Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Tone Problems of To Day

Hochgeladen von

r-c-a-dOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Tone Problems of To Day

Hochgeladen von

r-c-a-dCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Tone-Problems of To-day

Author(s): Alfredo Casella and Theodore Baker

Source: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Apr., 1924), pp. 159-171

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/738265 .

Accessed: 17/02/2015 23:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical

Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

THE MUSICALQUARTERLY

VOL. X

APRIL, 1924

NO. 2

TONE-PROBLEMS OF TO-DAY

THE

By ALFREDO CASELLA

present rapid, deep-reachingevolution of the ancient

diatonic absolutism (of the past) into out-and-out

chromaticism (of the future) has been very diversely

apprehended,according to the diverse mentalityof individuals.

For those who, like the writer,have for years been familiarwith

the mysteries of ultra-moderntechnique, "polytonality" and

"atonality" are now two phases of music not merelyarrived at,

but also, in certain of their aspects, well-nighsuperseded. In

any event, they are fixed historical facts of sufficientmaturity

to furnishplentifulmaterial for careful research. For others,

however, these same problems are nothingmore than fantastic

imaginingsof some fewimpotentmindsavid ofself-advertisement.

Those belongingto this second category we shall leave to

theirown melancholyfate,in so faras they refuseto conceive the

possibilityof evolution,and intrenchthemselveswith desperate

obstinacybehind the ivorytower of theirwillfulblindness. We

shall turn,instead, to those who speak without adequate knowledge, but are reasonable and willingto listento anyone who can

demonstrate,by solid arguments,the correctnessof certainideas.

Polytonality, atonality-these are terms a la mode. But,

among all the personswho employthem daily, veryfewknow,in

reality,preciselywhat theymean. And not seldomone may note

some critic(shakyin matterstheoretical)whoactuallythinksthese

two vocables identicalin meaning.

159

160

The Musical Quarterly

to avoid

Now, a modicumofetymologicalacumenshouldsuffice

this error. "Polytonality"signifies,to be sure,the interpenetration of diversescales; but it likewiseassumes-in the verynature

ofthings-the survivalofthe originalscales (as one mightsay that

graphiccubism is nothingbut theparoxysmof themass-complex).

Contrariwise,"atonality" signifiesthe destructionof the several

diatonic scales (of seven tones), substitutingthereforthe chromatic scale, eithertemperedor Pythagorean.

two totallydifferent

They mean, therefore,

things.

DEFINITIONS:

as understoodto-day,is nothingmorethan moduPolytonality,

lationin simultaneity.

Atonalityis the negationof the diatonicscale and thecommon

chord.-A more abstract definitionof atonality would be, "the

fourthdimensionin music."--And a third (humoristic)definition

wouldbe, "the exceptionmade the rule,or,the death ofthe scale."

Too protracted(and futile) would be the task of recording

(even briefly)how our music,fromits unitonaland exclusivelyconsonantstatusat theRenaissance,has arrivedstepbystepat Tristan.

of passing-notes;then the suspensions;

First of all, the infiltration

afterthem,the appoggiaturas;-the advent of modulation,beginningtimidlyand rarely,growingmoreand morebold and frequent;

the "chromatization"of the passing-notes(the originof the "harmonicalterations");the suppression(1) ofthepreparationof dissonant chords,and (2) of theirresolution;all this is well known,and

constitutesthat long evolutionin whose course the antique consonant music of the fifteenth

centuryhas been graduallydirected

toward the prismatichorizonof chromaticism.

However-in so far as we may assume the solid historical

cultureof the reader-it willnot be superfluousto note the significance ofsome fewphenomenaembracedin the aforesaidevolution.

Amongthese,one of the mostimportant(and too littleinvestigated) is that of the modal contrastbetweenthe ascendingminor

scale:

i~IWO

Tone-Problemsof To-day

161

and the descendingHypodoricscale of the Greeks:

The contrapuntalemploymentof melismata based on these two

scales indubitablyconstitutesthe firsthistoricalexample of the

ofscales and, consequently,ofpolytonality,and it was

simultaneity

the originof singularlybold harmoniceffects:'

a

(Orazio Vecchi)

(J.S. Bach)

4(MozartC

(Beethoven)

1Speaking of the origins of polytonality, we ought to quote, as an example

of simultaneity suggested by a humoristic intent, the end of Mozart's exquisite

Dorfmusikanten-Serenade:

V 6,

,.

