Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

BB Web Ans Focus 2010 Avances en El Tto de La Ansiedad Resistente. Lanouette

Hochgeladen von

Adriana Rodriguez PalmeroCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

BB Web Ans Focus 2010 Avances en El Tto de La Ansiedad Resistente. Lanouette

Hochgeladen von

Adriana Rodriguez PalmeroCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Advances in the

Management of TreatmentResistant Anxiety Disorders

Nicole M. Lanouette, M.D.

Murray B. Stein, M.D., M.P.H.

exist, many patientspossibly even 50 60%remain symptomatic despite first-line treatments. With the exception of

obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), there are generally no universal definitions of treatment resistance and many

CLINICAL

SYNTHESIS

Abstract: Anxiety disorders are among the most common and disabling mental illnesses. While effective treatments

treatments (both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic) have not been tested specifically in refractory cases. This article reviews the evidence for possible medication, psychotherapy, brain stimulation, and neurosurgical approaches

including some promising novel treatmentsfor managing treatment-resistant anxiety.

Anxiety disorders are among the most common and

disabling of mental disorders, making them a serious public health concern (1). Anxiety disorders are

associated with an increase in physician visits and

medical costs and with reduced productivity at

home and in the workplace (2). Although many

pharmacological (and nonpharmacological) treatments exist, the evidence suggests that these disorders in many patientsperhaps as many as 50%

60%are resistant or refractory to first-line

treatments (3). This scenario speaks to the compelling need for recommendations about managing

such patients.

There are two main challenges limiting clinicians

who aim to provide evidence-based care for treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. The first is a general lack of agreed-upon definitions as to what constitutes treatment resistance in anxiety. In broad

terms, our starting point in discussing treatmentresistant anxiety will be when a patient has not responded to one of two first-line treatments, for example, a serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitor

(SSRI) or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The

second challenge is that few studies have tested

strategies in treatment-refractory cases. Unless otherwise noted, the investigations reported here were

not tested after other treatments had failed. Given

this lack of specific data, the majority of this article

is a review of first-line efficacy studies. Although

not ideal, this is the best evidence currently available that holds potential utility for treatment planning after first-line treatments have been unsuccessful. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is the

only exception; as discussed in the section on Ob-

focus.psychiatryonline.org

sessive-Compulsive Disorder, there are agreedupon definitions of treatment resistance, and strategies have been tested in patients with treatmentresistant OCD. An additional limitation of the

literature present for any disorder is publication

bias; positive findings are more likely to be published than negative results.

When facing a patient who appears to have a

treatment-refractory disorder, a critical first step is

to ensure that the patient has received adequate

first-line treatment. For example, many patients

considered to have a treatment-resistant disorder

have not yet received cognitive behavior therapy

(CBT), which is a valid first-line therapy, and once

they do receive such therapy respond well to it.

Unfortunately, access to good-quality CBT is limited in many practice settings, although computerized and Web-based delivery approaches are increasingly being investigated to increase the reach

of CBT (e.g., reference 4). Assessing adherence to

CME Disclosure

Nicole M. Lanouette, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego and VA

San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA

No relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Murray B. Stein, M.D., M.P.H., Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego, VA

San Diego Healthcare System, and Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of

California San Diego, San Diego, CA

Consultant: Bristol Myers Squibb

Address correspondence to Murray B. Stein, M.D., M.P.H., Professor of Psychiatry and Family &

Preventive Medicine, University of California, San Diego, 9500, Gilman Drive, Mailcode 0855,

La Jolla, CA 92093-0855, e-mail: mstein@ucsd.edu.

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

501

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

treatment is also useful to confirm that patients

have actually received an adequate trial of therapy and/or medication before moving on to therapies with a less well-established evidence base.

Another essential step is to reevaluate a patient

with a treatment-refractory disorder diagnostically to ensure that the principal diagnosis is correct and to ensure that there are not additional

comorbid disorders that would require a different treatment strategy.

We refer all readers to the up-to-date APA Practice Guideline for Panic Disorder (5) and Guideline (6) and more recent Guideline Watch (7) for

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as the

2007 Guideline for OCD (8), which are all excellent resources on evidence-based practice for both

initial treatment and treatment in refractory cases.

The 2008 World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines for the pharmacological

treatment of anxiety and obsessive and post-traumatic stress disorders is another excellent review of

evidence-based pharmacotherapy (9). Consultation with a psychiatrist experienced in treating anxiety disorders is also recommended when one is

establishing a plan of care after first-line treatments

have failed. At the end of each section, we include a

case vignette example demonstrating possible approaches. Readers should note that in this review,

we generally do not discuss mechanisms of actions

or adverse effects of these medications and advise

readers to be familiar with these before using the

medication in clinical practice. In addition, reviewing the evidence for complementary or alternative

treatments is beyond the scope of this review.

PANIC

DISORDER

First-line treatment for panic disorder includes

any of the following: SSRI, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (venlafaxine is the

most studied, but duloxetine has a similar mechanism of action), tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) (the

most data are available for imipramine or clomipramine; TCAs often are not used as first-line treatment because of their side effect profile), benzodiazepine (not adequate monotherapy if there is a

co-occurring mood disorder), or CBT (5).

If one first-line treatment has failed or been inadequate, augmentation with or switching to another

first-line therapy is recommended. As with other

disorders, augmentation is generally preferable if a

patient has had a partial response, whereas switching to another agent will probably be more efficacious if there has been no response. Examples of

augmentation strategies include adding CBT or a

benzodiazepine to an SSRI or adding an SSRI to

502

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

FOCUS

CBT. A common reasonable switching strategy is

to cross-titrate from an SSRI that has been completely ineffective to another SSRI, to an SNRI, or,

less commonly, to a TCA. Only one randomized

controlled trial (RCT) (N46) has systematically

studied a series of interventions in patients with

panic disorder who failed to achieve remission with

initial SSRI monotherapy (10). Simon et al. (10)

noted that 21% of patients achieved remission after

6 weeks of initial SSRI monotherapy. Among those

who did not achieve remission, increasing the dose

of the SSRI in the next phase of the study was not

effective. In the third phase of the study, remission

rates were similarly low in both groups; CBT added

to the SSRI was comparable to clonazepam added

to the SSRI. Two open, noncontrolled studies

found CBT to be effective after failed pharmacotherapy (11, 12).

Although there is little evidence specifically addressing the question of whether therapy is effective

after failure with an SSRI, examining the more substantial data on using medication in combination

with therapy as initial treatment may be informative in guiding treatment planning for the patient

with a refractory disorder. An RCT of 150 patients

with panic disorder found that the combination of

CBT and an SSRI or SSRI alone was somewhat

superior to CBT alone at the end of treatment, but

this difference was no longer significant 6 and 12

months after treatment discontinuation (13). A

2006 meta-analysis of 21 RCTs of antidepressants

and psychotherapy (mostly behavior therapy or

CBT) for panic disorder concluded that in the initial phase of treatment, the combination of an antidepressant plus psychotherapy was better than either alone. In later phases of treatment,

combination therapy remained more effective than

antidepressants alone but was no better than psychotherapy alone (14). A recent meta-analysis of

the three RCTs that studied combining benzodiazepines with psychotherapy reported that there was

inadequate evidence to draw any definitive conclusions, but all studies found no advantage for combination treatment over monotherapy (15).

