Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Native Medicinal Plants

Hochgeladen von

Andrea UbazCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Native Medicinal Plants

Hochgeladen von

Andrea UbazCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

DOI 10.1007/s10661-009-0899-4

Influence of Brazilian herbal regulations on the use

and conservation of native medicinal plants

Maria G. L. Brando Gustavo P. Cosenza

Accia M. Stanislau Geraldo W. Fernandes

Received: 21 September 2008 / Accepted: 13 March 2009 / Published online: 8 April 2009

Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2009

Abstract For decades, several native medicinal

species have been used by the pharmaceutical

industry in Brazil to create commercial products.

In 1995, the Ministry of Health, following the recommendations of the World Health Organization,

established herbal regulations (RDC 17) in order

to improve the quality of such products. In fact,

only plant species with conclusive results from

pharmacological and toxicological studies can be

used for creating medicines. In this study, we evaluated the consequences of RDC 17 on the use and

conservation of native medicinal plants by comparing the plant material used by six companies in

1995/1996 and 10 years later (2005/2006). Eightythree different species were used in 1995/1996, 50

of them native (60.2%), 16 exotic (19.3%), and 17

imported (20.5%). In 2005/2006, 44 species were

used by the companies and only 19 (43.2%) were

native. The category of plant material that saw the

largest decrease in use was roots, and in 2005/2006

leaves were more used. The study shows a strong

reduction in the collection of native species signalizing the importance of herbal regulations on

their conservation. It also points to the need for

pharmacological and toxicological studies of the

Brazilian native medicinal flora, as well as studies

on their ecology and conservation.

M. G. L. Brando (B)

DATAPLAMTMuseu de Histria Natural e Jardim

Botnico, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais,

31270-901 Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

e-mail: mbrandao@ufmg.br

Introduction

M. G. L. Brando G. P. Cosenza A. M. Stanislau

Laboratrio de Farmacognosia,

Faculdade de Farmcia, Universidade Federal de

Minas Gerais, 31270-901 Belo Horizonte,

Minas Gerais, Brazil

G. W. Fernandes

Departamento de Ecologia Evolutiva &

Biodiversidade, Instituto de Cincias Biolgicas,

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais,

31270-901 Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Keywords Brazilian medicinal plants

Herbal regulation Conservation

Owing to an astonishing mega-diversity, the

Brazilian flora represents one of the worlds richest sources of material for pharmacological use.

Historical records demonstrate that Amerindians

already used native species such as avocado

(Persea americana), wild potatoes (Ipomoea

batatas), mate (Ilex paraguaryensis), and cacao

(Theobroma cacao) thousand of years before the

invasion of the continent by Europeans (Wolters

1992). Despite the wide flora and current intellectual development, Latin American countries,

including Brazil, are involved in the international

370

pharmaceutical market only as suppliers of raw

botanical material. Pilocarpine from the leaves of

Jaborandi (Pilocarpus species, Rutaceae), alphabisabolol, taken from candeia wood (Eremanthus

erythropappus (DC.) MacLeish, Asteraceae), or

rutine, obtained from favela fruits (Dimorphandra mollis Benth., Fabaceae), are examples of

natural compounds obtained from Brazilian native plants that are almost exclusively used by

international pharmaceutical corporations (www.

chinachemnet.com, www.merck.com).

Currently, medicinal plants are widely used

as home remedies by both rural and urban inhabitants of Brazil, a consequence of the high

cost of industrialized medicine. However, the intense mixture of cultures (Native, African, and

European) during the last several centuries has

led to a progressive substitution from native medicinal plants to other species from elsewhere in

Latin America (Dean 1996). The accelerating destruction of Brazils botanically rich native ecosystems has also contributed to a gradual loss of

knowledge about native plants used in traditional

medicine, including those found in areas of the

Atlantic Forest and the Amazon where accelerated occupation takes place (Amorozo 2002;

Begossi et al. 2002; Brando et al. 2004; Di Stasi

and Hiruma-Lima 2002; Shanley and Luz 2003;

Shanley and Rosa 2005). The negative perspective

on conservation of native species in some places

of Brazil highlights the urgent need to recover

information on uses of native plant species and to

promote studies on their ecology and conservation

(Giulietti et al. 2005; Michalski et al. 2008).

For decades, several native medicinal species

have been used by pharmaceutical companies in

Brazil to create commercial products. These companies are represented by small laboratories that

evaluate their products on the basis of traditional

formulas (Ferreira 1998; Fernandes 2004). However, very often, the efficacy and safety of these

products are not measured and they might not

meet the minimal standard, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for products

for traditional use (WHO 1993, 1998). In 1995, the

Ministry of Health, following the recommendations of World Health Organization, established

herbal regulations (RDC 17) in order to improve

the quality of commercial herbal products. Ac-

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

cording to these rules, the complete acceptance

of an herbal medicine by Brazilian governmental

agencies can occur only after the efficacy and

safety of the product has been scientifically determined (Carvalho et al. 2008; Calixto 2000; Rates

2001). Some effort has been made by the companies to develop standardized phytomedicines

from native species with proof of quality, safety,

and efficacy, but only a few examples of success

can be mentioned. Acheflan is produced with

an essential oil obtained from Cordia verbenaceae,

a native species used in traditional medicine to

treat inflammations (Calixto 2005). In the present

study, we present a list of Brazilian native medicinal plants used by certain pharmaceutical companies of Minas Gerais to make the traditional

commercial formulas in 1995/1996 and 10 years

after the publication of RDC 17 and discuss the

influence of these herbal regulations on the use

and conservation of native medicinal plants.

