Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Andrei Nasta - The Philosophy of Generative Linguistics

Hochgeladen von

Guilherme Sanches de OliveiraCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Andrei Nasta - The Philosophy of Generative Linguistics

Hochgeladen von

Guilherme Sanches de OliveiraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by: [Georgia State University]

On: 22 November 2013, At: 12:49

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Philosophical Psychology

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cphp20

The Philosophy of Generative

Linguistics

Andrei Nasta

University of East Anglia, School of Philosophy , 14 Needham

Place, St. Stephen's Square, Norwich , Norfolk , NR1 3SD , UK

Published online: 03 May 2013.

To cite this article: Andrei Nasta , Philosophical Psychology (2013): The Philosophy of Generative

Linguistics, Philosophical Psychology, DOI: 10.1080/09515089.2013.791746

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2013.791746

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or

arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

Philosophical Psychology, 2013

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2013.791746

Downloaded by [Georgia State University] at 12:49 22 November 2013

Book Review

The Philosophy of Generative Linguistics

Peter Ludlow

New York: Oxford University Press, 2011

240 pages, $55.00, ISBN: 0199258538 (hbk)

The work under review develops numerous traditional philosophical themes such as

externalism, skepticism, color, and simplicity as they arise in theoretical linguistics,

especially in linguistic syntax and semantics. With an important exception

(the externalist metaphysics), the thrustperhaps the strengthof the book is

broadly methodological. The book purports to motivate the generative linguistic

enterprise and to fight some potential misconceptions such as the claim that linguistic

intuitions are unreliable sources of data or that certain linguistic proposals are lacking in

formal rigor or simplicity. In the present review, I shall focus on two important themes

of the work, one pertaining to the metaphysics of linguistics (covered in chapters 5

and 6) and the other pertaining to the methodology of linguistics (treated in chapter 7).

After dealing with certain worries about linguistic intuitions (chapters 2 and 3),

Ludlow discusses two types of skeptical claims that linguistics is faced with. The first one

is inspired by Quines indeterminacy of translation argument. The worry is roughly that

grammar, i.e., the competence system mentally realized by competent speakers, is

underdetermined by the data. The second worry is that grammar is a system of rules

whose explanatory status is problematic because, as Kripke (1982) argued in developing

a Wittgensteinian line, there is no fact of the matter as to which rule is being followed.

Let us focus on the so-called determination question of the Kripke Wittgenstein

skeptical argument. Kripkes skeptic invites us to assume the intuitive view that we

know the rule of addition and that we have a past history of successful additions (or of

addition rule following). Then he asks us to invoke a fact that determines that what we

took to be addition in the past is actually addition and not an anomalous operation

that resembles addition on a given domain (of past applications) but differs from it on

an arbitrary extension of that domain (the domain of future applications). But, the

skeptic argues, no matter what fact we invokedispositions to add, platonic entities,

addition machinesthere is still a way in which we didnt determine the rule of

addition. Therefore, rule following is problematic. Since generative linguistics assumes

that linguistic structures are generated by applications of rules (cognitively realized),

generative linguistics has a foundational problem.

Ludlow endorses an argument (due to Soames, 1998) according to which the

skeptical reasoning is not sound. The mistake is that the skeptic equivocates between

Downloaded by [Georgia State University] at 12:49 22 November 2013

Book Review

an epistemic and a metaphysical understanding of determination (see pp. 115 117 for

details). Ludlow further suggests that the anti-skeptical solution supports externalism

about the individuation of (linguistic) syntactic facts. However, it is not clear to me

that anti-skepticism supports externalism, since the internalist may avail herself of the

same anti-skeptical strategy.

