Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Jurnal Risperidone PDF

Hochgeladen von

Chairizal Meiristica YanhaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Jurnal Risperidone PDF

Hochgeladen von

Chairizal Meiristica YanhaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

original article

Long-Acting Risperidone and Oral

Antipsychotics in Unstable Schizophrenia

Robert A. Rosenheck, M.D., John H. Krystal, M.D., Robert Lew, Ph.D.,

Paul G. Barnett, Ph.D., Louis Fiore, M.D., M.P.H., Danielle Valley, M.P.H.,

Soe Soe Thwin, Ph.D., Julia E. Vertrees, Pharm.D.,

and Matthew H. Liang, M.D., M.P.H., for the CSP555 Research Group*

A bs t r ac t

Background

From the Veterans Affairs (VA) New England Mental Illness, Research Education

and Clinical Center, VA Connecticut

Healthcare System, West Haven, and the

Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

(R.A.R., J.H.K.); the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology and Research Information Center VA Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center, Boston (R.L.,

L.F., D.V., S.S.T., M.H.L.); the VA Health

Economics Resource Center, Menlo Park,

CA (P.G.B.); and the VA Cooperative

Studies Program Clinical Research Pharmacy Coordinating Center, Albuquerque,

NM (J.E.V.). Address reprint requests to

Dr. Rosenheck at the VA New England

Mental Illness, Research Education and

Clinical Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System/151D, 950 Campbell Ave.,

West Haven, CT 06516, or at robert

.rosenheck@va.gov.

* The Cooperative Studies Program (CSP)

555 Research Group investigators are

listed in the Supplementary Appendix,

available at NEJM.org.

This article (10.1056/NEJMoa1005987)

was updated on March 7, 2011, at NEJM

.org.

N Engl J Med 2011;364:842-51.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Long-acting injectable risperidone, a second-generation antipsychotic agent, may

improve adherence to treatment and outcomes in schizophrenia, but it has not been

tested in a long-term randomized trial involving patients with unstable disease.

Methods

We randomly assigned patients in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system who had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and who had been hospitalized within the previous 2 years or were at imminent risk for hospitalization to 25 to 50 mg of longacting injectable risperidone every two weeks or to a psychiatrists choice of an oral

antipsychotic. All patients were followed for up to 2 years. The primary end point

was hospitalization in a VA or non-VA psychiatric hospital. Symptoms, quality of life,

and functioning were assessed in blinded videoconference interviews.

Results

Of 369 participants, 40% were hospitalized at randomization, 55% were hospitalized within the previous 2 years, and 5% were at risk for hospitalization. The rate of

hospitalization after randomization was not significantly lower among patients who

received long-acting injectable risperidone than among those who received oral antipsychotics (39% after 10.8 months vs. 45% after 11.3 months; hazard ratio, 0.87;

95% confidence interval, 0.63 to 1.20). Psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, scores

on the Personal and Social Performance scale of global functioning, and neurologic side effects were not significantly improved with long-acting injectable risperidone as compared with control treatments. Patients who received long-acting

injectable risperidone reported more adverse events at the injection site and more

extrapyramidal symptoms.

Conclusions

Long-acting injectable risperidone was not superior to a psychiatrists choice of oral

treatment in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who were

hospitalized or at high risk for hospitalization, and it was associated with more local

injection-site and extrapyramidal adverse effects. (Supported by the VA Cooperative

Studies Program and Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs; ClinicalTrials.gov

number, NCT00132314.)

842

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Long-Acting Risperidone in schizophrenia

he most common and potentially

remediable cause of treatment failure in

patients with schizophrenia is lack of adherence to prescribed oral medications.1,2 By ensuring sustained levels of drug in the blood,

long-acting injectable delivery may improve adherence and symptom control and reduce the rate of

relapse and hospitalization.2-5

In the United States, the first second-generation

antipsychotic agent to be made available in a longacting injectable delivery system was risperidone

(Risperdal Consta, Ortho-McNeil Janssen). Longacting injectable risperidone may cause fewer

extrapyramidal symptoms than the long-acting

injectable first-generation antipsychotic agents.6

A randomized trial showed the efficacy of

long-acting injectable risperidone over placebo

in patients with schizophrenia,7 and before-andafter studies have shown tolerability in switching

from oral to long-acting injectable risperidone,

with improved symptoms and reduced hospital

use.8-11 These studies involved clinically stable

patients and lacked randomized control groups.

Three randomized trials that also involved patients with stable disease showed no advantage

of long-acting injectable risperidone therapy over

oral treatment.12-14

In this trial involving patients with unstable

disease, we hypothesized that long-acting injectable risperidone would be superior in reducing

the risk of hospitalization for up to 2 years as

compared with a psychiatrists choice of an oral

antipsychotic.

Me thods

Participants

Patients were eligible to participate in the study

if they were 18 years of age or older, had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as assessed with the use of the Structured

Clinical Interview based on the fourth edition of

the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,15 and were at risk for psychiatric hospitalization as evidenced by current psychiatric hospitalization, hospitalization in the previous 2 years,

or increased use of mental health services to prevent relapse as adjudicated by the study chairpersons (the first two authors). The original entry

criteria required hospitalization in the previous

year but were extended to enhance recruitment

(see the study protocol, available with the full text

of this article at NEJM.org).

Randomization began in September 2006, and

data collection continued for 3 years, with 209

of 369 patients (56.6%) randomly assigned in the

first year, 140 patients (37.9%) assigned in the

second year, and 20 patients (5.4%) assigned

during the first 3 months of the third year.

Follow-up continued for up to 2 years.

Exclusion criteria were the following: detoxification in the previous month; reported past

intolerance to risperidone or intramuscular injections; current treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotics, oral clozapine, warfarin, or

a combination of these agents; serious medical

conditions; unstable living arrangements; and a

history of assault or suicidal behavior requiring

urgent intervention.

The patients decisional capacity was assessed

with the use of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool.16 Guardian consent was allowed.

Subjects received payment for their travel expenses and time: $25 for monthly and injectiononly visits and $45 for extended quarterly assessment visits. The injectable-risperidone group thus

had more planned paid visits than the oral-antipsychotic group. After written informed consent

had been obtained from the patient or guardian,

testing for allergic reactions was performed with

an oral test dose of 1 mg of risperidone. Longacting injectable risperidone was provided free

of charge by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, which had no role in the study.

