Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Sustainability, Evolution and Dissemination of Information and Communication Technology Supported Classroom Practice

Hochgeladen von

Jing WenOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Sustainability, Evolution and Dissemination of Information and Communication Technology Supported Classroom Practice

Hochgeladen von

Jing WenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233174403

Sustainability, evolution and

dissemination of information and

communication technology

supported classroom practice

ARTICLE in RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION MARCH 2007

Impact Factor: 0.51 DOI: 10.1080/02671520601152102

CITATIONS

READS

14

29

2 AUTHORS, INCLUDING:

Sara Hennessy

University of Cambridge

70 PUBLICATIONS 1,829 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Sara Hennessy

Retrieved on: 02 March 2016

Research Papers in Education

Vol. 22, No. 1, March 2007, pp. 6594

Sustainability, evolution and

dissemination of information and

communication technology-supported

classroom practice

Rosemary Deaney* and Sara Hennessy

University of Cambridge, UK

Research

10.1080/02671520601152102

RRED_A_215137.sgm

0267-1522

Original

Taylor

102007

22

rld29@cam.ac.uk

RosemaryDeaney

00000March

and

&

Article

Papers

Francis

(print)/1470-1146

Francis

2007

in Ltd

Education (online)

This study took place in a climate of an intensified focus on approaches to whole school improvement through embedding technology in teaching, learning and management. It examined the

evolution over time of classroom practice supported by information and communication technology

(ICT) and its wider implementation within and outside of subject departments. Three years earlier

a group of teachers in five secondary schools in England had participated in a collaborative

programme of ten small-scale research projects in which they developed a range of pedagogical

strategies involving use of ICT. These spanned six main Curriculum areas: English, classics, geography, history, science and technology, plus a language support group. The present study investigated the extent of development and dissemination of these practices over time, and identified the

underlying mechanisms and supportive or constraining factors. This follow-up study comprised an

interview survey of the 16 teachers and nine of their colleagues. Pedagogical approaches to using

new technologies proved to be robust over time, to be spreading from subject teachers to their

colleagues, and to be integrated into departmental schemes of work. However, findings indicated

that evolution of practice depends on adequate access to reliable resources, and development of

ICT as a school priority in turn leads to soliciting further resources and expanding practice.

Individual teachers confidence, skills and motivation towards using ICT to promote learning

develop in response to other contextual factors, most prominently a supportive organizational

culture and a collegial environment, and they play a critical role in the processes of developing and

disseminating new practice. These processes are thus complex and iterative.

Keywords: Classroom practice; England; Information technology; Learning communities;

Professional development; Secondary education

*Corresponding author. University of Cambridge Faculty of Education, 184 Hills Road,

Cambridge CB2 2PQ, UK. Email: rld29@cam.ac.uk

ISSN 0267-1522 (print)/ISSN 1470-1146 (online)/07/01006530

2007 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/02671520601152102

66 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

Introduction

Three years before this study, a group of 16 UK secondary teachers had participated

in a collaborative programme of ten small-scale research projects in which they developed a range of technology-integrated pedagogical strategies (TiPS) within their

subject areas. The teachers were supported by a university research team which

included the authors of this paper. The study reported here investigated whether and

how the teachers practices had moved forward over the three years, and what had

influenced these developments. It comprised a follow-up interview survey with the

original teachers plus nine of their colleagues.

The paper begins by describing the educational context of the study and relates the

research to previous work concerning practitioners developing use of ICT within the

classroom. Details of the earlier TiPS project and the research methods employed in

the follow-up study precede an account of the findings. The first two findings sections

report on the extent to which practices had both evolved and been disseminated and

the underlying mechanisms involved; the third section describes the factors that

appeared to have influenced these processes. A case study is then presented to

illustrate how particular factors and mechanisms came into play in one department,

and contrasts made with other cases. The interrelationships between mechanisms and

factors are discussed and a model suggested to show how these links may operate.

The paper concludes by outlining some implications for policy and practice.

Educational context

Over recent years, unprecedented Government investment in ICT in schools has

been directed at implementing infrastructure and connectivity. An exponential

increase in computer-based resources (including laptops for teachers and projection

technology: DfES, 2004) has ensued, and focus has now shifted towards whole school

improvement through utilization of the electronic systems and services that continue

to be put in place (DfES, 2003). However, the potentially transformative power of

technology so widely acclaimed within official rhetoric is not yet reflected in the reality of mainstream educational practice. Findings of a major national study, ImpaCT2

(Harrison et al., 2002), pointed towards the potential yields to be derived from

embedding ICT in all aspects of learning, teaching and management, but progress is

slow. Reports suggest that as few as 15% of all schools have so far incorporated ICT

in these ways across the whole school (Day, 2004).

In order to assist teachers to become competent users of the new technologies, 230

million pounds was made available in 1999 from the New Opportunities Fund

(NOF) to provide training programmes across the UK. Around 80% of eligible teachers completed the training, but feedback indicated that support at school level was key

to promoting classroom use of the new tools and more understanding of underlying

pedagogies was needed (Preston, 2004). Indeed, the continuing importance of

providing guidance on incorporating effective, subject-related pedagogy has been

widely acknowledged (see Cox et al., 2003; Ofsted, 2004) and is now emphasized in

ICT-supported classroom practice

67

the ICT in Schools initiative (DfES, 2003). The study reported here provides

unique qualitative information concerning teachers experiences of developing and

disseminating ICT-based practices during the recent period of intensified

Government focus on technology provision and training.

Integrating use of ICT into secondary school subject teaching

This project built on previous work in the area of integration of ICT use into subject

teaching. That research takes an evolutionary perspective on the processes of cultural

change. For example, Kerrs (1991) interviews and observations with American

teachers indicated that incorporating technology into their practice allowed obvious

and dramatic changes in classroom organization and management, yet changes in

teachers pedagogical thinking were slow and measured. Similarly, Nordkvelle and

Olson (2005) assert that teachers use ICT instrumentally in their practice to amplify

preferred, pre-existing instructional practices. Our previous interview and observational studies within TiPS project schools indicated that a gradual but perceptible

process of pedagogical evolution appears to be taking place (Hennessy et al., 2005b).

This involves both pupils and teachers developing new strategies and ways of thinking

in response to new experiences and the lifting of existing constraints.

