Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Diagnostic Accuracy of Transvaginal Ultrasound For Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Bowel Endometriosis

Hochgeladen von

Lina E. ArangoOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Diagnostic Accuracy of Transvaginal Ultrasound For Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Bowel Endometriosis

Hochgeladen von

Lina E. ArangoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257263

Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/uog.8858

Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for

non-invasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic

review and meta-analysis

G. HUDELIST*, J. ENGLISH, A. E. THOMAS, A. TINELLI, C. F. SINGER**

and J. KECKSTEIN

*Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Clinic, Wilhelminen Hospital, Vienna, Austria; SEF, Stiftung

Endometrioseforschung; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Brighton Medical School, Brighton, UK; Department

of Methodological Research and Statistics, Institute of Psychology, Alpe Adria University Klagenfurt, Klagenfurt, Austria; Department of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Lecce Hospital, Lecce, Italy; **Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Vienna, Vienna,

Austria; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Center for Endometriosis, Villach Hospital, Villach, Austria

K E Y W O R D S: deep infiltrating endometriosis; presurgical diagnosis; transvaginal ultrasound

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Objective To critically analyze the diagnostic value

of transvaginal sonography (TVS) for non-invasive,

presurgical detection of bowel endometriosis.

Over the past decade, the use of transvaginal sonography (TVS) has improved the quality of non-invasive

assessment of patients with suspected pelvic pathologies.

With respect to endometriosis TVS has been shown

to be a highly sensitive tool for the detection of

ovarian endometriomas1 and is far superior to routine

clinical examination alone2,3 . Moore et al.1 systematically

reviewed 67 papers on the validity of TVS for the detection

of pelvic endometriosis, out of which seven fulfilled

the inclusion criteria and focused on TVS imaging of

ovarian endometriomas. The prevalence of the condition

ranged between 13 and 38%. Sensitivities, specificities and

positive (LR+) and negative likelihood ratios (LR) in six

studies using gray-scale ultrasonography ranged between

64 and 89%, 89 and 100%, 7.6 and 29.8 and 0.1 and 0.4,

respectively. The authors therefore concluded that TVS

should be regarded as a useful test for identifying cystic

ovarian endometriosis presurgically.

Recent studies also suggest that TVS could be an

accurate method for the detection of endometriosis in

extra-ovarian locations, i.e. uterosacral ligament involvement, endometriosis of the rectovaginal space, the pouch

of Douglas, the vagina, the urinary bladder and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) of the rectosigmoid3 8 . Since

TVS is a readily available, cost- and time-effective diagnostic instrument when compared to other radiological

procedures such as computed tomography and magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI)9,10 , several investigators have

further examined the diagnostic value of TVS for the noninvasive detection of DIE infiltrating the bowel. The aim

Methods MEDLINE (19662010) and EMBASE (1980

2010) databases were searched for relevant studies investigating the diagnostic accuracy of TVS for diagnosing deep

infiltrating endometriosis involving the bowel. Diagnosis

was established by laparoscopy and/or histopathological analysis. Likelihood ratios (LRs) were recalculated in

addition to traditional measures of effectiveness.

Results Out of 188 papers, a total of 10 studies fulfilled

predefined inclusion criteria involving 1106 patients

with suspected endometriosis. The prevalence of bowel

endometriosis varied from 24 to 73.3%. LR+ ranged from

4.8 to 48.56 and LR ranged from 0.02 to 0.36, with wide

confidence intervals. Pooled estimates of sensitivities and

specificities were 91 and 98%; LR+ and LR were 30.36

and 0.09; and positive and negative predictive values were

98 and 95%, respectively. Three of the studies used bowel

preparations to enhance the visibility of the rectal wall;

one study directly compared the use of water contrast vs.

no prior bowel enema, for which the LR was 0.04 and

0.47, respectively.

Conclusions TVS with or without the use of prior

bowel preparation is an accurate test for non-invasive,

presurgical detection of deep infiltrating endometriosis of

the rectosigmoid. Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published

by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Correspondence to: Prof. G. Hudelist, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Clinic, Wilhelminen

General Hospital, Montlearstrasse 37, A-1160 Vienna, Austria (e-mail: gernot hudelist@yahoo.de)

Accepted: 7 October 2010

Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Hudelist et al.

258

of this work was to systematically analyze the published

literature evaluating the role of TVS for the detection of

DIE involving the rectosigmoid.

METHODS

The MEDLINE (19662010) and EMBASE (19802010)

databases were searched using the following search

strategy:

1. (pelvic or ovarian or deep infiltrating) near2 (mass or

cyst* or tumo* r)

2. ENDOMETRIOSIS in MeSH or 1 or BOWEL

ENDOMETRIOSIS

3. 2, not case reports, not review articles

4. with checktags female and human

5. with ULTRASOUND/all subheadings or TRANSVAGINAL/all subheadings or SONOGRAPHY

Abstracts of all studies identified were read and

manuscripts were then fully reviewed. In addition,

reference lists of all reviewed manuscripts were searched

for additional data. Study selection and assessment of

quality were performed independently by two reviewers

(G. H. and J. E).