MONOAMINE

OXIDASE INHIBITORS

Although there is evidence supporting their use

in panic disorder, given their many potential adverse effects, monoamine oxidase inhibitors

(MAOIs) should generally be reserved for situations in which several first-line treatments have

failed. Phenelzine has proven effective for what

would now be called panic disorder in one open

(16) and two double-blind placebo-controlled

studies (17, 18). Most studies of MAOIs were done

THE JOURNAL OF LIFELONG LEARNING IN PSYCHIATRY

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

OTHER

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

As with MAOIs, the data on other antidepressants for panic disorder are limited to populations

with nontreatment-refractory disorders. The evidence in support of mirtazapine for panic disorder

includes three open-label studies (26 28) and one

small (N27) double-blind trial showing that mirtazapine was comparable in efficacy to fluoxetine

(29). Although three small open trials found nefazodone to be potentially beneficial for panic disorder (30 32), no RCTs have confirmed this finding,

and its use is limited by the risk of liver toxicity. In

one very small (N11) single-blind trial, trazodone

was efficacious for panic disorder (33), but two

larger RCTs found it ineffective in enhancing CBT

(34) and less effective than imipramine or alprazolam (35). There is insufficient evidence to either

support or refute the efficacy of bupropion in panic

disorder; it was found to be effective in one small

open trial (36) but not in another (37).

ANTICONVULSANTS

Anticonvulsants have been investigated for panic

disorder in small studies, only two of which were

focus.psychiatryonline.org

RCTs. In one RCT, gabapentin was efficacious in

the severely ill group, but there was no overall difference between gabapentin and placebo (38). Valproate was found to be effective in a very small open

study (N13) among patients with panic disorder

and mood instability who had not responded to

CBT and a first-line medication (39). Two other

very small open-label studies also support the use of

valproate for panic disorder, but these findings require confirmation in larger RCTs before it can be

recommended, particularly given its significant side

effects. Positive results in two case series of tiagabine (40, 41), suggested it could be beneficial for

patients with treatment-refractory disorders. However, a subsequent open trial (42) and an RCT (43)

found no difference between tiagabine and placebo.

One small (N14) controlled study found that

carbamazepine was statistically, but not clinically,

more effective than placebo (44). Positive results in

one case series (N3) of vigabatrin (45) and one

(N28) open-label study of levetiracetam (46)

suggested that further study of these agents in controlled trials is warranted.

CLINICAL

SYNTHESIS

before the publication of DSM-III and therefore

did not use the panic disorder diagnosis; however,

the description of symptoms is consistent with

panic disorder. Doses found effective in those studies were fairly low, usually up to 45 mg/day. It is

possible that higher doses may be needed for patients with treatment-resistant panic disorder, but

no trials specifically address this question.

The reversible MAOIs are appealing, given that

they do not typically require adherence to a lowtyramine diet or a 2-week washout period before

starting. However, the studies examining moclobemide (which is not currently available in the United

States) for panic disorder have yielded mixed results: two studies showed positive results, finding it

comparable to fluoxetine (19) and clomipramine

(20), whereas one showed benefit only for seriously

ill patients (21), and another found no benefit over

placebo (22). Brofaromine is a reversible MAOI

that also inhibits serotonin reuptake. It is not available for use but has been found in three RCTs to be

more effective than placebo (23) and as effective as

fluvoxamine (24) or clomipramine (25). There

have been no published studies of selegiline for

panic disorder. None of the studies of MAOIs or

reversible MAOIs were specifically conducted with

treatment-resistant patients, so it is not known how

effective they would be in patients for whom an

SSRI, benzodiazepine, or CBT has failed.

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

No evidence supports the use of first-generation

antipsychotics in panic disorder. There is only preliminary positive evidence for some second-generation antipsychotics. Two open-label studies have

examined olanzapine monotherapy (47) and olanzapine augmentation after a failed SSRI trial (48)

with positive results. Risperidone augmentation

appeared to be effective for panic disorder that had

not responded to an SSRI and/or benzodiazepine in

a small 8-week open-label study (N30) (49). A

more recent randomized, rater-blinded trial

(N56) found risperidone monotherapy equivalent to paroxetine (50). An open-label study of patients with refractory panic disorder or generalized

anxiety disorder (GAD) found that aripiprazole

augmentation of an SSRI and/or benzodiazepine

significantly reduced anxiety (51). The only data on

ziprasidone for refractory panic disorder is a small

case series with positive results (52). Given the significant risk of metabolic side effects and the lack of

conclusive evidence about their efficacy, secondgeneration antipsychotics cannot be widely recommended as second-line agents in panic disorder, but

they could have utility in severe refractory cases.

OTHER

MEDICATIONS

The evidence points to buspirone monotherapy

being ineffective for panic disorder. Randomized

double-blind placebo-controlled trials have found

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

503

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

buspirone to be comparable to placebo and less effective than imipramine (N52) (53) and alprazolam (N92) (54). Another RCT (N60) detected

no difference between buspirone, imipramine, or

placebo groups (55), which the authors attributed

in part to a strong placebo response. A small

(N16) randomized study concluded that clorazepate was significantly more effective than buspirone (56). Another RCT (N91) found that buspirone did not enhance the efficacy of CBT for

panic attacks, although there was an initial benefit

at 16 weeks for agoraphobia and generalized anxiety that did not persist (57). Because buspirone is

more commonly used clinically as an adjunctive

agent than as monotherapy, controlled trials investigating its efficacy in conjunction with first-line

agents in refractory cases would be valuable.

d-Cycloserine is a partial agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor that has been shown to enhance extinction learning (58). A recent RCT lends

strong preliminary support for adding d-cycloserine to exposure-based CBT for panic disorder

(59). Although d-cycloserine requires further study,

particularly in patients in whom first-line treatments have failed, it holds promise in enhancing

CBT.

use of CBT, the evidence is sparse and essentially

nonexistent for treatment-resistant cases.

OTHER

There have not been any controlled investigations of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for

refractory panic disorder. Although most commonly performed for refractory OCD, capsulotomy, the neurosurgical technique of producing bilateral lesions in the anterior limb of the internal

capsule, has rarely been performed for severe treatment-refractory panic disorder. In their case series

of 26 patients with refractory panic disorder

(N8), GAD, or social phobia, Ruck et al. (63)

reported significant 1-year and long-term reductions in anxiety but also noted that seven patients

had substantial adverse side effects, most commonly frontal lobe dysfunction. More recently,

deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been investigated

for refractory OCD, but it has not been tested in

panic disorder. At this time, psychosurgical approaches to treatment-refractory panic disorder

cannot be advocated based on the evidence.

CASE

ANTIHYPERTENSIVES

There is little evidence on the use of antihypertensives for panic disorder and even less data on

their use in treatment-resistant disorders. One

RCT of 25 patients with treatment-refractory disorders that showed positive results supports use of

pindolol to augment fluoxetine (60), but these data

have not been replicated.

OTHER

PSYCHOTHERAPIES

There is substantial evidence to support use of

CBT, either in individual or group format, as a

first-line treatment in panic disorder (5), but there

is little evidence to guide the choice of alternative

psychotherapies in a patient in whom CBT has not

worked or in a patient who prefers another type of

therapy. A manualized psychoanalytic psychotherapy called panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy was shown to be more effective than applied relaxation training in an RCT of 49 patients

with panic disorder (61). Forms of psychodynamic

psychotherapy other than panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy have not been tested in controlled trials. Emotion-focused therapy, a supportive psychotherapy, was found to be less effective

than imipramine and CBT and comparable to placebo for panic disorder (62). In general, beyond the

504

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

FOCUS

TREATMENTS

VIGNETTE

A 23-year-old female college student with panic

disorder with agoraphobia has been taking sertraline at 200 mg/day (the highest tolerable dose for

her) for 8 weeks. She reports a significant decrease

in the frequency and intensity of panic attacks but

continues to avoid many activities because of fear of

attacks and continues to have difficulty falling

asleep because of fear of night-time panic attacks.

