Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management: A B S T R A C T

Hochgeladen von

safwand90Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management: A B S T R A C T

Hochgeladen von

safwand90Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

C

L I N I C A L

R A C T I C E

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Syndrome: Diagnosis

and Management

Reginald H.B. Goodday, DDS, MSc,

FRCD(C)

David S. Precious, DDS, MSc,

FRCD(C )

Archibald D. Morrison, DDS, MSc,

FRCD(C)

Chad G. Robertson,

DDS

A b s t r a c t

Increased awareness that changes in sleeping habits and daytime behaviour may be attributable to obstructive

sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) has led many patients to seek both information and definitive treatment. The purpose

of this article is to provide information to dentists that will enable them to identify patients who may have OSAS

and to assist these patients in making informed decisions regarding treatment options. In patients who have

identifiable anatomic abnormalities of the maxilla and mandible resulting in a narrow pharyngeal airway,

orthognathic surgery appears to be an excellent treatment option.

MeSH Key Words: sleep apnea, obstructive/diagnosis; sleep apnea, obstructive/surgery

Preval

ence

n increasing number of people are

realizing that changes in their sleeping

habits and daytime behav- iour may be

attributable to obstructive sleep apnea

syndrome (OSAS). This new awareness has

led many patients to seek both information

and definitive treatment. Because the jaws

and related structures influence the development of this syndrome, dentists play an

important role in both identifying patients

who should be assessed by sleep specialists

and instituting treatment in selected cases.

The purpose of this article is to provide

information to dentists that will enable them

to identify patients who may have OSAS and

to assist these patients in making informed

decisions regarding treatment options.

OSAS is characterized by repetitive

episodes of upper airway obstruction that

occur during sleep usually in asso- ciation

with a reduction in blood oxygen

saturation.1 The prevalence of OSAS in the

middle-aged population (30 to

60 years) is 4% in men and 2% in women. 2

However, prevalence rises dramatically

with age, to an estimated

28% to 67% for elderly men and 20% to

54% for elderly women.3

J Can Dent Assoc 2001; 67(11):652-8

This article has been peer reviewed.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of OSAS are

related to obstruction of the upper airway,

fragmented sleep, and the respiratory and

cardiovascular consequences of disordered

breathing. Excessive daytime somnolence is a

key feature of OSAS resulting from disrupted

sleep. Patients may report that they frequently

fall asleep during the day while driving,

working, reading and watching television.4

Thus, perform- ing activities related to

transportation or the use of machin- ery and

heavy equipment can put both the patient and

December 2001, Vol. 67, No. 11

others at significant risk of injury.5,6 Chronic

daytime sleepiness also leads to poor work

performance and decreased productivity.

Snoring, ranging in severity from mild to

extremely loud, is invariably present. The

partners of people with OSAS may witness

gasping, choking or periods of apnea, with

repeated arousals through the night. In many

cases these symptoms are significant enough

that the partner sleeps in another room.

When questioned in the morning the patient

is usually unaware of the frequency of

arousals. Other complaints include a feeling

of not being rested despite a full night of

sleep, dry mouth, morning headaches,

absence of dreams, fatigue, decreased libido

and symptoms of depression.

Journal of the Canadian Dental Association

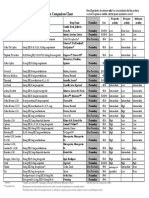

Figure 1a: Lateral cephalometric radiograph of a patient with

obstruc- tive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) indicates the narrow

anteroposte- rior dimension of the pharyngeal airway at the level of

the soft palate and the base of tongue (arrows).

The respiratory consequences of OSAS are

related to the extent of hypoxemia and

hypercapnia that develop as a result of the

disordered breathing. Advanced cases of

OSAS are associated with pulmonary

hypertension, corpulmonale, chronic carbon

dioxide retention and poly- cythemia.7 The

cardiovascular consequences of OSAS may

include systemic hypertension, cardiac

arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, and

cerebral vascular accidents, all of which lead

to a higher mortality rate than in the general

population.8,9

Clearly, OSAS can be a debilitating and

potentially life- threatening condition. Thus,

both proper diagnosis and appropriate

treatment are important.

Diagnostic Tools

The dental office can play an important

role in screen- ing patients who may have

OSAS by including 2 questions on the

medical questionnaire: Do you snore

loudly? Do you have difficulty staying awake

when you are inactive (e.g., while reading,

watching television or driving)? A posi- tive

response to these 2 questions should lead

the dentist to suspect OSAS. Additional

questions should then be asked to help

identify the extent of the problem: Has your

part- ner witnessed pauses in your breathing

Figure 1b: Postoperative lateral cephalometric radiograph of the

same patient after maxillomandibular advancement. Note the significant increase in the pharyngeal airway space at the level of the soft

palate and the base of tongue.

while you are asleep? Have you fallen asleep in

a potentially dangerous situation? Has your

work

performance

suffered?