.-

for it contains (at the conclusion of the comic "cadenza" of the violin solo which

terminates the Adagio) perhaps the firsthistorical instance of the whole-tone scale

(scala esafonica):

B,9a.

----'----'-":-~

162

The Musical Quarterly

And lying at the root of the above, a classical melodic appoggiatura:

originatedone of the most fruitfulchordsin music,namely:

a chord with whichDebussy, Ravel, Stravinskyand many others

have succeeded in workingwonders.

To companionthisalreadyremotephenomenonprecursoryto

polytonalitythereis anotherhighlyinstructiveone, a forerunner

of modernatonality-that of the "dramatic" employmentof the

diminished seventh-chord.

Domenico Alaleona sympathetically

definesthis quadrad as "the chordof astonishment";and, in fact,

it possessed a mightyquality of melodramaticenergy for our

ancestors. We know that this chord, without being properly

"atonal," none the less representedin its time the most indefinite

harmonic artificeas regards tonal significance,because it may

minor

to six,seven,or even eightdifferent

belong,enharmonically,

scales. Hence it was favoredbetween1750 and 1850 to illustrate

the most despairfuland gloomy theatricalsituations. It would

be hard to say how many deceptions,surprises,oaths and perjurations, assassinations, matrimonial mishaps, tempests, capital

punishmentsand violent deaths of every sort, etc., etc., found

natural expressionin this famouschordforover a century-until

Wagner supplantedit by the seventh-chord

therewithputtingan end to the age of "astonishment."

At all events,it is interestingto note how (forexceptionally

violent situations) the melodramaticcomposers of that period

feltan imperiousdemandfora formofmusicalexpressionreaching

out beyond pure diatonicism,and thereforehad recourse to a

harmonythat was theleasttonalof any knownto them.

Before grapplingwith present-dayproblems,we shall define

Richard Wagneras the final,supremegiant of classic diatonicism.

Tone-Problems of To-day

163

Heir general to the vast tonal apparatus, his genius enriched

diatonic harmonywith resourcesunknownbefore. And marvellously did they interprethis barbaric, forcefulsensuality,these

refinedchromaticalterationsthat invest Tristanwith its

infinitely

morbid,terribleeroticism.

But extremechromaticismis not shownforthby this admirable score. As a matterof fact,the atonal chromaticismofto-day

does not appear in it. The music of Tristanis the uttermostsynthesis, indeed, of chromaticized diatonicism,but its harmonic

substructurerests throughoutand invariably on the major and

minormodes and the threegrandfundamental"functions"-tonic,

dominant,and subdominant.

It is clear that whenthe diatonicsystemhad once attained to

Wagnerian magnificence,nothing was left for the successors of

the Master but to plan their escape, at any cost, fromthe now

exhaustedbinomialmajor-minor,

and to seek new ways of musical

utterance.

Then came Debussy-and a miracle took place. The old

dogmatic fortress,that had successfullyresisted the assaults of

ages and Wagner's tremendousoffensiveas well, crumbledin a

twinkling,as at the touch of a magic wand. And, in its place,

Nature at last arose, resplendentand unfettered. The antique

restrictionof the scales to threein numberbeingfinallyabolished,

the music of Debussy set forthto exploit,with adolescent eagerand Far-Eastern

ness,the resourcesofthe Greek,oriental,whole-tone

scales, neglectedforcenturies.

It is of record,however,that certain Russians had already

pointed out the path forthe youngFrenchmanto follow. Inheritors of the vast treasures, plastic and musical, of fabulous

Byzantium, these men had a premonition-an intuitioncaught

fromtheir ancestral Gregorianvocalization-of the freemusic of

the future. For this reason,our debt of gratitudeto themcannot

be lightlyestimated. It may well be that we actually owe the

salvation of music to theirwork.

