Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

R C T H C M E: Eflection and Ritical Hinking of Umanistic Are in Edical Ducation

Hochgeladen von

Karlina RahmiOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

R C T H C M E: Eflection and Ritical Hinking of Umanistic Are in Edical Ducation

Hochgeladen von

Karlina RahmiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

REFLECTION AND CRITICAL THINKING OF

HUMANISTIC CARE IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

Shu-Jen Shiau1,2 and Chung-Hey Chen3

1

School of Nursing, National Taipei College of Nursing, and 2Division of Nursing Education,

Medical Education Committee, Ministry of Education, Taipei, and 3College of Nursing,

Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

The purpose of this paper is to stress the importance and learning issues of humanistic care in

medical education. This article will elaborate on the following issues: (1) introduction; (2) reflection and critical thinking; (3) humanistic care; (4) core values and teaching strategies in medical

education; and (5) learning of life cultivation. Focusing on a specific approach used in humanistic

care, it does so for the purpose of allowing the health professional to understand and apply the

concepts of humanistic value in their services.

Key Words: critical thinking, humanistic care, medical education, reflection

(Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2008;24:36772)

INTRODUCTION

Humanistic care in the twenty-first century requires

reflective maturity, global perspectives, interdisciplinary, technical information, and comfort with ambiguity. Health professionals face challenges everyday

when offering their services to people. They know

what they know and do not know, and have alternative methods to make clinical decisions. Health

professionals also need to be reflective in the context

of patients, families, and communities. It is very

important that health professionals are enabled to

be reflective, critical, flexible, and comfortable with

humanistic care [1]. In 1992, Carper regarded the various patterns of knowing as not mutually exclusive, as interrelated and interdependent [2]. By

focusing on the concept of humanistic care, health

Received: Apr 29, 2008

Accepted: Jul 30, 2008

Address correspondence and reprint requests to:

Dr Shu-Jen Shiau, 365, Ming Te Road, Peitou

112, Taipei, Taiwan.

E-mail: Shiau6@gmail.com

Kaohsiung J Med Sci July 2008 Vol 24 No 7

2008 Elsevier. All rights reserved.

professionals will be able to understand the core values

in their services.

From the significance of the reflective, multidimensional approach to humanistic care, we realize that

the health care arena is an extremely complex and

dynamic process. Therefore, there are many ways in

which humanistic care can be implemented in the care

of individuals, families, and communities. In addition, health professionals need humanistic care to

provide their services as a multidimensional reflective experience. Self-reflection, history, legal and ethical issues, spirituality, culture, family, media, group,

evidenced-based practice, economics, and health policy

can all affect humanistic care, and need to be critically thought about as an important process to consider throughout humanistic care [1]. Being aware of

the possibilities allows for fluidity and flexibility in

thinking that the health professional needs. Health

professionals touch the lives of people in every situation from birth to death, in health and illness. Care is

a human response to a particular situation. To allow

for diversity of ideas, health professionals write from

their own experience, use their own case studies, and

develop their own thoughts on the caring situation.

367

S.J. Shiau and C.H. Chen

How do people respond to issues surrounding

sickness and health? As a teacher thinking about how

to teach in the 21st century, it is wise to understand

the changes in approaches to education. With regard

to health care education from the 20th to 21st century

[3], here are some strategies: (1) the dreaded lecture;

(2) small group learning; (3) problem-based learning;

(4) case study; (5) reflecting on reflection; (6) role

playa stage of learning; (7) creative activities; (8)

simulationtransforming technology into teaching;

(9) experience learning exercises; (10) blended and

e-learning; (11) self-directed study; and (12) applying

strategies to practice.

This article will elaborate on the following issues:

reflection and critical thinking; humanistic care; core

values and teaching strategies in medical education;

and learning of life cultivation.

REFLECTION AND CRITICAL THINKING

ODonnell et al defined self-reflection as an examination of ones own thoughts and feelings, and requires

maturity and a desire to know who you are [4]. The

genesis for humanistic care began when we taught

education; self-reflection was used to develop a nature

of knowledge needed for medical practice. Knowledge

lies embedded within everyday life experiences, and

how to transform daily experience to the answer we

need is self-reflection. Self-reflection asks that we look

at ourselves and transform our everyday life experience

to knowledge that can then be applied in humanistic

care [1]. As a result, those intellectual and affective

activities in which individuals engage to experience

will lead to new understandings and appreciations [5].