This line of previous research has also highlighted the many factors which may have

an impact on teachers motivation to implement, continue to develop, or to share

innovative practice. Perceptions about the usefulness of ICT in aiding and extending

learning and challenging pupil thinking are influential (Cox, 2004), and the belief

that an innovation should offer added value above and beyond existing practice

(Hennessy et al., 2005b), is central here. New approaches must also be compatible

with existing pedagogy and be perceived as meeting a need. We might additionally

expect sustainable and transferable innovations to be user-friendly, adaptable and

applicable to other classroom contexts. Many studies have pointed to the practical

constraints operating within the working contexts in which teachers currently find

themselves. Indeed, Cuban (2001) suggests that the cellular classroom organization,

tight time scheduling and departmental boundaries that characterize secondary

schools, along with the demands of curricular coverage and assessment, may both

inhibit use of technology in classrooms and retard widespread changes in teaching

practices. Innovation and adaptation are costly in terms of time; developing effective

pedagogy around ICT involves significant input in terms of planning, preparation and

follow-up of lessons (Cox et al., 2003). Other contextual factors which can act as

barriers include: lack of confidence, experience, motivation, and training; access to

reliable resources; classroom practices which clash with the culture of student exploration, collaboration, debate and interactivity within which much technology-based

activity is said to be situated (Hadley & Sheingold, 1993; Becker, 2000; Dawes,

2001). Some writers distinguish between school level and teacher level barriers,

with teacher level factors such as pedagogical beliefs, technical skill and confidence

viewed as particularly influential (Mumtaz, 2000). Another literature review focusing

on barriers to using ICT highlighted the complex relationships between external or

68 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

first order influences such as access to reliable technology, and internal or second

order influences such as school culture, teacher beliefs and skills (Becta, 2003a).

Tearles recent work (2004) confirms that availability of resources and whole

school characteristics, culture and ethos are all highly influential. Similarly, in a

comprehensive review of literature concerned with factors that enable teachers to

make successful use of ICT, Scrimshaw (2004) cites the central role of school leadership and whole school strategic planning, but also notes how, at teacher level,

perceptions that link ICT with promotion of a student-centred pedagogy may in fact

deter some practitioners whose preference is for a more teacher-centred model.

Pedagogical adaption may thus represent a more difficult transition for many teachers

than the process of acquiring new technical skills (Fabry & Higgs, 1997). Dawes

(2001) describes how teachers develop professional expertise and the motivation to

evolve from being potential users (through the stages of participant, involved and

adept) to integral users ultimately; hence, potential obstacles may affect different

individuals and groups of colleagues to varying degrees.

Finally, secondary teachers in the UK do not generally work alone; the subject

department acts as a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991), sharing

resources, approaches, cultural values and aims, and collaboratively-developed

schemes of work. Our previous work leads us to expect departments which work

effectively together as teams to constitute robust communities of practice within

which innovations involving ICT may be readily shared (Ruthven et al., 2004).

However, research indicates that practice develops over time and this process is not

automatically triggered by simply sharing information with colleagues (Loveless et al.,

2001). It entails developing ideas and trying them out, considering the principles and

purposes that underpin activities in particular contexts, and critically reflecting on

them. Likewise, Hargreaves (1999) stresses the importance of professional tinkering

in the collaborative processes of knowledge creation. At the time of the TiPS project,

participating teachers spanned the spectrum of developing expertise but shared a

commitment to extending their practice in using ICT to support subject teaching.

They also worked within a supportive organizational culture, as evidenced by the

agreed agenda of schools within their research partnership to focus on developing use

of ICT. We were interested to see whether these apparently favourable conditions had

facilitated the dissemination of promising pedagogic approaches; independent

evidence about this from the relevant research coordinators was central here. We also

solicited the accounts of subject colleagues concerning their ways of working together

in order to understand the mechanisms underlying development of existing and new

pedagogical approaches to classroom use of ICT.

Research aims and focus

This project investigated the views and experiences of a group of teachers who had

already invested considerable time and research funds in a process of developing,

trialling and evaluating some new forms of technology-supported practice in their

own classroom settings. It examined a further stage in that process, namely the

ICT-supported classroom practice

69

subsequent evolution and dissemination of practice to colleagues. The first aim was

to evaluate the extent to which ICT-supported practices initiated by individual teachers or collaborative pairs were sustained and/or developed over time. Secondly, the

study assessed the actual and potential extent of dissemination of ICT-supported practices within or outside their subject department, via additional interviews with the

relevant colleagues. The third aim was to identify the key influences and constraints

upon teachers in sustaining, extending and disseminating innovative uses of ICT to

support subject teaching and learning.

Our central research questions were as follows:

Which practices were still in evidence three years later, had they been further

developed by the originator, and had they spread more widely?

What were the motivational and organizational factors of influence? In particular,

were the sustained practices considered to be particularly successful in terms of

pupils learning?

Were there any obstacles to sustaining or disseminating practice and had they been

overcome? Were any emerging organizational constraints school-based or departmental?

Additionally we were interested in between-school differences in ICT ethos, and

these were investigated via contrasting a case study of one English department with

practice in other contexts.

Background

The TiPS Project

The Technology-integrated Pedagogical Strategies Project was the main phase of a

wider research project concerned with analysing, developing, refining and documenting effective pedagogy for using ICT in subject teaching. It took place during the

school year 20002001 in the context of a research partnership between

the University of Cambridge Faculty of Education and state secondary schools in the

local area. All of the schools had identified the use of ICT to support subject teaching

and learning as a common priority for development.

Teachers participating in the TiPS project came from five of the partnership

schools and were funded mainly by the DfES Best Practice Research Scholarship

(BPRS) scheme. They were all researching and developing strategies incorporating

ICT within their own classroom practice and were represented by a colleague in each

school, acting as local research coordinator for the partnership programme. Details of

individual projects are provided in Table 1.

The university research team provided research support and feedback as well as

observing lessons on two occasions whilst case studies were underway. A cross-case

analysis of data derived from lesson observations, follow-up interviews and teachers

written research reports focused on two main aspects: teachers practical theories

about the contribution of ICT to teaching and learning (Ruthven et al., 2004; Deaney

70 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

Table 1.

School/

research

coordinator

Teacher

Colleague

Subject

Focus of TiPS project

Year

RG

History

Yr 9

Classics

RU

None

interviewed

ZA

Use of the Internet and other

resources to support project work on

the First World War

Developing search skills through

Internet research about Roman Life

Use of computer-based activities in

after-school club eg email, use of

DTP for compilation of recipe book

OT**

FE

Science

Use of the Internet to study the solar

system

Use of the Internet to study

ecosystems

Use of a technical design/drawing

package to support teaching of

orthographic projection

Yr 9

Use of text formatting tools to

support identification of poetic

techniques, textual form and

structure

Use of simulation software to

support teaching and learning of

electronic theory

Yr 8

Computer-based work on the theme

of homelessness and study of

Macbeth

Use of computer based resources to

support study of rivers and flooding

Yr 9

Use of DTP and web-authoring

packages to support re-versioning of

material on vampires for a Yr 7

audience

Yr 13

Use of word processing and

presentation software to support

production of Internet-based

material on vampires

Yr 7

Community AY

college

OL

(CC)/OL

LL*

Media

college

(MC)/QN

Sports

college

(SC)/LR

Technology

college

(TC)/SI

Village

college

(VC)/BI

Details of participants and their original TiPS Projects

EAL

VM

JN

MV

GR

Design

technology

LR

RE

BR

English

KE

AK

Design

technology

AI

SI

English

DR**

None

interviewed

Geography

YL

JI

Teachers

acted as

colleagues

to each

other

English

RA

Notes: * Interviewed whilst on secondment; ** interviewed, but had moved schools since TiPS Project.