You add a low dose (0.25 mg) of clonazepam twice

daily. Her sleep improves, but she reports excessive

daytime sleepiness and feels cognitively dulled and

continues to have problems with avoidance. In addition, she expresses the desire to minimize the use

of medication. You refer her for CBT, continue the

SSRI at the present dose, and reduce the clonazepam to only one 0.25-mg dose at bedtime. After

12 weeks of CBT, there has been a further significant reduction in the number and intensity of attacks, and she has resumed many of the activities

she previously avoided. She finds she needs the

clonazepam only a few nights a week. After 20

weeks, her panic disorder is in remission, she continues to practice the techniques learned in CBT,

and she no longer needs the clonazepam. You develop a treatment plan with her to continue the

SSRI for another 6 months until summer break, at

which time you successfully taper her off it, with

the help of booster CBT sessions.

THE JOURNAL OF LIFELONG LEARNING IN PSYCHIATRY

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

GENERALIZED

ANXIETY DISORDER

OTHER

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

There is a general paucity of data, including even

efficacy studies in treatment-naive patients, on use

of other antidepressants for GAD. There has been

only one double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a

TCA for GAD. In their 8-week RCT (N230)

comparing imipramine, trazodone, and diazepam,

Rickels et al. (66) found all three medications superior to placebo. Although diazepam worked most

quickly, imipramine showed comparable, and on

one measure even superior, efficacy by the studys

end. That trial is also the only investigation of trazodone, which was also found to be slightly more

efficacious than diazepam at 8 weeks. There have

been no RCTs of MAOIs or reversible MAOIs

among patients with GAD. One small (N24)

double-blind, randomized trial found bupropion

XL comparable to escitalopram in anxiolytic efficacy, but there have not yet been any larger controlled confirmatory studies. Mirtazapine (67) and

nefazodone (68) have shown promise for GAD in

open trials, but larger RCTs are needed. None of

focus.psychiatryonline.org

ANTIHYPERTENSIVES

Antihypertensives have received little study for

GAD, and neither of the two published trials focused on patients with treatment-refractory GAD.

The one published RCT of -blockers (N49) for

generalized anxiety found both propranolol and

atenolol to be significantly more efficacious than

placebo for patients awaiting therapy, but atenolol

produced more intolerable cardiovascular side effects leading to more study dropouts (69). A double-blind crossover trial of clonidine (N23) for

patients with GAD or panic disorder found that it

was it modestly superior to placebo for anxiety (70).

CLINICAL

SYNTHESIS

First-line treatment options for GAD include

SSRIs, SNRIs, benzodiazepines (not adequate

monotherapy for GAD with comorbid depression),

buspirone, and CBT. As in panic disorder, if monotherapy with one of these agents is not successful, a

reasonable next step is to either 1) augment the first

agent (usually chosen if there was a partial response

to the first treatment) or 2) switch to another firstline treatment (64).

Only one study has examined whether a different

first-line treatment for GAD is effective after a first

has failed. Schneier et al. (63) examined whether

open-label escitalopram was beneficial for persistent symptoms of generalized anxiety after at least

12 sessions of CBT (65). Eight of the original 24

participants entering the study had clinically significant symptoms after 12 weeks of treatment. Four

of those eight subsequently completed 12 weeks of

open-label escitalopram treatment. Among those

four, there was a statistical trend toward pre to post

improvement on the primary outcome measure.

Although these results are suggestive of a possible

benefit, larger controlled trials are needed before

any conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy of

SSRIs for residual symptoms after CBT. There

have not yet been any studies addressing the question of whether CBT is effective for persistent

symptoms after SSRI or SNRI treatment. Likewise,

studies are needed to examine whether SNRIs are

effective after a failed SSRI trial and vice versa.

these antidepressants have been systematically

tested in treatment-refractory GAD. Overall the

scant available first-line efficacy evidence supports

imipramine and trazodone.

ANTIHISTAMINES

Two controlled trials, neither of which was in

treatment-refractory cases, support the use of hydroxyzine for GAD. In their RCT comparing hydroxyzine, bromazepam, and placebo (N334),

Llorca et al. (71) found that hydroxyzine was superior to placebo and comparable to the benzodiazepine. Lader et al. (72) studied hydroxyzine, buspirone, and placebo among 244 patients with GAD.

Only hydroxyzine, but not buspirone, was superior

to placebo on the primary outcome measure, the

Hamilton Anxiety Scale, but on secondary measures both hydroxyzine and buspirone were superior to placebo.

ANTICONVULSANTS

Pregabalin is an anticonvulsant approved for

treatment of GAD in Europe but not in the United

States. It is marketed in the United States with indications for various types of chronic pain. Six published double-blind RCTs have established the efficacy of pregabalin for GAD (7378). All of these

trials found pregabalin to be superior to placebo. In

the four studies that also included an active comparative agent, the efficacy of pregabalin was similar

to that of a benzodiazepine (73, 74, 76) and venlafaxine (77). Although most of the trials were

short-term, the one that examined continuation

treatment with pregabalin found it superior to placebo in preventing recurrence of symptoms (78). A

meta-analysis of the six RCTs found that pregabalin was effective for both psychic and somatic anxiety in a dose-dependent relationship that reached a

plateau at 300 mg daily (79).

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

505

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

The data for other anticonvulsants are less robust. There have been no RCTs examining gabapentin, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, or vigabatrin

for GAD. In the one published double-blind RCT

of valproate for GAD (N80, all males), significantly more patients in the valproate group responded compared with the placebo group (80),

but more controlled trials are needed, particularly

given the side effect profile of valproate. Although

one open-label study of tiagabine compared with

paroxetine was promising (81), three parallel-group

double-blind RCTs did not find it superior to placebo (82).

Therefore, pregabalin is currently the only anticonvulsant with sufficient efficacy data to warrant

considering its use for refractory GAD. Notably,

however, none of the investigations of pregabalin

focused specifically on patients with treatment-refractory GAD, so it remains unknown how efficacious pregabalin would be as an adjunct or standalone treatment among patients in whom a firstline treatment has failed.

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Of the typical antipsychotics, trifluoperazine carries an Food and Drug Administration indication

for short-term treatment of nonpsychotic anxiety

based on a 4-week RCT (N415) that found trifluoperazine (2 6 mg daily) to be superior to placebo for moderate to severe GAD (based on DSMIII criteria) (83). This evidence must be weighed,

however, against the significant risk of tardive dyskinesia with typical antipsychotics, particularly

with longer-term use. In addition, that trial was not

focused on treatment-refractory GAD.

The evidence for atypical antipsychotics is currently primarily limited to augmentation trials.

However, many have been conducted in patients

who have treatment-refractory GAD. Pollack et al.

(84) studied olanzapine compared with placebo

added to fluoxetine among 24 participants in an

RCT who remained symptomatic after 6 weeks of

fluoxetine. Olanzapine augmentation led to significantly more responders, but not remitters, compared with placebo, but the olanzapine group also

gained significantly more weight (84). The data for

risperidone are mixed. One RCT (N40) of risperidone augmentation for persistent GAD symptoms after at least 4 weeks of anxiolytic treatment

showed a significant reduction in symptoms compared with placebo, but response rates were not

statistically significantly different (85). A larger

(N417) RCT of adjunctive risperidone among

patients with GAD who were symptomatic after 8

weeks of anxiolytic treatment found no overall dif-

506

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

FOCUS

ference between risperidone and placebo, but

among those participants with moderate to severe

symptoms, risperidone did outperform placebo in

symptom reduction (86). Although an open-label

study of quetiapine augmentation in 40 patients

with treatment-refractory GAD suggested that it

could be beneficial, an RCT (N70) of adjunctive

quetiapine for patients remaining symptomatic after 10 weeks of paroxetine CR monotherapy failed

to find quetiapine better than placebo (87). However a recent large (N873) RCT testing quetiapine XR monotherapy compared with paroxetine or

placebo found 150 mg daily of quetiapine XR or

paroxetine to be equally efficacious in producing

remission at 8 weeks, with the suggestion that

quetiapine XR might work faster (88). Although

the results are encouraging, it should be noted this

trial was not in patients with treatment-refractory

GAD. Two small open-label trials of aripiprazole

augmentation for treatment-resistant GAD reported a significant reduction in symptoms (51,

89), but these preliminary data require confirmation in larger controlled investigations. Ziprasidone

monotherapy or augmentation was studied in an

RCT of 62 patients with refractory GAD and was

not found to be superior to placebo (90).