The study and consent forms were approved

by the institutional review boards of the 19 collaborating centers. The analyses were conducted

at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cooperative Studies

Program Coordinating Center, Boston, and the VA

Health Economics Resource Center, Menlo Park,

California. All authors designed the trial, interpreted the findings, agreed to publication of the

manuscript, and reviewed and approved the manuscript. The first author wrote the first draft of

the manuscript. All authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data, the data

analyses, and the fidelity of this report to the

study protocol.

Randomization

Randomization was conducted centrally and stratified according to site because of potential practice differences. Randomization was conducted

with the use of randomly permuted blocks of

variable size to ensure an approximate balance

over time.

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

843

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

Treatment Groups

m e dic i n e

Patients randomly assigned to long-acting injectable risperidone were seen clinically by a study

nurse every 2 weeks for the first month and then

monthly. All patients were seen monthly by their

psychiatrist and by the nurse. On the basis of

consensus guidelines,17 long-acting injectable risperidone was administered intramuscularly at an

initial dose of 25 mg every 2 weeks. Dosage increments of 12.5 mg were permitted every 4 weeks

at the discretion of the treating psychiatrist, up

to the maximum approved dose of 50 mg.

Steady-state drug levels are reached 6 to 8 weeks

after initiation of treatment with long-acting

injectable risperidone,17 and efforts to reduce

the use of oral antipsychotics subsequently were

encouraged in the injectable-risperidone group.

Previous oral antipsychotics were to be continued

for at least 3 weeks. Treatment interruptions

among patients randomly assigned to long-acting

injectable risperidone were addressed by restarting the intramuscular medication and providing

oral medication for 3 weeks if the interruption

occurred before the steady state was reached, or

if the interruption was longer than 6 weeks.

Concomitant psychotropic medications (i.e.,

antianxiety agents, antidepressants, and oral antipsychotics and mood stabilizers) and anticholinergic medications were allowed.

Control-group participants continued to receive oral antipsychotic therapy as prescribed by

their treating physician. Treating psychiatrists

were given a summary of optimal dosage ranges

for oral antipsychotic and anticholinergic agents,

based on published recommendations.18

baseline (on a scale of 1 to 7, with higher scores

indicating poorer functioning or less improvement). Satisfaction with medication was measured

with the use of the Drug Attitude Inventory (on

a scale of 1 to 20, with higher scores indicating

greater satisfaction).21

Retention on the assigned drug was measured

according to the number of days until discontinuation of the assigned treatment or, among participants assigned to the oral medication, days to

crossover to any new oral or long-acting injectable treatment. The use of long-acting injectable

risperidone was documented according to study

prescribing records, and the use of oral medication was documented according to patient interviews. Efforts were made to ensure that patients

continued to receive the medications selected by

their doctor if they discontinued the study drug.

Symptoms of schizophrenia were measured

according to the total score on the Positive and

Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, which ranges

from 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating

more symptoms), and its positive, negative, and

general subscales.22 PANSS ratings were obtained

from standardized videoconferences conducted

by trained raters from MedAvante who were unaware of the patients study-drug assignments.

Psychiatric assessments by video conference are

reliable in patients with schizophrenia and are

well received.23

Subjective psychological distress was measured

with the use of the depression and anxiety subscales of the Brief Symptom Index (on a scale of

0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater

distress).24

Concomitant Psychosocial Treatment

Quality of Life and Social Functioning

To ensure that no patient was randomly assigned

to less than standard best practice an ethical

imperative a short checklist of potentially useful ancillary psychosocial services available at the

participating centers was provided to all participants during follow-up visits.19

Quality of life was measured with the use of the

HeinrichsCarpenter Quality of Life Scale (ranging from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating

better quality of life)25 and the Personal and Social Performance scale (ranging from 1 to 100,

with higher scores reflecting better functioning),26 the latter providing a global assessment of

social functioning. Both were administered by

videoconference assessors who were unaware of

the study-drug assignments.

Health-related quality of life was assessed

with the use of the Quality of Well-Being scale

(ranging from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater well-being),27 which has been validated for use in schizophrenia.28

Measures

Blinded videoconference assessments were completed every 3 months on measures of symptoms,

quality of life, and functioning.

At a monthly unblinded meeting with the

study nurse, the Clinical Global Impressions

(CGI) scale20 was used to assess the patients

global mental health status and the change from

844

of

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Long-Acting Risperidone in schizophrenia

Substance Use

At screening, physicians and patients were asked

whether substance abuse was a problem. Alcohol

and drug use in the previous 30 days was assessed with the use of the alcohol and drug composite indexes from the Addiction Severity Index

(on a scale of 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating more severe problems).29

Side Effects

Neurologic side effects were measured with the

use of three scales.30-32 Sexual dysfunction was

measured with items from the Novel Antipsychotic Medication Experience Scale (ranging from

0 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse side

effects) (Ames D: personal communication).

Hospitalization and Use of Other Medical Services

Administrative data on service use, including hospitalizations, were available for all VA health services. Psychiatric inpatient admissions were identified through the VAs Patient Treatment File.

Non-VA admissions were identified according to

discharge summaries validated as psychiatric by

a physician who was unaware of the patients

study-drug assignments.

The primary outcome measure was the time

from randomization to psychiatric hospitalization (in both VA and non-VA hospitals) or, in the

case of patients who were hospitalized at randomization, the time from the date of discharge

from the initial stay to subsequent hospitalization. The key secondary outcome measure was the

change in the PANSS total score at 12 months.

Secondary analyses compared outcomes at all

time points up to 18 months, rather than the

difference between follow-up scores and baseline scores at one specific time point.

Statistical Analysis

The planned sample size of 450 patients (the

original sample size of 600 was resized because

of recruitment difficulties) provided 90% power

for analyses of our primary outcome and secondary outcome, each with a two-sided test and a

type I error of 2.5% (i.e., 1.25% in each tail). First,

a time-to-event analysis, with the use of the logrank test, compared the hazard ratios associated

with the time to the first psychiatric hospitalization. With a null hypothesis that the hazard ratio

would equal 1, the alternative hypothesis was that

for long-acting injectable risperidone versus oral

agents, the hazard ratio was greater than or equal

to 1.65 or less than or equal to 0.60. This hypothesis was derived from an assumption based on

three studies in which baseline rates of relapse

were approximately 41% in the oral-antipsychotic

group and approximately 25% in the intramuscular-medication group (i.e., a rate ratio of 1.64

[4125] corresponding to a difference of 16 percentage points [41%25%] in the annual rate of

a first psychiatric hospitalization).2,33,34 The follow-up period for this outcome was up to 2 years,

terminating with hospitalization or discontinuation of the assigned study medication.

