Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Epistaxis: S. H. MD

Hochgeladen von

Lilia ScutelnicOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Epistaxis: S. H. MD

Hochgeladen von

Lilia ScutelnicCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

OTOLARYNGOLOGY FOR THE INTERNIST

0025-7125/99 $8.00

.OO

EPISTAXIS

Luke K. S. Tan, MD, MMedSci, FRCS,

and Karen H. Calhoun, MD, FACS

Patients presenting with epistaxis are anxious and fear bleeding to death.

Although death from epistaxis is rare, it can occur, and significant morbidity is

relatively common.5,34 Although most pediatric epistaxis is treated on an outpatient basis, older patients (>60 years old) more often require hospital admission.25,44 Initial management of epistaxis is directed at stopping the bleeding,

and long-term treatment is directed at discovering and correcting the underlying

cause. This article updates current management options.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS IN EPISTAXIS

The blood supply to the nose arises from the internal maxillary and facial

arteries via the external carotid and the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries

via the internal carotid artery. The anteroinferior septum (Littles area) is supplied by a confluence of both systems (Kisselbachs plexus). Littles area is a

common site of epistaxis because it is ideally placed to receive environmental

irritation (cold, dry air, cigarette smoke) and is easily accessible to digital trauma.

This area is easy to access and treat. Bleeding arising further within the nasal

cavity can be difficult to reach. Surgical ligation of the contributing arteries can

be challenging because of their deep location and complex anatomy.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Much epistaxis ceases with pressure (digital or packing) over the bleeding

point. An intact coagulation system with accumulation of platelets and clot

formation is required. Abnormal platelet numbers or function or any abnormal-

From the Department of Otolaryngology, University of Texas Medical Branch (KHC,

LKST), Galveston, Texas; and Department of Otolaryngology, National University of

Singapore, Singapore (LKST)

MEDICAL CLINICS OF NORTH AMERICA

VOLUME 83 * NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1999

43

44

TAN & CALHOUN

ity in the coagulation cascade leads to failure of clot formation and persistent

bleeding.

CAUSE

Epistaxis results from an interaction of factors, damaging the nasal epithelial

(mucosal) lining and vessel walls. The major causative factors include environmental factors (humidity, temperature), local factors (trauma, anatomic abnormalities, inflammation, allergies, iatrogenic, tumors), systemic factors (hypertension, platelet and coagulation abnormalities, renal failure, alcohol abuse), and

medications affecting clotting (anticoagulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs [NSAIDs]).

Environmental Factors

Cold, dry air increases cases of epistaxis. In countries with seasonal climates,

hospital admissions for epistaxis increase during the winter months.24,44, h1 Patients were admitted at a rate of 0.829 patients per day for temperatures less

than 5C compared with 0.645 patients per day for temperatures between 5.1"C

and 10C.61Most had some form of dry air heating, without humidification, in

their homes.

Nasal ciliary activity decreases as temperature drops. Normal ciliary activity

(at 32C to 40C) occurs at about 15 Hz frequency, dropping to less than 5 Hz

below 20"C.lh Although extremely dry air is known to promote epistaxis, the

exact humidification as a preventive measure remains undefined. Temperatures

of above 52C have been associated with cellular damage.56

Local Factors

Trauma

Nose picking and accidental injury are the commonest traumatic causes of

epistaxis. Except with severe facial trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents, this

epistaxis is usually from an anterior nasal source and easily treated.lR

Nasal Septa1 Deviation

Nasal septal deviation is common, but its role in epistaxis is not certain. In

one study, 16% of patients with severe refractory epistaxis had marked septal

deviation.z3In another study of patients with recurrent epistaxis, 81% had septal

The epistaxis group also had a

deviation versus 31%)in the control

higher incidence of radiologically demonstrated septal deviation compared with

the control group (62% versus 37% [P<.02]). The bleeding tended to occur from

the side to which the septum was deviated. Exactly how a septal deviation

could cause bleeding is not clearly established. Because septal deviations do

cause nasal obstruction turbulent air flow, this may cause abnormal mucosal

drying, making the mucosa more susceptible to bleeding.

EPISTAXIS

45

Iatrogenic

Septal, turbinate, nasal, sinus, or orbital surgery can be followed by epistaxis. Blood-stained nasal discharge is common in the initial week or two after

surgery. Severe epistaxis can occur, especially after partial turbinate resection

(0.9% to 8.9%).14Management of such patients is aimed at controlling the bleeding and contacting the surgeon to provide appropriate follow-up.

Inflammation (Infection and Allergy)

Epistaxis can result from nasal lining inflammation, with acute respiratory

infections, chronic sinusitis, or allergic rhinosinusitis. In children and the mentally disabled, intranasal foreign bodies cause unilateral foul-smelling discharge

that can be accompanied by epistaxis. Children with both nasal allergy symptoms and positive skin tests have more frequent epistaxis (20.2%) than those

with symptoms alone (9.9%),positive skin test alone (3.4%),or neither symptoms

nor positive skin test (2.1%). This study suggests that allergic rhinitis predisposes

to epistaxis, either by mucosal irritation or possibly by the atopic state contributing to a hemostasis

Tumors

Epistaxis can be the only symptom in patients with a nasal tumor. In

adolescents, the most serious cause of recurrent epistaxis is the intranasal tumor,

juvenile angiofibroma. Other neoplastic causes of pediatric epistaxis include

papillomas, polyps, and meningoceles or encephaloceles (infants).8 In adults,

almost any benign or malignant intranasal tumor can present with epistaxis.

Intranasal lesions can sometimes be seen by looking in the nose with the

otoscopic ear piece. Biopsy of intranasal lesions is approached with caution

because biopsy of highly vascular lesions, such as a juvenile angiofibroma, can

cause significant blood loss and morbidity.

Chemicals

Many airborne irritants and toxic chemicals (sulfuric acid, ammonia, gasoline, chromates, gl~taraldehyde)~~

irritate or harm the nasal mucosa, resulting in

epistaxis. Cigarette smoke, primary or secondary, is another common irritant.

Systemic Factors

Hypertension

Although hypertension is often cited as a cause of epistaxis, several large

studies have shown no higher rate of underlying hypertension among epistaxis

patients than in patients without epi~taxis.~,

b7 Hypertension patients taking

diuretic or methyldopa medications may have more epistaxis than those taking

P-blockers (60Y0).~Hypertension at the time of epistaxis treatment may be anxiety

related, returning to normal on control of the epistaxis and r e a s s u r a n ~ eEpi.~~

staxis patients with hypertension must be followed after control of the bleeding,

to ensure that blood pressure returns to normal on control of epistaxis because

some are found to have underlying hypertension requiring ongoing treatment.