Has

your

concentra- tion, memory or mood been

affected?

If the history supports the diagnosis of OSAS,

the patient should be referred to a sleep

disorders laboratory for

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Diagnosis and

overnight polysomnography, the objective

method of estab- lishing the diagnosis and

assessing

the

potential

success

of

treatment. The most important variables

used in determin- ing the presence and

severity of OSAS are the apnea index, the

hypopnea

index,

the

respiratory

disturbance index (RDI) and the lowest

oxyhemoglobin saturation.10 Apnea is

defined as cessation in air flow for 10

seconds or more, and the apnea index is

the number of apneic episodes occurring in

a 1-hour period.11 Hypopnea has been

defined as a 50% reduction in tidal volume

for more than 10 seconds, and the

hypopnea index is the number of

hypopneic episodes in a 1-hour period.11

The RDI is defined as the number of

apneic and hypopneic episodes per hour of

sleep.11

The

lowest

oxyhemoglobin

Management

saturation

is simply the lowest oxygen

saturation measured by pulse oximetry

during the study. OSAS is diagnosed if the

RDI reaches a certain threshold level,

typically 5 or 10.3,11 OSAS becomes clinically significant when the RDI is greater than

20 and oxygen desaturation events fall to

a level below 80% to 85%.12

Caus

es

Obstructive sleep apnea can be caused by

an anatomic abnormality that narrows or

obstructs the airway. Investigations to

localize the site of functional obstruction in

the upper airway have shown that there is

rarely a single site of occlusion. Obstruction

more commonly occurs at multiple levels of

the upper airway during episodes of

hypopnea and apnea13 (Figs. 1a, 1b).

Figure 2: Preoperative photograph of the patient depicted in Figure

1. Patients without a clinically obvious facial deformity may

benefit from maxillomandibular advancement. As this photograph

indicates, patients with OSAS may not be obese.

In any patient, upper airway patency is

maintained

through

many

interrelated

anatomic and physiologic factors.14 Normally,

negative intrapharyngeal pressure devel- ops

during inspiration. Collapse of the airway is

prevented by the action of the pharyngeal

abductor and dilator muscles. The pharynx

consists of 3 segments: the naso- pharynx,

the oropharynx and the hypopharynx. The

muscles become hypotonic during sleep, and

airway stability becomes dependent

on

pharyngeal size and pharyngeal tissue

compliance in these 3 segments.14,15 If the

compliance of the soft tissues in the narrowed

segments of the passive airway is inadequate

to offset the negative intraluminal pres- sure

created during inspiration, airway obstruction

occurs. As a result, the central nervous

system adjusts to a lighter level of sleep by

increasing muscle tone to allow opening of

the airway and resumption of the breathing

cycle.

Once the diagnosis of OSAS has been

confirmed but before treatment is instituted,

upper airway imaging is often performed to

obtain additional information regarding the

anatomy of the airway. For example, clinical

examination does not always reveal a gross

facial deformity (Fig. 2), but cephalometric

radiography can help in determining the

Figure 3: Lateral cephalometric radiograph of a patient with OSAS

who underwent uvulopalatopharyngoplasty demonstrates a thick,

bulbous soft palate (arrow) associated with a narrow

nasopharyngeal airway.

anatomic factors contributing to OSAS.

This information can then be used to direct

treatment, particularly surgery, and may

lead to more predictable treatment

outcomes. Studies involving cephalometric

radiography in patients with OSAS have

demonstrated that these patients have

smaller

retropositioned

mandibles,

narrower posterior airway spaces, and

larger tongues and soft palates than

control patients, as well as inferiorly positioned

hyoid bones and retropositioned maxillae.16

Management

OSAS can be managed nonsurgically or

surgically. The treatment should target the

potential contributing factors identified by the

history, the physical examination and upper

airway imaging. The severity of the patients

condition must also be considered in developing

a treatment plan.

Nonsurgical Management

Because obesity is a risk factor for OSAS, a

reduction in body weight can reduce sleep

apnea.17,18 However, the patient may have

difficulty losing weight, particularly in more

severe cases, because excessive daytime

somnolence and fatigue may discourage the

patient from exercising. The severity of the

OSAS may have to be reduced through some

other form of treatment before an exercise

program can be started. It is important to

note, however, that many patients with OSAS

are not obese (Fig. 2).