Having arrived,withDebussy, at polymodalityin successivity,

and thepossibilitiesfornewtone-combinations

beingthusinfinitely

extended,it was logical that the next generationshould thinkof

introducingthe recent acquisitions in simultaneity. And so it

came, between 1910 and 1914, that our "polytonality" was

born.

164

The Musical Quarterly

As stated above, there are still many who wronglyconsider

polytonalityto be somethingpurely arbitrary,the monstrous

birthof a fewdegenerateminds. They ought,on the contrary,to

in simultaneityofdiatonicfragments

considerthattheintroduction

until then employedonly in successionby means of modulatory

artifice,was bound to come sooneror lateras the resultofthisvery

abuse of modulation. Moreover, the nineteenthcentury (and

even a part of the eighteenth)abounds in polytonalchordsformed

by suspensionsor appoggiaturasand containingmost vital germs

of polytonality:

(Mendelssohn)

The firstworkpresentingpolytonalityin typicalcompleteness

-not merelyin the guise of a more or less happy "experiment,"

but responding throughoutto the demands of expression-is

beyond all question the grandioseLe Sacre du Printempsof Stramimicdramathe tonal supervinsky(1913). In thisextraordinary

the

the

assume

of a new and necesaspect,

positions

significance,

the

for

the

which

evokes

sary language

poet

ingenuous,dolorous

of

the

In

Slavic

soul.

prehistoric

primitivity

my opinion, the

influenceofthiscompositionhas been ofcapital importanceduring

the last decade. It is no exaggerationto comparethis audacious

music to a dazzling beacon which,kindledbut yesterday,dispels

the gloom on the path of our youngmusiciansof the future.

Afterthe appearance of the Sacre du Printemps,polytonality

became a thingof currentusage among the majorityof European

musicians belongingto the "vanguard." And to-day it is no

longer in point to discuss whether the new phenomenonhas

wroughtgood or evil; it appears to us as a fait accompliof such

importthat it is a natural necessity-foranyone who is reallyin

earnest-to studyrationallythe aforesaidphenomenon. We shall

have to wait a long time,though,beforesuch a course of studyis

added to the curriculumof our harmony-schools.

Polytonality,properlyso called, subdividesinto two species,

harmonicand melodic.

Tone-Problems of To-day

165

The harmonic species' is that which superposes and interweaves chordsbelongingto diversetonalities;e.g.:

F?major

$1

ol.maj.

P Mai.

FImaj,'

(B.Bartdk)

(Casella)

(I. Stravinsky)

In certain cases one can speak confidentlyof an "harmonic

counterpoint":

(fromthe Elegia Eroica,191s)

In such a collocationof ideas one mightdefinepolytonalityas

"a representationof harmony." Indeed, it is evident that, with

'Among the most curious of polytonal harmonies we should mention the synthetic major-minorchord, tried several times by Stravinsky,the writer,and others:

.An

(fromthe"Sacredu Printemps"

1913)

(fromthe"Notte di Maggio" 1913)

(4)

.u

.-)

A..

And-marvel of marvels!-we already findsimilar formsin Monteverdi's Orfeo:

A

--AVL

O-ELM6

166

The Musical Quarterly

regardto the greaterpart of modernchords,it is always possible

to attributeto them-with the assistance of God, Padre Mattei,

and a fairamountofgood will-a scholasticinterpretation. E.g.,

in the chord

we may easily conceive the fourhighertones as so many appoggiaturasdestinedto resolveinto

but how much simpler to divide the entire harmonyinto two

chords, the tonic triad of E major and the dominant seventhchordof G-sharp,whollyrejectingthe idea of resolution!

I once comparedthe Odysseyof the Dissonance, "enchained"

frombirthand gainingfreedomlittleby little,to the peregrinations

of some delinquentbetweentwo policemen,Preparationand Resolution, of whose undesirableattentionshe gradually succeeds in

freeinghimself. Such was the careerof the appoggiatura. Originally it was a suspension straitly confined between our two

policemen;then,Preparationbeinggot rid of,it became a real appoggiatura. As time went on, Resolution was also set aside, and

now this same note that was formerlycalled "foreignto the harmony"-atrophied as a resolvable entity-obviously requires

revaluationaccordingto new criticalstandards.