Syntactic externalism is the thesis that the environment partly determines the

syntactic (and computational) structure of linguistic utterances via a causal link

(pp. 117 118; see also pp. 47 48). Ludlow proposes that syntactic externalism has a

useful application to the problem of empty proper names. Empty proper names are a

vexed problem in philosophy of language: utterances containing such names do not

seem to have truth-conditions, because there is no object serving as semantic value for

empty names. Since truth-conditions are the basis for assigning meaning to such

utterances, it follows that they are meaningless. But we can avoid this problematic

consequence. Pace Ludlow, if syntax supervenes in part on the environmental

conditions, it is plausible that the missing bit of syntax, which contributes in part the

needed truth-conditions of utterances containing empty names, is determined by the

environment. Thus, whether the speaker/hearer realizes it or not, the environment

determines the syntactic structure of a definite description in the logical form of the

utterances containing empty names. The utterances of non-empty names will have the

simpler syntax specific to referential expressions.

Now this kind of externalism, Ludlow acknowledges, is an extremely bold thesis

(several objections are answered on p. 117). I shall mention two additional worries.

I find the account of the syntax of empty names problematic on two counts. First, it

implies that the syntactic structure of expressions of the same type (i.e., what we

usually call proper names) can be realized in two ways, internally in the grammar,

and externally by the intervention of the environment. But, after all, we can make the

(syntactic) distinction between names and definite descriptions on independent

grounds, and this presumably is not due to the environment (otherwise any bit of

syntactic structure would depend on the environment). Why should the syntax of

names and descriptions supervene sometimes on external facts and sometimes on

internal facts? Instead of accepting this complication in the account of grammatical

competence, it would be more plausible to adopt another solution to the empty names

problem, a solution that assumes a uniformly realized grammar and gets the truthconditions right at the same time. Ludlow mentions two such plausible solutions: the

gappy proposition view and the non-existent objects view.

Second, and more importantly, the problem with syntactic externalism is its lack of

empirical motivation. Ludlow mentions that the syntactic distinction between empty

proper names and non-empty ones may affect the predictions about entailment

relations, the modal profile of these sentences (p. 125) that an omniscient agent may

have access to. However, no linguistic argument has been provided for the claim that

sentences involving proper names have the special syntactic modal profile postulated

by syntactic externalism. Its worth stressing that the problem is not about extragrammatical factors having effects on grammar. Indeed, the claim that there is some

sort of dependence of logical forms on extra-syntactic factors is not new to linguistics

Downloaded by [Georgia State University] at 12:49 22 November 2013

Book Review

(see especially work within the Minimalist Program: Chomsky, 1995; Reinhart, 2006).

The trouble with syntactic externalism is that no linguistic phenomenon seems to

support it. So, what has yet to be shown is that the (externalist) syntax of proper names

can be tracked by the usual linguistic tests.

Let us turn next to the methodological discussion, whose aim is to formulate adequate

theory choice criteria for linguistics. I shall focus on simplicity. The absolute notion of

simplicity, I take it, is something akin to the less is more principle, paired with the

claim that there are objective ways of determining what less means (i.e., what is the

quantity to be minimized). Ludlow argues (p. 152) that the usage of the absolute notion

of simplicity, also cast as aiming to reduce the theoretical machinery, is hopelessly

indeterminate and context sensitive. Simply put, a reduction (of the theoretical

machinery) in one part of the theory may lead to an augmentation in another part. Then,

depending on how we fix the background of evaluation, simplicity will recommend

contradictory decisions about the preferable linguistic hypothesis. In contrast, Ludlow

argues, the notion of simplicity as ease of use is less restrictive than the absolute one,

and less prone to misfire. Rephrasing somewhat Ludlows characterization of simplicity

(pp. 161162), we may state his more liberal notion as follows:

Ease of Use Simplicity: Simplicity varies both with the theorist or research

community and with time. Rational theorists will gravitate towards simpler theories

because they are easier to use (formulate, calculate, understand, and communicate).

Thus stated, the notion seems to be fairly commonsensical. But it is also pretty

indeterminate for theoretical purposes. In particular, this notion makes it obscure what

simplicity is and in which ways it can play a normative role in theory choice. This may be

consistent with Ludlows intent, since he seems to think that there is no way to spell out a

useful principle of simplicity that normatively guides theory construction and theory

choice. Otherwise put, there is no interesting theoretical notion of simplicity beyond the

liberal one. Note that it is this latter assumption (argued for on p. 152) that is

inconsistent with the notion of absolute simplicity, not the liberal ease of use notion.

