Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Barriers To Health Promotion in Community Dwelling Elders

Hochgeladen von

Kusrini Kadar SyamsalamOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Barriers To Health Promotion in Community Dwelling Elders

Hochgeladen von

Kusrini Kadar SyamsalamCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by: [Monash University Library]

On: 20 September 2012, At: 19:55

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Community Health Nursing

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hchn20

Barriers to Health Promotion in

Community Dwelling Elders

a

Mary Ann Stark , Carla Chase & Alice DeYoung

Bronson School of Nursing, Western Michigan University,

Kalamazoo, Michigan

b

Occupational Therapy Program, Western Michigan University,

Kalamazoo, Michigan

Version of record first published: 06 Nov 2010.

To cite this article: Mary Ann Stark, Carla Chase & Alice DeYoung (2010): Barriers to Health Promotion

in Community Dwelling Elders, Journal of Community Health Nursing, 27:4, 175-186

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07370016.2010.515451

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation

that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any

instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary

sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or

indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Journal of Community Health Nursing, 27:175186, 2010

Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0737-0016 print/1532-7655 online

DOI: 10.1080/07370016.2010.515451

Barriers to Health Promotion

in Community Dwelling Elders

Mary Ann Stark

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

Bronson School of Nursing, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan

Carla Chase

Occupational Therapy Program, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan

Alice DeYoung

Bronson School of Nursing, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan

As the number of elders who live in the community increases, promoting their health and independence is a priority of nursing care. As suggested in the Health Promotion Model, barriers can impede

the practice of health promotionn. In this descriptive correlational study, community-dwelling elders

65 and older were recruited (N=141) to examine the relationship between attentional demands as measured by the Attentional Demands Survey and health promotion. The results indicate that attentional

demands may act as barriers, reducing elders ability to engage in health promotion. Community

health nurses can focus care toward reducing attentional demands and improving health promotion.

As the baby boom generation (those born between 1941 and 1964) ages, the impact on communities and health care will be significant, as their need for care and services grows and brings dramatic changes in health care and in society (Young & Capezuti, 2010, p. 112). That trend continues as the first of this generation reaches 65 in January 2011, with the number of those 65 and

older steadily increasing from 35 million in 2000 to an anticipated peak of 71 million by 2030,

with the fastest growing segment being those over 85 years old (Center for Disease Control and

Prevention, 2003). Care at the home and community level will become even more important as the

healthcare system prepares for this silver tsunami. The benefits of keeping older adults healthy include their continued ability to participate and contribute to the life of the community, as well as

spending less on medical costs and long-term care (Young & Capezuti, 2010). In addition, the objectives that have been proposed for Healthy People 2020 reflect the importance of addressing the

needs of this generation, particularly in the area of health promotion. Increasing elders management of chronic health conditions, encouraging engagement in leisure-time physical activities,

and decreasing the risk of falls are all areas where health promotion may be beneficial (US Dept of

Health and Human Services, 2009).

Address correspondence to Dr. Mary Ann Stark, PhD, RNC, Associate Professor, Bronson School of Nursing, Western

Michigan University, 1903 W. Michigan Ave, Kalamazoo, MI 49008. E-mail:mary.stark@wmich.edu

176

STARK, CHASE, DEYOUNG

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

When exploring best practices for home and community health promotion, it is important to

consider the barriers to acceptance and compliance. Jansens (2006) work in attentional demands

and its impact on the functional status of community-dwelling elders indicates that those tasks that

require additional processing and more focused attention or concentration (higher attentional demands) may become more difficult with age and, thus, negatively impact the ability to manage

daily activities to their satisfaction. The purpose of this study was to examine the attentional demands that might act as barriers to the practice of health promoting behaviors in community

dwelling elders (65 and older).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The Health Promotion Model (HPM), which was developed with consideration of the multidimensional nature of persons and the unique environment in which each person functions, was the

framework that guided this research (Pender, Murdaugh, & Parsons, 2005). This model considers

factors that influence a persons practice of health promoting behaviors, defined as those activities

that attain positive health outcomes, improved health, or improved quality of life (Pender et al.,

2005). Physical activity, good nutrition, healthy interpersonal relationships, stress management

resources, spiritual growth, and a sense of personal health responsibility are attitudes and behaviors that promote health (Walker, Sechrist, & Pender, 1987). This model allows for examining factors associated with improved health promotion and allows focusing on personal and environmental factors that influence health promotion (Young & Capezuti, 2010).

