Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

A. Mears, 'Seeing Culture Through The Eye of The Beholder. Four Methods in Pursuit of Taste'

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous iPCA22OsUOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A. Mears, 'Seeing Culture Through The Eye of The Beholder. Four Methods in Pursuit of Taste'

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous iPCA22OsUCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Seeing Culture Through the Eye of the Beholder: Four Methods in Pursuit of Taste

Ashley Mears

Assistant Professor

Department of Sociology

Boston University

Abstract

When it comes making aesthetic decisions, people commonly account for their taste with

intuition. A cultural good, symbol, or object is simply right and respondents know it

when they see it. This essay investigates the cultural meanings professional tastemakers

see as they make such deliberations, while also illustrating the problems sociologists have

in seeing culture. Using the case of fashion model casting and scouting, I present four

methods to trace how cultural producers recognize and value models looks in the global

fashion market, demonstrating how each method results in a different emphasis on how

culture is used to acquire and deploy aesthetic sense. First, interviews capture

justifications of aesthetic decisions, as well as general processes about day-to-day work

routines, which are next tested with network analysis, the second method, which

emphasizes structural arrangements in taste decisions. The third method, ethnography,

discovers taste as a situated form of knowledge production, and emphasizes culture in

interaction. The fourth and related method, observant participation, sees taste as

phenomenological as culture becomes embodied and tacit consciousness. Each of these

methods is an optical device which renders a particular and complimentary account of

taste and which affords researchers a certain way to see how culture works.

Keywords

Incipient taste, cultural production, valuation process, fashion, looks

Words: 10,596

Prepared for Special Issue, Measuring Culture at Theory and Society

Correspondence with Author: Ashley Mears, Department of Sociology, Boston

University, 96 Cummington Mall, Boston MA 02215. Telephone: 617-358-0637.

Email: mears@bu.edu.

Introduction

Writing in 1969, sociologist Herbert Blumer noted with curiosity the behavior of fashion

buyers in the womens garment industry in Paris. He was struck by how extensive the

selection process was even though it yielded only a handful of new designs each season.

Despite working relatively independently of each other, garment buyers together

converged on these few designs. On the surface however, when asked about their

preferences, buyers could only explain that they liked the garments they found personally

stunning (1969, p. 280).

Decades later, as I spent time among designers and fashion show producers in

New York and London as part of an ethnography of the fashion modeling market, I

witnessed the formation of the modeling market as a winner-take-all structure, with a

handful of superstars at the top of a huge pile of struggling competitors (Frank and Cook

1995). Not only do most high-fashion models have very similar looks in terms of height

(between 59 and 511), weight (34 bust-24 waist-34 hips), and physiognomy (with

young, typically white, and symmetrical faces), additionally there is remarkable

convergence on which models are chosen for high-end fashion jobs (Godart and Mears

2009). These models are simply understood by producers as being the really good

girls, and though they profess their tastes as personal feelings, they feel it together.

If models are chosen according to personal taste, how does this unwittingly

converge into a collective trend? We see this problem repeatedly in the sociology of

culture, where fashion dynamics operate in domains far beyond dress (Aspers and Godart

2013): people think they are relying on personal feelings and judgments when making

aesthetic deliberationsin everything from the choice of their babys name (Lieberson

2000) to their tastes for music (Salganik et al. 2006) yet somehow everyone happens to

decide similarly at the same time, thus establishing observable patterns in taste among

social groups. Cultural meanings obviously play a role in shaping peoples behavior, but

how do they emerge simultaneously? Blumer reasoned that cultural producers do a lot of

work to be in fashion and to anticipate what he described as incipient and inarticulate

tastes, a sense for what will crest into a trend in the proximate future. Incipient taste must

emerge, he thought, from shared cultural understandings, in which buyers and designers

are all chasing the future direction of fashionableness. Unlocking the ways in which this

collective taste emerges, Blumer reasoned, is at the heart of understanding cultural

change. Yet it poses a methodological problem, for if incipient taste is both invisible and

a guiding force of social action, how does the sociologist detect, let alone measure, it?

Working myself as a fashion model for two years during a qualitative study of the

fashion modeling industry, I attended dozens of castings, photo shoots and runway

shows, both as an observer and as an observant participant (Waquant 2004). I attended

organized scouting events in major cities, interviewed freelance scouts about their search

for new faces across Eastern Europe and Russia, and sat with casting directors as they

auditioned models for their Fashion Week catwalks in New York and London. I talked

with modeling agents, casting directors, magazine editors, stylists, and designers at work

and after hours in bars, parties, and at their homes, eventually interviewing a sample of

20 bookers (agents who represent models) and 20 clients (people who hire models for

work), and 12 scouts (freelancers and agency employees who travel extensively in search

of models).

4

Through each contest, casting, show, sleek design studio and squat Russian office

building, I took notes on the form and content of these interactions. I listened to how

agents and clients spoke to one another and to models, how they interacted with each

other as well as with the materials at hand: bodies, pictures, or clothing. I focused my

field notes around the problem of evaluation and valuation in those banal moments of

routine workcould I tell what looks were valuable, for instance? How did feelings shift

and change over the course of an interaction, or with a garment perhaps? How do these

tastemakers know which bodies will be fashionable, something which they must

continually reassessed, since fashion is by definition change? And empirically, what are

the best ways that I could know how they know?

This paper unpacks how a personal felt sense of taste is shared among different

people. In what follows I reflect on four complementary research strategies I used to

access how cultural producers mobilize culture as they do the work of deciphering and

making trends in the fashion model industry: interviews, network analysis, participant

observation, and embodied ethnographic practice. Each method highlights a set of

mechanisms and processes of taste formation, and each suggests a particular

conceptualization of culture. Fashion editors and model scouts use discourses of intuition

to account for their sense of good girls, which they explain as the outcome of their

eye, an embodied skill they deploy to recognize the future direction of fashion in the

hundreds of new faces they screen for modeling jobs each year. However, interviews

misrecognize as intuition what network analysis reveals to be macro structural alignments

in the field, as well as contingent interactions that unfold through ethnography. While

each can be used as a standalone method, they generate the most comprehensive

understanding when used together.

What follows in not a full account of what taste is a cultural field, but rather, I

give a narrative of a research process in pursuit of taste, and the different theoretical

orientations at which this select roster of methods arrives. As the biography of a research

problem, this paper shows how different kinds of methods let us see different angles of

culture at work, while allowing that there remain aspects of incipient taste that

researchers may simply not be able to measure, but can describe with self-reflection.

Sociological theories of taste, and the role of culture in it, depend in part on the methods

employed. This inquiry suggests that sociologists allow a plurality of conceptualizations

of culture and embrace multi-methods approaches to measuring culture.

Evaluating Taste, Seeing Culture

The problem of distinguishing quality in markets for symbolic goods, in this case the

looks of women,1 is one of valuation and evaluation, a staple inquiry in cultural sociology

that underlies questions of knowledge and expertise (Benzecry and Krause 2010),

markets and the construction of worth in economic systems (Beckert and Aspers 2011),

and inequality and hierarchy formation (Bourdieu 1984; for a review see Lamont 2012).