Hence, harmonic polytonality,besides revealing new and

limitless horizons of tone-combinationto the composer,constimeans ofanalysis,throughthe aid of which

tutes a mostefficacious

nevertheone obtains a clear insightinto modernchord-building,

less always conservingthe idea of the diatonic scale, the natural

and indispensablebasis of the polytonalconception.

Melodic polytonalityis that which superposes two or more

melodiesofdiversetonality. It was bornon that day whencanons

fromthe classic canon "at the octave" were admitted;

differing

that is, canons at the second,at the third,at the fourth,etc. Scholastic rigorfor centuriesconstrainedthe voices composingthese

contrapuntal forms to live and move within a common tonality;

but, evidently, a change at any time of the "alterations" of one of

167

Tone-Problems of To-day

the parts would sufficeto arriveat our present-daymelodicpolytonality.

However, while harmonicpolytonalityhas shownitselfto be

a musicalagencyofgreatexpressivepower,as wellas an analytical

factorof the highestvalue, we cannot affirmthe same of melodic

polytonality. The systematicsuperpositionof melodiesbelonging

to diverse tonalities has hithertoled to very few convincing

results. The chief paladin of this new counterpointis Darius

Milhaud, but I cannot say withsinceritythat whenI hear, in his

quartets or his symphonies,four,five,or more instrumentsperformingsimultaneouslyas many melodies of an inoffensiveness

quite inadequate to the end proposed-I repeat, that I cannot

conscientiouslyassertthat the resultis agreeableto my ear.

Yet I myself have variously employed melodic polytonal

superpositions. But, in these,the several melodiesacknowledged

the leadershipof one among them,as in the followingexcerpts:

a (fromthe"Pagine di guerra,"1915)

whole-tone scale

chrom.scale

E major

neutraltonality

E minor

b (from"5 Pieces for string quartet" 1920)

EL min. Hypodoric

B maj.

F

OIL

min

.Hypodoric

7

" ]

'.

D min. Hypodoric

,-._ .

"

168

The Musical Quarterly

Still, nothingshould be rejected a priori. And it may easily

come to pass that this same Milhaud-still so young-will

find some day soon (for in him there is no lack of talent) an

expressiveformulathat willconquereven my skepticism. He has

my fraternalgood wishes.

Before taking up atonality we would call attention for a

momentto two interestinghistoricalfacts.

One of these is the whole-tone

scale, the bugbear of harmonyteacherstwelve or fifteenyears ago. This scale was adopted for

the firsttimeby Liszt in the SursumCordato be foundin Book III

of his Annies de Pelerinage. Anotherexperimentis known (of

nearlythe same epoch, I believe) in Dargomijsky's Stone Guest.

But it was Debussy who has made the mostofthe new scale. His

marvelloussensibilitytaughthim its use to serve his ends. And,

in so doing,he exhaustedits-sooth to say-very limitedpossibilities. So that those who, coming afterhim, continuein an obstinate abuse of "esafonism,"will lose theirtime in the writingof

futilemusic. The whole-tonescale was thoughtby many (some

years since) to be the key to modernmusic. And how oftenhave

I feltobliged to warn our Italian youth against the perilsof this

system,whichlimitsto six the tones of the scale,

poverty-stricken

and the chordsto one only!

The second historicalfact (which is deservingof far more

extendedtreatment,and whichI mustcontentmyselfto-day with

on the

barely mentioning)is the influenceof the piano-keyboard

evolutionof harmony. Let us hope that a thorough-going

treatise

may speedilyappear to illuminatethis neglectedfieldof research.

-Here I can only call attentionto the quantityof combinations

suggestedby the natural polytonality

resultingfromthe mingling

of whitekeys(major scale) and blackkeys(Chinese scale).

Below, for example, is a genial "find" which would hardly

have occurredto its authorhad the keys been otherwisearranged.

(from Petrouchka. I. Stravinsky)

u .

e"

,l

~i, .-

.1

e--

Tone-Problems of To-day

169

Atonalityrepresents,in contrastto polytonality,the second,

and indubitably the most venturesome, of post-Debussyan

problems.

