Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Using The Jigsaw Classroom, by Peter Hastie and Ashley Casey

Hochgeladen von

Pablo BarreiroOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Using The Jigsaw Classroom, by Peter Hastie and Ashley Casey

Hochgeladen von

Pablo BarreiroCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Practice Matters

Using the

to Facilitate Student-Designed Games

Peter Hastie and Ashley Casey

ccording to the Qualifications and

Curriculum Development Authority

(QCDA). the new secondary curriculum

in physical education focuses on developing

the skills and qualities that learners need to

succeed in school and the broader

community. Underpinning this curriculum are

personal. learning and thinking skills (PLTS)

that are considered essential to successful

engagement in the subject matter.

Achievement of these PLTS should see

students as independent enquirers. creative

thinkers. team workers. self-managers.

effective participators. and reflective learners.

In order to achieve these goals. students are

expected to be presented with learning

experiences that allow them to "work with

increasing independence. applying their

competence and creativity to different types

of activity". "experiment confidently with their

own creative approaches to produce effective

outcomes". collaborate with others in working

towards a common goal". "take personal

responsibility for organising their time and

resources". "engage with activities that they

enjoy and have selected for themselves", and

"identify for themselves new and improved

techniques. tactics and strategies:'

A case for student-designed

games

It is the intent of this paper to present the

idea of "student- designed games" as a highly

appropriate. but also stimulating and

beneficial method for teachers in Key Stages

3 and 4 to engage students in these PLTS. In

Physical Education

Matters

Spring

2010

addition. we present a technique that

teachers can use to help structure students'

first experiences with games making that

allow them to be successful.

In games making. students design their

own games within certain parameters

presented by the teacher. From a

constructivist perspective. Rovegno

and Bandhauer (1994) suggest that

asking students to design their own

games allows them to engage actively

with and explore components of game

play (skills and strategy) and. in turn. to

construct a deeper understanding of

these components. as well as helping

them to think critically about their

experiences playing games and sports at

break and after school.

Games making is not a case where all the

teacher has to do is explain the skill. hand

out equipment. and say. "Make up a game:'

Cox (1988) lists three slants to presenting

games making tasks. and describes them as

the "structured choice." "limited choice." and

"open choice" approaches. At the most basic

level (structured approach) the teacher limits

the number of choices available to the

students. For example. the teacher may limit

the number of players on a game. and limit

the choice of equipment to no more than five

items. Alternately. students can work with

games they already play and make

manipulations to the number of players on a

side. the size of the court/field. the

implements and/or balls used. or some

simple rules. Cox (1988. p. 15) suggests that

the structured approach" prevents the

15

Practice Matters

~

2

development of overcomplicated games

which can (and often do) take an inordinate

time to devise:' In the limited choice and

open choice approaches, students can design

games that are completely unique and

present tactical problems not seen in any of

the sports they historically play.

The jigsaw classroom

As was mentioned earlier, this paper presents

a technique teachers can use when first

introducing games making to students. The

technique is known as the "jigsaw

classroom", and the underlying theory is that

just as in a jigsaw puzzle, each piece - each

student's part - is essential for the

completion and full understanding of the final

product. It is based upon the wider

pedagogical model of cooperative learning

and seeks to achieve five elements for pupil

learning: positive interdependence, individual

accountability, shared group goals, group

processing, and face-to-face interaction. If

each student's part is essential, then each

student is essential; and that is precisely what

makes this strategy so effective. The following

capsule gives an example of how the jigsaw

classroom works.

The students are divided into the

small 'home' groups common to

cooperative learning:

Group A:

Student

Group B:

Student

Group C:

Student

Group 0:

Student

<

<

Student

3A

Student

3B

Student

3C

Student

3D

1A, Student 2A,

1 B, Student 2B,

1C, Student 2C,

10, Student 20,

The students numbered one then form

an 'expert' group and are given a concept

to master. The students with numbers

two and three respectively also form

separate expert groups and undertake to

learn or develop different concepts.

Eventuallythe home groups are reformed

and students try to teach each other the

information they have learnt. The model

is structured so that the only access any

student has to the other concepts is by

learning from the related expert.