Confirmatory Cox proportional-hazards analyses controlled for potential confounding factors.

These factors included prior use of risperidone,

history of substance abuse, and hospitalization

at the time of enrollment.

A repeated-measures mixed-effects model was

used to compare the mean change from baseline

to 12 months in the PANSS score for injectable

and oral treatments. With a null hypothesis of

no difference, the alternative hypothesis was

that the difference was greater than or equal to

5 units or less than or equal to 5 units. The

model had fixed effects for treatment group and

time (a categorical variable); the interaction of

treatment with time, site, and individual patients

were treated as random effects. A first-order

autocorrelation structure was used. The baseline

PANSS score was added to the model to assess

its effect on changes from baseline. Confirmatory mixed models were run with the PANSS

score.

Further descriptive analysis of outcome and

side-effect measures used mixed models of all

outcome data up to 18 months because of extensive sample attrition after that time. Because of

the skewed distribution of service use, the significance of differences was tested with the

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

R e sult s

Study Participants

Altogether, 1045 patients were screened at 19 VA

medical centers between 2006 and 2009, yielding

a final analytic sample of 369 patients (Fig. 1).

Five sites discontinued the study because of insufficient recruitment. Participants were hospitalized at the time of randomization (40%), had

been hospitalized within the previous 2 years

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

845

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

1045 Patients were assessed for eligibility

514 Were ineligible

110 Patients or physicians declined participation

39 Patients or physicians never called back

382 Underwent randomization

192 Were assigned to receive

oral treatment

190 Were assigned to receive

injectable risperidone

7 Declined participation

2 Declined participation

185 Received oral treatment

120 Completed study

65 Were lost to follow-up or discontinued intervention

188 Received injectable risperidone

117 Completed study

71 Were lost to follow-up or discontinued intervention

3 Were excluded because

patient did not have a

Social Security number or

did not have baseline data

1 Was excluded because

of lack of baseline data

182 Were included in analysis

187 Were included in analysis

Figure 1. Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up of the Study Patients.

(55%), or had recent increased service use indicating a risk of hospitalization (5%). At screening,

problems with medication adherence were reported for 64% of the patients; 43% of the patients

reported problems by themselves and in 60% of

the cases, problems were reported by physicians.

Active problems with alcohol or drug use were

reported for 37% of the patients; 25% were reported by the participants and 36% were reported by their physicians. There were no significant

differences between groups at baseline in this

sample of older male veterans (Table 1 in the

Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org).

Treatment and Follow-Up Assessments

For patients assigned to and receiving long-acting

injectable risperidone, at 6 weeks, 86% of injection doses were 25 mg, 11% were 37.5 mg, and

3% were 50 mg, with an average of 1.8 injections

846

per month. During the remainder of the trial,

17% of doses were 25 mg, 31% were 37.5 mg, and

50% were 50 mg, with an average of 1.5 injections per month (the percentages do not sum to

100 because of rounding). During the first 6 weeks,

40% of patients receiving long-acting injectable

risperidone received concomitant oral antipsychotics. During the remainder of the trial, 32%

of injections were accompanied by prescriptions

for oral antipsychotics during the same month.

The follow-up interview rates in the intentionto-treat analysis were as follows: 60% (223 patients) at 1 year, 46% (170) at 18 months, and

29% (107) at 24 months, with no significant differences between groups at these time points

(P=0.42 to 0.99). The mean (SD) duration of

participation was 474235 days for long-acting

injectable risperidone versus 502226 days for

oral antipsychotics (P=0.22).

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Long-Acting Risperidone in schizophrenia

Outcomes

1.0

Freedom from Hospitalization

Long-acting injectable treatment was not superior to oral treatment in the duration of adherence

to the randomized treatment (P=0.19) (Fig. 1 in

the Supplementary Appendix). Among participants receiving oral treatment, however, 21 of 182

(12%) switched to long-acting injectable risperidone an average of 153203 days after randomization. There were no significant differences with

respect to the initiation of concomitant psycho

tropic medications (Fig. 2 in the Supplementary

Appendix).

A total of 237 of 369 patients (64%) continued

to receive the study drug throughout their participation in the study. Reasons for medication

discontinuation were not significantly different

between groups (Table 2 in the Supplementary

Appendix).

With a mean follow-up of 11.3 and 10.8

months, respectively, 81 of 182 (45%) patients

receiving oral medication and 72 of 187 (39%)

receiving long-acting injectable risperidone were

hospitalized. Long-acting injectable risperidone

was not superior to oral treatment with respect

to the time to hospitalization (P=0.39 by the

log-rank test; hazard ratio, 0.87, 95% confidence

interval [CI], 0.63 to 1.20) (Fig. 2). An analysis

that excluded the 21 subjects who switched from

an oral antipsychotic to long-acting injectable

risperidone provided similar results (hazard ratio,

1.00; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.40), as did an analysis

that was adjusted for covariates (hazard ratio,

0.82; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.13).

The mixed-model analysis of the change from

baseline to 12 months in the PANSS total score

did not show superiority of long-acting injectable risperidone (P=0.72).

Further outcome comparisons across all time

points up to 18 months showed no significant

between-group differences in the PANSS total

score or subscales (Table 1, and Fig. 3 in the

Supplementary Appendix). No significant superiority of long-acting injectable risperidone was

observed on the blindly rated HeinrichsCarpenter

Quality of Life Scale or its subscales, the Personal and Social Performance scale or the selfreported Quality of Well-Being scale, the current

CGI functioning measure, or the Addiction Severity Index composite drug scores (Table 1). The

composite alcohol index of the Addiction Severity Index was higher in the oral-antipsychotic

group (P=0.04) and the Drug Attitude Inventory

P=0.39 by the log-rank test

0.8

Injectable risperidone

0.6

Oral antipsychotic

0.4

0.2

0.0

12

15

18

21

24

49

45

28

37

Months after Randomization

No. at Risk

Oral antipsychotic 182

Injectable

187

risperidone

136

136

116

110

96

92

84

82

71

65

58

53

Figure 2. Time to Hospitalization after Randomization.