Yr 10

Yr 12

Yr 9

Yr 10

Yr 8

ICT-supported classroom practice

71

et al., 2006) and the strategies teachers used to mediate the use of these technologies

within the classroom (Hennessy et al., 2005a; Ruthven et al., 2005).

At the time of the TiPS project, three of the five schools involved had specialist

statusarts and media, sports, and technology respectively; one of these was also a

beacon school. All were mixed-sex, non-selective schools and two included sixth

forms. By the standard benchmarks of free school meal entitlement and percentage

of higher GCSE passes, all but one of the schools were relatively socially advantaged

and all were relatively academically successful though only one was in the upper quartile range for this indicator.1 There was, however, considerable variation in ICT

provisionthe technology and media colleges being markedly better resourced than

the others, where inspection reports showed that limited access to ICT facilities

restricted development and use of ICT by subject departments. Since that time, ICT

provision has increased across all schools, notably in one school (SC) which has also

achieved leading edge status. A further school (CC) has been awarded specialist

(technology) status.

Follow-up

Three years had elapsed between the TiPS project and the follow-up study undertaken in 20032004. It was anticipated that some of the original 19 TiPS teacher

researchers would have left their posts during the intervening time and it transpired

that five were no longer working within the schools where they undertook their case

studies. Of those, two had taken up more senior appointments in other local schools

and another teacher was on secondment to the University Faculty of Education.

These three were included in the interview sample. Two teachers had moved away

from the area and these cases were not pursued. Of the 17 teachers we approached,

only one declined to be interviewed due to time pressure from other commitments.

All of the teacherresearchers who participated in the TiPS project were

established practitioners, motivated towards ICT use, who had volunteered to

develop their classroom practice in this area and were keen to apply research-based

approaches to their work. However their prior experience of using ICT varied

considerably. Ten of the 19 teachers had subsequently been promoted to management positions, either within their school or elsewhere and seven had continued

classroom research activities with funding from the BPRS scheme.

Research design and procedure

Participants

The participant sample for the TiPS follow-up interview study comprised three

groups: 16 of the original teacherresearchers, six of their nominated colleagues, and

the five research coordinators (two of whom were also TiPS teacherresearchers).

Cover funds were offered in each case to facilitate participation in interviews. In five

of the six cases where teachers had undertaken joint projects within their

72 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

departments, we interviewed them together (in pairs or, in one case, as a group of

three). In the remaining case, one of the two teachers concerned had moved away

from the area, so no joint interview was possible.

At the end of their interview, each teacher, or pair of teachers, was asked to nominate an appropriate colleague (such as the head of department, or another colleague

within or outside the subject department) who had used the approach or materials

that were developed during the TiPS project; it was important that this colleague was

able to comment on take-up within or beyond the department and/or shed light on

any organizational constraints experienced. In two cases, namely where teachers had

moved school or were on secondment, it was deemed inappropriate to seek colleague

corroboration. In a third case, the three teachers interviewed together acted as

colleagues to each other. Interviews were also arranged with each of the five research

coordinators in order to gain a wider view on the impact of TiPS projects within each

school.

In total, ten teacher interviews (five individual and five joint), six colleague interviews and five research coordinator interviews were carried out; 21 interviews in all.

In two cases, teachers were interviewed twice: once in their role as research coordinator, and once as classroom practitioner.

Interviews

Our survey was conducted through a series of semi-structured interviews so as to

explore in depth and face to face the salient issues underpinning our research questions. We devised and piloted three separate schedules for teachers (both individual

and pair/group interviews), colleagues and research coordinators, though there was

some overlap since all were asked about development and dissemination (teachers

only were asked about sustained practice). The colleague interviews were intended to

improve reliability of the data by providing corroboration for wider development of

the ICT-supported practice as a result of formal or informal dissemination, or, as

applicable, about any obstacles to this process. Similarly, research coordinators were

asked to describe any whole school or departmental organizational changes and/or

initiatives that had taken place within the last three years. They commented on

whether, and how, these had affected the use of ICT generally within the school, and

the further development and dissemination of ICT-supported teaching and learning

strategies. Where available, documentary evidence of sustained, disseminated and

evolving practice (e.g., worksheets and other materials) was also obtained.

Cross-case analysis

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were segmented into relatively short units of talk and imported into a computer database (QSR NUD*IST, a

dedicated qualitative data analysis package). The initial coding framework was

centred around three main (but interconnected) themes relating to how the ICTbased practices had been sustained, developed and disseminated. A provisional,

ICT-supported classroom practice

73

detailed coding framework was then developed through a process of constant recursive comparison (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). It focused on teacher interviews in the

first instance and was then refined to incorporate new codes needed to capture

themes arising from scrutiny of colleague and coordinator interview data. The

prototypical categories employed in vivo codes (Strauss, 1987) using the participants own language to describe codes wherever possible, for example: technology

access; technical confidence. Through further iterative review, categories were

organized into wider, analytic themes such as organizational factors and motivational factors for final coding of all of the transcripts and interrogation of data

within and across schools. Note that coding was restricted to classroom uses of ICT

rather than including administrative purposes. All coding was checked by both

researchers.

The cross-case analysis incorporated two distinct strands:

1. Sustainability and development of practice.

2. Disseminationincluding the extent of, and mechanisms associated with, these

processesplus the supporting or constraining factors across both strands.

In each case teacher data were compared with colleague and researchcoordinator

data, focusing on corroborative, elaborative and counter-examples.

Findings are outlined in the following sections. A case study of one English project

is then presented which illustrates the processes of evolution and dissemination of

practice within one department in more detail, drawing contrasts with other cases.

Strand 1 findings: sustainability and development of TiPS practice

Extent of sustained use and development over time

All of the participating teachers were found to have sustained and further developed the

particular approaches and practices they had initiated three years previously, and to

be using technology in other ways as well. In seven cases, minor modifications or refinements had been made, for example instigating more focused Internet research activity

in Science. In eight cases, the practice had been developed in new or substantial ways,

for instance the introduction of electronic writing frames in English which allowed the

teacher to exemplify effective writing practice and to comment unobtrusively on pupil

work in progress.