46

TAN & CALHOUN

Renal Disease

Persistent epistaxis may be encountered in chronic renal failure patients

undergoing hemodialysis, but the true incidence remains unknown." Contributing causative factors may include elevated prostacyclin levels (platelet antiaggregatory activityy and prolonged use of low-molecular-weight heparin.54An

8% incidence of septa1 perforations has been noted in renal failure patients.

Localized irritation caused by turbulent air flow around the perforation could

also contribute to epistaxis in these patients.'

Alcohol

Heavy alcohol consumption increases the risk of epistaxis. The same platelet

reactivity inhibition that provides a protective effect for the coronary arteries

may also increase bleeding time, making epistaxis more difficult to

50

Bleeding risk, however, was not linearly related to alcohol consumption, with

those consuming 1 to 10 alcoholic drinks per week most affected and those

drinking more than 10 drinks per week less affected. Rebound of platelet activity

may explain this finding, but the mechanics have yet to be elucidated. The use

of NSAIDs did not confer an additional risk of increased bleeding

Coagulation and Vascular Abnormalities

Patients with hereditary conditions, such as hemophilia, von Willebrand's

disease, and thrombocytopenia, frequently experience epistaxis. Thrombocytopenia can also occur with hematologic malignancy, chemotherapy, or viral infections, such as dengue hemorrhagic fever2]and human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV),I5 or can be idiopathic.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia patients are particularly prone to

epistaxis pr0b1ems.I~The abnormal vessel walls and focal endothelial degeneration contribute to refractory epistaxis, which can be challenging to manage.

Treatment is aimed at decreasing the frequency of bleeds and need for transfusion because permanent cure is not possible.

Medications

Numerous medications interfere with normal clotting. NSAIDs (including

aspirin) are probably the most common, with up to 75% of epistaxis patients

using one of these medication^.^^ One study found that 42% of epistaxis patients

were taking warfarin, dipyridamole, or NSAIDs versus 3% of the nonepistaxis

control group.hhThese medications interfere with the cyclooxygenase pathway

in arachidonic acid metabolism, inhibiting platelet a g g r e g a t i ~ n .One

~ ~ author

suggested that a history of epistaxis may be a relative contraindication to the

use of NSAIDS.~~

In addition, because 74% of aspirin use is self-administered,

the public needs to be made aware of the relationship between aspirin and

nosebleeds as potential side effects.2

Other medications associated with epistaxis include thioridazine, topical

hyperosmolar sodium chloride, and dipyridamole (Persantine). Epistaxis resolving when the drug is stopped has occurred with thioridazine. The nasal mucosal

drying from the anticholinergic effects of this low-potency phenothiazine, coupled with home heating in the dry winter season in hypertensive patients was

thought to be the underlying cause of epistaxis.z2Dipyridamole inhibits adeno-

EPISTAXIS

47

sine diphosphate and collagen-induced platelet aggregation, enhancing disaggregation and prolonging bleeding time.4zEpistaxis has also occurred in a patient

using hyperosmolar sodium chloride (2%) eye drops.2yThe patient developed

dry nasal mucosa, presumably from osmosis, when the eye drops arrived in the

nasal cavity via the nasolacrimal duct. The problem resolved when sodium

chloride ointment was substituted for the drops. Use of steroid nasal sprays can

also be complicated by epistaxis, which is usually mild and stops after cessation

of use of sprayz4

MANAGEMENT

There are three levels of epistaxis management: (1) first-aid measures, (2)

acute management, and (3) interventions.

First-Aid Measures

In one series of patients taking systemic anticoagulants, 25% had experienced epistaxis in the previous year. Less than half of the patients could think

of a single first-aid measure to stop nosebleeds. Clearly, additional education in

this at-risk population could reduce both morbidity and patient anxiety.

First-aid measures include the following:

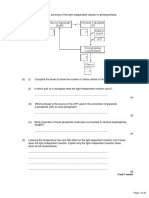

1. Digital compression. Although so simple as to seem reflexic, fewer than

50% of emergency department personnel could describe the correct site

to apply digital pressure in a nosebleed (Fig. l).3R

A swimmers clip has

also been used for epistaxis.62

2. Cotton or tissue plug in the nose. Patients often arrive in the office with

a piece of tissue pushed into the nostril that has been bleeding.

3. Bending forward at the waist. This position allows gravity to keep blood

flowing out the nostrils, rather than posteriorly down the throat.

4. Spitting out any blood that trickles down the back of the throat. The

patient is prevented from swallowing large amounts of blood.

Figure 1. Digital compression over the nasal alar and anterior septa1 area is effective

against most anterior bleeds.

48

TAN & CALHOUN

5. Cold compress on nasal bridge. This practice has a vasoconstrictive effecV5

Acute Management

Hypotension associated with epistaxis can precipitate acute myocardial

events or aspiration, sometimes leading to death. The patient with an actively

bleeding nose is apprehensive and often has reactive hypertension, accentuating

the bleeding. The basics of airway, breathing, and circulation remain key principles. Securing the airway via endotracheal intubation or trachesotomy in the

severely injured unconscious patient allows suctioning and packing of the nose

and, if necessary, the oral cavity and pharynx. Oxygen ensures good systemic

oxygenation, especially important in patients with underlying cardiopulmonary

disease. Intravenous access is established in all patients presenting with active

epistaxis because significant bleeding has usually occurred before the patient

seeks medical attention. When inserting the intravenous line, it is usually convenient to obtain blood for complete blood count and, if clinically indicated, type

and screen, coagulation profile, and electrolytes (in anticipation of surgical

intervention).

An assessment of the amount of blood lost is made from the history,

including the onset of the bleeding, precipitating factors, duration and quantity

(i.e., number of soaked towels), past history of epistaxis and treatment, and

history of blood dyscrasias. In adults, a history of medication (including

NSAIDs, anticoagulants), hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus,

and alcohol abuse may influence management. In children, a history of epistaxis

with unilateral nasal discharge alerts the physician to the possibility of an

intranasal foreign body. Consent for blood transfusion is recommended. The

vital statistics (blood pressure and pulse) of the patient should be charted.

The patient is supplied with folded gauze 4 X 4 pads to soak up blood

trickling from the nose. A chart is started to keep track of the number of pads

required, as further assessment of the amount of blood lost.