The most successful nonsurgical treatment

is continuous positive airway pressure

(CPAP). The use of CPAP in the treatment of

OSAS was first described in 1981.19 Since

then it has become the gold standard in the

treatment of this condition.10

However,

because of physical discomfort asso- ciated

with wearing the unit, drying of the nasal and

oral mucosal membranes, dislodgement

during

sleep,

noise

and

the

social

consequences of using the unit, compliance

may be as low as 46%.20

Oral appliances can also be used in the

treatment of OSAS.21 A review of 20 studies,

involving a total of 304 patients, revealed

that oral appliances were effective in 51% of

cases, as defined by achievement of an RDI

of less than

10.22

In 2 studies that compared oral

appliances for mandibular advancement with

CPAP, the oral appliances were effective in

mild to moderate cases but were less effective than nasal CPAP in more severe

cases.23,24 In both these studies the patients

strongly preferred the oral appliance over

nasal CPAP for reasons of comfort. The most

signifi- cant negative long-term effects of oral

appliances are temporomandibular joint

problems and movement of teeth.25-27 Tooth

movements may result in a posterior open

bite and decreased anterior overjet.21

Other nonsurgical treatments for OSAS

include medica- tions such as protriptyline

and medroxyprogesterone. Protriptyline, a

tricyclic antidepressant, has shown reasonable symptomatic improvement of OSAS and

may

reduce

the

degree

of

oxygen

desaturation, but anticholinergic side effects

and incomplete efficacy limit its use.7

Medroxy- progesterone has limited value in

the treatment of OSAS but it may be effective

in cases of obesity hypoventilation syndrome

with chronic hypercapnia.7

Surgical

Management

Tracheostomy was the first successful

surgical treatment for

OSAS.

It

was

introduced for this purpose in the

1970s.28 This procedure, which bypasses the

upper airway, is successful in virtually 100%

of cases.29 Complications associated with

tracheostomy include hemorrhage, recurrent infections, airway granulations, and

tracheal or stomal stenosis.29 The medical

and obvious social problems asso- ciated

with tracheostomy have stimulated the

search for alternatives.7

Fujita and others30 first described the use

of the uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) for

the treatment of OSAS in 1981. This

procedure involves shortening the soft

palate, amputating the uvula, and removing

redundant lateral and posterior pharyngeal

wall mucosa from the oral pharynx. Despite

the popularity of this procedure, reviews

have reported improvement in less than 50%

of patients and complete control of OSAS

in 25% or less.31,32

Postoperative

lateral

cephalometric

radiographs of patients who have undergone

UPPP and whose symptoms persist reveal that

the soft palate has been shortened but is much

thicker,

which

results

in

a

narrow

nasopharyngeal

airway

(Fig.

3).

The

unsatisfactory results obtained with UPPP have

contributed to the realization that there are

usually multiple sites of obstruction in the

upper airway. When patients are selected on

the

basis

of

retropalatal

obstruction

demonstrated by computed tomography during

wakeful- ness or by catheter measurements of

nasal pharyngeal pressure, the success rate of

UPPP is only 50%.16

UPPP also carries a risk of significant

hemorrhage,

and

patients

report

substantial postoperative pain, which may

last

for

an

extended

period.

Velopharyngeal

insufficiency

and

nasophyaryngeal

stenosis

may

also

complicate UPPP.10

Use of orthognathic surgery to treat

OSAS began toward the end of the 1970s,

when

mandibular

advancement

was

reported to have reversed the symptoms

of OSAS.33,34 Since then, this procedure

has become widely accepted.11,35-42

Orthognathic treatment for OSAS may

involve advance- ment of the maxilla,

mandible or chin (Fig. 4). These 3

procedures can be performed in any

combination, but advancement of the

maxilla and the mandible, with or without

advancement genioplasty, is the most

common procedure. The treatment plan is

based

on

craniofacial

cephalometric

analysis, which determines whether the

position of the maxilla, mandible and chin

are normal or abnormal. The architectural

and structural craniofacial analysis of

Delaire43 allows precise planning of the

surgical advancement to maximize the

increase in pharyngeal dimensions while

maintaining normal facial balance.

Hochban and others35 reported a series

of 38 consecu- tive patients with OSAS

treated by 10 mm maxillo- mandibular

advancement. Patients were selected on

the basis of the results of lateral

cephalometric radiography; those who had

pharyngeal narrowing, with or without

retrognathic mandibles, were offered the

procedure.

Polysomnographic

sleep

studies were performed preopera- tively

and 2 months after surgery. In 37 of the 38

patients, postoperative RDI was reduced to

below 10.

Waite

and

others44

performed

maxillomandibular

advancement in 23

patients with obstructive sleep apnea. All of

the patients had preoperative RDI of greater

than 20 and some form of craniofacial

deformity. Adjunctive procedures such as

partial turbinectomy, septal reconstruction

and advancement genioplasty were also

performed, depending on individual variation.

Sleep studies were performed and lateral

cephalometric measurements obtained 1 and

6 weeks after surgery. Surgical success,

defined as RDI of less than

10, was 65%, although 96% of the patients

showed both subjective and objective

improvement.

Goodday

and

others45

compared

preoperative

and

postoperative

cephalometric radiographs in 25 consecutive

patients who had undergone orthognathic

surgery for the treatment of OSAS. The

median increase in the distance between the

posterior pharyngeal wall and the soft palate

was

100%. Similarly, the median increase in the

distance between the posterior pharyngeal

wall and the base of tongue was

81%. These findings help explain why

selected patients experience improvement

after orthognathic surgery.