This is a favorableopportunityonce more to pay homage to

the propheticgenius of Liszt, who wrote,as early as 1847, this

surprisingatonal fragment:

(fromthe"FaustSymphonie")

Whereas polytonalityoriginatedin what we may term an

of diatonicism,1and implies in its very being an

intensification

absolute faith in the seven-tone scale and the common chord,

atonalityis rootedin the chromaticscale and, consequently,is the

negationof the consonanttriad.

For these reasons,atonality evades all analysis based on the

ancient diatonic methods:

(A. Sch6nberg,"Erwartung")

.

6 I U

II-----..

An analogy is frequentlyfoundbetweenpolytonaland atonal

chords. But these two species of music conserve fundamental

characteristicswhich cannot be confounded. He who ignores

them,may confoundthem-as one unfamiliarwiththe languages

mightconfoundChinese and Japanese. But this mistake is impossible for an expert in modern problems. In fact, in atonal

music one not seldom meets with chords belongingto traditional

harmony. But their neighborlyrelations to the other chords

deprive the student of any inclinationto reattributeto them the

propertieswhich they enjoyed or the obligationsto which they

weresubjected in the diatonic system.

1I again insist on the close analogy existing between polytonality (simultaneity

interpenetratedby diatonicism) and cubism (simultaneity interpenetratedby masses,

volumes).

170

The Musical Quarterly

It is not easy to determinewhichnatural chord assumes the

functionof fundamentalin atonalityand thus servesas a pendant

to the functionofthe commonchordin diatonicism. But it might

not be impossible-at least provisionally-to recognize the ensemble of the twelve chromatic tones-perhaps as arranged

accordingto an harmonicordersui generissuch as I attemptedas

early as 1913 in my Nottedi Maggio:

-as the natural harmonyof the atonal system,and then to consider any chord of fromthreeto twelve tones as a fragmentor a

permutationof the basic chord.

As a matterof fact,atonalityappears to be the creationof a

ratherthan of a group. He was

single artist,ArnoldSchtinberg,

the firstto cut definitivelyall ties with the idea of tonality.

And since that day, already farbehindus (the threeKlavierstiicke

Op. 11, in whichthe great "transition"was accomplished,date at

least twelve years back, and possibly longer), this man has not

wearied in pursuing the same path, and, heroicallycontending

and even actual

ofhis contemporaries

againstthe incomprehension

destitution,has constructed a musical edifice that represents

to-day one of the grandest creative effortsin musical history.

Works like Pierrotlunaire or the five Orchesterstiicke

may, as the

but

or

case may be, arouse enthusiasm irritation;

they are creas

dismissed

more or less

be

ations which,unquestionably,cannot

of

a

with

novel

tone-technics,but

system

happy experiments

rather demand recognitionas marvellousexpressionsof modern

sensibility,whose musical speech,in its wondrousperfection,may

be comparedonly withthat of a Bach, a Mozart, or a Chopin.

Someone once likened the abolition of tonality to the suppression of private propertyby the bolsheviki. But this witty

paradox does not hold good, forpossessionin private undoubtedly

goes back to the family of Adam, whereas our tonal sense is a

growth of only a few centuries.

Tone-Problems of To-day

171

All the same, I franklyadmit-while admiringSchtinberg's

greatnessand fullyappreciatingthe vast scope of his conquestmy continuingbelief in the possibilitiesof newer musical utterances whichwillmake greateraccount oftraditionalusage. I confess that this total repudiation-however genial in form-of a

past age to which we owe so much, disquiets me in a measure.

And I thinkit probablethat Schtinbergwillremainforfuturetimes

a magnificent,isolated star, and that his imitatorswill, in their

turn,share the fate of Debussy's, Wagner's,or Rossini's.

Furthermore,I fail to perceivehow "Sch*nbergism"can ever

be adapted to the Italian temperament.