Most teachers perceived considerable potential for further development of their

practices, either in ways which they could imagine themselves (mainly) or in ways

which colleagues had developed. In five cases, anticipated increases in technology

resources or speculation about how new technology might be used underpinned the

perceived potential:

This other lad in the department hes virtually always got the projector set up and is

using it to show just one thing, maybe from the Internet, how populations changing

Ive done it once since Ive been there and Im sure it will develop the computer work

for me is not finalized by any means. (DR)

74 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

All colleagues and three research coordinators similarly reported that there was

some potential for further use of the practice or of ICT more generallywithin the

topic or subject area, or in terms of cross-curricular links:

If we create a basic framework, we can substitute the information, change the information

and put it across any year group and do similar tasks at different levels but on different

topics, using broadly the same approaches. (RB)

All of the teachers also described how they had integrated either the TiPS practice

specifically and/or ICT more generally into their departmental schemes of work. (In

some cases this was a deliberate mechanism for extending the practice to colleagues,

as described below under Dissemination.) This progression had gradually led away

from classroom use of ICT as quite a big deal towards becoming part and parcel of

what you do (OL/AY). While the participants were clearly a motivated group originally, their technical expertise and pedagogy for using ICT were not necessarily well

developed. Over time they had shifted towards being confident, integral users of

ICT (Dawes, 2001).

Mechanisms for change

Mechanisms through which evolution of practice had taken place included trialling

pedagogic strategies over time and refining thembouncing ideas about to see what

works (RB); dropping unsuccessful features and extending them to new topic areas

or pupil groups. Lessons learned from trial and improvement included general ones,

most notably the development of more discerning use of ICT:

What perhaps the TiPS did do for some people in the school is question the effectiveness

of the use of ICT on learning. So were very well-versed now in seeing what is the point of

doing this. Could you do this better on paper or through dialogue? (LR/RE)

One teacher had moved away from an approach which tested whether ICT could

be employed for all activities within a topic series, and whether learning could be

devolved to the technology:

The work that Im actually doing using computers is much more focused rather than using

the computers for the sake of it, which I think was the big problem with the project that

we did. (DR)

Insights also related to the specific practice; for example one colleague described

the importance of leaving enough time for an introductory phase before conducting

Internet research, and for a final (plenary) phase:

We were tending perhaps to dive in too quickly to use the computer without enough reflection. What are our objectives? What are we going to use to get there? What search

engines are you aware of? (FE)

The other major mechanisms for developing practice over time were feedback from

colleagues, collaborative development, constant review and sharing of resources (this

theme is elaborated further under Dissemination):

ICT-supported classroom practice

75

I always like feedback on how well the booklets run, whether there is anything that the

students dont understand. The staff said that the students found that so difficult to do

wacky box first that. I actually sat and had to re-alter it. (JN/MV)

Because were able to collaborate on it together, it encourages us to then apply that

method to other topics as well (OL/AY)

This extension to new domains was corroborated by the colleague of this last pair,

who went on to emphasize the benefits of collaborative working for producing better

ideas and avoiding tunnel vision:

Were having a unified lesson planning approach we share resources, we flag up good

web sites on our Intranet, initially. (RB)

Another pair (VM/OT) described how colleagues assisted with updating of websites

and had new inventive ideas all the time which helped to improve search activities.

Strand 2 findings: dissemination of TiPS practice

Extent of dissemination to colleagues

Teachers involved in eight of the ten interviews had consciously and comprehensively

disseminated their practices within their own subject departments, such that all relevant

colleagues were reported to be using them in some form. A further teacher had moved

schools and reported some resistance to using ICT in his old department; his new

department was more receptive to change and the practice was starting to infiltrate.

The final teacher reported use of ICT by her colleagues but none that was directly

influenced by TiPS or herself as yet (although she planned to offer training).

Four colleagues were reported to have taken their own paths through adapting the

approaches or activities in some way, for example in design technology:

Weve reversed the whole booklet. We are all individuals you dont actually attack it

in the same way because weve all got different methods. What works for us wont necessarily work for the other one. (GR)

The need for cultivating a sense of ownership was also raised by an English teacher:

We did give a number of presentations to various audiences of what wed done and

hopefully thats been helpful to our other colleagues but I think people tend to find their

own way, dont they, through these things and try it out. (VM)

By contrast dissemination outside of departments was limited, although available

opportunities had been exploited. (This might be expected since some practices were

very subject-specific.) There was only one clear-cut case of successful whole school

dissemination. Here, materials pertaining to Internet research and lesson management had been distributed widely via a full staff meeting, teachers had talked to all of

the other departments and obtained feedback, and the approach was built into development work across the school. In three other cases, practices were beginning to

spread. One teacher had disseminated the practice outside the school through exchange

of ideas with a similar-minded head of department.

76 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

Teachers perceived a strong degree of potential for further sharing or demonstration of

their practice, especially within departments. In one case, the style and structure of a

teaching booklet produced was thought to be potentially useful in guiding other

subject (design technology) practices. In an English department, distribution of tools

on CD-ROM for analysing poetry was planned. Take-up of ICT-supported practice

by colleagues was in fact considered to be a lengthy evolutionary process:

They give their time to ProDesktop and learning it as and when they have to support

students being taught and its slow. (JN/MV)

You have to take a much longer term view if these projects are going to make a big and

lasting change, its got to have a longer time cycle somehow. Otherwise youre not

getting value for money. (FE)

Mechanisms of dissemination

Integration of practice into departmental schemes of work emerged in seven cases as

probably the most powerful means of disseminating the TiPS practices widely to

colleaguesthrough both encouraging colleagues to generate schemes collaboratively and in some cases actually making its use compulsory:

We all have ownership of the schemes of work because we work as a team to try and

develop them some of the ideas that came from the project were fed into [the] new

schemes of work. (VM/OT)

Ive learnt that the most effective way to make someone learn something as a teacher

within the context of technology is that you write it in the scheme of work and kicking

and screaming, whether you like it or not, as a teacher, you have to walk into a room on a

regular basis and deliver. (JN/MV)

Colleagues corroborated these accounts:

The A5 booklet has now been institutionalized. I, as head of science, did say Im really

impressed with this, I think its good and I made that very public, and made a public point

of including that in [the scheme]. (FE)

The latter example illustrates the pivotal role which heads of department in particular were found to play in disseminating practice. In two cases reluctant teachers were

recruited to the desired practice through this integration process, for instance:

Something else that [RE] has devised called a cyber-novel you get to a certain

climactic point and the kids then write the two alternative chapters, which are hyperlinked. When some people didnt get round to it we said, Right. Everyones got

to do this and the computer room has been booked for your group on these three days

and that way, it happens people might feel a bit bullied but we really think that all

the children are entitled to do this. (BR)

The originators played a key role in disseminating practice themselves less formally

through their proactive support for colleagues. In three cases there was a strong perception that colleagues required guidance, moral and practical support in getting to grips

with the new approaches, and teachers appeared more than willing to provide this.

Two participants highlighted the importance of demonstrating or working with

colleagues in order to break down resistance and barriers:

ICT-supported classroom practice

77

The first step is to try to show them what the potential is: This is how to do it, this is how

easy it can be, come and watch me teach this lesson once they get receptive theyll

start to appreciate that computers can work. (DR)

I think if you were able to increase the frequency [of] sessions where we physically

sit together and we all do then you would inevitably break down barriers to it that

way they gain confidence and learn it. (JN/MV)

By contrast, one teacher invited her colleague to observe some lessons but did not

see it as her role to provide specific guidance or resources: I gave her some web sites

but then I left her to it she wants to find her own feet (LL).