Materials and methods

This study was performed through a comparison

of the native medicinal plants used by six pharmaceutical companies of Minas Gerais in 1995/1996

and 10 years after the establishment of the first

Brazilian herbal regulation, RDC 17 (Brasil 1995).

We studied the plants used by Indstria Farmacutica Catedral, Laboratrio Belm Jardim, Laboratrio Rodomonte, Laboratrio Globo, Copo

Medicinal Indstria, and Comrcio and Laboratrio Magaraz, located in the Southwest State

of Minas Gerais. Data about the plants currently

used in other parts of Brazil were verified on

the website of the Brazilian Regulatory Agency,

ANVISA (www.anvisa.gov.br).

After the identification of the botanical materials, the species were divided into three different

groups based on their distribution and use: species

originally found in the Americas were termed native species, those that have their origin in other

parts of the world were termed exotic species,

and species imported directly to extract the active

principals were termed imported species. The

numbers of species used during the two periods

in each category are listed in Table 1. Names of

the species used, parts used in the preparation

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

371

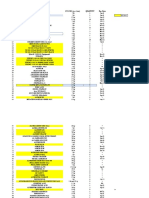

Table 1 Number (%) of species used by the pharmaceutical companies in Minas Gerais in the two studied periods

Origin

1995/1996

2005/2006

Native

Exotic

Imported

Total

50 (60.2)

16 (19.3)

17 (20.5)

83 (100)

19 (43.2)

12 (27.3)

13 (29.5)

44 (100)

of the remedies, and the number of companies

that have products prepared with that species are

given in Table 2. Table 3 shows the quantities of

the different plant organs used in 1995/1996 and

10 years later, in 2005/2006.

Plants used in 19951996

Data about the plants used in 1995/1996 as well

as botanical material used in the preparation of

the commercial products were furnished by the

companies. They provided the popular and scientific names, botanical families, parts of the plant

Table 2 Native medicinal plants and number of pharmaceutical companies which used them in 1995/1996 and 2005/2006

(n = 6) in Minas Gerais and in others parts of Brazil in 2008 (n = 22)

Family/species

Alismataceae

Echinodorus macrophyllus (Kunth) Michelia,b

Anacardiaceae

Anacardium occidentale L.a,b,c

Apocynaceae

Geissospermum laeve (Vell.) Miersa,c

Macrosiphonia velame (A.St-Hil.) Mll.Arg.c

Plumeria lancifolia Mll. Argoviensisa

Asteraceae

Baccharis trimera (Less.) DCa,b,c,d

Lychnophora sp. Mart.c

Mikania glomerata Sprengela,b,d,e

Mikania hirsutissima DC.a,b

Vernonia polyanthes Less.b,c

Bignoniaceae

Anemopaegma mirandum (Cham.) Mart.exDCa,b

Jacaranda caroba (Vell.) DC.a,c

Tabebuia avellanedae Lorentz ex Griseb.b

Tynnanthus fasciculatus (Vell.) Miersa,b

Celastraceae

Maytenus ilicifolia (Schrad.) Planch.b,d,e

Convolvulaceae

Operculina macrocarpa L.a

Cucurbitaceae

Cayaponia sp.a,b,c

Euphorbiaceae

Phyllanthus niruri L./Phyllanthus tenellus Roxb.d

Fabaceae

Bauhinia forficata Linkc

Bowdichia virgilioides Kuntha,c

Copaifera sp. L.a,c

Erythrina mulungu Martius ex Benth.a,b,c,d

Hymenaea courbaril L.b,c

Senna occidentalis (L.) Linka,c

Lauraceae

Ocotea sassafras (Meisn.) Meza

Persea sp.a

Popular names

Parts

Minas Gerais

1995/1996 2005/2006

Brazil

Sep 2008

Chapu de Couro

Lvs

Cajueiro

Bark

Pau Pereira

Velame do campo

Agoniada

Bark

Lvs

Bark

5

5

5

0

0

0

0

0

1

Carqueja amarga

Arnica da Serra

Guaco

Cip Cabeludo

Assa Peixe

Wpl

Aerial

Lvs

Lvs

Lvs

4

3

3

5

3

4

0

5

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

Catuaba/Catuiba

Caroba/Carobinha/

Ip Roxo

Cip Cravo

Rtz

Lvs

Bark

Stm

5

5

4

5

3

3

0

0

0

0

0

0

Espinheira Santa

Lvs

Jalapa do Brasil

Rts

Taiui

Rts

Quebra-Pedra

Wpl

Pata de Vaca

Sucupira

Copaba

Mulungu

Jatob

Fedegoso

Lvs

Sed

Balsam

Bark

Fruits

Rts

5

5

0

4

2

4

0

0

3

2

0

0

0

0

0

2

1

0

Canela Sassafrs

Abacateiro

Bark

Lvs

2

6

0

3

0

1

372

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

Table 2 (continued)