Selection criteria

All studies included in the present review had to be

prospective and were required to involve both TVS examination and surgical exploration of the pelvis either

by laparoscopy or by laparotomy (as stated by Moore

et al.1 ). Scientific publications including case reports, studies on adenomyosis or extrapelvic endometriotic disease

as well as retrospective case series and review articles

were excluded. Studies reporting on pregnant women,

rectal ultrasound as the only examination and endoscopic

sonography were also excluded from this review. Patients

included in the studies presented with either subfertility

or symptoms suggestive of endometriosis.

According to the criteria of Moore et al.1 , studies were

considered to be of good quality when information on

recruitment of patients, blinding of ultrasound operators

and surgeons and data on the technical equipment were

provided. In order to define the stage and severity of

disease (i.e. the final endpoint of diagnosis), studies had

to describe the anatomical location of deep infiltrating

disease combined with histological confirmation of

endometriosis. Moore et al.1 considered that studies

missing one or two of these criteria were of moderate/poor

quality.

Data extraction and presentation of results

As described by Moore et al.1 , 2 2 tables were created to

validate test results against surgical and histopathological

findings aimed at defining whether DIE involving the

rectosigmoid can be detected by TVS. In addition,

QUADAS (quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy of

Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

studies) was used to assess the studies11 . As described

previously, study quality is defined as high when 9

items out of 14 are met, moderate when 6 items are

met and low when < 6 criteria are met12 . LR+, LR

and test accuracy were calculated in studies lacking

these data. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated

as described previously1 using CATMaker statistical

software (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Oxford,

UK). In two cases raw data (true and false positive

and negative rates) were obtained from the authors.

Since heterogeneity is a common finding in diagnostic

meta-analyses we calculated Cochrans Q and I2 for

all measures to assess the significance and magnitude

of study heterogeneity13 . A forest plot was used to

assess eventual outlier studies (data not shown). Potential

sources of heterogeneity were explored by random-effects

meta-regression. Number of subjects, year of publication,

QUADAS scores and prevalence were used as study-level

covariates that predicted the logarithm of diagnostic odds

ratios (DORs). The studies were weighted by the inverse of

variance of the DOR to consider the precision with which

each study measured it. Relative DORs were calculated to

compare the overall DOR with the adjusted DOR. When

heterogeneity between studies is present, a random-effects

model can be used to obtain pooled estimates14 .

We applied random-effects models with the DerSirmonianLaird estimator in order to determine overall

estimates of sensitivity, specificity, LR+, LR and DOR.

For data with zero counts a continuity correction of 0.5

was added to every value in that study, thereby allowing

the calculation of all LRs15 . For the assessment of publication bias Eggers test and Beggs test were conducted

and funnel plots were investigated (data not shown). The

tests for publication bias and funnel plots were performed

with R statistical software version 2.11.1 metafor package (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria)16 . All

other analyses were performed with MetaDiSc statistical

software version 1.417 (Hospital Universitario, Madrid,

Spain).

RESULTS

The initial implementation of the research strategy

revealed 188 studies relating to endometriosis and/or

adenomyosis and/or ovarian endometriosis diagnosed

by laparoscopy or laparotomy and/or ultrasonography.

Out of these only 51 papers specifically used TVS

and surgical exploration to diagnose DIE. Of these 51

papers, seven were excluded because they were case

reports or descriptive in nature. A further 18 papers

did not meet the inclusion criteria due to the fact

that they were review articles, despite the exclusion

of this article type in the primary search process.

Finally, three other publications included comments on

publications and were also excluded from the final

analysis, leaving 23 manuscripts for review3 5,7,8,18 35 .

Out of these 23 papers, 13 publications were excluded

due to methodological problems; three papers were

purely retrospective in nature18,27,28 ; four manuscripts

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257263.

Transvaginal ultrasound in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis

were excluded because they involved a group of

patients already described in a previous publication

by the same group of authors5,7,25,29 and another

four papers were not included in the analysis because

insufficient information was provided on the presence

or absence of bowel endometriosis within the group of

women with endometriosis22,30,32,34 . Two papers were

excluded due to the low number of cases with proven

bowel endometriosis24 or insufficient information on the

anatomical localization of DIE affecting the bowel35 . Thus

10 papers fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included

in the final review. In addition to the quality criteria

described by Moore et al.1 , the QUADAS scores were

calculated for each of the studies. These ranged from 7 to

13, reflecting high methodological quality in eight cases

and moderate quality in two cases.