When expressing care, health professionals need

to understand that the process requires looking inward

at ones own self, then outward at the world around

them, and then back in again. We describe who we

are, where we are from, our education, and relate

how these experiences have shaped our philosophy

and care for others. During the period of reflection,

we can share and recognize that reflection is the process

of looking back at an experience or situation and analyzing it. It is an opportunity to question our values,

beliefs, and assumptions [6]. We each draw from our

intra- and interperceptual experiences; however, it is

better to have adequate action with self-reflection and

awareness of what the self brings to the humanistic

368

care process. Reflection can facilitate the development

of encouraging inquiry and autonomy, acknowledging

feelings, increasing self-awareness and understanding, and enhancing professional practice. Witmer

described these steps in reflection: (1) look back; (2)

elaborate and describe; (3) analyze outcomes; (4)

revise approach; and (5) new trial [7].

Critical thinking was defined by Campbell as

open-minded reasoning; use of intellectual standards

of reasoning including, clarity, depth and breadth of

understanding and relevance of information to a situation, and questioning of assumptions and biases

[8]. In addition, critical thinking gives us a way to

look at the world and, thus, support the work we do.

According to Paul and Nosichs theory, critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively

and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing,

synthesizing, and evaluating information gathered

from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, and communication, as a guide to

belief and action [9].

There are five elements to critical thinking: thought;

macro-abilities; traits of the mind; affective dimensions; and intellectual standards. Further, there are

six processes that can improve critical thinking ability:

experiential learning; reflection; advanced questioning technique; computer assisted instruction; concept

mapping; and case method. Combining nursing theoretical work with critical thinking, we can find that

critical thinking is essential in this era of theory utilization because theory provides the basis for nurses

knowledge as well as a structure to guide caring

actions [10].

HUMANISTIC CARE

In the 21st century, health professionals are expected

to provide more than medical care, going more in the

direction of holistic care. Medicine can be not only a

science but can also be more humanistic by assisting

people to seek their own value of life and achieve

self-actualization and self-healing. Maslows hierarchy of human needs (Figure 1) provides the profound

map to understand humanistic desires.

Looking into Watsons theory [11], humanistic

caring is a fundamental belief in the internal power

of the care process to produce growth and change for

people. Watson believed that faithhope can facilitate

Kaohsiung J Med Sci July 2008 Vol 24 No 7

Humanistic care in medical education

Self-transcendent

Selfactualization

Esteem and self-esteem

Love and belonging

Safety and security

Physiological needs: air, food, water, sleep, sex, etc.

Figure 1. Maslows hierarchy of human needs.

the promotion of holistic nursing and positive health.

Watsons 10 care factors are: (1) formation of a

humanisticaltruistic system of values; (2) instillation

of faithhope; (3) cultivation of sensitivity to ones

self and to others; (4) development of a helpingtrust

relationship; (5) promotion and acceptance of the

expression of positive and negative feelings; (6) systematic use of the scientific problem-solving method

for decision-making; (7) promotion of interpersonal

teachinglearning; (8) provision of a supportive, protective, and/or corrective mental, physical, sociocultural, and spiritual environment; (9) assistance with

gratification of human needs; and (10) allowance for

existentialphenomenological forces. Watson defined

each of these care factors and gave examples of what

nurses can ask themselves critically with regard to each

factor. For example, for: (1) formation of a humanistic

altruistic system of values: practice of loving-kindness

and equanimity in the context of caring-consciousness.

The questions you can ask yourself are: Who is this

person? Am I open to participate in his/her personal

story? How am I being called to care? How ought I

to behave in this situation? For: (2) instillation of

faithhope: being authentically present and enabling

and sustaining the deep belief system and subjective

life world of self and the one-being-cared-for. The

questions you can ask yourself are: What does this

relationship mean to this patient? What health event

brought this person to the health facility? What information do I need to nurse this person? Can I imagine

what this experience is like? Can I encourage this

person to find faith/hope?

Applying Watsons perspective, when working

with others during times of despair, vulnerability

Kaohsiung J Med Sci July 2008 Vol 24 No 7

and the unknown, we are challenged to learn again,

to reexamine our own meaning of life and death [11].

