Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chabacano PDF

Hochgeladen von

Cathryn Dominique TanOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chabacano PDF

Hochgeladen von

Cathryn Dominique TanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chabacano

Pilipino Express Vol. 3 No. 21

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

November 1, 2007

Like many stories about

ordinary Filipinos during the early

colonial era, the history of the

Chabacano language is underresearched. The Spaniards studied

many Philippine languages but

they were not very interested in

the heavily Spanish-influenced

language that emerged during their

occupation of the country. The few

accounts that mentioned Chabacano usually dismissed it as

merely broken or bad Spanish

and that attitude persists to this

day. The word Chabacano itself is

a Spanish word that means vulgar,

common or rude and because of

this, some Chabacano speakers

prefer to spell the word as

Chavacano or they refer to the

language according to where it is

spoken; calling it Zamboangueo,

Caviteo, Ternateo, etc.

Linguists began proper studies

of the various dialects of Chabacano in the last century but the

dearth of historical records has

made studying their origins rather

difficult. This has left the door

open for many wannabe historians

to confuse matters with several

conflicting folk tales.

Chabacano in Cavite

The various dialects of Chabacano were formed out of necessity,

like all languages, though scholars

and laypersons disagree about

exactly when and where it all

began. Most believe that the seeds

of the earliest form of Chabacano

were planted in Cavite when many

ethnic groups from throughout the

Philippines and Christian Malays

from Ternate in the Spice Islands

(now a part of Indonesia) were

brought together in 1574 to help

defend Manila against an expected

attack from the forces of the

Chinese pirate, Limahong. The

various language groups working at

the Cavite naval base needed a way

to communicate with each other and

with the soldiers who were barking

the orders in less-than-genteel

Spanish. It was from this situation

that Chabacano began as a simplified form of Spanish a pidgin

language that later developed into a

mixed, or creole language. The fact

that the first Chabacanos learned

their Spanish from the coarse

language of soldiers is probably

why they were called Chabacanos in

the first place and why speakers of

proper Spanish never regarded

them as equals.

However, some historians

disagree with parts of this story and

say that Chabacano did not emerge

until almost a century later when

Catholic Malays settled in Cavite

after the Spaniards had abandoned

the Spice Islands to the Dutch in

1662. These Malays, known as the

Mardicas (likely from the Malay

word merdeka, meaning free),

settled in the town that now shares the

name of their original homeland,

Ternate. They joined with many other

language groups to defend Manila

from yet another Chinese warlord,

Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong).

Chabacano in Zamboanga

Today, Chabacano speakers are

a small minority in Ternate, Cavite

and Cavite City, and their numbers

are dwindling. Another dialect of

Chabacano that was once spoken

in the Ermita district of Manila is

now extinct. However, in Zam-

boanga City, about half the

population of almost 600,000 still

speak their own dialect of the

language. Zamboangueo can be

heard on television and radio, and

read in newspapers and magazines.

It is also spoken outside the city,

throughout the lower half of the

Zamboanga Peninsula and in

places on the nearby island of

Basilan. There are also dialects of

Chabacano in Cotobato and

Davao, though the Davao dialect

has almost disappeared.

The origin story of Zamboangueo follows the same pattern

as Chabacano in Cavite and it is

just as debatable. Some popular

histories mark the origin of this

Chabacano dialect with an exact

date June 23, 1635 as though the

language was created spontaneously

overnight. That was the date when

the Spaniards established Fort San

Jose at the current location of

Zamboanga City. It also had a

polyglot complement of workers

who received their orders from

Mexican and Spanish soldiers.

However, Spain held Fort San

Jose for only 27 years. In 1662, its

soldiers were called back to Cavite

as part of the general consolidation

of forces that was needed to defend

Manila against Koxinga. The

Spaniards abandoned the fort to

their Muslim rivals until they could

return in 1719 to rebuild it and

rename it Fort Pilar.