I used information of gymnastic ability

and existing friendship groups to choose

the home groups. In the first week of six

the pupils were introduced to the jigsaw

classroom and divided into their home

groups. Once the home groups were

together the students were asked to

choose an expertise (mats, box, bench)

and then the expert groups for the

16

creation of the expert sequences were

created. Thisprocess took two weeks,

at the end of which each expert group

was required to hand in a sequence

prompt sheet. Experts then spent weeks

three, four and five back in their home

groups learning the three sections of the

final routine. Week six was used for

group performances, although some

time was also found for whole sequence

practice.

Casey (2004, p.12)

Using the jigsaw in games

making

All games are comprised of primary rules and

secondary rules. Primary rules are those that

identify how the game is played and how to

win. They provide a game's essential

character and what distinguishes it from

another. A primary rule of volleyball is that

you must volley the ball with your hands (i.e.,

you cannot catch or throw it), while in

football, players can only use their feet and

head to transfer the ball while inside the field

of play (they can throw it in from the

sideline). These rules make volleyball

different from badminton, and football

different from handball where you can throw

the ball into the goal. Primary rules also

designate players' rights from both an

offensive and defensive standpoint. While in

handball, you can take three steps with the

ball, in games like netball and Ultimate Frisbee

you cannot move at all. In basketball you can

only move with the ball while dribbling. In

rugby you can pick up the ball and run with it,

but you are limited to only passing

backwards.

Secondary rules are those that arise out of

the experience of playing a game, and are

those rules that can be changed without

affecting the essential character of the game.

For example, the tiebreak in tennis varies

according to the competition league in which

it is adopted, while the shot clock in

basketball is a secondary rule that limits the

time a team has before it must make a shot

attempt, and differs in every level of

competition. In junior rugby the hand-off and

kick through are removed to allow players to

master the basics of the game before these

elements are employed. while in cricket lost

runs often replace the loss of wickets to

ensure that a batsman gets an equal share of

the bowling.

In a jigsaw lesson students form different

expert teams which meet to design the

primary rules of a particular game. After these

"rules experts" have made their decision.

they then return to their original teams to put

the game together. In this way. all final games

should be the same across groups. If a game

is not developed consistently with the mod

it will be as a result of that particular expert's

lack of understanding or inattention during

the design phase. That student is thereby

accountable to the entire group.

After teams have played the combination

game. they are then able to make teamspecific adjustments to the secondary rules

make it a "good game". By good game we

mean something that is both "playable" and

"enjoyable" for all participants. For example.

game limited to two-footed hopping where

the ball is carried between the knees to se

in a basket will quickly become untenable.

unenjoyable and exhausting to all those

involved. Modifications by a team could

change the methods of progression and

scoring to make the game more competitive

and enjoyable. A team should not feel that

they could win easily but nor should they f

that they have no chance of making an equa

contribution to any of their peers' teams.

Physical Education Matters Spring 201

Practice Matters

Jigsaw examples - Tag games

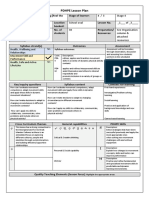

Figure

Students are charged with designing a tag/rig

game. The expert designers in this situation

will determine the rules about:

boundaries and playing area

how to tag (where, equipment, safety)

how to get "unfrozen" after being tagged

safe zones (places where you may not be

tagged)

chasing limitations (how to move, can you

dive after someone to tag them).

Once these rules have been decided upon,

the players return and experiment with the

game. During trials, the rule experts may need

to clarify specific issues again. However, these

meetings should not concern secondary rules.

Once the parent game has been played and

the rules clarified, teams are now able to modify

the game in order to make it a good game.

At Heathcote School (a pseudonym), a group

of ten Year 11 students used this jigsaw

method and created a tag game within 15

minutes. This allowed them to experiment with

each of the more intricate dimensions of the

game to make it more fun and challenging.

Each pupil (see Figure 1) was randomly

allocated to a jigsaw group (1 or 2) and an

expert group (A-B).