A human-to-human act of caring within a given

moment becomes a basic foundation for facing our

humanity, uniting us and the cosmic energy of love.

Caring and compassionate acts of love beget healing

for self and others [12]. For Christians, humanism

means valuing life over material things, and to encourage ethics and moral values [13]. The sacrament of

reconciliation is considered: in relation to God, in

relation to my neighbor, in relation to myself [14].

Watsons human care theory projects a reverence for

the mysteries of life and an acknowledgment of lifes

spiritual dimensions. A health care professional who

is tuned in to lifes spiritual dimensions can express

care and help patients do the same by taking into

account patients spiritual needs; they have the ability

to understand their own spirituality and that of the

patient, family, and community. Chen addresses values, religious beliefs, and what is meant by spirituality and humanistic care in nursing [13].

CORE VALUES AND TEACHING STRATEGIES

IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

In Lewis Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great

University Forgot Education, the core value of education was emphasized [15]. The World Federation for

Medical Education has listed the core areas in the

medical curriculum as: (1) basic biomedical sciences;

(2) basic behavioral and social sciences; (3) humanities;

(4) general clinical skills; (5) clinical decision-making

skills; (6) communication abilities; and (7) medical

ethics. Global Minimum Essential Requirements offer

seven educational outcomecompetence domains: (1)

professional values, attitudes, behavior and ethics; (2)

scientific foundation of medicine; (3) communication

skills; (4) clinical skills; (5) population health and

health systems; (6) management of information; and

(7) critical thinking and research [16]. The Taiwan

Medical Accreditation Council also emphasizes these

core values of medical education and practice.

The philosophy of the School of Nursing,

McMaster University, is our favorite: nursing is a scientific and humanistic activity of professional caring.

The McMaster model of nursing education defines

the learner and facilitator as persons made up of body,

mind and spirit, influenced by life meaning, values

369

S.J. Shiau and C.H. Chen

and beliefs [17]. The Taiwan Nursing Accreditation

Council identified different professional core values of universities and colleges. For universities, they

are: (1) critical thinking and reasoning; (2) general

clinical skills; (3) basic biomedical science; (4) communication and team work capability; (5) caring; (6)

ethics; (7) accountability; and (8) life-long learning.

For colleges, they are: (1) general nursing skills; (2)

basic medical sciences; (3) respecting life and caring;

(4) identifying and solving problems; (5) professional conduct and teamwork capability; and (6) selfdevelopment [18].

There has been a great growth in knowledge and

research with regard to education, resulting in many

theories of how to learn. Some of them have been

grouped under schools of thought as follows:

Behaviorist. This theory presents transactional

analysis theory and considers that positive and

negative strokes to self-esteem have great impact

on learning.

Cognitivist. Here are many theorists who consider

that in terms of skills acquisition, a learner moves

from being a novice to being a potential expert.

Humanist. Learners are people; we learn from

each other and have different driving forces and

life problems.

Reflectionist. Focus is on what goes on inside an

individuals head, their thinking. Due regard is

given to the idea that we can use this to identify

learning, in a reflective way [3].

In relation to learning styles, there are several models:

Kolbs model. Kolb, who considered the different

processes of concrete and abstract thinking,

together with experimentation and observation.

There are four categories of learner; a learner will

have a preferred leaning towards one of the categories: diverger, converger, assimilator, accommodator.

Honey and Mumfords model. In this theory, students are categorized as activists, pragmatists,

reflectors or theorists.

VARK model. These models consider the cognitive processes (visual, auditory, reading/writing,

kinesthetic); students will have a preference for

one to enhance learning.

Neurolinguistic programming. Helps provide reference to individuals who think with pictures, sound

and feeling. Also, the other senses of taste, touch

and smell are connected with memories; therefore,

370

learning may be improved if these aspects are also

incorporated into the teaching sessions.

In relation to teaching styles, there are also several

models:

Robins and Greenwood. They describe two different teaching stylesconservative and progressive.

Gilmartins model. There are four styles. Type 1 is

a didactic style, type 2 is similar to type 1 but

includes experiential activities, type 3 favors

student-centered facilitation, and type 4 focuses

on creative approaches.