It is also central to the sociology of cultural objects, which tries to understand how

meanings are mobilized into aesthetic form as cultural objects (Griswold 1986).

1

Women are the focus of this paper because they receive the bulk of attention in fashion, likely resulting

from the size of womens fashion and the related gendered construction of womens display value.

6

Fashion modeling is a good case to examine valuation as both an economic (as in

price) and a cultural process (as in worth). In the fashion model market, a models

looka combination of personality and physicalityis available for rent to clients,

including editors, fashion designers, photographers, and stylists seeking to hire models

and use their images for advertising. Bookers broker the trade, in exchange for a charge

of 20% commission from both the model and the client. Looks are a type of aesthetic

good because of their high aesthetic and symbolic value, which must be converted into

commodities for economic exchange in what Joanne Entwistle has dubbed the aesthetic

economy (Entwistle 2009). Unlike commodities, models are unique, they are a type of

good that Lucien Karpik calls singularities, which require special work to ascertain their

worth (2010).2 At the same time, models cohere into looks that are articulated as

stylistically similar. While individual models are unique and their success is

unpredictable, looks can coalesce around boundaries, much like books in genres within

the literary field.

The fashion market is also a useful case to investigate the processes through

which cultural values as discernments of worth among a large pool of similarly

beautiful women get translated into market action, that is, how do shared sensibilities

orient the choice of any given model? Models are a case to see how group culture

emerges, and how people reach consensus on unspoken and ambiguous things. This

paper documents how people get on the same page without explicitly trying to or even

knowing that they are. Like choosing a babys name (Lieberson 2000), in choosing

models there are no obviously right answers, no ultimate authority and no rule-making

2

In a similar vein, Patrik Aspers calls these status markets, as opposed to standard markets (2009).

organization that governs the selection process. The problem of Which model? is

insoluble, and yet it gets resolved every day (e.g. Bielby and Bielby 2994).

To account for taste, one sociological tradition follows structural analyses of

class. Writing at the turn of the 20th century, Veblen characterized acts of consumption as

acts of invidious comparison, a framework that inspired Simmel on fashion trends and

later Bourdieu, who analyzed taste as a form of status distinction, thus coupling culture

and class structure (Bourdieu 1984; Simmel 1957; Veblen 2007 [1899]). Contrary to

prevailing theory at the time, Blumer saw taste not as something governed by

demonstrations of elite status, but as driven by a desire to be aligned with the preferences

of the social zeitgeist (1969, p. 289). Tastemakers seemed to be collectively groping in

anticipation of the next fashion trendthey are seeking to catch the proximate future,

to name the direction of modernity, the sense of modern style (1969, p. 280). To Blumer,

there must be something in the air, or in shared social space of cultural economies, that

enables producers to reach consensus on the incommensurable, and importantly, these

meanings are not static. Cultural meanings are communicated, interpreted, and reworked

in everyday practice (1937).

Culture can be both rooted in status hierarchies and worked out in interactions,

but any explanation of how culture works owes its genesis to the methods used to study

it. In the sociology of culture, researchers have struggled with how to measure culture in

accounting for social outcomes (Ghaziani 2009). The case of fashion modeling illustrates

that there are many ways to try to understand how meaning emerges and informs agents.

In what follows, I move across four methodological terrains of taste, each one shining a

spotlight into the conceptual blind spots of another. I end with a fragmented account of

incipient taste which, when taken as a whole, links culture from across micro and macro

levels of analysis.

The First Method: Interviews

The casting director Jordan Bane is in charge of choosing models for the

celebrated luxury fashion houses of Europe. His posh London studio is lined with stacks

of art books, magazines new and old, and his walls feature, among collectible artworks,

an assortment of Polaroid pictures of girls haphazardly hung with scotch tape. Some of

them are full-length body shots, some smiling, most are staring out blankly into the

room. Jordan and his assistant sort through 100 images of models a day, or about 3,000

faces a year, emailed to his office by agencies around the world. He describes his job as

that of an editor: My main role is to service designers to provide them with a suitable

kind of look of girl thats appropriate for their ethos and their world, basically.

I first met him in castings for Fashion Week shows, each one taking the form of a

handshake, a brief and generic chatWhere are you from?then he would take a

quick snapshot photograph and ask to see me walk down the length of the room and

back. When he agreed to be interviewed, I was thrilled at the chance to ask Jordan what

it is that he looks for in all those castings, and how a Polaroid makes its way around the

world into his office, and how a client like himself makes the decision to choose any

particular model. Though we talked for almost an hour, he could never quite find the

words to explain it.

9

Jordan explains that he just knows what hes looking for, and he knows it when

he sees it. Echoing the words of the other clients and agents I interviewed, Jordan is

guided by what is commonly called their eye for looks, a sixth sense or embodied

register that tells them, physically, when a look is right. Having a good eye means

predictive capability: Jordan can see a face that others will recognize as right for this

moment in fashion.

Oftentimes, clients speak of seeing value in previously unknown faces as an act

brave discovery. They talk about these moments as great personal triumphs, like

pioneers striking gold among piles of rocks. Finding her is like finding a needle in a

haystack. On his discovery of Tatiana a few years ago, a teenage girl who became a

Vogue cover girl and minor celebrity, Jordan explained, I could tell the moment I saw

Tatiana. When I found Tatiana, thats like and he snapped his fingers, continuing:

It does something very physical, I mean it really does, and I think its

really obvious when its that kind of physical. Its a taste, its purely taste.

How else can you describe that? Why did I decide to buy this chair and

sofa? You know, for me, it ticks the box. You know its an internal thing!

- Jordan Bane, Casting Director for 20 years, London

They talk about the physical sensationsgoose bumps, butterflies, gut reaction

or they refused to elaborate, ending the discussion at, You just know. Howard Becker

noted that artists and mediators may not be able to put into words the principles by which

they make their choices. Rather, they use insider lingo to convey if it swings in jazz,

10

or it works in the theatre (Becker 1982, p. 200). But they cannot state in advance what

led them to this one choice, so obvious after-the-fact. So how do they know it when

they see it, if they cannot actually name it?

Had Jordan Bane been schooled in the language of sociology, he might call it

habitus in the sense of an internal steering mechanism that feels like second nature

(Elias 1994 [1939])), or as a feel for the game, that pre-discursive familiarity with the

world one learns through practice (Bourdieu 1990: 66). Or, if he preferred cognitive

psychology, he may describe his eye as practical consciousness, an automatic sense of

attraction and repulsion. While each concept describes a place in the mind and body

where taste resides, neither concept tells us much about how taste forms or changes

direction.

Blumer ran into the same problem. His Parisian garment buyers answered in an

honest yet largely uninformative way, simply viewing some dresses as intrinsically and

obviously superior, while he could see no appreciable differences in the designs (1969:

279). He reasoned that buyers collectively and unwittingly grope for the proximate

future of fashion to express the zeitgeist. So, sitting there next to the powerful casting

director Jordan Bane, I wanted to know, does he grope?