Family/species

Popular names

Parts

Minas Gerais

1995/1996 2005/2006

Lecythidaceae

Cariniana brasiliensis Casarettoa

Jequitib

Bark 3

0

Liliaceae

Herreria salsaparilha Mart.c

Salsaparrilha

Rts

5

0

Malvaceae

Algodoeiro

Lvs

5

0

Gossypium herbaceum L.a,c

Menispermaceae

Chondodendron platyphylla (A.St-Hil.)Miersa,b,c

Abtua

Bark 5

2

Mimosaceae

Anadenanthera colubrina (Vell.) Brenan

Angico

Lvs

6

0

Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Covillea,c,d

Barbatimo

Bark 6

0

Monimiaceae

Siparuna apiosyce (Mart. ex Tul.) DC.a

Limoeiro Bravo

Lvs

2

0

Moraceae

Brosimum gaudichaudii Trculc

Mamacadela

Rts

5

0

Myrtaceae

Stenocalyx pitanga O. Berg

Pitanga

Lvs

3

0

Olacaceae

Ptychopetalum olacoides Bent.a,b

Muirapuama

Rts

5

0

Passifloraceae

Passiflora sp.a,b,c,e

Maracuj

Lvs

6

5

Piperaceae

Pothomorphe umbellata (L.) Miq.a,b,c

Pariparoba/Caapeba Rts

5

2

Polygonaceae

Polygonum hydropiperoides Michxc

Erva de Bicho

Rts

6

3

Rubiaceae

Psychotria ipecacuanha (Brot.) Stokes;

Ipecacuanha

Rts

6

1

Psychotria acuminata Benth.a,b,c,d

Remijia ferruginea (A.St-Hil) DC.a,c

Quina Mineira

Bark 4

4

Rudgea viburnoides (Cham.) Benth.

Congonha

Lvs

5

0

Rutaceae

Pilocarpus jaborandi Holmes; Pilocarpus microphyllus Jaborandi

Lvs

6

5

Stapf ex Wardl.a,b,d

Sapindaceae

Paullinia cupana Kuntha,b,d,e

Guaran

Sed

5

5

Simaroubaceae

Picrasma sp.a

Qussia

Bark 2

2

Simaruba sp.a,c

Simaruba

Bark 3

0

Smilacaceae

Smilax japicanga Griseb.a,b,c

Japecanga

Rts

3

3

Solanaceae

Solanum paniculatum L.a,b

Jurubeba

Rts

6

4

Sterculiaceae

Waltheria douradinha St-Hila,c

Douradinha

Lvs

4

0

Violaceae

Anchietea salutaris A. St-Hil.a,b,c

Cip Suma

Rts

5

0

a Species described in the Brazilian Official Pharmacopoeia first edition

b Species in products commercialized in pharmacies of Recife (Melo et al. 2008)

c Species mentioned by naturalists in Minas Gerais in the nineteenth century (Brando et al. 2008a, b)

d Species described in the Brazilian Official Pharmacopoeia fourth edition

e Species included in RDC 48 (2004)

Brazil

Sep 2008

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

10

0

2

1

1

0

0

3

0

0

0

1

0

0

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

373

Table 3 Approximate quantities of different plant parts

of native species used by the companies in 1995/1996 and

2005/2006 (100 kg approximately)

Parts

Balsam

Fruits

Leaves

Roots

Seeds

Whole plant

Wood

1995/1996

0

5

51

67

5

5

39

2005/2006

3

0

26

16

5

4

12

used for preparation of products, and the name

and address of each supplier. Species identification was complemented by a set of pharmaceutical

analyses of identity used in the quality control

of herbal drugs and recommended by Pharmacopoeias (FBRAS) and WHO (1998). They are

based on botanical (organoleptic, macroscopic,

and microscopic) and chemical characterization (chromatographic methods; Brando 1996).

Botanical characterization was complemented by

a specific bibliography on the analysis of the herbal drug (Gilg et al. 1942; Youngken 1943; Golse

1955; Casamada 1977; Deutschmann et al. 1984;

Eschricher 1988; Langhammer 1989; Oliveira

et al. 1991) as well as a chemical characterization

(Wagner and Bladt 1996). The achieved results

were also compared with standard plant species

from a databank of herbal materials of the Federal

University of Minas Gerais (DATAPLAMT). In

DATAPLAMT, it is possible to find detailed morphological, anatomical, and chemical descriptions

of several medicinal species, as well as standard

samples of the plants, which can be used to identify other samples (www.dataplamt.org.br). These

analyses were important because in 1995/1996 the

correct identification of plant materials was not

required of the companies and the substitution of

plants for other species, as well as the adulteration

of the products, was frequent.