Local Compression

Thumb and index finger nasal compression pressure is used as the first

measure by the physician while other treatments are being instituted. Local

finger compression should be employed for at least 5 minutes to allow formation

of a hemostatic plug over the bleeding vessel.

Cauterization

Most epistaxis originates in the anterior nasal cavity, often in Littles area.

Effective local vasoconstrictive measures include pseudoephrine (Afrin), phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine), or epinephrine (1:10,000) applied to the area on

cotton pledget.

The area of bleeding can be cauterized. Silver nitrate is the most convenient

cauterization agent, available in ready-made sticks. Local anesthesia with 4%

lidocaine solution (applied by cotton pledget for 5 minutes) can reduce the

stinging of cautery. Accurate identification of the bleeding points and a good

light for intranasal examination are the keys to successful cauterization. The

temptation to cauterize a large area of the septum to cover all bleeding points

should be resisted. The authors routinely use a cotton-tipped applicator to

EPISTAXIS

49

mop up residual silver nitrate after application, to prevent local damage to the

underlying perichondrium. Postcautery, antibiotic cream or ointment is applied

to the cauterized area twice a day for 5 days to prevent crusting and infection.

Both sides of the septum should not be cauterized at the same time because of

the risk of septal perforation. Repeated cauterization in the same area can also

lead to septal perforations.

Other Measures

Other local measures include

1. Electrocautery.

2. Other chemical cautery (trichloroacetic acid).

3. Light packing with petroleum jelly (Vaseline) gauze.

4. Direct endoscopic electrocautery (detailed later).

5. Hemostatic chemical agents (thrombin-soaked absorbable gelatin powder [Gelfoam], oxidized cellulose [Surgicel],microfibrillar collagen [Avitene], porcine fat, oxymetazoline, or calcium alginate fiber [Kaltostat]).

6. Oxymetazoline hydrochloride (an imidazole derivative) is a topical vasoconstrictor commonly used as a nasal decongestant.28Of 60 patients

coming to an emergency department with epistaxis, there was a 65%

success rate with oxymetazoline alone. A further 18% of patients required silver nitrate cautery, and the remaining 17% required nasal packing.

7. Cryotherapy. This procedure for applying cold temperatures within the

nose to control epistaxis reportedly has less morbidity than other local

methods.zo It requires a machine capable of delivering the necessary

temperature to freeze the target tissues.

8. Hot-water irrigation. Success in treatment of epistaxis has been reported,

although patient compliance is variable.5h

9. Desmopressin (1-desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin) spray. Desmopressin spray has been effective in decreasing the duration of e p i s t a x i ~and

~~

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.s7

10. Laser therapy, diathermy, septodermoplasty, and other surgery. Surgery

has been advocated for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia with variable success.'", 4y, 63

Anterior Nasal Packing

Packing is needed when local measures are unsuccessful in controlling

epistaxis. Nasal packing is an uncomfortable procedure and can have lifethreatening complications, anterior packing less so than combined anteriorposterior packing. Classic anterior packing is performed with Vaseline-impregnated narrow gauze, placed in the nose until sufficient pressure exists to tamponade the bleeding. Although the tidy textbook diagrams of layered packing are

somewhat misleading, the general goal is to place the packing from the back

and bottom of the nose forward. A training model for nasal packing has been

reported to improve confidence and competence in the procedure.5y

Other options for anterior nasal packing include synthetic sponge packs

(tampons) such as Merocel that expand when moistened or balloon packing.

Merocel packs are easy and quick to insert and can be used for bilateral epistaxis

as well. The success rate of such packing exceeds 90%, even when performed

50

TAN & CALHOUN

by inexperienced physician^.^^ Both nasal tampons and gauze packing are efficacious and well t~lerated.~

After anterior packing, the oropharynx is inspected. If blood is still visible

trickling from the nasopharynx, either the anterior pack is suboptimally placed,

or there is a posterior nasal bleeding source. The nasal cavity measures about

7 cm from columella to nasopharynx, so the most common error in anterior

nasal packing is failure to pack adequately the posterior aspects of the anterior

nasal cavity.

Adequate lighting and long forceps (bayonet or Tilley's nasal packing forceps) are necessary for placement of an effective anterior gauze pack. Gauze

coated with BIPP (bismuth iodoform paraffin paste) can be left in the nasal

cavity for up to a week with low risk of infection. Vaseline gauze packing is

usually removed by 72 hours. Antibiotic prophylaxis is usually administered.

Elderly or frail patients with anterior nasal packing and most patients with

posterior nasal packing should be hospitalized for oxygen supplementation,

intravenous hydration, bed rest, and mild sedation. Because bilateral nasal

packing obstructs the nose and prevents nasal breathing, it often causes hypooxygenation. Anterior-posterior nasal packing with sedation is accompanied by

decreased arterial oxygen tension and altered pulmonary mechani~s.~

Oxygen is

usually administered via face mask with anterior and posterior packing (unless

the carbon dioxide is elevated). Sedation is carefully titrated, keeping in mind

the patient's cardiopulmonary status.

Other materials used for nasal packing include Kaltostat, Ativene, and

porcine fat (salt pork). A randomized trial comparing Kaltostat and bismuth

tribromophenate (Xeroform) showed similar efficacy and patient a c c e p t a n ~ e . ~ ~

Ativene successfully controlled 77% of idiopathic anterior epistaxis and can be

useful in hereditary telangiectasia epistaxis60Salt pork has been used for nasal

packing in patients with thrombocytopenia, commonly secondary to renal failure

or medications. Homogenates of salt pork contain an aqueous factor that serves

as a platelet substitute, inducing platelet aggregation and enhancing adenosine

diphosphate and collagen-induced aggregation. The pork fat is less irritating to

the mucosa on removal than gauze

This material is not used in patients

who avoid pork for religious reasons.

Posterior Nasal Packing

Only about 5% of epistaxis originates from a posterior nasal source." The

posterior nasal space is cylinder shaped, opening anteriorly into the nasal cavity

and posteriorly into the nasopharynx. Packing in this space tends to fall back

and down, into the oropharynx. To pack the posterior nasal cavity, a conforming

pack is first placed in the nasopharynx, secured anteriorly near the nostrils.

Gauze or other anterior packing can then be firmly placed against this resistance.