Out of these, four papers evaluated the diagnostic

value of TVS for the detection of DIE infiltrating the

rectosigmoid excluding other possible locations of DIE in

the analysis8,23,31,33 . All other works also evaluated the

potential of TVS for the visualization of other affected

sites of deep infiltrating disease such as the vagina,

rectovaginal space, uterosacral ligaments, bladder and

pouch of Douglas. Two papers addressed the use of

TVS to diagnose DIE involving the rectum, pouch of

Douglas, vagina, rectovaginal space, uterosacral ligaments

and bladder3,26 using laparoscopic exploration and

histological confirmation of endometriosis as the gold

standard test. One work compared TVS with MRI to

detect DIE preoperatively compared to the gold standard

laparoscopy without histological confirmation21 . One

paper assessed the diagnostic value of TVS vs. rectal

endosonography19 ; two papers compared TVS with MRI,

digital examination4 and rectal endosonography20 to

detect DIE presurgically. Data on the quality of these

studies including number of patients and cases of bowel

endometriosis, recruitment criteria, blinding, information

and presence of diagnostic criteria and technical details,

data on reference standards and assessment of the

grade of study quality are provided in Table 1. Table 2

depicts prevalence rates, sensitivities, specificities, test

accuracies, positive predictive values (PPVs), negative

predictive values (NPVs) and positive and negative LRs

with CIs of all studies included in the final analysis. The

number of patients with proven DIE infiltrating the bowel

undergoing preoperative TVS ranged from 1721 to 8123 .

Sensitivity and specificity varied from 67 to 98% and 92

to 100%, respectively.

As further demonstrated in Table 2, PPVs and NPVs

ranged from 87 to 100% and 75 to 99%, respectively.

LR+ goes up to infinity in cases lacking false-positive

findings and thus are not shown. LR+ of the remaining

studies varied from 4.8 to 48.56 and LR from 0.02 to

0.36.

Three studies used TVS combined with a bowel enema

to provide a better visualization of rectal wall anatomy,

specifically muscularis propria4,23,33 . Valenzano Menada

et al.33 directly compared whether adding water-contrast

in the rectosigmoid (RWC-TVS) during TVS improves

Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

259

presurgical diagnosis of rectal DIE with TVS. The

sensitivity of RWC-TVS vs. TVS in identifying rectal DIE

was 97 vs. 56%, the specificity 100 vs. 92.5%, the PPV

100 vs. 72% and the NPV 99 vs. 86%. Due to the absence

of false-positive cases in the RWC-TVS cohort, LR+ could

not be calculated, and LR was 0.04 vs. 0.47 for TVS.

Meta-analysis of all studies included in the final review

yielded significant results of Cochrans Q for all measures

except LR+ (sensitivity: P < 0.001, Q = 238.64, df =

9, I2 = 76.7%; specificity: P = 0.037, Q = 17.8, df =

9, I2 = 49.5%; LR+: P = 0.144, Q = 13.4, df = 9,

I2 = 33.0%; LR: P < 0.001, Q = 52.6, df = 9, I2 =

82.9%; DOR: P = 0.001, Q = 27.6, df = 9, I2 = 67.4%),

indicating considerable heterogeneity between studies.

Significant values for study heterogeneity were mainly

caused by two studies21,26 that were aberrant in respect

to sensitivity, LR and DOR. However, meta-regression

including sample size, prevalence, QUADAS and year of

publication did not yield any significant results: number

of subjects (P = 0.197, relative DOR = 1.02 (95% CI,

0.991.04)), prevalence (P = 0.568, relative DOR =

0.97 (95% CI, 0.881.08)), QUADAS score (P = 0.319,

relative DOR = 1.44 (95% CI, 0.653.20)) and year

of publication (P = 0.298, relative DOR = 1.35 (95%

CI, 0.672.71)). This suggests that although there was

relevant heterogeneity between the studies, the influence

of the covariates was not systematic. To account for

heterogeneity we used a random-effects model to perform

pooled estimates and estimate the respective CIs (Table 3).

As all studies were conducted with women who suffered

from pain or infertility, the pooled prevalence of 47%

refers to women with specific symptoms.

Evaluation by both Eggers test (P = 0.221) and Beggs

test (P = 0.293) did not show evidence of publication

bias for logDOR. This result was confirmed by inspection

of the funnel plots, which were all symmetrical for the

investigated diagnostic measures (sensitivity, specificity,

PPV, NPV, LR+, LR and accuracy; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis infiltrating the rectosigmoid can be

suspected in up to 922% of all women with proven

endometriosis36,37 . Symptoms of DIE involving the bowel

vary greatly, ranging from asymptomatic women with

extensive rectal involvement to patients with severe

dysmenorrhea and dyschezia38 . Treatment strategies

include hormonal preparations or surgical excision of

endometriotic nodules37,39 , but presurgical staging of

DIE is crucial for planning surgical treatment options.

The findings of our systematic review clearly suggest

that TVS is a highly valuable tool for the non-invasive

detection of DIE affecting the rectosigmoid. In addition to

sensitivities, specificities, PPVs, NPVs and test accuracies,

we recalculated all positive and negative LRs since these

reflect the diagnostic accuracy and the clinical usefulness

of a test independently of the prevalence of the study

condition in the study population1 . The prevalence of

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257263.

Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Sonographer

blinded

Sonographers

blinded

No information

given

Sonographer

blinded

Radiologists

blinded

Sonographer not

blinded to PV

Sonographer

blinded

Prospective

Prospective

Prospective

Prospective

Prospective

Prospective

Prospective

Prospective

Not described

Yes; nodular, predominantly

solid, hypoechogenic lesion

adhered to the wall of the

intestinal loop

Yes; rectovaginal hypoechoic

mass adherent and/or

penetrated into the

intestinal wall thickening

the muscularis mucosa

Yes; presence of some thin

band-like echoes departing

from the center of the mass

as an Indian head dress.