OTHER

MEDICATIONS

Riluzole is a glutamate modulator used in the

treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. One small open-label trial (N18) of riluzole

for GAD found that it significantly reduced anxiety

symptoms and led to a 67% response and 44%

remission rate at 8 weeks (91). Larger controlled

investigations are needed, however, particularly

given the high cost of riluzole.

d-Cycloserine has not yet been studied in human

clinical trials as therapy augmentation for GAD.

Two novel agents, agomelatine (a melatonin agonist and serotonin 5-HT2C antagonist) (92) and

deramciclane (a serotonin 5-HT2A/2C antagonist)

(93) have shown promise for GAD in RCTs in

patients with nontreatment-refractory disorders.

OTHER

PSYCHOTHERAPIES

Although CBT has the smallest average effect size

for GAD compared with the effect sizes for other

anxiety disorders (94), it and applied relaxation

therapy have the largest evidence bases in support of

them compared with other therapies in GAD (95).

Given the smaller effect sizes and the fact that some

patients might prefer other styles of therapy, it is

worth examining the evidence for other therapies.

There have not been any studies of other therapies

THE JOURNAL OF LIFELONG LEARNING IN PSYCHIATRY

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

OTHER

TREATMENTS

ECT has not been tested for refractory GAD. A

preliminary open trial of rTMS, a noninvasive technique, suggests that it could be a beneficial treatment for treatment-resistant GAD (99), but further

controlled trials are needed. There are no published

human trials of DBS in GAD. In the only published case series of capsulotomy for GAD (N13

patients with GAD), Ruck et al. (63) reported significant 1-year and long-term reductions in anxiety, but also noted that seven patients had substantial adverse side effects, most commonly frontal

lobe dysfunction. Therefore, neurosurgical techniques cannot be recommended, even for severe

treatment-refractory GAD.

CASE

VIGNETTE

A 55-year-old male veteran with GAD and major

depressive disorder and a history of alcohol abuse

(in full, sustained remission) has not responded to

40 mg/day of paroxetine (at which dose he is experiencing a lot of sedation) after 8 weeks. You switch

to fluoxetine and gradually increase the dose to 60

mg/day, which he tolerates well, and after 8 weeks

at that dose he joins a CBT group. He reports feeling so anxious that he has difficulty concentrating

in the group and continues to have difficulty sleeping at night. You add trazodone, which helps his

focus.psychiatryonline.org

sleep, but he continues to have significant daytime

anxiety and low energy and motivation. You continue the trazodone, but switch the fluoxetine to

venlafaxine XR 75 mg mg/day and gradually increase the dose to 225 mg/day. After 8 weeks at 225

mg/day, he has had significant improvement in depressive and worry symptoms and finds he is more

able to use the CBT successfully.

POSTTRAUMATIC

STRESS DISORDER

Exposure-based cognitive behavior psychotherapies [including prolonged exposure therapy and

cognitive processing therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR)] have a robust evidence base in support of their efficacy for

PTSD, and there is wide consensus that they are

first-line treatments (6, 7). The 2004 APA Practice

Guideline for PTSD recommend SSRIs as first-line

pharmacotherapy. However, since then, a 2007 Institute of Medicine review (100) concluded that

there was insufficient evidence to support the firstline use of SSRIs in PTSD because of the moderate

effect sizes (approximately 0.5) from most RCTs.

In addition, the 2009 APA Guideline Watch for

PTSD (7) concluded there has been a decrease in

the strength of evidence for SSRIs in the treatment

of combat-related PTSD based on mixed results

from recent trials of SSRIs in that specific population. While we await evidence to resolve these questions, given the relatively favorable side effect profile of SSRIs, as well as multiple RCTs (6, 7) and

meta-analyses (101, 102) in support of their use,

SSRIs continue to be a reasonable first-line pharmacotherapy choice for many patients. Another

first-line choice is an SNRI, in particular venlafaxine, for which there are multiple RCTs supporting

its efficacy in PTSD (103, 104).

Few studies have specifically looked at what to do

when one first-line treatment has failed. Simon et

al. (105) tested whether paroxetine CR added onto

prolonged exposure therapy was helpful for participants who remained symptomatic after eight individual prolonged exposure therapy sessions. They

did not find that paroxetine CR was any better than

placebo, but this result could have been due to the

fairly small sample size (N23). A randomized trial

of sertraline alone versus sertraline with culturally

tailored CBT among 10 Cambodian female refugees with PTSD who had not achieved remission

with an antidepressant found the combination

treatment highly efficacious (106), suggesting that

adding CBT to an antidepressant is a reasonable

next step option. Although there is little evidence to

guide next-step treatment choices, as with the other

disorders, a reasonable first step after failure of one

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

CLINICAL

SYNTHESIS

after nonresponse to CBT. One RCT of 57 patients

with GAD supports short-term psychodynamic

psychotherapy (STPP) as being equally effective as

CBT on the primary outcome measure (96); however, for secondary outcome measures including

trait anxiety and worry, CBT was superior. In a

randomized trial (N326) of solution focused

therapy, STPP, and long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (LTPP) for long-standing (1 year)

depressive or anxiety disorders, STPP was initially

superior to LTPP for anxiety disorders (examined

collectively), but at the 3-year follow-up LTPP

showed better outcomes (97). It should be noted

that there was no CBT or relaxation therapy comparison included, and the anxiety disorders were

not examined individually. An 11-participant open

trial of mindfulness meditation-based cognitive

therapy produced promising results, suggesting

that further study in controlled trials would be

worthwhile (98). Similarly, a treatment called integrative therapy that incorporates CBT and interpersonal emotional processing therapy was effective

in an open study of 18 patients with GAD. Overall,

the existing data most strongly support CBT or

applied relaxation.

507

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

first-line agent is to augment with or switch to another first-line agent.

TRICYCLIC

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Two 8-week trials support the efficacy of amitriptyline for PTSD. In their RCT of 46 combat veterans, Davidson et al. (107) found that amitriptyline

was superior to placebo but noted low overall remission rates (only 36% of amitriptyline and 28%

of placebo groups were in remission by the end of

the study). A head-to-head randomized comparison of amitriptyline (75 mg/day) and fluoxetine (60

mg/day) in 20 Bosnian combat veterans showed

that both produced a significant reduction in symptoms (70% for amitriptyline and 60% for fluoxetine) (108). Two RCTs of imipramine and

phenelzine found both medications to be superior

to placebo for PTSD (109, 110), although one

noted a small advantage for phenelzine over imipramine (110). In contrast, desipramine was not

found to be efficacious for PTSD, although this

result could be due to the small sample (N18)

and short duration (4 weeks) of the crossover RCT

(111). Notably, none of the tricyclic antidepressant

studies were performed specifically in treatmentresistant populations and most participants were

male combat veterans, limiting the potential generalizability of these findings.

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

The two RCTs of imipramine and phenelzine

described above provide evidence in support of the

efficacy of phenelzine in PTSD (109, 110). Another small (N13) double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study failed to find a difference

between phenelzine and placebo after 4 weeks

(112). Regarding the reversible MAOIs, only openlabel studies suggest the efficacy of moclobemide

for PTSD (113, 114), and the RCTs of brofaromine yielded mixed results (115, 116).

First-generation antipsychotics have not been investigated for PTSD in any published controlled

trials. The evidence for second-generation atypical

antipsychotics is largely limited to augmentation

studies. Risperidone augmentation has been investigated in five controlled trials with mixed results.