Classically a posterior pack is made of rolled gauze secured with umbilical

tape, although balloon packs are sometimes used (Foley catheter, Brighton Balloon, Simpson Balloon). Posterior pack insertion begins with passing a rubber

catheter through each nostril, into the oropharynx. They are grasped here and

brought out anteriorly through the mouth. Long ties attached to each side of the

gauze pack are attached to the catheters, and the catheters are gently withdrawn

through the nose, leaving a gauze pack held in the physician's hand, with the

attached long ties entering the mouth and exiting both nostrils. With gentle

traction on the nostril ends, the pack is pulled and pushed into the oropharynx,

then tucked up into the nasopharynx. The mouth ends of the ties are left long,

to be grasped later and used in pack removal. The nostril ends are secured

EPISTAXIS

51

anteriorly, usually around the columella. Care is taken to pad and protect

the columella from excessive pressure that could cause ischemic necrosis. This

unpleasant procedure can be performed under mild sedation, but use of general

anesthesia when possible is a kindness to the patient. Posterior packs are usually

left in place for 48 to 72 hours because earlier removal is associated with an

increased risk of rebleeding.

An alternative to posterior packing with gauze is balloon catheters inserted

in the nasopharynx via the nostrils and inflated with sterile water. The balloons

are secured anteriorly using a clamp (e.g., umbilical cord clamp). Either Foley

catheters or balloons designed specifically for the nasopharynx can be used. The

balloons have a tendency to deflate with time, and volume can drop by 30% or

more in 72

The authors usually deflate the balloons at 48 hours and

remove both anterior and posterior packings at 72 hours.

Complications of Nasal Packing

Nasal packing can be complicated by death.5 Aspiration of blood, cardiopulmonary failure secondary to hypoxia, and toxic shock syndrome have led to

mortality in patients with epistaxis. Complications in nasal packing include

1. Nasal trauma from the packing.

2. Nasal-vagal response (bradycardia, hypotension, apnea).

3. Dislodged packing.

4. Aspiration.

5 . Persistent bleeding.

6. Infection, toxic shock syndrome.

7. Hypoxia resulting from nasal obstruction-may result in myocardial infarction, disorientation.

Most complications can be avoided if anticipated. Firm and gentle packing

avoids excessive nasal mucosal trauma. Sedation is kept to the minimum necessary to decrease aspiration risk and respiratory suppression. Oxygen should be

given when there are no contraindications. All patients receive prophylactic

antibiotics.

Toxic shock syndrome occurring with nasal packing can cause significant

morbidity and mortality. More than one third of patients undergoing nasal

packing are Staphylococcus aureus carriers. Comparison of NuGauze packs to

Merocel packs removed from patients noses revealed NuGauze grew out sub. ~ may occur because Merocel is a single homogestantially more s. a ~ r e u s This

neous structure, whereas NuGauze packing has interstices and folds of varying

sizes that more readily pool secretions. Toxic shock syndrome begins with fever,

vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, and body rash secondary to the production of

TSST-1, the primary toxin causing toxic shock syndrome. S. aureus is often

sensitive to bacitracin, so use of this intranasally can help prevent toxic shock

syndrome. Oxytetracycline and polymyxin B can also decrease the number of

bacterial strains cultured from packing used for nasal packs.

Interventions

Surgery

Endoscopic Cauterization. Endoscopes have revolutionized sinonasal surgery over the past two decades. In the management of epistaxis, use of the

52

TAN & CALHOUN

endoscope can permit identification of posterior bleeding sites, which can then

be directly cauterized, avoiding packing.12,51 It is especially useful in patients

who continue to bleed through well-placed nasal packs.

For these patients, the packings are usually removed when the patient is

under general anesthesia. The nasal cavity is cleansed and endoscopically examined. Common bleeding sites include the region of distribution of the sphenopalatine artery, posterior end of inferior turbinate, posterior-inferior septum, and

anterior sphenoid face. The suction electrocautery is useful. In the rare cases in

which no bleeding sites are located, Merocel packs are placed for 48 hours.

The authors have been using endoscopic examination in the outpatient

setting with selected patients. Using good topical anesthesia and mild sedation

and a suction/electrocautery unit, some more posteriorly placed bleeding points

can be identified and cauterized with minimal patient discomfort. Many of these

patients would traditionally have required nasal packing and hospitalization, so

avoidance of this is popular with both patients and managed care companies.

Arterial Ligation. Arterial ligation decreases arterial blood flow to the

bleeding area. Commonly ligated supplying branches include the internal maxillary artery (terminating as the sphenopalatine artery) and the anterior ethmoidal

artery. Ligation of the external carotid artery is also possible, although uncommonly needed.

Posterior epistaxis is usually supplied by the terminal branches of the

internal maxillary artery. The third part of the internal maxillary artery courses

behind the maxillary antrum to the sphenopalatine foramen at the superomedial

sinus. As the internal maxillary artery exits the sphenopalative foramen, it

divides into medial (to the sphenoid/septum) and lateral (lateral nasal wall)

divisions. The transantral (via the maxillary antrum) approach allows ligation

just before the terminal branching. Traditionally the transantral approach involved the removal of anterior wall of the maxillary sinus (Caldwell Luc) for

surgical access.hThe microscope is used for dissection behind the posterior wall

of the antrum. The endoscope has provided an alternative approach with less

morbidity, although it is technically more difficult (Fig. 2).68

Ethmoidal arterial ligation is performed when bleeding arises in the superior nose (above the middle turbinate). Ethmoidal artery ligation uses a curved

incision around the medial canthus. The globe is retracted away from the lamina

papyracea, and the anterior ethmoidal artery is encountered about 24 mm from

the anterior lacrimal crest. The vessels are clipped and ligated under direct

vision. Patients with intractable epistaxis without an identifiable bleeding point

may benefit from ligation of both the anterior ethmoidal artery and the internal

maxillary artery.

Embolization. An alternative to surgical ligation is embolization of external

carotid artery branches.", 26, 58 This procedure is particularly useful in patients at

high risk for a general anesthetic or with unfavorable anatomy (small maxillary

antra).47Embolization is successful in up to 96% of cases, although vascular

anatomic variations limit application in some cases. One benefit of embolization

over arterial ligation is that more selective blockade of smaller branches is possible.