In this analysis, data on patients who withdrew from the study were censored at the time of withdrawal from the study.

favored long-acting injectable risperidone (P=0.02).

Although there was no superiority of long-acting

injectable risperidone on the unblinded assessment of illness severity at each time point, the

unblinded CGI improvement score, representing

the rater-perceived change from baseline, favored

long-acting injectable risperidone (P<0.001).

Analysis of adverse events (Table 3 in the Supplementary Appendix) showed that patients who

received long-acting injectable risperidone had

more general disorders and administration site

conditions (injection-related pain or induration)

(P=0.04) and nervous system disorders (headache and extrapyramidal signs and symptoms)

(P<0.001). There were four deaths. In the injectable-risperidone group, one patient died in his

sleep from an unknown cause and another committed suicide. In the oral-antipsychotic group, one

patient died from chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease, and another from accidental drowning.

Use of Services

A larger proportion of patients receiving longacting injectable risperidone were hospitalized at

the time of randomization and they were hospitalized for more days during the period before

randomization (Table 2). After randomization,

there were no significant differences between

groups with respect to VA service use (Table 2) or

non-VA service use (Table 4 in the Supplementary

Appendix), including the number of hospital days.

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

847

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

of

m e dic i n e

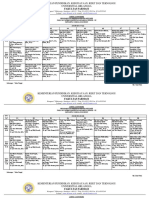

Table 1. Follow-up Assessment Outcomes Based on Mixed Models with the Use of All Available Data over All Time

Points up to 18 Months.*

Variable

Oral Antipsychotic Injectable Risperidone Mean Difference

P Value

PANSS

Total score

74.690.92

74.100.91

0.591.27

0.65

General symptoms

37.170.46

36.890.45

0.270.64

0.67

Positive symptoms

18.840.38

18.120.38

0.720.48

0.13

Negative symptoms

18.690.35

19.030.35

0.350.37

0.36

HeinrichsCarpenter Quality of Life Scale

Total score

2.860.06

2.780.06

0.080.07

0.28

Interpersonal relations

2.550.08

2.460.08

0.090.10

0.36

Instrumental functioning

2.660.05

2.650.05

0.01 0.06

0.81

Intrapsychic foundations

3.240.06

3.140.06

0.10 0.08

0.18

Personal and Social Performance Scale

53.830.78

53.640.78

0.180.90

0.84

Body-mass index

30.690.50

30.070.51

0.620.72

0.39

Clinical Global Impressions

Severity of illness

4.190.13

4.220.13

0.030.09

0.34

Change in condition

3.520.08

3.220.08

0.300.06

<0.001

0.130.03

0.070.03

0.060.03

0.04

Addiction Severity Index**

Alcohol use

0.0120.003

0.0180.003

0.0060.004

0.13

Brief Symptom Index

Drug use

0.670.62

0.640.62

0.030.06

0.55

Quality of Well-Being scale

0.660.02

0.670.02

0.010.01

0.63

Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale

0.260.04

0.210.04

0.060.03

0.11

SimpsonAngus Scale

0.230.05

0.220.05

0.010.03

0.60

Barnes Akathisia Scale

0.440.09

0.450.09

0.010.06

0.80

1.060.10

1.010.10

0.050.10

0.61

1.100.11

0.930.11

0.170.11

0.13

7.960.13

8.270.13

0.310.13

0.02

NAMES***

Sexual interest

Sexual activities

Drug Attitude Inventory

*

Plusminus values are means SE. For all outcomes, the treatment comparison was a linear contrast based on a

mixed-effects model with three fixed effects (time, treatment, and timetreatment interaction), with site as a random effect and with autocorrelated repeated measures over time.

Scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) range from 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating

more symptoms.

Scores on the HeinrichsCarpenter Quality of Life Scale range from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating better

quality of life.

Scores on the Personal and Social Performance Scale range from 1 to 100, with higher scores reflecting better functioning.

Body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Scores on the Clinical Global Impressions scale range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating poorer functioning

or less improvement.

** Scores on the Addiction Severity Index range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating more severe problems.

Scores on the Brief Symptom Index range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater distress.

Scores on the Quality of Well-Being scale range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better well-being.

Scores on the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more severe

tardive dyskinesia.

Scores on the SimpsonAngus Scale range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more severe extrapyramidal

symptoms.

Scores on the Barnes Akathisia Scale range from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more severe akathisia.

*** Scores on the Novel Antipsychotic Medication Experience Scale (NAMES) range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse side effects.

Scores on the Drug Attitude Inventory range from 1 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

848

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Long-Acting Risperidone in schizophrenia

Discussion

This randomized, controlled trial showed that in

high-risk patients with schizophrenia or schizo

affective disorder, long-acting injectable risperidone was not superior to oral antipsychotics with

respect to the primary outcome of time to hospitalization, or multiple standard measures of

symptoms, quality of life, side effects, or service

use. Greater numbers of adverse events were reported by the injectable-risperidone group. These

events primarily included injection-site phenom-

ena, headache, and extrapyramidal signs and

symptoms, suggesting that patients receiving oral

medication may flexibly adjust their medication

use to avoid such adverse effects. The duration of

treatment with long-acting injectable risperidone

was not significantly longer than the duration of

treatment with oral antipsychotics.