Yes; irregular hypoechoic

mass, with or without

hypo/hyperechoic foci

involving colon muscularis

Yes; as above

Yes; as above

Yes; long, nodular,

predominantly solid,

hypoechogenic lesion

adhered to the wall of the

intestinal loop

Sonographer

blinded

Not stated

Prospective

Sonographers

blinded

Yes; thickening of the

muscularis propria > 3 mm,

which is hypoechoic and

thin (< 3 mm) under

normal circumstances

Yes; as above

Prospective

Study design Blinding

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Consecutive; pain

and infertility

Recruitment;

cause for referral

194

200

92

134

88

90

104

32

142

30

81

48

63

75

39

23

54

17

47

22

Laparoscopic

visualization

Histology

Histology in 29

Histology

Reference

standard

TVS

TVS, MRI,

PV, RES

TVS, PV

TVS

TVS

Histology

Histology

Histology in 54

Histology

Histology

TVS,

Histology

RWC-TVS

TVS, MRI,

PV

TVS, MRI

TVS

TVS, RES

Patients with

Cases of

suspected

rectal/sigmoidal

endometriosis endometriosis Test

( n)

( n)

method

Good (12)

Moderate (13)

Good (12)

Good (12)

Good (11)

Good (12)

Moderate (10)

Poor (7)

Moderate (8)

Moderate (9)

Study quality

according to

Moore criteria

(QUADAS score)

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PV, per vaginam clinical examination; QUADAS, quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy of studies; RES, rectal endosonography; RWC, rectal water contrast;

TVS, transvaginal sonography.

Bazot et al.

(2009)20

Hudelist et al.

(2009)8

Goncalves et al.

(2010)23

Piketty et al.

(2009)31

Guerriero et al.

(2008)26

Valenzano

Menada et al.

(2008)33

Bazot et al.

(2004)3

Carbognin et al.

(2006)21

Abrao et al.

(2007)4

Bazot et al.

(2003)19

Study

Diagnostic criteria stated;

ultrasound criteria for

diagnosis

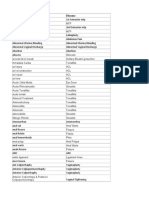

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies included in the analysis

260

Hudelist et al.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257263.

261

0.05 (0.010.31)

0.13 (0.060.28)

0.29 (0.140.61)

0.02 (0.000.13)

0.04 (0.010.3)

0.36 (0.230.57)

0.10 (0.050.20)

0.06 (0.020.16)

0.04 (0.010.17)

0.02 (0.010.10)

Table 3 Overall analysis of all studies included in the final analysis

using a random-effects model to perform pooled estimates of

variables

Variable

27.62 (9.0284.58)

4.8 (1.2618.31)

8.17 (3.1121.44)

26.29 (6.72102.83)

48.56 (15.81149.10)

Sensitivity (%)

Specificity (%)

LR+

LR

DOR

Prevalence (%)

PPV (%)

NPV (%)

Estimate (95% CI)

91 (88.193.5)

98 (96.799.0)

30.36 (15.45759.626)

0.09 (0.0460.188)

394.3 (116.31336.0)

47 (36.757.3)

98 (96.799.6)

95 (92.197.7)

DOR, diagnostic odds ratio (values not adjusted); LR+, positive

likelihood ratio (with continuity correction for studies with

null-cells); LR, negative likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive

value; PPV, positive predictive value.

LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR, negative likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

97

94

84

99

99

81

93

96

98

99

89

94

75

98

99

78

89

88

99

98

100

93

100

100

100

87

97

100

94

100

8/8 (100)

92/95 (97)

15/15 (100)

50/50 (100)

67/67 (100)

45/49 (92)

56/58 (97)

29/29 (100)

149/152 (98)

113/113 (100)

21/22 (95)

41/47 (87)

12/17 (71)

53/54 (98)

22/23 (96)

26/39 (67)

68/75 (91)

59/63 (94)

46/48 (96)

79/81 (98)

22/30 (73)

47/142 (33)

17/32 (53)

54/104 (52)

23/90 (26)

39/88 (44)

75/133 (56)

63/92 (68)

48/200 (24)

81/194 (42)

Bazot et al. (2003)19

Bazot et al. (2004)3

Carbognin et al. (2006)21

Abrao et al. (2007)4

Valenzano Menada et al. (2008)33

Guerriero et al. (2008)26

Piketty et al. (2009)31

Bazot et al. (2009)20

Hudelist et al. (2009)8

Goncalves et al. (2010)23

Study

Prevalence of

rectal/sigmoidal

endometriosis

(n (%))

Table 2 Analysis of data in the included studies

Sensitivity

(n (%))

Specificity

(n (%))

PPV (%)

NPV (%)

Accuracy (%)

LR+ (95% CI)

LR (95% CI)

Transvaginal ultrasound in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis

Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

DIE involving the bowel ranged from 24 to 73%, which

may be attributable to different referral patterns and the

availability of tertiary referral centers providing sufficient

expertise in the presurgical diagnosis and treatment of

rectal DIE. LR+ ranged from 4.821 to 27.623 and LR

from 0.0223 to 0.3626 . The combined use of TVS with

vaginal examination may further increase the diagnostic

accuracy, with reported LR+ and LR 48.56 and 0.048 ,

respectively. In addition, it should be noted that LR+

went up to infinity in five studies (Table 2), suggesting

highly accurate presurgical test results.

