Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Consti 2 Outline (Bill of Rights Sec 1-4)

Hochgeladen von

Anasor GoOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Consti 2 Outline (Bill of Rights Sec 1-4)

Hochgeladen von

Anasor GoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

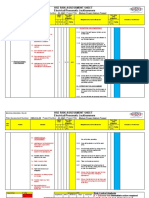

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

III. Bill of Rights

A. Definition/scope

1.

2.

Civil rights - Those rights that belong to every

citizen of the state or country, or, in a wider sense,

to all its inhabitants, and are not connected with

the organization or administration of government.

They include the rights to property, marriage, equal

protection of the laws, freedom of contract, etc.. They are

rights appertaining to a person by virtue of his citizenship

in a state or community. Such term may also refer, in its

general sense, to rights capable of being enforced or

redressed in a civil action.

Political rights - They refer to the right to

participate,

directly

or

indirectly,

in

the

establishment or administration of government,

e.g., the right of suffrage, the right to hold public office,

the right to petition and, in general the rights appurtenant

to citizenship vis-a-vis the management of government

Simon vs. Commission on Human Rights,

G.R. No. 100150, January 5, 1994

Doctrine: Civil rights are those rights that belong to

every citizen of the state or country, or, in a wider

sense, to all its inhabitants, and are not connected with

the organization or administration of government;

political rights refer to the right to participate, directly

or indirectly, in the establishment or administration of

government.

FACTS: On July 23, 1990, the Commission on Human Rights

(CHR) issued and order, directing the petitioners "to desist from

demolishing the stalls and shanties at North EDSA pending the

resolution of the vendors/squatters complaint before the

Commission" and ordering said petitioners to appear before the

CHR.

On September 10, 1990, petitioner filed a motion to

dismiss questioning CHR's jurisdiction and supplemental

motion to dismiss was filed on September 18, 1990 stating that

Commissioners' authority should be understood as being

confined only to the investigation of violations of civil and

political rights, and that "the rights allegedly violated in this

case were not civil and political rights, but their privilege to

engage in business".

On March 1, 1991, the CHR issued and Order denying

petitioners' motion and supplemental motion to dismiss. And

petitioners' motion for reconsideration was denied also in an

Order, dated April 25, 1991.

The Petitioner filed a petition for prohibition, praying for a

restraining order and preliminary injunction. Petitioner also

prayed to prohibit CHR from further hearing and investigating

CHR Case No. 90-1580, entitled "Ferno, et.al vs. Quimpo, et.al".

ISSUE: W/N the issuance of an "order to desist" is within the

extent of the authority and power of the CRH.

HELD: No, the issuance of an "order to desist" is not within

the extent of authority and power of the CHR. Article XIII,

Section 18(1), provides the power and functions of the CHR to

"investigate, on its own or on complaint by any part, all forms

of human rights violation, involving civil and political rights".

The "order to desist" however is not investigatory in

character but an adjudicative power that it does not possess.

The Constitutional provision directing the CHR to provide for

preventive measures and legal aid services to the

underprivileged whose human rights have been violated or

need protection may not be construed to confer jurisdiction on

the Commission to issue an restraining order or writ of

injunction, for it were the intention, the Constitution would

have expressly said so. Not being a court of justice, the CHR

itself has no jurisdiction to issue the writ, for a writ of

preliminary injunction may only be issued by the Judge in any

court in which the action is pending or by a Justice of the CA or

of the SC.

The writ prayed for the petition is granted. The CHR is

hereby prohibited from further proceeding with CHR Case No.

90-1580.

B. Due process of law

A law which hears before it condemns, which

proceeds upon inquiry and renders judgment only after

trial [Darmouth College v. Woodward, 4 Wheaton 518],

Responsiveness to the supremacy of reason,

obedience to the dictates of justice [Ermita-Malate Hotel

& Motel Operators Association v. City of Manila, 20 SCRA 849].

The embodiment of the sporting idea of fair play

[Frankfurter, Mr. Justice Holmes and the Supreme Court, pp 3233 ].

1.

Who are protected

Smith, Bell & Company (Ltd.) vs. Joaquin Natividad,

Collector of Customs of the port of Cebu, 40 Phil 163

Doctrine: Universal in application to all persons, without

regards to any difference in race, color or nationality.

Artificial persons are covered by the protection but only

insofar as their property is concerned.

Facts: This is a petition for a writ of mandamus filed by the

petitioner to compel Natividad to issue a certificate of

Philippine registry in favor of the former for its motor vessel

Bato of more than fifteen tons gross, built in the Philippine

Islands in 1916.

Smith, Bell & Co., (Ltd.), is a corporation organized and

existing under the laws of the Philippine Islands whose majority

stockholders are British subjects. The Bato was brought to Cebu

in the present year for the purpose of transporting plaintiff's

merchandise between ports in the Islands. Application was

made at Cebu, the home port of the vessel, to the Collector of

Customs for a certificate of Philippine registry. The Collector

refused to issue the certificate on the grounds that all the

stockholders of Smith, Bell & Co., Ltd. were not citizens either

of the United States or of the Philippine Islands. The instant

action is the result.

Counsel argues that Act No. 2761 denies to Smith, Bell &

Co., Ltd., the equal protection of the laws because it, in effect,

prohibits the corporation from owning vessels, and because

classification of corporations based on the citizenship of one or

more of their stockholders is capricious, and that Act No. 2761

deprives the corporation of its property without due process of

law because by the passage of the law company was

automatically deprived of every beneficial attribute of

ownership in the Bato and left with the naked title to a boat it

could not use .

Issue: W/N the Government of the Philippine Islands, through

its Legislature, can deny the registry of vessel in its coastwise

trade to corporations having alien stockholders

HELD: YES. Act No. 2761 provides:

Investigation into character of vessel. No application for a

certificate of Philippine register shall be approved until the

collector of customs is satisfied from an inspection of the vessel

that it is engaged or destined to be engaged in legitimate trade

and that it is of domestic ownership as such ownership is

defined in section eleven hundred and seventy-two of this

Code.

Certificate of Philippine register. Upon registration of a

vessel of domestic ownership, and of more than fifteen tons

gross, a certificate of Philippine register shall be issued for it. If

the vessel is of domestic ownership and of fifteen tons gross or

less, the taking of the certificate of Philippine register shall be

optional with the owner.

While Smith, Bell & Co. Ltd., a corporation having alien

stockholders, is entitled to the protection afforded by the dueprocess of law and equal protection of the laws clause of the

Philippine Bill of Rights, nevertheless, Act No. 2761 of the

Philippine Legislature, in denying to corporations such as

Smith, Bell &. Co. Ltd., the right to register vessels in the

Philippines coastwise trade, does not belong to that vicious

species of class legislation which must always be condemned,

but does fall within authorized exceptions, notably, within the

purview of the police power, and so does not offend against the

constitutional provision.

Villegas vs. Hiu Chiong, 86 SCRA 275

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 1

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

Doctrine: The guarantee extends to aliens and includes

the means of livelihood

FACTS: This case involves an ordinance prohibiting aliens

from being employed or engage or participate in any

position or occupation or business enumerated therein,

whether permanent, temporary or casual, without first securing

an employment permit from the Mayor of Manila and paying

the permit fee of P50.00. Private respondent Hiu Chiong Tsai

Pao Ho who was employed in Manila, filed a petition to stop the

enforcement of such ordinance as well as to declare the same

null and void. Trial court rendered judgment in favor of the

petitioner, hence this case.

ISSUE: W/N said Ordinance violates due process of law and

equal protection rule of the Constitution.

