Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

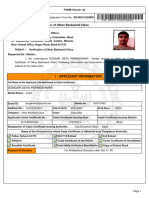

Cases Property

Hochgeladen von

Terence ValdehuezaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cases Property

Hochgeladen von

Terence ValdehuezaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PROPERTY CASES

prove respondents allegation of prior physical

possession.

MARCELA M. DELA CRUZ, Petitioner, v.

ANTONIO Q. HERMANO AND HIS WIFE

REMEDIOS HERMANO, Respondents.

G.R. No. 160914

March 25, 2015

FACTS: Respondents Antonio Hermano and his

wife Remedios Hermano were the registered and

lawful owners of a house and lot in Tagaytay City.

On September 1, 2001, petitioner Marcela M.

Dela Cruz occupied and possessed the

questioned property pursuant to the alleged

Memorandum of Agreement between her and a

certain Don Mario Enciso Benitez, without the

authority and consent of the Hermanos. On

September 27, 2001, A. Hermano, through a

counsel, sent a formal demand letter to Dela

Cruz to vacate and turn over the possession of

the property and to pay P 20,000 a month as

rent starting September 1, 2001.

Respondent filed an ejectment case against the

petitioner at the MTCC; however, the court

dismissed the case due to lack of jurisdiction.

The court also stated that respondents proper

remedy should be an action for recovery and not

of a summary proceeding for ejectment, because

there was no showing of forcible entry or

unlawful detainer.

Respondent appealed the decision at the RTC;

the said court, however, affirmed the decision of

the lower court en toto. The same filed a petition

for review at the CA, of which, granted the

petition, reversed and set aside the decision of

RTC. Furthermore, the court rendered a decision

declaring Hermano as the lawful possessor of the

property and order Dela Cruz to vacate the

same. With the CAs decision, petitioner filed a

petition for review at the Supreme Court.

ISSUE: Whether or not respondent has

adequately pleaded and proved a case of forcible

entry.

HELD: The burden of sufficiently alleging prior

physical

possession

carries with it the

concomitant burden of establishing ones case

by a preponderance of evidence. To be able to do

so, respondents herein must rely on the strength

of their own evidence, not on the weakness of

that of petitioner. It is not enough that the

allegations of a complaint make out a case for

forcible entry. The plaintiff must prove prior

physical possession. It is the basis of the security

accorded by law to a prior occupant of a property

until a person with a better right acquires

possession thereof.

The

Court

has

scrutinized

the

parties

submissions, but found no sufficient evidence to

To prove their claim of having a better right to

possession, respondents submitted their title

thereto and the latest Tax Declaration prior to

the initiation of the ejectment suit. As the CA

correctly observed, petitioner failed to controvert

these documents with competent evidence. It

erred, however, in considering those documents

sufficient to prove respondents prior physical

possession.

Ownership certainly carries the right of

possession, but the possession contemplated is

not exactly the same as that which is in issue in

a forcible entry case. Possession in a forcible

entry suit refers only to possession de facto, or

actual or material possession, and not one

flowing out of ownership. These are different

legal concepts under which the law provides

different remedies for recovery of possession.

Thus, in a forcible entry case, a party who can

prove prior possession can recover the

possession even against the owner. Whatever

may be the character of the possession, the

present occupant of the property has the

security to remain on that property if the

occupant has the advantage of precedence in

time and until a person with a better right

lawfully causes eviction.

Similarly, tax declarations and realty tax

payments are not conclusive proofs of

possession. They are merely good indicia of

possession in the concept of owner based on the

presumption that no one in ones right mind

would be paying taxes for a property that is not

in ones actual or constructive possession.

Guided by the foregoing, the Court finds that the

proofs

submitted

by

respondents

only

established possession flowing from ownership.

Although respondents have claimed from the

inception of the controversy up to now that they

are using the property as their vacation house,

that claim is not substantiated by any

corroborative evidence. On the other hand,

petitioners claim that she started occupying the

property in March 2001, and not in September of

that year as Antonio alleged in his Complaint,

was corroborated by the Affidavit of petitioners

caretaker. Respondents did not present any

evidence to controvert that affidavit.

Therefore, respondents failed to discharge their

burden of proving the element of prior physical

possession. Their uncorroborated claim of that

fact, even if made under oath, is self-serving. It

does not amount to preponderant evidence,

which simply means that which is of greater

weight or is more convincing than evidence that

is offered in opposition.

As noted at the outset, it bears stressing that the

PROPERTY CASES | Digested by Terence Valdehueza And Mia Unabia

Court is not a trier of facts. However, the

conflicting findings of fact of the MTCC and the

RTC, on the one hand, and the CA on the other,

compelled us to revisit the records of this case

for the proper dispensation of justice. Moreover,

it must be stressed that the Courts

pronouncements in this case are without

prejudice to the parties right to pursue the

appropriate remedy.

