Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1 s2.0 S1877042811003521 Main

Hochgeladen von

Karlina RahmiOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1 s2.0 S1877042811003521 Main

Hochgeladen von

Karlina RahmiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 15 (2011) 727730

WCES-2011

Problem solvers are better leaders: facilitating critical thinking

among educators through online education.

Katherine Greena *, Christine Jax a

a

Capella University, 225 South 6th Street, 9th Floor, Minneapolis, MN. 55402, USA

Abstract

The schools that new teachers and teacher leaders will be entering into in upcoming years will be diverse racially, culturally,

economically, and technologically. New educators and leaders must be prepared to enter this 21st Century workforce with an

understanding of these complexities, an ability to think critically and creatively, and be open to teaching and learning in ways and

situations they may not previously encountered. Problem-based learning and the use of case studies and eportfolios are

showcased as methods in which both online and face to face teacher education programs can best prepare new teachers and

teacher leaders in order to promote their critical thinking skills and ability to problem solve.

2011 Published by Elsevier Ltd. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license.

Keywords: Problem-Based learning; case study; online learning; teacher education

1. Introduction

Education is a multifaceted and an increasingly complicated process that demands high levels of knowledge,

ability, critical thinking and problem solving. As we move from a model of work-force development to one of

global collaboration, teachers have to expand their vision as well as their roles in order to mesh with the 21st Century

expectation of education and technology. Educational leaders must be prepared to guide their teachers and staff on a

path that has not necessarily been developed. Educational programs must focus on increasing student teachers

abilities to problem solve, use technology, and think critically because many issues they will encounter in the future

have not been anticipated and addressed in their studies.

Becoming a high quality teacher today means using appropriate technology, meeting students where they are

technologically, and understanding that the world is accessed differently among our learners. However, this type of

integration of technology with real classroom experiences will not be easy for many of our teachers. Often students

know much more about technology than do their teachers. They send podcasts to each other and refer to people who

email as old-fashioned, yet they have teachers who are satisfied to have a homepage and to have mastered the use

of PowerPoint, barely realizing that there is little difference between a chalkboard and PowerPoint to the receiver of

information, especially if the teacher is simply reading the information.

*Katherine Green. Tel.:(865) 335 9758

E-mail address: . katherine.green@capella.edu

18770428 2011 Published by Elsevier Ltd. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license.

doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.173

728

Katherine Green and Christine Jax / Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 15 (2011) 727730

At the same time, there are still many children in classrooms who do not have cell phones or computers at home,

much less the necessary applications and networks. This means that current and prospective teachers have to keep

current with technology and how to use it, while simultaneously relying on old ways of accessing information so as

not to create an insurmountable divide between the technological haves and have-nots. High quality educators have

to be adept in this complex world by being flexible, creative, and continuously learning. Teacher education and

teacher-leader programs must focus on these elements if they wish to produce graduates capable of this high quality.

One way in which these newer and high quality approaches are being shared is via the internet. Online education

is growing exponentially. Germain-Rutherford and Kerr (2008) suggest that it is one of the fastest growing areas in

education but they note simply assuming that because the course or program is online and uses current technology, it

is automatically designed to educate for the 21st Century is erroneous. Many programs have been put into an online

format with little thought as to how these courses now reflect best practices related to technology and learning.

When we do this the sage on the stage simply becomes the sage in the box, which leaves much to be desired in

quality (McDonald, 2002). However, online education does not have to be so limited and programs and classes can

entail so much more.

This paper presents a variety of instructional strategies and tools that can be employed online or face-to-face to

develop effective educational leaders through the use of case-based learning and problem-based learning (PBL).

Examples are given of research-based best practices in online education that promote critical thinking, action

inquiry, and reflective teaching.

The use of cases as a learning tool has long been utilized in education as a way to develop high quality teachers

and teacher-leaders. Using cases as a basis of learning is supported by many educators (Darling-Hammond, 2006;

Harris, Pineggar, and Teemant, 2005; Levin, He, and Robbins, 2006; Weiss, Kreider, Lopez, and Chatman, 2005) as

a means of immersing learners in the experience and thus allowing them to make higher levels of connections

between theory and practice. Using the online environment as a platform for cases also allows for a rich and varied

approach that can incorporate multiple ways of learning. A case is traditionally a written description of a problem

situation for which students are tasked with applying course-provided information towards solving the prescriptive

problem. The emphasis course designers and instructors place on the outcome or resolution to the problem reflect

the objectives of the learning (Bridges and Hallinger, 1999). To expand the learning experience, cases can be in

video or audio format, created by the instructor, or brought to the course by the learners and shared in a

collaborative fashion. These approaches promote utilizing a format that supports multiple ways of learning, present

varying world perspectives, is more authentic, and can also aid learners whose first language may not have been

English (Harris, Pineggar, and Teemant, 2005).