The pupils, having noted who would make up

their five-piece jigsaw, joined up with the

expert from the other group and they both

spent five minutes defining their section of the

rules i.e. the A's defined the boundaries and

the playing area, the B's how to tag etc. At the

end of the five minutes the experts returned

to their jigsaw groups and put together the five

pieces of the jigsaw to form the completed tag

game. With the game assembled groups 1 and

2 independently attempted to play the game;

refining the separate elements into a workable

whole. The emphasis was on tinkering rather

than wholesale changes as this would have

been firmly against the student voice the

teacher was trying to encourage.

Once the game had been played and refined

each group had a chance to further modify the

game in line with their aspirations for a better

game. In this way pupils could change or adapt

one or more of the five pieces of the jigsaw tag

game with the aim of creating a better experience

for all involved. The other group then played

this hybrid of the original game and the two

were compared by the ten pupils involved.

Jigsaw Learning is one of a number of

cooperative learning pedagogies that has been

used in physical education to effectively

enhance both academic and social learning

(Casey, Dyson, and Campbell, 2009). Five

distinct and coherent elements personify

cooperative learning:

18

1. Expert

Groups

and Jigsaw

Groups

Expertise

Boundaries and

playing area

How to tag

How to get

"unfrozen" after

being tagged

Safe zones

ca

1A

1B

1C

10

1E

=.bD

2A

2B

2C

2D

2E

Chasing

limitations

en

Positive interdependence

Individual accountability

Promotive (face-to-face) interaction

Group processing

Group goal.

These elements are also interconnected and

they mirror quite closely the skills inherent in

the framework for personal, learning and

thinking skills (PLTS) (Qualifications and

Curriculum Authority (QCA), 2009). In a

Cooperative Learning pedagogy (in this case

Jigsaw) and through game-making the pupils

involved encountered skills from several PLTS

groups. They were challenged to be

independent enquirers (Individual

accountability), creative thinkers (group goal),

reflective learners (group processing), team

workers (promotive interaction) and self

managers (positive interdependence).

Furthermore, we would argue that as part of

the wider context in which this lesson was

taught (a seven week invasion game-making

unit in which the same students created their

own 'open choice" (Cox, 1988) games),

students showed commitment, understanding,

confidence, skills, decision making, a desire to

improve and enjoyment in physical education.

All these areas are outcomes of high quality

physical education and sport (Department for

Education and Skills (DFES)/QCA, 2004) and

were further enhanced by the competitive,

creative and challenge involved in the unit.

This idea is used extensively in Primary

Schools, but a case has yet to be made for its

inclusion in secondary education. Perhaps the

words of classroom teacher best summarise

the outcomes of this unit:

The boys are engaged. All of them.

Even those I would normally struggle to

involve are raring to go. None more so

than the boys who hide away in football

and talk rather than play. I have seen those

boys run away from the ball to ensure they

escape any form of match play yet in this

unit they have been game designers and

trialed games that didn't exist before we

started this unit. The sporting ones loved

it on the whole and while some did moan

a little at the start that they weren't doing

a real game, this soon disappeared as

they got involved in their new games.

The pupils involved in this "teaching experiment'

had previous experience of both gamesmaking and cooperative learning but as the

teacher noted "with such defined limits on

what they could decide upon I believe that any

of my classes, regardless of prior experience,

could have come up with a playable game."

The pupils, as one commented, felt that the

whole process "allowed for the quick

development of a game without a lot of time

being spent in design - which means you can

then work on playing it and modifying it,

which is the most fun part:' To support this

claim, the whole process, including interviews.

changing, set-up and debrief took less than an

hour, making it fit comfortably within a double

lesson in the school's timetable.

References

Casey, A (2004). Piece-by-piece cooperation:

pedagogical change and jigsaw learning, The

British journal of Teaching Physical Education,

34(4), 11-12.

Casey, A, Dyson, B., and Campbell, A (2009).

Action research in physical education:

Focusing beyond myself through cooperative

learning, Educational Action Research, 17(3),

407-423.

Cox, R.L. (1988). Games-making: Principles

and procedures. Scottish journal of Physical

Education, 16, (2), 14-16.

Department for Education and Skills/

Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

(2004). High Quality PE and Sport for Young

People. Annesley, Nottinghamshire:

DfES

Publications.

Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

(2009). A framework of personal, learning

and thinking skills. Accessed from:

http://curriculum.qcda.gov.uk/key-stages

3-and-4/skills/plts/index.aspx

[19/11/09J

Rovegno, I., and Bandhauer, D. (1994). Child

designed games: Experience changes teachers'

conceptions. journal of Physical Education,

Recreation and Dance, 65 (6), 60-63.

Peter Hastie is a Professor

Department

of Kinesiology

Auburn University,

Auburn,

Alabama.

in the

at

Ashley Casey is a Senior Lecturer in

the Faculy of Education and Sport at

University

of Bedfordshire,

Bedford.

Physical

Education

Matters

Spring

2010

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Assignment 2 Task Design - RaftDokument8 SeitenAssignment 2 Task Design - Raftapi-422461005100% (1)

- Coaching Tool Professional Development Planning TemplateDokument1 SeiteCoaching Tool Professional Development Planning Templateapi-362016104Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unit Plan - Pe Throwing and CatchingDokument11 SeitenUnit Plan - Pe Throwing and Catchingapi-296784293100% (2)

- Ist 524-30 Team 4 Case Study 1 Team ResponseDokument6 SeitenIst 524-30 Team 4 Case Study 1 Team Responseapi-562764978Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tiered Lesson Stage 2 PeDokument4 SeitenTiered Lesson Stage 2 Peapi-266333507Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unpacking Standards - Practicum2Dokument30 SeitenUnpacking Standards - Practicum2Flash Royal100% (1)

- Assignment 1 - Unit of Work and Justification Steph LeakeDokument28 SeitenAssignment 1 - Unit of Work and Justification Steph Leakeapi-296358341Noch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Lesson FPD For Soccer Sepep IctDokument6 Seiten3 Lesson FPD For Soccer Sepep Ictapi-443553773Noch keine Bewertungen

- Handball RubricDokument2 SeitenHandball RubricBlaja AroraArwen Alexis100% (1)

- Section 5 Artifact 2 CaptionDokument2 SeitenSection 5 Artifact 2 Captionapi-205202796Noch keine Bewertungen

- Progressive Education In Nepal: The Community Is the CurriculumVon EverandProgressive Education In Nepal: The Community Is the CurriculumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ricky The Rock Lesson PlanDokument4 SeitenRicky The Rock Lesson Planapi-528469698Noch keine Bewertungen

- Observation MathDokument4 SeitenObservation Mathapi-456963900Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pdhpe 7 10 SyllabusDokument67 SeitenPdhpe 7 10 SyllabusPE_NoticeboardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coaching Conversations Using Socratic MethodDokument2 SeitenCoaching Conversations Using Socratic MethodAditya Anand100% (1)

- "Designing & Teaching Learning Goals & Objectives" SummaryDokument10 Seiten"Designing & Teaching Learning Goals & Objectives" SummaryAltamira International School100% (1)

- A New Learning Model On Physical Education: 5E Learning CycleDokument6 SeitenA New Learning Model On Physical Education: 5E Learning CycleAnne Nailul ANoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Teaching Formative Evaluation 1Dokument6 SeitenStudent Teaching Formative Evaluation 1api-252061883Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kindergartenhandbook 14 15Dokument11 SeitenKindergartenhandbook 14 15api-275157078Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2 Raft ProfolioDokument9 SeitenAssignment 2 Raft Profolioapi-297107194Noch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of The Communicative Approach On The Listening and Speaking Skills of Saudi Secondary School Students An Experimental StudyDokument145 SeitenEffect of The Communicative Approach On The Listening and Speaking Skills of Saudi Secondary School Students An Experimental Studymasoha50% (2)

- Stream Selection Criteria in Grade 11 2023-24Dokument2 SeitenStream Selection Criteria in Grade 11 2023-24Ritvik Sarang100% (1)

- Reading Lesson Plan - Dragon Gets byDokument3 SeitenReading Lesson Plan - Dragon Gets byapi-2892327400% (1)

- Pakistan Studies: Course GuideDokument101 SeitenPakistan Studies: Course GuideAliNoch keine Bewertungen

