Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Bagajo V Marave

Hochgeladen von

Sonia Mae C. Balbaboco0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

191 Ansichten1 Seitedigest

Originaltitel

Bagajo v Marave

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldendigest

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

191 Ansichten1 SeiteBagajo V Marave

Hochgeladen von

Sonia Mae C. Balbabocodigest

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 1

MARCELA M. BAGAJO v.

JUDGE MARAVE AND

PEOPLE

(full text)

Bagajo, a teacher, left her classroom to go to the

principal's office. While the teacher was thus out of the

room, complainant Wilma Alcantara, one of her pupils,

left her desk and went to chat with Lilibeth Purlas, a

classmate, while leaning over the desk of Ponciano

Navarro, another classmate. At that juncture, a fourth

classmate, Benedicta Guirigay passed near Wilma, who

suddenly raised her leg causing the former to stumble

on it and fall down, her head hitting the edge of the

desk, her stomach a sharp pointed umbrella and her

knee a nail of the desk. She fainted. At that precise

moment, petitioner was entering the room. She asked

Wilma what happened but the latter denied having

anything to do with what had just taken place.

Petitioner thereupon became angry and, with a piece of

"bamboo stick" which she was using as a pointer

whipped Wilma behind her legs and her thigh, thereby

causing the following injuries, according to the medical

certificate presented in evidence:

1. Linear bruises at the middle half of the dorsal

surface of both legs. it is about four inches in length

and 1/4 centimeter in width. There are three on the

right leg and two on the left leg.

2. Two linear bruises of the same width and length as

above at the lower third of the dorsal surface of the

right thigh.

The above lessions, if without complication, may heal

in four to six days. (Pages 26-27, Record.)

Upon the foregoing facts, petitioner claims in her

appeal that respondent Judge erred in convicting her of

the crime of slight physical injuries. She maintains that

as the teacher, she was just trying to discipline her

pupil Wilma for tripping her classmate and for denying

that she did so. She contends she was not actuated by

any criminal intent. And she is joined in this pose by

the Solicitor General, who recommends her acquittal,

coupled with the observation that although "petitioner

is not criminally liable for her conduct, she may still be

held accountable for her conduct administratively.

In the school premises and during school activities and

affairs, the teacher exercises substitute parental

authority over the students. (Article 349, Civil Code.)

More specifically, according to Article 352, "The

relations between teacher and pupil, professor and

student, are fixed by government regulations and

those of each school or institution. In no case shall

corporal punishment be countenanced. The teacher or

professor shall cultivate the best potentialities of the

heart and mind of the pupil or student." And pursuant

to this provision, Section 150 of the Bureau of Public

Schools Service Manual enjoins:

The use of corporal punishment by teachers (slapping,

jerking, or pushing pupils about), imposing manual

work or degrading tasks as penalty, meting out cruel

and unusual punishments of any nature, reducing

scholarship rating for bad conduct, holding up a pupil

to unnecessary ridicule, the use of epithets and

expressions tending to destroy the pupil's self-respect,

and the permanent confiscation of personal effects of

pupils are forbidden.

In other words, under the foregoing Civil Code and

administrative injunctions, no teacher may impose

corporal punishment upon any student in any case. But

We are not concerned in this appeal with the possible

administrative liability of petitioner. Neither are we

called upon here to pass on her civil liability other than

what could be ex-delicto, arising from her conviction, if

that should be the outcome hereof. The sole question

for Our resolution in this appeal relates exclusively to

her criminal responsibility for the alleged crime of

slight physical injuries as defined in Article 266,

paragraph 2, of the Revised Penal Code, pursuant to

which she was prosecuted and convicted in the courts

below.