Major areas where Chabacano is spoken from chabacano.iespana.es

Paul Morrow In Other Words The Pilipino Express November 1, 2007

During the reconstruction,

masons from Cavite, including

Chabacanos, were brought to

the fort to work with migrant

labourers from Cebu, Iloilo

and some of the local ethnic

groups such as the Samals,

Subanons and possibly, some

escaped Muslim slaves. Just as

in Cavite in the previous century, these various language

groups needed to communicate

with each other and with their

Spanish and Mexican bosses.

Eventually, the most successful

dialect of Chabacano was

developed Zamboangueo.

What is Chabacano?

Chabacano is what linguists

call a creole, which is a language

that is formed when two or more

languages have been mixed together. Chabacano has a predominantly Spanish vocabulary

but its grammatical structures are

based on local languages. For

example, like all other Philippine

languages, it does not follow the

gender rules of Spanish. The

masculine el (for the) is often

used where the feminine la

should be used, though la does

exist in Chabacano. The plural

forms, los and las are usually

2

expressed with the neutral Tagalog particle mga, which is often

pronounced maga or mana. In

the case of Zamboangueo,

plural personal pronouns such as

kame, kita, kamo, sila and other

basic words are taken from

Cebuano rather than Spanish.

The chart below contains translations of the Lords Prayer,

which show just some of the

differences between Spanish

and three major dialects of

Chabacano.

E-mail the author at

pilipinoexpress@shaw.ca or visit

www.mts.net/~pmorrow

The Lords Prayer in Spanish and three major dialects of Chabacano from Wikipedia

Spanish

Zamboangueo

Padre nuestro que ests en el Cielo,

santificado sea tu nombre,

venga a nosotros tu Reino,

hgase tu voluntad

en la Tierra

como en el Cielo.

Tata de amon talli na cielo,

bendito el de Uste nombre.

Manda vene con el de Uste reino;

Hace el de Uste voluntad

aqui na tierra,

igual como alli na cielo.

Danos hoy nuestro pan de cada da,

y perdona nuestras ofensas,

como tambin nosotros perdonamos

a los que nos ofenden,

no nos dejes caer en la tentacin,

y lbranos del mal.

Dale kanamon el pan para cada dia.

Perdona el de amon maga culpa,

como ta perdona kame con aquellos

quien tiene culpa kanamon.

No deja que hay cae kame na tentacion

y libra kanamon na mal.

Caviteo

Ternateo

Niso Tata Qui ta na cielo,

quida santificao Tu nombre.

Manda vini con niso Tu reino;

Sigui el qui quiere Tu

aqui na tierra,

igual como na cielo.

Padri di mijotru ta all na cielo,

Quid alaba Bo nombre

Llev cun mijotru Bo trono;

Vin con mijotru Boh reino;

Sigu cosa qui Bo mand aqu na tiehra

parejo all na cielo.

Dali con niso ahora,

niso comida para todo el dia.

Perdona el mga culpa di niso,

si que laya ta perdona niso con aquel

mga qui tiene culpa con niso.

No dija qui cai niso na tentacion,

pero salva con niso na malo.

Dali con mijotro esti da

el cumida di mijotro para cada da;

Perdon qul mg culpa ya hac mijotro con Bo,

como ta perdon mijotro quel mga culpa ya hac el

mga otro genti cun mijotro;

No dij qui ca mijotru na tintacin,

sin hac libr con mijotro na malo.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Chabacano IdentityDokument33 SeitenChabacano IdentityRoel MarcialNoch keine Bewertungen

- PalenqueDokument2 SeitenPalenqueMariann CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zamboangueño Creole Spanish: John M. Lipski and Salvatore SantoroDokument40 SeitenZamboangueño Creole Spanish: John M. Lipski and Salvatore Santoropark sunghoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Untouched Barangays in the Eyes of a Spanish MissionaryDokument13 SeitenUntouched Barangays in the Eyes of a Spanish MissionaryJERIAH BERNADINE FINULIARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legend of The Ten Bornean DatusDokument3 SeitenLegend of The Ten Bornean DatusJomalen GabonadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pampangans: Their Early History and CultureDokument38 SeitenThe Pampangans: Their Early History and CultureNamie DagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zamboangueño Chavacano: Philippine Spanish Creole or Filipinized Spanish Creole?Dokument20 SeitenZamboangueño Chavacano: Philippine Spanish Creole or Filipinized Spanish Creole?Rab'a SalihNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customs of The TagalogsDokument10 SeitenCustoms of The TagalogsNichole AbonalNoch keine Bewertungen