Another approach that supports the development of high quality teachers and teacher-leaders is that of problembased learning. PBL originated in medical education 40 years ago (Bridges and Hallinger, 1999) with its roots

deeply embedded in cognitive psychology (Weaver Hart, 1999). While cases are used within PBL, the difference is

that problem-based learning relies on a project approach and the problem is not always clearly articulated to

students. It is perhaps less prescriptive in many ways and students must practice their growing knowledge and

theory skills within the project through such tools as role-playing, written materials, archival data or other

approaches to gathering and presenting information as they would perhaps utilize when actually in the classroom or

performing administrative roles (Weaver Hart, 1999).

Ryan and Grieshaber (2005) state that a postmodern teacher education program must provide students with a

theoretical toolbox that can be used to view issues from a multitude of angles, including angles yet to be needed.

PBL offers an additional way to help students develop leadership skills that can maneuver these angles because it

encourages them to manage multiple meanings and develop strategies for critical action (Savin-Baden, 2000, p.

143). Bridges and Hallinger (1999) state that PBL is generally centered around three primary objectives: 1.

acquiring new knowledge, 2. developing life-long learning skills, and 3. acquiring insight into the emotional aspects

of leadership. The authors articulate further that the first objective in PBL provides opportunities for five types of

knowledge including; domain-specific, procedural, strategic, self, and practical wisdom. Thus an instructor can

Katherine Green and Christine Jax / Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 15 (2011) 727730

729

choose to emphasize such areas as theory application, group decision making, problem solving, and/or identifying

personal bias depending on the focus of the course.

The second objective clearly reflects the type of teacher or teacher-leader needed in the 21 st Century. A report by

the World Bank supports this notion: In the 21st century, workers need to be lifelong learners, adapting

continuously to changed opportunities and labor market demands of the knowledge economy (World Bank, 2002,

p. 9). The report goes on to state that learning is not a luxury and post-basic, lifelong learning is vital to people in all

countries of the world. Learning does not begin at enrollment in university and end upon graduation; rather learning

is built upon within the program and skills promoted that allow graduates to be successful in ongoing discovery

(Aspin, Chapman, Hatton and Sawano, 2001; Moreno, 2005).

Bridges and Hallingers (1999) third PBL objective focuses on the emotional side of leadership. They purport

this is often overlooked by authors in the field and yet is not an area that should necessarily be read about but rather

students need to enact and feel the emotions of leadership. Through PBL, students are able to take on leadership

roles and feel what it means to be a leader as opposed to a subordinate, (p. 2).

Researchers are documenting a growing trend between PBL and the use of information technology in learning.

Evidence suggests that online learning is particularly rich and lasting when students are self-directed and participate

in the learning process (Heppell & Ramondt, 1998) and this is a notion supported by PBL (Savin-Baden, 2000). This

self direction must start in the beginning of the process with students encouraged to frame the problem based on

their own current understandings not only of the theory and material but their life view. Online learning often draws

together a rich tapestry of students who hail from varied locations, cultures and educational or work backgrounds.

This wide range of learners necessitates the need for instructors to put aside their own prescriptive problem solving

steps and prompt students to frame problems within their own socio-cultural lens. Leithwood et al. (2005) write,

We need to be developing leaders with large repertoires of practices and capacity to choose from that repertoire as

needed, not leaders trained in the delivery of one ideal set of practices (p. 8). These practices are not to be gained

simply from immersion in theory or readings but must be reflected upon and then acted upon. Freire (1970) stated

that reflection alone does not produce change and thus actions must be taken after reflection. PBL in the online

learning environment offers multiple ways to both reflect and then act.

Using asynchcronous online discussions for instance, allow for ongoing group work that can be contextualized to

the specific population and thus allow for higher persistence, increased motivation, and higher learning outcomes

(Smith, 2005). Discussion has been a highly utilized teaching strategy throughout history (Brookfield, 1990;

Waltonen-Moore, Stuart, Newton, Oswald, and Varonis, 2006) and promotes critical thinking, problem solving,

knowledge building plus aids in creating a sense of engagement and social connectedness. Research has shown that

learners who are active in course discussions have been found to be more successful in the course (Valasek, 2001)

and thus this element of online education should be seen as a large element of the learning process.