Performance of a meta-analysis of all included studies

by using a random-effects model to calculate pooled

estimates revealed LR+ and LR of 30.36 and 0.09,

respectively. According to Altman40 , a very helpful test

for establishing or excluding a condition is characterized

by an LR+ > 10 and an LR < 0.1, while a test is

regarded as moderately helpful with an LR+ between 5

and 10 and an LR between 0.1 and 0.2. As depicted in

Table 3, the results of our meta-analysis clearly suggest

that TVS is indeed very useful for sonographic diagnosis

but also presurgical exclusion of bowel endometriosis.

Two studies21,26 were aberrant with respect to sensitivity,

LR and DOR. This may be attributable to low sensitivity

values in association with small patient numbers21 or

the use of tenderness guided transvaginal sonography26 ,

which may be less sensitive in cases of endometriotic

involvement of the upper rectum/lower sigmoid, since

these locations may not appear as painful sites when

using this technique.

The conclusions of this review are weakened by the

fact that blinding of the surgeon was missing in all

studies included in the final analysis, which might have

a potential influence on the results of the gold standard

test, i.e. surgery. On the other hand, information on

the preoperative findings is essential for guiding the

surgical technique and surgical diagnosis of endometriosis

in everyday clinical practice.

An additional variable in the accuracy of the gold

standard test, i.e. laparoscopy, is the fact that several

studies did not provide sufficient information about the

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257263.

262

surgical exploration of the patients with DIE3,20,21,26

since complete cul-de-sac obliteration secondary to

endometriosis was reported but could not necessarily

be surgically cleared. This may, in cases of DIE

affecting the non-visible, occluded lower rectum, lead

to misinterpretation and observation bias of the gold

standard test and consequently negatively affect the

validation of the index test, i.e. TVS. Hence, full surgical

exploration of patients with an occluded pouch of Douglas

is important for the final and accurate diagnosis of

bowel endometriosis since DIE may be missed at the

time of laparoscopy, thereby questioning the quality

of laparoscopic visualization of the pelvis as the gold

standard test for the diagnosis of endometriosis.

Another limiting factor to the results of this systematic

review is the heterogeneity of populations included in

the studies. Some authors failed to provide sufficient

data on the selection criteria and referral patterns of

centers where studies were conducted. Due to the fact

that most patients were treated in tertiary referral centers,

it is conceivable that the study populations represent an

already preselected patient cohort with a high prevalence

of bowel endometriosis. As a consequence, the conclusions

of this review may therefore only be applicable to a tertiary

referral setting and patients with a high risk for DIE.

In clinical everyday practice, exclusion of DIE is of

critical importance since extensive bowel involvement

warrants an interdisciplinary approach and referral to

a tertiary center. In conclusion, the majority of the

published evidence suggests that TVS is a highly useful

and easy accessible test for the preoperative detection of

DIE infiltrating the rectosigmoid. Whether the widespread

use of TVS and the inclusion of TVS in specialist training

programs lead to a reduction in the diagnostic delay of

patients with endometriosis remains to be seen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank Dr Simone Ferrero and MMag

Nadja Fritzer for their support and helpful advice. This

work was supported by the OEGEO, Osterreichische

Endokrinologische Onkologie.

Gesellschaft fur

REFERENCES

1. Moore J, Copley S, Morris J, Lindsell D, Golding S, Kennedy S.

A systematic review of the accuracy of ultrasound in the

diagnosis of endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002;

20: 630634.

2. Nezhat C, Santolaya J, Nezhat FR. Comparison of transvaginal

sonography and bimanual pelvic examination in patients with

laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol

Laparosc 1994; 1: 127130.

3. Bazot M, Thomassin I, Hourani R, Cortez A, Darai E. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for deep pelvic

endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2004; 24: 180185.

4. Abrao MS, Goncalves MO, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Chamie LP,

Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the

diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2007; 22:

30923097.

Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Hudelist et al.

5. Bazot M, Malzy P, Cortez A, Roseau G, Amouyal P, Darai E.

Accuracy of transvaginal sonography and rectal endoscopic

sonography in the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 30: 9941001.

6. Hudelist G, Keckstein J. The use of transvaginal sonography

(TVS) for preoperative diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis. Praxis

(Bern 1994) 2009; 98: 603607.

7. Hudelist G, Oberwinkler KH, Singer CF, Tuttlies F, Rauter G,

Ritter O, Keckstein J. Combination of transvaginal sonography

and clinical examination for preoperative diagnosis of pelvic

endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2009; 24: 10181024.