HELD: Yes. The ordinance in question violates the due process

of law and equal protection rule of the Constitution. Requiring a

person before he can be employed to get a permit from the

City Mayor who may withhold or refuse it at his will is

tantamount to denying him the basic right of the people in the

Philippines to engage in a means of livelihood. While it is true

that the Philippines as a State is not obliged to admit aliens

within its territory, once an alien is admitted, he cannot be

deprived of life without due process of law. This guarantee

includes the means of livelihood. The shelter of protection

under the due process and equal protection clause is given to

all persons, both aliens and citizens.

2.

Meaning of life, liberty or property

Life includes the right of an individual to his body in its

completeness, free from dismemberment, and extends to the

use of God-given faculties which make life enjoyable [Justice

Malcolm, Philippine Constitutional Law, pp. 320321]. See: Buck

v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200.

Liberty includes the right to exist and the right to be free

from arbitrary personal restraint or servitude, x x x (It) includes

the right of the citizen to be free to use his faculties in all lawful

ways x x x [Rubi v. Provincial Board of Mindoro, 39 Phil 660]

Property is anything that can come under the right of

ownership and be the subject of contract. It represents more

than the things a person owns; it includes the right to secure,

use and dispose of them [Torraco v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197].

i)

Philippine Blooming Mills Employees Organization

(PBMEO) vs. Philippine Blooming Mills Co., 50 SCRA 189

Doctrine: The Bill of Rights is designed to preserve the

ideals of liberty, equality and security against the

assaults of opportunism, the expediency of the passing

hour, the erosion of small encroachments, and the scorn

and derision of those who have no patience with

general principles

FACTS: Petitioners herein alleged that they informed the

respondent Philippine Blooming Mills of their decision to have a

mass demonstration at Malacaang, in protest against alleged

abuses of the Pasig police. The company respondent pleaded to

exclude the employees in the first shift to join the mass

demonstration; however the petitioners still included them. As

a result, the company respondent filed a case thru the city

prosecutor and charged the demonstrating employees of

violation of the CBA. Trial court rendered judgment in favor of

the respondent company, and the petitioners failed to file a

timely motion for reconsideration.

ISSUE: WON the case dismissal as a consequence of a

procedural fault violates due process.

HELD: Yes. The decision of the CIR to dismiss the petition

based on technicality (being 2 days late) was rendered null and

void. (The constitutional rights have dominance over

procedural rules.) And, the company was directed to

reinstate the eight officers with full backpay from date of

separation minus the one day's pay and whatever earnings

they might have realized from other sources during their

separation from service. (The removal from employment of

the officers were deemed too harsh a punishment for

their actions)

Nunez vs. Averia, 57 SCRA 726

Doctrine: Public office is not property; but one

unlawfully ousted from it may institute an action to

recover the same, flowing from the de jure officers

right to office. It is nevertheless a protected right.

Facts: Petitioner CONSTANTINO A. NUEZ, is the protestant in

Election Case No. TM-470 of respondent court contesting the

November 8, 1971 election results in certain precincts for the

mayoralty of Tarnate, Cavite on the ground of fraud,

irregularities and corrupt practices. Original protestee was the

proclaimed mayor-elect Edgardo Morales, who was ambushed

and killed on February 15, 1974 in a barrio of Tarnate and

hence was succeeded by then vice-mayor Rodolfo de Leon

(respondent) who as the incumbent mayor is now substituted in

this action as party respondent. Respondent court had in its

questioned order of January 31, 1974 granted protestee's

motion for dismissal of the election protest on the ground "that

this court has lost its jurisdiction to decide this case for the

reason that the same has become moot and academic," citing

the President's authority under General Order No. 3 and Article

XVII, section 9 of the 1973 Constitution to remove from office

all incumbent government officials and employees, whether

elective or appointive. Upon receipt of respondent's comment

the Court resolved to consider petitioner's petition for review

on certiorari as a special civil action and the case submitted for

decision for prompt disposition thereof.

Issue: W/N public office is a property right protected by the

Constitution.

Held: No, public office is not considered a property; but to the

extent that security of tenure cannot be compromised without

due process, it is in a limited sense analogous to property.

ACCORDINGLY, respondent court's dismissal order of January

31, 1974 is hereby set aside and respondent court is directed

to immediately continue with the trial and determination of the

election protest before it on the merits.

Crespo v. Provincial Board, 160 SCRA 66

Doctrine: An order of suspension, without opportunity

for hearing, violates property rights

FACTS: Gregorio T. Crespo was elected Municipal Mayor of

Cabiao, Nueva Ecija, in the local elections of 1967. On January

25, 97, an administrative complaint was filed against him by

private respondent Pedro T. Wycoco for harassment, abuse of

authority and oppression. As required, petitioner filed a written

explanation as to why he should not be dealt with

administratively, with the Provincial Board of Nueve Ecija, in

accordance with Section 5, Republic Act No. 5185. However, on

February 15, 1971, without notifying Crespo or his counsel, the

board proceeded with the hearing and allowed private

respondent Pedro Wycoco to present evidence, and thereafter,

the board issued Resolution No. 51 ordering a preventive

suspension against petitioner mayor Crespo. This was assailed

by petitioner arbitrary, high-handed, atrocious, shocking and

grossly violative of Section 5 of Republic Act No. 5185 which

requires a hearing and investigation, and grossly violated the

due process.

ISSUE: W/N petitioner mayor was deprived with due process.

HELD: Yes, the order of preventive suspension was

issued without giving the petitioner a chance to be

heard. To controvert the claim of petitioner that he was not

fully notified of the scheduled hearing, respondent Provincial

Board, in its Memorandum, contends that "Atty. Bernardo M.

Abesamis, counsel for the petitioner mayor made known by a

request in writing, sent to the Secretary of the Provincial Board

his desire to be given opportunity to argue the explanation of

the said petitioner mayor at the usual time of the respondent

Board's meeting, but unfortunately, inspire of the time allowed

for the counsel for the petitioner mayor to appear as requested

by him, he failed to appeal." The contention of the Provincial

Board cannot stand alone in the absence of proof or evidence

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 2

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

to support it. The assailed order was issued mainly on the basis

of the evidence presented ex parte by respondent Wycoco, and

nothing therein can be gathered that the written explanation

submitted by petitioner was taken into account.

Republic vs. Rosemore Mining and Development

Corporation,

G.R. 149927, March 30, 2004

Doctrine: A mining license that contravenes a

mandatory provision of law under which it is granted is

void. Being a mere privilege, a license does not vest

absolute rights in the holder. Thus, without offending

the due process and the non-impairment clauses of the

Constitution, it can be revoked by the State in the

public interest

Facts: Petitioner Rosemoor Mining and Development

Corporation after having been granted permission to prospect

for marble deposits in the mountains of Biak-na-Bato, San

Miguel, Bulacan, succeeded in discovering marble deposits of

high quality and in commercial quantities in Mount Mabio which

forms part of the Biak-na-Bato mountain range.

The petitioner then applied with the Bureau of

Mines, now Mines and Geosciences Bureau, for the

issuance of the corresponding license to exploit said

marble deposits.

License No. 33 was issued by the Bureau of Mines in favor

of the herein petitioners. Shortly thereafter, Respondent

Ernesto Maceda cancelled the petitioners license stating

that their license had illegally been issued, because it violated

Section 69 of PD 463; and that there was no more public

interest served by the continued existence or renewal of the

license. The latter reason was confirmed by the language of

Proclamation No. 84. According to this law, public interest

would be served by reverting the parcel of land that was

excluded by Proclamation No. 2204 to the former status of that

land as part of the Biak-na-Bato national park.

Issue: Whether or not Presidential Proclamation No. 84 is valid.