The findings were not modified by the addition of covariates or the exclusion of crossover

observations (for participants who switched from

oral to long-acting injectable treatment). Differences in the alcohol composite index of the Ad-

Table 2. Use of Health Services Provided by the Veterans Affairs System.*

Type of Use

Oral

Antipsychotic

(N=182)

Injectable

Risperidone

(N=187)

P Value

1.04.1

1.04.0

0.95

15.4

15.0

0.91

20.343.4

19.259.7

0.80

62.1

64.7

0.60

Inpatient care

Acute medical or surgical hospital stays

Days

Patients with any hospitalization (%)

Total acute psychiatric hospital stays after randomization

Total days

Patients with any hospitalization (%)

Hospitalization at time of randomization

Patients hospitalized (%)

Days from hospitalization at randomization to discharge

35.2

45.5

0.04

2.77.4

8.453.0

0.02

42.9

36.4

0.20

17.641.1

10.828.0

0.21

2.62.5

2.21.5

0.60

Hospitalizations subsequent to the original stay

Patients with new hospitalization after randomization (%)*

Days in subsequent stays

No. of subsequent stays among patients with any stays

Residential treatment, nonhospital

Patients with any residential treatment admission (%)

23.6

19.3

0.31

26.486.4

18.171.3

0.49

Individual psychiatry

58.965.8

52.056.2

0.67

Group psychiatry

30.163.5

24.556.6

0.36

Vocational rehabilitation

5.415.4

3.815.3

0.25

Telephone psychiatry

3.66.6

2.44.8

0.05

1.02.9

0.62.0

0.33

15.115.9

16.124.3

0.22

0.77

Days

Outpatient care

Outpatient visits after randomization (no.)

Other psychiatry

Medical and surgical

Other ancillary care

Total outpatient visits

Visits to administer long-acting injectable risperidone (no.)

22.433.3

23.140.5

136.5137.0

122.4130.9

0.26

1.24.9

19.714.7

<0.001

* These data pertain to hospitalizations at Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals only and thus the percentages are somewhat

smaller than the total proportion of patients who were hospitalized (i.e., at either VA or non-VA hospitals).

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

849

The

n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l

diction Severity Index and the Drug Attitude Inventory were not significant after adjustment for

multiple comparisons. Although the current CGI

scores assigned by raters who were aware of the

patients study-drug assignments did not differ

between groups, the CGI improvement scores assigned by these raters indicated significantly

greater improvement in the group of patients who

received long-acting injectable risperidone, suggesting an unblinded rater bias favoring longacting injectable risperidone.

Taken together, these findings are consistent

with three efficacy trials that also showed no

superiority of long-acting injectable risperidone

over oral regimens in patients with stable schizophrenia.12-14 Two studies have suggested that

unintended intramuscular injections into fat tissue may decrease pharmacologic effectiveness,

but this was not assessed in our study.35,36

Our study had several limitations. First, 12%

of control patients received long-acting injectable

risperidone treatment an average of 5 months

into the trial. This may have biased the results

in favor of oral treatment in the intention-totreat analysis. Replication of the analyses of hospitalization risk and blinded outcomes excluding

observations after these crossovers or discontinuation of long-acting injectable risperidone yielded no significant findings favoring long-acting

injectable treatment.

Second, the dose of long-acting injectable risperidone may have been inadequate in some paReferences

1. Thieda P, Beard S, Richter A, Kane J.

An economic review of compliance with

medication in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:508-16.

2. Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Cost of relapse

in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995;21:

419-29.

3. Davis JM, Matalon L, Watanabe MD,

Blake L, Matalon L. Depot antipsychotic

drugs: place in therapy. Drugs 1994;47:74173.

4. Adams CE, Fenton MK, Quraishi S,

David AS. Systematic meta-review of depot antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2001;179:290-9.

5. Hogarty GE, Schooler NR, Ulrich R,

Mussare F, Ferro P, Herron E. Fluphena

zine and social therapy in the aftercare of

schizophrenic patients: relapse analyses

of a two-year controlled study of fluphenazine decanoate and fluphenazine hydrochloride. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:

1283-94.

850

of

m e dic i n e

tients, and some injections were missed, but this

reflects the real-world practice that was the focus

of this effectiveness study.

Third, decisions regarding hospitalization

were unblinded, and the direction of any bias is

unknown. If physicians thought there was less

need to hospitalize patients, knowing that they

were receiving ample medication, the bias could

favor long-acting injectable risperidone. On the

other hand, if admitting physicians knew that

patients receiving long-acting risperidone were

symptomatic in spite of being adequately medicated, the bias could favor oral treatment.

Fourth, this sample involved older, primarily

male veterans, and results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Finally, although our revised target sample

was 450 subjects, we enrolled only 382 subjects,

and data were available for only 369 because of

early dropouts. Dropout patterns and sample

sizes were similar to those of previous schizophrenia trials.36,37 Our study did not show the

superiority of long-acting injectable risperidone,

but the confidence intervals for the time to hospitalization were fairly wide (hazard ratio, 0.87;

95% CI, 0.63 to 1.20), and the study was not

large enough to exclude modest differences

between the groups.

Supported by the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program and an unrestricted grant from Ortho-McNeil Janssen

Scientific Affairs.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with

the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

6. Miyamoto S, Duncan GE, Goff DC,

Lieberman JA. Therapeutics of schizophrenia. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle

JT, Nemeroff C, eds. Neuropsychopharmacology: the fifth generation of progress. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams

& Wilkins, 2002:775-807.

7. Kane JM, Eerdekens M, Lindenmayer

JP, Keith SJ, Lesem M, Karcher K. Longacting injectable risperidone: efficacy and

safety of the first long-acting atypical

antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:

1125-32.

8. Mller HJ, Llorca PM, Sacchetti E,

Martin SD, Medori R, Parellada E. Efficacy

and safety of direct transition to risperidone

long-acting injectable in patients treated

with various antipsychotic therapies. Int

Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;20:121-30.

9. Fleischhacker WW, Eerdekens M,

Karcher K, et al. Treatment of schizophrenia with long-acting injectable risperidone: a 12-month open-label trial of the

first long-acting second-generation antipsychotic. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:12507.

10. Lindenmayer J-P, Eerdekens E, Berry

SA, Eerdekens M. Safety and efficacy of

long-acting risperidone in schizophrenia:

a 12-week, multicenter, open-label study

in stable patients switched from typical

and atypical oral antipsychotics. J Clin

Psychiatry 2004;65:1084-9.

11. Fleischhacker WW. Second-generation

antipsychotic long-acting injections: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2009;

52:S29-S36.

12. Chue P, Eerdekens M, Augustyns I,

et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of

long-acting risperidone and risperidone

oral tablets. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol

2005;15:111-7.

13. Bai YM, Ting Chen T, Chen JY, et al.

Equivalent switching dose from oral risperidone to risperidone long-acting injection: a 48-week randomized, prospective,

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Long-Acting Risperidone in schizophrenia

single-blind pharmacokinetic study. J Clin

Psychiatry 2007;68:1218-25.