In this respect, it is Our considered opinion, and so We

Hold that as a matter of law, petitioner did not incur

any criminal liability for her act of whipping her pupil,

Wilma, with the bamboo-stick-pointer, in the

circumstances proven in the record. Independently of

any civil or administrative responsibility for such act

she might be found to have incurred by the proper

authorities, We are persuaded that she did not do what

she had done with criminal intent. That she meant to

punish Wilma and somehow make her feel such

punishment may be true, but We are convinced that

the means she actually used was moderate and that

she was not motivated by ill-will, hatred or any

malevolent intent. The nature of the injuries actually

suffered by Wilma, a few linear bruises (at most 4

inches long and cm. wide) and the fact that

petitioner whipped her only behind the legs and thigh,

show, to Our mind, that indeed she intended merely to

discipline her. And it cannot be said, that Wilma did not

deserve to be discipline. In other words, it was farthest

from the thought of petitioner to commit any criminal

offense. Actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea.

Nothing said above is intended to mean that this Court

sanctions generally the use of corporal punishment by

teachers on their pupils. All that We hold here is that in

the peculiar circumstances of the instant case before

Us, there is no indication beyond reasonable doubt, in

the evidence before the trial court, that petitioner was

actuated by a criminal design to inflict the injuries

suffered by complainant as a result of her being

whipped by petitioner. What appears is that petitioner

acted as she did in the belief as a teacher exercising

authority over her pupil in loco parentis, she was within

her rights to punish her moderately for purposes of

discipline. Whether or not she exceeded the degree of

moderation permitted by the laws and rules governing

the performance of her functions is not for Us, at this

moment and in this case, to determine.

Absent any applicable precedent indicative of the

concept of the disciplinary measures that may be

employed by teachers under Section 150 of the Bureau

of Public Schools Service Manual quoted above, We feel

it is wiser to leave such determination first to the

administrative authorities.

After several deliberations, the Court has remained

divided, such that the necessary eight (8) votes

necessary for conviction has not been obtained.

Accordingly, the petitioner -accused is entitled to

acquittal.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Juris TeacherDokument14 SeitenJuris TeacherJean NatividadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bagajo Vs MavareDokument3 SeitenBagajo Vs MavareCris 'ingay'Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bagajo Vs MaraveDokument23 SeitenBagajo Vs Maraveroberto valenzuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bagajo v. Marave PDFDokument27 SeitenBagajo v. Marave PDFBob OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bagajo Vs MavareDokument3 SeitenBagajo Vs MavareZonix LomboyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Supreme Court acquits teacher of inflicting corporal punishment on studentDokument14 SeitenPhilippine Supreme Court acquits teacher of inflicting corporal punishment on studentNelson Geverola Balneg100% (1)

- Teacher Whipping Student Not CriminalDokument1 SeiteTeacher Whipping Student Not CriminalJoseph John Santos Ronquillo100% (1)

- Teachers denied power to inflict corporal punishmentDokument9 SeitenTeachers denied power to inflict corporal punishmentaudreyracela100% (1)

- Corporal PunishmentDokument1 SeiteCorporal PunishmentJoyce AmaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gravity of Injuries As A Distinguishing Line Between Corporal Punishment and Child AbuseDokument3 SeitenGravity of Injuries As A Distinguishing Line Between Corporal Punishment and Child AbuseSteve UyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexual Harassment Case Against TeacherDokument3 SeitenSexual Harassment Case Against TeacherJani MisterioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence For Schools and TeachersDokument8 SeitenJurisprudence For Schools and TeachersCharliemagne TilosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti BullyingDokument3 SeitenAnti BullyingGabriel Baldomero IINoch keine Bewertungen

- On Cheating in Examinations: A Letter T O A H I G H School PrincipalDokument5 SeitenOn Cheating in Examinations: A Letter T O A H I G H School PrincipalWynzyl Albien ElojaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts Problem Solving EssayDokument6 SeitenTorts Problem Solving EssayAshika LataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adamson University Faculty and Employees Union. v. Adamson UniversityDokument2 SeitenAdamson University Faculty and Employees Union. v. Adamson UniversityMark Anthony ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- UE v. Jader (G.R. No. 132344 February 17, 2000)Dokument9 SeitenUE v. Jader (G.R. No. 132344 February 17, 2000)Hershey Delos SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 177 Angeles Vs Sison DigestDokument2 Seiten177 Angeles Vs Sison DigestJulius Geoffrey TangonanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Bases of Education: Presented By: Psupt Salvador E Dagoon, Jr. Dcdo/ C, Cib, IcpoDokument104 SeitenLegal Bases of Education: Presented By: Psupt Salvador E Dagoon, Jr. Dcdo/ C, Cib, IcpoSalvador Dagoon Jr100% (3)