If he does, the interview is a fraught tool for documenting it. By professing his

visceral reactions to the right girls, Jordan also professes the strength of his eye, thus

solidifying for the researcher and for himself his professional competence. If we look to

interviews to understand what motivates clients tastes, we are likely to find unreliable

and even contradictory answers (Vaisey 2009). Respondents know with certainty a good

face, and yet they dont know how they know it. They can identify, yet they cant

11

identify their criteria of identification. In fashion, interviewees can certainly explain the

why of their tastes. But asking them why happens to be a pretty bad question, which

can only be imagined post-hoc. The very fact they cant put it in words suggests a more

complicated social process with multiple moving parts, probably beyond the sight of any

given respondent.

Interviews can provide valuable insight into the who, what, when of their decision

processes, revealing the logics that govern what they are looking for. In our

conversations, I learned that the majority of clients had backgrounds in the arts, either

attending art and design colleges or holding previous positions in culture industries.

They were voracious consumers of fashion, reading the same blogs and magazines, and

in the same way: no so much reading but looking through the images, noting which

models had become campaign girls and which photographers had changed or

consistent styles.

In interviews, clients and agents alike emphasized what they call personality.

Consider the following account offered by a model scout, on what she looks for in a

roomful of girls she considers for modeling contracts:

Its just a face which is unique. Its hard to say. Its really something that you

just feel, you just see, and you just say, Wow. Um, its something that you

never saw. And when you see the gorgeous face, you see it is the main thing.

There is something. And not just the beauty, but the personality inside, you can

see personality in her eyes, for example.

- Masha, Model agency owner and scout for 7 years, Moscow

12

Personality comes up time and time again in my interviews. Clients are

concerned to discover the real or authentic selfhood of their models, which is crucial

to establish a fit with the image of the brand or design they are advertising (see also

Sadre-Orafai 2009). As a word, personality does not tell us much; it seems to just

restate the ambiguities of the look. And yet, when probed, the prominence of personality

reveals a great deal. For instance, a casting director said the following, when I ask her,

How do you size up a model? What do you look for when they come to meet you?

But I think its really about the confidence, something key. Eileen Ford [of Ford

Models] famously said that they have the X-factor. Its almost like you know

it. Theres a certain degree of confidence, a certain ease, and you know, theyre

not scared, theres no fear. We try and create an environment where people arent

scared, like hi, how are you, what do you do, you know? We have dogs, cats,

kids, like its definitely an environment that I wouldnt mind walking into.

- Rayna, Casting director of 17 years, New York

Sitting in Raynas casting studio in downtown New York, it was indeed a welcoming and

comfortable space. Rayna was wearing a beanie cap and and oversized sweater,

teenagers with headphones around their necks were chatting with her associates, indie

rock music was playing in the background. What Rayna was looking for was someone

with whom she could get along in such a space, someone who fit the surroundings and,

by implication, the hip downtown fashion designers she serviced. Almost all clients ask

13

to see a walk for show castings, which captures more than her technical capacity to wear

high heels and stand straight. This also captures the subtle cues of self, which they

describe as confidence, or a vibe, style, and feeling. They can likewise explain

which personality traits they dislike, explained a designer:

I think a lot of it too has to do with the personally, like I saw Kim [who did the

show last season] and she was telling me how things are really going the way she

wants in modeling. Like, I dont think shes booking a lot, and I dont think Im

going to cast her this time, because shes sort of negative, and I dont want that

coming out on me in my show.

- Kathy, Fashion designer of 5 years, New York

Interviews thus cue up the interactional nature of taste and its discovery in face-to-face

meetings, in which something happens that clients know is important, even as they are

hard pressed to discursively account for it.

Interviews also tell us what people do once theyve put their finger on the right

look. They feel it and sense it butterflies and goose bumpsand then they act on it.

This takes the form of decisive action: making a phone call, confirming the booking, and

spreading the word. In so doing, they tap into their social connections. Back in Raynas

office, I asked her what she does when she finds the right model:

Rayna: I get on the phone, and my first thing is Ill call my clients. Ill call a few

key photographers that we work with, like you should see this kid. Because its

14

exciting and it also, you know, everyone is looking, our business is entertainment.

Were essentially looking to get excited, and to be part of something new.

Having been a model, and I was a stylist assistant and I worked at a magazine, I

think the key is youre never one person in this business, youre a team of people.

So for me, I can recommend her, they might not like her when she gets there.

Chances are they do because I have a good relationship with my clients and Ive

had the same clients since I started.

In describing her actions, Rayna indicates the importance of information sharing

and of her own status in adding value to a models look; again this cues to the role of

social interaction. Despite their own adherence to the romantic myth of the isolated

artistic creators, producers talk about their work revealed considerable reliance on their

peers. Interviews let me see the role of gossip and information sharing in the market,

albeit from a limited vantage point. Clients noted with pride how they spread the word to

their peers. Agents send fresh faces to clients with whom they think she will be valued,

and clients share new finds with each other. When a client wishes to hire models for an

upcoming job, they place her on option, giving the client the right but not the

obligation to hire her. Agents know the value of options, that they can spread news of

them to other clients to get a bandwagon effect going. Raynas own work biography,

holding multiple positions in fashion over the last two decades, lets her see the field and

enact influence within it. These diffusion mechanisms enable a shared sense of taste to

emerge across disparate yet connected actors.

Rayna also confirms the shared stakes of wanting to be a part of the cutting edge

15

of fashion, and the emotional stakes in potentially creating a next top model. The

excitement is conveyed in interviews; the tenor in their voices gets higher and they talk

faster when describing discovery moments. Interviews, Pugh notes, are important not

just for what people say, but how they say it. Such emotional valences signal the things

that respondents find meaningful (Pugh 2013: 54).

Because interviews afford a forum for the performance of the ideal self, they

offer what Pugh calls honorable data, or that which informants deploy to make

themselves dignified in narratives about their actions (Pugh 2013). One way they do this

is by boundary symbolic boundaries between themselves and others whom they do not

want to look like. One of the first clarifications any agent or client will make about their

work is which segment of the market they service, editorial or commercial fashion, a key

marker of worth in the industry that parallels Pierre Bourdieus outline of the art field, as

a tension between avant-garde and commercially-successful art (Bourdieu 1993). In the

fashion field, editorial models tend to make less money, but they are considered more

prestigious than their commercial peers.

Models in each end of the market also have different looks. An editorial model is

typically described as having an unusualor to use a term that comes up often in the

businessan edgy look, perhaps not immediately recognizable as valuable to field

outsiders. This differs from the conventionally attractive models sought after for

commercial work, which bookers describe with terms like wholesome and girl-nextdoor, the kind that is legible to a mass middle-market. The editorial look, however, will

not make sense to the masses, nor should it. Explained one scouts assistant based in

Moscow as she talked about Polaroid pictures:

16

You see, this girl is good. She is pretty. But she is only pretty. She doesnt have

anything specific. Shes too nice looking. So she can be only for catalogues

But this one, she has something specific! Or, look at this new Prada girl, shes

nothingshes not beautiful. But, she has something! Some image in it,

something which works, at this moment, it works!

- Ekat, Scouts assistant for 3 years, Moscow

Recognition of the editorial look requires a sharper eye acclimated to the edgy

and more volatile taste of high-end editorial fashion. Those who cant see it are relegated

to the lower status commercial market. Models that work too often in catalogues are

thought to embody the less prestigious work in the very ways they move and pose; they

do lame poses from which more refined women in high fashion are immune.