WHEREFORE, the Petition for Review on

Certiorari is hereby GRANTED. The assailed

Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals

are REVERSED, and the Decision of the MTCC

dismissing the Complaint against petitioner

is REINSTATED.

JOSEFINA V. NOBLEZA, Petitioner, v. SHIRLEY

B. NUEGA, Respondent.

G.R. No. 193038

March 11, 2015

FACTS: Respondent Shirley Nuega, an OFW

working as a domestic helper in Israel, was

married to Rogelio Nuega on September 1, 1990.

On 1988, prior to their marriage, Shirley financed

Rogelio in buying a house and lot in Marikina.

The same was purchased by Rogelio on

September 1989 and was registered on October

1989 under his sole name.

The couple then moved to their new home after

their marriage in September 1990. Then after,

Shirley returned to Israel. While at overseas, she

learned about extra-marital affairs of her

husband, and it was confirmed upon her return

that she was living and having an affair with a

certain Monica Escobar in the same property.

In June 1992, Shirley filed two cases against

Rogelio: one for Concubinage and another for

Legal Separation and Liquidation of Property.

Shirley withdraw the latter complaint but later

re-filed the same. In between the filing of the

cases, Shirley learned that Rogelio had the

intention of selling the subject property. Shirley

then advised the interested buyersone was their

neighbor and the other was the petitionerof the

existence of the cases that she had filed against

Rogelio and cautioned them against buying the

subject property until the cases are closed and

terminated. Nonetheless, under a Deed of

Absolute Sale dated December 29, 1992, Rogelio

sold the subject property to petitioner without

Shirley's consent for 380,000 pesos, including

petitioner's undertaking to assume the existing

mortgage on the property and to pay the real

property taxes due thereon.

On May 16, 1994, the RTC granted the petition

for legal separation and ordered the dissolution

and liquidation of the regime of absolute

community of property between Shirley and

Rogelio. Rogelio appealed the ruling before the

CA which denied due course and dismissed the

petition. It became final and executory and a writ

of execution was issued in August 1995.

On August 27, 1996, Shirley instituted a

Complaint for Rescission of Sale and Recovery of

Property against petitioner and Rogelio before

the RTC. After trial on the merits, the trial court

rendered the sale of Shirleys portion being null

and void; ordered Nobleza to reconvey or pay

Shirley with that of her share; and ordered the

same to pay for the latters attorneys fees.

Petitioner sought recourse with the CA, while

Rogelio did not appeal the ruling of the trial

court. In its assailed Decision promulgated on

May 14, 2010, the appellate court affirmed with

modification the trial court's ruling that the

property should entirely be reconveyed to the

Shirley and Rogelio.

Petitioner moved for reconsideration. In a

Resolution dated July 21, 2010, the appellate

court denied the motion for lack of merit. Hence,

the reason of filing a petition questioning errors

that the courts may have made.

ISSUE: Whether or not the CA erred when it

affirmed the decision of the RTC by sustaining

the finding that the petitioner was not a

purchaser in good faith.

HELD: Petitioner is not a buyer in good faith.

Even if the petitioner had contended that she

had examined the Transfer Certificate of Title

over the subject property, the court held that

merely relying on the same while ignoring all

other surrounding circumstances relevant to the

sale.

Moreover, the court held that she did not

exercise prudence. For at the time of the sale,

her sister was residing at the same Village where

the property was situated. She could have easily

checked if Rogelio has the capacity to dispose

the property. The respondent had even warned

her neighbors in the Village, including her sister,

not to engage in any deal with her husband

because there are pending cases filed against

him.

Another were the issues surrounding the

execution of the Deed of Absolute Sale had also

pose question on the claim of petitioner that she

is a buyer in good faith. As correctly observed by

both courts, the Deed of Absolute Sale was

executed and dated on December 29, 1992.

However, the Community Tax Certificates of the

witnesses therein were dated January 2 and 20,

1993. While this irregularity is not a direct proof

of the intent of the parties to the sale to make it

appear that the Deed of Absolute Sale was

executed on December 29, 1992 or before

Shirley filed the petition for legal separation on

January 29, 1993it is circumstantial and

PROPERTY CASES | Digested by Terence Valdehueza And Mia Unabia

relevant to the claim of herein petitioner as an

innocent purchaser for value. In addition to

those, in the Deed of Absolute Sale dated

December 29, 1992, the civil status of Rogelio as

seller was not stated, while petitioner as buyer

was indicated as "single. It puzzles the Court

that while petitioner has repeatedly claimed that

Rogelio is "single" under the Transfer Certificate

of Title and two tax declarations, his civil status

as seller was not stated in the Deed of Absolute

Sale - further creating a cloud on the claim of

petitioner that she is an innocent purchaser for

value.

which, in turn, is a form of a stream; therefore,

belonging to the public dominion. It said that

petitioner could not close its eyes or ignore the

fact, which is glaring in its own title, that the 3meter strip was indeed reserved for public

easement. By relying on the Transfer Certificate

of Title it is then estopped from claiming

ownership and enforcing its supposed right.