14. Keks NA, Ingham M, Khan A, Karcher

K. Long-acting injectable risperidone v.

olanzapine tablets for schizophrenia or

schizoaffective disorder: randomised, controlled, open-label study. Br J Psychiatry

2007;191:131-9.

15. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon MB,

Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview

for Axes I and II DSM IV Disorders Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research Institute, New York State

Psychiatric Institute, 1996.

16. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur

Competence Assessment Tool Treatment. Worcester: University of Massachusetts Medical Center, 1995.

17. Keith SJ, Pani L, Nick B, et al. Practical application of pharmacotherapy with

long-acting risperidone for patients with

schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:

997-1005.

18. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan

RW, et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated

treatment recommendations 2003. Schizo

phr Bull 2004;30:193-217.

19. Rosenheck R, Tekall J, Peters J, et al.

Does participation in psychosocial treatment augment the benefit of clozapine?

Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:618-25.

20. Guy W. Clinical Global Impressions

(CGI). In: ECDEU assessment manual for

psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health, 1976:

534-7.

21. Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R.

A self-report scale predictive of drug com-

pliance in schizophrenics: reliability and

discriminative validity. Psychol Med 1983;

13:177-83.

22. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

(PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull

1987;13:261-76.

23. Ruskin PE, Reed S, Kumar R, et al.

Reliability and acceptability of psychiatric

diagnosis via telecommunication and audiovisual technology. Psychiatr Serv 1998;

49:1086-8.

24. Derogatis LR, Spencer N. The Brief

Symptom Index: administration, scoring

and procedure manual. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1982.

25. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon ET, Carpenter

WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit

syndrome. Schizophr Bull 1984;10:388-98.

26. Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L,

Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability

and acceptability of a new version of the

DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;101:323-9.

27. Kaplan RM, Anderson JP. The general

health policy model: an integrated approach. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of life

and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials.

2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven,

1996:309-22.

28. Pyne JM, Sullivan G, Kaplan R, Williams DK. Comparing the sensitivity of

generic effectiveness measures with symptom improvement in persons with schizophrenia. Med Care 2003;41:208-17.

29. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE,

OBrien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv

Ment Dis 1980;168:26-33.

30. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989;154:

672-6.

31. Guy W. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). In: ECDEU assessment

manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental

Health, 1976:534-7.

32. Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating

scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta

Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970;212:11-9.

33. Herz MI, Glazer WM, Mostert MA,

et al. Intermittent vs maintenance medication in schizophrenia: two-year results.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:333-9.

34. Young JL, Zonana HV, Shepler L. Medication noncompliance in schizophrenia:

codification and update. Bull Am Acad

Psychiatry Law 1986;14:105-22.

35. Nesvg R, Tanum L. Therapeutic drug

monitoring of patients on risperidone depot. Nord J Psychiatry 2005;59:51-5.

36. Marder SR, Meibach RC. Risperidone

in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J

Psychiatry 1994;151:825-35.

37. Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner

R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in

patients with schizophrenia N Engl J Med

2002;346:16-22. [Erratum, N Engl J Med

2002;346:1424.]

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society.

new nejm application for iphone

The NEJM Image Challenge app brings a popular online feature to the smartphone.

Optimized for viewing on the iPhone and iPod Touch, the Image Challenge app lets

you test your diagnostic skills anytime, anywhere. The Image Challenge app

randomly selects from 300 challenging clinical photos published in NEJM,

with a new image added each week. View an image, choose your answer,

get immediate feedback, and see how others answered.

The Image Challenge app is available at the iTunes App Store.

n engl j med 364;9 nejm.org march 3, 2011

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 9, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2011 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

851

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Setiawan 2015Dokument8 SeitenSetiawan 2015ShibaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 4Dokument5 SeitenAssignment 4NIKITA0% (1)

- Adoc - Pub Harborne J B Metode Fitokimia Penuntun Cara ModernDokument5 SeitenAdoc - Pub Harborne J B Metode Fitokimia Penuntun Cara ModernFirdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uji Stabilitas Formulasi Krim Tabir Surya Serbuk RUMPUT LAUT (Eucheuma Cottonii. Doty)Dokument4 SeitenUji Stabilitas Formulasi Krim Tabir Surya Serbuk RUMPUT LAUT (Eucheuma Cottonii. Doty)miftahulnazifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Maserasi Hal 5Dokument8 SeitenJurnal Maserasi Hal 5ElsiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identifikasi Hidrokuinon Pada Krim Pemutih Racikan Yang Beredar Di Pasar Tengah Bandar Lampung Secara Kromatografi Lapis Tipis (KLT)Dokument8 SeitenIdentifikasi Hidrokuinon Pada Krim Pemutih Racikan Yang Beredar Di Pasar Tengah Bandar Lampung Secara Kromatografi Lapis Tipis (KLT)Chandra YuniantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dipiro PneumoniaDokument8 SeitenDipiro Pneumoniameri dayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPO High AlerTDokument19 SeitenSPO High AlerTHendraTriSaputroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Pustaka: Drug Substances and ProductsDokument2 SeitenDaftar Pustaka: Drug Substances and ProductsFaizah Min FadhlillahNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1099-1105 Ijpr1301179Dokument7 Seiten1099-1105 Ijpr1301179Indah Indryani UNoch keine Bewertungen

- FarmakokinetikaDokument142 SeitenFarmakokinetikaAstrid Bernadette Ulina PurbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analisis Deskriptif Efek Samping Penggunaan Obat Anti Tuberculosis Pada Pasien TBC Di Rsud Dr. Pirngadi MedanDokument7 SeitenAnalisis Deskriptif Efek Samping Penggunaan Obat Anti Tuberculosis Pada Pasien TBC Di Rsud Dr. Pirngadi MedanEva MelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacy Intravena Admixture Services (Pivas) : IV - Admixture Handling CytotoxicDokument32 SeitenPharmacy Intravena Admixture Services (Pivas) : IV - Admixture Handling CytotoxicintanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indonesian FDA Regulations On Indonesian Traditional Nutraceuticals (Herbs) ContributorsDokument16 SeitenIndonesian FDA Regulations On Indonesian Traditional Nutraceuticals (Herbs) ContributorsDyva VanillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pert 3. Sediaan Radiofarmasi Dan RadiolabelingDokument19 SeitenPert 3. Sediaan Radiofarmasi Dan Radiolabelingwida safitrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Farmakologi FarmakodinamikDokument26 SeitenFarmakologi FarmakodinamikMuhammad Nikko AomadaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kuliah Colon DDS Reguler-Ganjil 2010 INDDokument125 SeitenKuliah Colon DDS Reguler-Ganjil 2010 INDYartiSulistiaNingratNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bromhexin Method of Analysis PDFDokument8 SeitenBromhexin Method of Analysis PDFJitendra YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Rumus Kadar AbuDokument5 SeitenJurnal Rumus Kadar AbualyanuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biopharmaceutics Classification System-The Scientific Basis PDFDokument5 SeitenBiopharmaceutics Classification System-The Scientific Basis PDFtrianawidiacandra100% (1)