8. Hudelist G, Tuttlies F, Rauter G, Pucher S, Keckstein J. Can

transvaginal sonography predict infiltration depth in patients

with deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum? Hum Reprod

2009; 24: 10121017.

9. Kinkel K, Frei KA, Balleyguier C, Chapron C. Diagnosis of

endometriosis with imaging: a review. Eur Radiol 2006; 16:

285298.

10. Brosens I, Puttemans P, Campo R, Gordts S, Kinkel K. Diagnosis of endometriosis: pelvic endoscopy and imaging techniques.

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2004; 18: 285303.

11. Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The

development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of

studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews.

BMC Med Res Methodol 2003; 3: 25.

12. Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic

accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2009; 201: 107.e16.

13. Sidik K, Jonkman JN. Simple heterogeneity variance estimation

in meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc [Ser C] 2005; 54: 367384.

14. Deville W, Buntix F, Bouter LM, Montori VM, de Vet HC, van

der Windt DA, Bezemer PD. Conductiong systematic reviews of

diagnostic studies: didactic guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol

2002; 2: 29.

15. Goodacre S, Sampson F, Thomas S, van Beek E, Sutton A.

Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy

of ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis. BMC Med

Imaging 2005; 5: 56.

16. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analysis in R with the

metaphor package. J Stat Softw 2010; 36: 148.

17. Zamora J, Abraira V, Muriel A, Khan K. Coomarasamy MetaDiSc: a software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC

Med Res Methodol 2006; 6: 612.

18. Balleyguier C, Chapron C, Dubuisson JB, Kinkel K, Fauconnier A, Vieira M, Helenon O, Menu Y. Comparison of magnetic

resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography in diagnosing bladder endometriosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc

2002; 9: 1523.

19. Bazot M, Detchev R, Cortez A, Amouyal P, Uzan S, Darai E.

Transvaginal sonography and rectal endoscopic sonography

for the assessment of pelvic endometriosis: a preliminary

comparison. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: 16861692.

20. Bazot M, Lafont C, Rouzier R, Roseau G, Thomassin-Naggara

I, Darai E. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination,

transvaginal sonography, rectal endoscopic sonography, and

magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose deep infiltrating

endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2009; 92: 18251833.

21. Carbognin G, Girardi V, Pinali L, Raffaelli R, Bergamini V,

Pozzi Mucelli R. Assessment of pelvic endometriosis: correlation

of US and MRI with laparoscopic findings. Radiol Med 2006;

111: 687701.

22. Eskenazi B, Warner M, Bonsignore L, Olive D, Samuels S,

Vercellini P. Validation study of nonsurgical diagnosis of

endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2001; 76: 929935.

23. Goncalves MO, Podgaec S, Dias JA Jr, Gonzalez M, Abrao MS.

Transvaginal ultrasonography with bowel preparation is able to

predict the number of lesions and rectosigmoid layers affected

in cases of deep endometriosis, defining surgical strategy. Hum

Reprod 2010; 25: 665671.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257263.

Transvaginal ultrasound in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis

24. Grasso RF, Di Giacomo V, Sedati P, Sizzi O, Florio G, Faiella E,

Rossetti A, Del Vescovo R, Zobel BB. Diagnosis of deep

infiltrating endometriosis: accuracy of magnetic resonance

imaging and transvaginal 3D ultrasonography. Abdom Imaging

2009; 35: 716725.

25. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Gerada M, DAquila M, Piras B, Melis

GB. Tenderness-guided transvaginal ultrasonography: a new

method for the detection of deep endometriosis in patients with

chronic pelvic pain. Fertil Steril 2007; 88: 12931297.

26. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Gerada M, Virgilio B, Angioni

S, Melis GB. Diagnostic value of transvaginal tendernessguided ultrasonography for the prediction of location of deep

endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2008; 23: 24522457.

27. Hensen JH, Puylaert JB. Endometriosis of the posterior culde-sac: clinical presentation and findings at transvaginal

ultrasound. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 192: 16181624.

28. Koga K, Osuga Y, Yano T, Momoeda M, Yoshino O, Hirota Y,

Kugu K, Nishii O, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y. Characteristic

images of deeply infiltrating rectosigmoid endometriosis on

transvaginal and transrectal ultrasonography. Hum Reprod

2003; 18: 13281333.

29. Menada MV, Remorgida V, Abbamonte LH, Fulcheri E, Ragni

N, Ferrero S. Transvaginal ultrasonography combined with

water-contrast in the rectum in the diagnosis of rectovaginal

endometriosis infiltrating the bowel. Fertil Steril 2008; 89:

699700.

30. Okaro E, Condous G, Khalid A, Timmerman D, Ameye L,

Huffel SV, Bourne T. The use of ultrasound-based soft markers

for the prediction of pelvic pathology in women with chronic

pelvic pain can we reduce the need for laparoscopy? BJOG

2006; 113: 251256.