- ChavacanoDokument47 SeitenChavacanoMarife Burgos MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spanish-Module 1 Revised by Festincristine (Mabalacat City College)Dokument55 SeitenSpanish-Module 1 Revised by Festincristine (Mabalacat City College)Festin CristineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Indigenous Writing Systems Adapt to Modern TimesDokument66 SeitenPhilippine Indigenous Writing Systems Adapt to Modern TimesRed MalcolmNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Filipino People Before The Arrival of The SpaniardsDokument16 SeitenThe Filipino People Before The Arrival of The SpaniardsNicole BarnedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presented-by-Group-4-2Dokument15 SeitenPresented-by-Group-4-2visuals.jeanclaudeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Afro-Caribbean Spanish originsDokument46 SeitenAfro-Caribbean Spanish originsAisha Islanders PérezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Things You Need To Know About KapampangansDokument3 Seiten10 Things You Need To Know About KapampangansKhyle JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language_and_Culture_among_Hispanics_inDokument23 SeitenLanguage_and_Culture_among_Hispanics_inwelkelabordeauNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDF-History-of-Spanish LanguageDokument13 SeitenPDF-History-of-Spanish LanguageMiguel Angel GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2Dokument25 SeitenModule 2Dissa Dorothy AnghagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Philippine Communication Systems and the Arrival of Colonial PowersDokument6 SeitenAncient Philippine Communication Systems and the Arrival of Colonial PowersGermaine AquinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filipino people with Spanish ancestryDokument7 SeitenFilipino people with Spanish ancestryLinas KondratasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Spanish CP 1 LANGUAGE CULTURE, CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE (Lengua, Cultura, Costumbres y Etiqueta)Dokument5 SeitenBasic Spanish CP 1 LANGUAGE CULTURE, CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE (Lengua, Cultura, Costumbres y Etiqueta)Yuuki Chitose (tai-kun)Noch keine Bewertungen

- BS CP 1-2Dokument11 SeitenBS CP 1-2Yuuki Chitose (tai-kun)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Customs of The Tagalog IncDokument14 SeitenCustoms of The Tagalog IncoretnallniwlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Vigorous Original Zamboangueño ChavacanosDokument2 SeitenThe Vigorous Original Zamboangueño ChavacanosAstin EustaquioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customs of the Early TagalogsDokument20 SeitenCustoms of the Early TagalogsJennaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salvador - Wee Zbga de AntesDokument18 SeitenSalvador - Wee Zbga de AntesHas SimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Write A Reflection of Two Parts: 1. in What Specific Way(s) Has The Spanish Influence Persisted in The Caribbean/Trinidad and Tobago?Dokument2 SeitenWrite A Reflection of Two Parts: 1. in What Specific Way(s) Has The Spanish Influence Persisted in The Caribbean/Trinidad and Tobago?Cristiano Raghubar100% (2)

- THE FILIPINO PEOPLE BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPAN Hist Module 2Dokument14 SeitenTHE FILIPINO PEOPLE BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPAN Hist Module 2Lyka BalacdaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 1 Introduction To Spanish LanguageDokument3 SeitenLesson 1 Introduction To Spanish LanguageJhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of BaybayinDokument6 SeitenHistory of BaybayinMark Jeeg C. JaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formal Theme 2Dokument5 SeitenFormal Theme 2rickarecintoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Written-Report-G2Dokument10 SeitenWritten-Report-G2El hombreNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Philippine LiteratureDokument3 SeitenHistory of Philippine LiteratureYanna De ChavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 3Dokument16 SeitenChap 3VICTOR MBEBENoch keine Bewertungen