Complications of embolization include up to 6% of neurologic sequelae. The

risk of particulate material embolization to the internal carotid systems has been

minimized by the current use of microcoils.13

Blood Transfusion

With the risk of disease transmission through blood products increasing,

epistaxis is treated to minimize the need for transfusion. Nasal packing has been

EPISTAXIS

53

Figure 2. A, Endoscopic view of the posterior wall of a left maxillary sinus that has been

opened showing the internal maxillary artery ligated by clips. B,Schematic diagram of A.

the first-line treatment of patients whose bleeding cannot be managed on an

outpatient basis. Packing provides a tamponade and encourages thrombosis of

vessels. There have been signs of this shifting toward early and prophylactic

One study compared the cost of hospitalization with nasal packing to hospitalization with surgical intervention and reported a higher cost and

complication rate with surgical intervention. These patients, however, received

surgical intervention only after failing nasal packing. There was a 27% transfusion rate (3 units per patient) with nasal packing compared with 41% (5.8 units

per patient) with nasal packing failure and subsequent surgery. Another study

also noted a greater transfusion requirement with surgical intervention than

without (0.91 units versus 2.93 units, P<.01).53These authors suggest that pa-

54

TAN & CALHOUN

tients requiring more than 3 units of blood should be considered for surgical

intervention. The cost a n d risk of surgical intervention m u s t be weighed against

the risks of transfusion a n d compromised cardiovascular status if rebleeding occurs.

Dealing with a patient w i t h active severe epistaxis can be bloody. The

authors recommend universal precautions for all health care personnel involved

in the care of these patients, including face mask with shields, gowns, hair

coverage, a n d double-gloving.

SUMMARY

Epistaxis is a common clinical problem. The widespread availability of

endoscopic equipment is shifting management philosophy toward targeting the

bleeding point. This shift may have a significant impact on decreasing length of

stay a n d blood transfusion rates. Advances i n interventional radiology have also

reduced the risk of embolization. Patient education, especially teaching first-aid

measures to patients a t high risk for nosebleeds, also encourages more effective

use of health care resources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Carol Chan for her assistance with the illustrations.

References

1. Adler D, Ritz E: Perforation of the nasal septum in patients with renal failure. Laryngo-

scope 90:317-321, 1980

2. Akama H, Hama N, Amano K: Epistaxis induced by a non-steriodal anti-inflammatory

drug? J R SOCMed 83:538,1990

3. Breda SD, Jacobs JB, Lebowitz AS, et al: Toxic shock syndrome in nasal surgery: A

physiochemical and microbiologic evaluation of Merocel and NuGauze nasal packing.

Laryngoscope 97:1388-1391,1987

4. Carr ME, Gabriel DA: Nasal packing with porcine fatty tissue for epistaxis complicated

by qualitative platelet disorders. J Emerg Med 3449452, 1985

5. Cassisi NJ, Biller HF, Ogura JH: Changes in arterial oxygen tension and pulmonary

mechanics with the use of posterior packing in epistaxis: A preliminary report. Laryngoscope 81:1261-1266, 1971

6 . Chandler JR, Serrins AJ: Transantral ligation of the internal maxillary artery for epistaxis. Laryngoscope 75:1151-1159, 1965

7. Corbridge RJ, qazaeri B, Hellier WP, et al: A prospective randomised controlled trial

comparing the use of Merocel nasal tampons and BIPP in the control of acute epistaxis.

Clin Otolaryngol 20:305-307, 1995

8. Culbertson MC, Manning SC: Epistaxis. In Bluestone CD, Stool SE (eds): Pediatric

Otolaryngology, ed 2. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1990

9. Dhillons RS, East CA: Ear, Nose and Throat and Head and Neck Surgery. London,

Churchill Livingstone, 1994

10. Ducic Y, Brownrigg P, Laughlin S Treatment of haemorrhagic telangiectasia with

flashlamp-pulsed dye laser. J Otolaryngol 24299-302, 1995

11. Elahi MM, Parnes LS, Fox AJ, et al: Therapeutic embolisation in the treatment of

intractable epistaxis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 121:65-69, 1995

12. Elwany S, Abdel-Fatah H: Endoscopic control of posterior epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol

110:432434, 1996

13. Ernst RJ, Bulas RV, Gaskill-Shipley M, et al: Endovascular therapy of intractable

EPISTAXIS

55

epistaxis complicated by carotid artery occlusive disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol

1611463-1468, 1995

14. Garth RJN, Cox HJ, Thomas MR Haemorrhage as a complication of inferior turbinectomy: A comparison of anterior and radical trimming. Clin Otolaryngol 20:236238, 1995

15. Glatt AE, Anand A: Thrombocytopenia in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: Treatment update. Clin Infect Dis 21:415423, 1995

16. Green A, Smallman LA, Logan ACM, et al: The effect of temperature on nasal ciliary

beat frequency. Clin Otolaryngol20:178-180, 1995

17. Haitjema T, Balder W, Disch FJ, et al: Epistaxis in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Rhinology 34:176-178, 1996

18. Hara HJ: Severe epistaxis. Arch Otolaryngol 75:84-95, 1962

19. Herzon FS: Bacteremia and local infections with nasal packing. Arch Otolaryngol

94317-320, 1971

20. Hicks JN, Norris J W Office treatment by cryotherapy for severe posterior nasal

epistaxis-update. Laryngoscope 93:876-879, 1983

21. Ibrahim NM, Cheong I: Adult dengue haemorrhagic fever at Kuala Lumpur Hospital:

A retrospective study of 102 cases. Br J Clin Pract 49:189-191, 1995

22. Idupuganti S: Epistaxis in hypertensive patient taking thioridazine. Am J Pyschiatry

139:1083-1084, 1982

23. Jackson KR, Jackson RT Factors associated with active, refractory epistaxis. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 114:862-865, 1988

24. Jeal W, Faulds D: Triamcinolone acetonide: A review of its pharmacololgical properties

and therapeutic efficacy in the management of allergic rhinitis. Drugs 53:257-280, 1997