31. Piketty M, Chopin N, Dousset B, Millischer-Bellaische AE,

Roseau G, Leconte M, Borghese B, Chapron C. Preoperative

work-up for patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis:

transvaginal ultrasonography must definitely be the first-line

imaging examination. Hum Reprod 2009; 24: 602607.

Copyright 2011 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

263

32. Savelli L, Manuzzi L, Pollastri P, Mabrouk M, Seracchioli R,

Venturoli S. Diagnostic accuracy and potential limitations of

transvaginal sonography for bladder endometriosis. Ultrasound

Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 595600.

33. Valenzano Menada M, Remorgida V, Abbamonte LH, Nicoletti A, Ragni N, Ferrero S. Does transvaginal ultrasonography

combined with water-contrast in the rectum aid in the diagnosis of rectovaginal endometriosis infiltrating the bowel? Hum

Reprod 2008; 23: 10691075.

34. Yazbek J, Helmy S, Ben-Nagi J, Holland T, Sawyer E, Jurkovic

D. Value of preoperative ultrasound examination in the selection

of women with adnexal masses for laparoscopic surgery.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 30: 883888.

35. Holland TK, Yazbek J, Cutner A, Saridogan E, Hoo WL,

Jurkovic D. Value of transvaginal ultrasound in assessing the

severity of pelvic endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2010; 36: 241248.

36. Chapron C, Chopin N, Borghese B, Foulot H, Dousset B,

Vacher-Lavenu MC, Vieira M, Hasan W, Bricou A. Deeply

infiltrating endometriosis: pathogenetic implications of the

anatomical distribution. Hum Reprod 2006; 21: 18391845.

37. Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Vieira M, Barakat H, Dousset B,

Pansini V, Vacher-Lavenu MC, Dubuisson JB. Anatomical distribution of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: surgical implications and proposition for a classification. Hum Reprod 2003;

18: 157161.

38. Ballard K, Lane H, Hudelist G, Banerjee S, Wright J. Can

specific pain symptoms help in the diagnosis of endometriosis?

A cohort study of women with chronic pelvic pain. Fertil Steril

2010; 94: 2027.

39. Keckstein J, Ulrich U, Kandolf O, Wiesinger H, Wustlich M.

Laparoscopic therapy of intestinal endometriosis and the

ranking of drug treatment. Zentralbl Gynakol 2003; 125:

259266.

40. Altman DG. Statistics in medical journals: developments in the

1980s. Stat Med 1991; 10: 18971913.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257263.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Obstetric Disorders IN THE UCI 2009 CHEST PDFDokument14 SeitenObstetric Disorders IN THE UCI 2009 CHEST PDFLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Anatomical Complications of Hysterectomy2017Dokument18 SeitenAnatomical Complications of Hysterectomy2017Lina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advances in Asthma in 2016 PDFDokument10 SeitenAdvances in Asthma in 2016 PDFLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Chiari I Malformation and Spontaneous HypotensionDokument4 SeitenChiari I Malformation and Spontaneous HypotensionLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Isuog Screening SNCDokument8 SeitenIsuog Screening SNCLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Advances in The SUI Surgeries 2017Dokument5 SeitenAdvances in The SUI Surgeries 2017Lina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Anemia in Pregnancy - ACOG 2008Dokument7 SeitenAnemia in Pregnancy - ACOG 2008Ernesto Ewertz Miquel100% (2)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- 5 Hysterectomy: R.D. ClaytonDokument15 Seiten5 Hysterectomy: R.D. ClaytonLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Medical Therapies For Uterine FibroidsDokument20 SeitenMedical Therapies For Uterine FibroidsLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Cuidado CriticoDokument8 SeitenCuidado CriticoLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- RS Impacto Incisiones PDFDokument10 SeitenRS Impacto Incisiones PDFLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Pathophysiology of Ischemic Placental Disease James M. Roberts MD [Investigator Magee-Womens Research Institute, Professor] Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Epidemiology and Clinical and Translational Research, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA 15213Dokument13 SeitenPathophysiology of Ischemic Placental Disease James M. Roberts MD [Investigator Magee-Womens Research Institute, Professor] Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Epidemiology and Clinical and Translational Research, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA 15213Lina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anomalias CromosomicasDokument12 SeitenAnomalias CromosomicasLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- ACOG Practice Bulletin - Asthma in PregnancyDokument8 SeitenACOG Practice Bulletin - Asthma in PregnancyEirna Syam Fitri IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Abdominal PainDokument15 SeitenAbdominal PainLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Embarazo MultipleDokument15 SeitenEmbarazo MultipleLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Nausea y Vomito en El EmbarazoDokument13 SeitenNausea y Vomito en El EmbarazoLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACOG Committee Opinion No 348 Umbilical Cord Blood Gas and Acid-Base AnalysisDokument4 SeitenACOG Committee Opinion No 348 Umbilical Cord Blood Gas and Acid-Base AnalysisLina E. Arango100% (1)