Held: Yes. We cannot sustain the argument that Proclamation

No. 84 is a bill of attainder; that is, a legislative act which

inflicts punishment without judicial trial. Its declaration

that QLP No. 33 is a patent nullity is certainly not a declaration

of guilt. Neither is the cancellation of the license a punishment

within the purview of the constitutional proscription against

bills of attainder.

Too, there is no merit in the argument that the

proclamation is an ex post facto law. It is settled that an ex

post facto law is limited in its scope only to matters

criminal in nature. Proclamation 84, which merely restored

the area excluded from the Biak-na-Bato national park by

canceling respondents license, is clearly not penal in

character.

Also at the time President Aquino issued Proclamation No.

84 on March 9, 1987, she was still validly exercising legislative

powers under the Provisional Constitution of 1986. Section 1 of

Article II of Proclamation No. 3, which promulgated the

Provisional Constitution, granted her legislative power until a

legislature is elected and convened under a new Constitution.

The grant of such power is also explicitly recognized and

provided for in Section 6 of Article XVII of the 1987

Constitution.

Pedro vs. Provincial Board of Rizal, 53 Phil 123

Doctrine: Mere privileges, such as the license to

operate a cockpit, are not property rights and are

revocable at will

FACTS:

Petitioner Gregorio Pedro assails the validity of

Ordinance No. 36, series 1928 which was approved by

the temporary councilors appointed by the provincial

governor of Rizal, Eligio Naval.

Petitioner contends that the ordinance should be declared

null and void on the following grounds:

1. It impairs his acquired rights;

2. It was enacted on account of prejudice considering

that the ordinance is purposely enacted for a special

purpose, namely, to prevent, at any cost, the

opening, maintenance, and exploitation of the

cockpit of the said petitioner-appellant; and

3. It provides for special committee composed of

persons who are not

members of the council.

Hence, they are not accorded with the power to act

like the other Councilors.

Pedro further asserts that having obtained the proper

permit in order for him to maintain, exploit and open to

the public the cockpit in question, and having paid the

license for the same, he was able to fulfill all the

requirements provided by Ordinance No. 35, series of

1928. Hence, Pedro sticks firm to his belief that he already

acquired a right which cannot be taken away from him by

Ordinance No. 36.

ISSUE: Whether or not a license authorizing the operation and

exploitation of a cockpit falls under the property rights which a

person may not be deprived without due process of law.

HELD: No; a license authorizing the operation and exploitation

of a cockpit does NOT fall under the property rights which

a person may not be deprived without due process of law.

The Court held that a license authorizing the operation

and exploitation of a cockpit is a mere privilege which may be

revoked when the public interests so require. The special

committee composed of persons who are not members of the

council are NOT performing a legislative act. The work

entrusted to them by the municipal council is only

informational. Further, the ordinance, which was approved by a

municipal council duly constituted, that suspends the effects of

another which had been enacted to favor the grantee of a

cockpit license, is valid and legal.

G.R. No. 157036 June 9, 2004 (431 SCRA 534)

FRANCISCO CHAVEZ VS. HON. ALBERTO ROMULO AS

EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, PNP CHIEF HERMOGENES

EBDANE

Doctrine: The license to carry a firearm is neither a

property nor a property right. Neither does it create a

vested right. A permit to carry a firearm outside ones

residence may be revoked at any time. Even if it were a

property right, it cannot be considered as absolute as

to be placed beyond the reach of police power

FACTS: This case is about the ban on the carrying of

firearms outside of residence in order to deter the rising

crime rates. Petitioner questions the ban as a violation

of his right to property.

Chavez is a gun- owner who filed a petition for prohibition

and injunction seeking to enjoin the implementation of the

Guidelines in the Implementation of the Ban on the

Carying of Firearms Outside of Residence issued by PNP

Chief Hermogenes Ebdane, Jr. In January 2003, Pres. Arroyo

delivered a speech before the members of the PNP

stressing the need for a nationwide gun ban in all public

places to avert the rising crime incidents. She directed PNP

Chief Ebdane to suspend the issuance of permits to carry

firearms outside of residence (PTCFOR). Thus, Chief

Ebdane issued the assailed Guidelines. Chavez contends

that such guidelines was a derogation of his constitutional

right to life and to protect life as he, being a law-abiding

licensed gun-owner is the only class subject to the

implementation

while

leaving

the

law-breakers

(kidnappers, MILF, hold-uppers, robbers etc.) untouched.

Petitioner also averred that ownership and carrying of

firearms are constitutionally protected property rights

which cannot be taken away without due process of law.

ISSUES:

1.

WON the citizens right to bear arms is a constitutional

right

2.

WON the revocation of the PTCFOR pursuant to the

assailed Guidelines is a violation of right to property

3.

WON the issuance of said Guidelines is a valid exercise of

Police power

HELD:

1.

SC ruled that nowhere fond in our Constitution is the

provision on bearing arms as a constitutional right.

The right to bear arms, then, is a mere statutory

privilege unlike in the American Constitution which was

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 3

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

2.

3.

the law invoked by petitioner. Right to bear arms is a mere

statutory creation as was observed by the laws passed to

regulate the use, acquisition, transfer, importation of

firearms; it cannot be considered an inalienable or

absolute right.

The bulk of jurisprudence is that a license authorizing a

person to enjoy a certain privilege is neither a property

nor property right. A license is merely a privilege to do

what otherwise would be unlawful, and is not a contract

between the granting authority and the person to whom it

is granted; neither is it property right nor does it create a

vested right. Such license may be revoked anytime when

the authority deems it fit to do so, and such revocation

does not deprive the holder of any property, or immunity.

The test to determine the validity of police measure

, thus:

The interests of the public generally, as

distinguished from those of a particular class,

require the exercise of the police power; and

The means employed are reasonably necessary

for the accomplishment of the purpose and not

unduly oppressive upon individuals. It is apparent

from the assailed Guidelines that the basis for its

issuance was the need for peace and order in the

society. Owing to the proliferation of crimes,

particularly those committed by NPA, which tends to

disturb the peace of the community, Pres. Arroyo

deemed it best to impose a nationwide gun ban.

Undeniably, the motivating factor in the issuance of

guidelines is the interest of the public in general. Such

means of revocation is, thus, a valid exercise of police

power.

Petition is hereby dismissed.

Libanan v. Sandiganbayan, 233 SCRA 163

Doctrine: The mandatory suspension from office of a

public official pending criminal prosecution for violation

of RA 3019 cannot amount to deprivation of property

without due process of law

Canlas vs. Napico Homeowners, G.R. No. 182795, June 5,

2008

Facts: Petitioners are settlers in a certain parcel of land

situated in the Brgy. Manggahan, Pasig City. Their dwellings

have either been demolished as of the time of filing of the

petition, or is about to be demolished pursuant to a court

judgment. Petitioners claim that respondents hold fraudulent

and spurious titles. Thus, the petition for writ of amparo. The

rule on writ of amparo is a remedy available to any person

whose right to life, liberty and security is violated or threatened

with violation by an unlawful act or omission of a public official

or employee or of a private individual or entity. The writ shall

cover extra legal killings or disappearances.

Issue: WON the writ of amparo is a correct remedy for the

petitioners.

Ruling: No. The writ of amparo does not cover the

cause of the petitioners. The threatened demolition of a

dwelling by a virtue of a final judgment of the court is not

included among the enumeration of rights covered by the writ.

Also, the factual and legal basis for petitioners claim to the

land in question is not alleged at all in the petition

Luque vs. Villegas, G.R. No. L-22545, November 28,

1969

Facts: Petitioners (who are passengers from Cavite and

Batangas who ride on buses to and from their province and

Manila) and some public service operators of buses and jeeps

assail the validity of Ordinance 4986and Administrative Order

1.

