Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Perpetual War by Matt Hall

Hochgeladen von

djriverside0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

29 Ansichten1 SeiteA short piece describing the problems of Kant's "Perpetual Peace", explaining why his theory may have been flawed from the beginning.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenA short piece describing the problems of Kant's "Perpetual Peace", explaining why his theory may have been flawed from the beginning.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

29 Ansichten1 SeitePerpetual War by Matt Hall

Hochgeladen von

djriversideA short piece describing the problems of Kant's "Perpetual Peace", explaining why his theory may have been flawed from the beginning.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 1

Matthew Hall

Q: Why has perpetual peace proved elusive?

A: Let us first limit war to the use of force by large-scale political units such as states or

empires.1 Kants idea of perpetual peace mentions civil war, for example, but does not claim to

fix or prevent it other than allowing outside republican states to freely intervene. Further, history

has shown that even republican states can devolve into brutal internal conflicts.

Creating a perpetual peace requires understanding of the causes of war, which are many and

diverse, but could be synthesized into at least these four points:

1. Another states power is so great and terrifying that it must be opposed.

2. Another states actions are morally bankrupt, and must be stopped.

3. Another state has broken the rules we have agreed upon as an international

community.

4. Another state has something we want, and we will use force to get it.

Each of these formulations of war loosely associates with a particular theory: realism, liberalism,

constructivism, and the fourth with theory of the human condition as selfish and violent. Kants

prescription for perpetual peace attempted to deal with all four issues: limit passive state power,

create morally good republics, refrain from external interference with affairs, enforce

international norms equally and fairly, and act hospitably and non-greedily to limit selfish

impulses

Kant could not anticipate that each issue would evolve and change. First, standing armies

developed a new companion, nuclear weapons, which make direct, total conflict with a

superpower a dubious proposition. Second, neutrality on the policies of foreign states requires

ignoring genocide and human rights violations. Even ostensible republics have chosen to

commit terrible crimes of violence and oppression outside of civil war. Third, states can choose

to ignore certain international laws or enforce them only when it pleases them. The most

powerful states get away with violations, even under theoretical republican bodies, and protect

even vile allies.

The overall issue with perpetual peace is that the future is free. To attempt to create perpetual

peace, rather than peace in our time, is to attempt to control the decisions of future people.

Technologies, people, and issues will change. The rules which help us now may seem

antiquated to those who come next. To create a perpetual peace requires the use of man as a

means to a future, unchanging end. Even if that were possible, it would violate the Kantian

moral imperative: men should not serve the cause of peace, but rather, peace should serve

mankind. Perhaps, then, perpetual peace has remained elusive because it is not so noble a

goal as it seems. More pragmatically, perpetual peace remains elusive because times and

circumstances change, which requires new approaches to maintain peace.

1 Thomas, Claire. "war." In The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. : Oxford University Press, 2009.

http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezpprod1.hul.harvard.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199207800.001.0001/acref-9780199207800-e-1450.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Horizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationDokument12 SeitenHorizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationNick Wallis100% (1)

- Dahl - On DemocracyDokument23 SeitenDahl - On DemocracyFelix de Jongh90% (50)

- Haebus Corpus WritDokument4 SeitenHaebus Corpus WritHarshita Sharma100% (1)

- Martinez Vs Grano - G.R. No. 16709. August 8, 1921Dokument8 SeitenMartinez Vs Grano - G.R. No. 16709. August 8, 1921Ebbe DyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integralismo e SociedadeDokument153 SeitenIntegralismo e SociedadeAndre SetteNoch keine Bewertungen

- DUE PROCESS To JURIS OF SB Crimpro CapellanDokument53 SeitenDUE PROCESS To JURIS OF SB Crimpro Capellanpepper6449Noch keine Bewertungen

- PhilawsophiaDokument4 SeitenPhilawsophiasan71% (7)

- G.R. No. 76714, June 2, 1994: Vda de Perez Vs ToleteDokument5 SeitenG.R. No. 76714, June 2, 1994: Vda de Perez Vs ToleteGLORILYN MONTEJONoch keine Bewertungen

- Lim Siengco v. Lo SengDokument2 SeitenLim Siengco v. Lo SengIldefonso HernaezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francisco Depra Vs Agustin DumlaoDokument1 SeiteFrancisco Depra Vs Agustin DumlaoPaulino Belga IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- (Studies in Childhood and Youth) Manfred Liebel, Karl Hanson, Iven Saadi, Wouter Vandenhole (Auth.) - Children's Rights From Below - Cross-Cultural Perspectives-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2012) PDFDokument276 Seiten(Studies in Childhood and Youth) Manfred Liebel, Karl Hanson, Iven Saadi, Wouter Vandenhole (Auth.) - Children's Rights From Below - Cross-Cultural Perspectives-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2012) PDFJahanJamiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schoenberg's Kristalnacht FugueDokument32 SeitenSchoenberg's Kristalnacht FugueThmuseoNoch keine Bewertungen

- RecitDokument115 SeitenRecitkitakatttNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Medicine Tranx (Family Life Cycle)Dokument4 SeitenCommunity Medicine Tranx (Family Life Cycle)Kaye NeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011 Hric Sco Whitepaper Full PDFDokument372 Seiten2011 Hric Sco Whitepaper Full PDFZarak Khan (zarakk47)Noch keine Bewertungen

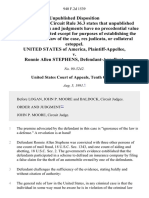

- United States v. Ronnie Allen Stephens, 940 F.2d 1539, 10th Cir. (1991)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Ronnie Allen Stephens, 940 F.2d 1539, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tribunal Report NandigramDokument97 SeitenTribunal Report Nandigramsupriyo9277100% (1)

- Vi Sem-Ba Pol Sc-Core Course-Modern Political ThoughtDokument66 SeitenVi Sem-Ba Pol Sc-Core Course-Modern Political Thoughtvishal rajputNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labour Law Upcoming Changes October 26 2016 1Dokument84 SeitenLabour Law Upcoming Changes October 26 2016 1zeeshan ansariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wonderland Nurserygoods v. Baby TrendDokument6 SeitenWonderland Nurserygoods v. Baby TrendPatent LitigationNoch keine Bewertungen

- UnpublishedDokument5 SeitenUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- IPC LL.B. Assignment ProformaDokument12 SeitenIPC LL.B. Assignment ProformasanolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973)Dokument34 SeitenDoe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grounds To Dispossess A Lessee and Suppletory EffectDokument29 SeitenGrounds To Dispossess A Lessee and Suppletory EffectMDR Andrea Ivy DyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computer Associates International v. AltaiDokument2 SeitenComputer Associates International v. Altaiaspiringlawyer1234Noch keine Bewertungen

- 83 Order Finding Eric C. Blue in Contempt of Court and Requiring Turnover of Financial Records PDFDokument4 Seiten83 Order Finding Eric C. Blue in Contempt of Court and Requiring Turnover of Financial Records PDFEric GreenNoch keine Bewertungen

- A.M. No. 99-10-05-0 Procedure in Extra-Judicial Foreclosure of MortgageDokument2 SeitenA.M. No. 99-10-05-0 Procedure in Extra-Judicial Foreclosure of Mortgagechill21ggNoch keine Bewertungen

- 37 People v. GalapinDokument1 Seite37 People v. Galapin刘王钟Noch keine Bewertungen

- Labor CaseDokument104 SeitenLabor CaseTricia GrafiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest Prov RemDokument6 SeitenDigest Prov RemDiosa Mae SarillosaNoch keine Bewertungen