Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Death of Universities

Hochgeladen von

Molitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđela0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

27 Ansichten2 SeitenTerry Eagleton

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenTerry Eagleton

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

27 Ansichten2 SeitenThe Death of Universities

Hochgeladen von

Molitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaTerry Eagleton

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 2

The death of universities

Terry Eagleton

Academia has become a servant of the status quo. Its malaise runs so much deeper

than tuition fees

Friday 17 December 2010 22.00 GMT

Last modified on Tuesday 3 June 201415.40 BST

Are the humanities about to disappear from our universities? The question

is absurd. It would be like asking whether alcohol is about to disappear from

pubs, or egoism from Hollywood. Just as there cannot be a pub without

alcohol, so there cannot be a university without the humanities. If history,

philosophy and so on vanish from academic life, what they leave in their

wake may be a technical training facility or corporate research institute. But

it will not be a university in the classical sense of the term, and it would be

deceptive to call it one.

Neither, however, can there be a university in the full sense of the word

when the humanities exist in isolation from other disciplines. The quickest

way of devaluing these subjects short of disposing of them altogether is

to reduce them to an agreeable bonus. Real men study law and engineering,

while ideas and values are for sissies. The humanities should constitute the

core of any university worth the name. The study of history and philosophy,

accompanied by some acquaintance with art and literature, should be for

lawyers and engineers as well as for those who study in arts faculties. If the

humanities are not under such dire threat in the United States, it is, among

other things, because they are seen as being an integral part of higher

education as such.

When they first emerged in their present shape around the turn of the 18th

century, the so-called humane disciplines had a crucial social role. It was to

foster and protect the kind of values for which a philistine social order had

precious little time. The modern humanities and industrial capitalism were

more or less twinned at birth. To preserve a set of values and ideas under

siege, you needed among other things institutions known as universities set

somewhat apart from everyday social life. This remoteness meant that

humane study could be lamentably ineffectual. But it also allowed the

humanities to launch a critique of conventional wisdom.

From time to time, as in the late 1960s and in these last few weeks in

Britain, that critique would take to the streets, confronting how we actually

live with how we might live.

What we have witnessed in our own time is the death of universities as

centres of critique. Since Margaret Thatcher, the role of academia has been

to service the status quo, not challenge it in the name of justice, tradition,

imagination, human welfare, the free play of the mind or alternative visions

of the future. We will not change this simply by increasing state funding of

the humanities as opposed to slashing it to nothing. We will change it by

insisting that a critical reflection on human values and principles should be

central to everything that goes on in universities, not just to the study of

Rembrandt or Rimbaud.

In the end, the humanities can only be defended by stressing how

indispensable they are; and this means insisting on their vital role in the

whole business of academic learning, rather than protesting that, like some

poor relation, they don't cost much to be housed.

How can this be achieved in practice? Financially speaking, it can't be.

Governments are intent on shrinking the humanities, not expanding them.

Might not too much investment in teaching Shelley mean falling behind our

economic competitors? But there is no university without humane inquiry,

which means that universities and advanced capitalism are fundamentally

incompatible. And the political implications of that run far deeper than the

question of student fees.

IZVOR: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/dec/17/deathuniversities-malaise-tuition-fees

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Eagleton, The Death of UniversitiesDokument1 SeiteEagleton, The Death of UniversitiesNick TsakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trembling in the Ivory Tower: Excesses in the Pursuit of Truth and TenureVon EverandTrembling in the Ivory Tower: Excesses in the Pursuit of Truth and TenureBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Misbehavioral SciencesDokument7 SeitenMisbehavioral SciencesLance GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Economic Basis of Politics (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Von EverandThe Economic Basis of Politics (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Column GelDokument2 SeitenColumn GelAngeliqueAquinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The University is Closed for Open Day: Australia in the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe University is Closed for Open Day: Australia in the Twenty-first CenturyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Justifying Culture TASKDokument3 SeitenJustifying Culture TASKfreshbreeze_2006Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2022 Theme 1 - Lit, Lang and The Mass MediaDokument25 Seiten2022 Theme 1 - Lit, Lang and The Mass Mediavisionlight.306Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bonfire of the Humanities: Rescuing the Classics in an Impoverished AgeVon EverandBonfire of the Humanities: Rescuing the Classics in an Impoverished AgeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (8)