- BTN LexicoDokument4 SeitenBTN LexicoNguyễn Hoài Thương -Tamara - 3TB-20Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indio To FilipinoDokument3 SeitenIndio To Filipinosir_vic2013Noch keine Bewertungen

- Spanish American Dialect Zones - John LipskyDokument17 SeitenSpanish American Dialect Zones - John Lipskymspanish100% (2)

- A Dictionary of New Mexico and Southern Colorado Spanish: Revised and Expanded EditionVon EverandA Dictionary of New Mexico and Southern Colorado Spanish: Revised and Expanded EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala of Buenaventura (Wolff)Dokument16 SeitenVocabulario de Lengua Tagala of Buenaventura (Wolff)Melchor Azur-BorromeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historic Panay Town's Role in Philippine RevolutionDokument9 SeitenHistoric Panay Town's Role in Philippine RevolutionMicaela Buenvenida PenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spanish: A Window To The Hispanic World: by Paul J. HartmanDokument10 SeitenSpanish: A Window To The Hispanic World: by Paul J. HartmanDavid T. Ernst, Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- References - CAPIZDokument34 SeitenReferences - CAPIZDanica OracionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spanish Is A Romance Language (1270)Dokument2 SeitenSpanish Is A Romance Language (1270)JenniferNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spanish: A Language of Indigenous Peoples of The AmericasDokument12 SeitenSpanish: A Language of Indigenous Peoples of The AmericasKhawaja EshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spanish Colonial Era Shaped Filipino Culture and CuisineDokument8 SeitenSpanish Colonial Era Shaped Filipino Culture and CuisineApril Jane PolicarpioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Spanish LanguageDokument5 SeitenIntroduction To Spanish Languagelimitless1502Noch keine Bewertungen

- C02 Excerpts of An Historical View of The Philippine Islands by ZunigaDokument6 SeitenC02 Excerpts of An Historical View of The Philippine Islands by Zunigadan anna stylesNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR. JOSE RIZAL'S ANNOTATIONS TO THE 1609 HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINESDokument69 SeitenDR. JOSE RIZAL'S ANNOTATIONS TO THE 1609 HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINESRoszelle Olmedo100% (1)

- Pre HispanicDokument13 SeitenPre HispanicDonalyn Jamis100% (1)

- Development of Philippine Literature in EnglishDokument15 SeitenDevelopment of Philippine Literature in EnglishJanine Alexandria Villarante100% (1)

- Philippine Modernity and Popular CultureDokument2 SeitenPhilippine Modernity and Popular CultureFriah Mae EstoresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14 The Structure of Pueblos de Indios in The Philippines During The Spanish Colonial PeriodDokument35 Seiten14 The Structure of Pueblos de Indios in The Philippines During The Spanish Colonial PeriodTricia May CagaoanNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Indio To FilipinoDokument3 SeitenFrom Indio To Filipinosir_vic2013Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2016-2017 Early Period Ancient Filipino ScriptDokument222 Seiten2016-2017 Early Period Ancient Filipino ScriptAngelicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPH Lesson6Dokument24 SeitenRPH Lesson6Anabelle ComedieroNoch keine Bewertungen

- PHLit in Spanish EraDokument8 SeitenPHLit in Spanish EraJulie EsmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philippine LiteratureDokument35 SeitenThe Philippine LiteratureRoanne Lagua100% (1)

- Dictionary: New MexicoDokument212 SeitenDictionary: New MexicoLuis MejiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language PolicyDokument1 SeiteLanguage PolicyJocel ConsolacionNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.3 The Spanish LanguageDokument20 Seiten1.3 The Spanish LanguageIra Rayzel JiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Design and Methods DiscussedDokument1 SeiteResearch Design and Methods DiscussedCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Design and Methods DiscussedDokument1 SeiteResearch Design and Methods DiscussedCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Design and Methods DiscussedDokument1 SeiteResearch Design and Methods DiscussedCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stamps Around The WorldDokument5 SeitenStamps Around The WorldCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutrition Global Health: Micheline Beaudry, Ph.D. Université LavalDokument20 SeitenNutrition Global Health: Micheline Beaudry, Ph.D. Université LavalCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Design and Methods DiscussedDokument1 SeiteResearch Design and Methods DiscussedCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child and Adolescent DevelopmentDokument22 SeitenChild and Adolescent DevelopmentCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