Ordinance 4986 states that PUB and PUJs shall be allowed

to enter Manila only from 6:30am to 8:30pm every day except

Sundays and holidays.

Petitioners contend that since they possess a valid CPC,

they have already acquired a vested right to operate.

Administrative Order 1 issued by Commissioner of Public

Service states that all jeeps authorized to operate from Manila

to any point in Luzon, beyond the perimeter of Greater Manila,

shall carry the words "For Provincial Operation".

Issue: W/N Ordinance 4986 destroys vested rights to operate

in Manila

Held: NO! A vested right is some right or interest in the

property which has become fixed and established and is

no longer open to doubt or controversy. As far as the

State is concerned, a CPC constitutes neither a franchise nor a

contract, confers no property right, and is a mere license or

privilege.

The holder does not acquire a property right in the route

covered, nor does it confer upon the holder any proprietary

right/interest/franchise in the public highways.

Neither do bus passengers have a vested right to be

transported directly to Manila. The alleged right is dependent

upon the manner public services are allowed to operate within

a given area. It is no argument that the passengers enjoyed the

privilege of having been continuously transported even before

outbreak of war. Times have changed and vehicles have

increased. Traffic congestion has moved from worse to critical.

Hence, there is a need to regulate the operation of public

services.

3.

a.

Aspects of due process

Substantive due process - This serves as a

restriction on government's law- and rulemaking

powers

The requisites are:

1. The interests of the public, in general, as

distinguished from those of a particular class,

require the intervention of the State.

2. The means employed are reasonably necessary for

the accomplishment of the purpose, and not unduly

oppressive on individuals

US vs. Toribio, 15 Phil 85

FACTS: Appellant in the case at bar was charged for the

violation of sections 30 & 33 of Act No. 1147, an Act regulating

the registration, branding, and slaughter of large cattle.

Evidence sustained in the trial court found that appellant

slaughtered or caused to be slaughtered for human

consumption, the carabao described in the information, without

a permit from the municipal treasurer of the municipality where

it was slaughtered. Appellant contends that he applied for a

permit to slaughter the animal but was not give none because

the carabao was not found to be unfit for agricultural work

which resulted to appellant to slaughter said carabao in a place

other than the municipal slaughterhouse. Appellant then assails

the validity of a provision under Act No. 1147 which states that

only carabaos unfit for agricultural work can be slaughtered.

ISSUE: W/N Act No. 1147 is constitutional.

HELD: Yes. The provision of the statute in question being a

proper exercise of police power is not a violation of the terms of

Section 5 of the Philippine Bill; a provision which itself is

adopted from the Constitution of US; and is found in substance

in the Consititution of most if not all of the States of the Union.

Churchill vs. Rafferty, 32 Phil 580

FACTS: Plaintiffs put up a billboard on private land in Rizal

Province "quite a distance from the road and strongly built".

Someresidents (German and British Consuls) find it offensive.

Act # 2339 allows the defendent, the Collector of

InternalRevenue, to collect taxes from such property and to

remove it when it is offensive to sight. Court of first

Instanceprohibited the defendant to collect or remove the

billboard

ISSUE:

1. W/N the courts may restrain by injunction the collection of

taxes

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 4

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

2. Is Act # 2339 unconstitutional because it deprives property

without due process of law in allowing CIR to remove it if it

is offensive

HELD:

1. An injunction is an extraordinary remedy and not to be used

if there is an adequate remedy provided by law; here there

is an adequate remedy, therefore court may not do so.

2. Unsightly advertisements which are offensive to the sight

are not dissociated from the general welfare of the public,

therefore can be regulated by police power, and act is

constitutional.

Rubi vs. Provincial Board of Mindoro, 39 Phil 660

Doctrine: Liberty regulated by law": Implied in the

term is restraint by law for the good of the individual

and for the greater good of the peace and order of

society and the general well-being. No man can do

exactly as he pleases

FACTS: Petitioner

Rubi

and

other

Mangyanes

were

recommended by the Provincial Governor of Mindoro to take

their habitation on an unoccupied land of Tigbao on Naujan

Lake to remain there, or be punished by imprisonment if they

run. The Mangyanes had to stay there for a reason of

cultivation under certain plans. Over 300 Mangyanes were

confined on a 800 hectares whereas the land is under the

resolution of the Provincial Board. Then Dabalos, one of the

Mangyanes, was taken by the provincial sheriff and imprisoned

him at Calapan solely because he escaped from the

reservation. Habeas Corpus was made on behalf of Rubi and

the Mangyans for an application that alleged the virtue of the

resolution of the provincial board creating the reservation

whereas they had been illegally deprived of their liberty. The

validity of Sec.2145 of the Administrative Code was challenged.

ISSUE: WON Section 2145 of the Administrative Code deprives

a person of his liberty of abode.

HELD: The Court held that section 2145 of the Administrative

Code does not deprive a person of his liberty of abode and

does not deny to him the equal protection of the laws, and that

confinement in reservations in accordance with said section

does not constitute slavery and involuntary servitude. The

Court is further of the opinion that section 2145 of the

Administrative Code is a legitimate exertion of the police

power. Section 2145 of the Administrative Code of 1917 is

constitutional. Assigned as reasons for the action: (1) attempts

for the advancement of the non-Christian people of the

province; and (2) the only successfully method for educating

the Manguianes was to oblige them to live in a permanent

settlement. The Solicitor-General adds the following; (3) The

protection of the Manguianes; (4) the protection of the public

forests in which they roam; (5) the necessity of introducing

civilized customs among the Manguianes. One cannot hold that

the liberty of the citizen is unduly interfered without when the

degree of civilization of the Manguianes is considered. They are

restrained for their own good and the general good of the

Philippines.

Binay vs. Domingo, G.R. No. 92389, September 11, 1991

Facts: Petitioner Municipality of Makati, through its Council,

approved Resolution No. 60 which extends P500 burial

assistance to bereaved families whose gross family income

does not exceed P2,000.00 a month. The funds are to be taken

out of the unappropriated available funds in the municipal

treasury. The Metro Manila Commission approved the

resolution. Thereafter, the municipal secretary certified a

disbursement of P400,000.00 for the implementation of the

program. However, the Commission on Audit disapproved said

resolution and the disbursement of funds for the

implementation thereof for the following reasons: (1) the

resolution has no connection to alleged public safety, general

welfare, safety, etc. of the inhabitants of Makati; (2)

government funds must be disbursed for public purposes only;

and, (3) it violates the equal protection clause since it will only

benefit a few individuals.

Issues:

1. Whether Resolution No. 60 is a valid exercise of the police

power under the general welfare clause

2. Whether the questioned resolution is for a public purpose

3. Whether the resolution violates the equal protection clause

1.

Police power is inherent in the state but not in

municipal corporations. Before a municipal corporation may

exercise such power, there must be a valid delegation of such

power by the legislature which is the repository of the

inherent powers of the State. Municipal governments exercise

this power under the general welfare clause.

2.

Public purpose is not unconstitutional merely because

it incidentally benefits a limited number of persons. As

correctly pointed out by the Office of the Solicitor General,

"the drift is towards social welfare legislation geared towards

state policies to provide adequate social services, the

promotion of the general welfare, social justice as well as

human dignity and respect for human rights." The care for

the poor is generally recognized as a public duty. The support

for the poor has long been an accepted exercise of police

power in the promotion of the common good.

3.