25. Juselius H: Epistaxis: A clinical study of 1724 patients. J Laryngol Otol88:317-327,1974

26. Klein GE, Kole W, Karaic R, et a1 Endovascular embolization treatment for intractable

epistaxis. Laryngorhinootologie 76:83-87, 1997

27. Kotecha B, Fowler S, Harkness P, et al: Management of epistaxis: A national survey.

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 78:444446, 1996

28. Krempl GA, Noorily AD: Use of oxymetazoline in the management of epistaxis. AM

Otol Rhinol Laryngol 104(9 pt 1):704-706, 1995

29. Kushner FH: Sodium chloride eye drops as a cause of epistaxis. Arch Ophthalmol

105:1634, 1987

30. Lavy J: Epistaxis in anticoagulated patients: Educating an at risk population. Br J

Haematol 95:195-197, 1996

31. Lavy JA, Koay CB: First aid treatment of epistaxis-are patients well informed? J

Accid Emerg Med 13:193-195, 1996

32. Lethagen S, Ragnarson Tennvall G: Self-treatment with desmopressin intranasal spray

in patients with bleeding disorders: Effect on bleeding symptoms and socioeconomic

factors. AM Hematol 66:257-260, 1993

33. Livesey JR, Watson MG, Kelly PJ, et al: Do patients with epistaxis have drug-induced

platelet dysfunction? Clin Otolaryngol 20:407-410, 1995

34. Lucente FE: Thanthology: A study of 100 deaths. Trans Acad Ophthalmol Otol76:334339, 1972

35. Ludman H: ABC of Otolaryngology, ed 3. London, BMJ Publishers, 1993

36. McGarry G W Drug induced epistaxis? J R SOCMed 83:812, 1990

37. McGarry GW, Gatehouse S, Verham G: Idiopathic epistaxis, haemostasis and alcohol.

Clin Otolaryngol 20:174-177, 1995

38. McGarry GW, Moulton C: Epistaxis first aid. Arch Emerg Med 10:298-300, 1993

39. McGlashan JA, Walsh R, Dauod A, et al: A comparative study of calcium sodium

alginate (Kaltostat) and bismuth tribromophenate (Xeroform) packing in the management of epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol 106:1067-1071, 1992

40. Milam SB, Cooper RL Extensive bleeding following extractions in a patient undergoing

chronic hemodialysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 55:14, 1983

41. Mitchell JRA: Nose bleeding and high blood pressure. BMJ 1:25-27, 1959

42. Mittleman M, Ogarten U, Lewinski U, et al: Dipyridamole-induced epistaxis. AM Otol

Rhinol Laryngol 95:302-303, 1986

56

TAN & CALHOUN

43. Murray AB, Milner RA: Allergic rhinitis and recurrent epistaxis in children. Ann

Allergy Asthma Immunol 74:30-33, 1995

44. Okafor BC: Epistaxis: A clinical study of 540 cases. Ear Nose Throat J 63:153-159, 1984

45. Ong CC, Pate1 KS: A study comparing rates of deflation of nasal balloons used in

epistaxis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 50:33-35, 1996

46. OReilly BJ, Simpson DC, Dharmeratnam R Recurrent epistaxis and nasal septa1

deviation in young adults. Clin Otolaryngol 21:12-14, 1996

47. Pearson BW, Mackenzie RG, Goodman WS: The anatomical basis of transantral ligation

of the maxillary artery in severe epistaxis. Laryngoscope 79:969-984, 1969

48. Pringle MB, Beasley P, Brightwell AP: The use of Merocel nasal packs in the treatment

of epistaxis. J Laryngol Otol 110:543-546, 1996

49. Rebeiz EE, Byran DJ, Ehrlichmann RJ, et al: Surgical management of life-threatening

epistaxis in Osler-Weber-Rendu disease. Ann Plast Surg 35:208-213, 1995

50. Renuad S, Lorgeril M de: Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary

heart disease. Lancet 339:1523-1526, 1992

51. Rudert H, Maune S Endonasal coagulation of the sphenopalatine artery in severe

posterior epistaxis. Laryngorhinootologie 76:77-82, 1997

52. Schiatkin B, Strauss M, Houck J R Epistaxis: Medical versus surgical therapy: A

comparison of efficacy, complications, and economic considerations. Laryngoscope

971392-1396, 1987

53. Shaw CB, Wax MK, Wetmore SJ: Epistaxis: A comparion of treatment. Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg 109:60-65, 1993

54. Simpson HK, Baird J, Allison M, et al: Long-term use of low molecular weight heparin

tinzaparin in haemodialysis. Haemostasis 26:90-97, 1996

55. Stangerup SE, Dommerby H, Lau T Hot-water irrigation as a treatment of posterior

epistaxis. Rhinology 34:18-20, 1996

56. Stangerup SE, Thomsen U K Histological changes in the nasal mucosa after hot-water

irrigation: An animal study. Rhinology 34:14-17, 1996

57. Stine KC, Becton DL: DDAVP therapy controls bleeding in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J

Pediatr Haematol Oncol 19:156-158, 1997

58. Strong EB, Bell DA, Johnson LP, et al: Intractable epistaxis: Transantral ligation vs

embolization: Efficacy review and cost analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113:674

678, 1995

59. Sugarman PM, Alderson DJ: Training model for nasal packing. J Accid Emerg Med

12:276-278, 1995

60. Taylor MT Avitene-its value in the control of epistaxis. J Otolaryngol9:466471, 1980

61. Tomkinson A, Bremmer-Smith A, Craven C, et al: Hospital epistaxis admission rate

and ambient temperature. Clin Otolaryngol 20:239-240, 1995

62. Turner P: The swimmers nose clip in epistaxis. J Accid Emerg Med 13:134, 1996

63. Vickery CL, Kuhn FA: Using the KTP/532 laser to control epistaxis in patients with

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. South Med J 89:78-80, 1996

64. Viduich RA, Blanda MP, Gerson LW: Posterior epistaxis: Clinical features and acute

complications. Ann Emerg Med 25:592-596, 1995

65. Wantke F, Focke M, Hemmer W, et al: Formaldehyde and phenol exposure during an

anatomy dissection course: A possible source of -1gE-mediated sen&tization. Allergy

51:837-841, 1996

66. Watson MG, Shenoi PM: Drug induced epistaxis? J R SOCMed 83:162-164, 1990

67. Weiss NS: Relation of high blood pressure to headache, epistaxis, and selected other

symptoms. N Engl J Med 287631-633, 1972

68. Winstead W Sphenopalatine artery ligation: An alternative to internal maxillary artery

ligation for intractable posterior epistaxis. Laryngoscope 106(5 pt 1):667-669, 1996

Address reprint requests to

Karen H. Calhoun, MD

Department of Otolaryngology

University of Texas Medical Branch

Galveston. TX 77555-0521

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Medicine in Brief: Name the Disease in Haiku, Tanka and ArtVon EverandMedicine in Brief: Name the Disease in Haiku, Tanka and ArtBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Epistaxis: Neil Alexander Krulewitz,, Megan Leigh FixDokument11 SeitenEpistaxis: Neil Alexander Krulewitz,, Megan Leigh FixSantos Pardo GómezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpreting Bravo PH StudiesDokument16 SeitenInterpreting Bravo PH StudiesLilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- EHEDG Guidelines by Topics 04 2013Dokument2 SeitenEHEDG Guidelines by Topics 04 2013renzolonardi100% (1)