Grashas model. This reflects the activity pursued

by the person at the front of the class. There are

five categories: expert, formal authority, personal

model, facilitator, delegator.

LEARNING OF LIFE CULTIVATION

Caring concern is the core of nursing. Quality medical care is patient-centered and based on safety,

effectiveness, adequacy, efficiency, and equality. The

incorporation of care, concern and compassion (3Cs)

into nursing education is the major subject we would

like to discuss [19]. The 3Cs are the mission of the

School of Nursing, Catholic Fu-Jen University in

Taiwan. In research into the 3Cs applied in nursing

education, Shiau demonstrated that the relevant concept and strategies embracing the 3Cs of nursing

education can develop into the learning of life cultivation through which are included three elements:

growing experience; lifes meaning and value; and

professional services (Figure 2) [20].

Lifes meaning

and value

3Cs

Professional

services

Growing

experience

Figure 2. Learning of life cultivation.

Kaohsiung J Med Sci July 2008 Vol 24 No 7

Humanistic care in medical education

Shiau et al reported on the phenomena of offering

and receiving 3C experiences of life, based on emphasizing the cultivation of life education in nursing

education. Their findings demonstrated that utilization of the 3Cs to offer and receive experiences

of bitter events can transform the bitterness into a

learning mechanism of love and wisdom. Their results provide important references for the continued

development of the fundamental theory and strategies of life education in nursing, and the enhancement of in-depth self understanding and service to

others [21]. In another report, Shiau et al studied

one teacher and 11 students on a Leadership and

Management course. They participated in weekly

discussions of the learning experience associated

with the clinical practicum. Content analysis revealed four main problems: individual characteristics of

patients and families and their stress adaptation on

bio-psycho-spirits; humanity-centered procedures

and equipment; suffering related to nursing working context; and nurse growth to be a whole person. The following problem resolutions were found:

offering care in respecting the individual characteristics of patients and their families, and stressing

care in stress adaptation of bio-psycho-spirits; formulating and planning humanity-centered nursing

procedures and equipment; cultivating an understanding and supportive nursing administration culture; and constructing a developing program of

knowledge, attitude and behavior for self and professional development [22].

A 3Cs Learning Group was developed to promote

nursing leaders adoption of the concepts and competencies of the 3Cs in nursing administration in

order to more firmly root nursing care in care for the

human being [23]. The findings demonstrated the

effectiveness of the mentors facilitation concepts

and skills, and the dynamic operation of the group

process (Figure 3). The results can provide information and suggest techniques to assist nursing leaders

in 3Cs learning groups to promote self growth and

encourage nursing staff to enhance service advocacy

and quality [24].

The results of this series of research studies with

the incorporation of 3Cs will develop a humanitarian

perspective, focused on patients, nurses, and the

working environment perspective, which will more

closely meet the core values of caring concern and

medical quality.

Kaohsiung J Med Sci July 2008 Vol 24 No 7

Work

Individual

Group

Figure 3. Dynamic operation of the group process.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

Lewenson SB, Truglio-Londrigan M. Decision-making

in Nursing. MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2008.

Carper BA. In: Kikuchi JE, Simmons H, eds.

Philosophical Inquiry in Nursing: An Application. London:

Sage Publications, 1992.

Woodhouse J. Strategies for Healthcare Education.

Radcliffe: Oxon, 2007.

ODonnell JP, Lewenson SB, Keith-Anderson K. Who

am I? Teaching nurse practitioner students to develop

self-reflective practice. In: Crabtree MK, ed. Teaching

Clinical Decision-making in Advanced Nursing Practice.

Washington, D.C.: National Organization of Nurse

Practitioner Faculties, 2000.

Boud D, Keogh R, Walker D. Reflection: Turning Experience Into Learning. New York: Nichols Pub Co, 1985.

College of Nurses of Ontario Professional Profile. Ontario:

University of McMaster, Toronto, 1996.

Witmer D. Making the choice. What reflective practice

option is best for me? College Communique 1997;22:

158.

Campbell ET. Meeting practice challenges via a clinical

decision-making course. Nurse Educ 2004;29:1958.

Paul RW, Nosich GM. Practice for the National Assessment

of Higher-order Thinking, Revised Version. Washington,

DC: United States Department of Education, Office of

Education Research and Improvement, National Center

for Education Statistics, 1991.