A more serious worry is that ease of use notion has a relativist flavor. For various

psychological and sociological reasons, the theory that a scientist uses at a certain

moment may be classified as the easiest to use and thus the simplest, even if the theory

may otherwise be unnecessarily complicated. It is only the assumption of rationality

built into the liberal notion of simplicity that rules out such a possibility. But then the

notion turns out to be trivial. In either case, the ease of use notion of simplicity misses

(or simply glosses over) the normative aspect of simplicity, which seems essential to a

theoretical virtue. Let me sketch a perspective that does not have this problem. The

absolute notion of simplicity, seen as a function that minimizes some quantity (e.g.,

axioms, strings of symbols, etc.) gives us a concrete way to think about simplicity. In

particular, it makes it clear why we should prefer a theory to another in certain cases.

It is true that the assessment of simplicity (i) may change with what we contextually

take to be the relevant quantity, and that (ii) assessing the simplicity of whole theories

is very often intractable. However, beginning with (ii), the relevance of the notion of

Downloaded by [Georgia State University] at 12:49 22 November 2013

Book Review

simplicity does not depend only on the tractability of inter-theoretical comparisons.

The apparent intractability does not mean that efforts to reach simpler theories are not

legitimate, or, further, that they are not causally efficient in determining simple results,

over time. On the liberal view, simplicity is something to be found over time, without

seeking for it, as if by magic. Moreover, regarding (i), context sensitivity is a problem

only if we assume that linguistic hypotheses should be simple in all respects; but this

should not be so: a hypothesis can be simple in some respects important to the scientist,

and it can be absolutely so, even if it is not simple in other respects. Thus the relevant

background of evaluation of absolute simplicity may also be fixed relative to the

theorist (for an attempt to capture the normativity of simplicity within the general

philosophy of science see Kelly, 2007; for a different take on simplicity within the

philosophy of linguistics see Collins, 2012).

In closing, I hasten to mention that the book contains several other interesting

themes: the epistemic role of linguistic intuitions, the externalist semantics, and the

notion of formal rigor are cases in point. There are many novel discussions (like the one

on the normativity of grammar). I found Ludlows epistemological discussion (not

touched on here) particularly convincing. However, I think that Ludlows syntactic

externalist thesis suffers from lack of empirical motivation. Finally, the discussion of

theory choice criteria made a prima facie case for a liberal understanding of simplicity

and formal rigor in linguistics that further studies should build on or compete with. In

conclusion, I think this is a valuable addition to the philosophy of linguistics literature,

and philosophers interested in linguistics would surely benefit from reading it.

References

Chomsky, N. (1995). The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Collins, J. (2012). The unity of linguistic meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kelly, K. (2007). A new solution to the puzzle of simplicity. Philosophy of Science, 74(5), 561 573.

Kripke, K. (1982). Wittgenstein on rules and private language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Reinhart, T. (2006). Interface strategies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Soames, S. (1998). Skepticism about meaning: Indeterminacy, normativity, and the rule-following

paradox. In A. Kazmi (Ed.), Canadian Journal of Philosophy: Suppl. Vol. 23. Meaning and

reference (pp. 211 250). Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

Andrei Nasta

University of East Anglia, School of Philosophy

14 Needham Place, St. Stephens Square, Norwich

Norfolk NR1 3SD, UK

Email: A.Nasta@uea.ac.uk

q 2013 Andrei Nasta

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2013.791746

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

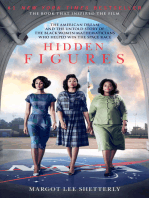

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Music Education (Kodaly Method)Dokument4 SeitenMusic Education (Kodaly Method)Nadine van Dyk100% (2)

- Why-Most Investors Are Mostly Wrong Most of The TimeDokument3 SeitenWhy-Most Investors Are Mostly Wrong Most of The TimeBharat SahniNoch keine Bewertungen