Three RCTs found that adjunctive risperidone was

effective particularly for the reexperiencing and hyperarousal symptom clusters in combat veterans

(126, 127) and in women who had experienced

childhood abuse (128). However, the two other

trials did not find risperidone augmentation beneficial for overall PTSD symptoms but did note improvement specifically for sleep (129, 130) and psychosis (130). The only RCT of adjunctive

olanzapine among 19 patients with PTSD with

only minimal response after 12 weeks of SSRI

monotherapy demonstrated significant improvement in PTSD, sleep, and depression symptoms,

but it led to a 13-pound mean weight gain (131).

There have been two RCTs of atypical antipsychotics as monotherapy for PTSD. Risperidone was effective for the primary outcome, an overall measure

of PTSD symptoms but not any secondary outcomes in a trial of 20 women who had experienced

sexual assault or domestic violence (132). In a small

RCT (N15), olanzapine monotherapy was no

better than placebo and caused significantly more

weight gain, but there was a high placebo response

rate (133). There have not been any RCTs of

quetiapine, aripiprazole, or ziprasidone as augmentive or monotherapy for PTSD. Overall, atypical

antipsychotics appear to be a promising but imperfect option for treatment-refractory PTSD.

OTHER

ANTICONVULSANTS

MONOAMINE

OXIDASE INHIBITORS

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

The only RCT of mirtazapine for PTSD found it

effective on some, but not all, measures of symptoms (117). Bupropion is not effective for PTSD as

demonstrated in two RCTs (118, 119), although

the primary focus of one trial was smoking cessation (119). Two RCTs of nefazodone support its

use in PTSD (120, 121), and an open-label study of

19 veterans in whom three previous medication trials had failed (122) suggests that nefazodone may

have a role in treatment-refractory PTSD, although

its widespread clinical use is limited by potential

508

hepatotoxicity. Although widely used as an augmenting agent for insomnia in PTSD (123, 124),

trazodone has only been studied in one very small

(N6) open-label trial (125) and not in any controlled studies.

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

FOCUS

Overall, there have been few studies of anticonvulsants for PTSD, and they have yielded mixed to

negative results. There are three studies with clearly

negative results: one large multicenter RCT found

no difference between tiagabine and placebo for

PTSD (134) and two RCTs in veterans found valproate monotherapy to be ineffective (135, 136). In

contrast, a small RCT (N15) showed promising

results for lamotrigine (137), but no larger follow-up studies have yet been published to confirm

or refute this finding. Topiramate monotherapy

THE JOURNAL OF LIFELONG LEARNING IN PSYCHIATRY

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

ANTIHYPERTENSIVES

Propranolol has been studied for the prevention

of PTSD in two RCTs that involved administering

it shortly after a traumatic event and then following

patients over time, with generally negative results

(140, 143). It has not been studied in chronic or

treatment-refractory PTSD. Neither other

-blockers nor calcium channel blockers have been

studied in controlled PTSD trials.

The -adrenergic antagonist prazosin has received considerable recent study specifically for

PTSD nightmares and sleep disturbance in patients

with chronic, refractory PTSD. Although there was

heterogeneity in the number and types of treatments patients had tried, all of participants had

chronic PTSD and were already taking medications

or were in therapy and could therefore be considered to have treatment-refractory PTSD. Three sequential trials (144 146) examining adjunctive

prazosin in PTSD (added to whatever stable treatment participants were already receiving) found

that it was not only effective for reducing nightmares and increasing sleep time but also helpful in

reducing overall PTSD symptoms. Raskind et al.

conducted a 20-week double-blind crossover study

(N10) (145) and a follow-up larger RCT

(N40) (144) of veterans with chronic PTSD and

found that prazosin was effective for reducing

trauma nightmares and improving sleep quality as

well as overall clinical status. Mean daily doses

(taken at bedtime) in those studies were 9.5 and 13

mg, respectively. Their third study was a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study that examined more specific sleep measures in addition to

PTSD symptoms among 13 mostly female patients

with chronic PTSD from civilian trauma (146).

They found that in addition to reducing PTSD

focus.psychiatryonline.org

symptoms overall, prazosin (mean nightly dose 3

mg) also significantly increased total sleep time,

REM sleep time, and mean REM duration.

BENZODIAZEPINES

Somewhat surprisingly, only two very small

RCTs have looked at benzodiazepines for established PTSD, with generally negative results. Braun

et al. (147) conducted a very small double-blind

crossover trial (N10) and found that alprazolam

was helpful only for nonspecific anxiety and ineffective for core posttraumatic symptoms and noted

that it produced significant rebound anxiety. Another very small (N6) randomized, single-blind

(patient), placebo-controlled crossover trial found

that clonazepam was ineffective for sleep disturbances, particularly nightmares (148). Clearly,

more work is needed to evaluate the utility of benzodiazepines for PTSD, particularly treatment-resistant cases for which benzodiazepine augmentation may be useful.

OTHER

CLINICAL

SYNTHESIS

was found to be effective in an RCT of civilian

PTSD (138). However, augmentive topiramate

was not effective in a trial of chronic PTSD in combat veterans, possibly because of a higher dropout

rate in the topiramate group (139). Gabapentin has

only been studied in one controlled 14-day trial

(N48), which compared it to propranolol and

placebo in prevention of PTSD and found it to be

ineffective in that setting (140). Pregabalin, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, tiagabine, and vigabatrin

have not been tested in controlled trials in PTSD.

Preliminary open studies of augmentive pregabalin

(N9) (141) and augmentive levetiracetam

(N23) (142) in nonresponders or partial responders to antidepressants suggest that these medications are worthy of further study in larger controlled trials of refractory PTSD.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

d-Cycloserine was investigated in one small

(N11 patients with chronic PTSD) doubleblind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in which

it was found to be generally comparable to placebo

(149). However, this study did not include psychotherapy, so it could not answer the question of

whether d-cycloserine could enhance response to

psychotherapy for patients with PTSD.

OTHER

PSYCHOTHERAPIES

Exposure-based CBTs are first-line psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD (6, 7). There have not

been any studies testing other therapies for refractory PTSD after CBT has failed; therefore, we cannot answer the most salient question of whether the

following therapies would work specifically in

treatment-refractory PTSD. However, we review

the evidence for them in patients with nontreatment-refractory PTSD, as it could be helpful in

guiding treatment planning after first-line strategies

have failed.

EMDR therapy incorporates exposure-based

therapy with guided eye movements, recall, and

verbalization of traumatic memories. Although

many individual EMDR studies have been small,

meta-analyses support the efficacy of EMDR for

PTSD (150, 151). There have been conflicting results of meta-analyses comparing the efficacy of

EMDR with that of CBT (152, 153). Given that

EMDR includes a type of exposure therapy, the

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

509

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

question of whether the eye movements are an essential feature of EMDR has been raised (154). A

1999 critical review (155) and a 2001 meta-analysis

(152) found that the eye movements were neither

necessary nor sufficient for efficacy of EMDR, but

this finding is still being debated (156).

One controlled trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy (N112) found it comparable to trauma

desensitization and hypnotherapy and concluded

that all three therapies were superior to a wait-list

control (157, 158). A meta-analysis that included

psychodynamic psychotherapy also supports its efficacy for PTSD (158). A more recent randomized

trial of 32 veterans with chronic PTSD comparing

hypnotherapy or zolpidem added to an SSRI and

supportive therapy found hypnotherapy effective in

reducing PTSD symptoms and as effective as zolpidem in number of hours of sleep but superior in

improving sleep quality (159).