Support was mentioned as instrumental in dissemination by three colleagues

themselves, for instance: As I was coming up against obstacles and problems I

could then go back to [JN/MV] and theyll show me another little bit (GR).

One history colleague felt that colleagues from other subjects within his humanities

faculty would benefit from clear tasks to hold your hand through it (RB). Such hand

holding and a certain amount of cajoling was described by an English colleague:

If youre saying not only is the computer room booked for you but [RE] is going to come

too and show you how to do it and someone from ICTs going to be there as well! And if

you smooth out all the problems and say Its not going to be threatening and the kids

will really love it, you dont even have to do it, you can just come and watch and then

the next year you can do it yourself. In that way, the things tend to come through. (BR)

Physically sharing resources and approaches was a second important form of support

(mentioned by four teachers and one colleague). Mechanisms here included electronic

collation of materials, including opportunities to contribute good lessons or resources

to schemes of work or an Intranet. Careful preparation of user-friendly resources for

colleagues was mentioned.

Other aspects of the role of the originator in disseminating practice involved

exposition at department meetings of something that we can all use so that we all get a

feel for it (VC) or colleagues observing lessons and then hopefully com[ing] out and

do[ing] it themselves (DR). One colleague felt that personal contact of this kind

would be ideal but very expensive in terms of time and difficult to achieve (FE).

Opportunities for this were clearly dependent on levels of resource and willingness in

schools; a research coordinator elsewhere reported that her school financed a successful peer observation programme: you can go and watch people doing things that

you want to learn (BR).

Passing on experience of using ICT through training colleagues, on an individual

basis or in department meeting time, was another useful mechanism here:

When he learned ProDesktop first, he went on the training course, and when he came back

he said, Im going to teach you and my group at the same time. So he took the lesson and

I was a student (GR)

One colleague pointed out that merely including lessons in the scheme of work may

be insufficient and that the originator perhaps ought to sell herself a bit more in terms

of whats been achieved (FE). He believed that spontaneous realization of the benefits of a new practice was very rare and that teachers need to be involved in training

78 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

colleagues. While one teacher strongly preferred department level, personalized and

relevant training from colleagues to whole school training initiatives, his colleague

espoused the benefits of training over informal exploration:

I cant sit down for hours on end and play on a computer. Its not a plaything, its a tool

that I have to learn to use. I didnt learn to drive by driving a car round a field; I had

lessons. (GR)

There was some evidence of a perceived need for more training than was available.

One teacher expressed her view that in-service training on how to use the web as an

efficient teaching tool would be a very useful means of spreading good practice. A

research coordinator stated:

Its a question of finding time to fit it in and if you were to say the next entire INSET day

is going to be spent in departments with a focus on disseminating positive use of ICT,

youd get a lot more take-up. (BR)

In sum, a strong degree of departmental collegiality emerged throughout the interviews and this was summed up by a colleague who reported that he and his peers were

trying to drag each other along (GR) through sharing their evolving expertise.

Whether dissemination was planned or incidentalas in the informal conversations

described by one research coordinator (BI)teachers appeared to be embarking on

a joint learning enterprise where ICT use was concerned. However, this collegiality

and dissemination were mainly confined to subject departments. One research

coordinator attributed the lack of knock-on impact of TiPS to the isolation of

departments within schools:

I think schools do tend to be quitecollections of enclaves of different teachers and of

different subjects and the boundaries and borders between those really can be quite

distinct. Something going on in another subject area wont necessarily have been heard of

by another area or deemed to be of interest. (SI)

Factors of influence upon sustainability, development and dissemination

of practice

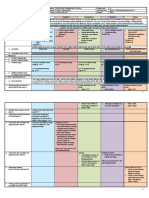

Three broad groups of factors were identified (see Figure 1) which variously influenced the processes of evolution over time and dissemination of practice for both the

teachers and their colleagues. Many of the factors emerged as both enablers and barriers to these processes and individual teachers comments reflected the aspects most

salient to their particular situations. The predominant themes are described in the

following analysis.

Figure 1. Distribution of factors relating to development and dissemination of ICT-supported practices

Organizational factors

Overall, extrinsic organizational factors or whole school characteristics were found to

have the biggest motivating influence on both sustainability/development and

dissemination of ICT-supported practice. The research coordinators provided independent evidence for this; indeed such factors were mentioned in all 21 interviews

conducted.

ICT-supported classroom practice

Organizational factors

Motivational factors

79

Pedagogical

factors

No. of teacher & colleague interviews

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

lc

ha

ng

Sc

e

ho

C

ur

ol

ric

et

ul

ho

um

s

+

IC

T

Te

pr

ch

io

no

rit

y

lo

gy

re

lia

Te

bi

ch

lit

y

ni

ca

ls

Tr

ki

a

lls

in

in

an

g

d

ex

pe

C

on

rie

fid

nc

en

e

ce

C

on

te

ch

fid

ni

en

ca

ce

l

in

ap

A

ffi

pr

ni

o

ty

ac

w

h

ith

ap

pr

oa

ch

Te

a

R

ch

es

er

is

ag

ta

nc

e

e

to

Su

ch

cc

an

es

ge

s

an

d

le

ar

ni

Pu

ng

pi

lm

ot

iv

at

io

n

rg

an

is

at

io

na

Te

ch

no

lo

gy

Ti

m

e

ac

ce

ss

Figure 1.

Development

Dissemination

Distribution of factors relating to development and dissemination of ICT-supported

practices

Access to technology resources was the most frequently mentioned factor in this

group. While provision had recently risen dramatically, competition for its use and

block booking of ICT suites meant that availability, especially within subject

departments, remained a problem. In addition to new types of software triggering

development since TiPS, provision of projection technology had greatly increased,

mirroring the national trend (interactive whiteboards in schools had more than tripled

in number over the last two years: DfES, 2004). Perceived advantages of projection

technology are numerous (see Becta, 2003b; Kennewell, 2004) and in our study the

introduction of whiteboards and data projectors had impacted very positively on

development of practice.2 These tools enabled teachers to model processes (such as

writing) using students work, to work more collaboratively with the whole class (e.g.,

on a history essay) and have a dialogue while youre working rather than merely

giving them instructions. Consistent and flexible access was seen as key to effective

use of projection technology:

You might need it just for two minutes at the beginning of the lesson but the current situation is where you have it and you feel obliged to squeeze every drop of blood out of it and

you dont get the best out of it. (RB)

However, even in the most well-resourced school, it was reported that teachers

were sometimes reluctant to use distributed forms of ICT because of the hassle

involved; for example time taken in fetching the laptop trolley, pupils logging on, and

in organizing sharing of machines: The smoother you can make that process, the

more likely you can get a take-up in the department (BR).