Alligood MR, Tomey AM. Nursing Theory Utilization

and Application, 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2006.

Watson J. Love and caring ethics of face and hand

an invitation to the heart and our deep humanity.

Nurs Adm Q 2003;27:197202.

Sourial S. An analysis and evaluation of Watsons

theory of human care. J Adv Nurs 1996;24:4004.

Chen LC. Professional outcome/goals of Christian

humanism. Profile Letter, 2007.

371

S.J. Shiau and C.H. Chen

14. World Youth Day. Young People at Prayer. Novalis.

Ottawa: Saint Paul University, 2002.

15. Lewis HR. Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great

University Forgot Education. MA: Public Affairs, 2007.

16. Chen ZU. The Current, Integrated, and Perspective of the

UGY Educational System. Taiwan Association of Medical

Education 96th Annual Meeting and Conference,

National Taiwan University, College of Medicine,

Taipei, 2007.

17. Shiau SJ. Facultys Self Bio-spirituality and Reflection in

PBL. The 3rd Asia-Pacific Conference on Problem-Based

Learning (PBL) in Health Sciences, PBL: Global

Trends in Medical Education, Chang Gung University,

Taiwan, 2002.

18. Taiwan Nursing Accreditation Council. The

Accreditation Manual of the Taiwan Nursing Accreditation

Council. Taipei: Higher Education Evaluation and

Accreditation Council of Taiwan, 2007.

372

19. Shiau SJ, Chiaug YT, Huang YC, et al. The life cultivation of nursing education touched by care, concern and

compassion. J Med Educ 2006;10:17.

20. Shiau SJ. Learning of life cultivation through nursing

education. J Nurs 2007;54:238.

21. Shiau SJ, Shiau SM, Chang YM, et al. Learning to offer

and receive experiences in life: the mechanism of transforming suffering into love and wisdom. Fu-Jen J Med

2006;4:17786.

22. Shiau SJ, Chang YM, Wei LL, et al. Incorporation of

care, concern, and compassion into problem analyzing

and resolving in nursing. J Health Sci 2006;8:3645.

23. Shiau SJ, Lo SC, Wei LL, et al. The phenomena of the

3C learning group for nursing leaders. J Evid Based

Nurs 2006;3:1626.

24. Shiau SJ, Fang YU, Lo HM. To Explore the Leading

Knowledge of Spiritual Growing Group for Nursing

Faculty. [Unpublished, 2007]

Kaohsiung J Med Sci July 2008 Vol 24 No 7

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- AP Physics Inquiry Based Lab ManualDokument348 SeitenAP Physics Inquiry Based Lab ManualKarlina Rahmi100% (1)

- New Reiki BeneficioDokument79 SeitenNew Reiki BeneficioMonica Beatriz AmatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Watson's Theory of Caring ScienceDokument44 SeitenWatson's Theory of Caring ScienceAyyu SandhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Similarities and differences of ten nursing theoriesDokument13 SeitenSimilarities and differences of ten nursing theoriesleiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top 7 Characteristics and Qualities of A Good TeacherDokument3 SeitenTop 7 Characteristics and Qualities of A Good TeacherDayang Sadiah Hasdia100% (1)

- Science Lower Secondary 2013Dokument39 SeitenScience Lower Secondary 2013tanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline of TopicsDokument202 SeitenOutline of TopicsMaricel AlbanioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answers To How To Master Your Life - Scribd DR LENDokument11 SeitenAnswers To How To Master Your Life - Scribd DR LENJackie A Paulson100% (4)

- PYC1501Dokument43 SeitenPYC1501Anonymous fFqAiF8qYg100% (2)

- Nursing Theories and Theorists Endterm Topic 01Dokument25 SeitenNursing Theories and Theorists Endterm Topic 01CM PabilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personality PsychologyDokument101 SeitenPersonality PsychologyAnonymous gUjimJKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jean WatsonDokument44 SeitenJean WatsonRon Opulencia100% (1)

- DNP 800 Philosophy of NursingDokument7 SeitenDNP 800 Philosophy of Nursingapi-247844148Noch keine Bewertungen