The botanical samples were composed of dried

seeds, flowers, fruits, leaves, roots, and rhizomes in different forms (cut, broken, or pulverized). Many samples such as pulverized seeds of

Paullinia cupana, aerial parts of Baccharis trimera,

or leaves of Mikania hirsutissima were very easy

to identify by the mentioned methods since they

have their own morphological and chemical char-

acteristics. On the other hand, species of Passiflora, Cayaponia, Simaruba, or Picrasma were

impossible to identify because their botanical and

chemical profiles are very similar. There is no

doubt of the importance of voucher herbarium

samples for the correct identification of botanical

materials. However, collecting usable herbarium

samples in commerce or industry is very difficult

since in almost all cases the vendors are not the

collectors of the plants (Albuquerque et al. 2007;

Melo et al. 2008). The performed pharmaceutical

analyses were very helpful for the identification

of the plant material. However, the possibility of

an inaccurate identification of the species must be

considered since it can introduce bias in our work.

Plants used in 2005/2006

Data about the species used in this period were

obtained directly from the companies or their

websites. Species identification was based only on

the scientific names of the plants furnished by

the companies or found on the internet since in

2005/2006 the correct identification of the plants

was a requirement of ANVISA.

Results

A total of 226 samples of botanical material were

analyzed in 1995/1996 and 172 (76.1%) were identified by the botanical and chemical methods.

Fifty-four samples do not correspond to any descriptions or similarity in both the bibliography

and standard samples and were excluded from

the study. The six laboratories used 83 different

plant species for preparing their commercial products, 50 of them (60.2%) native of America, 16

(19.3%) exotic, and 17 (20.5%) imported species.

The number of species used in 2005/2006 was

drastically reduced to 44 and only 19 (43.2%) are

native to Brazil, as shown in Table 1. Despite the

reduction in the number of exotic species used

in 2005/2006 (12 species) compared to 1995/1996

(16 species), the proportion increased from 19.3%

in 1995/1996 to 27.3% in 2005/2006. The same

trend was observed with the imported species

that the number of species used decreased from

374

1995/1996 to 2005/2006 while the proportion increased (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the families, scientific and

popular names, and parts used of 83 species

and the number of companies that used these

species during the two studied periods. The most

frequently used species in 1995/1996 were

Anadenanthera colubrina (Vell.) Brenan and

Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Coville

(Mimosaceae), Persea sp. (Lauraceae), Passiflora

sp. (Passifloraceae), Polygonum hydropiperoides

Michx (Polygonaceae), Psychotria ipecacuanha

(Brot.) Stokes and P. acuminata Benth.

(Rubiaceae), Pilocarpus sp. (Rutaceae), and

Solanum paniculatum L. (Solanaceae), being

used by all six companies. In 2005/2006, fewer

companies used these plants and none of

them used A. colubrina (Vell.) Brenan and S.

adstringens (Mart.) Coville (Mimosaceae) in

their products. There were 21 other species that

were used by five companies in 1995/1996, but

from these only five (Anemopaegma mirandum

(Cham.) Mart. ex DC and Jacaranda caroba

(Vell.) DC., Chondodendron platyphylla (A.StHil.) Miers, Pothomorphe umbellata (L.) Miq.,

and P. cupana Kunth) were still in use in

2005/2006.

Thirty-eight species used in 1995/1996 were described in the first edition of FBRAS as being important in conventional medicine (Brando et al.

2006, 2008a). Twenty-eight others were also mentioned by European naturalists in the nineteenth

century (Brando et al. 2008b) showing their long

tradition of use as confirmed by the historical

record. In 2005/2006, most of these species were

no longer used by the companies. On the other

hand, products from six exotic and five imported

species began to be made. Copaiba Balsam was

the only native plant used in the production of

new products. The number of exotic and imported

species used in 2005/2006 by companies in other

parts of Brazil is also higher than the number of

native species used.

Table 3 shows that 14 suppliers of different

Brazilian states (Minas Gerais = 4, So Paulo =

9, Rio de Janeiro = 2, Paran = 1, Bahia = 1,

Amazonas = 1) supplied the plants in 1995/1996.

The four suppliers of Minas Gerais were

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

raizeiros, people that collect wild plants commercialized for use directly by the companies.

Several organs of the plants were used both in

1995/1996 and 2005/2006. The highest drop in use

of plant organs in 1995/1996 was for roots (13

different species) while in 2005/2006 it was leaves

(11 species). The quantity of roots used in 1996

was approximately 6,700 kg, while in 2005/2006 it

was reduced to approximately one fourth of that

(Table 3). In the same period, the use of wood

fell by two thirds, from approximately 3,900 to

1,200 kg. The quantity of leaves used has also

suffered, seeing a reduction of 50% falling from

approximately 5,100 kg in 1995/1996 to 2,600 kg

in 2005/2006.