Unlike the trial court, however, the CA noted that

the proper party entitled to seek recovery of

possession of the contested portion is not the

City of Las Pias, but the Republic of the

Philippines, through the SG, pursuant to Section

101 of C.A. No. 141.

PILAR

DEVELOPMENT

CORPORATION,

Petitioner, v. RAMON

DUMADAG,

et

al, Respondents.

G.R. No. 194336

March 11, 2013

The motion for reconsideration filed by petitioner

was denied by the CA per Resolution dated

October 29, 2010, hence, this petition.

FACTS: On July 1, 2002, petitioner filed a

complaint for accion publiciana with damages

against respondents for allegedly building their

shanties, without its knowledge and consent, in

Pilar Village Subd situated in Las Pias City. The

petitioner claims that said parcel of land, which

is duly registered in its name, was designated as

an open space of Pilar Village Subd intended for

village recreational facilities and amenities for

subdivision residents. In their Answer with

Counterclaim, respondents denied the material

allegations of the Complaint and briefly asserted

that it is the local government, not petitioner,

which has jurisdiction and authority over them.

Trial ensued. Both parties presented their

respective witnesses and the trial court

additionally conducted an ocular inspection of

the subject property. On May 30, 2007, the trial

court dismissed petitioner's complaint, finding

that the land being occupied by respondents are

situated on the sloping area going down and

leading towards the Mahabang Ilog Creek and

within the three-meter legal easement; thus,

considered as public property and part of public

dominion, which could not be owned by

petitioner.

The

trial

court

opined

that

respondents have a better right to possess the

occupied lot, since they are in an area reserved

for public easement purposes and that only the

local government of Las Pias City could institute

an action for recovery of possession or

ownership.

Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration, but

the same was denied by the trial court in its

Order dated August 21, 2007. Consequently,

petitioner elevated the matter to the Court of

Appeals which, on March 5, 2010, sustained the

dismissal of the case.

Referring to Section 2 of A.O. No. 99-21 of the

DENR, the appellate court ruled that the 3-meter

area being disputed is located along the creek

ISSUE: Whether or not Pilar Development

Corporation is entitled to the lawful possession of

the 3-meter easement, as provided by Art. 630

of the New Civil Code.

HELD: The court ruled that Pilar Development

Corporation is not lawfully entitled to the 3meter easement. This is because, according to

the lands Transfer Certificate of Title the said

easement has a reservation, to wit:

That the 3.00 meter strip of the lot

described herein along the Mahabang Ilog

Creek is reserved for public easement

purposes and to limitations imposed by

RA No. 440.

Also, though Art. 630 of the New Civil Code

provides for the general rule that "the owner of

the servient estate retains the ownership of the

portion on which the easement is established,

and may use the same in such a manner as not

to affect the exercise of the easement," Article

635 thereof is specific in saying that "all matters

concerning easements established for public or

communal use shall be governed by the special

laws and regulations relating thereto, and, in the

absence thereof, by the provisions of this Title

Title VII on Easements or Servitudes."

Furthermore, according to DENR A.O. No. 99-21,

When

titled

lands

are

subdivided

or

consolidated-subdivided into lots for residential,

commercial

or

industrial

purposes

the

segregation of the three (3) meter wide strip

along the banks of rivers or streams shall be

observed and be made part of the open space

requirement pursuant to P.D. 1216. The strip

shall be preserved and shall not be subject to

subsequent subdivision. Certainly, in the case of

residential subdivisions, the allocation of the 3meter strip along the banks of a stream, like the

Mahabang Ilog Creek in this case, is required and

shall be considered as forming part of the open

space requirement pursuant to P.D. 1216 dated

October 14, 1977. Said law is explicit: open

spaces are "for public use and are, therefore,

PROPERTY CASES | Digested by Terence Valdehueza And Mia Unabia

beyond the commerce of men" and that "[the]

areas reserved for parks, playgrounds and

recreational use shall be non-alienable public

lands, and non-buildable."

expenses, and costs be awarded in their favor;

and finally, that injunctive relief be issued

against respondent to prevent it from selling the

subject property.

The Court, however, cannot agree with the trial

court's opinion, as to which the CA did not pass

upon, that respondents have a better right to

possess the subject portion of the land because

they are occupying an area reserved for public

easement purposes. Similar to petitioner,

respondents have no right or title over it

precisely because it is public land. Likewise, we

repeatedly held that squatters have no

possessory rights over the land intruded upon.