80 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

Moreover, system reliability was cited as a major issue in three schools; development of practice was impeded through lack of technical back-up, not through lack of

willingness and in one school lessons using ICT had become very, very high risk.

Organizational changes affecting school ethos or department culture since TiPSsuch

as new specialist school status, increased resource levels, changes in personnel and

prioritization of ICT by the schoolwere also perceived as having had a significant

impact on both development and dissemination. For example, bidding for technology

college status had engendered more of a focus on [ICT] in every aspect of the

schools work (BI). In another school, staff changes at senior level had led to an

increased focus on use of ICT for administrative and management purposes and this

had encouraged greater use of computing equipment generally; there was now said to

be a mindset that ICT has a role to play. In one very well-resourced school it had

become inherent and engrained within the culture. It was reported that staff training

was readily available, every department had a policy for ICT use and a nominated

ICT coordinator (see Case study). Despite the general commitment to developing

ICT that characterized each school, competing school priorities were reported as

having affected both development and dissemination of TiPS practices:

I dont think theres a general reluctance but it is a problem, particularly in light of all the

other things that have to be donethe Key Stage 3 literacy strategies, changes to the

SATs, changes to the GCSE papers and everything else. There isnt really time it sort

of gets pushed down the list of priorities. (AI)

One teacher highlighted the importance of having someone to drive the process

within the department. Similarly, where practitioners had moved or taken up other

responsibilities, uncertainties were expressed about how successfully an approach

could be maintained without the presence of the originator:

I dont actually teach it now, I just manage the teaching of it its all going to be devolved

to two completely new people, so itll be interesting to see how it pans out, what kind

of input is required by me to keep it robust. (RU)

Lack of time for familiarization with new equipment and for preparation was

mentioned as a constraint on both developing and disseminating practice, though this

factor was mentioned far less often by colleagues. One practitioner described how his

attempts to disseminate practice had been hampered not by lack of vision, but of

time: Its not that I dont know what to do, its that Ive not had time to do it (KE).

The increased planning time required for ICT-based workespecially involving use

of the Internethad ultimately deterred some enthusiastic colleagues from taking up

and developing new approaches:

They had some fantastic ideas on how they wanted to integrate Internet-type learning into

lessons and I think if given the time would produce fantastic lessons and schemes of

lessons, but in the end they are paid to be in a classroom. (VM/OT)

Subject Curriculum requirements such as the need to be doing research much lower

down the school, a much greater focus on poetry at Key Stage 4 in English and the

introduction of CAD/CAM in design technology had stimulated three groups of

ICT-supported classroom practice

81

teachers to develop their ICT-based practices. However, it was reported that the

demands of Curriculum coverage at Key Stage 4 made it more difficult to include

ICT-based activities than in Key Stage 3though more time was sometimes available

with lower ability groups where you dont have to go into the detail (DR).

Meeting Curriculum requirements had proved to be a powerful factor not only in

sustaining practice, but in disseminating it to colleagues:

When the Curriculum changed for Key Stage 4, Seamus Heaney was one of the key poets.

So many lesson plans, assignments and lessons that wed worked on, [departmental

colleagues] started to use and adapted them in their own ways. (LR/RE)

Similarly, elsewhere, focused activities devised during the TiPS project were

promoted confidently to departmental colleagues because: We knew now that it

worked It kind of ticks the right boxes as far as the National Curriculum goes

(VC).

The role of training in relation to disseminating practice was cited as influential in

three teacher interviews and referred to by four colleagues. In two schools, ICT skills

training for staff was readily available and this facility was seen as helpful in supporting staff who were keen to take up ICT-based practices:

Some people, rare people will connect with it, see how it affects them and they can

see Oh yeah, that will benefit, and theyll then build it into their teaching. Thats very

rare. You have to have an ongoing process youve got to have some form of training

for most people theres got to be that personal contact. (FE)

This view was also reflected in one research coordinators call for dissemination

activities to include more structured training, providing an action plan and continued support (SI).

Motivational factors

Two internal or motivational factors, namely teachers technical confidence and confidence in approach played a key role too, although they were linked twice as often to

dissemination, and thus more to colleagues confidence levels. The teachers involved

in TiPSwhile not experts initiallyhad subsequently used ICT regularly for over

three years and may therefore have developed their confidence to higher levels than

colleagues coming to it more recently. Many teachers had been involved in supporting colleagues through disseminating practice and the mechanisms they adopted are

outlined in the previous section. Lack of confidence in classroom use of technology

was viewed as a major inhibitor to take-up of TiPS approaches: It comes down to

people actually using the technology, building their own confidence and thinking

Yes, I can do this with a group of 30 students (VM/OT).

One pair spoke of staff who were very hesitant and nervous about using ICT, even

in the simplest ways. Their solution in helping them get over that barrier was to

shape the practice into more accessible mini packages (see Case study). The

colleague of this pair indicated that provision of laptops for staff had contributed to

growth of confidence and take-up of the TiPS practice.

82 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

Teachers and their colleagues highlighted the importance not only of developing

confidence and competence in use of the technology but also in the pedagogical

approaches at the heart of each practice:

I think people tend to take an individual lesson plan for a particular lesson but Im not

sure that they necessarily work in the way that we work but because its quite a long

road that youre on before youre confident about whats worth doing and what isnt, its

quite hard just to say to people, Heres a strategy. Off you go because with experience

you learn a lot of things which give you confidence about how to run the lessons, what you

really need is somebody who wants to come on the journey in the same way and fall into

a few pits (LR/RE)

One colleague felt that provision of additional guidance and accompanying tasks

would facilitate more effective use of the resources by other staff.

The emerging theme of affinity with a particular approach concerned the notion

that individuals were more likely to take up a practice if it resonated with their own

pedagogical ideas. For example, one colleague spoke of take-up of practice by new

members of staff who were very keen on that approach too. (The affinity theme may

be related to previous research illustrating that teachers who successfully integrate

ICT tend to be those with an innovative pedagogic outlook: see Harrison et al., 2002.)

The extent to which an individual perceived the approach to have immediate relevance to their own teaching area was seen as important too.

Finally, technology skills and experience, resistance to change, and teacher age

(younger teachers were construed as natural and innovative users of ICT) were also

influential.