Discussion and conclusion

The Traditional Medicine Division of WHO

recognizes the therapeutic potential of traditional

plant remedies and recommends that their efficacies be evaluated through pharmacological and

toxicological studies (WHO 2002). Traditional

formulas prepared with Brazilian native medicinal

plants were widely used by local pharmaceutical

companies in commercial products (Ferreira 1998;

Fernandes 2004). In 1995, the Brazilian Health

Ministry established herbal regulations (RDC 17)

in order to improve the quality of such products

(Brasil 1995). In this study, we observed a strong

reduction in the use of the native medicinal plants

by the pharmaceutical companies since the establishment of RDC 17. In 1995/1996, 83 plant

species, 50 of them native (60.2%), were used

by certain pharmaceutical companies of Minas

Gerais. This is a significant number since it was

thought that, in the 1990s, in all of Brazil, the companies used approximately 90 different species

(Calixto 2000; Rates 2001). It can be pointed out

that this high number of species is a consequence

of cultural and geographic aspects of Minas Gerais

which is still rich in cultural aspects correlated

with medicinal plants. In 2005/2006, only 44 plant

species, 19 of them native (43.2%), were used by

the companies, showing a strong reduction in the

preparation of herbal medicines.

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

The traditional use of many species used in

1995/1996 was already described by European naturalists in the nineteenth century (Table 2) and

they must be regarded as a priority for pharmacological studies, as they have long tradition of

use confirmed by the historical record (Brando

et al. 2008b). Species such as J. caroba (Vell.)

DC., P. umbellata (L.) Miq.,P. hydropiperoides

Michx, Remijia ferruginea (A.St-Hil) DC., or Smilax japicanga Griseb., for example, despite being

used by companies in 2005/2006, will soon be

removed from the market because they do not

have enough results to demonstrate their efficacy

and safety and cannot be approved by ANVISA.

The same will happen to the 78 species recently

listed by Melo et al. (2008) used in pharmaceutical products sold in pharmacies of Recife, a city

situated in northwest of Brazil. From the listed

species, 23 were used by the companies of Minas

Gerais in 1995/1996 but only five (Mikania glomerata Sprengel, J. caroba (Vell.) DC., Erythrina

mulungu Martius ex Benth., Passiflora sp.,andP.

cupana Kunth) are registered with the Regulatory

Agency (ANVISA). This fact highlights a disturbing situation, where foreign chemical pharmaceutical companies that produce medicines with

species from their own country will be favored

in the market while the national industry will be

forced to start producing medicines with exotic or

imported species. We argue that the native plant

species already used by the national industry and

that were listed in the first edition of Brazilian

Pharmacopoeia must be submitted urgently to

pharmacological and toxicological studies and reconsidered by the Brazilian Health Ministry. If the

trend for the use of exotic and imported species in

the formulation of new medicines persists, we will

lose traditional and scientific information on the

pharmaceutical properties of many native species.

Therefore, we suggest that a strong debate by the

scientific public and policy makers should take

place in an attempt to improve and facilitate the

pharmacological study of the native flora.

It is clear that there is not enough knowledge,

both among the population and within the scientific community, of the pharmacological properties of the Brazilian native plant species. In fact,

a much wider and diverse use of medicinal herbs

375

should be encouraged with the immense richness

of Brazilian flora. Some effort has been made by

the companies towards the development of standardized phytomedicines with native species, with

proof of quality, safety, and efficacy. One trend

observed in our study is a clear substitution from

the use of native species to exotic and imported

species. The species Foeniculum vulgaris, Panax

ginseng, Matricharia recutita, Ginkgo biloba,

Hypericum perforatum, Melissa officinalis, Aloe

barbadensis, Valeriana officinalis, and Zingiber officinalis, for example, were not used in 1995/1996

while in 2005/2006 the six companies have products made from them. The recent use of these and

21 other exotic and imported species by Brazilian

pharmaceutical companies is a consequence of

recent herbal regulations (RDC 48) which recommend the preparation of medicine with the species

because several studies confirms their efficacy and

safety (Brasil 2004a). Only four native species

are recommended by RDC 48: Maytenus ilicifolia

(Schrad.) Planch, M. glomerata Sprengel, Passiflora species, and P. cupana Kunth (Brasil 2004b).

The influence of RDC 48 on the production of

medicine with these plants can be clearly observed

in Table 2, which shows that several companies

currently use these plants to prepare medicine.

Thirty-eight species used in 1995/1996 were described in the first edition of FBRAS, published

in 1929, showing their importance also in conventional medicine of the past (Brando et al. 2006,

2008a). However, only nine have monographs in

the fourth edition of FBRAS, published in 2004:

B. trimera (Less.) DC, M. glomerata Sprengel,

M. ilicifolia (Schrad.) Planch, Phyllanthus niruri

L., Phyllanthus tenellus Roxb,E. mulungu Martius ex Benth, S. adstringens (Mart.) Coville, P.

ipecacuanha (Brot.) Stokes, P. acuminata Benth,

Pilocarpus jaborandi Holmes, Pilocarpus microphyllus Stapf ex Wardl., and P. cupana Kunth.