The length of time that they may have physically

occupied the land is immaterial; they are

deemed to have entered the same in bad faith,

such that the nature of their possession is

presumed to have retained the same character

throughout their occupancy.

In its Answer with Special Affirmative Defenses

and Counterclaim, respondent claimed that

petitioners have no cause of action; that TCT No.

T- 63184 is a valid and subsisting title; that the

case for quieting of title constitutes a collateral

attack upon TCT No. T-63184; and that

petitioners have no title to the subject property

and are mere illegal occupants thereof. Thus, it

prayed for the dismissal of Civil Case No. 4946-R

and an award of exemplary damages, attorneys

fees, litigation expenses, and costs in its favor.

RESIDENTS

OF

LOWER

ATAB

AND

TEACHERS' VILLAGE, STO. TIMAS PROPER

BARANGAY, BAGUIO CITY, REPRESENTED BY

PULAS, LAPAO, ET AL, Petitioners, v. STA.

MONICA INDUSTRIAL AND DEVELOPMENT

CORP., Respondent.

G.R. No. 198878

October 15, 2014

FACTS: In May 2001, petitioners residents of

Lower Atab & Teachers Village, Sto. Tomas

Proper Barangay, Baguio City filed a civil case

for quieting of title with damages against

respondent

Sta.

Monica

Industrial

and

Development Corporation. The case was

docketed as Civil Case No. 4946-R and assigned

to Branch 59 of the Baguio RTC. The Complaint in

said case essentially alleged that petitioners are

successors and transferees-in-interest of Torres,

the supposed owner of an unregistered parcel of

land in Baguio City (the subject property,

consisting of 177,778 square meters) which

Torres possessed and declared for tax purposes

in 1918; that they are in possession of the

subject property in the concept of owner,

declared their respective lots and homes for tax

purposes, and paid the real estate taxes thereon;

that in May 2000, respondent began to erect a

fence on the subject property, claiming that it is

the owner of a large portion thereof by virtue of

Transfer Certificate of Title No. T-63184 (TCT No.

T-63184); that said TCT No. T-63184 is null and

void, as it was derived from Original Certificate

of Title No. O-281 (OCT No. O-281), which was

declared void pursuant to Presidential Decree No.

1271 (PD 1271) and in the decided case of

Republic v. Marcos; and that TCT No. T-63184 is a

cloud upon their title and interests and should

therefore be cancelled. Petitioners thus prayed

that respondents TCT No. T-63184

be

surrendered and cancelled; that actual, moral

and exemplary damages, attorneys fees, legal

ISSUES: Petitioners raise the following issues in

this Petition:

1. The Trial Court and the Court of Appeals erred

in finding that the Petitioners x x x have no

cause of action.

2. The Trial Court and the Court of Appeals erred

in finding that the action is a collateral attack on

the Torrens Title of respondent Corporation.

3. The Trial Court and the Court of Appeals erred

in finding that the present action is to annul the

title of respondent Corporation due to fraud,

[thus] it should be the Solicitor General who

should file the case for reversion.

4. The Trial Court and the Court of Appeals erred

in finding that the validation of TCT No. T-63184

registered in the name of the respondent

corporation was in accordance with law.

HELD: The Court denies the Petition. For an

action to quiet title to prosper, two indispensable

requisites must be present, namely: "(1) the

plaintiff or complainant has a legal or an

equitable title to or interest in the real property

subject of the action; and (2) the deed, claim,

encumbrance, or proceeding claimed to be

casting cloud on his title must be shown to be in

fact invalid or inoperative despite its prima facie

appearance of validity or legal efficacy."

"Legal title denotes registered ownership, while

equitable title means beneficial ownership."

Beneficial ownership has been defined as

ownership recognized by law and capable of

being enforced in the courts at the suit of the

beneficial

owner.

Blacks

Law

Dictionary

indicates that the term is used in two senses:

first, to indicate the interest of a beneficiary in

trust

property

(also

called

"equitable

ownership"); and second, to refer to the power of

a corporate shareholder to buy or sell the shares,

though the shareholder is not registered in the

corporations books as the owner. Usually,

beneficial ownership is distinguished from naked

ownership, which is the enjoyment of all the

benefits and privileges of ownership, as against

possession of the bare title to property.