In the HPM, individual characteristics (such as age, gender, and self-esteem) and previous behavior

are considered, as they are thought to influence whether an individual participates in health-promoting

behaviors (Pender et al., 2005). In addition, the HPM suggests that there are behavior-specific

cognitions and affect that influence motivation for specific health promoting behaviors. These factors

are ones that are often modifiable and subject to nursing intervention. Perceived barriers to action is another factor thought to influence health promoting behaviors and amenable to nursing interventions.

These barriers to action can be actual or perceived barriers, such as time, inconvenience, difficulty of

the behavior, and expenses as well as personal costs (Pender et al., 2005). When barriers are high and

readiness to act is low, health promoting behaviors are less likely (Pender et al., 2005).

One potential barrier to health-promoting behaviors may be attentional demands, which are

factors that can serve as distractions or competing stimuli to the ability to focus or direct attention.

The ability to focus, or pay attention, is important for daily activities, including health promotion,

and functioning and may be especially difficult in situations where there are distractions (Jansen,

2006; Stark & Cimprich, 2003). For the elderly, age-related changes and new life circumstances

can serve as attentional demands that may act to deter health-promoting behavior. Jansen and

Keller (1999) proposed that attentional demands be described within four domains. The first domain is physical-environmental, and includes external factors such as noise, poor lighting, and

weather (Jansen & Keller, 1999). Presence of stairs and poor building design may make navigating the environment difficult, and serve as a barrier to health-promoting activities. The second domain is informational, and includes factors that make perception and information processing difficult. Hearing and vision changes may make it difficult for a person to interact in some health

promotion activities such as attending an exercise class. The third domain is behavioral demands,

which are factors that interfere or restrict activities (Jansen & Keller, 1999). A sense of vulnerabil-

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

BARRIERS TO HEALTH PROMOTION

177

ity or changes in physical mobility may limit health promotion behaviors. Affective demands are

emotions, worries, or preoccupations that must be inhibited for daily functioning (Jansen &

Keller, 1999). Feelings of loss, loneliness, and worries about health or safety might interfere with

health promoting activities. Thus, attentional demands may be barriers (either perceived or actual)

to the practice of healthy behaviors for elderly persons. In research with elderly, community-dwelling women (65 and older), Jansen and Keller (2003) found that women who reported

more attentional demands also reported more depressive symptoms and poorer health than women

with fewer attentional demands. In a later study of elder men and women, those with fewer

attentional demands also reported better health than those with more attentional demands (Jansen,

2006). Although the presence of attentional demands is theoretically related to the practice of

health promoting behaviors in the HPM, empirical research supports that attentional demands are

related to health (Jansen, 2006; Jansen & Keller, 2003).

The effects of aging and the rate of change with age vary from person to person, however, there

are some general changes to be considered when exploring a relationship between attentional demands and health promotion. Physically, the body slows in its ability to react to changes in the environmentboth in quick responses to a challenge involving balance or movement and in slower

responses as when attempting to reach homeostasis following environmental temperature changes

(Kail & Cavanaugh, 2010; Ojha, Kem, Lin, & Winstein, 2009; Shumway-Cook & Woollacott,

2000). Cognitive changes can be described similarly in that fluid intelligence, which is the ability

to respond quickly to multiple stimuli and to problem-solve, slows down with age. On the other

hand, crystallized intelligence, which is stored knowledge gathered over a lifetime, does not decrease substantially in the absence of disease (Kail & Cavanaugh, 2010). The combination of

these normal age-related changes can lead to the need for more focused attention on tasks, especially more complicated ones such as driving. This higher attentional demand can reduce the ability to effectively multitask, can require greater energy expenditure overall, and may lead to a decrease in participation in some higher-level tasks, including health promoting behaviors. In this

way, attentional demands may act as barriers to health promotion.