- School Plan 13.6Dokument6 SeitenSchool Plan 13.6Helensburgh Public SchoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- MGMT 373-Personal Effectiveness-Adnan ZahidDokument3 SeitenMGMT 373-Personal Effectiveness-Adnan Zahidsamu samuNoch keine Bewertungen

- TKES Fact Sheets 7-11-2012 PDFDokument101 SeitenTKES Fact Sheets 7-11-2012 PDFjen100% (1)

- Student and Parent Handbook - 2021-2022Dokument58 SeitenStudent and Parent Handbook - 2021-2022ali alhashimiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christ University Course Pack For MAIS CourseDokument71 SeitenChrist University Course Pack For MAIS CourseRohit KishoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Differentiated Learning Theory and Practice April 2018Dokument47 SeitenDifferentiated Learning Theory and Practice April 2018JordanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ArtifactsDokument45 SeitenArtifactsapi-418341355100% (1)

- Edited KSC IIDokument6 SeitenEdited KSC IIapi-299133932Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jump Into Inquiry Without DrowningDokument22 SeitenJump Into Inquiry Without DrowningCeazah Jane Mag-asoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pnaec 875Dokument95 SeitenPnaec 875Rinki Rajesh VattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- OpheaDokument75 SeitenOpheaapi-391714949Noch keine Bewertungen

- EDUC 5440 Unit 7 WADokument5 SeitenEDUC 5440 Unit 7 WAAlex Fung100% (1)

- IGCSE Programme Options Form September 2023Dokument2 SeitenIGCSE Programme Options Form September 2023Noha Mohsen100% (1)

- GR 9 Course Selection Form 2012-13Dokument2 SeitenGR 9 Course Selection Form 2012-13Medford Public Schools and City of Medford, MANoch keine Bewertungen

- Maths FPDDokument2 SeitenMaths FPDapi-280237709Noch keine Bewertungen

- Observationfeedback Ed201Dokument3 SeitenObservationfeedback Ed201api-305785129Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ganag PresentationDokument67 SeitenGanag PresentationPriscilla RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Evaluation FormDokument1 SeiteSelf Evaluation FormEspañola Eloise100% (1)

- Seager B Sped875 m2 Mentor Teacher CollaborationDokument4 SeitenSeager B Sped875 m2 Mentor Teacher Collaborationapi-281775629Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gym - Dog CatcherDokument3 SeitenGym - Dog Catcherapi-267119096Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nep AchievementDokument115 SeitenNep AchievementdswinorganicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Designing A Unit of InstructionDokument21 SeitenDesigning A Unit of Instructioncoleenstanley100% (1)

- Journal of Education PDFDokument3 SeitenJournal of Education PDFpianNoch keine Bewertungen

- InternhandbookDokument43 SeitenInternhandbookMarcial AlingodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 1 Lesson PlansDokument25 SeitenAssignment 1 Lesson Plansapi-369323765Noch keine Bewertungen

- Edu 4203 - Elements of Curriculum DesignDokument4 SeitenEdu 4203 - Elements of Curriculum Designapi-269506025Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Professional Growth Plan 2014Dokument3 SeitenTeacher Professional Growth Plan 2014api-238204144Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yearly Lesson Plan For Year 1Dokument9 SeitenYearly Lesson Plan For Year 1unc_jemzNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020 19 Pakistan Sindh ESPDokument76 Seiten2020 19 Pakistan Sindh ESPSehar TaimoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morfological Components and Functional Characteristics of Elite Soccer Players According To Team PositionDokument1 SeiteMorfological Components and Functional Characteristics of Elite Soccer Players According To Team PositionVibhav SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instructional DesignDokument180 SeitenInstructional DesignBeatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maximizing Student Learning With Flexible GroupingDokument4 SeitenMaximizing Student Learning With Flexible Groupingapi-291864717Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan 4Dokument7 SeitenLesson Plan 4Jeffrey Cantarona AdameNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parent Handbook DMIS 2018-19Dokument36 SeitenParent Handbook DMIS 2018-19Avik KunduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modul Bahasa Inggris 2 - Unit 1 - 7th EditionDokument13 SeitenModul Bahasa Inggris 2 - Unit 1 - 7th EditionAhmad Farrel ZaidanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Year 5daily Lesson Plans Success Criteria Pupils Can 1. Listen and Underline 4 Correct Words. 2. Read and Fill in at Least 6 Blanks CorrectlyDokument8 SeitenYear 5daily Lesson Plans Success Criteria Pupils Can 1. Listen and Underline 4 Correct Words. 2. Read and Fill in at Least 6 Blanks Correctlyjulie ayobNoch keine Bewertungen