PROPERTY CASES | Digested by Terence Valdehueza And Mia Unabia

Petitioners do not have legal or equitable title to

the subject property. Evidently, there are no

certificates of title in their respective names. And

by their own admission in their pleadings,

specifically

in

their

pre-trial

brief

and

memorandum before the trial court, they

acknowledged that they applied for the purchase

of the property from the government, through

town site sales applications coursed through the

DENR. In their Petition before this Court, they

particularly prayed that TCT No. T-63184 be

nullified in order that the said title would not

hinder the approval of their town site sales

applications pending with the DENR. Thus,

petitioners admitted that they are not the

owners of the subject property; the same

constitutes state or government land which they

would like to acquire by purchase. It would have

been different if they were directly claiming the

property as their own as a result of acquisitive

prescription, which would then give them the

requisite equitable title. By stating that they

were in the process of applying to purchase the

subject property from the government, they

admitted that they had no such equitable title, at

the very least, which should allow them to

prosecute a case for quieting of title.

dismissed by the government which could

indicate that the subject property is still available

for distribution to qualified beneficiaries. If TCT

No. T-63184 is indeed null and void, then such

proceeding would only be proper to nullify the

same. It is just that a quieting of title case is not

an option for petitioners, because in order to

maintain such action, it is primarily required that

the plaintiff must have legal or equitable title to

the subject property a condition which they

could not satisfy.

In short, petitioners recognize that legal and

equitable title to the subject property lies in the

State. Thus, as to them, quieting of title is not an

available remedy.

Consequently, petitioner filed a Petition for

Dissolution of Conjugal Partnership dated

December 14, 2000 praying for the distribution

of the following described properties claimed to

have been acquired during the subsistence of

their marriage, to wit:

By Purchase:

a. Lot 1, Block 3 of the consolidated survey of

Lots 2144 & 2147 of the Dumaguete Cadastre,

covered by Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) No.

22846, containing an area of 252 square meters

(sq.m.), including a residential house constructed

thereon.

b. Lot 2142 of the Dumaguete Cadastre, covered

by TCT No. 21974, containing an area of 806

sq.m., including a residential house constructed

thereon.

c. Lot 5845 of the Dumaguete Cadastre, covered

by TCT No. 21306, containing an area of 756

sq.m.

d. Lot 4, Block 4 of the consolidated survey of

Lots 2144 & 2147 of the Dumaguete Cadastre,

covered by TCT No. 21307, containing an area of

45 sq.m.

Lands within the Baguio Townsite Reservation are

public land. Laws and decrees such as PD 1271

were passed recognizing ownership acquired by

individuals over portions of the Baguio Townsite

Reservation, but evidently, those who do not fall

within the coverage of said laws and decrees

the petitioners included cannot claim

ownership over property falling within the said

reservation. This explains why they have

pending applications to purchase the portions of

the subject property which they occupy; they

have no legal or equitable claim to the same,

unless ownership by acquisitive prescription is

specifically authorized with respect to such

lands, in which case they may prove their

adverse possession, if so. As far as this case is

concerned, the extent of petitioners possession

has not been sufficiently shown, and by their

application to purchase the subject property, it

appears that they are not claiming the same

through acquisitive prescription.

The trial and appellate courts are correct in

dismissing Civil Case No. 4946-R; however, they

failed to appreciate petitioners admission of lack

of equitable title which denies them the standing

to institute a case for quieting of title.

Nevertheless, they are not precluded from filing

another case a direct proceeding to question

respondents TCT No. T-63184; after all, it

appears that their townsite sales applications are

still pending and have not been summarily

With the conclusion arrived at, the Court finds no

need to resolve the other issues raised.

WILLIAM BEUMER, Petitioner, vs. AVELINA

AMORES, Respondent.

G.R. No. 195670

December 3, 2012

FACTS: Petitioner, a Dutch National, and

respondent, a Filipina, married in March 29,

1980. After several years, the RTC of Negros

Oriental, Branch 32, declared the nullity of their

marriage in the Decision dated November 10,

2000 on the basis of the formers psychological

incapacity as contemplated in Article 36 of the

Family Code.

By way of inheritance:

e. 1/7 of Lot 2055-A of the Dumaguete Cadastre,

covered by TCT No. 23567, containing an area of

2,635 sq.m. (the area that appertains to the

conjugal partnership is 376.45 sq.m.).

f. 1/15 of Lot 2055-I of the Dumaguete Cadastre,

covered by TCT No. 23575, containing an area of

360 sq.m. (the area that appertains to the

conjugal partnership is 24 sq.m.).

In defense, respondent averred that, with the

exception of their two (2) residential houses on

PROPERTY CASES | Digested by Terence Valdehueza And Mia Unabia

Lots 1 and 2142, she and petitioner did not

acquire any conjugal properties during their

marriage, the truth being that she used her own

personal money to purchase Lots 1, 2142, 5845

and 4 out of her personal funds and Lots 2055-A

and 2055-I by way of inheritance. She submitted

a joint affidavit executed by her and petitioner

attesting to the fact that she purchased Lot 2142

and the improvements thereon using her own

money.