The inclusion of a monograph for a species in the

recent editions of FBRAS stimulates its use in

the production of medicine, as shown in Table 2.

This situation points out the urgent necessity

of ecological and conservation studies for these

species since the bulk of plants traded in Brazil

is harvested from wild populations which results

in numerous local extinctions. Only P. cupana

376

Kunth is cultivated in the north of the country and the Psychotria and Pilocarpus species

are already considered threatened by extinction

(IBAMA 2005/2006; Silva et al. 2001).

There is a preoccupying risk that this expansion

of the herbal market poses a threat to biodiversity through overharvesting of the raw materials (Botha et al. 2004; Huang et al. 2002; WHO

2007; Taylor 2008). In this study, a beneficial

correlation from a conservation perspective was

found between the collection of wild medicinal

plants and plant organs used in the preparation

of the pharmaceutical products since 1995/1996.

The herbal regulations demand that the companies acquire raw material of certified origin

in order to reduce the genetic erosion of many

species. This fact is also important in light of the

fact that, besides Pilocarpus and Psychotria, the

species Lychnophora, Anemopaegma, and Hymenaea are considered threatened by extinction

today (IBAMA 2005/2006; Silva et al. 2001). Today, only two suppliers furnish native species for

the companies in Minas Gerais. The origin of the

plants is not reported by these suppliers raising

the need to evaluate the source of the material.

The reduction in plant use by the companies may

lead to a decrease in the collection pressure on

the plant species. It also reveals how the Brazilian

herbal regulation may have reduced the impact

on the collection of the native medicinal plants,

especially the barks and roots, contributing to the

reduction of the genetic erosion of these species;

although no scientific study was done on this aspect. This does not take into account the collection of plant material that is sold in free markets

throughout the country, as these remain free from

regulation.

Despite being considered a local-level study,

our results provide important data that can complement national and international studies. It

points out how the regulation of herbal medicines

has changed the use of medicinal plants by companies in Brazil. Only species meeting requirements

of efficacy and security proven by pharmacological studies can be used for making pharmaceutical

products and registered as medicine. As a consequence, such rules have contributed to a reduction

in the collection of native plants and can represent

a real strategy for the conservation of wild species.

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

The study also points to an urgent need for pharmacological and toxicological studies of the native

medicinal species, as well as studies on the ecology

and their conservation.

Acknowledgements The authors thank Professor Sir

Ghillean Prance for a critical reading of this manuscript;

CMT Souza and RL Vieira for the excellent technical assistance; Companies Catedral, Belm Jardim, Rodomonte,

Globo, Copo Medicinal, and Magaraz for information

and plant materials; FAPEMIG (PPM/ 2007) for research

grants; and CNPq for fellowships (Pq, IC).

References

Albuquerque, U. P., Monteiro, J. M., Ramos, M. A., &

Amorim, E. L. C. (2007). Medicinal and magic plants

from a public market in northeastern Brazil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 110, 7691. doi:10.1016/

j.jep.2005/2006.09.010.

Amorozo, M. C. M. (2002). Uso e diversidade de plantas medicinais em Santo Antnio do Levenger,

MT, Brasil. Acta Botnica Braslica, 16(2), 189203.

doi:10.1590/S0102-33062002000200006.

Begossi, A., Hanazaki, N., & Yamashiro, J. Y. (2002).

Medicinal plants in the Atlantic Forest (Brazil):

knowledge, use and conservation. Kuman Ecology,

30(3), 281299. doi:10.1023/A:1016564217719.

Botha, J., Witkowski, E. T. F., & Shackleton, C. M. (2004).

Market profiles and trade in medicinal plants in the

Lowveld, South Africa. Environmental Conservation,

31, 3846. doi:10.1017/S0376892904001067.

Brando, M. G. L. (1996). A participao do Laboratrio

de Farmacognosia da UFMG no aprimoramento do

produto fitoterpico comercializado em Minas Gerais.

Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 5(2), 201210.

Brando, M. G. L., Cosenza, G. P., Moreira, R. A.,

& Monte-Mor, R. L. M. (2006). Medicinal plants

and other botanical products from the Brazilian Official Pharmacopoeia. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 16, 408420. doi:10.1590/S0102-695X2005/

2006000300020.

Brando, M. G. L., Diniz, B. G., & Monte-Mr, R. L. M.

(2004). Plantas medicinais: um saber ameaado. Cincia Hoje, 35, 6466.

Brando, M. G. L., Zanetti, N. N. S., Oliveira, G. R. R.,

Goulart, L. O., & Monte-Mr, R. L. (2008a). Other

medicinal plants and botanical products from the first

edition of the Brazilian Official Pharmacopoeia. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 18(1), 127136.

Brando, M. G. L., Zanetti, N. N. S., Oliveira, P.,

Grael, C. F. F., Santos, A. C. P., Monte-Mr, R.

L. (2008b). Brazilian plants described by European

naturalists in 19th century and in Pharmacopoeia.

