Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Shoulder Dislocations

Hochgeladen von

khalidaharwinCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Shoulder Dislocations

Hochgeladen von

khalidaharwinCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CHAPTER 196

SHOULDER DISLOCATIONS

Jeffrey V. Smith

Dislocations of the shoulder are quite common. Approximately 50%

of shoulder injuries in the emergency department are dislocations.

Anterior dislocations are far more common than posterior disloca

tions. The four types of anterior dislocations account for 96% of all

shoulder dislocations.

Of the four types of anterior dislocations, subcoracoid disloca

tions occur three times more frequently than all the others (subglen

oid, subclavicular, and thoracic) combined. This chapter deals only

with care of subcoracoid, anterior dislocations. All others should be

treated with the assistance of an orthopedic surgeon.

The shoulder is the most flexible joint in the human body; con

sequently, it is the most unstable and most commonly dislocated

joint. It is designed to enable a wide range of motion of the upper

extremity, in all directions. To accomplish this feat, the actual bony

articulation occupies only a very small part of the overall functional

area of the joint. The glenohumeral joint surface and capsule are

small sliding structures without significant fixed, ligamentous limita

tions. The tendons around the joint, making up the rotator cuff (Fig.

196-1), are the structures primarily responsible for the integrity of

the joint and its complex function.

When the normal joint capsule and rotator cuff restraints are

exceeded, the shoulder moves out of joint. Most frequently the

clinician encounters a dislocation in which the humeral head has

been pulled out of joint and is then held anteriorly and medially by

spasm of the anterior chest wall muscles. This is the subcoracoid,

anterior shoulder dislocation, usually occurring when an abducted,

extended, and externally rotated upper extremity takes a major jolt.

The resulting lever forces the proximal humerus anteriorly out of

the glenoid socket. After the humeral head comes to rest under the

coracoid process, the patient usually presents to the clinician in

extreme pain with a nonfunctional arm. Dislocations may also occur

during a seizure.

The patient will have a loss of the normal shoulder contour, with

a step-off where the deltoid muscle used to be prominent. Instead,

the acromion becomes very prominent. The contour of the humeral

head may be noted in the anterior chest wall region. Clinically, a

hollow can be appreciated beneath the acromion process, due to the

missing humeral head. The arm will frequently be held in a slightly

abducted, externally rotated posture. A neurologic deficit, most fre

quently involving the axillary nerve (provides innervation for shoul

der abduction and sensation over the deltoid), may be noted on

careful examination. Additional neurovascular compromise may be

evident, but it is uncommon with subcoracoid, anterior dislocations.

Radiographs should be obtained; it is important to determine the

presence (24% of anterior dislocations) or absence of a fracture

before attempting to reduce the shoulder. Obtain standard radio

graphs of the shoulder. A single anteroposterior (AP) view of the

shoulder will usually demonstrate the abnormal location of the

humeral head. Another view at roughly 90 degrees will not only

confirm the direction of humeral head movement, but help exclude

a fracture or posterior dislocation. A lateral transcapular or a Ytype view will provide this information; an axillary view (Fig. 196-2)

is preferred by some clinicians but it is often difficult to get the

patient to move his or her arm into the necessary position. Alter

natively, in some obese individuals, a computed tomography (CT)

scan may be necessary to determine the direction of the shoulder

dislocation and the presence of concomitant fractures.

INDICATIONS

A subcoracoid, anterior shoulder dislocation is the indication for

treatment.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

The following findings or conditions should generate an immediate

orthopedic consult:

A shoulder dislocation, other than a subcoracoid, anterior

dislocation

Any fracture dislocation of the shoulder

Dislocations that are more than a few days old (higher risk of

vascular injury, especially in older patients)

Other fractures of the shoulder, neck, ribs, or upper extremity

Prior orthopedic surgery for chronic or recurrent shoulder

dislocations

Shoulder dislocations in children (if ossification centers are not

fused, there is usually an associated Salter-Harris fracture)

A patient with neurovascular compromise (other

than mild axillary nerve sensory defect) due to shoulder dislocation

should undergo immediate reduction. Although it is beyond the

scope of this book, even inferior or posterior shoulder dislocations

should undergo immediate reduction if the distal pulse is compro

mised. Although immediate orthopedic assistance is optimal, it may

not always be possible.