Accordingly, respondent sought the dismissal of

the petition for dissolution as well as payment for

attorneys fees and litigation expenses.

During trial, petitioner testified that while Lots 1,

2142, 5845 and 4 were registered in the name of

respondent, these properties were acquired with

the money he received from the Dutch

government benefit since respondent did not

have sufficient income to pay for their

acquisition. He also claimed that the joint

affidavit they submitted before the Register of

Deeds of Dumaguete City was contrary to Article

89 of the Family Code, hence, invalid.

For her part, respondent maintained that the

money used for the purchase of the lots came

exclusively from her personal funds, in particular,

her earnings from selling jewelry as well as

products from Avon, Triumph and Tupperware.

She further asserted that after she filed for

annulment of their marriage in 1996, petitioner

transferred to their second house and brought

along with him certain personal properties,

consisting of drills, a welding machine, grinders,

clamps, etc. She alleged that these tools and

equipment have a total cost of P500,000.00.

ISSUE: Whether or not Beumer has a right to

assert or claim half or whole of the purchase

price used in the purchase of the real properties

subject of this case.

HELD: Undeniably, petitioner openly admitted

that he is well aware of the constitutional

prohibition and even asseverated that, because

of such prohibition, he and respondent registered

the subject properties in the latters name.

Clearly, petitioners actuations showed his

palpable intent to skirt the constitutional

prohibition. On the basis of such admission, the

Court finds no reason why it should not apply the

Muller ruling and accordingly, deny petitioners

claim for reimbursement.

In this case, petitioners statements regarding

the real source of the funds used to purchase the

subject parcels of land dilute the veracity of his

claims: While admitting to have previously

executed a joint affidavit that respondents

personal funds were used to purchase Lot 1, he

likewise claimed that his personal disability funds

were used to acquire the same. Evidently, these

inconsistencies show his untruthfulness. Thus, as

petitioner has come before the Court with

unclean hands, he is now precluded from seeking

any equitable refuge.

In any event, the Court cannot, even on the

grounds of equity, grant reimbursement to

petitioner given that he acquired no right

whatsoever over the subject properties by virtue

of its unconstitutional purchase. It is wellestablished that equity as a rule will follow the

law and will not permit that to be done indirectly

which, because of public policy, cannot be done

directly. Surely, a contract that violates the

Constitution and the law is null and void, vests

no rights, creates no obligations and produces no

legal effect at all. Corollary thereto, under Article

1412 of the Civil Code, petitioner cannot have

the subject properties deeded to him or allow

him to recover the money he had spent for the

purchase thereof. The law will not aid either

party to an illegal contract or agreement; it

leaves the parties where it finds them. Indeed,

one cannot salvage any rights from an

unconstitutional transaction knowingly entered

into.

FLORENTINO W. LEONG AND ELENA LEONG,

ET

AL., Petitioners, v.

EDNA

C.

SEE, Respondent.

G.R. No. 194077

December 3, 2014

FACTS: The spouses Florentino Leong and

Carmelita Leong used to own the property

located at No. 53941 Z.P. De Guzman Street,

Quiapo, Manila.

Petitioner Elena Leong (Elena) is Florentino's

sister-in-law. She had stayed with her in-laws on

the property rental-free for over two decades

until the building they lived in was razed by fire.

They then constructed makeshift houses, and the

rental-free arrangement continued. Florentino

and Carmelita immigrated to the United States

and eventually had their marriage dissolved in

Illinois. A provision in their marital settlement

agreement states that"Florentino shall convey

and quitclaim all of his right, title and interest in

and to 540 De Guzman Street, Manila,

Philippines . . . to Carmelita."

The Court of Appeals found that "[a]pparently

intercalated in the lower margin of page 12 of

the instrument was a long-hand scribbling of a

proviso,

purporting

to

be

a

footnote

remark":Neither party shall evict or charge rent

to relatives of the parties, or convey title, until it

has been established that Florentino has clear

title to the Malabon property. Clear title to be

PROPERTY CASES | Digested by Terence Valdehueza And Mia Unabia

established by the attorneys for the parties or

the ruling of a court of competent jurisdiction. In

the event Florentino does not obtain clear title,

this court reserves jurisdiction to reapportion the

properties or their values to effect a 50-50

division of the value of the 2 remaining Philippine

properties.

On November 14, 1996, Carmelita sold the land

to Edna. In lieu of Florentino's signature of

conformity in the deed of absolute sale,

Carmelita presented to Edna and her father,

witness Ernesto See, a waiver of interest

notarized on March 11, 1996 in Illinois. In this

waiver, Florentino reiterated his quitclaim over

his right, title, and interest to the land.

Consequently, the lands title, covered by TCT

No. 231105, was transferred to Edna's name.

