktsisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Admission (If Simulation Is Done by 3rd Person)Dokument2 SeitenAffidavit of Admission (If Simulation Is Done by 3rd Person)AlyssaCabreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coach CarterDokument3 SeitenCoach Cartermichael manglicmotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Percentage Sheet - 04Dokument2 SeitenPercentage Sheet - 04mukeshk4841258Noch keine Bewertungen

- Leroy AMIA Poster 1 PageDokument2 SeitenLeroy AMIA Poster 1 PagedivyadupatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Map Document 2015-06-03Dokument12 SeitenMap Document 2015-06-03AjayRampalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diego Gallo Macin Janet Santagada Eac 150 NBQ 09. Mar. 2018 Research Skills AssignmentDokument5 SeitenDiego Gallo Macin Janet Santagada Eac 150 NBQ 09. Mar. 2018 Research Skills AssignmentDiego Gallo MacínNoch keine Bewertungen

- TABLE OF CONTENTS FINAL - 2ndDokument10 SeitenTABLE OF CONTENTS FINAL - 2ndKaren CobachaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Task Sheet No. 5 (Done)Dokument6 SeitenTask Sheet No. 5 (Done)Do Lai NabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Exam Gen Bio 1Dokument4 SeitenFinal Exam Gen Bio 1Joderon NimesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learn OSMDokument3 SeitenLearn OSMJulian Lozano BrauNoch keine Bewertungen

- RObbinsDokument37 SeitenRObbinsapi-374646950% (4)

- Study To Fly ATP Flight Schoolwzuiw PDFDokument1 SeiteStudy To Fly ATP Flight Schoolwzuiw PDFMayerOh47Noch keine Bewertungen

- PDFDokument827 SeitenPDFPrince SanjuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final English Hiragana BookletDokument18 SeitenFinal English Hiragana BookletRoberto MoragaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Placement Goals-2Dokument1 SeiteFinal Placement Goals-2api-466552053Noch keine Bewertungen

- BMus MMus DipDokument67 SeitenBMus MMus Dipdotknow100% (1)

- Geology of The Cuesta Ridge Ophiolite Remnant Near San Luis Obispo, California: Evidence For The Tectonic Setting and Origin of The Coast Range OPhioliteDokument149 SeitenGeology of The Cuesta Ridge Ophiolite Remnant Near San Luis Obispo, California: Evidence For The Tectonic Setting and Origin of The Coast Range OPhiolitecasnowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tarone and LiuDokument22 SeitenTarone and LiuGiang NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voula Tsouna - Plato's Charmides - An Interpretative Commentary-Cambridge University Press (2022)Dokument355 SeitenVoula Tsouna - Plato's Charmides - An Interpretative Commentary-Cambridge University Press (2022)jmediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lessonn Plan Accounting Class 11 Week 2Dokument4 SeitenLessonn Plan Accounting Class 11 Week 2SyedMaazAliNoch keine Bewertungen

- MR Homework Florante at LauraDokument5 SeitenMR Homework Florante at Lauracfcseybt100% (1)

- Exemplary Leadership EssayDokument8 SeitenExemplary Leadership Essayapi-312386916100% (1)

- Investing in The 21 Century Skilled Filipino WorkforceDokument72 SeitenInvesting in The 21 Century Skilled Filipino WorkforceRhemz Guino-oNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gender and Leadership Wars: Gary N. PowellDokument9 SeitenThe Gender and Leadership Wars: Gary N. PowellACNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Questions Nclex-: Delegation For PNDokument5 SeitenNursing Questions Nclex-: Delegation For PNsaxman011Noch keine Bewertungen