Robertson

and

others46

studied

subjective

outcomes

after

maxillomandibular advancement for the

treatment of OSAS. Twenty-four patients

completed a questionnaire a mean of 24

months after surgery. They reported an

Figure 4a: Preoperative photograph of a patient with OSAS.

Figure 4b: Postoperative photograph of the same patient 6 months

after maxillomandibular advancement.

Figure 4c: Preoperative lateral cephalometric radiograph of the

same patient shows the narrow pharyngeal airway space.

Figure 4d: Lateral cephalometric radiograph of the same patient

after

maxillomandibular

advancement

shows

significant

improvement in the pharyngeal airway space.

improvement in daytime sleepiness from the

levels seen in patients with severe OSAS to

levels similar to those seen in normal

controls. Statistically significant reductions

were observed in the number of patients

reporting

problems

with

memory,

concentration and stress. Of patients who

snored preoperatively, 45% stopped snoring

and 45% reported a reduction in snoring

severity.

Compliance is not a factor in the success

of orthognathic

surgery as it is for CPAP and oral appliances.

Relative

to

tracheostomy

and

CPAP,

orthognathic surgery is more socially accepted.

It is also more successful in treating severe

OSAS than UPPP and oral appliances. Recent

studies

have

demonstrated

significant

improvements in OSAS symp- toms in

patients who have undergone orthognathic

surgery, and this procedure is associated with

a high level of patient satisfaction and low

risk.47

Conclusions

OSAS is a common condition associated

with significant

morbidity and mortality. It is therefore

important that

dental professionals be aware of the signs

and symptoms of

OSAS, so that the diagnosis can be

confirmed and treatment initiated as soon as possible. As

knowledge about the

pathophysiology of OSAS improves,

treatments may be

designed to address the specific causes of

the condition. In

patients with identifiable anatomic

abnormalities of the

maxilla and mandible resulting in a narrow

pharyngeal

airway, orthognathic surgery appears to be

an excellent

treatment option. C

Dr. Goodday is associate professor and head, division of oral and

maxillofacial surgery, Dalhousie University.

Dr. Precious is professor and chair, department of oral and

maxillofa- cial sciences, Dalhousie University; head, department of

maxillofacial surgery, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre

(Victoria General Hospital) and director of the 6-year MD/MSc

graduate oral and maxillofacial surgery programme, Dalhousie

University.

Dr. Morrison is an assistant professor of oral and maxillofacial

surgery, Dalhousie University.

Dr. Robertson is a resident in oral and maxillofacial surgery,

Dalhousie University.

Correspondence to: Dr. Reginald H.B. Goodday, Division of

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS

B3H 3J5. E-mail: reginald.goodday@dal.ca.

The authors have no declared financial interest.

References

1. Diagnostic Classifications Steering Committee:

The international

classification system of sleep disorders diagnostic and

coding manual.

Rochester, MN: American Sleep Disorders Association,

1990.

2. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S,

Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing in middle-aged

adults. N Engl J Med

1993; 328(17):1230-5.

3. Goodday RH. Nasal respiration, nasal airway

resistance, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin

North Am 1997;

9(2):167-77.

4. Bahammam A, Kryger M. Decision making in

obstructive sleep-

disordered breathing: putting it all together. Otolaryngol

Clin North Am

1999; 32(2):333-48.

5. Findley LJ, Fabrizio MM, Knight H, Norcross BB, LaForte

AJ, Surratt

PM. Driving simulated performance in patients with sleep

apnea. Am Rev

Respir Dis 1989; 140(2):529-30.

6. George CF, Boudreau AC, Smiley A. Simulated driving

performance

in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med 1996;

154(1):175-81.

7. Wiggins RV, Schmidt-Nowara WW. Treatment of the

obstructive sleep

apnea syndrome. West J Med 1987; 147(5):561-8.

8. He J, Kryger MH, Zorick FJ, Conway W, Roth T. Mortality

and apnea

index in obstructive sleep apnea. Experience in 385 male

patients. Chest

1988; 94(1):9-14.

9. Shepard JW Jr. Hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias,

myocardial infarction, and stroke in relation to obstructive sleep apnea.

Clin Chest Med

1992; 13(3):437-58.

10. Troell RJ, Riley RW, Powell NB, Li K. Surgical

management of the

hypopharyngeal airway in sleep disordered breathing.

Otolaryngol Clin

North Am 1998; 31(6):979-1012.

11. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Maxillary,

mandibular, and

hyoid advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep

apnea: a review of

40 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 48(1):20-6.

12. Riley RW, Powell N, Guilleminault C. Current

surgical concepts for treating obstructive sleep

apnea syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987;

45(2):149-57.

13. Guilleminault C, Hill MW, Simmons FB, Dewent WC.

Obstructive

sleep apnea: electromyographic and fiberoptic studies.