To sum up : We have, in the above, recognizedthe perfect

legitimacyof the two grand evolutionaryphenomena at present

controllingour art. We have established their deep-seated and

essential divergence-a divergence,however, which does not at

all exclude a frequentcotiperationbetween the two systemsfor

the creation of new formsof expression. And we hope-despite

the necessary brevity of this essay-that we have sufficiently

demonstratedthe baselessnessof the accusation so oftenbrought

against both tendencies,of arbitrarinessand willfulsystematization. Neither polytonalitynor atonalityis an arbitrarysystem;

the one is a sonorous enhancementresultant fromdiatonic history; while the otheris, perchance,the dawn of a new music-at

all events the conceptionof a mind of exceptionalpotency.

The futurewill sooner or later pronounceits verdict,and will

be in a commandingposition to divide the few actual genuine

creators (for whom these recenttechnical resourceswere nothing

morethan simple,indispensableagenciesforthe attainmentofnew

formsof Beauty) fromthe innumerablefalse revolutionaries,the

clumsy and disingenuousadopters of the selfsameresources,but

merelyforthe sake of an immediateand ephemeralcelebrity.

(Translated by TheodoreBaker.)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Heptatonic Synthetic Scales Nomenclature and Their Teaching in Jazz TheoryDokument20 SeitenHeptatonic Synthetic Scales Nomenclature and Their Teaching in Jazz Theoryr-c-a-d100% (1)

- 2013 PDFDokument132 Seiten2013 PDFr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Advanced Modal Jazz Harmony Applied To Twentieth Century Music Compositional Techniques in Jazz StyleDokument199 SeitenAdvanced Modal Jazz Harmony Applied To Twentieth Century Music Compositional Techniques in Jazz Styler-c-a-d100% (1)

- Polymodality, Counterpoint, and Heptatonic Synthetic Scales in Jazz CompositionDokument198 SeitenPolymodality, Counterpoint, and Heptatonic Synthetic Scales in Jazz Compositionr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Nothing But 'Nett: August 2013 Digital EditionDokument58 SeitenNothing But 'Nett: August 2013 Digital Editionr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Road Royalty: Diana Krall'sDokument132 SeitenRoad Royalty: Diana Krall'sr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Medeski Flies Solo: MAY 2013 Digital EditionDokument56 SeitenMedeski Flies Solo: MAY 2013 Digital Editionr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFDokument140 SeitenJazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

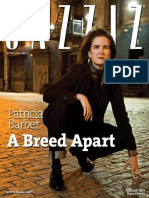

- Patricia Barber: A Breed ApartDokument44 SeitenPatricia Barber: A Breed Apartr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music Group Assessment RubricDokument1 SeiteMusic Group Assessment Rubricr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Editorial: Roger Fagge and Nicholas GebhardtDokument278 SeitenEditorial: Roger Fagge and Nicholas Gebhardtr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jazz & Culture Vol. 1, 2018 PDFDokument149 SeitenJazz & Culture Vol. 1, 2018 PDFr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFDokument140 SeitenJazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- JINY Nov10 webFINAL PDFDokument68 SeitenJINY Nov10 webFINAL PDFr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natalie Wren CornwallDokument8 SeitenNatalie Wren Cornwallr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alexander Rosenblatts Piano Sonata No2 and Its Influences The Blending of Classical Techniques and Jazz ElementsDokument85 SeitenAlexander Rosenblatts Piano Sonata No2 and Its Influences The Blending of Classical Techniques and Jazz Elementsr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Creation of A Model To Predict Jazz Improvisation AchievementDokument145 SeitenThe Creation of A Model To Predict Jazz Improvisation Achievementr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Bemsha SwingDokument27 SeitenBemsha Swingr-c-a-d100% (2)

- Research Journal (January 2007) : Guidelines For Submitting Articles For Publication in JazzDokument4 SeitenResearch Journal (January 2007) : Guidelines For Submitting Articles For Publication in Jazzr-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Patitucci: Jazz Education Sourcebook & Program GuideDokument84 SeitenJohn Patitucci: Jazz Education Sourcebook & Program Guider-c-a-dNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Taxation One Complete Updated (Atty. Mickey Ingles)Dokument116 SeitenTaxation One Complete Updated (Atty. Mickey Ingles)Patty Salas - Padua100% (11)