- School Based CPPDokument11 SeitenSchool Based CPPjocelyn g. temporosa100% (1)

- 211 N. Bacalso Avenue, Cebu City: Competencies in Elderly CareDokument2 Seiten211 N. Bacalso Avenue, Cebu City: Competencies in Elderly CareScsit College of NursingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Norman 2017Dokument7 SeitenNorman 2017Lee HaeunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Đại Từ Quan Hệ Trong Tiếng AnhDokument5 SeitenĐại Từ Quan Hệ Trong Tiếng AnhNcTungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mount Athos Plan - Healthy Living (PT 2)Dokument8 SeitenMount Athos Plan - Healthy Living (PT 2)Matvat0100% (2)

- BurnsDokument80 SeitenBurnsAlina IlovanNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Qbasic (Algorithm) : By: Nischit P.N. Pradhan Class: 10'B To: Prakash PradhanDokument6 SeitenOn Qbasic (Algorithm) : By: Nischit P.N. Pradhan Class: 10'B To: Prakash Pradhanapi-364271112Noch keine Bewertungen

- Presente Progresive TenseDokument21 SeitenPresente Progresive TenseAriana ChanganaquiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSC Nastran 20141 Install GuideDokument384 SeitenMSC Nastran 20141 Install Guiderrmerlin_2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Electronic Devices and Electronic Circuits: QuestionsDokument51 SeitenElectronic Devices and Electronic Circuits: QuestionsRohit SahuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diverse Narrative Structures in Contemporary Picturebooks: Opportunities For Children's Meaning-MakingDokument11 SeitenDiverse Narrative Structures in Contemporary Picturebooks: Opportunities For Children's Meaning-MakingBlanca HernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using NetshDokument2 SeitenUsing NetshMohcin AllaouiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mohit Maru 4th Semester Internship ReportDokument11 SeitenMohit Maru 4th Semester Internship ReportAdhish ChakrabortyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Character Skills Snapshot Sample ItemsDokument2 SeitenCharacter Skills Snapshot Sample ItemsCharlie BolnickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elements of Visual Design in The Landscape - 26.11.22Dokument15 SeitenElements of Visual Design in The Landscape - 26.11.22Delnard OnchwatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Worksheet WH QuestionsDokument1 SeiteWorksheet WH QuestionsFernEspinosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical Report WritingDokument21 SeitenTechnical Report WritingMalik JalilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winifred Breines The Trouble Between Us An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in The Feminist MovementDokument279 SeitenWinifred Breines The Trouble Between Us An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in The Feminist MovementOlgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hanssen, Eirik.Dokument17 SeitenHanssen, Eirik.crazijoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Histology Solution AvnDokument11 SeitenHistology Solution AvnDrdo rawNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLL Template MathDokument3 SeitenDLL Template MathVash Mc GregorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occupant Response To Vehicular VibrationDokument16 SeitenOccupant Response To Vehicular VibrationAishhwarya Priya100% (1)

- Measurement (Ques - Ch2 - Electromechanical Instruments) PDFDokument56 SeitenMeasurement (Ques - Ch2 - Electromechanical Instruments) PDFmadivala nagarajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AVEVA Work Permit ManagerDokument2 SeitenAVEVA Work Permit ManagerMohamed Refaat100% (1)

- Yahoo Tab NotrumpDokument139 SeitenYahoo Tab NotrumpJack Forbes100% (1)

- Cambridge IGCSE: BIOLOGY 0610/31Dokument20 SeitenCambridge IGCSE: BIOLOGY 0610/31Balachandran PalaniandyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer AnalysisDokument6 SeitenCustomer AnalysisLina LambotNoch keine Bewertungen

- NAT FOR GRADE 12 (MOCK TEST) Language and CommunicationDokument6 SeitenNAT FOR GRADE 12 (MOCK TEST) Language and CommunicationMonica CastroNoch keine Bewertungen