Interviews revealed some of the boundary work producers undertake to distinguish their

taste from others. By focusing on how producers draw boundaries between themselves

and others, interviews give us a sense of where people stand in relation to each other, and

where they want to be (Lamont and Molnar 2002).

Despite their rhetoric of individual taste and gut instinct, clients seem to rely quite

a bit on one another to inform their decisions, in ways they may not even recognize.

Vaisey argues that interviews give access to how respondents talk and think

deliberative cognitionbut respondents cultural schemas and frames of reference reside

elsewhere, inaccessible to an interview questionnaire (Vaisey 2009). Gut instincts are

misrecognized and talked over as deliberations in interviews. In a similar way,

17

interactional aspects of social behavior appear to be talked over in interviews, minimized

and misrecognized with a discourse of individual proficiency.

As these tastemakers indicate, the actual naming of the right look is an

interactional and situated process, an act that is embedded in relationships between

clients and agents and models, all of whom are situated in relation to the field of fashion.

Thus while interviews in this project serve as a barometer to point to the things that

matter, the mechanisms of how and which things matter call for a set of tools.

The Second Method: Network Analysis

Like fashion intermediaries who choose models because they are good, Pierre Bourdieus

respondents in Distinction surely all thought they listened to good music. Such

accounts, however, elide identifiable patterns that sociologists can access beyond

interviews. To Bourdieu, the sense of good taste, or unconscious dispositions of the

habitus, cannot be understood without simultaneous reference to capital and field.

Bourdieu grounds an actors dispositions in the deployment and reproduction of his or

her mix of capitals, and taste is one vehicle actors wield in their struggle to climb to

better and more respected positions in their social space (1984). One way to identify the

field is through network analysis, to see whose taste aligns with whom.

The interviews so far suggest that producers tastes take shape through 1)

socialization in a professional and highly sociable environment, and 2) gossip and the

options hiring system that enables, but does not mandate, fashion houses to coordinate

18

their choices of models. I knew that gossip and options are important since clients

brought them up in interviews, but I didnt know the broader significance of these

mechanisms. Based on the work of scholars like Podolny (2005) and the classics like

Simmel (1957), as well as hints in the interviews themselves, it seems reasonable to think

that status structures some of this collective choice-making.

With co-author Frederic Godart, we mapped out the pattern of collective taste

using social network analysis of one season of data from Fashion Week show records on

Style.com, and found that high status houses share the current crop of in-demand models,

while lower status houses tend to choose less popular models, a clear core-periphery

structure (Godart and Mears 2009). This tells us that a status structure is tied to

designers seemingly personal taste and what they called gut instincts. The right looks

are strongly correlated with the status of fashion houses, suggesting that designers look to

their high-status peers to guide their choice of models.

Sociologists find that uncertainty in markets is overcome with market

coordination devices, or what Lucien Karpik calls judgment devices (2010). Such

mechanisms, such as guidebooks and critics, rankings, brand identities, and networks all

render transactions possible because they provide consumers with credible knowledge

make reasonable choices. For clients to make their selections of models, they rely on a

set of informal judgment devices, or network sources of information (Karpik 2010, p.

45). These take the shape of gossip and information sharing, which takes a good deal of

participation in fashions social scene. During Fashion Week, the more formal device of

optioning enables information sharing. Options indicate which houses are considering

19

hiring which models; as such, options communicate the status of a model by revealing the

status of her clients.

We concluded from these results that convergence on incipient taste happens in

three ways: 1) shared social space among clients and agents 2) information sharing

among them, and 3) status signaling with a network of fashion clients. Producers in

fashion share tastes along networks of peers, both as a way to align themselves vis--vis

other fashion houses, and because they talk to one another. However, we were left with a

few alternative explanations. It could be the case that there really are meaningful

distinctions between different candidates that designers and casting directors can

ascertain at castings, which we sociologists cannot detect; perhaps here is where

socialization into the field makes all of the difference, to decipher ambiguities like

personality and fit. We like to think this is unlikely, since models are groomed and

screened by selective bookers into a fairly homogenous pool of contenders before being

sent out to meet Fashion Week clients, but shy of experimental evidence, this cannot be

ruled out. For example, in their virtual online experiment called Music Lab, Salganik and

co-authors found musical preferences, in the form of song downloads, were highly

sensitive to other peoples preferences (Salganik, et al. 2006). Time-series data could

isolate the effects of status over different seasons, measuring the likelihood of one house

choosing a model after another house chooses her. Assuming the model stays relatively

constant, such a longitudinal technique could further isolate social influence effects on

taste.

Social network analyses are increasingly being employed to understand cultural

processes (Pachucki and Breiger 2010). One critique of this method for the study of taste

20

hinges on selection effects: networks such as this one in fashion demonstrates structural

effects on behavioral outcomes, but many outcomes could reflect selection effects of

particular types of people who enter into those networks. While a plausible claim in the

fashion worldafter all, from interviews we have seen that backgrounds in the arts and

art school were shared by manythe fact of a priori shared culture among producers

does little to explain the ebb and flow of their tastes from season to season, or the subtle

differences among the producersthe stylistic prise de distance described by Bourdieu

([1992] 1996) and Grenfell and Hardy (2003) in which fashion houses attempt to

distinguish themselves from their competitors while keeping some similarities in order

not to be seen as unfashionable in the field (Godart 2012). While people likely learn

what good taste is from years in the business, broad processes of socialization cannot

explain how collective convergence happens at particular moments and unevenly among

all of the people working in fashion. In other words, it does not matter that the fashion

industry is composed of producers who have been selected because they share tastes,

since the fashion process itself triggers differences in taste that structure the industry and

competition.

By mapping the patters of tastemakers arriving at incipient taste, we discovered a

status structure that guides fashion producers choices, and based on the interviews, it is

reasonable to conclude that information-sharing via networks propel the collective search

for the right looks. Network analysis is good at these capturing macro-patterns of social

interaction that might otherwise be invisible, and it can document patterns of similar

tastes among buyers. Further work by Godart et al. (2013) has shown that the mobility of

21

designers across fashion houses is an additional mechanism through which tastes and

styles diffuse and emerge.

The network analysis further reveals a contradiction between what interview

respondents say and how they act. In interviews, clients employed the rhetoric of

individual, personal taste, but in the network analysis, their choices are structured around

status hierarchies and imitation. This should be no surprise, as many ethnographers have

noted, an interview is also a performance site for posturing, and what people say may

contradict what people do in practice (most recently, see Jerolmack and Khan 2013).

But if interviews suggest that taste emerges from internalized norms and

capacities, network analysis arrives at a structural perspective of culture, and depicts

incipient taste as the result of both shared meanings and status signaling. This structural

perspective situates taste as a tool in struggles over capital, and culture becomes a

strategic resource available to climb hierarchies. This structural account of culture in a

Bourdieusian field gains much from a macro level of analysis. It misses people in

interactions. While network science depicts ties between clients, we have yet to see how

they relate to each other in actual space, rather than abstract social space. As it turns out,

interactions among tastemakers in particular situations play a crucial role in their

aesthetic decisions.