- ADAMSON UNIVERSITY FACULTY AND EMPLOYEES UNION, Represented by Its President, and ORESTES DELOS REYES vs. ADAMSON UNIVERSITY (G.R. No. 227070. March 9, 2020)Dokument10 SeitenADAMSON UNIVERSITY FACULTY AND EMPLOYEES UNION, Represented by Its President, and ORESTES DELOS REYES vs. ADAMSON UNIVERSITY (G.R. No. 227070. March 9, 2020)Marianne Hope VillasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teachers' dismissal disputeDokument23 SeitenTeachers' dismissal disputeAnonymous yisZNKXNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amadora V CA Case DigestDokument3 SeitenAmadora V CA Case DigestLatjing SolimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is Loco Parentis Applicable in The Case Faced by Adamson UniversityDokument2 SeitenIs Loco Parentis Applicable in The Case Faced by Adamson UniversityAntonio Jason FabeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Landmark CaseDokument5 SeitenLandmark CaseCheryl Dao-anis AblasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin CaseDokument11 SeitenAdmin CaseDhang Nario De TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Related CasesDokument20 SeitenTeacher Related Casesyamaleihs100% (1)

- Amadora v. CADokument3 SeitenAmadora v. CAkatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angeles VDokument7 SeitenAngeles VIbiang DeleozNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anonymous Complaint Against Atty. Co UntianDokument3 SeitenAnonymous Complaint Against Atty. Co UntianLeslie Joy MingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti Bullying LawDokument8 SeitenAnti Bullying LawDolores PulisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Was Dismissed Due To The Act of Fondling One of His StudentsDokument2 SeitenTeacher Was Dismissed Due To The Act of Fondling One of His StudentsMichael A. SuzonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper 1Dokument13 SeitenResearch Paper 1Son Gabriel UyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER TENassDokument68 SeitenCHAPTER TENassluvlygaljenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Issues in Education ReportDokument1 SeiteLegal Issues in Education ReportAngelene Mae MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salient Points of Bullying Masteral Needs To Be PrintDokument3 SeitenSalient Points of Bullying Masteral Needs To Be PrintFrances Joan NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law of Delict AssignmentDokument9 SeitenLaw of Delict AssignmentvinnieverilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Analysis SolutionDokument4 SeitenCase Analysis SolutionCristinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doctrine of in Loco ParentisDokument3 SeitenDoctrine of in Loco ParentismesinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standard 5Dokument7 SeitenStandard 5api-519674753Noch keine Bewertungen

- Amadora V CADokument3 SeitenAmadora V CAEmir MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anonymous Complaint Against Atty UntianDokument3 SeitenAnonymous Complaint Against Atty UntianTinersNoch keine Bewertungen

- PARENTAL AND QUASIDokument5 SeitenPARENTAL AND QUASIdevidayal078Noch keine Bewertungen

- 118730-2000-University of The East v. JaderDokument9 Seiten118730-2000-University of The East v. JadermalupitnasikretoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law Case Study AnalysisDokument3 SeitenLaw Case Study Analysisapi-323713948Noch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation RA 10627Dokument19 SeitenPresentation RA 10627Francis A. DacutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Assaulted by StudentDokument3 SeitenTeacher Assaulted by StudentJP De La PeñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angeles vs. Sison jurisdiction student misconductDokument2 SeitenAngeles vs. Sison jurisdiction student misconductAriel Lunzaga50% (2)