Exp Neurol 1978;

62(1):48-67.

14. Remmers JE, DeGroot WJ, Sauerland EK, Anch AM.

Pathogenesis

of upper airway occlusion during sleep. J Appl Physiol

1978; 44(8):931-8.

15. Lowe AA, Santamaria JD, Fleetham JA, Price C. Facial

morphology

and obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1986;

90(6):484-91.

16. Schwab RJ, Goldbert AN. Upper airway assessment:

radiographic

and other imaging techniques. Otolaryngol Clin

North Am 1998;

31(6):931-68.

17. Loube DI, Loube AA, Mitler MM. Weight loss for

obstructive sleep

apnea: the optimal therapy for obese patients. J Am

Diet Assoc 1994;

94(11):1291-5.

18. Strobel RJ, Rosen RC. Obesity and weight loss in

obstructive sleep

apnea: a critical review. Sleep 1996; 19(2):104-15.

19. Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L.

Reversal of obstructive sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure

applied through

the nares. Lancet 1981; 1(8225):862-5.

20. Sanders MH, Gruendl CA, Rogers RM. Patient

compliance with

nasal CPAP therapy for sleep apnea. Chest 1986;

90(3):330-3.

21. Millman RP, Rosenberg Cl, Kramer NR. Oral

appliances in the treatment of snoring and sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Clin

North Am 1998;

31(6):1039-48.

22. Schmidt-Nowara W, Lowe A, Wiegand L,

Cartwright R, PerezGuerra F, Menn S. Oral appliances for the treatment

of snoring and

obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep 1995;

18(6):501-10.

23. Clark GT, Blumenfeld I, Yoffe N, Peled E, Lavie P. A

crossover study

comparing the efficacy of continuous positive airway

pressure with

anterior mandibular positioning devices on patients

with obstructive

sleep apnea. Chest 1996; 109(6):1477-83.

24. Ferguson KA, Ono T, Lowe AA, Keenan SP, Fleetham

JA. A randomized crossover study of an oral appliance vs nasalcontinuous positive

airway pressure in the treatment of mild-moderate

obstructive sleep

apnea. Chest 1996; 10(5)9:1269-75.

25. Panula K, Keski-Nisula, K. Irreversible alteration in

occlusion caused

by a mandibular advancement appliance: an unexpected

complication of

sleep apnea treatment. Int J Adult Orthodon

Orthognath Surg 2000;

15(3):192-6.

26. Clark GT, Sohn JW, Hong CN. Treating obstructive sleep

apnea and

snoring: assessment of an anterior mandibular positioning

device. J Am

Dent Assoc 2000; 131(6):765-71.

27. Bloch KE, Iseli A, Zhang JN, Xie X, Kaplan V, Stoeckli

PW, and

other. A randomized, controlled crossover trial of two oral

appliances for

sleep apnea treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;

162(1):246-51.

28. Fee WE Jr, Ward PH. Permanent tracheostomy: a

new surgical

technique. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1977; 86(5 Pt 1):635-8.

29. Mickelson SA. Upper airway bypass surgery for

obstructive sleep

apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1998;

31(6):1013-23.

30. Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction

of anatomic

abnormalities of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome:

uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1981; 89(6):923-34.

31. Guilleminault C, Hayes B, Smith L, Simmons FB.

Palatopharyngoplasty and obstructive sleep apnea: a review of 35

cases. Bull Eur

Physiopathol Respir 1983; 19(6):595-9.

32. Conway W, Fujita S, Zorick F, Sicklesteel J, Roehrs T,

Wittig R, and

other. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: one year follow-up.

Chest 1985;

88(3):385-7.

33. Bear SE, Priest JH. Sleep apnea syndrome: correction

with surgical

advancement of the mandible. J Oral Surg 1980; 38(7):5439.

34. Kuo PC, West RA, Bloomquist DS, McNeil RW. The

effect of

mandibular osteotomy in three patients with hypersomnia

sleep apnea.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1979; 48(5):385-92.

35. Hochban W, Conradt R, Brandenburg U, Heitmann J,

Peter JH.

Surgical maxillofacial treatment of obstructive sleep apnea.

Plast Reconstr

Surg 1997; 99(3):619-26.

36. Riley RW, Powell NB, Builleminault C. Obstructive

sleep apnea

syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated

surgical patients.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993; 108:117-25.

37. Powell NB, Riley RW. Obstructive sleep apnea:

orthognathic surgery

perspectives, past, present, and future. Oral Maxillofac

Surg Clin North

Am 1990; 2(4):843-56.

38. Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Maxillofacial

surgery for

obstructive sleep apnea. In: Partinan M,

Guilleminault C, editors.

obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: clinical research

and treatment.

New York: Raven Press; 1989. p. 153-82.

39. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive

sleep apnea

syndrome: a surgical protocol for dynamic upper

airway reconstruction.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993; 51(7):742-7.

40. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Maxillofacial

surgery and

nasal CPAP. A comparison of treatment for

obstructive sleep apnea

syndrome. Chest 1990; 98(6):1421-5.

41. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C, Nino-Murcia

G. Maxillary,

mandibular, and hyoid advancement: An alternative to

tracheostomy in

obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg 1986;

94(5):584-8.

42. Waite PD, Wooten V, Lachner J, Guyette RF.

Maxillomandibular

advancement surgery in 23 patients with

obstructive sleep apnea

syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989; 47(12):1256-61.

43. Delaire J, Schendel SA, Tulasne JF. An architectural

and structural

craniofacial analysis: a new lateral cephalometric

analysis. Oral Surg Oral

Med Oral Pathol 1981; 52(3):226-38.

44. Waite PD, Wooten V, Lachner J, Guyette RF.

Maxillomandibular

advancement surgery in 23 patients with

obstructive sleep apnea

syndrome. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 1989; 47(12):125661.

45. Goodday RH, Precious DS, Morrison A, Robertson C.

Post-surgical

pharyngeal airway changes following orthognathic

surgery in OSAS

patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999; 57(8)Suppl. 1:80.

46. Robertson CG, Goodday R, Precious D, Morrison A,

Shukla S.

Subjective evaluation of orthognathic surgical

outcomes in OSAS

patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000; 58(8)Suppl. 1:57.

47. Precious DS, Lanigan DT, editors. Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgery

Clinics of North America: Risks and Benefits of

Orthognathic Surgery.

Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997. 9(2):133-278.

C D A R E S

C E N T R E

O U R C E

The Resource Centre has compiled an

Information Package on Sleep Apnea.

CDA members can order the package by

contacting the Resource Centre at tel.:

1-800-267-6354 or (613) 523-1770, ext.

2223; fax: (613) 523-6574; e-mail:

info@cda-adc.ca. There is a charge of $10

(plus tax) for the package.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Fast Facts: Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Associated with Obstructive Sleep ApneaVon EverandFast Facts: Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Associated with Obstructive Sleep ApneaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar: Amy S Jordan, David G Mcsharry, Atul MalhotraDokument12 SeitenSeminar: Amy S Jordan, David G Mcsharry, Atul MalhotraSerkan KüçüktürkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On Obstructive Sleep ApneaDokument6 SeitenResearch Paper On Obstructive Sleep Apneaafeatoxmo100% (1)

- Sleep Apnea Term PaperDokument8 SeitenSleep Apnea Term Paperf1gisofykyt3100% (1)

- Pi Is 1089947215001434Dokument18 SeitenPi Is 1089947215001434Anonymous 0Mnt71Noch keine Bewertungen

- SAHOS y AnestesiaDokument10 SeitenSAHOS y AnestesiaEzequielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern Management of Obstructive Sleep ApneaVon EverandModern Management of Obstructive Sleep ApneaSalam O. SalmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 152 Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Anaesthesia 1Dokument6 Seiten152 Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Anaesthesia 1Echo WahyudiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Κουτσουρελάκης ΩΡΛDokument5 SeitenΚουτσουρελάκης ΩΡΛΚουτσουρελακης ΩΡΛNoch keine Bewertungen

- State of The Art: Epidemiology of Obstructive Sleep ApneaDokument23 SeitenState of The Art: Epidemiology of Obstructive Sleep ApneaMelly NoviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pats 200709-155mgDokument8 SeitenPats 200709-155mgDea MaulidiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea Research PaperDokument7 SeitenObstructive Sleep Apnea Research Paperefe8zf19100% (1)

- Jurnal OSADokument10 SeitenJurnal OSAflorensiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treating Obstructive Sleep Apnea Improves Essential Hypertension and Quality of LifeDokument8 SeitenTreating Obstructive Sleep Apnea Improves Essential Hypertension and Quality of Life'ArifahAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthodontics in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients: A Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment Planning, and InterventionsVon EverandOrthodontics in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients: A Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment Planning, and InterventionsSu-Jung KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) - Pulmonary Disorders - MSD Manual Professional EditionDokument15 SeitenObstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) - Pulmonary Disorders - MSD Manual Professional Editionpeterpavel112Noch keine Bewertungen

- Punjabi, 2008Dokument8 SeitenPunjabi, 2008a3llamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and AnaesthesiaDokument21 SeitenObstructive Sleep Apnoea and AnaesthesiajahangirealamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Dental Perspective: Eview RticleDokument9 SeitenManagement of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Dental Perspective: Eview RticleFourthMolar.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypoxia and Stroke: "2% in Younger Adults, But in Healthy Older PeopleDokument3 SeitenHypoxia and Stroke: "2% in Younger Adults, But in Healthy Older PeopleJerahmeel Sombilon GenillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Article Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Diseases: Sad Realities and Untold Truths Regarding Care of Patients in 2022Dokument10 SeitenReview Article Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Diseases: Sad Realities and Untold Truths Regarding Care of Patients in 2022Hashan AbeyrathneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructive Sleep ApnoeaDokument69 SeitenObstructive Sleep ApnoeaPrasanna Datta100% (1)