Environ Monit Assess (2010) 164:369377

Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 120, 141148. doi:

10.1016/j.jep.2008.08.004.

Brasil, Ministrio da Sade (1995). Agncia Nacional de

Vigilncia sanitria (ANVISA). Portaria 06 de 31 de

janeiro de 1995. Braslia: Dirio Oficial da Unio.

Brasil (2004a). Resoluo n 89, de 16 de maro de

2004 da Agncia Nacional de Vigilncia Sanitria.

http://e-legis.anvisa.gov.br. Accessed Sept. 2007.

Brasil (2004b). Resoluo RDC n 48, de 16 de maro

de 2004 da Agncia Nacional de Vigilncia Sanitria.

http://e-legis.anvisa.gov.br. Accessed Sept. 2007.

Calixto, J. B. (2000). Efficacy, safety, quality control, marketing and regulatory guidelines for herbal medicines (phytotherapeutic agents). Brazilian Journal

of Medical and Biological Research, 33, 179189.

doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2000000200004.

Calixto, J. B. (2005). Twenty-five years of research on

medicinal plants in Latin America. A personal view.

Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 100(12), 131134.

doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.004.

Carvalho, A. C. B., Balbino, E. E., Maciel, A., & Perfeito,

J. P. S. (2008). Situao do registro de medicamentos

fitoterpicos no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 18(2), 314319.

Casamada, R. S. M. (1977). Tratado de Farmacognosia.

Barcelona: Editorial Cientifico Medica.

Dean, W. (1996). With broadax and firebrand: The destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic forest (p. 482). Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Deutschmann, F., Hofmann, B., Sprecher, E., Stahl,

E. (1984). Pharmazeutische Biologie. Drogenanalyse

I: Morphologie und Anatomie (2nd ed.). Stuttgart:

Gustav Fischer.

Di Stasi, L. C., & Hiruma-Lima, C. A. (2002). Plantas

Medicinais na Amaznia e na Mata Atlntica. So

Paulo: Editora UNESP.

Eschricher, W. (1988). Pulver Atlas der Drogen des

Deutschen Arzneibuches (335 p.). Stuttgart: Gustav

Fischer.

Fernandes, T. M. (2004). Plantas Medicinais. Memria da

Cincia no Brasil (260 p.). Rio de Janeiro: Editora

Fiocruz.

Ferreira, S. H. (org.) (1998). Medicamentos a partir de

plantas medicinais no Brasil (132 p.). Rio de Janeiro:

Academia Brasileira de Cincias.

Gilg, E., Brendt, W., & Schrhoff, P. M. (1942). Farmacognosia. Barcelona: Editorial Labor.

Giulietti, A. M., Harley, R. M., Queiroz, L. P., Wanderley,

M. G. L., & Berg, C. V. D. (2005). Biodiversidade e

conservao das plantas no Brasil. Megadiversidade, 1,

5261.

Golse, J. (1955). Prcis de Matire Mdicale. Paris: G. Doin

& Co.

Huang, H., Han, X., Kang, L., Raven, P., Jackson, P.

W., & Chen, Y. (2002). Conserving native plants in

China. Science, 297, 935936. doi:10.1126/science.297.

5583.935b.

377

IBAMAInstituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos

Recursos Naturais Renovveis (2005/2006). http://

www.ibama.gov.br/flora/divs/plantasextincao.pdf. Accessed Sept. 2008.

Langhammer, L. (1989). Bildatlas zur mikroscopischen

Analytik pflanzlicher Arzneidrogen (241 p.). Berlin:

Walter de Gruyter.

Melo, J. G., Amorim, E. L. C., & Albuquerque, U.

P. (2008). Native medicinal plants commercialized

in Brazil priorities for conservation. Environmental

Monitoring and Assessment. doi:10.1007/s10661-0080506-0.

Michalski, F., Peres, C. A., & Lake, I. R. (2008).

Deforestation dynamics in a fragmented region of

southern Amazonia: Evaluation and future scenarios.

Environmental Conservation, 35(2), 93103. doi:10.

1017/S0376892908004864.

Oliveira, F., Akisue, G., & Akisue, M. K. (1991). Farmacognosia. Livraria (412 pp.), So Paulo: Atheneu

Editora.

Rates, S. M. K. (2001). Plants as source of drugs. Toxicon,

39(5), 603613. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(00)00154-9.

Shanley, P., & Luz, L. (2003). The impacts of forest

degradation on medicinal plant use and implications

for health care in eastern Amazonia. BioSciense,

53, 573584. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0573:

TIOFDO]2.0.CO;2.

Shanley, P., & Rosa, N. A. (2005) Conhecimento em

eroso: um inventrio etnobotnico na fronteira de

explorao da Amaznia oriental. Boletim do Museu

Paraense Emlio Goeldi 1(1), 147171.

Silva, S. R., Buitrn, X., Oliveira, L. H., & Martins, M. V.