OTHER

TREATMENTS

Although ECT has not been studied in controlled trials of PTSD, there have been recent

promising results from studies of rTMS, particularly higher frequency right-sided rTMS. In their

RCT of low-frequency (1 Hz) rTMS, high-frequency (10 Hz) TMS, and sham rTMS for 24 patients with PTSD, Cohen et al. (160) found that 10

daily treatments over 2 weeks of 10-Hz rTMS applied to the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

(DLPFC) were superior to both low-frequency and

sham TMS in producing a significant reduction in

PTSD symptoms. In a recent RCT, Boggio et al.

(161) compared 20-Hz rTMS applied to either the

right or left DLPFC with sham rTMS. Similar to

the study of Cohen et al., the treatments were administered in 10 daily sessions over 2 weeks. They

found that both right and left DLPFC rTMS were

effective in reducing PTSD symptoms, but right

rTMS had a greater effect and led to additional

improvements in mood and overall anxiety. These

benefits persisted at the 3-month follow-up. Osuch

et al. (161) examined in a sham-controlled crossover study whether 20 sessions of 1 Hz rTMS therapy delivered over 35 sessions per week could enhance prolonged exposure therapy among nine

patients with chronic, treatment-refractory PTSD

(162). Overall, they did not find a statistically significant difference between the sham and active

treatment, but hyperarousal symptoms were more

improved in the active group.

No neurosurgical techniques have been investigated for PTSD.

In summary, despite many cases of PTSD being

resistant to existing treatments, very little available

510

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

FOCUS

evidence exists to guide treatment decisions. Lacking this evidence, the available literature suggests

that augmentation with atypical antipsychotics

may be beneficial in some patients. Given its preliminary promising results, prazosin should be

more formally studied in treatment-resistant PTSD

algorithms.

CASE

VIGNETTE

A 45-year-old female business executive with

PTSD from a rape in college was unable to tolerate

one SSRI (escitalopram) because of initial activation and increase in anxiety. She has a history of

alcohol abuse in full, sustained remission, so she

asks to avoid any potentially addictive medications.

You start a more sedating SSRI (paroxetine) at

night, which she is better able to tolerate. After 4

weeks of a full dose, she reports improvement but

continues to have poor sleep and nightmares. She

declines CBT because of schedule constraints. You

maximize the dose of the SSRI and add prazosin

initially 1 mg at bedtime for a week. You gradually

increase the prazosin 1 mg every 12 weeks, and

once you reach 4 mg nightly, she reports a significant decrease in nightmares and improvement in

her sleep. She also reports that her daytime concentration and irritability have improved and she feels

less on guard and is better able to tolerate reminders of the rape.

OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE

DISORDER

First-line treatment for OCD includes CBT

[specifically exposure and response prevention

(ERP), at least 1320 weekly sessions with daily

homework] and/or an SSRI, typically at high doses

for at least 8 12 weeks (8). Clomipramine is also

highly effective for OCD, but it is generally recommended that an SSRI be tried first, given the more

favorable side effect profile of SSRIs (8).

OCD is the only anxiety disorder for which there

are generally agreed-upon definitions of nonresponse. In OCD trials, nonresponders are typically participants whose Yale-Brown Obsessive

Compulsive Disorder Scale (Y-BOCS) score has

decreased 25% or less from baseline or who have

been rated less than much improved on the Clinical

Global Impressions-Improvement scale (163).

These definitions are not, however, universally

used, and considerable heterogeneity among nonresponders remains, leading experts in the field to

call for more scientifically validated measures of response (163). In addition, many patients called responders remain symptomatic (8, 163).

If one first-line treatment has failed or has been

THE JOURNAL OF LIFELONG LEARNING IN PSYCHIATRY

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

MONOAMINE

OXIDASE INHIBITORS

MAOIs have not been investigated for treatment-refractory OCD in controlled trials. The

only published RCT of an MAOI as initial therapy for OCD generally found that phenelzine

was ineffective and fluoxetine was effective, although the subgroup with symmetry obsessions

did respond to phenelzine (172). The reversible

MAOIs including moclobemide, brofaromine,

and selegiline have not been investigated in controlled trials of OCD.

OTHER

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

The other antidepressants have not been studied

specifically for OCD that has not responded to

first-line treatments. An initial treatment trial of 12

focus.psychiatryonline.org

weeks of open-label mirtazapine followed by 8

weeks of double-blind placebo-controlled discontinuation found it to be effective for OCD (173),

but additional RCTs have not yet been conducted.

A single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

trial found that mirtazapine added to citalopram

accelerated treatment response, but responder rates

at the end of the trial were similar in the citalopram

plus placebo and citalopram plus mirtazapine

groups (174). There have not been any RCTs of

nefazodone for OCD. A small open investigation of

bupropion did not find it effective for OCD (175).

The only RCT of trazodone for OCD found that it

was ineffective for OCD (176).

ANTICONVULSANTS

CLINICAL

SYNTHESIS

inadequate, augmenting with or switching to another first-line therapy is recommended. As with

other disorders, augmentation is generally preferable if a patient has had a partial response, whereas

switching to another agent will probably be more

efficacious if there has been no response. Examples

of augmentation strategies include adding CBT to

an SSRI or adding an SSRI to CBT. There is evidence, mostly open trials (164 166), but also two

controlled trials (167, 168), in support of adding

CBT after inadequate response to an SSRI. There

have not been any trials examining whether an

SSRI is effective either as monotherapy or augmenting treatment after nonresponse or a partial

response to CBT. A common reasonable switching

strategy is to cross-titrate from an SSRI that has

been completely ineffective to another SSRI, clomipramine, or an SNRI (8). Surprisingly, few controlled studies specifically addressed the question of

whether a second serotonergic antidepressant is effective after another failed. In one randomized,

double-blind, crossover trial, 150 patients with

OCD were randomly assigned to receive either paroxetine or venlafaxine ER. After 12 weeks, the 43

nonresponders were switched to the other agent for

12 weeks. The authors found that 42% of nonresponders benefited from switching to the other

agent (169). Although venlafaxine ER and paroxetine were both initially comparably effective

(170), in the latter part of the trial, paroxetine was

superior to venlafaxine among nonresponders to

the previous agent (169). Interestingly, a placebocontrolled trial of intravenous clomipramine found

it effective for patients with OCD who had not

responded to oral clomipramine (171), but the

clinical use of intravenous clomipramine is limited

by the need for cardiac monitoring.

There have not been any controlled trials of anticonvulsant monotherapy either for initial treatment or treatment for nonresponders. The one randomized, but open-label study of gabapentin added

onto fluoxetine suggested that it could accelerate

the treatment response but did not lead to better

outcomes at any time point after 2 weeks (177).

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

The vast majority of published RCTs of antipsychotics for OCD have studied adding an antipsychotic after insufficient response to an SSRI. The

overall results have been mixed, with the exception

of risperidone, for which results were generally positive. In an RCT, haloperidol added to fluvoxamine

was effective for treatment-refractory OCD, but

only among those patients with both OCD and tics

(178). Randomized placebo-controlled trials of

olanzapine and quetiapine augmentation have

yielded mixed results. One RCT found that olanzapine augmentation was efficacious (179),

whereas another found no difference compared

with continuing monotherapy with an SSRI (180).

Two RCTs with positive results support quetiapine

augmentation (181, 182), but three RCTs with

negative results did not find it effective (183185).

The two published RCTs comparing augmentive

risperidone with placebo for refractory OCD found

it efficacious (186, 187). A head-to-head, singleblind, randomized study comparing olanzapine to

risperidone augmentation in SSRI nonresponders

found that both medications were effective for

OCD but found limited tolerability for both (due

to amenorrhea with risperidone and weight gain

with olanzapine) (188). Li et al. (189) studied risperidone and haloperidol in a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial and found them to be

equally efficacious, but risperidone was superior for

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

511

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

depressive symptoms and was better tolerated overall. Using these data, Bloch et al. (190) conducted a

meta-analysis and concluded that atypical antipsychotics, particularly risperidone, could be useful for

augmentation in treatment-refractory cases of

OCD. They noted that the evidence was too mixed

to conclusively either support or refute using olanzapine and quetiapine (190). Matsunaga et al.