Edna was aware of the Leong relatives staying in

the makeshift houses on the land. Carmelita

assured her that her nieces and nephews would

move out, but demands to vacate were

unheeded.

On April 1, 1997, Edna filed a complaint for

recovery of possession against Elena and the

other relatives of the Leong ex-spouses.

In response, Elena alleged the titles legal

infirmity for lack of Florentino's conformity to its

sale. She argued that Carmelita's noncompliance

with the proviso in the property agreement

that the Quiapo property "may not be alienated

without Florentino first obtaining a clean title

over the Malabon property" annulled the

transfer to Edna.

On April 23, 1997, Florentino filed a complaint for

declaration of nullity of contract, title, and

damages against Carmelita Leong, Edna C. See,

and the Manila Register of Deeds, alleging that

the sale was without his consent. The two cases

were consolidated.

ISSUE: Whether or not Edna was a purchaser in

good faith.

HELD: First, good faith is presumed, and

petitioners did not substantiate their bold

allegation of fraud. Second, respondent did

notrely on the clean title alone precisely because

of the possession by third parties, thus, she also

relied on Florentinos waiver of interest.

Respondent even verified the authenticity of the

title at the Manila Register of Deeds with her

father and Carmelita. These further inquiries

prove respondents good faith.

By her overt acts, Edna See with her father

verified the authenticity of Carmelitas land title

at the Registry of Deeds of Manila. There was no

annotation on the same thus deemed a clean

title (page 19, TSN, 12 January 2005). Also, she

relied on the duly executed and notarized

Certificate of Authority issued by the State of

Illinois and Certificate of Authentication issued

by the Consul of the Republic of the Philippines

for Illinois in support to the Waiver of Interest

incorporated in the Deed of Absolute Sale

presented to her by Carmelita (Exhibit 2).

Examination of the assailed Certificate of

Authority shows that it is valid and regular on its

face. It contains a notarial seal.

The assailed Certificate of Authority is a

notarized document and therefore, presumed to

be valid and duly executed. Thus, Edna Sees

reliance on the notarial acknowledgment found

in the duly notarized Certificate of Authority

presented by Carmelita is sufficient evidence of

good faith.

PROPERTY CASES | Digested by Terence Valdehueza And Mia Unabia

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Resolution Creating A Constitutional Commission For The Amendment of The Constitution of BukSU-LSGDokument2 SeitenA Resolution Creating A Constitutional Commission For The Amendment of The Constitution of BukSU-LSGTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suggested Answers To 2016 Remedial Law Bar ExamDokument7 SeitenSuggested Answers To 2016 Remedial Law Bar ExamTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oath of Office (Officers' Copy)Dokument12 SeitenOath of Office (Officers' Copy)Terence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 180771Dokument13 SeitenG.R. No. 180771Terence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joseph E. Estrada, Petitioner, vs. Aniano DesiertoDokument14 SeitenJoseph E. Estrada, Petitioner, vs. Aniano DesiertoTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISSUE: Whether The Right To Travel Is Covered by The Rule On The RulingDokument2 SeitenISSUE: Whether The Right To Travel Is Covered by The Rule On The RulingTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bukidnon State University College of Law Law Students' SocietyDokument3 SeitenBukidnon State University College of Law Law Students' SocietyTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cañiza v. Court of Appeals Alamayri v. The PabalesDokument15 SeitenCañiza v. Court of Appeals Alamayri v. The PabalesTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Liability Arising From DelictDokument21 SeitenCivil Liability Arising From DelictTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 Question # 3, (4%)Dokument3 Seiten2014 Question # 3, (4%)Terence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 Bar Qs - RemedialDokument19 Seiten2014 Bar Qs - RemedialTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angelito Ramiscal and Mercedes Orzame vs. Atty. Edgar S. Orro - Digest and Full CaseDokument4 SeitenAngelito Ramiscal and Mercedes Orzame vs. Atty. Edgar S. Orro - Digest and Full CaseTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Pre-Order SheetDokument16 SeitenBook Pre-Order SheetTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facts:: Vda. de Manalo Vs CA GR No. 129242, January 16, 2001Dokument7 SeitenFacts:: Vda. de Manalo Vs CA GR No. 129242, January 16, 2001Terence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Considerations: Chapter OneDokument1 SeiteGeneral Considerations: Chapter OneTerence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A.M. No. 03-02-05-SCDokument18 SeitenA.M. No. 03-02-05-SCTerence Valdehueza100% (1)