EDITORS NOTE:

EQUIPMENT

AND

SUPPLIES

Stretcher

Washcloth or small towel

Soft restraints such as sheets or blankets

Cloth tape, gauze or elastic bandage, padded wrist restraint or

commercially available device for hanging weights from wrist

Weights (5 to 15lbs) or bucket ( 1 2 to 1 gallon size and adequate

tap water or intravenous [IV] fluid)

Intra-articular anesthetic (10 to 20mL of 50:50 mixture 1% or

2% lidocaine with sterile saline), antiseptic solution (e.g.,

chlorhexidine, povidoneiodine), 10- to 20-mL syringe, 25-gauge,

2 1 2 -inch needle

Procedural sedation forms, consent, equipment (see Chapter 2,

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia) and medications (e.g., anal

gesia, muscle relaxant, narcotics, benzodiazepines, reversal

agents)

Shoulder immobilizer or sling and swath

1343

1344

ORTHOPEDICS

Humeral

head

Rotator cuff

Glenoid cavity

Humerus

Clavicle

Acromion

Rotator cuff

Figure 196-1 Anatomy of the shoulder joint and how the tendons of the

muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor) form

the rotator cuff. Also see Chapter 185, Musculoskeletal Ultrasonography, and

Chapter 192, Joint and Soft Tissue Aspiration and Injection (Arthrocentesis).

PREPROCEDURE PATIENT PREPARATION

Patients should be informed about the indications for shoulder

reduction, as well as any alternatives and possible complications.

They should know what to expect and try to relax as much as pos

sible. If a local anesthetic injection will be used, the patient can be

reassured that this should decrease the discomfort. Informed consent

should be obtained appropriate for the procedure(s) to be performed.

PRECAUTIONS

To be successful, this procedure takes some time and relaxationon

the part of both the patient and the clinician. The procedure is easy,

but trying to rush it may result in an unsuccessful episode. One

exception is the dislocation witnessed by the sports medicine clini

cian; if the dislocation is not associated with high-energy forces,

some clinicians will reduce the shoulder immediately, fieldside,

without radiographs and before the muscular spasm can occur.

TECHNIQUE

There are a number of available techniques, all designed to apply

gentle and persistent tension on the spasmodic chest wall muscles,

to elongate them, and to reestablish the mobility of the humeral

head. Once this is done, the humeral head will usually track or be

gently manipulated back into the glenoid fossa. The patient is prob

ably best served by the simplest technique, the one that minimizes

both operator and patient stress. Typically, this is the Stimson tech

nique, wherein weight loading and time can be used to gently

stretch the muscles and reduce the joint. Certainly, this is the least

Figure 196-2 Radiographs should include a view at 90 degrees from

the anteroposterior view, such as this axillary view. Such a projection helps

document the direction (anterior vs. posterior) of the shoulder dislocation.

traumatic technique for the shoulder and should help minimize

the chances of a fracture developing related to the reduction

process.

Other techniques may also be successful. Although many have

been described in the literature, all of the listed techniques have

been tested and are effective in a situation where the clinician is

willing to take his or her time with the reduction. Experience sug

gests that the clinician should not attempt more than two reduction

procedures. If the second attempt is unsuccessful, the resultant

muscle spasm will likely prevent closed reduction in a safe manner.

Call the orthopedic surgeon if the second attempt is unsuccessful.

Intra-articular Anesthetic

Some experts recommend the injection of intra-articular anesthetic

with every shoulder reduction (see also Chapter 192, Joint and Soft

Tissue Aspiration and Injection [Arthrocentesis]). It can also be

used if procedural sedation is contraindicated.