(191) conducted a 1-year study of antipsychotic

augmentation for SSRI nonresponders (191). In

that trial, 90 patients were initially treated with an

SSRI for 12 weeks, followed by the addition of

CBT for 1 year. Patients who had less than 10%

reduction in OCD symptoms after 12 weeks of the

SSRI (N44) were also randomly assigned to receive olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone augmentation of the SSRI for 1 year in addition to

CBT. The authors noted that although the SSRI

nonresponders had a significant reduction in OCD

symptoms, their initial and final Y-BOCS scores

were higher than those of the SSRI responders, and

they experienced significant side effects from the

antipsychotic augmentation (191). One promising

open-label investigation of aripiprazole augmentation for treatment-refractory OCD (192) suggests

that it is worthy of further study in larger controlled

trials.

OTHER

MEDICATIONS

Benzodiazepines have received surprisingly little

study for OCD, and there have not been any controlled trials in treatment-refractory cases. Clonazepam has been studied as an initial therapy with

mixed results. Of the monotherapy studies, one

found that it was effective (193), whereas another

did not (194), and the one augmentation study

found no difference with placebo (195). Although

one small RCT (N18) found that buspirone

monotherapy was comparable to clomipramine for

treatment-naive patients (196), when studied as an

adjunctive agent for refractory OCD, its efficacy

was not supported by the results of controlled trials

(197199). An open-label investigation of riluzole

with positive results suggests that it could be worthy

of further study (200). Lithium was not found to be

an effective adjuvant treatment for refractory OCD

in two small controlled trials (201, 202). One of

those small studies also failed to find that triiodothyronine added onto clomipramine was helpful

for clomipramine nonresponders (202). A small

(N23) randomized, placebo-controlled crossover

study found that adding once-weekly morphine

(30 45 mg) to SSRIs outperformed placebo

among participants in whom two to six previous

SSRI trials had failed (203), but further investiga-

512

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

FOCUS

tions are needed. Likewise, promising results of a

single-blind case-control study of 44 patients with

severe treatment-refractory OCD suggests that memantine is worthy of further study (204).

Two small double-blind placebo-controlled

studies, one in chronic OCD (205), of single-dose

dextroamphetamine (30 mg) found that it produced a significantly greater reduction in symptoms compared with placebo (205, 206). A more

recent 5-week double-blind study (N24) of dextroamphetamine (30 mg/day) or caffeine (300 mg/

day) added to an SSRI/SNRI after nonresponse

(207) found that both agents produced significant

decreases in OCD symptoms.

Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of d-cycloserine added to CBT found

that it enhanced response to CBT, particularly in

the initial phases of treatment (208, 209). Neither

of these studies was conducted specifically with a

medication-resistant population, so it is still not

clear whether d-cycloserine would be beneficial in

treatment-refractory OCD.

ANTIHYPERTENSIVES

Pindolol augmentation was found to be effective

in one small RCT in treatment-refractory OCD

(210), but it did not show benefit in augmenting

the initial response to fluvoxamine in another small

RCT in treatment-naive patients (211). The sole

randomized double-blind study of clonidine in patients with nontreatment-refractory OCD found

that it was ineffective (193).

ANTIHISTAMINES

The same study that found clonidine ineffective

for OCD also found that diphenhydramine produced a significant reduction in symptoms, although it was intended to be a nonactive comparator (193). However, this study was not in patients

with treatment-refractory OCD, and there have

not been any other studies of it. There have been no

investigations of hydroxyzine in OCD.

PSYCHOTHERAPY AND OTHER PSYCHOSOCIAL

TREATMENTS

CBT for OCD can focus primarily on behavioral

techniques as in ERP therapy or primarily on cognitive techniques. ERP in a variety of different settings (individual, group, therapist guided, and patient-controlled) has been the most extensively

studied and consistently has demonstrated efficacy

for OCD, leading to its being a first-line treatment

for OCD (8). No controlled trials studying other

THE JOURNAL OF LIFELONG LEARNING IN PSYCHIATRY

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

therapies after a failed trial of ERP have been conducted.

Although there have not been controlled trials,

large open studies of both partial hospitalization

(212, 213) and intensive residential treatment

(214 218), including long-term follow-up after

discharge (212, 217), suggest these are worthy of

consideration for severe treatment-refractory

OCD.

TREATMENTS

Various ablative neurosurgical techniques, including anterior capsulotomy, gamma-knife radiosurgery, and cingulotomy, have been tried for severe treatment-refractory OCD, but only in case

reports and uncontrolled studies (219 224).

Therefore, it is difficult to interpret the reported

response rates of up to 50%. In addition, the potential adverse effects, including psychosis, seizures,

personality change, hydrocephalus, and executive

dysfunction, indicate that ablative neurosurgery

should be reserved for only patients with severe

OCD for whom multiple first- and second-line

agents have failed (8). More recently, the less-invasive technique of DBS (in which electrodes connected to a stimulator are neurosurgically placed

into the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule

and ventral striatum) has shown promise in two

small studies. A small (N4) study of DBS that

included a blinded on/off phase showed significant

benefit during the blinded treatment in one participant and moderate benefit for another during open

follow-up (225). More recently, Goodman et al.

(226) conducted a sham stimulation-controlled

study of six patients with severe treatment-refractory OCD and found that DBS led to a significant

response in four participants after 12 months of

stimulation.

The only evidence in support of ECT in treatment-refractory OCD is a case series of 32 patients

(227). Therefore, although the case series reported

generally positive results, given the risks of anesthesia and memory loss, there is insufficient evidence

to support the use of ECT for OCD, although it

may have utility when there are co-occurring conditions for which ECT is indicated, such as depression (8).

Recently rTMS, a noninvasive technique, has

been investigated for a variety of psychiatric disorders including OCD. The early sham-controlled

studies of rTMS for OCD used a low frequency (1

Hz) over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

(228, 229) or right prefrontal cortex (230); none

showed benefit for OCD symptoms. With use of

those three studies, a recent meta-analysis (231)

focus.psychiatryonline.org

CASE

CLINICAL

SYNTHESIS

OTHER

concluded that rTMS was ineffective for OCD.

Consistent with those studies, a more recent shamcontrolled trial of 10 sessions of high-frequency (10

Hz) rTMS over the right prefrontal cortex failed to

find benefit for OCD symptoms but did note significant decreases in depression and overall anxiety

symptoms (232). In contrast, two recent sham-controlled studies of low-frequency (1 Hz) rTMS to

different brain regions, including the orbital frontal

cortex (233) and bilateral supplementary motor

area (234), showed significant benefit for OCD

symptoms in patients with medication-resistant

OCD, suggesting that larger trials of rTMS on

these brain regions are warranted.

In summary, there have been more studies done

for treatment-refractory OCD than for any other

anxiety disorder. Although further investigations

are needed, particularly for patients in whom multiple first- and second-line treatments have failed,

there was sufficient evidence for the authors of the

OCD APA Practice Guideline to outline a treatment algorithm (8).

VIGNETTE

A 33-year-old unemployed man with severe

OCD who you see through a public mental health

clinic had no appreciable improvement in symptoms after 10 weeks of citalopram 60 mg/day. You

switch to another SSRI (fluoxetine) and titrate up

to his maximally tolerated dose (80 mg/day). After

8 weeks, he reports a decrease in the intensity of

obsessions and a slight decrease in time spent on

compulsions but continues to have significant distress. CBT for OCD is not available in your community. You add low-dose risperidone augmentation (initially 0.5 mg at bedtime and then increase

to 1 mg at bedtime after 1 week) and continue the

high-dose SSRI. After another 4 weeks, he has had

a significant reduction in symptoms but not

enough that he has improved functionally (i.e., he

still spends many hours per day performing compulsions). You increase the risperidone to 1 mg

b.i.d., and within 2 weeks he notices that it is easier

to distract himself from his obsessions and the time

spent on compulsions has reduced enough that he

is able to start searching for work.