There is no violation of the equal protection

clause. Paupers may be reasonably classified. Different

groups may receive varying treatment. Precious to the hearts

of our legislators, down to our local councilors, is the welfare

of the paupers

Agcaoili vs. Felipe, 149 SCRA 341

Lupangco vs. Court of Appeals, 160 SCRA 848

Facts: On or about October 6, 1986, herein respondent

Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) issued Resolution

No. 105 as parts of its "Additional Instructions to Examinees,"

to all those applying for admission to take the licensure

examinations in accountancy.

No examinee shall attend any review class, briefing,

conference or the like conducted by, or shall receive any handout, review material, or any tip from any school, college or

university, or any review center or the like or any reviewer,

lecturer, instructor official or employee of any of the

aforementioned or similar institutions during the three days

immediately preceding every examination day including

examination day.

Any examinee violating this instruction shall be subject to

the sanctions prescribed by Sec. 8, Art. III of the Rules and

Regulations of the Commission

On October 16, 1986, herein petitioners, all reviewees

preparing to take the licensure examinations in accountancy

schedule on October 25 and November 2 of the same year,

filed on their own behalf of all others similarly situated like

them, with the Regional Trial Court of Manila a complaint for

injunction with a prayer with the issuance of a writ of a

preliminary injunction against respondent PRC to restrain the

latter from enforcing the above-mentioned resolution and to

declare the same unconstitutional.

Respondent PRC filed a motion to dismiss on October 21,

1987 on the ground that the lower court had no jurisdiction to

review and to enjoin the enforcement of its resolution

In an Order of October 21, 1987, the lower court declared

that it had jurisdiction to try the case and enjoined the

respondent commission from enforcing and giving effect to

Resolution No. 105 which it found to be unconstitutional

Not satisfied therewith, respondent PRC, on November 10,

1986, filed with the Court of Appeals

Issue: Whether or not the PRC resolution violates substantive

due process

Held: Yes. Resolution No. 105 is not only unreasonable and

arbitrary, it also infringes on the examinees' right to liberty

guaranteed by the Constitution. Respondent PRC has no

authority to dictate on the reviewees as to how they should

prepare themselves for the licensure examinations. They

cannot be restrained from taking all the lawful steps needed to

assure the fulfilment of their ambition to become public

accountants. They have every right to make use of their

faculties in attaining success in their endeavors. They should

be allowed to enjoy their freedom to acquire useful knowledge

that will promote their personal growth

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 5

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

Balacuit vs. Court of First Instance, 163 SCRA 182

FACTS: This involves a Petition for Review questioning the

validity and constitutionality of Ordinance No.640 passed by

the Municipal Board of the City of Butuan on April 21, 1969,

penalizing any person, group of persons, entity or

corporation engaged in the business of selling

admission tickets to any movie or other public

exhibitions, games, contests or other performances to

require children between 7 and 12years of age to pay

full payment for tickets intended for adults but should

charge only one-half of the said ticket. Petitioners who are

managers of theaters, affected by the ordinance, filed a

Complaint before the Court of First Instance of Agusan del

Norte and Butuan City docketed as Special Civil No. 237 on

June 30,1969, praying that the subject ordinance be declared

unconstitutional and, therefore, void and unenforceable. The

Court rendered judgment declaring Ordinance No. 640 of the

City of Butuan constitutional and valid.

ISSUE: Whether Ordinance No. 640 passed by the Municipal

Board of the City of Butuan is valid and constitutional and was

the Ordinance a valid exercise of police power

HELD: NO. Ordinance No. 640 is declared unconstitutional. The

exercise of police power by the local government is valid unless

it contravenes the fundamental law of the land, or an act of the

legislature, or unless it is against public policy or is

unreasonable, oppressive, partial, discriminating or in

derogation of a common right. For being unreasonable and an

undue restraint of trade, it cannot, under the guise of

exercising police power, be upheld as valid.

BANAT vs. Comelec, 595 SCRA 477

Facts: The case is a Special Civil action filed by BANAT

(Barangay Association for National Advancement and

Transparency) party-list, a duly accredited multi-sectoral

organization, assailing the constitutionality of R.A. 9363 and

enjoining the COMELEC and from implementing the statute.

R.A. 9363 is a consolidation of Senate bill and House bill passed

by the Senate and signed by the President.

Issue: W/N R.A. 9363 constitutional?

Ruling: The petition was dismissed for lack of merit.

Topic related discussion:

STATUTES It is settled that every statute is

presumed to be constitutional. The presumption is that the

legislature intended to enact a valid, sensible and just law.

Those who petition the Court to declare a law unconstitutional

must show that there is a cleared and unequivocal breach of

the Constitution, not merely a doubtful, speculative or

argumentative one; otherwise, the petition must fail.

TITLE OF BILLS The constitutional requirement

that every bill passed by the Congress shall embrace

shall embrace o0nly one subject which shall be

expressed in the title thereof has always been given a

practical rather than technical construction. The requirement is

satisfied if the title is comprehensive enough to include

subjects related to the general purpose which he statute seeks

to achieve. A title which declares a statue to be an act amends

a specified code is sufficient and the precise nature of the

amendatory ct need not be further stated.

People vs. Siton, 600 SCRA 476

FACTS: Siton et al. were charged with vagrancy pursuant to

Art. 202(2) of theRPC.1 They filed separate motions to quash

on the ground that Art. 202(2) is unconstitutional for being

vague and overbroad. The MTC denied the motions and

declared that the law on vagrancy was enacted pursuant to the

States police power and justified by the maximsalus populi

est suprema lex. The MTC also noted that in the affidavit of

the arresting officer it was stated that there was a

prior

surveillance conducted on Siton et al. in an area

reported to be frequented by vagrants and prostitutes who

solicited sexual favors. Siton et al. thus filed an original petition

for certiorari and prohibition with the RTC, directly challenging

the constitutionality of Art. 202(2). Siton et al.s position:(1)

The definition is vague. The definition results in an arbitrary

identification of violators (the definition includes persons who

are otherwise performing ordinary peaceful acts) (3) Art. 202(2)

violated the equal protection clause because it discriminates

against the poor and unemployed The OSG argued that the

over breadth and vagueness doctrines apply only to free

speech cases. It also asserted that Art. 202(2) must be

presumed valid and constitutional. Siton et al. failed to

overcome this presumption. The trial court declared Art. 202

(2) as unconstitutional for being vague and for violating the

equal protection clause. Citing Papachristou v. City of

Jacksonville, it held that the void for vagueness

doctrine is equally applicable in testing the validity of penal

statutes.3 The court also held that the application of Art.

202(2), crafted in the 1930s, to our situation at present runs

afoul of the equal protection clause as it offers no

reasonable classification. Since the definition of vagrancy

under the provision offers no reasonable indicators to

differentiate those who have no visible means of support by

force of circumstance and those who choose to loiter about and

bum around, who are the proper subjects of vagrancy

legislation, it cannot pass a judicial scrutiny of its

constitutionality.

ISSUE: Whether or not Art. 202(2) is unconstitutional.

OSGs position:(1) Every law is presumed valid and all

reasonable doubts should be resolved in favor of its

constitutionality(2) The overbreadth and vagueness doctrines

have special application to free-speech cases only and are not

appropriate for testing the validity of penal statutes (3) Siton et

al. failed to overcome the presumed validity of the statute(4)

The State may regulate individual conduct for the promotion of

public welfare in the exercise of its police power

Siton et al.s position :(1) Art. 202(2) on its face violates the

due process and the equal protection clauses (2) The due

process vagueness standard, as distinguished from the

free speech vagueness doctrine, is adequate to declare Art.