1. Identify the hollow area where the humeral head used to be

located, 2cm (two fingerbreadths) directly inferior to the lateral

border of the now prominent acromion process. Apply antiseptic

solution to the skin over this area and allow to dry.

2. Using sterile technique, insert the 25-gauge, 2 1 2 -inch needle into

this area, perpendicular to the skin, to a depth of 2cm. Inject 10

to 20mL of a 50:50 mixture of local anesthetic and sterile saline

solution.

Stimson Technique

1. Using this technique, procedural sedation is often unnecessary;

some experts use the injected local intra-articular anesthetic.

Also, there are reports of a 96% success rate, and there is no need

for an assistant. Conversely, the prone position may be impos

sible to use because of other injuries; procedural sedation is also

not recommended because the prone position may interfere with

respiration. Procedural sedation is even relatively contraindi

cated because of the prolonged nature of this technique.

2. The patient is placed in the prone position on a stretcher with

the affected arm hanging over the side. A rolled-up washcloth or

small towel can be placed beneath the coracoid process and

pectoralis major muscle as needed for comfort. The clinician may

want to wrap soft restraints (sheets or blankets) around the bed

and the patient at the hips to prevent him or her from falling off

the stretcher. A weight (usually from 5 to 15lbs) is affixed to the

wrist to provide longitudinal, sustained traction. Wrapping tape,

a gauze or elastic bandage, or a padded wrist restraint around the

wrist should provide secure fixation of the weight to the limb.

Commercial devices are also available for securing and hanging

a weight from the wrist. A bucket of water can be used if weights

are not available; the disadvantage for the patient is having to

hold the bucket for a considerable length of time. IV fluid can

be used to gradually increase the traction as the bucket fills up

(Fig. 196-3).

3. With time (usually 15 to 30 minutes) and relaxation, the shoul

der will usually reduce itself. Occasionally (perhaps after 30

minutes), the clinician will need to facilitate the reduction by

grasping the forearm and gently twisting it, externally first and

then internally, while the arm is still under traction. Either the

patient or clinician may feel a clunk as the joint is reduced,

and there may be brief fasciculations of the deltoid muscle.

However, the reduction may be more subtle; if the patient can

touch his or her nose or the opposite shoulder with the index

finger of the affected upper extremity, it usually indicates a suc

cessful reduction.

4. After the shoulder has been reduced, hold the limb in internal

rotation against the abdomen and adduction (humerus against

the lateral trunk) with a shoulder immobilizer or sling and swath

196 SHOULDER DISLOCATIONS

1345

A

Figure 196-3 Gentle, sustained distal traction can provide an effective

means for closed reduction of an anterior dislocation. As the intravenous

fluid slowly empties into the bucket, the traction force gradually increases.

device. A careful postreduction neurovascular assessment is

required.

5. While keeping the shoulder immobilized, obtain appropriate

postreduction radiographs to determine whether adequate reduc

tion of the joint surfaces has been achieved. A congruousappearing joint without significant distraction (interposed tissue)

between the glenoid and the humerus should be noted. Occa

sionally, comparison shoulder radiographs or a postreduction CT

scan may be required. Some recent studies question the value of

postreduction imaging, but in most communities it is still the

standard of care.

Scapular Manipulation Technique

The patient may or may not require analgesia or injected anesthesia

for this technique because there is somewhat less manipulation

required (and less chance of injury) than with most other tech

niques. Using this technique, the glenoid fossa is repositioned rather

than just the humeral head. Scapular manipulation may be per

formed with the patient prone, sitting, or supine. When the patient

is prone or supine, traction is applied to the arm by an assistant (or

by attached weights if the patient is prone). The shoulder is gently

and gradually flexed by an assistant to a 90-degree position, and from

5 to 15lbs of traction is required. The clinician then uses one hand

to rotate the inferior aspect of the scapula upward and medially, and

the other hand to rotate the superior aspect laterally (Fig. 196-4).