- Surgicaloptionsforthe Treatmentofobstructive Sleepapnea: Jon-Erik C. Holty,, Christian GuilleminaultDokument37 SeitenSurgicaloptionsforthe Treatmentofobstructive Sleepapnea: Jon-Erik C. Holty,, Christian GuilleminaultJuan Pablo Mejia BarbosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Management of Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Wisconsin Medical JournalDokument5 SeitenSurgical Management of Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Wisconsin Medical JournaladityakurniantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sleep Apnea White Paper Amended March 2019Dokument53 SeitenSleep Apnea White Paper Amended March 2019emanNoch keine Bewertungen

- OSA and Periop Complications 2012Dokument9 SeitenOSA and Periop Complications 2012cjbae22Noch keine Bewertungen

- OSADokument5 SeitenOSAtherese BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cephalometric Analysis of Nonobese Snorers Either With or Without Obstructive Sleep Apnea SyndromeDokument8 SeitenCephalometric Analysis of Nonobese Snorers Either With or Without Obstructive Sleep Apnea SyndromeDiego SolaqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sleep Apnea Research PaperDokument9 SeitenSleep Apnea Research Paperaflbuagdw100% (3)

- Retrospective Analysis of Real-World Data For The Treatment ofDokument10 SeitenRetrospective Analysis of Real-World Data For The Treatment ofvenancioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prov Prot 20118Dokument17 SeitenProv Prot 20118IlhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conference Proceedings: Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and EconomicsDokument13 SeitenConference Proceedings: Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and EconomicsMihaela-Alexandra PopNoch keine Bewertungen

- O S A A O: Bstructive Leep Pnea ND BesityDokument4 SeitenO S A A O: Bstructive Leep Pnea ND BesityBodi EkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demetriades 2010Dokument6 SeitenDemetriades 2010Sai Rakesh ChavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea With Oral Appliances: Research Open AccessDokument9 SeitenTreatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea With Oral Appliances: Research Open AccessVinay MuppanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nasal Obstruction Considerations in Sleep Apnea: Mahmoud I. Awad,, Ashutosh KackerDokument7 SeitenNasal Obstruction Considerations in Sleep Apnea: Mahmoud I. Awad,, Ashutosh KackerSiska HarapanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Treatment of Snoring & Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: Review ArticleDokument10 SeitenSurgical Treatment of Snoring & Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: Review ArticleSiddharth DhanarajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Treatment of A Pattern I Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome Individual - Clinical Case ReportDokument6 SeitenSurgical Treatment of A Pattern I Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome Individual - Clinical Case ReportMatheus CorreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructive Sleep ApneaDokument8 SeitenObstructive Sleep ApneasinanhadeedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Association Between Breathing Route, Oxygen Desaturation, and Upper Airway MorphologyDokument6 SeitenAssociation Between Breathing Route, Oxygen Desaturation, and Upper Airway MorphologyMark Burhenne DDSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jun Jul Page62Dokument7 SeitenJun Jul Page62Rika FitriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using The Pathophysiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea To Teach Cardiopulmonary IntegrationDokument7 SeitenUsing The Pathophysiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea To Teach Cardiopulmonary IntegrationAdiel OjedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respiratory Medicine CME: Athanasia Pataka, Renata L. RihaDokument7 SeitenRespiratory Medicine CME: Athanasia Pataka, Renata L. RihaalgaesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shiffman Et Al 2021 Minimally Invasive Combined ND Yag and Er Yag Laser Assisted Uvulopalatoplasty For Treatment ofDokument8 SeitenShiffman Et Al 2021 Minimally Invasive Combined ND Yag and Er Yag Laser Assisted Uvulopalatoplasty For Treatment ofMário LúcioNoch keine Bewertungen

- JcsmJC1900562 W22pod AnsweredDokument13 SeitenJcsmJC1900562 W22pod Answeredlion5835Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sleep Apnea PresentationDokument73 SeitenSleep Apnea PresentationChad WhiteheadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maxillomandibular Advancement For Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Kasey K. Li, DDS, MDDokument8 SeitenMaxillomandibular Advancement For Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Kasey K. Li, DDS, MDashajangamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On Sleep ApneaDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper On Sleep Apneafvja66n5100% (1)

- Sleep Disorders in Pediatric Dentistry: Clinical Guide on Diagnosis and ManagementVon EverandSleep Disorders in Pediatric Dentistry: Clinical Guide on Diagnosis and ManagementEdmund LiemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consequences of OSADokument11 SeitenConsequences of OSAhammodihotmailcomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sleep Apnea in Renal Patients: Disease of The MonthDokument6 SeitenSleep Apnea in Renal Patients: Disease of The MonthwibowomustokoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome A Systematic Literature ReviewDokument4 SeitenObstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome A Systematic Literature Reviewc5nah867Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On Sleep ApneaDokument7 SeitenLiterature Review On Sleep Apneafvfj1pqe100% (1)