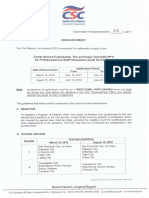

- ExamAnnouncement 04, s2017 - CSE-PPT For CY2018 PDFDokument9 SeitenExamAnnouncement 04, s2017 - CSE-PPT For CY2018 PDFCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Assessment FeesDokument6 SeitenList of Assessment FeesBenjo FransiscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ExamAnnouncement 04, s2017 - CSE-PPT For CY2018 PDFDokument9 SeitenExamAnnouncement 04, s2017 - CSE-PPT For CY2018 PDFCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zamboanga's Riddles, Proverbs, Myth and LegendDokument7 SeitenZamboanga's Riddles, Proverbs, Myth and LegendCrystal Padilla100% (1)

- Zamboanga's Riddles, Proverbs, Myth and LegendDokument7 SeitenZamboanga's Riddles, Proverbs, Myth and LegendCrystal Padilla100% (1)

- PUP COED Field Study at Western Bicutan National High SchoolDokument1 SeitePUP COED Field Study at Western Bicutan National High SchoolCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- LinksDokument1 SeiteLinksCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kasabihan AtbpDokument7 SeitenKasabihan AtbpCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hiragana 01Dokument3 SeitenHiragana 01AdriánFigueroaMondragónNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health and Maintenance - NUDI 1013Dokument35 SeitenHealth and Maintenance - NUDI 1013Cathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cebuano Language Origin and History in the PhilippinesDokument20 SeitenCebuano Language Origin and History in the PhilippinesCathryn Dominique Tan67% (3)

- Waray-Waray - EthnologueDokument2 SeitenWaray-Waray - EthnologueCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSCForm48 DailyTimeRecord (DTR)Dokument1 SeiteCSCForm48 DailyTimeRecord (DTR)H.K. DL80% (5)

- L04 C04 System UnitDokument10 SeitenL04 C04 System UnitLý Quốc PhongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baybayin Variants and Styles GuideDokument16 SeitenBaybayin Variants and Styles GuideCathryn Dominique Tan100% (1)

- View Loan Document PackageDokument8 SeitenView Loan Document PackageCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hiragana Katakana WorksheetDokument29 SeitenHiragana Katakana WorksheetRisa HashimotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internet and Education - Banking System of EducationDokument13 SeitenInternet and Education - Banking System of EducationCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Technology 2Dokument3 SeitenEducational Technology 2Cathryn Dominique Tan100% (1)

- Pediatrics NCLEX Review Pointers: Signs of Increased Intracranial PressureDokument14 SeitenPediatrics NCLEX Review Pointers: Signs of Increased Intracranial PressureCathryn Dominique Tan100% (1)