- Development of Nursing TheoriesDokument6 SeitenDevelopment of Nursing TheoriesBasil Hameed AmarnehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics of care and conscientious objectionVon EverandEthics of care and conscientious objectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy of Nursing EducationDokument5 SeitenPhilosophy of Nursing Educationamit50% (2)

- Unit 3 Goals of Nursing and Related ConceptsDokument40 SeitenUnit 3 Goals of Nursing and Related Conceptssyedmanzoor171Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jean Watson's Philosophy and Science of CaringDokument31 SeitenJean Watson's Philosophy and Science of CaringFariz AkbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theory AssignmentDokument5 SeitenNursing Theory AssignmentAfz MinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Arts LO Module 2Dokument7 SeitenNursing Arts LO Module 2AmberpersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jean Watson TheoryDokument5 SeitenJean Watson Theorykamaljit kaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intoduction To Nursing EthicsDokument17 SeitenIntoduction To Nursing EthicsAnjo Pasiolco CanicosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical Foundations of Nursing Theories ExplainedDokument4 SeitenTheoretical Foundations of Nursing Theories Explainedmaria linda agusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Will, End-Oflife Of: Kron L - Nllons. IivingDokument12 SeitenWill, End-Oflife Of: Kron L - Nllons. IivingRoxanne Ganayo ClaverNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Educational Psychology PDokument6 SeitenIntroduction To Educational Psychology Ppuji chairu fadhilahNoch keine Bewertungen

- TFN WatsonDokument24 SeitenTFN WatsonChen Kae BaptistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FUNDADokument6 SeitenFUNDARichard Castada Guanzon Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Comportment - Mne 625Dokument18 SeitenEthical Comportment - Mne 625api-312894659Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jean Watson Theory of Human CaringDokument18 SeitenJean Watson Theory of Human CaringWithlove AnjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jean WatsonDokument22 SeitenJean WatsonIsaiah PascuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 3. PH 51Dokument14 SeitenUnit 3. PH 51Marielle UberaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humanistic Learning Theory Focus on Feelings, Self-ConceptDokument5 SeitenHumanistic Learning Theory Focus on Feelings, Self-ConceptNikki RicafrenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Watson's Theory of Human Caring: A Holistic Approach to NursingDokument20 SeitenWatson's Theory of Human Caring: A Holistic Approach to NursingAra Jean AgapitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay Caring - Rizka Noviola Hardita - 2011313008Dokument3 SeitenEssay Caring - Rizka Noviola Hardita - 2011313008RizkaanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical FrameworkDokument6 SeitenTheoretical FrameworkJenny Agustin FabrosNoch keine Bewertungen

- n5303 Theoretical Foundations of Nursing Nursing EducationDokument8 Seitenn5303 Theoretical Foundations of Nursing Nursing Educationapi-730690402Noch keine Bewertungen

- Subject: Foundations of Nursing Masterand: Graziella A. Raga, R.N. Instructor: Lynn de Veyra, R.N., M.A.NDokument4 SeitenSubject: Foundations of Nursing Masterand: Graziella A. Raga, R.N. Instructor: Lynn de Veyra, R.N., M.A.NJose Van TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity #06Dokument9 SeitenActivity #06Katherine HernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIDWIFERY THEORIESDokument38 SeitenMIDWIFERY THEORIESAlana CaballeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2 NTDokument32 SeitenUnit 2 NTnaveedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Education Care Delivery Model-Nicky ReedDokument7 SeitenHealth Education Care Delivery Model-Nicky Reedapi-215994182Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theory Resource NetDokument10 SeitenNursing Theory Resource NetMelvin DacionNoch keine Bewertungen

- TFN ReviewerDokument36 SeitenTFN Revieweryes noNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundametal of NursingDokument25 SeitenFundametal of Nursingmahmoudmustapha93Noch keine Bewertungen

- Coun 513 MC-SJC Theory PaperDokument21 SeitenCoun 513 MC-SJC Theory Paperapi-282872818Noch keine Bewertungen