When the patient is sitting, an assistant provides forward traction

on the affected arm with countertraction against the head of the

humerus to obtain the same 90 degrees of flexion. From behind the

patient, the clinician manipulates the scapula as described previ

ously. If reduction does not occur within 1 to 3 minutes, a small

degree of dorsal displacement of the inferior scapular tip may be

helpful. At this point, slight external rotation of the humerus by an

assistant while traction is maintained on the humerus and the

scapula is being manipulated may also be helpful. There have never

been complications reported from using this technique; however, it

is a cumbersome process. Reduction may also be very subtle when

accomplished by this technique, without a perceived clunk. This

technique may be used when other injuries limit repositioning the

patient.

Hennepin Technique

The Hennepin technique is named after the Hennepin County

Emergency Medical Center (Minnesota), where the technique was

B

Figure 196-4 Scapular manipulation technique. A, An assistant flexes

the patients arm (or if the patient is prone, it can be flexed by gravity

and weights, as with the Stimson technique). It must be slowly brought

to a 90-degree position. The clinician then rotates the inferior scapular tip

upward and medially, and the superior aspect laterally (clockwise on the right

shoulder when viewed from back, counterclockwise on the left shoulder).

B, The same technique with the patient in supine position. With the patients

shoulder and elbow both flexed 90 degrees, and the shoulder adducted,

gentle upward pressure is maintained by an assistant while the scapula is

manipulated as described.

first described. It is the technique preferred by some authors for

anterior shoulder dislocations. There is less manipulation than with

most other techniques, a lower probability of neurovascular or mus

culoskeletal damage, and little or no need for analgesia (although

an injection of intra-articular anesthesia may be beneficial). The

patient is seated upright, reclining at 45 degrees, or supine. With

the clinician stabilizing the patients elbow joint of the affected arm

with one hand, the clinicians other hand is used to grasp the

patients wrist. Slowly (it can take up to 10 minutes to accomplish),

the patients forearm is externally rotated until there is 90 degrees

of external rotation (Fig. 196-5). The procedure should be stopped

if the patient experiences pain or discomfort, but do not release the

arm or allow it to return to its original position. Usually, after allow

ing the musculature or spasm to relax, the procedure can be contin

ued without analgesia. If pain or discomfort persists, the patient may

require analgesia. The reduction usually occurs by the time the

forearm has reached 90 degrees of external rotation; if it has not,

the arm is slowly elevated. Occasionally, it will need to be elevated

to the level that the patient can touch his or her contralateral ear

(over the head). If reduction still does not occur, the humeral head

is gently manipulated toward the glenoid until it reduces.

Modified Kocher Maneuver

The modified Kocher maneuver is similar to the Hennepin tech

nique. The patient is placed supine with the arm of the affected

shoulder over the edge of the gurney, and analgesia or injected

anesthesia is provided if necessary. The patients forearm, with the

1346

ORTHOPEDICS

Fulcrum Technique

With the patient supine or sitting, a firmly rolled towel, sheet, or

blanket, 6 to 8 inches in diameter, is placed as a fulcrum within the

axilla of the affected shoulder. The distal humerus is used as a lever

and is adducted gently, with simultaneous posterolateral manipula

tion of the humeral head. This technique increases the forces

applied; therefore, the risk of complications is increased.

Boss-Holzach-Matter Technique

The patient sits against the maximally raised head of a gurney and

wraps his or her forearms around the ipsilateral knee, which is flexed

at 90 degrees. The head of the gurney is then lowered. The patient

is asked to hyperextend the neck while leaning back and shrugging

the shoulders anteriorly. This technique reportedly does not require

analgesia.

Hippocratic Technique

Because the Hippocratic technique is no longer recommended, it is

included only for historical interest. The clinician places his or her

foot against the chest wall to provide countertraction and then

manipulates the arm. This technique can cause serious neurovascu

lar trauma.