The relationship between attentional demands and health promotion has not been explored in

community dwelling elders. If these barriers are amenable to interventions, elders might be more

inclined to practice health promotion. The research questions proposed for this study are: (a) Is

there a relationship between attentional demands and health promotion? And (b) Is there a difference between younger (6574 years old), older (7584 years old), and oldest (85 and older) elders

in their attentional demands?

METHODS

To address the research questions, a descriptive correlational survey design was used. Following

institutional review board approval from the university where we teach, a sample of community

dwelling elders was recruited from senior centers, churches, and community agencies. Signs were

posted in some sites, and a research assistant personally attended some senior groups to invite participation. Anyone who was interested was given a packet that included a consent document, three

research questionnaires, and a postage-paid addressed envelope. If the participant consented to

participate, the participant could complete the questionnaires and return them via the postal service. Data were collected between May and July 2008 in a county in southwest Michigan.

178

STARK, CHASE, DEYOUNG

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

A sample of elders (65 and older) that lived independently in the community was recruited. Although many elders live in the community, their ability to navigate and participate in the community may be deterred by barriers they encounter. Health promotion is vital to maintaining their independence. Thus, community-dwelling elders were the population of interest. The researchers

invited anyone who was age 65 or older and could read, write, and understand English to participate if they were at one of the recruitment sites and lived independently. The final sample included

141 elders, with 46.1% of the sample (n=65) age 65 to 74, 38.3% (n=54) age 74 to 85, and 15.6%

(n=22) age 85 and older. The sample was mostly female, White, educated; most were not employed but did volunteer (see Table 1).

TABLE 1

Description of Sample

Gender

Male

Female

Race

Caucasian

African American

Latino

Marital status

Married

Widowed

Never married

Divorced

Residence

Apartment

House

Number of others in residence

Lives alone

One other person

Two or more

Highest education

Grammar school

Some high school

Graduated high school

Some college

Graduated college

Employed

Employed

Not employed

Volunteer

Yes

No

Age

Hr worked per week

Hr volunteer per week

Hr per week in other activities

49

92

34.8

65.2

139

1

1

98.6

.7

.7

84

42

4

11

59.6

29.8

2.8

7.8

20

121

14.2

85.8

52

82

6

31.6

58.2

4.3

1

7

38

37

58

.7

5.0

27.0

26.2

41.1

12

129

8.5

91.5

96

44

68.1

31.2

Mean

SD

Range

76.1

20.8

5.4

2.9

7.2

15.9

4.2

2.2

6594

3.550

.2520

015

BARRIERS TO HEALTH PROMOTION

179

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

Instruments

The two major concepts of interest to this study were health promotion and attentional demands that

may serve as barriers to the practice of health promotion. Three research measures were used for this

study. The first instrument was the Health Promoting Lifestyles Profile II (HPLP II; Walker, et al.,

1987) that was developed to measure the components of a healthy lifestyle (Pender, Murdaugh, &

Parsons, 2001). This instrument has demonstrated content, construct, and criterion-related validity

(Walker & Hill-Polerecky, 1996). The 52-item tool contains statements regarding behaviors used to

promote health to which the respondent is instructed to indicate one of four descriptors (never, sometimes, often, and routinely). The mean of all items was calculated for an overall HPLP II score, as directed by the HPLP II authors. In addition, six subscales were calculated by finding the mean of the

items of that subscale (Walker et al., 1987). The subscales were health responsibility (HR), physical

activity (PA), nutrition (NUTR), spiritual growth (SG), interpersonal relations (IPR), and stress

management (SM). For all scales, a higher score indicates greater health promotion; possible scores

ranged from 1 to 4. When reliability was tested, the HPLPII had testretest stability after 3 weeks

and internal consistency (Walker & Hill-Polerecky, 1996). For this sample, internal consistency, as

measured by Cronbachs alpha for the HPLPII, was .95. The Cronbachs alpha for the subscales

were .83 (HR), .87 (PA), .85 (NUTR), .86 (SG), .82 (IPR), and .76 (SM).