202(2) unconstitutional and void on its face(3) The presumption

of constitutionality was adequately overthrown

HELD: CONSTITUTIONAL. The power to define crimes and

prescribe their corresponding penalties is legislative in nature

and inherent in the sovereign power of the state as an aspect

of police power. Police power is an inherent attribute

of

sovereignty. The power is plenary and its scope is vast

andpervasive, reaching and justifying measures for public

health, public safety, public morals, and the general welfare.

As a police power measure, Art.202(2) must be viewed in a

constitutional light

White Light Corporation vs. City of Manila, 576 SCRA

416

Facts: On December 3, 1992, City Mayor Alfredo S. Lim signed

into law and ordinance entitled An Ordinance Prohibiting Shorttime Admission, Short-time Admission Rates, and Wash-up

Schemes in Hotels, Motels, Inns, Lodging Houses, and Similar

Establishments in the City of Manila. On December 15, 1992,

the Malate Tourist and Development Corporation (MTDC) filed a

complaint for declaratory relief with prayer for a writ of

preliminary injunction and/or temporary restraining order (TRO)

with the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 9 and prayed

that the Ordinance be declared invalid and unconstitutional. On

December 21, 1992, petitioners White Light Corporation,

Titanium Corporation and Sta. Mesa Tourist Development

Corporation filed a motion to intervene, which was granted by

the RTC. MTDC moved to withdraw as plaintiff which was also

granted by the RTC. On January 14, 1993, the RTC issued a TRO

directing the City to cease and desist from enforcing the

Ordinance. On October 20, 1993, the RTC rendered a decision

declaring the Ordinance null and void. The City then filed a

petition for review on certiorari with the Supreme Court.

However, the Supreme Court referred the same to the Court of

Appeals. The City asserted that the Ordinance is a valid

exercise of police power pursuant to Local government code

and the Revised Manila charter. The Court of Appeals reversed

the decision of the RTC and affirmed the constitutionality of the

Ordinance.

Issue: Whether the Ordinance is constitutional.

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 6

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

Held: No, it is not constitutional. The apparent goal of the

Ordinance is to minimize if not eliminate the use of the covered

establishments for illicit sex, prostitution, drug use and the like.

These goals, by themselves, are unimpeachable and certainly

fall within the ambit of the police power of the State. Yet the

desirability of these ends does not sanctify any and all means

for their achievement. However well-intentioned the Ordinance

may be, it is in effect an arbitrary and whimsical intrusion into

the rights of the establishments as well as their patrons. The

Ordinance needlessly restrains the operation of the businesses

of the petitioners as well as restricts the rights of their patrons

without sufficient justification.

b.

Procedural due process This serves as a

restriction on actions of judicial and quasijudicial

agencies of government

Requisites: (Judicial Due Process) IJHJ

1. I Impartial and Competent Court clothed with

judicial power to hear and determine the matter

before it

2. J Jurisdiction lawfully acquired over the person of

the defendant and/or property

3. H Hearing (defendant must be given opportunity to

be heard)

Cases in which notice and hearing may be

dispensed without violating due process:

1. Abatement of nuisance per se

2. Preventive suspension of a civil servant

facing admin charges

3.

Cancellation of passport of a person

sought for commission of crime

4. Statutory presumptions

4. J Judgment rendered upon lawful hearing

G.R. No. 126995, October 6, 1998

Imelda Romualdez-Marcos vs. Sandiganbayan

Doctrine: when the Court cross-examined the accused

and witnesses, it acted with over-zealousness,

assuming the role of both magistrate and advocate, and

thus denied the accused due process of law

Rivera vs. Civil Service Commission, 240 SCRA 43

Doctrine: A public officer who decided the case should

not be the same person to decide it on appeal because

he cannot be an impartial judge

FACTS: Petitioner was the manager of Corporate Banking Unit

of LBP and was charged with dishonesty, receiving for personal

use of fee, gift or other valuable thing in the course of official

duties, committing acts punishable under the Anti-Graft Laws,

and pursuit of private business vocation or profession without

permission required by CSC. Rivera allegedly told Perez that he

would facilitate the processing, approval and release of his loan

if he would be given 10% commission. Rivera was further

charged having served and acted, without prior authority

required by CSC, as the personal consultant of Lao and

consultant in various companies where Lao had investments.

LBP held Rivers guilty of grave misconduct and acts prejudicial

to the best interest of the service in accepting employment

from a client of the bank. The penalty of forced resignation,

without separation benefits and gratuities, was thereupon

imposed on Rivera.

Issue: Whether the CSC committed grave abuse of discretion

in composing the capital penalty of dismissal on the basis of

unsubstantiated finding and conclusions (violation of

substantive due process)

Ruling: Yes. Given the circumstances in the case at bench, it

should have behooved Commissioner Gaminde to inhibit

herself totally from any participation in resolving Riveras

appeal to CSC to give full meaning and consequence to a

fundamental aspect of due process. CSC resolution is SET

ASIDE and the case is remanded to CSC for the resolution, sans

the participation of CSC Commissioner Gaminde, as she was

the Board Chairman of MSPB whose ruling is thus appealed

People vs. Medenilla, G.R. No. 131638-39, March 26,

2001

Doctrine: even as the transcript of stenographic notes

showed that the trial court intensively questioned the

witnesses (approximately 43% of the questions asked of

prosecution

witnesses

and

the

accused

were

propounded by the judge), the Supreme Court held that

the questioning was necessary. Judges have as much

interest as counsel in the orderly and expeditious

presentation of evidence, and have the duty to ask

questions that would elicit the facts on the issues

involved, clarify ambiguous remarks by witnesses, and

address the points overlooked by counsel.

Facts: On 16 April 1996, Loreto Medenilla y Doria was caught

for illegal possession and unlawfully selling 5.08g of

shabu (Criminal Case 3618-D), was in unlawful possession of 4

transparent plastic bags of shabu weighing 200.45g (Criminal

Case 3619-D) in Mandaluyong City. Versions of facts leading to

the arrest are conflicting; the prosecution alleging buy-bust

operations, while defense claim illegal arrest, search and

seizure. Arraigned on 25 June 1996, Medenilla pleaded not

guilty. The judge therein, for the purpose of clarification,

propounded a question upon a witness during the trial. On 26

November 1997, the Regional Trial Court of Pasig (Branch 262)

found Medenilla, in Criminal Cases 3618-D and 3619-D, guilty

beyond reasonable doubt of violating Sections 15 and 16 of RA

6425, as amended (Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972).

Issue: Whether judges are allowed to asked clarificatory

questions.

Held: YES. A single noted instance of questioning cannot

justify a claim that the trial judge was biased. The Court have

exhaustively examined the transcript of stenographic notes and

determined that the trial judge was more than equitable in

presiding over the hearings of this case. Moreover, a judge is

not prohibited from propounding clarificatory questions on a

witness if the purpose of which is to arrive at a proper and just

determination of the case. The trial judge must be

accorded a reasonable leeway in putting such questions

to witnesses as may be essential to elicit relevant facts

to make the record speak the truth. It cannot be taken

against him if the clarificatory questions he propounds

happen to reveal certain truths which tend to destroy

the theory of one party.

G.R. No. 144464, November 22, 2001

Cruz vs. Civil Service Commission,

The Court rejected petitioners' contention that they

were denied due process ostensibly because the Civil

Service Commission acted as investigator, complainant,

prosecutor and judge. The CSC is mandated to hear and

decide administrative cases instituted by it or instituted

before it directly or on appeal. Neither can it be denied

that petitioners were formally charged after a prima

facie case for dishonesty was found to exist. They were

properly informed of the charges. They submitted an

answer and were given the opportunity to defend

themselves

FACTS: On September 9, 1994 it was discovered by the Civil

Service Commission that Paitim, Municipal Treasurer of Bulacan

took the non-professional examination for Cruz after the latter

had previously failed in the said examination three times.