- CHAPTER 8 f4 KSSMDokument19 SeitenCHAPTER 8 f4 KSSMEtty Saad0% (1)

- AluminumPresentationIEEE (CompatibilityMode)Dokument31 SeitenAluminumPresentationIEEE (CompatibilityMode)A. HassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tan1999 PDFDokument14 SeitenTan1999 PDFIntan Nur HijrinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cumming - Otolaryngology - EpistaxisDokument9 SeitenCumming - Otolaryngology - EpistaxisPro fatherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approach To The Adult With Epistaxis - UpToDateDokument29 SeitenApproach To The Adult With Epistaxis - UpToDateAntonella Angulo CruzadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- EpistaxisDokument12 SeitenEpistaxisalputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epistaxis: A Common Problem: Adil Fatakia, MD, Ryan Winters, MD, Ronald G. Amedee, MDDokument3 SeitenEpistaxis: A Common Problem: Adil Fatakia, MD, Ryan Winters, MD, Ronald G. Amedee, MDaprilfitriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approach To The Adult With EpistaxisDokument18 SeitenApproach To The Adult With EpistaxisTP RMad100% (1)

- S Infective EndocarditisDokument24 SeitenS Infective EndocarditisMpanso Ahmad AlhijjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Updates On The Management of Epistaxis: ReviewDokument11 SeitenUpdates On The Management of Epistaxis: ReviewBagusPranataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infective Endocarditis WORDDokument24 SeitenInfective Endocarditis WORDHashmithaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EpistaxisDokument9 SeitenEpistaxisAswathy RCNoch keine Bewertungen

- EpistaxisDokument39 SeitenEpistaxisAbubakar JallohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mona Notes - NoseDokument11 SeitenMona Notes - NoseBinta BaptisteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anterior Epistaxis PDFDokument9 SeitenAnterior Epistaxis PDFTiara Audina DarmawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epistaxis Pic 2014 01 GDokument70 SeitenEpistaxis Pic 2014 01 GJeanne d'Arc DyanchanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epistaxis 2-1-6Dokument6 SeitenEpistaxis 2-1-6Nurul aina MardhiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- 18 Infective EndocarditisDokument15 Seiten18 Infective EndocarditisCabdiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Postgrad Med J 2005 Pope 309 14Dokument9 SeitenPostgrad Med J 2005 Pope 309 14Steven LiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EndocarditisDokument53 SeitenEndocarditisمحمد ربيعيNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infective Endocarditis: Pathology and PathogenesisDokument6 SeitenInfective Endocarditis: Pathology and PathogenesisPeace ManNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infective EndocarditisDokument13 SeitenInfective EndocarditisIbrahimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal EpistaksisDokument8 SeitenJurnal Epistaksiskhusna wahyuniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epistaxis: Dr. Wachuka G. Thuku Tutorial Fellow-ENT RegistrarDokument32 SeitenEpistaxis: Dr. Wachuka G. Thuku Tutorial Fellow-ENT RegistrarAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- EpistaxisDokument30 SeitenEpistaxisAhlam DreamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeDokument17 SeitenAcute Respiratory Distress SyndromeSanjeet Sah100% (1)

- Epistaxis: Clinical PracticeDokument8 SeitenEpistaxis: Clinical PracticebadrhashmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infective Endocarditis: History & ExamDokument75 SeitenInfective Endocarditis: History & ExamMicija CucuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complications During HemodialysisDokument2 SeitenComplications During HemodialysisHelconJohn100% (1)

- Critical Care (Emergency Medicine) : HemothoraxDokument7 SeitenCritical Care (Emergency Medicine) : HemothoraxOrlando PiñeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epistaxis AlgoritmoDokument13 SeitenEpistaxis AlgoritmocristobalchsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis: Clinical FeaturesDokument4 SeitenCavernous Sinus Thrombosis: Clinical FeaturesStefanus ChristianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDokument4 SeitenOsler-Weber-Rendu Disease - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epistaxis: Prevailing Factor and Treatment: Dr. H. Oscar Djauhari, SP - THTDokument19 SeitenEpistaxis: Prevailing Factor and Treatment: Dr. H. Oscar Djauhari, SP - THTAbi NazhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- SplitPDFFile 601 To 800Dokument200 SeitenSplitPDFFile 601 To 800Shafan ShajahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric Fungal EndocarditisDokument9 SeitenPediatric Fungal EndocarditisGuntur Marganing Adi NugrohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case StudyDokument10 SeitenCase StudyAnnisa Trihandayani100% (2)

- Dialysis: Muath Alismail Reviewed With: Dr. MunirDokument33 SeitenDialysis: Muath Alismail Reviewed With: Dr. MunirMuath ASNoch keine Bewertungen

- DHA EXAM Mcq-1.PdfhhhhlllDokument56 SeitenDHA EXAM Mcq-1.PdfhhhhlllSajid Rashid100% (5)

- Die (20 Versus 12 Percent) Experience An Embolic Event (60 Versus 31 Percent) Have A CNS Event (20 Versus 13 Percent) Not Undergo Surgery (26 Versus 39 PercentDokument37 SeitenDie (20 Versus 12 Percent) Experience An Embolic Event (60 Versus 31 Percent) Have A CNS Event (20 Versus 13 Percent) Not Undergo Surgery (26 Versus 39 Percentnathan asfahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shock 20231122 213304 0000Dokument32 SeitenShock 20231122 213304 0000Mikella E. PAGNAMITANNoch keine Bewertungen