- Health Education S2ikmDokument22 SeitenHealth Education S2ikmRahmat HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLARIFYING THE DISCIPLINE OF NURSING AS FOUNDATIONAL - J Watson - 2017Dokument2 SeitenCLARIFYING THE DISCIPLINE OF NURSING AS FOUNDATIONAL - J Watson - 2017Nuno FerreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy and Science of Caring Jean Watson'sDokument27 SeitenPhilosophy and Science of Caring Jean Watson'sconcep19Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 3 (Overview of Nursing Theories)Dokument36 SeitenLecture 3 (Overview of Nursing Theories)Safi UllahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jean Watson - Philosophy & Caring TheoryDokument12 SeitenJean Watson - Philosophy & Caring Theorydorothy kageni100% (1)

- Caring of Nursing: PreliminaryDokument8 SeitenCaring of Nursing: PreliminaryRosdiyanti sinagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- hs420 Document l02-TheoryinHealthPromotionResearchandPracticepp93-106Dokument13 Seitenhs420 Document l02-TheoryinHealthPromotionResearchandPracticepp93-106liz gamezNoch keine Bewertungen

- TFN Module 2 (Topic 5-6)Dokument35 SeitenTFN Module 2 (Topic 5-6)grapenoel259Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theories GuideDokument15 SeitenNursing Theories Guideapi-532304340Noch keine Bewertungen

- NCM (Assignment)Dokument2 SeitenNCM (Assignment)Jacky Clyde EstoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCM 100 (TFN) Reminder: Assessment / Evaluation Should Be Done Every After Chapter/lessonDokument5 SeitenNCM 100 (TFN) Reminder: Assessment / Evaluation Should Be Done Every After Chapter/lessonLesly Justin FuntechaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TFN ReviewerDokument16 SeitenTFN ReviewerLunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept Note 1Dokument22 SeitenConcept Note 1AMIR LADJANoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric Nursing Theories and ModelsDokument31 SeitenPediatric Nursing Theories and ModelsLuthi PratiwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- TFN SES 3 - Chap8 - 9Dokument54 SeitenTFN SES 3 - Chap8 - 9Prince Charles AbalosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical Basis of Community Health Nursing-1Dokument49 SeitenTheoretical Basis of Community Health Nursing-1Sri WahyuniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - What Is PhilosophyDokument9 Seiten1 - What Is PhilosophyNashwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- NURSING CONCEPTS Exam GuideDokument24 SeitenNURSING CONCEPTS Exam Guide2016114427Noch keine Bewertungen

- DAY 2 (3 Hours) - Knowledge Development and Nursing ScienceDokument14 SeitenDAY 2 (3 Hours) - Knowledge Development and Nursing ScienceGlady ApitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical Foundations of Community Health Nursing PracticeDokument30 SeitenTheoretical Foundations of Community Health Nursing Practicemaeliszxc kimNoch keine Bewertungen

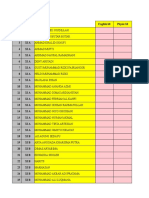

- 17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Dokument28 Seiten17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 Sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 5Dokument28 Seiten03 Sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 5Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 1Dokument21 Seiten06agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 1Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic in Education PDFDokument281 SeitenBasic in Education PDFSivakumar AkkariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fraenkel and WallenDokument8 SeitenFraenkel and WallenStephanie UmaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 3Dokument28 Seiten20agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 3Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Dokument28 Seiten17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- M. ThoyibiDokument22 SeitenM. ThoyibiKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 142 320 1 SMDokument9 Seiten142 320 1 SMKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 1 Mar 31Dokument3 Seiten1 1 Mar 31Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pembelajaran Mata Kuliah Pendidikan Kebudayaan Daerah Untuk Meningkatkan Kreatifitas MahasiswaDokument11 SeitenPembelajaran Mata Kuliah Pendidikan Kebudayaan Daerah Untuk Meningkatkan Kreatifitas MahasiswaKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 132 300 1 SMDokument9 Seiten132 300 1 SM085646528013Noch keine Bewertungen