SOCIAL

PHOBIA

First-line therapy for social anxiety disorder, also

called social phobia, includes SSRIs, the SNRI venlafaxine ER, and/or CBT (9, 235). Phenelzine is

also effective for social anxiety disorder but given

the more favorable side effect profile of SSRIs or

venlafaxine ER, it is recommended that phenelzine

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

513

LANOUETTE AND STEIN

be tried second-line (9). Clonazepam also has demonstrated efficacy for social phobia, but only for

short-term treatment; therefore, it is typically best

used as an addition to an SSRI or SNRI, either

when starting the SSRI/SNRI to give initial symptom relief or in treatment-refractory cases (9).

As with the other anxiety disorders, if one firstline treatment has failed or been inadequate, augmenting with or switching to another first-line

therapy is the recommended next step. If a patient

has had a partial response, augmentation is typically

recommended, whereas switching to another firstline agent will probably be more efficacious if there

has been no response. Examples of augmentation

strategies include adding CBT and/or clonazepam

to an SSRI or adding an SSRI to CBT. Although

there is little specific data to guide switching after

SSRI nonresponse, most experts recommend

switching from a failed SSRI to another SSRI, venlafaxine ER, or phenelzine (9).

There are no studies on augmenting CBT with

medication or vice versa after monotherapy with either has failed. However, studies on combining medication and therapy for initial treatment of social anxiety disorder have been conducted with mixed results.

Recently Blanco et al. (236) reported the results of

their RCT (N128) comparing phenelzine, cognitive behavior group therapy (CBGT), or their combination for initial treatment of social anxiety disorder.

They found that combination treatment was most efficacious; in addition, phenelzine was superior to placebo but CBGT was not. In contrast, an RCT

(N295) of fluoxetine, CBGT, or their combination

found that all treatments were superior to placebo by

the end of the study, with no advantage for combination therapy (237). Therefore, although there is no

specific evidence to guide second-step treatment

choices after failure of one first-line agent, given the

strong evidence base for SSRIs, venlafaxine, phenelzine, and CBT, switching to another of these agents or

combining medication and CBT would be a reasonable next step. Extremely limited evidence exists on

what to do for social anxiety disorder after two firstline treatments have failed. Therefore, in the following

we review available evidence for other treatments,

most of which is from nontreatment-refractory cases.

MONOAMINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS AND

TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS

As described above, four RCTs support of the

efficacy of phenelzine as an initial treatment for

social anxiety disorder and, therefore, it should be

considered in patients for whom a first-line treatment has failed (9). Multiple double-blind trials

demonstrate the efficacy of the reversible MAOIs

514

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

FOCUS

including moclobemide (238 242) and brofaromine (243245) in nontreatment-refractory social

anxiety disorder, although brofaromine is not currently available for use, and moclobemide is not

currently approved for use in the United States. A

small 6-week open-label study of low-dose oral selegiline (10 mg/d) suggested that it had modest efficacy for social phobia (246).

There are no controlled trials of TCAs for social

anxiety disorder.

OTHER

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

The data in support of mirtazapine are limited to

one open trial with positive results (247) and one

RCT with positive results among 66 women with

social anxiety disorder (248); neither study was in

patients with treatment-resistant disorders. The

one RCT (N105) of nefazodone found that it

was ineffective for social phobia. Bupropion and

trazodone have not been studied in controlled trials

of social anxiety disorder.

BENZODIAZEPINES

Clonazepam is the only benzodiazepine that has

been studied in controlled trials for the treatment of

social anxiety disorder. Clonazepam monotherapy

has been shown to be more efficacious than placebo

(249 251), including use for long-term treatment

(249), and with efficacy comparable to that of CBT

(252). One RCT of 28 patients with social anxiety

disorder found clonazepam added to paroxetine to

be more efficacious than paroxetine alone on some,

but not all, outcome measures, although the authors noted that this result could be attributable to

inadequate power (253). Although none of these

investigations were in patients with treatment-refractory disorders, the first-line efficacy of clonazepam and the different mechanisms of action of

benzodiazepines and SSRIs/SNRIs suggest there

may be a role for adding clonazepam to an SSRI or

SNRI after a partial response.

ANTICONVULSANTS

None of the investigations of anticonvulsants

have focused on patients with treatment-refractory

social anxiety disorder. The most promising data

for anticonvulsants in patients with nontreatmentrefractory disorders are RCTs in support of gabapentin (N69) (254) and high-dose (600 mg/day)

but not low-dose (150 mg/day) pregabalin

(N135) (255). Although levetiracetam initially

appeared promising in an open-label study (256), it

was subsequently found to be ineffective for social

THE JOURNAL OF LIFELONG LEARNING IN PSYCHIATRY

FOCUS

Fall 2010, Vol. VIII, No. 4

Quetiapine (a)

Risperidone (m)

Olanzapine (a)

Olanzapine (m)

Tiagabine

Trifluoperazine (m)

Olanzapine (a)

Risperidone (a)

First line

Propranolol

Carbamazepine

Risperidone (m)

Monotherapy

Pindolol (a)

No data

d-Cycloserine

No data

No data

Antipsychotics

Buspirone

Adrenergic agents

Antihistamines

Other medications

rTMS

DBS

No data

Atenolol (m)

d-Cycloserine (a)

Oxytocin (a)

Morphine (a)

Lithium (a)

No data

No data

rTMS

Dextroamphetamine

Triiodothyronine (a)

Atomoxetine

d-Cycloserine (a)

No data

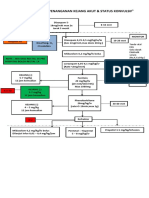

, RCT with positive results; , RCT with negative results; , RCT with mixed results (e.g., benefit for one subgroup only). The number of the above symbols next to a particular treatment indicates the total number of RCTs

that have been published testing that treatment for that disorder. First-line: the treatment has enough evidence that it is considered a first-line option. No data: there have been no published RCTs of this treatment. Insufficient

data: the RCTs of this treatment were too small to draw conclusions. Bold entries indicate that the study was in patients with treatment-refractory disorders. (a), treatment was studied as an augmentation strategy; (m), treatment was studied as a monotherapy strategy.

Note that this table summarizes the data only from published randomized, controlled trials of treatments that are available in the United States. Please see the text for details of these studies as well as for a summary of openlabel trials and studies of treatments not currently available in the United States.

No data

uncontrolled study only

d-Cycloserine (m)

Diphenhydramine

No data

Hydroxyzine

Pindolol (a)

Augmentation

Pindolol (a)

Monotherapy

Augmentation

Quetiapine (m)

Olanzapine (m)

Levetiracetam

Pregabalin

Gabapentin

Clonazepam first line

Nefazodone

Mirtazapine

Phenelzine first line

No data

Social Phobia

Monotherapy

Risperidone (a)

Haloperidol (a)

No data

Clonidine

Prazosin (for nightmares/sleep)

Insufficient data

Topiramate (a)

Topiramate (m)

Lamotrigine

Valproate

Clonidine

Ziprasidone (m, a)

Quetiapine XR (m)

Quetiapine (a)

Olanzapine (a)

Risperidone (a)

Valproate

Tiagabine

Pregabalin

Clonazepam (a)

Gabapentin

Clonazepam (m)

Trazodone

Tiagabine

Insufficient data

Nefazodone

Bupropion

Mirtazapine (a)

Phenelzine

Anticonvulsants

Bupropion XL

Trazodone

Mirtazapine

Phenelzine

First-line

Trazodone

Mirtazapine

Other antidepressants