- DengueDokument65 SeitenDengueShajahan SideequeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6.infective EndocarditisDokument62 Seiten6.infective Endocarditisbereket gashuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 - RH Fev, Inf EndoDokument37 Seiten2 - RH Fev, Inf EndoLobna ElkilanyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aureus or Escherichia Coli. Less Typically, Polymicrobial Abscesses Have Been NotedDokument7 SeitenAureus or Escherichia Coli. Less Typically, Polymicrobial Abscesses Have Been NotedDiana MinzatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Massive Hemoptysis: Resident Grand RoundsDokument7 SeitenMassive Hemoptysis: Resident Grand RoundsEko CahyonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Pakai 3 (Etiologi) Efusi PerikardiumDokument10 SeitenJurnal Pakai 3 (Etiologi) Efusi PerikardiumSatrya DitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PJT Cvcu Bed 4 Acute Limb IschemicDokument33 SeitenPJT Cvcu Bed 4 Acute Limb IschemicHabibie El RamadhaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Background: EmbryologyDokument25 SeitenBackground: EmbryologydonisaputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Referat SepsisDokument18 SeitenReferat SepsisImelva GirsangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ug Infective Endocarditis SubmitDokument49 SeitenUg Infective Endocarditis SubmitAhmed FaizalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Nursing (III)Dokument32 SeitenSurgical Nursing (III)Opio MosesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis: Key PointsDokument22 SeitenCavernous Sinus Thrombosis: Key PointsAmirul Ashraf Bin ShukeriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lo No 1 Epistaksis - Id.enDokument17 SeitenLo No 1 Epistaksis - Id.enRezi OktavianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- EPISTAXIS LectureDokument30 SeitenEPISTAXIS LectureDhienWhieNoch keine Bewertungen

- ArdsDokument69 SeitenArdsdrabdallakawareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesth Analg 2010 Elliott 1419 27Dokument9 SeitenAnesth Analg 2010 Elliott 1419 27Darrel Allan MandiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2007 J. Emergencies ENT PubmedDokument7 Seiten2007 J. Emergencies ENT PubmedRio SanjayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulmonary Edema - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDokument7 SeitenPulmonary Edema - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfriyanasirNoch keine Bewertungen

- PR Dr. AriadneDokument8 SeitenPR Dr. AriadneSofia KusumadewiNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Today Vol.1 Varianta 2 PDFDokument93 SeitenEnglish Today Vol.1 Varianta 2 PDFDan CelacNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2007, Vol.40, Issues 5, The Professional VoiceDokument269 Seiten2007, Vol.40, Issues 5, The Professional VoiceLamia Bohliga100% (1)

- Videostroboscopy in Laryngopharengeal RefluxDokument5 SeitenVideostroboscopy in Laryngopharengeal RefluxLilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 GERD Abstractbook 11FINAL 67833Dokument174 Seiten0 GERD Abstractbook 11FINAL 67833Lilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laryngopharyngeal Reflux, DR A HaddadDokument35 SeitenLaryngopharyngeal Reflux, DR A HaddadLilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0003489414532777Dokument10 Seiten0003489414532777Lilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abnormal Endoscopic Pharyngeal and LaryngealDokument7 SeitenAbnormal Endoscopic Pharyngeal and LaryngealLilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Campaign 1 - English For The Military StudentDokument160 SeitenCampaign 1 - English For The Military StudentLilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Posterior Commissure of The Human Larynx Revisited PDFDokument8 SeitenPosterior Commissure of The Human Larynx Revisited PDFLilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sulcus Vocalis 20070808Dokument38 SeitenSulcus Vocalis 20070808Lilia ScutelnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content of An Investigational New Drug Application (IND)Dokument13 SeitenContent of An Investigational New Drug Application (IND)Prathamesh MaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uppercut MagazineDokument12 SeitenUppercut MagazineChris Finn100% (1)

- Immobilization of E. Coli Expressing Bacillus Pumilus CynD in Three Organic Polymer MatricesDokument23 SeitenImmobilization of E. Coli Expressing Bacillus Pumilus CynD in Three Organic Polymer MatricesLUIS CARLOS ROMERO ZAPATANoch keine Bewertungen

- Ural Evelopment: 9 9 Rural DevelopmentDokument17 SeitenUral Evelopment: 9 9 Rural DevelopmentDivyanshu BaraiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 365 Days (Blanka Lipińska)Dokument218 Seiten365 Days (Blanka Lipińska)rjalkiewiczNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 14 Revision Guide Organic SynthesisDokument6 Seiten3 14 Revision Guide Organic SynthesisCin D NgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Case History FDokument6 SeitenChild Case History FSubhas RoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soft Tissue SarcomaDokument19 SeitenSoft Tissue SarcomaEkvanDanangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Docu Ifps Users Manual LatestDokument488 SeitenDocu Ifps Users Manual LatestLazar IvkovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geometry of N-BenzylideneanilineDokument5 SeitenGeometry of N-BenzylideneanilineTheo DianiarikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hema Lec HematopoiesisDokument8 SeitenHema Lec HematopoiesisWayne ErumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan On Tuberculosis (Health Talk)Dokument8 SeitenLesson Plan On Tuberculosis (Health Talk)Priyanka Jangra100% (2)

- POB Ch08Dokument28 SeitenPOB Ch08Anjum MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 10 - Reinforced - Concrete - Fundamentals and Design ExamplesDokument143 SeitenCH 10 - Reinforced - Concrete - Fundamentals and Design ExamplesVeronica Sebastian EspinozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alternative ObligationsDokument42 SeitenAlternative ObligationsJanella Gail FerrerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minerals and Resources of IndiaDokument11 SeitenMinerals and Resources of Indiapartha100% (1)

- AUDCISE Unit 1 WorksheetsDokument2 SeitenAUDCISE Unit 1 WorksheetsMarjet Cis QuintanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learning Activity Sheet MAPEH 10 (P.E.) : First Quarter/Week 1Dokument4 SeitenLearning Activity Sheet MAPEH 10 (P.E.) : First Quarter/Week 1Catherine DubalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 SMDokument10 Seiten1 SMAnindita GaluhNoch keine Bewertungen

- BT HandoutsDokument4 SeitenBT HandoutsNerinel CoronadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trillanes V PimentelDokument2 SeitenTrillanes V PimentelKirk LabowskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence-Based Strength & HypertrophyDokument6 SeitenEvidence-Based Strength & HypertrophyAnže BenkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transmission Lines SMART EDGE VILLARUEL For April 2024 v1Dokument89 SeitenTransmission Lines SMART EDGE VILLARUEL For April 2024 v1mayandichoso24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Precision Medicine Care in ADHD The Case For Neural Excitation and InhibitionDokument12 SeitenPrecision Medicine Care in ADHD The Case For Neural Excitation and InhibitionDaria DanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- KL 4 Unit 6 TestDokument3 SeitenKL 4 Unit 6 TestMaciej Koififg0% (1)

- Women and International Human Rights Law PDFDokument67 SeitenWomen and International Human Rights Law PDFakilasriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Photosynthesis PastPaper QuestionsDokument24 SeitenPhotosynthesis PastPaper QuestionsEva SugarNoch keine Bewertungen