- Perry Anderson - Components of National CultureDokument51 SeitenPerry Anderson - Components of National CultureKuriakose Lee STNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Can't The Sciences and The Humanities Get Along - The Chronicle Review - The Chronicle of Higher EducationDokument9 SeitenWhy Can't The Sciences and The Humanities Get Along - The Chronicle Review - The Chronicle of Higher EducationHyeon ChoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Study The HumanitiesDokument6 SeitenWhy Study The HumanitiesCzyenn Ghyle IgcalinosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Restoring Intellectual Coherence by Edward SaidDokument3 SeitenRestoring Intellectual Coherence by Edward Said5705robinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Science Communication Challenge: Truth and Disagreement in Democratic Knowledge SocietiesVon EverandThe Science Communication Challenge: Truth and Disagreement in Democratic Knowledge SocietiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nussbaum (2002) Humanities and Human DevelopmentDokument12 SeitenNussbaum (2002) Humanities and Human DevelopmentSérgio AlcidesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experts and the Will of the People: Society, Populism and ScienceVon EverandExperts and the Will of the People: Society, Populism and ScienceNoch keine Bewertungen

- StuartHall, EmergenceCrisisDokument14 SeitenStuartHall, EmergenceCrisisvavaarchana0Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Tragedy of Political Theory: The Road Not TakenVon EverandThe Tragedy of Political Theory: The Road Not TakenBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Scott Culture in Political Theory 03Dokument24 SeitenScott Culture in Political Theory 03Hernan Cuevas ValenzuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Studies for Troubling Times: A Multimodal Introduction to British and American CulturesVon EverandCultural Studies for Troubling Times: A Multimodal Introduction to British and American CulturesHuck ChristianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Berube, The MatterDokument7 SeitenBerube, The MatterMark TrentonNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Philosophical Approach - Practical Vol. 2Von EverandA Philosophical Approach - Practical Vol. 2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Riedel - Transcendental Politics. Political Legitimacy and The Concept of Civil Society in KantDokument27 SeitenRiedel - Transcendental Politics. Political Legitimacy and The Concept of Civil Society in KantPete SamprasNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Time for the Humanities: Futurity and the Limits of AutonomyVon EverandA Time for the Humanities: Futurity and the Limits of AutonomyBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- Utopia Thomas More ThesisDokument4 SeitenUtopia Thomas More Thesisafkoliddh100% (2)

- Plato Allen Bloom The RepublicDokument509 SeitenPlato Allen Bloom The RepublicVukan Polimac100% (1)

- Allan Bloom - The Democratization of The University (1970.ocr)Dokument28 SeitenAllan Bloom - The Democratization of The University (1970.ocr)Epimetheus in the CaveNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ethics of The Public Square: A Preliminary Muslim CritiqueDokument16 SeitenThe Ethics of The Public Square: A Preliminary Muslim CritiqueShahid.Khan1982Noch keine Bewertungen

- Liberal Arts Speech8Dokument16 SeitenLiberal Arts Speech8mehmetmsahinNoch keine Bewertungen

- STS and Public Policy: Getting Beyond Deconstruction SHEILA JASANOFFDokument15 SeitenSTS and Public Policy: Getting Beyond Deconstruction SHEILA JASANOFFUhtuNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Cultural Studies To Cultural Analysis: A Controlled Reflection On The Formation of MethodDokument13 SeitenFrom Cultural Studies To Cultural Analysis: A Controlled Reflection On The Formation of MethodtessascribdNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Posthuman - Rose BraidottiDokument7 SeitenThe Posthuman - Rose BraidottiUmut Alıntaş100% (1)

- ArtDokument2 SeitenArthanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science As A Social InstitutionDokument5 SeitenScience As A Social InstitutionHezro Inciso CaandoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gmat 3Dokument47 SeitenGmat 3harshsrivastavaalldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Universityof LifeDokument23 SeitenThe Universityof LifeSaadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Giddens 001Dokument6 SeitenGiddens 001Neelam ZahraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy DemocracyDokument22 SeitenPhilosophy DemocracyAurangzebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allan Bloom - Politics and The Arts, InTRODUCTION 1960Dokument24 SeitenAllan Bloom - Politics and The Arts, InTRODUCTION 1960Epimetheus in the CaveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science in Social ContextsDokument29 SeitenScience in Social ContextsDominic DominguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humanities Value EssayDokument21 SeitenHumanities Value EssayБенеамин СимеоновNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociology and Saint Simon by Émile DurkheimDokument190 SeitenSociology and Saint Simon by Émile DurkheimNathanCoombs100% (5)