- Engineering Discourse Communities RMDokument4 SeitenEngineering Discourse Communities RMapi-336463296Noch keine Bewertungen

- Deferred Tax QsDokument4 SeitenDeferred Tax QsDaood AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- NMC CBT Sample Q&a Part 3 AcDokument14 SeitenNMC CBT Sample Q&a Part 3 AcJoane FranciscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content Kartilya NG Katipunan: Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan NG Mga Anak NG Bayan)Dokument6 SeitenContent Kartilya NG Katipunan: Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan NG Mga Anak NG Bayan)AngelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admission Sos 2013-14090513 PDFDokument21 SeitenAdmission Sos 2013-14090513 PDFmanoj31285manojNoch keine Bewertungen

- Math Studies Financial MathsDokument7 SeitenMath Studies Financial MathsGirish MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tutorial 2 - Financial EnvironmentDokument5 SeitenTutorial 2 - Financial EnvironmentShi ManNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report End of Chapter 1Dokument4 SeitenReport End of Chapter 1Amellia MaizanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Do Climates Change ?: Climate Changes Over The Last MillenniumDokument44 SeitenWhy Do Climates Change ?: Climate Changes Over The Last Millenniumshaira alliah de castroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crim 2 Module 2 Atty A.D.G.Dokument7 SeitenCrim 2 Module 2 Atty A.D.G.Badens DgNoch keine Bewertungen

- US of GIT of CattleDokument13 SeitenUS of GIT of CattlesangeetsamratNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internship Proposal FormDokument3 SeitenInternship Proposal FormMuhammad FidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Optical CamouflageDokument27 SeitenOptical CamouflageAlliluddin ShaikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Title Toolbox 1 ADokument2 SeitenTitle Toolbox 1 AGet LiveHelpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Perspectives Reflective PaperDokument3 SeitenGlobal Perspectives Reflective PaperMoaiz AttiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acd 1Dokument3 SeitenAcd 1Kath LeynesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answers & Solutions: For For For For For JEE (MAIN) - 2019 (Online) Phase-2Dokument22 SeitenAnswers & Solutions: For For For For For JEE (MAIN) - 2019 (Online) Phase-2Manila NandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Price and Output Determination Under OligopolyDokument26 SeitenPrice and Output Determination Under OligopolySangitha Nadar100% (1)

- WearebecausewebelongDokument3 SeitenWearebecausewebelongapi-269453634Noch keine Bewertungen

- Digital Dash I/O Adapter Configuration: Connector Pin FunctionsDokument8 SeitenDigital Dash I/O Adapter Configuration: Connector Pin FunctionsAfeef Ibn AlbraNoch keine Bewertungen

- English For AB SeamenDokument96 SeitenEnglish For AB SeamenLiliyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Architecture As Interface - Healing Architecture For Epatients. In: Healing Architecture. Hrsg. Nickl-Weller. 2013Dokument6 SeitenArchitecture As Interface - Healing Architecture For Epatients. In: Healing Architecture. Hrsg. Nickl-Weller. 2013Asmaa AyadNoch keine Bewertungen

- E5170s-22 LTE CPE - Quick Start Guide - 01 - English - ErP - C - LDokument24 SeitenE5170s-22 LTE CPE - Quick Start Guide - 01 - English - ErP - C - LNelsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Personal Brand and Career GoalsDokument3 SeitenMy Personal Brand and Career GoalsPhúc ĐàoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lubi Dewatering PumpDokument28 SeitenLubi Dewatering PumpSohanlal ChouhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- E9d30c8 4837smartDokument1 SeiteE9d30c8 4837smartSantoshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alcatel 9400 PDFDokument4 SeitenAlcatel 9400 PDFNdambuki DicksonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Appropriate Biochemical Oxygen Demand Concentration For Designing Domestic Wastewater Treatment PlantDokument8 SeitenThe Appropriate Biochemical Oxygen Demand Concentration For Designing Domestic Wastewater Treatment PlantabdulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arizona History and Social Science StandardsDokument57 SeitenArizona History and Social Science StandardsKJZZ PhoenixNoch keine Bewertungen