- 2016-04-22 Grievance Letter With ExhibitsDokument29 Seiten2016-04-22 Grievance Letter With ExhibitsKathrynRubino100% (1)

- Legal Research CarpenterDokument7 SeitenLegal Research CarpenterlexscribisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liabilities of Public School Teachers and Administrators: (... and How To Avoid Them)Dokument33 SeitenLiabilities of Public School Teachers and Administrators: (... and How To Avoid Them)Van Errl Nicolai SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexual Harassment in The PhilippineDokument7 SeitenSexual Harassment in The Philippinebryan110623Noch keine Bewertungen

- FELINA ROSALDES Vs People of The PhilippinesDokument3 SeitenFELINA ROSALDES Vs People of The PhilippinesHaze Q.Noch keine Bewertungen

- ELC501 Sample of An Argument and The Written Analysis For StudentsDokument7 SeitenELC501 Sample of An Argument and The Written Analysis For Studentsaizuddin93100% (3)

- Children's RightDokument16 SeitenChildren's RightKimber Lee100% (1)

- RA 10627: The Anti-Bullying Act: A PrimerDokument4 SeitenRA 10627: The Anti-Bullying Act: A Primerlynx29Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cathedral School vs. NLRC ruling on serious misconductDokument3 SeitenCathedral School vs. NLRC ruling on serious misconductMarve CabigaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Tort LiabilityDokument8 SeitenTeacher Tort LiabilityDestiny ObscureNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Educational Black Hole (and the Egg Heads that control it)Von EverandThe Educational Black Hole (and the Egg Heads that control it)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Us Vs ValeroDokument1 SeiteUs Vs ValeroSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC denies reopening Aquino murder case based on forensic reportDokument2 SeitenSC denies reopening Aquino murder case based on forensic reportSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V BisdaDokument1 SeitePeople V BisdaSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cabrera Vs TianoDokument2 SeitenCabrera Vs TianoSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMLC vs Glasgow and Citystate Savings BankDokument2 SeitenAMLC vs Glasgow and Citystate Savings BankSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kummer V PeopleDokument2 SeitenKummer V PeopleSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC denies reopening Aquino murder case based on forensic reportDokument2 SeitenSC denies reopening Aquino murder case based on forensic reportSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sicat Vs Ariola, Jr.Dokument2 SeitenSicat Vs Ariola, Jr.Sonia Mae C. Balbaboco100% (1)

- CALIMUTAN V PEOPLEDokument1 SeiteCALIMUTAN V PEOPLESonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chua V CADokument1 SeiteChua V CASonia Mae C. Balbaboco0% (2)

- People Vs EstacioDokument1 SeitePeople Vs EstacioSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evangelista Vs Alto SuretyDokument2 SeitenEvangelista Vs Alto SuretySonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saliling DigestDokument2 SeitenSaliling DigestSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SALA Vs CADokument3 SeitenSALA Vs CASonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chua V CADokument1 SeiteChua V CASonia Mae C. Balbaboco0% (2)

- People Vs Tabarnero Case DigestDokument2 SeitenPeople Vs Tabarnero Case DigestSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Valentin Vs SusiDokument2 SeitenValentin Vs SusiSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delay in Constructing Niche Leads to Moral DamagesDokument1 SeiteDelay in Constructing Niche Leads to Moral DamagesSonia Mae C. BalbabocoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arpon DigestDokument3 SeitenArpon DigestSonia Mae C. Balbaboco100% (1)

- Sibal Vs Valdez DigestDokument1 SeiteSibal Vs Valdez DigestSonia Mae C. Balbaboco0% (1)

- Fernando V AcunaDokument2 SeitenFernando V AcunaSonia Mae C. Balbaboco100% (2)

- mẫu hợp đồng dịch vụ bằng tiếng anhDokument5 Seitenmẫu hợp đồng dịch vụ bằng tiếng anhJade Truong100% (1)