The Third Method: Participant Observation

22

Working as a model in the field, I had insider access and could watch taste

enactments and distinctions unfold in casting situations. Observing intermediaries at

work lead to several insights about taste as interactive knowledge, and about culture as

shared understandings of the world, grounded in people doing things together (Eliasoph

and Licthermann 2003). At casting auditions, the problem of incipient taste presents

itself yet again, now in real time:

I enter the casting for a Fashion Week show, one which presents the collections of

several designers. I ask the front desk person if Ill be meeting all of the

designers. She says no, the shows director knows what kind of vibe each

designer is going for, so shes screening which models they will see. She

explains, that this decision is not just about clothes, but rather, Its the clothes

and the person, and the energy they bring to it. I accept this explanation but am

puzzled, especially about what my own energy is or is perceived as being. When

I meet the shows director, she scans my portfolio, thanks me for coming, and

tells me Im going to meet three different designers, down the hall. At the first

stop, I greet a team of designers and one stylist. They look at me, smile, and one

designer says to the other: Shes perfect! The other one, without pause, agrees:

Youre our girl! What other shows are you doing, they ask, and when I tell

them a few names they nod approvingly. I try on three different outfits, and it

seems that with each change, they talk more excitedly about how good the clothes

look.

23

. Later backstage at the show, I learned that the designers had put in the

following instructions to the shows producers, when asked what kind of models

they were looking for: Models should be interesting, a size 6 or larger size 4,

some curvy and some straight. Also they can be white, black, Asian, and also

mixed races. I guess that is about all of them. Its difficult to specify but

basically they should be interesting looks.

My meeting with these designers was fortuitous indeed; the only criteria they had

specified was that candidates be interesting, a term that describes no more than

personality. It seems they did not know what they were looking for, and yet, they

knew precisely in the moment.

Naming the right look hinges upon a range of contingencies. Clients are attuned

to the field, to what has come before and is happening currently. In addition, we see from

the network analysis that they are sensitive to status considerations, which can raise the

value of a model and a trend in looks. What participant observation brings to the study of

incipient taste is its interactional nature. The sense of taste emerges as producers react to

each other, to the model, and to the garment that she dons. This sui generis social reality

is what Goffman called an interaction order, and through face-to-face encounters, a look

will come to be desired or discarded. Building on the premise of symbolic interactionism

that meanings are collectively worked out in contexts, ethnographers posit that values

belong to situations as much to people (Jerolmack and Khan 2013).

When these tastemakers sense that a look is working, we can observe an

interactional resonance, which McDonnell describes as an energy, a deep reverberation,

24

a mental buzz, the collective nodding of heads (McDonnell 2013, this issue). Resonance

can be observed in interactions between agents and models, between clients, and between

clothing objects, models, and clients. The interactive nature of aesthetic judgment

becomes apparent in the work of international model scouts, who are the initial

gatekeepers to the fashion modeling industry.

Alexey Vasiliev has been scouting for 17 years; when we met in his city of

Moscow, he brought composite cards and dated Polaroid pictures of teenage girls that had

become some of the worlds top models over the years. I spent two summers in the

Western side of Russia following scouts like Alexey as they searched for young women,

typically between the ages of 13 and 20, to present to agencies in Moscow and potentially

abroad.

Scouts, like all good detectives, dont always know where to look until they find

what it is they are looking for (Stark 2009). They deliberately cast the widest net

possible, spreading their attention on the metro and at music festivals, and shopping

malls, and scouring remote villages and town centers all across Siberiaat ten time

zones wide, it takes considerable investments of time and movement for scouts to sort

through fresh faces. It could be on the street, any street, necessitating constant vigilance.

One scout terms this wild scouting, and likens the search for game in the wilderness.

Scouts can also tap into a network of satellite agencies in remote towns and cities, setting

up appointments to meet girls. Finally scouts set up organized model contests in small

towns in attempt to draw out all of the girls in the area, or they go to organized local

beauty contests to search among the contestants. This is what recently brought me to the

Miss Ekaterinburg beauty pageant in Russia, where Alexey was looking for new faces:

25

The afternoon before the pageant competition, Alexey has organized a casting for

all of the contestants, held in a large mirrored room, the kind built for ballet

practice. I sit on the sidelines with my translator, Pasha, himself a former

assistant to organizers of a major model contest in Russia. Alexey stands in the

center of the room, before a line of 18 girls wearing bikinis, having been told to

change from their regular clothes. They step before him, one by one, practiced

and ready to state basic biographical information into his video recorder: Hello,

my name is---. Im --- years old. Im from ---. He pauses the filming to instruct

all of the girls on posing for snapshots: hand on hip, one leg bent at the knee, back

tall and straightshot from the front, sides, and back. The girls laugh and

practice posing together in the mirrored walls. Occasionally Alexey sets his

camera aside, pulls out a measuring tape, and wraps it around some part of a girls

body. Pasha whispers to me, Theres nothing here, as Alexey continues to

carefully teach, photograph, and videotape each girl.

Over the course of the next two days, Alexey would visit the five local modeling agencies

of Ekaterinburg, talking and taping anywhere from five to ten girls in each office, usually

a dimly lit room in a squat office building in the city center. Pasha and Alexey were

silent about their assessment of most of them, and only one time did Pasha whisper to me,

when a girl has finished with pictures and video, She can work. He later explained that

this particular girl was an obvious model: tall and lanky, with a symmetrical face and

proportionate body. Alexey spent a bit more time with particular girls. If he found a face

26

and body that seemed right for fashion, he would then try to make her laugh on tape, or

make a funny face, by offering jokes and riddles. A few girls he asked to dance, and he

pulled up pop tunes on his smartphone while a girl emitted an embarrassed laugh and

proceeded to dance under the gaze of his camera in front of everyone in the room,

including me and my translator Pasha. He kept the casting room fun and seemed to enjoy

engaging the girls. He asked about their lives, their interests, just to see, he explained,

how they interact. For the few young women in whom Alexey sees modeling potential,

his tricks are intended to elicit their personality, he tells me later, so he can show

evidence to agents of her potential. Most scouts agree that they can tell within a few

moments of meeting a girl if they want to take her on, but crucially, they must meet her in

person.

Scouts are in many ways preparing models for the barrage of personality

assessments they are likely to come across as they meet clients. The search for

personality cues manifest in all kinds of tricks of the casting trade: one client explained

how watches models on the elevator security cameras as they change shoes from sneakers

to high-heels, just to see their natural mannerisms and how they carry themselves. At

castings, I came to expect audition sheets soliciting information like hobbies or likes.

At one point during Fashion Week, I filled out the following questions to include on my

composite card for clients: Your perfect night..... Soundtrack of your life...... your

inspiration..... and so on. At one casting, models were asked to fill out a typical

information form including name, age, agency, as well as favorite color, favorite band,

do you play an instrument, and do you like modeling. In this instance, I asked the

casting director what they do with all of this seemingly trivial information, to which she

27

replied: Its just to get a sense of the person, if theyre a good fit with us. Its about a

vibe.