C

Figure 196-5 Hennepin and modified Kocher techniques. Both techniques start with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees (A), and then fully externally

rotated (B). For the modified Kocher, the forearm is then returned to complete internal rotation while gentle shoulder joint pressure is applied. The

Hennepin technique (C) is continued from (B), if necessary, with elevation

of the arm and manipulation of the joint posteriorly until the arm is overhead

and the dislocation is reduced.

A

elbow held at 90 degrees, is then rotated externally (abducting

superiorly) over at least a 5-minute period (see Fig. 196-5), with

simultaneous gentle downward pressure applied on the dislocation.

After the arm reaches 120 degrees of rotation, the arm is brought

back to internal rotation, at which time the reduction usually

occurs.

1020

Milch Technique

With the patient sitting or supine, the arm is moved to 10 to 20

degrees of forward flexion with slight abduction. One of the clini

cians hands is then used to gently guide the patients arm (grasping

at the elbow) in this slightly abducted position and using slight

traction, until it is directly overhead (Fig. 196-6). The patient may

be able to move the arm without assistance to this position; however,

there is usually too much pain and spasm. While this is occurring,

the clinicians other hand is placed on the humeral head to prevent

it from moving downward. When the arm is located directly over

head, the rotator cuff muscles are all in alignment, and all crossstresses are eliminated. Using just his or her thumb, the clinician

should be able to direct the humeral head superiorly over the rim of

the glenoid and into the fossa. Otherwise, abduction of the arm and

outward traction at the shoulder are increased and the arm brought

through a full, lateral downward arc. Reduction is usually signified

by an audible or palpable clunk.

C

Figure 196-6 Milch technique. A, The arm is started at 10 to 20 degrees

of flexion and slight abduction. B, Elevation continues slowly, with slight distal

traction, until the arm is directly overhead. The patient may be able to raise

the arm on his or her own. The head of humerus should be held immobile

at this stage of maneuver. C, If no reduction occurs with gentle, direct

manipulation of the head of the humerus, the arm is then slowly brought

through a full, lateral downward arc, maintaining constant outward traction

until reduction occurs. Note that this is the only step of the procedure in

which outward traction is maintained.

196 SHOULDER DISLOCATIONS

COMPLICATIONS

CPT/BILLING CODES

If the shoulder dislocation proves irreducible, an orthopedic surgeon

should be consulted and the use of general anesthesia considered.

Fracture (due to the dislocation or reduction [iatrogenic]) and neurovascular damage are ever-present risks. Up to 50% of anterior

dislocations have a Hill-Sachs deformity, an impaction fracture

defect in the posterolateral portion of the humeral head. A Bankart

lesion may also be noted, which is an avulsed fragment of the

glenoid labrum with contiguous bone. Both lesions tend to get worse

the longer the humeral head remains dislocated.

Many clinicians obtain postreduction radiographs to document

reduction of the joint, any injury associated with the reduction, and

any bony abnormalities such as the aforementioned lesions.

Another risk after a shoulder dislocation is redislocation. In

patients followed for 10 years, age at initial dislocation was the only

predictor of recurrence; duration of subsequent immobilization had

no effect. Rotator cuff tears and hemarthrosis are more common with

inferior dislocation and in patients older than 60 years of age. To

avoid serious complications of procedural sedation, adequate respiratory

support measures and monitoring should be present. Patients need

to be observed after such sedation to ensure they are awake, alert,

and oriented before discharge.