- P4C Seminar-495syllabusDokument3 SeitenP4C Seminar-495syllabusVũ Ánh Tuyết Trường THPT ChuyênNoch keine Bewertungen

- PBL Group Presentation Peer Review RubricDokument2 SeitenPBL Group Presentation Peer Review Rubricapi-232022364Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural ComeptenceDokument9 SeitenCultural ComeptenceAnna BellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rozdział 3 Słownictwo Grupa BDokument1 SeiteRozdział 3 Słownictwo Grupa BBartas YTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Education: Learning Activity Sheet For Learning Strand 6 Digital LiteracyDokument2 SeitenDepartment of Education: Learning Activity Sheet For Learning Strand 6 Digital LiteracyMarkee Joyce GalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Procedure 2022-23 (Class-XII)Dokument4 SeitenProject Procedure 2022-23 (Class-XII)Shreya PushkarnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Super Final ThesisDokument31 SeitenSuper Final ThesisGENETH ROSE ULOGNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4.2 Sample InformalProposalDokument4 Seiten4.2 Sample InformalProposalAgbajeola AbiolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Successful Teachers Create A Nurturing Classroom CultureDokument2 SeitenHow Successful Teachers Create A Nurturing Classroom CultureJoana HarvelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report To The Community - KentDokument2 SeitenReport To The Community - KentCFBISDNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effectiveness of Inquiry Teaching in Enhancing Students' Critical ThinkingDokument10 SeitenThe Effectiveness of Inquiry Teaching in Enhancing Students' Critical ThinkingKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Styles SurveyDokument10 SeitenLearning Styles SurveySerenaSanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- RRL Doc1Dokument35 SeitenRRL Doc1Natalie Jane PacificarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inequality ProjectDokument6 SeitenInequality ProjectMilena ZivkovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- IDA DUVNJAK CV BoliaDokument1 SeiteIDA DUVNJAK CV BoliaIdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Determining Textual Evidence-Wps OfficeDokument10 SeitenDetermining Textual Evidence-Wps Officebascoarwin81Noch keine Bewertungen

- D S D F ?: Ifferent Trokes FOR Ifferent OlksDokument5 SeitenD S D F ?: Ifferent Trokes FOR Ifferent Olkssaro kakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume CVDokument1 SeiteResume CVapi-535382697Noch keine Bewertungen

- Prof EdDokument3 SeitenProf EdJason Alejandro Dis-ag IsangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gulbarga University: "Innovation in Banking System"Dokument6 SeitenGulbarga University: "Innovation in Banking System"Veeresh Madival VmNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Literacies 21st Century Position StatementDokument5 SeitenNew Literacies 21st Century Position StatementEdison BuenconsejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budi Waluyo - Personal StatementDokument1 SeiteBudi Waluyo - Personal StatementAndi JenggothNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Educational Resource Centre in Teaching MathematicsDokument17 SeitenRole of Educational Resource Centre in Teaching MathematicsAbisha AbiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compiled RRLsDokument15 SeitenCompiled RRLsJeff Lawrence Lunasco100% (1)

- AY 2021 Sem 2 A309 P11 Instructions For E-LearningDokument7 SeitenAY 2021 Sem 2 A309 P11 Instructions For E-LearningLim Liang XuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mixing ColorsDokument3 SeitenMixing ColorsGeovannie RetiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Should Students Have Part Time JobsDokument1 SeiteShould Students Have Part Time JobsGia BảoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Professional Development in The Use of ICT PDFDokument15 SeitenTeacher Professional Development in The Use of ICT PDFSharif ZulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quarter 1 School Year 2021-2022: Malvar School of Arts and TradeDokument21 SeitenQuarter 1 School Year 2021-2022: Malvar School of Arts and TradeNilo VanguardiaNoch keine Bewertungen