As has been described, case-based learning and PBL are both valuable approaches to developing successful

teachers and teacher-leaders both in traditional face to face classes and those online. But in an age of growing

dependence on prescriptive education grounded in mandated outcomes, standards-based learning, and test-driven

programs, how do we not only engage and utilize these approaches but document and show the growth that is

happening. We know that effective leaders are developed when students are encouraged to view their life

experiences and studies as continuously informing and supporting each other. Covey (2004) and DiMarco (2005)

describe the old model of skills assessment and traditional assessment (standardized tests, applications, and

resumes) as fading away due to 21st Century needs of knowledge over skill. In the age of knowledge there is a focus

on intellectual capital, technological skills, plus personal and professional traits. These are best enhanced by PBL

which places a focus on information gathering and critical thinking. One method of promoting and capturing this

learning progression is through the use of dynamic electronic portfolios. These provide a means of shifting passivity

in learning to one of an active and engaged role as students are able to choose artifacts, reflect on how these

demonstrate competencies, and generally engage in advanced forms of critical and complex thinking (Johnson,

Mims-Cox, & Doyle-Nichols, 2006). Eportfolios can include multiple forms of artifacts ranging from traditional

papers to video to representational art. Audio recordings of segments of the PBL experience could also be captured

730

Katherine Green and Christine Jax / Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 15 (2011) 727730

as well as collaborative case assessments and problem solving scenarios. It is often impossible for an instructor to

envision the totality of type of documentation and keeping an open mind is vital to allowing this process of

assessment to remain focused on 21st Century knowledge needs (known and unknown). Doing so may allow for cocreation of new methodologies and approaches.

PBL is an ideal approach for developing programs for new teachers and educational leaders. The focus is on

active and engaged learning, critical thinking, problem analysis, and solution evaluation (Levin, 2001). Blending

these foci with best practices in online learning is essential as technology changes how the world communicates.

Understanding and being open to these newer approaches will help ensure we have educators who can help our

younger generations be more successful in their own journeys.

References

Aspin, D. & Chapman, J. (2001). International handbook of lifelong learning. London: Kluwar.

Bridges, E. & Hallinger, P. (1999). The use of cases in Problem-Based Learning. Journal of Cases in Educational Leadership, 2 (2), pp 1-6.

Brookfield, S.D. (1990). The skillful teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Covey, S. R. (2004). The eighth habit. New York: Free Press.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st -Century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57, 3, p.300-321.

DiMarco, J. Web Portfolio Design and Application.

Hershey, PA, USA: Idea Group Publishing, 2005. p 294.

http://site.ebrary.com.library.capella.edu/lib/capella/ 10103946&ppg=310

Freire, P. (197). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Seabury Press

Germain-Rutherford, A., Kerr, B. (2008). An inclusive approach to

online learning environments: Models and resources. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 9 (2), pp.64-85.

Harris, C., Pinnegar, S. & Temmant, A. (2005). The case for hypermedia video ethnographies: Designing a new class of case studies that

challenge teaching practice. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13, 1 p 141-155.

Heppell, S. & Ramondt, L. (1998). Online learningimplications for the university for industry; a preliminary case study report. Journal of

Education Through Partnership, 2 (2): 7-28.

Johnson, R., Mims-Cox, J., & Doyle-Nichols, A. (2006). Developing portfolios in education. Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage Publications

Leithwood, K., Seashore Louis, K. Anderson, S. & Wahlstrom, K. (2005). How leadership influences student learning. New York: Wallace

Foundation.

Levin, B. (2001). Energizing Teacher Education and Professional Development with Problem-Based Learning. Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development. Alexandria, VA.

McDonald, J. (2002). Is As good as face-to-face as good as it gets? Journal for Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6 (2), 10-23.

Moreno, J. M. (2005). Learning to teach in the knowledge society. World Bank. Retrieved Sept. 28, 2008 from;

http://www1.worldbank.org/education/lifelong_learning/documents_reports.asp

Ryan, S. & Grieshaber, S. (2005). Shifting from developmental to postmodern practices in Early Childhood teacher education. Journal of

Teacher Education, 56, 1 pp 34-46.

Savin-Baden, M. (2000). Problem-Based Learning in Higher Education: Untold Stories. Open University Press: Philadelphia.