- DescargaDokument7 SeitenDescargaJoel DiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: Definitions, Epidemiology & Natural HistoryDokument6 SeitenObstructive Sleep Apnoea: Definitions, Epidemiology & Natural HistoryRika FitriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Updates On Definition, Consequences, and Management of Obstructive Sleep ApneaDokument7 SeitenUpdates On Definition, Consequences, and Management of Obstructive Sleep ApneapvillagranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capitol SASODokument12 SeitenCapitol SASOClaudia ToncaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ocular Auscultation: A ReviewDokument5 SeitenOcular Auscultation: A ReviewMihnea GamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches in Obstructive Sleep Apnea SyndromeDokument46 SeitenPathophysiological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches in Obstructive Sleep Apnea SyndromeFrancisco Javier MacíasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Science of Emotion (Harvard Medicine)Dokument28 SeitenThe Science of Emotion (Harvard Medicine)Ralphie_BallNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotionally Focused Therapy For Couples and Childhood Sexual Abuse SurvivorsDokument19 SeitenEmotionally Focused Therapy For Couples and Childhood Sexual Abuse SurvivorsEFTcouplesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3b. Bipolar Affective Disorder 2022Dokument53 Seiten3b. Bipolar Affective Disorder 2022mirabel IvanaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- CA Treatment Phyllodes Web AlgorithmDokument4 SeitenCA Treatment Phyllodes Web AlgorithmMuhammad SubhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enraf-Nonius Endolaser 422 ENDokument3 SeitenEnraf-Nonius Endolaser 422 ENRehabilitasi AwesomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Special Topics in Pediatric NursingDokument60 SeitenSpecial Topics in Pediatric NursingRichard S. RoxasNoch keine Bewertungen

- WFWFDokument4 SeitenWFWFSantosh Kumar SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- ALAXAN Module Part1Dokument30 SeitenALAXAN Module Part1api-19864075Noch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Statement For Master in Public Health - 2Dokument2 SeitenPersonal Statement For Master in Public Health - 2fopoku2k2100% (2)

- Treatment Plan TemplatesDokument2 SeitenTreatment Plan TemplatesShalini Dass100% (3)

- The Doctor Will Sue You NowDokument11 SeitenThe Doctor Will Sue You NowMateja MijačevićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrotherapy: DR Ramaiah Choudhary PhysiotherapistDokument13 SeitenElectrotherapy: DR Ramaiah Choudhary Physiotherapistvenkata ramakrishnaiahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grounding TechniquesDokument2 SeitenGrounding TechniquesEderson Vertuan50% (2)

- CompendiumDokument3 SeitenCompendiumKhuong LamNoch keine Bewertungen

- MORAXELLADokument2 SeitenMORAXELLAMarcelo Jover RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Dental Problems and SolutionsDokument4 SeitenJournal of Dental Problems and SolutionsPeertechz Publications Inc.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Decompensated Heart FailureDokument31 SeitenAcute Decompensated Heart Failure568563Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eating Disorders PaperDokument7 SeitenEating Disorders Paperapi-237474804Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cigna Leave Solutions® Claims Service Center P.O. Box 703509 Dallas, TX 75370Dokument13 SeitenCigna Leave Solutions® Claims Service Center P.O. Box 703509 Dallas, TX 75370Jose N Nelly GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Development of Freudian Metapsychology For Schisophrenia Artaloytia2014Dokument26 SeitenA Development of Freudian Metapsychology For Schisophrenia Artaloytia2014Fredy TolentoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contraceptive Comparison ChartDokument1 SeiteContraceptive Comparison ChartdryasirsaeedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acca Toolkit 2018Dokument212 SeitenAcca Toolkit 2018daltonngangi100% (3)

- Cpi Final Assessment ErmcDokument9 SeitenCpi Final Assessment Ermcapi-528037163Noch keine Bewertungen

- All Other NZ McqsDokument36 SeitenAll Other NZ McqsTran Thai SonNoch keine Bewertungen

- @MedicalBooksStore 2017 Pharmaceutical PDFDokument469 Seiten@MedicalBooksStore 2017 Pharmaceutical PDFeny88% (8)

- Health Services For Older Population in ThailandDokument27 SeitenHealth Services For Older Population in ThailandTino PriyudhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDokument5 SeitenAcute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaernitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BarsDokument2 SeitenBarsrichieerishiNoch keine Bewertungen

- BURNS - Concept MapDokument1 SeiteBURNS - Concept MapMayaPopbozhikova89% (9)

- NCP MyomaDokument6 SeitenNCP MyomaIzza Mae Ferrancol PastranaNoch keine Bewertungen