Pedagogical factors

All of the teachers and almost all of their colleagues considered the practices they had

developed to be largely successful in terms of enhancing pupils learning. The terms

in which success was perceived reflected the spectrum of different approaches which

teachers had developed and often related to the affordances of the technology, for

example facilitating more collaborative working with pupils during lessons, widening

the range of available resources and enabling links to be made with the everyday world

outside school. In two casesEnglish (YL/JY) and design technology (KE)

improved examination results had reportedly been achieved in modules incorporating

work with ICT. For the two science teachers who had produced a set of practical

guidelines for using the Internet in teaching, success was seen in terms of the generic

nature and applicability of the principles they had proposeda view corroborated by

their colleague:

So I was interested to see what their research had to say, because I was a bit concerned

whether the students were getting as much out of [using the Internet] as they could. It

seemed to me that the kids were treating it a bit like a jolly, etc. So it was useful reading

through what theyd put because the next lesson that I taught was radically different;

much, much more successful, and subsequent lessons have been. I have to say, it did

work. (FE)

ICT-supported classroom practice

83

The need to show evidence of genuine, useful learning was a strong factor for two

English teachers:

I do think that the whole business of feeling the need to be able to defend what youre

doing in terms of genuine, useful learning, that was really brought home to us [by

TiPS]. That has informed what weve been doing ever since. So even when we

seem to be moving quite slowly in terms of further progress were not that bothered

by that because were aware that real progress, its something quite interesting. (LR/

RE)

Their colleague (recently appointed head of department, who had previously

developed similar ways of working) described success of the practice in detailed

terms, closely linked with pupil motivation:

Somehow, annotating poetry on the computer is more interesting than annotating poetry

in a book. So youve got this whole motivational force behind it, but its useful as a way

in to looking at the actual poem and its not the be all and end all, you know, sort of

colouring in the poem and rearranging it but if you can grasp their attention that

way get them to do a little bit of feature-spotting, having done that bit, its more easy

to say OK, well why is that being used? Whats the effect of that? Whats the overall

effect of the poem? Can you see how these different elements are kind of fitted together?

(BR)

Pupil motivation was an important factor in accounts relating to development and

to a lesser extent, dissemination. These findings resonate with other recent work

concerning both the motivational effect of ICT on pupils (Passey et al., 2004) and the

critical impact of teacher beliefs about the benefits of classroom ICT use for students

(e.g., Cox, 2004; Ruthven et al., 2004; Tearle, 2004). Software tools were seen as

enabling pupils to process material more efficiently and to produce neater work: Its

quite complex because theyre dealing with so many different pieces of evidence and

the computer actually helps them record it but also helps them sift it quite quickly

(OL/AY).

One group of teachers strategically planned their use of ICT to motivate pupils

towards the subject trying to do things that kind of we hope will switch children on

to English (VC). The two history teachers spoke of ICT providing a really exciting

experience and in design technology, use of a design package encouraged pupils to

see and learn and get inspired.

However, comments relating to dissemination also focused on the need for discriminating use. For example, one pair described how, during their early work with ICT,

colleagues had been attracted to it because screens looked lovely and jazzy and the

class looked absorbed and interested whereas pupils were actually just labelling

things they didnt understand and that wasnt productive (LR/RE). Similarly, a

research coordinator in another school noted that pupils habituating to the new technology could obstruct wider dissemination.

The following case study brings together some of the themes outlined in previous

sections. It describes in some detail the comparatively favourable school context in

which two of the TiPS English teachers (LR & RE) were working. It highlights some

of the institutional features that were reported to have influenced the development

84 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

and dissemination of their practice over time. Contrasts are then made with other

departments in our sample.

Case study: evolution of ICT-supported English practice in a highly

resourced school

The school (SC) is a mixed sex, non-selective village college in Cambridgeshire with

1150 pupils aged 11 to 16 years old. It is a foundation training school, with specialist

sports college and leading edge status (gained in 2003)all of which have attracted

additional funding for expansion of facilities. Two per cent of students are entitled to

free school meals and an outstanding proportion, 85%, achieved five A*C grades at

GCSE in 2003 (the year of our follow-up study). Access to ICT resources increased

significantly during the three years between our studies through provision of four

additional computer rooms, laptops for every teacher, data projectors, several sets of

pupil laptops and development of an intranet to enable sharing of resources. The

English department now has a dedicated ICT room and two data projectors, and

plans to install a projector in each of the six teaching rooms within the next year.

Every department has an ICT policy and a nominated ICT coordinator whose role is

to identify ICT dimensions of courses and facilitate access; staff ICT skills training

is offered at all levels by an advanced skills teacher.

A recent Ofsted report (2004, p. 11) indicates that the majority of teachers are

actively involved in developing their work by undertaking research or by leading

innovation, within a culture and atmosphere where innovation and experiment are

the norm. The school is on the list of the 123 most outstanding secondary schools

in England.3 Provision and performance in English are deemed excellent:

The department is an enthusiastic and reflective team, with a strong interest in developing

and sharing good practice. Several members of staff are involved in action research projects

which directly benefit the students, including work on the modelling of writing using ICT.

(Ofsted, 2004, p. 32)

Throughout the school peer observation is supported by funding from the central

budget to cover each teacher for three periods per year. Since the school is successful

with lots of initiatives on the go at once, departmental training time is mainly dedicated to current whole school programmes. However the head of department (BR, a

highly enthusiastic, research active, innovative teacher who works widely with ICT)

has encouraged staff to use their peer observation time to develop ICT-based practice.

The TiPS project of LR and RE focused on the use of text processing tools to assist

the (re)organization and (re)presentation of poetic texts so as to explore form, content

and genre. They aimed to improve pupils capacity to identify techniques by which

writers persuade and affect. For example, one task involved pupils highlighting

instances of alliteration and assonance and annotating these electronically with

comments on the perceived effectiveness of the poetic devices. The teachers had

subsequently developed this approach to create toolkits or mini-packages containing

source material and suggestions for suitable analysis techniques. Their initial decision

to focus on poetry had been driven by a requirement for greater emphasis on this

ICT-supported classroom practice

85

genre in the Key Stage 4 syllabus; through trialling and refining the approach they

were able to pass on to colleagues the things that work.

Another aspect of LR and REs work was the use of hyperlinks to support the

construction of new texts. Whilst the initial inclusion of this approach within departmental schemes of work did not result in universal take-up, the head of departments

subsequent strategy of making it mandatory, pre-booking the computer room, having

both a TiPS teacher on hand to demonstrate the approach and an ICT teacher to

troubleshoot technical problems and provide skills support, proved highly successful

and all staff in the department now use the materials. Her rationale for the presence

of an ICT teacher was to enable the subject teacher to continue English teaching

and because you cant ask teachers to teach a skill they havent got themselves. In

order to ensure that pupils were equipped with specific technical skills (for example

hyperlinking), these had been written into the global ICT schemes of work. (This

contrasted with School VC where TiPS teachers commented on the lack of such

synchronization: its like were laying the foundations for the ICT department for

what comes later in other areas.)

At School SC, although equivalent resources and training opportunities were

available across all departments, another TiPS practice (using simulation software to

support teaching of electronics in design technology) had been less widely disseminatedpartly because it related to a specialist area but also because of the identified

need for a person to drive it all. Here, the TiPS practitioner was also head of department but additional responsibilities as an assistant principal had left little time for

developing this aspect of departmental practice. Indeed, despite all of the resources

and support available in the English department, carving out time was likewise a

major issue for the TiPS teachers there in developing and disseminating their work.

Both had diverse, complicated jobs; one was an advanced skills teacher and the

other had again been promoted to assistant principal.