- Floor Stock AlamandaDokument2 SeitenFloor Stock AlamandayuliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coek - Info - The Pharmaceutical Codex Principles and Practice oDokument1 SeiteCoek - Info - The Pharmaceutical Codex Principles and Practice oNomiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ikatan Apoteker Indonesia (Iai) Cabang Kota BekasiDokument2 SeitenIkatan Apoteker Indonesia (Iai) Cabang Kota BekasichevyluvianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JurnalDokument4 SeitenJurnallailaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Farmasi Industri: Stabilitas ObatDokument113 SeitenFarmasi Industri: Stabilitas ObatMelani JunaediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Jurnal Interaksi Obat Antihipertensi - Radhwa Fauztina (20190350050)Dokument13 SeitenReview Jurnal Interaksi Obat Antihipertensi - Radhwa Fauztina (20190350050)Radhwa FauztinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Materi IAI Palangka Raya - Rev PDFDokument55 SeitenMateri IAI Palangka Raya - Rev PDFNopernas CahayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02-Pharmaceutical Care ProcessDokument42 Seiten02-Pharmaceutical Care ProcessBalsam Zahi Al-Hasan100% (1)

- Review On Prefilled Syringe As A Modern Technique For Packaging and Delivery of ParenteralDokument6 SeitenReview On Prefilled Syringe As A Modern Technique For Packaging and Delivery of ParenteralShivraj JadhavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Obat Aman Dan Berbahaya Untuk Ibu Hamil Dan MenyusuiDokument28 SeitenDaftar Obat Aman Dan Berbahaya Untuk Ibu Hamil Dan MenyusuiDwiPrasetyaningRahmawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review On Water Used in Pharma Industry: European Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical ResearchDokument11 SeitenA Review On Water Used in Pharma Industry: European Journal of Pharmaceutical and Medical ResearchDinesh babuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parameter FarmakokinetikDokument12 SeitenParameter FarmakokinetikNnay AnggraeniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Review MegaDokument6 SeitenJurnal Review MegaLa OgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPDokument6 SeitenPPElvina iskandarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dipiro Edisi 9 KolestrolDokument10 SeitenDipiro Edisi 9 KolestrolFriska tampuboLonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artikel 1 PDFDokument9 SeitenArtikel 1 PDFsintiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prosedur Asli IodoformDokument3 SeitenProsedur Asli IodoformtartilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uji Aktivitas Antibakteri Kombinasi Minyak Atsiri Daun Gelam Putih (Melaleuca Leucadendra) Dan Rimpang Jahe (Zingiber Officinale) Terhadap Bakteri Staphylococcus Aureus Dan Escherichia Coli Secara inDokument74 SeitenUji Aktivitas Antibakteri Kombinasi Minyak Atsiri Daun Gelam Putih (Melaleuca Leucadendra) Dan Rimpang Jahe (Zingiber Officinale) Terhadap Bakteri Staphylococcus Aureus Dan Escherichia Coli Secara inberliana faradisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bio Evailabilitas Dan Bioekivalensi Aciclovir BABEDokument13 SeitenBio Evailabilitas Dan Bioekivalensi Aciclovir BABERian Nurdiana100% (1)

- Computational Methods For Prediction of Drug LikenessDokument10 SeitenComputational Methods For Prediction of Drug LikenesssciencystuffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development and Validation of A Liquid Chromatography Method For The Analysis of Paromomycin Sulfate and Its Impurities 2155 9872.1000102Dokument4 SeitenDevelopment and Validation of A Liquid Chromatography Method For The Analysis of Paromomycin Sulfate and Its Impurities 2155 9872.1000102rbmoureNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expired DateDokument38 SeitenExpired DateAnggie Restyana100% (1)

- Monitoring Efek Samping ObatDokument8 SeitenMonitoring Efek Samping ObatWilujeng SulistyoriniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daun LeilemDokument8 SeitenDaun Leilemniken retnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analisis Simetikon PDFDokument9 SeitenAnalisis Simetikon PDFArini Musfiroh50% (2)

- Pendekatan SOAP Farmasi KlinikDokument40 SeitenPendekatan SOAP Farmasi KlinikmadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kelompok 10 - Metode Optimasi Senyawa PenuntunDokument36 SeitenKelompok 10 - Metode Optimasi Senyawa Penuntunapr_aprililianti100% (1)

- KARAKTERISTIK TUGAS DAN TANGGUNG JAWAB APOTEKER MUSLIM - NewDokument30 SeitenKARAKTERISTIK TUGAS DAN TANGGUNG JAWAB APOTEKER MUSLIM - NewBantuinAku KakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preformulasi AsetosalDokument2 SeitenPreformulasi AsetosalTazyinul Qoriah AlfauziahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bab V Analisis Farmakoterapi - DRP 5.1 Lembar Pemakaian Obat Di IGDDokument16 SeitenBab V Analisis Farmakoterapi - DRP 5.1 Lembar Pemakaian Obat Di IGDCosmas ZebuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTM Direct CompressionDokument8 SeitenCTM Direct CompressionrizkamarNoch keine Bewertungen

- OPTIMASI ZAT WARNA BUNGA TELANG (Clitoria Ternatea) Sebagai Pewarna Alami Pada Sirup ParasetamolDokument9 SeitenOPTIMASI ZAT WARNA BUNGA TELANG (Clitoria Ternatea) Sebagai Pewarna Alami Pada Sirup ParasetamolReza Fadillah AchmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glimepiride TabletDokument48 SeitenGlimepiride Tabletrabd samNoch keine Bewertungen