- Appeal of Mrs. QuirosDokument3 SeitenAppeal of Mrs. QuirosPatrio Jr SeñeresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Let's - Go - 4 - Final 2.0Dokument4 SeitenLet's - Go - 4 - Final 2.0mophasmas00Noch keine Bewertungen

- 06 - Chapter 1 - 2Dokument57 Seiten06 - Chapter 1 - 2RaviLahaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Checklists - Bridge Procedures Guide International Chamber of ShippingDokument6 SeitenChecklists - Bridge Procedures Guide International Chamber of ShippingPyS JhonathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romantic Book CollectionDokument5 SeitenRomantic Book CollectionNur Rahmah WahyuddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- BTH Community Guide FinalDokument12 SeitenBTH Community Guide FinalNgaire TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gulf WarDokument3 SeitenThe Gulf WarShiino FillionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Major Political Ideologies in 40 CharactersDokument3 SeitenMajor Political Ideologies in 40 CharactersMarry DanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 MWSS Vs ACT THEATER INC.Dokument2 Seiten7 MWSS Vs ACT THEATER INC.Chrystelle ManadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thers Something About Mary ScriptDokument142 SeitenThers Something About Mary ScriptsporangiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epstein DocsDokument2.024 SeitenEpstein DocsghfghfNoch keine Bewertungen

- 102 - Aboitiz Shipping Corporation v. Insurance Company of North AmericaDokument8 Seiten102 - Aboitiz Shipping Corporation v. Insurance Company of North AmericaPatrice ThiamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ra 9829Dokument21 SeitenRa 9829JayMichaelAquinoMarquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- AhalyaDokument10 SeitenAhalyanieotyagiNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Jose Elementary School Grade IV Learners List 2022-2023Dokument22 SeitenSan Jose Elementary School Grade IV Learners List 2022-2023fe purificacionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suspects Apprehended After Vaal River Murder - OFMDokument1 SeiteSuspects Apprehended After Vaal River Murder - OFMAmoriHeydenrychNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challan Office Copy Challan Candidate'SDokument1 SeiteChallan Office Copy Challan Candidate'SVenkatesan SwamyNoch keine Bewertungen

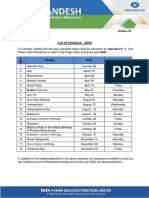

- Holiday List - 2020Dokument3 SeitenHoliday List - 2020nitin369Noch keine Bewertungen

- M45 QuadmountDokument6 SeitenM45 Quadmountalanbrooke1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Protocol Guide For Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts January 2013Dokument101 SeitenProtocol Guide For Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts January 2013Nok Latana Siharaj100% (1)

- Islam Teaches Important LessonsDokument141 SeitenIslam Teaches Important LessonsAnonymous SwA03GdnNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Geography of The Provincial Administration of The Byzantine Empire (Ca. 600-1200) (Efi Ragia)Dokument32 SeitenThe Geography of The Provincial Administration of The Byzantine Empire (Ca. 600-1200) (Efi Ragia)Agis Tournas100% (1)

- 07-22-2016 ECF 612 USA V RYAN PAYNE - OBJECTION To 291, 589 Report and Recommendation by Ryan W. PayneDokument14 Seiten07-22-2016 ECF 612 USA V RYAN PAYNE - OBJECTION To 291, 589 Report and Recommendation by Ryan W. PayneJack RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of An Arbitration AgreementDokument28 SeitenEffect of An Arbitration AgreementUpendra UpadhyayulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 - DNVs Hull STR For WW - Naming of StructureDokument27 Seiten02 - DNVs Hull STR For WW - Naming of StructureArpit GoyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demat Account Closure Form PDFDokument1 SeiteDemat Account Closure Form PDFRahul JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACT NO. 496 "The Land Registration Act. "Dokument1 SeiteACT NO. 496 "The Land Registration Act. "Emil Bautista100% (3)

- Password Reset B2+ CST 4BDokument1 SeitePassword Reset B2+ CST 4BSebastian GrabskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Should MustDokument2 SeitenShould MustSpotloudNoch keine Bewertungen