Contrast with other contexts: access to resources

The ease of access enjoyed in this school was unique amongst schools in our study;

for example, it contrasted with the situation at School MC where, despite increased

provision of resources, the vision of interactive whiteboards, projectors for everybody, every teacher hav[ing] a laptop that works was seen as a long way in the

future.

Similarly, English teachers in School VC described how the need to book computer

rooms several months in advance had led to ICT-based approaches being mainly

restricted to groups where there was a specific curricular or examination coursework

requirement to include it. In a third English department (TC), the TiPS practice had

not been widely disseminated or taken up. This was largely because of limited availability of resources (although this was one of the most well-resourced schools at the

time of TiPS) and colleagues lack of technical confidence. The research coordinator

at this school stressed the need for dedicated time and training if research outcomes

were to affect departmental practice.

86 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

Contrasting approaches to development/dissemination within departments

Collaborative development of practices was notable in two other departments

where dissemination had also been widespread, although the mechanisms for

dissemination contrasted with those of the SC English department. For example,

the open plan layout of the design technology department in School MC meant

that colleagues tended to be aware of each others teaching activities in the course

of daily routine although there was no formal provision for peer observation.

Departmental meeting time was allocated for hands-on software training of

colleagues. Support for mandatory use of the TiPS approach was

provided through informal collegial departmental activity and collaborative

development:

We run an open department and we walk through each others lessons regularly so we

are aware that things are done in our own style. But at the same time, we all have our

coffee together, we always have informal discussions and we say, You know when Im

doing this, Im finding this is happening and A will say, Well, have you tried doing this?

and B will say, Have you tried doing that? (GR)

In the history department at School CC, the TiPS practice had not been built into

schemes of work, but had been taken up on colleague recommendationthough it

appeared that neither formal nor informal opportunities to see the approach in

action existed here. Nevertheless, teachers in this department worked closely

together and emphasized their commitment to collaborative development of

resources and methods:

We have a culture as a department, which is a questioning culture and an ideas culture

and if people have got things to say or do which they think are an improvement of what

weve already got in place, or a different way of looking at them, then I think we are all

happy to embrace that really, arent we? (AY)

I find that we always tend to produce better materials when we work as a department So

the two of you sit and one says, Yeah, Ive done this. And I think you get better ideas.

(RG)

This case study illustrates the interplay between factors influencing the development and dissemination of practice: whilst initiation of the TiPS approach was predicated on the English teachers desire to harness technology to support curricular

goals, access to reliable resources and a supportive organizational culture enabled

them to develop it. The department leaders affinity for similar ways of working, her

leadership skills, and a strong degree of cooperation between the ICT and subject

departments were further factors in successful dissemination and take-up of

practice.

The pedagogical motivation to identify and develop approaches that work was

also evident in less well-resourced departments, where dissemination of practice had

nevertheless been achieved through collegial activity. However, even in contexts

where neither resources nor motivation were lacking, competing professional

responsibilities sometimes impeded evolution of practice.

ICT-supported classroom practice

87

Discussion

This study examined the evolution over time of ICT-supported classroom practice,

within a climate of significant investment in technology resources, teacher training

and support. However, the literature suggests that contextual factors may mitigate

against development and dissemination of ICT-supported practice (see Cuban,

2001; Becta, 2003a) whilst others may act as enablers (see Scrimshaw, 2004). It was

notable, therefore, that all of the ten teams of participating teachers were found to

have sustained and further developed the particular practices they had initiated

during their action research projects three years previously (despite being unaware

that a follow-up study would ensue). To some extent this may be explained by the

fact that the sample were originally practitioners who were keen to develop their use

of ICT and volunteered to take part in the TiPS research. Over time, however, they

have become much more experienced and confident in employing ICT in a diverse

range of ways, such that use has reportedly become inherent and engrained within

their teaching, learning and management processes (Day, 2004).

The key mechanism underlying evolution of the teachers practice and thinking was

trial and improvement of pedagogic strategies; the critical reflection upon success

which this involved corroborates the conclusions of Loveless et al. (2001). Undertaking such a trialling process may explain why the more cautious, critical approach

exemplified by some of these teachers and their departmental colleagues when

interviewed in focus groups nearly four years before (prior to the TiPS study) was

much less evident here. At that time and during their TiPS projects teachers were

formulating and trialling new mediating strategies which were designed to use ICT

discerningly, to add value to existing practices and to focus pupils attention onto

underlying learning objectives (Hennessy et al., 2005a, b; Deaney et al., in press). It

is these successful practices which have persisted over time and subsequently been

further developed and disseminated to colleagues.

Our previous research with core subject teachers at secondary level additionally

indicated that practitioner knowledge and thinking is tied to specific subject

cultures, pedagogies and activities (Ruthven et al., 2004). We observed a strong

degree of collegiality here too such that subject departments were acting as robust

communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991) within which new practices

involving ICT were constructed, shared and built upon. Dissemination of ICTsupported practice to departmental colleagues was reported by the vast majority of

teachers involved in this study. Colleagues perspectives proved invaluable here,

partly in corroborating teachers views (there was no conflict between the two

groups although emphasis varied sometimes), but especially in providing further

insight into the mechanisms and factors underlying dissemination. Finlayson,

Wardle and Rogers (2003) emphasized the important role of experienced colleagues

who exemplify good pedagogy in teaching with ICT and possess willingness to give

advice and share their experiences within the department. In our study, the stimulus

of informal or formal opportunities for actually seeing such practice in action was a

key motivating influence for colleagues: Seeing what was possible could I be

88 R. Deaney and S. Hennessy

doing something similar? How would I use it with my class? And if you can see it

fits, you do it (FE).

Figure 2 illustrates how teachers multifaceted motivation and the mechanisms for

developing and disseminating their classroom use of ICT are construed as closely

interrelated. The proposed directional links between the diverse contextual (whole

school level), external (national policy), and internal (teacher level) factors operating are portrayed. These links are potential, depicting the multiple possible pathways

within development and dissemination processes. For the sake of simplicity, the

figure combines factors influencing both development and dissemination (nuances of

the differences operating here were portrayed in Figure 1) in order to provide a more

global overview of the interrelationships between key factors and mechanisms in the

evolution of practice within departments (only those affecting both processes to some

degree are included).

We suggest that the National Curriculum and other policy requirementsticking

the right boxesare initially influential to some extent in take-up and integration of

ICT-supported practices. However, once practices are established and trialled, then

teacher confidence, skill and enthusiasm for using ICT, their strong pedagogic

beliefsdefending what youre doing in terms of genuine, useful learningand

affinity with particular approaches may become more significant motivational factors

underlying sustainability of practice over time and generalizability to further contexts.

Although these pedagogical and motivational influences constituted both barriers and

enablers in different contexts, proactive colleague support, cascade training and physical sharing of approaches offered mechanisms for facilitating take-up of new strategies, especially by less experienced users of ICT.

By contrast, a further mechanism for successful practice becoming established