The CSC found after a fact finding investigation that a

prima facie case exists against youfor DISHONESTY, GRAVE

MISCONDUCT

and

CONDUCT

PREJUDICIAL

TO

THE

BESTINTEREST OF THE SERVICE.

The petitioners filed their Answer to the charge entering a

general denial of the material averments of the "Formal

Charge." They also declared that they were electing a formal

investigation on the matter. The petitioners subsequently filed

a Motion to Dismiss averring that if the investigation will

continue, they will be deprived of their right to due process

because the Civil Service Commission was the complainant, the

Prosecutor and the Judge, all at the same time. On November

16, 1995, Dulce J. Cochon issued an "Investigation Report and

Recommendation" finding the Petitioners guilty of "Dishonesty"

and ordering their dismissal from the government service.

Petitioners maintain that the CSC did not have original

jurisdiction to hear and decide the administrative case.

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 7

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

Allegedly, in accordance with Section 47(1), Chapter 7, Subtitle

A, Title 1,Book V, Administrative Code of 1987, the CSC is

vested with appellate jurisdiction only in all administrative

cases where the penalty imposed is removal or dismissal from

the office and where the complaint was filed by a private

citizen against the government employee.

ISSUE: Whether or not petitioners right to due process was

violated when the CSC acted as investigator, complainant,

prosecutor and judge all at the same time.

HELD: NO. The fact that the complaint was filed by the CSC

itself does not mean that it could not be an impartial judge. As

an administrative body, its decision was based on substantial

findings. Factual findings of administrative bodies, being

considered experts in their field, are binding on the Supreme

Court. The records clearly disclose that the petitioners were

duly investigated by the CSC. After a careful examination of the

records, the Commission finds respondents guilty as charged.

The photograph pasted over the name Gilda Cruz in the Picture

Seat Plan (PSP) during the July 30, 1989 Career Service

Examination is not that of Cruz but of Paitim. Also, the

signature over the name of Gilda Cruz in the said document is

totally different from the signature of Gilda Cruz.

G.R. No. 76761, January 9, 1989

Assistant Executive Secretary vs. Court of Appeals,

Facts: On April 15, 1948, Jesus Larrabaster applied with the

National Land Settlement Administration (NLSA) for a home lot

at the Marbel Settlement District, Cotabato. Larrabasters

application was granted on July 10, 1950 with a Home Lot

Number 336 (later known as 335) with an area of 1,500 square

meters.

Larrabaster then leased the lot to private respondent

Basilio Mendoza and tolerated Jorge Geller to squat on the

portion thereof. On November 25, 1952, the Land Settlement

and Development Corporation (LASEDECO) took over the

functions of NLSA.

On June 29, 1956, Larrabaster and his wife assigned their

rights and interests over the Disputed Property to Jose Pena.

Pena allowed Mendoza and Geller to stay on the lot. On

September 1956, a supplementary Deed of Sale was executed

by the same parties defining the boundaries of the disputed

property.

On June 18, 1954, R.A No. 1160 transferred the custody

and administration of the MarbelTownsite to the National

Rehabilitation Administration (NARRA). Pena requested NARRA

to approve the transfer of rights that the parties indicated but

the latter did not approve such request in view of Proclamation

Number 336, series of 1956, returning to the Bureau of Lands

the disposition of lands which remained unallocated by the

LASEDECO at the time of its abolition.

The Bureau of Lands did not act on Penas request either,

prompting him to bring up the matter to the Board of

Liquidators (BOL). Pena must have realized that the Disputed

Property contained an area bigger than 1,500 sq. meters, he

request to BOL that the area be adjusted from 1,500 to

3,616.93 sq. meters to conform to its actual area. Pena moved

for reconsideration stressing that the land should be entitled to

him, but BOL again denied the request under its Resolution No.

439, series of 1967. Pena then appealed to the Office of the

President. The Office of the President asked the BOL to conduct

investigation on the disputed property. BOL then recommended

that Pena be awarded the Lot. No. 108 instead of the whole

former Lot Number 355. Pena alleged that the lot transferred to

him contains 3,616.93 and not 1,500 sq. meters. Upon Penas

motion for reconsideration, the same office modified its

decision awarding to Pena of the original Lot Number 355 is

hereby maintained.

On August 1, 1969, private respondent Basilio Mendoza

addressed a letter of protest to the BOL, to which the latter

responded by advising Mendoza to direct its protest to the

Office of the President.

Mendoza did so and on September 28, 1971, said office

rendered its letter-decision, affirming its previous decision of

May 13, 1969, having found no cogent reason to depart

therefrom. In the meantime, on January 17, 1970, and while the

protest with the office of the president was still pending,

Mendoza resorted to Civil Case Number 98 for certiorari before

then the Court of First Instance of Cotabato against petitionerpublic officials and Pena. On June 23m 1978, Mendoza followed

up with a Supplementary Petition to annul the administrative

decision of September 20, 1971 denying his protest. On May

10, 1985, the trial court rendered its decision in Civil Case no.

98, dismissing Mendozas petition for Certiorari.

Issue: Whether or not private petitioner Basilio Mendoza was

denied with the due process of law

Ruling: Although there was a procedural defect because there

was an absence of notice and opportunity to be present in

administrative proceedings, the defect was cured when

Mendoza was allowed to file his letter-protest with the Office of

the President.The foregoing observations do not justify the

conclusion arrived at.

After the Office of the President had rendered its decision

on May 13, 1969, Mendoza filed a letter-protest on August 1,

1971 with the BOL. The latter office directed him to file his

protest with the Office of the President, which he did.

On September 28, 1972, Mendozas request for

consideration was denied by the said Office. So that, even

assuming that there was an absence of notice and opportunity

to be present in the administrative proceedings prior to the

rendition of the February 10, 1969 and May 19, 1969 decisions

by the Office of the President, such procedural defect was

cured when Mendoza elevated his letter-protest to the Office of

the President, which subjected the controversy to appellate

review but eventually denied reconsideration.

Having been given a chance to be heard with

respect to his protest there is a sufficient compliance

with the requirements of due process.

Bautista vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 157219, May 28,

2004

Doctrine: Where a party was afforded an opportunity to

participate in the proceedings but failed to do so, he

cannot complain of deprivation of due process.

Facts: On August 12, 1999, petitioners Natividad E. Bautista,

Clemente E. Bautista and Socorro L. Angeles filed a complaint

against respondent Manila Papermills, International, Inc. for

quieting of title. This complaint was later amended to implead

respondents Adelfa Properties, Inc. and the spouses Rodolfo

and Nelly Javellana. fter several delays spanning more than two

years, the case was finally set for trial. However, on May 2,

2002, petitioners filed an Urgent Motion for Postponement to

cancel the hearing on the ground that Atty. Michael Macaraeg,

the lawyer assigned to the case was in the United States

attending to an important matter. The trial court denied

petitioners motion for postponement and considered them as

having waived the presentation of their evidence.

Issue: Whether or not there is a violation to due process.

Ruling: No, due process is not violated. Petitioners contention

that they were denied due process is not well- taken. Where a

party was afforded an opportunity to participate in the

proceedings but failed to do so, he cannot complain of

deprivation of due process. Due process is satisfied as long as

the party is accorded an opportunity to be heard. If it is not

availed of, it is deemed waived or forfeited without violating

the constitutional guarantee. Mariveles Shipyard vs. Court of

Appeals, G.R. No. 144134, November 11, 2003

Chua vs. Court of Appeals, 278 SCRA 33

Doctrine: Denial of due process cannot be successfully

invoked by a party who has had the opportunity to be

heard on his motion for reconsideration.