Smith, R. (2005). Working with difference in online collaborative groups. Adult Education Quarterly. 55 (3). Pp 182-199.

Valasek, T. (2001). Student persistence in web-based courses: Identifying a profile for success. Retrieved October, 2, 2008, from Raritan Valley

Community College, Center for the Advancement of Innovative Teaching and Learning (CAITL) Web site:

http://www.raritanval.edu/departments/CommLanguage/full-time/valasek/MCF%20research.final.htm

Waltonen-Moore, S., Stuart, D., Newton, E., Oswald, R. & Varonis, E. (2006). From virtual strangers to a cohesive learning community: The

evolution of online group development in a professional development course. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education. 14 (2), pp.

287-311.

Weaver-Hart, A. (1999). Educational leadership: A field of inquiry and practice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 27 (3).

Pp 323-334.

Weiss, H., Kreider, H., Lopez, M., & Chatman, C. (Eds.). (2005). Preparing educators to involve families: From theory to practice. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

World Bank (2002). Summary of the Global Conference on Lifelong Learning. Retrieved September 28, 2008 from:

http://www1.worldbank.org/education/lifelong_learning/documents_reports.asp

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

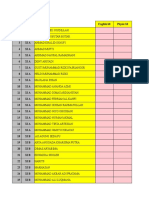

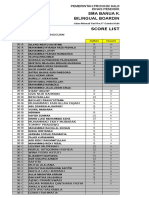

- 20agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 3Dokument28 Seiten20agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 3Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pembelajaran Mata Kuliah Pendidikan Kebudayaan Daerah Untuk Meningkatkan Kreatifitas MahasiswaDokument11 SeitenPembelajaran Mata Kuliah Pendidikan Kebudayaan Daerah Untuk Meningkatkan Kreatifitas MahasiswaKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Dokument28 Seiten17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 1Dokument21 Seiten06agst2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 1Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- M. ThoyibiDokument22 SeitenM. ThoyibiKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNICEF Education StrategyDokument3 SeitenUNICEF Education StrategyKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fraenkel and WallenDokument8 SeitenFraenkel and WallenStephanie UmaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 Sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 5Dokument28 Seiten03 Sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 5Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Dokument28 Seiten17sept2016 Evaluasi Minguaan Score List KLMP - 7Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 142 320 1 SMDokument9 Seiten142 320 1 SMKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 1 Mar 31Dokument3 Seiten1 1 Mar 31Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MarkhamahDokument1 SeiteMarkhamahShandy AgungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic in Education PDFDokument281 SeitenBasic in Education PDFSivakumar AkkariNoch keine Bewertungen

- AP Physics Inquiry Based Lab ManualDokument348 SeitenAP Physics Inquiry Based Lab ManualKarlina Rahmi100% (1)

- 132 300 1 SMDokument9 Seiten132 300 1 SM085646528013Noch keine Bewertungen

- 124 284 1 SMDokument8 Seiten124 284 1 SMKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812041535 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812041535 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- OPTIMIZING LEARNING ACHIEVEMENTDokument10 SeitenOPTIMIZING LEARNING ACHIEVEMENTKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812041006 MainDokument9 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812041006 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defining and Measuring Critical Thinking in EngineeringDokument7 SeitenDefining and Measuring Critical Thinking in EngineeringKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Conference On Education and Educational Psychology (ICEEPSY 2012)Dokument8 SeitenInternational Conference On Education and Educational Psychology (ICEEPSY 2012)Karlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hubungan Kecocokan Antara Tipe Kepribadian Dan Model Lingkungan Belajar Dengan Motivasi Belajar Pada Mahasiswa PGSD Universitas Achmad Yani BanjarmasinDokument7 SeitenHubungan Kecocokan Antara Tipe Kepribadian Dan Model Lingkungan Belajar Dengan Motivasi Belajar Pada Mahasiswa PGSD Universitas Achmad Yani BanjarmasinKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812044485 MainDokument10 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812044485 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812040980 MainDokument12 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812040980 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812040414 MainDokument8 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812040414 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812040694 MainDokument10 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812040694 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812037512 MainDokument9 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812037512 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of Critical Thinking On Pupils' Development and at The Level of Didactic ActivitiesDokument5 SeitenThe Influence of Critical Thinking On Pupils' Development and at The Level of Didactic ActivitiesKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S1877042812037135 MainDokument7 Seiten1 s2.0 S1877042812037135 MainKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prospective Teachers' Evaluations in Terms of Using Reflective Thinking Skills To Solve ProblemsDokument6 SeitenProspective Teachers' Evaluations in Terms of Using Reflective Thinking Skills To Solve ProblemsKarlina RahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Digital Storytelling Night Lesson PlanDokument6 SeitenDigital Storytelling Night Lesson Planapi-397843699Noch keine Bewertungen