23650

POSTPROCEDURE EDUCATION

AND

CARE

Patients may need oral analgesic medications, possibly even narcot

ics, for a few days. Those younger than 20 years of age should be

immobilized for 3 weeks, patients aged 20 to 40 years should be

immobilized for 1 to 2 weeks, and patients older than 60 years should

have less than 1 week of immobilization. Appropriate clinical, neu

rologic, and radiographic follow-up examinations should be made

throughout this time to confirm maintenance of the reduction. After

the designated period of immobilization, assign a gentle strengthen

ing program, with particular emphasis on the shoulder internal rota

tors. Unrestricted external rotation, abduction, and lifting activities

are usually not permitted for a period of 3 months. Even combing

the hair combines external rotation and abduction and should be

avoided indefinitely on the side of dislocation. With recurrent dis

locations, an arthrogram, CT arthrogram, magnetic resonance

imaging, or arthroscopy might be warranted to help identify an

anatomic variant that might make the patient more prone to redis

location. Patients with peripheral neuropathies, syringomyelia, and

psychiatric histories may be more prone to dislocating their shoul

ders, and these underlying conditions should be considered in

patients with repeated dislocations.

23655

1347

Closed treatment of shoulder dislocation, with manipula

tion, without anesthesia

Closed treatment of shoulder dislocation, with manipula

tion, requiring anesthesia

ICD-9-CM DIAGNOSTIC CODES

718.01

718.11

718.31

831

831.0

831.1

Articular cartilage disorder, shoulder region (old rupture

of ligaments)

Loose body in joint, shoulder region

Recurrent dislocation of joint, shoulder region

Dislocation of shoulder

The following five-digit subclassification is for use with

category 831:

0 Shoulder, unspecified (humerus NOS)

1 Anterior dislocation of humerus

2 Posterior dislocation of humerus

3 Inferior dislocation of humerus

4 Acromioclavicular (joint) (clavicle)

9 Other (scapula)

Closed dislocation

Open dislocation

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The editors wish to recognize the many contributions by Fred M.

Hankin, MD, and J. Mark Wiedemann, MD, MS, to this chapter in

the previous two editions of this text.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Doyle WL, Ragar T: Use of the scapular manipulation method to reduce

an anterior shoulder dislocation in the supine position. Ann Emerg Med

27:9294, 1996.

Eiff MP, Hatch RL, Calmbach WL: Fracture Management for Primary Care,

2nd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2003.

Roberts JR, Hedges JR (eds): Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine,

4th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2004.

Sineff SS, Reichman EF: Shoulder joint dislocation reduction. In Reich

man EF, Simon RR (eds): Emergency Medicine Procedures. New York,

McGraw-Hill, 2004, pp 593613.

Stimson LA: An easy method of reducing dislocations of the shoulder and

hip. Med Rec 57:356357, 1900.

Tuggy M, Garcia J: Procedures Consult. Available at www.procedures

consult.com, and as an application at www.apple.com/iTunes.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Bab IDokument2 SeitenBab IkhalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Menu Ramadhan Umi CateringDokument2 SeitenMenu Ramadhan Umi CateringkhalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parasit Malaria Dan FilariaDokument25 SeitenParasit Malaria Dan FilariaVithiya Chandra SagaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- GGDokument2 SeitenGGkhalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Termination of AED Treatment in Patients in RemissionDokument21 SeitenTermination of AED Treatment in Patients in RemissionkhalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar - PustakaDokument4 SeitenDaftar - Pustakaelfon_gleeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar - PustakaDokument4 SeitenDaftar - Pustakaelfon_gleeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion Sickness yDokument2 SeitenMotion Sickness ykhalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines Pptpresentation 001Dokument43 SeitenGuidelines Pptpresentation 001khalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3) Abstrak dst1Dokument8 Seiten3) Abstrak dst1khalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnosis and Management of Miliary TuberculosisDokument28 SeitenDiagnosis and Management of Miliary TuberculosiskhalidaharwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- SOAP Progress NotesDokument11 SeitenSOAP Progress NotesShan SicatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leoline Installation and MaintenanceDokument8 SeitenLeoline Installation and MaintenanceFloorkitNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPVC Price ListDokument8 SeitenCPVC Price ListYashwanth GowdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- OGJ Worldwide Refining Survey 2010Dokument67 SeitenOGJ Worldwide Refining Survey 2010Zahra GhNoch keine Bewertungen