- Towards Cosmopolitan LearningDokument17 SeitenTowards Cosmopolitan LearningSidra AhsanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why We're No Longer Buying The Humanities by April Rose FaleDokument3 SeitenWhy We're No Longer Buying The Humanities by April Rose FaleApril RoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Searle - The Case For A Traditional Liberal EducationDokument9 SeitenJohn Searle - The Case For A Traditional Liberal Education6o6xbq39ufuw2wi2Noch keine Bewertungen

- EUGPCOv 1Dokument7 SeitenEUGPCOv 1DAKSH GREAD DPSN-STDNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHARLEY Jonathan Charley - Glimmer of Other WorldsDokument14 SeitenCHARLEY Jonathan Charley - Glimmer of Other WorldsPaola CodoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Somewhat To The Embarrassment of Bloom's Thesis, Which Emphasizes The Inability of Americans To Digest Serious Thought, His Book Has Become A Popular HitDokument1 SeiteSomewhat To The Embarrassment of Bloom's Thesis, Which Emphasizes The Inability of Americans To Digest Serious Thought, His Book Has Become A Popular HitAharon RoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Social Function of Science John Desmond BernalDokument7 SeitenThe Social Function of Science John Desmond BernalThierry MéotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and IrelandDokument21 SeitenRoyal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and IrelandCaio Tácito Rodrigues PereiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Postmodern Condition: A Report On Knowledge Study GuideDokument45 SeitenThe Postmodern Condition: A Report On Knowledge Study GuideManshi YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definitions of Culture in Sociology and AnthropologyDokument4 SeitenDefinitions of Culture in Sociology and AnthropologyIARA SPORNNoch keine Bewertungen

- AristotleDokument2 SeitenAristotlepiptipaybNoch keine Bewertungen

- A History of Political Thought From Ancient Greece To Early ChristianityDokument186 SeitenA History of Political Thought From Ancient Greece To Early ChristianityMario GiakoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Službeni Katolički Blagoslov PivaDokument2 SeitenSlužbeni Katolički Blagoslov PivaMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is The REAL Douay-Rheims Bible?Dokument18 SeitenWhat Is The REAL Douay-Rheims Bible?Molitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđela100% (1)

- Katoločka Crkva Više Nije Vojujuća??Dokument5 SeitenKatoločka Crkva Više Nije Vojujuća??Molitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jude The ApostleDokument6 SeitenJude The ApostleMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gustav Vasa BIBLE, 1541.Dokument93 SeitenGustav Vasa BIBLE, 1541.Molitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđela100% (3)

- Why Were Michael and Satan Disputing Over The Body of Moses?Dokument2 SeitenWhy Were Michael and Satan Disputing Over The Body of Moses?Molitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pope Francis and The DevilDokument1 SeitePope Francis and The DevilMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Razmatranje Za KORIZMUDokument1 SeiteRazmatranje Za KORIZMUMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sveti Antun Pustinjak I Njegov Križ I Sveti Franjo AsiškiDokument8 SeitenSveti Antun Pustinjak I Njegov Križ I Sveti Franjo AsiškiMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kanonska Pravoslavna Molitva Sv. Anđelu Čuvaru Na Engleskom JezikuDokument1 SeiteKanonska Pravoslavna Molitva Sv. Anđelu Čuvaru Na Engleskom JezikuMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AngelsDokument1 SeiteAngelsMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pope Benedict XVI: The Dating of The Last SupperDokument3 SeitenPope Benedict XVI: The Dating of The Last SupperMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pravoslavna Molitva Sv. Mihaelu Na Engleskom JezikuDokument1 SeitePravoslavna Molitva Sv. Mihaelu Na Engleskom JezikuMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Padre Pio On Guardian AngelsDokument10 SeitenPadre Pio On Guardian AngelsMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exorcism Prayer of St. Michael The ArchangelDokument3 SeitenExorcism Prayer of St. Michael The ArchangelMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđela100% (7)

- How To Hear Your AngelsDokument1 SeiteHow To Hear Your AngelsMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sv. Mihael I Padre Pio - St. Michael and Padre PioDokument1 SeiteSv. Mihael I Padre Pio - St. Michael and Padre PioMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adam Sedgwick To DarwinDokument3 SeitenAdam Sedgwick To DarwinMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zaziv Sv. Mihaelu Arhanđelu Na Engleskom I Latinskom JezikuDokument1 SeiteZaziv Sv. Mihaelu Arhanđelu Na Engleskom I Latinskom JezikuMolitvena zajednica sv. Mihaela arhanđelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science of EducationDokument2 SeitenScience of EducationnoemiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constructivist LearningDokument22 SeitenConstructivist LearningJona AddatuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eureka Math Parent Tips Grade 4 Module 2Dokument2 SeitenEureka Math Parent Tips Grade 4 Module 2api-359758826Noch keine Bewertungen