Facts: From 1970 up to 1981, Roberto Chua lived out of

wedlock with private respondent Florita A. Vallejo and they

begot two sons. On 28 May 1992, Roberto Chua died intestate

in Davao City.

On 2 July 1992, Vallejo filed with the Regional Trial Court

of Cotabato City a petition for the guardianship and

administration over the persons and properties of the two

minors.

Petitioner Antonietta Garcia Vda. de Chua, representing to

be the surviving spouse of Roberto Chua, filed a Motion to

Dismiss on the ground of improper venue. Petitioner alleged

that at the time of the decedents death, Davao City was his

cazgo/ 03.06.16 / 8

University of Cebu College of Law (Constitutional Law 2 Course Outline 2)

Instructor: Atty. Ria Lidia G. Espina

residence, hence, the Regional Trial Court of Davao City is the

proper forum. In support of her allegation, petitioner presented

the following documents: (1) photocopy of the marriage

contract; (2) Transfer Certificate of Title issued in the name of

Roberto L. Chua married to Antonietta Garcia, and a resident of

Davao City; (3) Residence Certificates from 1988 and 1989

issued at Davao City indicating that he was married and was

born in Cotabato City; (4) Income Tax Returns for 1990 and

1991 filed in Davao City where the status of the decedent was

stated as married; and, (5) Passport of the decedent specifying

that he was married and his residence was Davao City.

Vallejo contends that movant/oppositor Antonietta Chua is

not the surviving spouse of the late Roberto L. Chua but a

pretender to the estate of the latter since the deceased never

contracted marriage with any woman until he died.

The trial court ruled that petitioner has no personality to

file the motion not having proven his status as a wife of the

decedent. The Order was appealed to the CA, but it decided in

favor of herein respondents. The petioner elevated the case to

the Supreme Court that the Court of Appeals erred in not

nullifying the orders precipitately issued ex- parte by the public

respondent Regional Trial Court in the intestate proceeding

without prior hearing or notice to herein petitioner thereby

depriving Antonietta Garcia Vda de Chua of the due process

and opportunity to be heard.

Issue: Whether or not the Petitioner was denied of the due

process?

Held: The petitioner was not denied of the due process.

Due process was designed to afford opportunity to be heard,

not that an actual hearing should always and indispensably be

held. The essence of due process is simply an opportunity to be

heard. Here, even granting that the petitioner was not notified

of the orders of the trial court inclusive, nonetheless, she was

duly heard in her motions to recall letters of administration and

to declare the proceedings of the court as a "mistrial," which

motions were denied in the Order dated 22 November 1993. A

motion for the reconsideration of this order of denial was also

duly heard by the trial court but was denied in its Order of 13

December 1993.

Suntay vs. People, 101 Phil 833

Facts: On 26 June 1954, Dr. Antonio Nubla, father of Alicia

Nubla, a minor of 16 years, filed a verified complaint against

Emilio Suntay in the Office of the City Attorney of Quezon City,

alleging that on or about 21 June 21954, the accused took

Alicia Nubla from St. Paul's College in Quezon City with lewd

design and took her to somewhere near the University of the

Philippines (UP) compound in Diliman and was then able to

have carnal knowledge of her. On 15 December 1954, after an

investigation, an Assistant City Attorney recommended to the

City Attorney of Quezon City that the complaint be dismissed

for lack of merit. On 23 December 1954 attorney for the

complainant addressed a letter to the City Attorney of Quezon

City wherein he took exception to the recommendation of the

Assistant City Attorney referred to and urged that a complaint

for seduction be filed against Suntay. On 10 January 1955,

Suntay applied for and was granted a passport by the

Department of Foreign Affairs (5981 [A39184]). On 20 January

1955, Suntay left the Philippines for San Francisco, California,

where he is at present enrolled in school. On 31 January 1955,

Alicia Nubla subscribed and swore to a complaint charging

Suntay with seduction which was filed, in the Court of First

Instance (CFI) Quezon City, after preliminary investigation had

been conducted (Criminal case Q-1596). On 9 February 1955

the private prosecutor filed a motion praying the Court to issue

an order "directing such government agencies as may be

concerned, particularly the National Bureau of Investigation

and the Department of Foreign Affairs, for the purpose of

having the accused brought back to the Philippines so that he

may be dealt with in accordance with law." On 10 February

1955 the Court granted the motion. On 7 March 1955 the

Secretary cabled the Ambassador to the United States

instructing him to order the Consul General in San Francisco to

cancel the passport issued to Suntay and to compel him to

return to the Philippines to answer the criminal charges against

him. However, this order was not implemented or carried out in

view of the commencement of this proceedings in order that

the issues raised may be judicially resolved. On 5 July 1955,

Suntays counsel wrote to the Secretary requesting that the

action taken by him be reconsidered, and filed in the criminal

case a motion praying that the Court reconsider its order of 10

February 1955. On 7 July 1955, the Secretary denied counsel's

request and on 15 July 1955 the Court denied the motion for

reconsideration. Suntay filed the petition for a writ of certiorari.

Issue: Whether Suntay should be accorded notice and hearing

before his passport may be cancelled.

Held: Due process does not necessarily mean or require

a hearing. When discretion is exercised by an officer

vested with it upon an undisputed fact, such as the

filing of a serious criminal charge against the passport

holder, hearing may be dispensed with by such officer

as a prerequisite to the cancellation of his passport;

lack of such hearing does not violate the due process of

law clause of the Constitution; and the exercise of the

discretion vested in him cannot be deemed whimsical

and capricious because of the absence of such hearing.

If hearing should always be held in order to comply with the

due process of law clause of the Constitution, then a writ of

preliminary injunction issued ex parte would be violative of the

said clause. Hearing would have been proper and necessary if

the reason for the withdrawal or cancellation of the passport

were not clear but doubtful. But where the holder of a passport

is facing a criminal charge in our courts and left the country to

evade criminal prosecution, the Secretary for Foreign Affairs, in

the exercise of his discretion (Section 25, EO 1, S. 1946, 42 OG

1400) to revoke a passport already issued, cannot be held to

have acted whimsically or capriciously in withdrawing and

cancelling such passport. Suntays suddenly leaving the

country in such a convenient time, can reasonably be

interpreted to mean as a deliberate attempt on his part to flee

from justice, and, therefore, he cannot now be heard to

complain if the strong arm of the law should join together to

bring him back to justice.

Co vs. Barbers, 290 SCRA 717

Due Process in Extradition Proceedings

G.R. NO. 139465, January 8, 2000

SECRETARY OF JUSTICE V. JUDGE LANTION

Parties of the case:

Petitioners: Secretary of Justice

Respondents: Hon. Ralph C. Lantion, Presiding Judge, RTC of

Manila, Branch 25, and Mark B. Jimenez

Facts: On January 13, 1977, then President Marcos issued PD

No. 1069 Prescribing the Procedure for the Extradition of

Persons who has committed crimes in a Foreign Country. The

decree is founded on the doctrine of incorporation under the

Constitution.

On November 13, 1977, then Secretary of Justice Franklin

Drilon, representing the Philippines, signed in Manila the

Extradition treaty between the Philippines and the United

States of America (RP-US Extradition Treaty).

On November 13, 1944, the Department of Justice

received from the Department of Foreign Affairs U.S Note

Verbale No. 0522 containing as request for the extradition of

private respondent Mark Jimenez to the U.S. Mr. Jimenez

committed five (5) violations against the provisions of the

United States Code (USC). When the panel of attorneys began

with the technical evaluation and assessment of the extradition