- hw410 Unit 9 Assignment 1Dokument8 Seitenhw410 Unit 9 Assignment 1api-600248850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Geotechnical Engineering GATE Previous QuestionsDokument35 SeitenGeotechnical Engineering GATE Previous QuestionsSurya ChejerlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leader Ship Assessment: Student No 374212036Dokument4 SeitenLeader Ship Assessment: Student No 374212036Emily KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Competitor Analysis: Square PharmaceuticalsDokument5 SeitenCompetitor Analysis: Square PharmaceuticalsShoaib HussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supplementary Spec To API Specification 17D Subsea Wellhead and Tree Equipment With Justifications S 561Jv2022 11Dokument81 SeitenSupplementary Spec To API Specification 17D Subsea Wellhead and Tree Equipment With Justifications S 561Jv2022 11maximusala83Noch keine Bewertungen

- LabStan - July 16-17, 23-24, 30-31, Aug 6-7Dokument25 SeitenLabStan - July 16-17, 23-24, 30-31, Aug 6-7CandypopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lead in Water: Standard Test Methods ForDokument17 SeitenLead in Water: Standard Test Methods ForAMMARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Aquaponik Jada BahrinDokument36 SeitenJurnal Aquaponik Jada BahrinbrentozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surveys For Maint'Ce ClassDokument7 SeitenSurveys For Maint'Ce ClassSuhe EndraNoch keine Bewertungen

- SurveyDokument1 SeiteSurveyJainne Ann BetchaidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LaserDokument12 SeitenLasercabe79Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3.3 Inside An AtomDokument42 SeitenLesson 3.3 Inside An AtomReign CallosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fitting in and Fighting Back: Stigma Management Strategies Among Homeless KidsDokument24 SeitenFitting in and Fighting Back: Stigma Management Strategies Among Homeless KidsIrisha AnandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cell Division-Mitosis Notes: 2 New CellsDokument21 SeitenCell Division-Mitosis Notes: 2 New CellsCristina MariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dingenen 2017Dokument14 SeitenDingenen 2017pedro.coleffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allowable Stresses of Typical ASME Materials - Stainless SteelDokument5 SeitenAllowable Stresses of Typical ASME Materials - Stainless SteelChanchal K SankaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bars Performance AppraisalDokument6 SeitenBars Performance AppraisalPhillip Miler0% (1)

- Neicchi 270 ManualDokument33 SeitenNeicchi 270 Manualmits2004Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bycatch Reduction Devices - PresentationDokument92 SeitenBycatch Reduction Devices - PresentationSujit Shandilya0% (1)

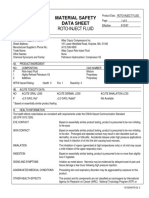

- Material Safety Data Sheet Roto-Inject FluidDokument5 SeitenMaterial Safety Data Sheet Roto-Inject FluidQuintana JoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNIT-5 International Dimensions To Industrial Relations: ObjectivesDokument27 SeitenUNIT-5 International Dimensions To Industrial Relations: ObjectivesManish DwivediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mechanism of Enzyme ActionDokument19 SeitenMechanism of Enzyme ActionRubi AnnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vertical Mills V2 0Dokument56 SeitenVertical Mills V2 0recai100% (1)

- Ableism - What It Is and Why It Matters To EveryoneDokument28 SeitenAbleism - What It Is and Why It Matters To Everyonellemma admasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eastman Methyl N-Amyl Ketone (MAK) and Eastman Methyl Isoamyl Ketone (MIAK)Dokument4 SeitenEastman Methyl N-Amyl Ketone (MAK) and Eastman Methyl Isoamyl Ketone (MIAK)Chemtools Chemtools100% (1)

- 900 ADA - Rev13Dokument306 Seiten900 ADA - Rev13Miguel Ignacio Roman BarreraNoch keine Bewertungen