- Potential Viva QuestionsDokument7 SeitenPotential Viva QuestionsJesús Rodríguez RodríguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Popular Versus Scholarly Sources WorksheetDokument6 SeitenPopular Versus Scholarly Sources WorksheetTanya AlkhaliqNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISTQB Agile TesterDokument22 SeitenISTQB Agile TestertalonmiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board Name Correction DecisionsDokument2 SeitenBangladesh Madrasah Education Board Name Correction DecisionsImamNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Elderly Retirement Homes InPH Ver2 With CommentsDokument20 SeitenDe Elderly Retirement Homes InPH Ver2 With CommentsgkzunigaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Bulletin No. 10, S. 2020: Associate Justice and 2020 Bar Examinations ChairDokument9 SeitenBar Bulletin No. 10, S. 2020: Associate Justice and 2020 Bar Examinations ChairjamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mohamed Salah (Chemist)Dokument1 SeiteMohamed Salah (Chemist)mohamedsalah2191999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Glenwood High School Elite Academic Academy Cambridge Private Candidate Registration Form-2019Dokument1 SeiteGlenwood High School Elite Academic Academy Cambridge Private Candidate Registration Form-2019RiaanPretoriusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lincoln University - International Student GuideDokument80 SeitenLincoln University - International Student GuidebhvilarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Implementation of Anti-Smoking Ordinance ThesisDokument11 SeitenImplementation of Anti-Smoking Ordinance ThesisBOLINANoch keine Bewertungen

- Norman StillmanDokument3 SeitenNorman StillmanIsmaeel AbdurahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- J218EMPLOYDokument3 SeitenJ218EMPLOYsyed saleh nasirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activities Binder Assignment 1Dokument3 SeitenActivities Binder Assignment 1api-659087537Noch keine Bewertungen

- Klimaks Midterm Practice Questions MPSDDokument3 SeitenKlimaks Midterm Practice Questions MPSDSyaifa KarizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Analysis and ExhibitsDokument158 SeitenCase Analysis and ExhibitsOwel Talatala100% (1)

- Ukrainian Welcome Kit English Version 1654309261Dokument9 SeitenUkrainian Welcome Kit English Version 1654309261License To CanadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Max Van Manen - The Tact of Teaching - The Meaning of Pedagogical Thoughtfulness-State University of New York Press (1991)Dokument251 SeitenMax Van Manen - The Tact of Teaching - The Meaning of Pedagogical Thoughtfulness-State University of New York Press (1991)Antonio Sagrado LovatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV EnglishDokument3 SeitenCV Englishmaria kristianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teachers Guide Sim City 3000Dokument63 SeitenTeachers Guide Sim City 3000FelipilloDigitalNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE Elec 101 - Module 1Dokument12 SeitenGE Elec 101 - Module 1Alfie LariosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan 3 Fairy Tale Narration - Clinical 429Dokument6 SeitenLesson Plan 3 Fairy Tale Narration - Clinical 429api-176688637Noch keine Bewertungen

- BASIC STUDY MANUAL Compiled From The Works of L. RON HUBBARDDokument83 SeitenBASIC STUDY MANUAL Compiled From The Works of L. RON HUBBARDsirjsslutNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAP719 Fundamentals of Human FactorsDokument38 SeitenCAP719 Fundamentals of Human Factorsbelen1110Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aiden Tenhove - ResumeDokument1 SeiteAiden Tenhove - Resumeapi-529717473Noch keine Bewertungen

- I Day SpeechDokument2 SeitenI Day SpeechRitik RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opportunities and Obstacles1Dokument24 SeitenOpportunities and Obstacles1Mhing's Printing ServicesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 7 (AoL2)Dokument7 SeitenModule 7 (AoL2)Cristobal CantorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Education: Budget of Work in Grade 7 EnglishDokument2 SeitenDepartment of Education: Budget of Work in Grade 7 EnglishMarjorie Nuevo TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trends in African TheologyDokument12 SeitenTrends in African TheologySunKing Majestic Allaah100% (1)