- Batas Pambansa BLG 232Dokument3 SeitenBatas Pambansa BLG 232Cathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Reformation & EducationDokument14 SeitenThe Reformation & EducationCathryn Dominique TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- JADWAL KBM TERBARU - Mulai 20 SeptemberDokument31 SeitenJADWAL KBM TERBARU - Mulai 20 SeptemberBull OakleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- SF1 - 2018 - Grade 1 - GRADE I-BDokument6 SeitenSF1 - 2018 - Grade 1 - GRADE I-BDOMINADOR PANOLINNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal UAS Bahasa Inggris Kelas 1 SD Semester 1 (Ganjil) Dan Kunci Jawaban PDFDokument5 SeitenSoal UAS Bahasa Inggris Kelas 1 SD Semester 1 (Ganjil) Dan Kunci Jawaban PDFAnitaSulmawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language Mapping of Santa Cruz Kindergarten ClassDokument6 SeitenLanguage Mapping of Santa Cruz Kindergarten ClassRey Bahillo RojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- LanguagesDokument5 SeitenLanguagesFrancis MajadasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mtb-Mle: (Mot Her Tongue-Based Mult I Lingual Educat Ion)Dokument42 SeitenMtb-Mle: (Mot Her Tongue-Based Mult I Lingual Educat Ion)Julhayda FernandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grading SystemDokument40 SeitenGrading SystemAldi RenadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- SF 1 School RegisterDokument2 SeitenSF 1 School RegisterByron DizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excuse Letter TubuananDokument4 SeitenExcuse Letter Tubuananma.ashleyavila04Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nest Chinese Name PronunciationDokument3 SeitenNest Chinese Name PronunciationHafid Tlemcen Rossignol PoèteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Di Yi KeDokument2 SeitenDi Yi KeJulia Dianne M. BustamanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Lengkap Mentor Dan Peserta Semua Jenjang 24 April 2021Dokument104 SeitenData Lengkap Mentor Dan Peserta Semua Jenjang 24 April 2021WulanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Vitae: Name: Bermas, Ryan R. Address: San Lorenzo Mauban, Quezon Mobile Number: 09950953107Dokument6 SeitenCurriculum Vitae: Name: Bermas, Ryan R. Address: San Lorenzo Mauban, Quezon Mobile Number: 09950953107Eliseo SorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mother Tongue - Iloko Grades 1-3Dokument43 SeitenMother Tongue - Iloko Grades 1-3Sheena MovillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curso de Chino Hojas de Practicas-2 PDFDokument86 SeitenCurso de Chino Hojas de Practicas-2 PDFBruce Der SchwarzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABLCS 2-2 - Daza - Actvity 7Dokument3 SeitenABLCS 2-2 - Daza - Actvity 7Jamel DazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPTDokument5 SeitenPPTChloe RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8010 Common Practice Analysis Sheet 2 Nov 12Dokument568 Seiten8010 Common Practice Analysis Sheet 2 Nov 12SK Business groupNoch keine Bewertungen

- 475 - Where Does Malay Come From? Twenty Years of Discussions About Homeland, Migrations and ClassificationDokument31 Seiten475 - Where Does Malay Come From? Twenty Years of Discussions About Homeland, Migrations and ClassificationanakothmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Vi - Preactivity - Literature in Central and Eastern VisayasDokument3 SeitenChapter Vi - Preactivity - Literature in Central and Eastern VisayasEl Cosanshin EguillonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Registered Support Organizations List as of July 2020Dokument225 SeitenRegistered Support Organizations List as of July 2020Mirsa Wahyu FajarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Find job applicant Realyn S. profileDokument2 SeitenFind job applicant Realyn S. profileAyessa NunagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tagalog As A Dominant Language PDFDokument22 SeitenTagalog As A Dominant Language PDFMYRLAN ANDRE ELY FLORESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bag-Ong Yánggaw: Ang Filipinong May Timplang Bisaya Sa Kamay NG Makatang Tagalog Na Si Rebecca T. AñonuevoDokument15 SeitenBag-Ong Yánggaw: Ang Filipinong May Timplang Bisaya Sa Kamay NG Makatang Tagalog Na Si Rebecca T. AñonuevoRandom MusicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting SHS Course ChoicesDokument6 SeitenFactors Affecting SHS Course ChoicesMichaella DometitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Listing 2020-2021Dokument396 SeitenStudent Listing 2020-2021Lorinel Mendoza100% (1)

- Format ModularDokument34 SeitenFormat Modular林艾利Noch keine Bewertungen

- Komunikasyon at PananaliksikDokument151 SeitenKomunikasyon at PananaliksikDanielle Faith Fulo100% (2)

- Surigaonon by MOONeraDokument6 SeitenSurigaonon by MOONerabraeewakefieldNoch keine Bewertungen

- I LocanoDokument2 SeitenI LocanoNiño Ronelle Mateo EliginoNoch keine Bewertungen