Like the cultural fit between job candidates and interviewers in the hiring

process (Rivera 2013), models are chosen in part because they resonate with taste. This

resonance can be observed as the presence of heightened emotions, and objects can

trigger it (McDonnell 2013, this issue). Objects like clothes have a character or a mood

that clients seek to convey in their choice of models as well. Many show fittings are

called Fit to Confirm, which gives the client the right to release a model if it turns out

that in the final line up of girls and outfits, one body is not fitting with the whole of the

collection.

A spatial and temporal arrangement of things and people can trigger a sense of

excitement or affect (Wissinger 2007) in something so seemingly mundane as a girl

walking in one outfit as opposed to a different girl or different garment. For example, at

one Fashion Week show casting:

I walk in and a young woman is modeling a dress to two older Italian women,

who shower her with praise. I stand against the wall in the cluttered design studio

while they excitedly speak to each other, and to her, and ask her to try on a

multitude of outfits and walk the length of the room and back. Each new outfit

makes them more delighted than the last. They are almost completing each

others sentences: I love her. Everything looks so good on her because she is so

elegant. And Yes, she is perfect, we have to have her, we have to fight to have

her [in our show]! The two women watched with smiles as the young model

28

departed. I am up next. Hello, I say, and stand before them in a vacuum of

sound. They are silent while they look at me with tight smiles. They quickly flip

through my portfolio in silence. Can you walk? I walk the length of the room

down and back, and upon return, my closed book was waiting for me in an

outstretched arm: Thank you Ashley, thank you for coming.

In this instance, the sense of a models appropriateness ricocheted between the two

clients, the model, and the clothing. This flow of energy is situational, and contingent on

the specific configuration of body-personality-garment. One body works while another

one doesnt. When its not working, the excitement lulls in a palpable way. Silence is a

telling form of communication, and in this casting, it was clear to me and to the

designers that I did not fit their collection. I had scribbled in my notebook after the

encounter: Heres the weird thing, they didnt even say anything to each other, its like

everyone in the room just at once agreed silently to not have me try anything on.

Cultural sociology, inspired by research among STS scholars, seeks to document

how objects mediate action, and how interactions between materiality and bodies shape

interpretation (Acord 2010; Griswold et al. 2013). For instance, in her work on

mediation among art curators, Acord documents the subtle ways that artistic knowledge

emerges through interactions between artists, curators, and the art in particular spaces

not just abstract social space like a Bourdieusian field, but in the actual space of a

museum room or a design studio. Art curators, like fashion intermediaries and other

professional tastemakers, arrive at aesthetic decisions by way of sensing this interactional

resonance. Because perception is both material and cognitive, aesthetic deliberation

29

involves the cognitive awareness of what other people want and expect, as well as

interpretations of material things.

While measuring the causal power of physical objects and bodies in interaction

may be beyond the reach of ethnography, participant observation certainly demonstrates

the important role of objects in mediating action and orienting meaning. Ethnography

enables observations of resonance in action, and it captures the salience of emotion in

meaning-making processes.

Ethnographic sight brings into focus those dimensions of incipient taste that are

hinted at in interviews, like the sensory dimensions of personality and its contingent

meaning in an interactions with materials. Personality becomes fleshed out as an

interactional capacity, which makes the look resonate via face-to-face encounters. This

interactive nature captures what sociologists of culture have documented as a shared

sense of craftsmanship among professional collaborators (Becker 1982) or what Eliasoph

and Lichtermann (2003) call group styles that are communicated through interaction.

However, ethnography obscures our vision of status and hierarchy that which network

analysis had neatly mapped out. By keeping the attention on the micro, interactional

components of taste, we have a view of culture as interactive knowledge, bound by an

analytic lens that frames culture within practices.

The Fourth Method: Observant Participation

30

The capacity to identify some girls as really good constitutes a particular way of

seeing, both abstract social space of the field and concrete physical space in situated

interaction. The mechanisms of transmitting this taste may not be observable to

outsiders, but rather felt by insiders. Bourdieu argued that in order to make taste

distinctions, people subconsciously draw from embodied knowledge and habituated

practices, routines, and taken-for-granted competencies, all of which are learned over

time through practice in the body (1984).

To access such acculturation and habituation, sociologists can undertake close

studies of habitus to show how particular ways of knowing and seeing are learned and

embodied, for instance in Desmonds auto-ethnography of firefighting (2007) or

OConnors self-mastery of glass blowing (2005). Every ethnographer tries to get a grasp

on the everyday reality experienced by the people they study. Above and beyond taking

seriously their subjects point of view, some also deploy what Wacquant describes as

an ethnography experiment, in which the researchers body comes to grasp in vivo

through his own flesh and bloodand then reflecting critically on the transformations of

itthe collective construction of the schemata that organize his subjects perception and

values (2009). Beyond participant observation, Wacquant calls this observant

participation or carnal sociology; habitus here is both theory and methodological tool

(2004, p. 6; 2011). Through deep immersion in their field sites, researchers should be

able to pick up and learn these embodied dispositions.

In my own time in the field, I began to develop a carnal knowledge of fashion, so

much so that my gait, my dispositions, and my comfort in my own skin changed to orient

with those of my subjects. I could see changes in the way I read magazines; like bookers,

31

I did less actual reading of them than scanning the images, beginning with the back

editorial spreads, as this is where stylists and models names and agencies are listed. I

saw it in the way I walked, which was something I had long been practicing and studying.

I practiced with training; a catwalk coach spent hours critiquing my walk along with two

other young women, and by the end I had bloodied my Achilles heel in stilettos, but in

just a few months with regular wear, I could slip the shoes off and on as easily as I could

adjust into a fashion walk. Clients frequently ask models to modify how they walk for a

specific show. Like the look, a walk should be both individually unique and flexible to

fit the feel of the collection. At show castings, models are asked to understand and

perform the right gait: this walk is fast and boyish, says one casting director, while

another wants a walk that is very feminine. I started to recognize a good walk in other

models; and I began to see which cadence of gait suited which designers. Day by day, I

was getting the hang of the rules of the game, right into my movements.

This process of bodily restructuration was also evident in my changing

relationship to clothing, another site for the materiality of objects to mediate meaning.

On casting days, and even days when I was off from work, I agonized over what to wear.

The clothing should be edgy, like my look, but it should convey traits of my personality

as well, and above all it should make me look thin like a model. When wearing clothing

that did not work on these levels, I felt inadequate, and was more likely to think that

others saw me this way as well:

Walking into my agency today, Im anxious. Im wearing tight jeans that arent

the most flattering, actually its uncomfortable. My booker gives me two quick

32

glances down my body and says nothing, no compliment of my style like she

sometimes offers. Its the smallest of gestures but I recognize it and it stings.

Perhaps shes even done it deliberately to signal something to me.

Here the observant participants measurement tools are self-reflexive field notes, which

measure a distance of researchers former and current self and body. I could sense better

and better with each casting if I fit with the field and with the clients felt sense for the

right looks, because I could feel it too.

Taking on the dispositions of scouts, bookers, and clients proved more difficult.