- Compiled Cases (Article 2 To 13)Dokument13 SeitenCompiled Cases (Article 2 To 13)Terence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facts:: Vda. de Manalo Vs CA GR No. 129242, January 16, 2001Dokument4 SeitenFacts:: Vda. de Manalo Vs CA GR No. 129242, January 16, 2001Terence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facts:: Vda. de Manalo Vs CA GR No. 129242, January 16, 2001Dokument5 SeitenFacts:: Vda. de Manalo Vs CA GR No. 129242, January 16, 2001Terence ValdehuezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCL I Letters of CreditDokument4 SeitenSCL I Letters of CreditTerence Valdehueza100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Ponencias of J. Caguioa in CIVIL LAW 2022Dokument343 SeitenPonencias of J. Caguioa in CIVIL LAW 2022Paolo Ollero100% (1)

- Bob-Sms-Karol Bagh-Harvinder Singh Sahni-July-2020Dokument13 SeitenBob-Sms-Karol Bagh-Harvinder Singh Sahni-July-2020ramanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ed 2023 01222859Dokument7 SeitenEd 2023 01222859dangerpavdevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heirs of Sandejas Vs Alex LinaDokument4 SeitenHeirs of Sandejas Vs Alex LinaailynvdsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bonifacio Olegario Vs CADokument1 SeiteBonifacio Olegario Vs CAClase Na Pud100% (1)

- Deed of Sale of Motor VehicleDokument1 SeiteDeed of Sale of Motor Vehiclezatarra_12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Questions Regarding SALES and 2000 JuresprudenceDokument25 SeitenBar Questions Regarding SALES and 2000 JuresprudenceJoel MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conveyance & Deemed Conveyance of Land or PropertyDokument37 SeitenConveyance & Deemed Conveyance of Land or PropertyAnand Bhagat100% (1)

- Roberto Laperal Jr. Et - Al vs. Ramon Katigbak, Et - Al.Dokument9 SeitenRoberto Laperal Jr. Et - Al vs. Ramon Katigbak, Et - Al.Siobhan RobinNoch keine Bewertungen

- LTD Cases Last PartDokument4 SeitenLTD Cases Last PartlexxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mangalore Electricity Supply Company Limited: Transfer of InstallationDokument10 SeitenMangalore Electricity Supply Company Limited: Transfer of InstallationVinZ VNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cagayan Valley Inc., Vs CADokument3 SeitenCagayan Valley Inc., Vs CAI.G. Mingo MulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trust DeedDokument2 SeitenTrust DeedDon Corleone100% (4)

- What Is A Mortgage DeedDokument2 SeitenWhat Is A Mortgage DeedAdan HoodaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Property Case DigestsDokument95 SeitenProperty Case DigestsAyana LockeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contract To Sell-Villa Kieran-FinalizedDokument4 SeitenContract To Sell-Villa Kieran-FinalizedOmnibus MuscNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guerrero Sales ContributionDokument13 SeitenGuerrero Sales ContributionWilfredo Guerrero IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- 4473-4474 OrdersDokument11 Seiten4473-4474 OrdersKUTV 2NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shyam Narayan Prasad Vs Krishna Prasad and OrsDokument8 SeitenShyam Narayan Prasad Vs Krishna Prasad and OrsYeshwanth MCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Africa V Parker and Others 2005Dokument7 SeitenAfrica V Parker and Others 2005Shreya SulaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gibbs Vs Govt of The Philippines, 59 Phil 293 (1933)Dokument16 SeitenGibbs Vs Govt of The Philippines, 59 Phil 293 (1933)Kaye Miranda LaurenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urieta Vda. de Aguilar vs. AlfaroDokument2 SeitenUrieta Vda. de Aguilar vs. AlfarohappypammynessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formaran vs. OngDokument6 SeitenFormaran vs. OngClaudia Rina LapazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition of Common Real Estate TermsDokument20 SeitenDefinition of Common Real Estate TermsloterryjrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Penalosa v. SantosDokument2 SeitenPenalosa v. SantosJennifer OceñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DBP Vs CADokument1 SeiteDBP Vs CAJonnifer QuirosNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 155634 August 16, 2004 REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, Represented by The SOCIAL SECURITY SYSTEM, Petitioner, JERRY V. DAVID, RespondentDokument4 SeitenG.R. No. 155634 August 16, 2004 REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, Represented by The SOCIAL SECURITY SYSTEM, Petitioner, JERRY V. DAVID, RespondentCJ CasedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Tanauan v. MillonteDokument2 SeitenCity of Tanauan v. MillonteJay jogsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Division: Please Take Notice That The Court, Second Division, Issued A Resolution DatedDokument9 SeitenSecond Division: Please Take Notice That The Court, Second Division, Issued A Resolution DatedSalman JohayrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests - Land Titles and Deeds (W5)Dokument7 SeitenCase Digests - Land Titles and Deeds (W5)Bryan Jayson BarcenaNoch keine Bewertungen