(2001). Plantas medicinais do Brasil: Aspectos sobre

legislao e comrcio. Quito: TRAFFIC Amrica do

SulIBAMA.

Taylor, D. A. (2008). New yardstick for medicinal plant

harvests. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(1),

2128.

Wagner, H., & Bladt, S. (1996). Plant drug analysis. A thin

layer chromatography atlas (384 p.). Berlin: Springer.

Wolters, B. (1992). Jarhtausend vor Kolumbus: Indianische kulturpflanzen und Arzneidrogen. Deutsche

Apotheker-Zeitung, 40, 110.

World Health Organization (1993). Research guidelines

for evaluating the safety and efficacy of herbal medicines (86 p.). Manila: WHO Regional Office for the

Western Pacific.

World Health Organization (1998). Quality control methods for medicinal plants materials (114 p.). Geneva:

WHO.

World Health Organization (2002). Traditional medicine

strategy 20022005. Geneva: WHO.

World Health Organization (2007). WHO guidelines on

good agricultural and collection practices (GACP) for

medicinal plants. Geneva: WHO.

Youngken, H. W. (1943). Text-book of pharmacognosy.

Philadelphia: Blakiston.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Physical and Chemical Profile and Food Safety of Gluten Free Bread 7229 PDFDokument7 SeitenPhysical and Chemical Profile and Food Safety of Gluten Free Bread 7229 PDFKhaled KayyaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Power Design: Exxtraaa Smoothh.Dokument2 SeitenPower Design: Exxtraaa Smoothh.John GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combined CyclesDokument17 SeitenCombined CyclesMuhammad HarisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Astm A333Dokument7 SeitenAstm A333Luis Evangelista Moura Pacheco100% (3)

- 26529Dokument61 Seiten26529MASTER_SANDMANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Polymers: Recycling and Reprocessing of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Materials Towards Nonwoven ProcessingDokument13 SeitenPolymers: Recycling and Reprocessing of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Materials Towards Nonwoven Processingabilio_j_vieiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMO Performance Standard For Protective Coating and IACS Common Structural RulesDokument76 SeitenIMO Performance Standard For Protective Coating and IACS Common Structural Rulesheobukon100% (2)

- Casting DefectsDokument4 SeitenCasting DefectsHamza KayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hair PresentationDokument7 SeitenHair PresentationxMiracleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class 12 Chemistry Revision Notes The Solid StateDokument21 SeitenClass 12 Chemistry Revision Notes The Solid StateAfreen AnzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical AnalysisDokument16 SeitenJournal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical AnalysisFania dora AslamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rivet Edge Distance Guide - Key Factors for Aircraft DesignDokument2 SeitenRivet Edge Distance Guide - Key Factors for Aircraft Designnirlep_parikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacognosy II by Zahid Olive OilDokument5 SeitenPharmacognosy II by Zahid Olive OilZahid SaleemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tugas Parafrase Jurnal MIPKI RevisiDokument2 SeitenTugas Parafrase Jurnal MIPKI RevisiAl-aminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teach Yourself Electricity and Electronics 3rd Edition ReviewDokument4 SeitenTeach Yourself Electricity and Electronics 3rd Edition ReviewPatricia KalzadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iso 1920 12 2015Dokument11 SeitenIso 1920 12 2015DEBORAH GRASIELLY CIPRIANO DA SILVANoch keine Bewertungen

- Temperature MeasurementDokument25 SeitenTemperature MeasurementPratik GhongadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECJ Dossier 2020 SustainabilityDokument49 SeitenECJ Dossier 2020 SustainabilityJose LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmaceutical Development: Training Workshop OnDokument52 SeitenPharmaceutical Development: Training Workshop OnYULI NURFAIDAHNoch keine Bewertungen

- CML101 Tutorial 2 AnswersDokument4 SeitenCML101 Tutorial 2 AnswersDeveshNoch keine Bewertungen

- 23 07 00 HVAC InsulationDokument17 Seiten23 07 00 HVAC InsulationAhmed AzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemical Stock UpdatedDokument21 SeitenChemical Stock UpdatedPraise and worshipNoch keine Bewertungen

- CannabisDokument18 SeitenCannabistechzones67% (3)

- Sanitary FittingsDokument58 SeitenSanitary FittingsMherlieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dearman Handbook 2015 PDFDokument164 SeitenDearman Handbook 2015 PDFCURRITOJIMENEZ100% (1)

- Material Safety Data Sheet: Product: G Paint Lacquer PaintsDokument4 SeitenMaterial Safety Data Sheet: Product: G Paint Lacquer PaintsYap HSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friedrich MohsDokument7 SeitenFriedrich MohsJohnMadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acids and bases pKa tableDokument6 SeitenAcids and bases pKa tablejuan pablo isaza riosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02-Samss-005 2014Dokument16 Seiten02-Samss-005 2014My SinuNoch keine Bewertungen

- PSM Role in Safety, Advantages & DisadvantagesDokument22 SeitenPSM Role in Safety, Advantages & DisadvantagesSIMON'S TVNoch keine Bewertungen