When scouting with scouts, I can usually predict their choices in a casting room full of

contenders. I am rarely surprised by their choices, even if an edgy skinny teenage look

grows further away from the kinds of people I see on a day-to-day basis. I can make

evaluations fairly quickly among a pile of similar-looking girls. However, I cannot tell

you precisely how I do this. My own habitus was changing throughout my time in the

field in ways I could recognize, if not operationalize. If asked, But, Ashley, how do you

know, I would return full circle to the beginnings of this essay, and reply: I just know.

Proclamations of intuition like, I know it when I see it, capture little underlying

motivation, but such statements are completely honest as phenomenological descriptions

of processes of judgment (Vaisey 2009, p. 1695). Researches can tap into and share in

the production of meanings through observant participation, emphasizing culture as

embodied and tacit knowledge. Tacit understandings are accrued through practice, and

through experience, we arrive at cultural meanings.

33

Conclusions

The problem of arriving upon incipient taste among cultural producersand

fashion producers in particularcan be answered in multiple ways, and each method sets

a frame around how researchers see culture. Methods are a type of optical device in that

they shape our ways of knowing and understanding the social world.

Interviews provide narrative accounts of what people do and why, but in these

accounts, people offer post-hoc justifications for action, which may be misrecognized as

internalized schemas, thus we mistake rationalizations for motivations (Vaisey 2009).

Partly this is because knowledge is far from coherent, and we move through a world of

meaning that rarely makes one sense. Articulating why one knows something may be an

unreasonable demand to make in an interview. Furthermore, this research finds that in

interviews, people also talk over the interactional aspects of their work, misrecognizing

collective processes as individual talent. Rather than assume such contradictions are a

measurement problem, we can take them as observations in themselves. By providing a

forum for tastemakers to confirm the strength of their eyes and signal their professional

competence, interviews tell us what people value and what they want to like, and not like.

While interviews suggest taste emerges from a set of internalized norms and

personal capacities, network analysis frames taste along status hierarchies and

information exchange. Network analysis accounts for how taste structured in a field,

based on mechanisms that can be verified in the interviews, like the importance of seeing

the field with options mechanisms. With a macro picture of the field, however, we miss

34

the nuance of what happens in face-to-face meetings, so crucial for clients and agents to

size up models. An empirical strength of ethnography is to access situated behavior to

see how people actually behave (Jerolmack and Khan 2013). Ethnography allows for the

interpretive contingency of situations, and each casting opens a new set of possible

arrangements of bodies, personalities, and garments, and this choreography of action is

something ethnographers can observe in practice (Griswold et al. 2013).

Carnal ethnography can further describe the development of the fashion habitus.

While carnal ethnography exposes researchers to practical and prediscursive embodied

sense, they may find themselves arriving at that familiar inability to articulate how it

works. By turning their bodies into the field, researchers can tell us that meaning comes

from corporeality and materiality (OConnor 2005). This is yet one more partial account

that can and should be offered alongside others.

Having an eye for the future of fashion is simultaneously an act of seeing and of

understanding a field at the macro levela whole system aesthetic possibilities and status

hierarchies in fashionand at the micro level, in the interactional and corporeal sense of

resonance. From interviews to network analysis to ethnography and auto-ethnography,

we come full circle to the puzzle of incipient taste, which is, I concede, here only

partially and cautiously answered. Across each method, new ambiguities emerge: how

do we measure personality, or habitus, or resonance? These things do not lend

themselves to easy operationalization or even articulation, yet they are central to the

problem at hand. Each of these different methods, as an optical device, gives the

researcher a particular and complementary window to examine taste, and by extension,

each method renders a certain way to see culture.

35

Acknowledgements: Thanks to John Mohr and Amin Ghaziani for organizing the

Measuring Culture Conference at the University of British Columbia in October 2012,

and to all of the enthusiastic participants. Thanks to Frederic Godart, Thomas Franssen,

Terrence McDonnell, Japonica Brown-Saracino, Iddo Tavory, and Alex van Venrooij for

valuable comments on previous drafts of this paper.

REFERENCES

Acord, S. (2010). Beyond the head: The practical work of curating contemporary art.

Qualitative Sociology 33, 447467.

Aspers, P. (2009). Knowledge and valuation in markets. Theory & Society 38:111131.

Aspers, P. & Godart, F. (2013). Sociology of fashion: Order and change. Annual Review

of Sociology 39, 171-192.

Becker, H. S. (1982). Art worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Beckert, J. & Aspers, P, eds. (2011). The worth of goods: Valuation and pricing in the

economy. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Benzecry, C., & Krause, M. (2010). How do they know? Practicing knowledge in

comparative perspective. Qualitative Sociology 33, 415422.

Bielby, W. T., & Bielby, D. D. (1994). All Hits Are Flukes - Institutionalized DecisionMaking and the Rhetoric of Network Prime-Time Program-Development,

American Journal of Sociology, 99(5), 1287-1313.

36

Blumer, H. (1937). Social psychology. In E P. Schmidt (Ed.), Man and Society (pp. 144

98). New York: Prentice-Hall.

_____. (1969). Fashion: From class differentiation to collective selection. Sociological

Quarterly 10:275-291.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press.

_____. (1990). The logic of practice. trans. Richard Nice. Cambridge, England: Polity

Press.

_____. ([1992] 1996). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field.

Cambridge: Polity Press.

_____. (1993). The field of cultural production: essays on art and literature. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Desmond, M. (2007). On the fireline: Living and dying with wildland firefighters.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Elias, N. (1994 [1939]). The civilizing process: The history of manners and state

formation and civilization. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Eliasoph, N., & Lichterman, P. (2003). Culture in interaction. American Journal of

Sociology 108, 735-94.

Entwistle, J. (2009). The Asethetic economy of fashion: Markets and value in clothing

and modelling. Oxford: Berg.

Ghaziani, A. (2009). An amorphous mist? The problem of measurement in the study

of culture. Theory and Society 38, 581612.

37

Godart, F. (2012). Trend networks: Multidimensional proximity and the formation of

aesthetic choices in the creative economy. Regional Studies, doi:

10.1080/00343404.2012.732693.

Godart, F., Mears, A. (2009). How do cultural Producers make creative decisions?

Lessons from the catwalk. Social Forces 88(2), 671-692.

Godart, F., Shipilov, A., & Claes, K. (2013). Making the most of the revolving door: The

impact of outward personnel mobility networks on organizational creativity.

Organization Science, doi:10.1287/orsc.2013.0839.

Grenfell, M., Hardy, C. (2003). Field maneuvers: Bourdieu and the young British artists.

Space & Culture 6(1), 19-34.

Griswold, W. (1986). Renaissance revivals: City comedy and revenge tragedy in the

London Theatre 15761980. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fine, G. A. (1992). The culture of production: Aesthetic choices and constraints in

culinary work. American Journal of Sociology 97, 1268-1294.

Frank, R. H., & Cook, P. J. (1995). The winner-take-all society: How more and more

Americans compete for ever fewer and bigger prizes, encouraging economic

waste, income inequality, and an impoverished cultural life. New York: Free

Press.

Jerolmack, C., & Khan, S. (2013). Talk is cheap: Ethnography and the attitudinal

Fallacy. Sociological Methods and Research. Forthcoming December.