- UNICEF Education StrategyDokument3 SeitenUNICEF Education StrategyKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 124 284 1 SMDokument8 Seiten124 284 1 SMKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812041535 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812041535 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- OPTIMIZING LEARNING ACHIEVEMENTDokument10 SeitenOPTIMIZING LEARNING ACHIEVEMENTKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MarkhamahDokument1 SeiteMarkhamahShandy AgungNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812040414 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812040414 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hubungan Kecocokan Antara Tipe Kepribadian Dan Model Lingkungan Belajar Dengan Motivasi Belajar Pada Mahasiswa PGSD Universitas Achmad Yani BanjarmasinDokument7 SeitenHubungan Kecocokan Antara Tipe Kepribadian Dan Model Lingkungan Belajar Dengan Motivasi Belajar Pada Mahasiswa PGSD Universitas Achmad Yani BanjarmasinKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Conference On Education and Educational Psychology (ICEEPSY 2012)Dokument8 SeitenInternational Conference On Education and Educational Psychology (ICEEPSY 2012)Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812037135 MainDokument7 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812037135 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812040980 MainDokument12 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812040980 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812044485 MainDokument10 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812044485 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defining and Measuring Critical Thinking in EngineeringDokument7 SeitenDefining and Measuring Critical Thinking in EngineeringKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812041006 MainDokument9 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812041006 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812040694 MainDokument10 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812040694 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of Critical Thinking On Pupils' Development and at The Level of Didactic ActivitiesDokument5 SeitenThe Influence of Critical Thinking On Pupils' Development and at The Level of Didactic ActivitiesKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812037512 MainDokument9 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812037512 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prospective Teachers' Evaluations in Terms of Using Reflective Thinking Skills To Solve ProblemsDokument6 SeitenProspective Teachers' Evaluations in Terms of Using Reflective Thinking Skills To Solve ProblemsKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnostic Examination InsightsDokument4 SeitenDiagnostic Examination InsightsMary Jane BaniquedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subject-Verb Agreement RulesDokument1 SeiteSubject-Verb Agreement RulesMohd AsyrafNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical History of Western PhilosophyDokument7 SeitenA Critical History of Western PhilosophymahmudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Path Fit RefDokument2 SeitenPath Fit RefMa. Roycelean PascualNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patient Communication PDFDokument16 SeitenPatient Communication PDFraynanthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLL - MTB 3 - Q2 - Catch Up ActivityDokument3 SeitenDLL - MTB 3 - Q2 - Catch Up ActivityHazel Israel BacnatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypnagogia - Peter SchwengerDokument12 SeitenHypnagogia - Peter SchwengerCACOETHES SCRIBENDI100% (1)

- Year 5 Simplified SowDokument34 SeitenYear 5 Simplified SowiqadinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contoh Extended AbstractDokument8 SeitenContoh Extended Abstractbintangabadi_techNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raquel's Daily RoutineDokument4 SeitenRaquel's Daily RoutinejamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resolve Conflicts Using Negotiation & MediationDokument16 SeitenResolve Conflicts Using Negotiation & MediationKrishnareddy KurnoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 The Poverty of The Stimulus ArgumentDokument45 Seiten10 The Poverty of The Stimulus ArgumentsyiraniqtifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technology As Student's Coping Mechanism For Stress and PressureDokument17 SeitenTechnology As Student's Coping Mechanism For Stress and PressureKaye Angelique DaclanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Ethics Short TestDokument1 SeiteBusiness Ethics Short TestJaaze AndresNoch keine Bewertungen

- AI in MarathiDokument2 SeitenAI in MarathiwadajkarvasurvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Form 1 SyllabusDokument9 SeitenEnglish Form 1 SyllabusSally LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading and Writing - Unit 5 - Tn1Dokument1 SeiteReading and Writing - Unit 5 - Tn1Romario JCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 29 Year 1Dokument3 SeitenWeek 29 Year 1Cikgu SyabilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Take a Position: Crafting an Argumentative Essay IntroductionDokument2 SeitenTake a Position: Crafting an Argumentative Essay IntroductionhomamunfatNoch keine Bewertungen

- For Teaching Sight Words!: Welcome To Perfect PoemsDokument5 SeitenFor Teaching Sight Words!: Welcome To Perfect PoemsroylepayneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpretative Sociology and Axiological Neutrality in Max Weber and Werner SombartDokument17 SeitenInterpretative Sociology and Axiological Neutrality in Max Weber and Werner Sombartionelam8679Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Rule Based Approach To Word LemmatizationDokument5 SeitenA Rule Based Approach To Word LemmatizationMarcos LimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Honeycomb ProblemDokument3 SeitenHoneycomb Problemapi-266350282Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction in Essay WritngDokument3 SeitenIntroduction in Essay WritngJAYPEE ATURONoch keine Bewertungen