- AHFS Drug InformationDokument10 SeitenAHFS Drug InformationMika FebryatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 Farmakokinetika Klinik Antibiotika Aminoglikosida PDFDokument19 Seiten11 Farmakokinetika Klinik Antibiotika Aminoglikosida PDFIrfanSektionoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jadwal Ujian Sidang Periode 112 TGL 26-27 Juni 2021 (Rev)Dokument9 SeitenJadwal Ujian Sidang Periode 112 TGL 26-27 Juni 2021 (Rev)Yohan Nafisa NetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coump & Disp (B - Latifah)Dokument101 SeitenCoump & Disp (B - Latifah)Muhammad Nurhadi Bin AbdulghaffarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long-Acting Risperidone and Oral Antipsychotics in Unstable SchizophreniaDokument29 SeitenLong-Acting Risperidone and Oral Antipsychotics in Unstable SchizophreniahermanfirdausNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long-Acting Risperidone (1) .En - IdDokument10 SeitenLong-Acting Risperidone (1) .En - IdZidnil UlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Replacement The Violent Consequences of Mainstreamed Extremism by ISDDokument36 SeitenThe Great Replacement The Violent Consequences of Mainstreamed Extremism by ISDTom Lacovara-Stewart RTR TruthMediaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Evidence: Chicago Police Torture TrialDokument118 SeitenSummary of Evidence: Chicago Police Torture TrialAndres100% (1)

- NSTP (LTS) Activity 1 Ma. Nicole Pateño: 1. Give Your Own Perspective About The VMGO of BISU?Dokument3 SeitenNSTP (LTS) Activity 1 Ma. Nicole Pateño: 1. Give Your Own Perspective About The VMGO of BISU?MA. NICOLE PATENONoch keine Bewertungen

- State - CIF - Parent - Handbook - I - Understanding - Transfer - Elgibility - August - 2021-11 (Dragged) PDFDokument1 SeiteState - CIF - Parent - Handbook - I - Understanding - Transfer - Elgibility - August - 2021-11 (Dragged) PDFDaved BenefieldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy and National DevelopmentDokument8 SeitenPhilosophy and National DevelopmentIzo SeremNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tom Sawyer Vocabulary.1681608284879Dokument22 SeitenTom Sawyer Vocabulary.1681608284879Vhone NeyraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social - Security - Net - TAMIL NADUDokument4 SeitenSocial - Security - Net - TAMIL NADUTamika LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SuccessionDokument47 SeitenSuccessionHyuga NejiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual Complex Engineering Problem: COMSATS University Islamabad Abbottabad CampusDokument35 SeitenManual Complex Engineering Problem: COMSATS University Islamabad Abbottabad CampusHajra SwatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 56408e8ca7356 Allhoff 2003Dokument8 Seiten56408e8ca7356 Allhoff 2003yiğit tirkeşNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Poem For Cotton PickersDokument4 SeitenA Poem For Cotton Pickersapi-447987846Noch keine Bewertungen

- FLW Cronon Inconstant Unity Passion PDFDokument25 SeitenFLW Cronon Inconstant Unity Passion PDFAlexandraBarbieruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internship Report NgoDokument14 SeitenInternship Report Ngosamarth chauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6-Re - Petition For Radio and T.V. Coverage A.M. No. 10-11-5-SC, A.M. No. 10-11-6-SC and A.M. No. 10-11-7-SCDokument6 Seiten6-Re - Petition For Radio and T.V. Coverage A.M. No. 10-11-5-SC, A.M. No. 10-11-6-SC and A.M. No. 10-11-7-SCFelicity HuffmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Melody Gardot Your Heart Is As Black As NightDokument8 SeitenMelody Gardot Your Heart Is As Black As NightmiruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brij Pal Vs StateDokument7 SeitenBrij Pal Vs StateSatyendra ChauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position PaperDokument9 SeitenPosition PaperJamellen De Leon BenguetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Filsafat Hukum (Tri & Yusuf)Dokument5 SeitenJurnal Filsafat Hukum (Tri & Yusuf)vacefa2507Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assurance Principles, Professional Ethics and Good Governance SyllabusDokument15 SeitenAssurance Principles, Professional Ethics and Good Governance SyllabusGerlie0% (1)

- Session 5 - Marketing ManagementDokument6 SeitenSession 5 - Marketing ManagementJames MillsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abs CBN vs. Ombudsman 2010Dokument11 SeitenAbs CBN vs. Ombudsman 2010Mara VinluanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employment Contract: Prepared By: Atty. Daniel L. DiazDokument8 SeitenEmployment Contract: Prepared By: Atty. Daniel L. DiazKuya KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rakowski Complaint1 Amy MorrisDokument4 SeitenRakowski Complaint1 Amy Morrisapi-286623412Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Cincinnati Time Store As An Historical Precedent For Societal ChangeDokument11 SeitenThe Cincinnati Time Store As An Historical Precedent For Societal ChangeSteve Kemple100% (1)

- Deed of Assignment SM DavaoDokument2 SeitenDeed of Assignment SM DavaoFrancisqueteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Almirez Vs Infinite Loop TechnologyDokument2 SeitenAlmirez Vs Infinite Loop TechnologyJulian DubaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Communication 1Dokument13 SeitenBusiness Communication 1Kishan SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Online Training of Trainers' (Tot) /walkthrough of Modules ScheduleDokument5 SeitenOnline Training of Trainers' (Tot) /walkthrough of Modules ScheduleJames Domini Lopez LabianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- b00105047 Posthuman Essay 2010Dokument14 Seitenb00105047 Posthuman Essay 2010Scott Brazil0% (1)

- NOSTALGIA - Grandma's Fridge Is Cool - Hemetsberger Kittiner e MullerDokument24 SeitenNOSTALGIA - Grandma's Fridge Is Cool - Hemetsberger Kittiner e MullerJúlia HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Von EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Bewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (82)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDVon EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionVon EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (404)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityVon EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (32)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeVon EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesVon EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1412)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsVon EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsVon EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsVon EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (42)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaVon EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearVon EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (23)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossVon EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (6)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityVon EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeVon EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (254)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Von EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (110)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceVon EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (51)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsVon EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (39)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlVon EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (60)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingVon EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1138)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessVon EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (328)