Karpik, L. (2010). Valuing the unique. The economics of singularities. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

38

Lamont, M. (2012). Toward a comparative sociology of valuation and evaluation.

Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 20121.

Lamont, M., & Molnar, V. (2002). The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual

Review Sociology. 28:16795.

McDonnell, T. (2013). Drawing out culture: Productive methods to measure cognition

and resonance this issue. Theory & Society. This issue.

Griswold, W., Mangione, G., & McDonnell, T. E. (2013). Objects, words, and bodies in

space: Bringing materiality into cultural analysis. Qualitative Sociology

forthcoming December.

OConnor, E. (2005). Embodied knowledge: The experience of meaning and the struggle

towards proficiency in glassblowing. Ethnography 6(2): 183204.

Pachucki, M., Breiger, R. (2010). Cultural holes: beyond relationality in social networks

and culture. Annual Review of Sociology 36, 205-224.

Podolny, J. M. (2005). Status signals: a sociological study of market competition.

Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Pugh, A. J. (2013). What good are interviews for thinking about culture? Demystifying

interpretive analysis. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1, 42-68.

Sadre-Orafai, S. (2008). Developing images: Race, language, and perception in fashion

model casting. In: Shinkle E (ed.) Fashion as photograph: Viewing and reviewing

fashion images. London: IB Tauris, pp. 141153.

Salganik, M. J., Dodds, P. S., & Watts, D. J. (2006). Experimental study of inequality and

unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. Science 311, 854-856.

Simmel, G. (1957). Fashion. American Journal of Sociology 62, 541-558.

39

Stark, D. (2009). The sense of dissonance: Accounts of worth in economic life.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Vaisey, S. (2009). Motivation and justification: A dual-process model of culture in

action. American Journal of Sociology 114(6), 16751715.

Veblen, T. (2007 [1899]). The theory of the leisure class: An economic study of

institutions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wacquant, L. J. D. (2004). Body & soul: Notebooks of an apprentice boxer. Oxford and

New York: Oxford University Press.

____. (2011). Habitus as topic and tool: Reflections on becoming a prizefighter.

Qualitative Research in Psychology 8, 8192.

Wissinger, E. (2007). Modelling a way of life: Immaterial and affective labour in the

fashion modelling industry. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 7,

250 69.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Man As God Created Him, ThemDokument3 SeitenMan As God Created Him, ThemBOEN YATORNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - 2020-CAP Surveys CatalogDokument356 Seiten1 - 2020-CAP Surveys CatalogCristiane AokiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canoe Matlab 001Dokument58 SeitenCanoe Matlab 001Coolboy RoadsterNoch keine Bewertungen

- MMS - IMCOST (RANJAN) Managing Early Growth of Business and New Venture ExpansionDokument13 SeitenMMS - IMCOST (RANJAN) Managing Early Growth of Business and New Venture ExpansionDhananjay Parshuram SawantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gas Dynamics and Jet Propulsion 2marksDokument15 SeitenGas Dynamics and Jet Propulsion 2marksAbdul rahumanNoch keine Bewertungen

- What's New in CAESAR II: Piping and Equipment CodesDokument1 SeiteWhat's New in CAESAR II: Piping and Equipment CodeslnacerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design of Penstock: Reference Code:IS 11639 (Part 2)Dokument4 SeitenDesign of Penstock: Reference Code:IS 11639 (Part 2)sunchitk100% (3)

- WAQF Podium Design Presentation 16 April 2018Dokument23 SeitenWAQF Podium Design Presentation 16 April 2018hoodqy99Noch keine Bewertungen

- SweetenersDokument23 SeitenSweetenersNur AfifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISO 27001 Introduction Course (05 IT01)Dokument56 SeitenISO 27001 Introduction Course (05 IT01)Sheik MohaideenNoch keine Bewertungen

- JIS G 3141: Cold-Reduced Carbon Steel Sheet and StripDokument6 SeitenJIS G 3141: Cold-Reduced Carbon Steel Sheet and StripHari0% (2)

- (1921) Manual of Work Garment Manufacture: How To Improve Quality and Reduce CostsDokument102 Seiten(1921) Manual of Work Garment Manufacture: How To Improve Quality and Reduce CostsHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

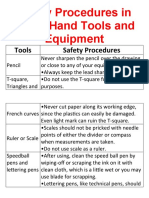

- Safety Procedures in Using Hand Tools and EquipmentDokument12 SeitenSafety Procedures in Using Hand Tools and EquipmentJan IcejimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Out PDFDokument211 SeitenOut PDFAbraham RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Continue Practice Exam Test Questions Part 1 of The SeriesDokument7 SeitenContinue Practice Exam Test Questions Part 1 of The SeriesKenn Earl Bringino VillanuevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winter CrocFest 2017 at St. Augustine Alligator Farm - Final ReportDokument6 SeitenWinter CrocFest 2017 at St. Augustine Alligator Farm - Final ReportColette AdamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevention of Waterborne DiseasesDokument2 SeitenPrevention of Waterborne DiseasesRixin JamtshoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of Irish Monks On Merovingian Diocesan Organization-Robbins BittermannDokument15 SeitenThe Influence of Irish Monks On Merovingian Diocesan Organization-Robbins BittermanngeorgiescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catify To Satisfy - Simple Solutions For Creating A Cat-Friendly Home (PDFDrive)Dokument315 SeitenCatify To Satisfy - Simple Solutions For Creating A Cat-Friendly Home (PDFDrive)Paz Libros100% (2)

- Health Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyDokument3 SeitenHealth Post - Exploring The Intersection of Work and Well-Being - A Guide To Occupational Health PsychologyihealthmailboxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Where We Are in Place and Time "We Are Part of The Universe and Feel Compelled To Explore It."Dokument1 SeiteWhere We Are in Place and Time "We Are Part of The Universe and Feel Compelled To Explore It."Safia-umm Suhaim- FareedNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Flight Fuel Management and Declaring MINIMUM MAYDAY FUEL-1.0Dokument21 SeitenIn Flight Fuel Management and Declaring MINIMUM MAYDAY FUEL-1.0dahiya1988Noch keine Bewertungen

- MultiLoadII Mobile Quick Start PDFDokument10 SeitenMultiLoadII Mobile Quick Start PDFAndrés ColmenaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disassembly Procedures: 1 DELL U2422HB - U2422HXBDokument6 SeitenDisassembly Procedures: 1 DELL U2422HB - U2422HXBIonela CristinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apple Change ManagementDokument31 SeitenApple Change ManagementimuffysNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomy of the pulp cavity กย 2562-1Dokument84 SeitenAnatomy of the pulp cavity กย 2562-1IlincaVasilescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heimbach - Keeping Formingfabrics CleanDokument4 SeitenHeimbach - Keeping Formingfabrics CleanTunç TürkNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Annotated Bibliography of Timothy LearyDokument312 SeitenAn Annotated Bibliography of Timothy LearyGeetika CnNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Are The Spacer Bars in RC Beams - QuoraDokument3 SeitenWhat Are The Spacer Bars in RC Beams - QuoradesignNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pidsdps 2106Dokument174 SeitenPidsdps 2106Steven Claude TanangunanNoch keine Bewertungen