- Position Description FormDokument3 SeitenPosition Description FormLailyn100% (1)

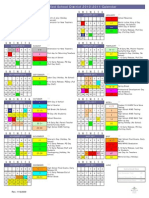

- Higley 2010-2011 District CalendarDokument1 SeiteHigley 2010-2011 District CalendarMelissaNewmanMinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment Lesson Plan LauraDokument5 SeitenAssignment Lesson Plan Lauraapi-333858711Noch keine Bewertungen

- Acticity 2Dokument2 SeitenActicity 2Shian SembriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RISD Design For Social Entrepreneurship Spring 2010 SyllabusDokument2 SeitenRISD Design For Social Entrepreneurship Spring 2010 SyllabusSloan KulperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reseach KoDokument21 SeitenReseach KoAngeloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of The K To 12 Curriculum in An Inclusive SchoolDokument88 SeitenEvaluation of The K To 12 Curriculum in An Inclusive SchoolDee Ehm HopeNoch keine Bewertungen

- UT Dallas Syllabus For nsc4366.001.10s Taught by Van Miller (vxm077000)Dokument6 SeitenUT Dallas Syllabus For nsc4366.001.10s Taught by Van Miller (vxm077000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aldrian PreliminariesDokument8 SeitenAldrian Preliminariesnosila_oz854Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan-5th GradeDokument4 SeitenLesson Plan-5th Gradesoutherland joanneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Animal Needs Lesson PlanDokument4 SeitenAnimal Needs Lesson Planapi-279301695Noch keine Bewertungen

- Narrative Report On Mpre2018Dokument3 SeitenNarrative Report On Mpre2018Maelena PregilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feasibility ReportDokument9 SeitenFeasibility Reportapi-253980970Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review Rough DraftDokument6 SeitenLiterature Review Rough Draftapi-260323951100% (2)

- Action PLanDokument5 SeitenAction PLankeira100% (1)

- Impact of Math Lab (Feedback + Testimonials)Dokument2 SeitenImpact of Math Lab (Feedback + Testimonials)Himani BakshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic 1-Teaching and Learning Materials For The ClassroomDokument20 SeitenTopic 1-Teaching and Learning Materials For The ClassroomIda Syazwani100% (1)

- Nepal: Special Education in NepalDokument8 SeitenNepal: Special Education in NepalNagentren SubramaniamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of The Project: To Show The Different Stages of The Project Implementation A. Pre-PlanningDokument7 SeitenSummary of The Project: To Show The Different Stages of The Project Implementation A. Pre-PlanningAntonio B ManaoisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Didactics of EnglishDokument18 SeitenDidactics of EnglishlicethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section 2 Quiz 1Dokument6 SeitenSection 2 Quiz 1Jawahar MuthusamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeff Duncan Andrade - Gangstas, Wankstas, and RidasDokument23 SeitenJeff Duncan Andrade - Gangstas, Wankstas, and RidaskultrueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exam Form 2 March 2018Dokument10 SeitenExam Form 2 March 2018AmetBasir100% (2)

- 2020 Third Quarter DMEA Tool For Districts 2Dokument7 Seiten2020 Third Quarter DMEA Tool For Districts 2Shannara ElliseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industrial Training Guideline 20162017 - 28mac2017Dokument24 SeitenIndustrial Training Guideline 20162017 - 28mac2017Ali AmranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Professional Growth Plan ReflectionsDokument3 SeitenTeaching Professional Growth Plan Reflectionsapi-300281604Noch keine Bewertungen

- KWL Chart Educ555Dokument8 SeitenKWL Chart Educ555Jessica DeSimoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionVon EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (51)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (30)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismVon EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (11)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessVon EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (85)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYVon EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentVon EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (17)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyVon EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (7)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsVon EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (21)

- Knocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldVon EverandKnocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (64)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthVon EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (179)

- The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersVon EverandThe Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsVon EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (10)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessVon EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (60)

- Summary of Ryan Holiday's Discipline Is DestinyVon EverandSummary of Ryan Holiday's Discipline Is DestinyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Jungian Archetypes, Audio CourseVon EverandJungian Archetypes, Audio CourseBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (124)

- This Is It: and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual ExperienceVon EverandThis Is It: and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual ExperienceBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (94)

- There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindVon EverandThere Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (71)

- Roman History 101: From Republic to EmpireVon EverandRoman History 101: From Republic to EmpireBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (59)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosVon Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (207)

- You Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsVon EverandYou Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)