- A Review of The Management of Gallstone Disease and ItsDokument10 SeitenA Review of The Management of Gallstone Disease and ItsLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nausea y Vomito en El EmbarazoDokument13 SeitenNausea y Vomito en El EmbarazoLina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endometriosis Surgical Treatment of Endometrioma Sep 2012Dokument8 SeitenEndometriosis Surgical Treatment of Endometrioma Sep 2012Lina E. ArangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- HaemDokument15 SeitenHaemChairul Nurdin AzaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- OSCE Gynae-OSCE-MMSSDokument24 SeitenOSCE Gynae-OSCE-MMSSMohammad Saifullah100% (1)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology DepartmentDokument6 SeitenObstetrics and Gynecology Departmentabdelhamed aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Eng - Teste 2020-2021Dokument97 SeitenEng - Teste 2020-2021nistor97Noch keine Bewertungen

- ENDOMETRIOSISDokument33 SeitenENDOMETRIOSISSusi Indriastuti83% (6)

- Ovarian DisordersDokument5 SeitenOvarian DisordersNada MuchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ok Hi RekapDokument48 SeitenOk Hi RekapRafika Novianti CikovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Question Papers - Vol IIDokument19 SeitenObstetrics and Gynecology Question Papers - Vol IIprinceejNoch keine Bewertungen

- The TYWLS Times - June 2018 EditionDokument14 SeitenThe TYWLS Times - June 2018 EditionThe TYWLS TimesNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Miasmatic Approach To Endometriosis-1Dokument34 SeitenA Miasmatic Approach To Endometriosis-1Suriya OsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of Cabergoline Compared To Dienogest in Women With Symptomatic EndometriomaDokument6 SeitenThe Effects of Cabergoline Compared To Dienogest in Women With Symptomatic EndometriomaAnna ReznorNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Scientist International Edition - 27 January 2024Dokument52 SeitenNew Scientist International Edition - 27 January 20242mcommerceconsultingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endometriosis NEJM 2020 PDFDokument13 SeitenEndometriosis NEJM 2020 PDFluis medinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michelle - Proctor@corrections - Govt.nz Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility GroupDokument21 SeitenMichelle - Proctor@corrections - Govt.nz Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility GroupnarkeeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand Plan For Dienogest by Saqib AltafDokument13 SeitenBrand Plan For Dienogest by Saqib AltafSakib ZabooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual of Prototype Clinical Histories.: GeorgeDokument41 SeitenManual of Prototype Clinical Histories.: Georgemacdominic22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study On Endometriosis Treatment With Siddha MedicineDokument5 SeitenCase Study On Endometriosis Treatment With Siddha Medicinejuliet rubyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Differential Diagnosis of The Adnexal Mass 2020Dokument38 SeitenDifferential Diagnosis of The Adnexal Mass 2020Sonia MVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Cesarean Delivery: Postoperative Issues - UpToDateDokument12 SeitenCesarean Delivery: Postoperative Issues - UpToDateZurya UdayanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation By: Oka Chintyasari AldilaDokument37 SeitenPresentation By: Oka Chintyasari AldilaOka ChintyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Herbal Formularies For Health Professionals, Volume 3: Endocrinology, Including The Adrenal and Thyroid Systems, Metabolic Endocrinology, and The Reproductive Systems - Dr. Jill StansburyDokument5 SeitenHerbal Formularies For Health Professionals, Volume 3: Endocrinology, Including The Adrenal and Thyroid Systems, Metabolic Endocrinology, and The Reproductive Systems - Dr. Jill Stansburyjozutiso17% (6)

- Effectiveness of Manual Therapy On Chronic Pelvic PainDokument41 SeitenEffectiveness of Manual Therapy On Chronic Pelvic PainMuhammadRizalN100% (1)

- What Is DiseaseDokument19 SeitenWhat Is Diseaseparichaya1984Noch keine Bewertungen

- Obesity As Disruptor of The Female Fertility: Review Open AccessDokument13 SeitenObesity As Disruptor of The Female Fertility: Review Open Accessirfan dwiputra rNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maya Abominal MassageDokument1 SeiteMaya Abominal MassageMaureenManningNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dysmenorrhea Definition PDFDokument14 SeitenDysmenorrhea Definition PDFYogi HermawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gyne Past Papers Update 5Dokument139 SeitenGyne Past Papers Update 5Misbah KaleemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bee Propolis May Improve Fertility in Women With en Dome Trios IsDokument2 SeitenBee Propolis May Improve Fertility in Women With en Dome Trios Isapi-3723677Noch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1016@j Jmig 2019 10 024Dokument3 Seiten10 1016@j Jmig 2019 10 024houssein.hajj.mdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gyn & ObsDokument19 SeitenGyn & ObsAnonymous RxWzgONoch keine Bewertungen

- ResearchDokument33 SeitenResearchሌናፍ ኡሉምNoch keine Bewertungen

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeVon EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsVon EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (42)

![Pathophysiology of Ischemic Placental Disease James M. Roberts MD [Investigator Magee-Womens Research Institute, Professor] Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, Epidemiology and Clinical and Translational Research, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA 15213](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/275840982/149x198/9c5147ed3c/1440448978?v=1)