The second instrument used for this study was the Attentional Demands Survey (ADS) that

was developed to measure elders attentional demands, factors in daily living that require mental

effort to negotiate (Jansen & Keller, 1999). If many attentional demands are encountered, the elder

is more prone to mental fatigue and ineffective functioning in daily life. The ADS has four domains with corresponding scales, physical-environmental (PE), informational (INF), behavioral

(BEH), and affective (AF). The 42 item ADS listed demands that elders might encounter and asks

that they indicate effort required for this demand on a five point scale (not at all=0; somewhat =2;

a lot=4). Items in the individual scales were summed according to instructions; higher scores indicated more demands (Jansen & Keller, 1999). In this sample, the total ADS (sum of all items) had

a Cronbachs alpha of .96. Internal consistency computed by Cronbachs alpha for the individual

scales was .90 (PE), .91 (INF), .84 (BEH), and .88 (AF).

The third research instrument was a demographics questionnaire that we developed for the

study. Age, gender, employment status, and volunteer work are examples of items included in this

tool.

Data Analysis

Data were entered into SPSS 16.0 and cleaned. Descriptive statistics were determined for all variables of interest; scales were computed. Appropriate nonparametric and parametric tests of association were run as determined by the research questions. An alpha of .05 was determined a prior.

RESULTS

The first research question asked whether there was a relationship between attentional demands

(ADS) and health promotion (HPLPII). There was a moderate negative correlation between

HPLPII and the total ADS scale (r= .48, p=.000). A negative correlation was found between

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

180

STARK, CHASE, DEYOUNG

HPLPII and each of the four ADS scales (physical-environmental r= .42, p=.000; informational

r= .47. p=.000; behavioral r= .39, p=.00; affective r= .40, p=000). Elders who perceived more

attentional demands also had fewer health promoting behaviors.

The second research question asked whether there were differences between three age groups

in their perception of attentional demands. Means were calculated for ADS for each age group

(see Table 2). To test whether the differences were significant, one-way ANOVA was computed

for each of the ADS scales and the total ADS score. There was a significant difference on the total

ADS between the 6574 age group and the 7584 age group, but no difference between the oldest

group (85 and older) and either of the two younger groups (F=3.72, df=2,136, p=.027) when

Bonferroni post hoc tests were performed. The 75- to 84-year-olds had the highest attentional demands as measured by ADS and the 65- to 74-year-olds had the least. In addition, there were significant differences in informational (F=4.62, df=2,137, p=.011) and behavioral (F=3.36, df=2,

137, p=.038) scales between these two age groups, similar to that observed on the total ADS (see

Table 2). On all ADS scales, the 75- to 84-year-olds had higher means than the younger age group

(6574); the 75- to 84-age-year-old group reported more attentional demands than the younger

group (see Table 2). To determine the effect that the increased perception of attentional demands

might have on health promotion, the correlation between ADS and HPLPII was determined for

each age group (6574 year olds, r= .40, p=.001; 7584 year olds, r= .56, p=.000; 85 and older,

r= .55, p=.009) showing that attentional demands had a greater effect on the two older groups

than the youngest group.

To further explore the attentional demands of the three age groups, the means reported by each

group for each of the 42 items of the ADS were calculated and ranked. Items with higher means indicated the item created more effort in daily life. The top five items for each group are listed in

Table 3. The demands which the sample found least affected their daily functioning are listed in

Table 4. Not having enough light and having to move were demands that each age group identified

as problematic. Of particular interest is that for all age groups, managing medications required

very little effort for this sample of elders.

As attentional demands are thought to be amenable to nursing interventions (Jansen, 2006), relationships between demographic attributes of the group and the primary variables of interest in

this study were explored. There were no differences in ADS (t=.42, df=137, p=ns) or HPLP II

(t=.42, df=139, p=ns) when marital status was considered (married or currently single, which included never married, divorced, or widowed). In addition, there was no difference between men

and women on ADS (t=.76, df=137, p=ns) or HPLPII (t=1.42, df=121.72, p=ns). There was a

TABLE 2

Attentional Demands by Age Groups

Attentional Demands

Survey (ADS) Scale

Physical-environmental

Informational

Behavioral

Affective

Total ADS

6574 Age Group

(n=65)

7584 Age Group

(n=54)

85 and Older Age

Group (n=22)

SD

SD

SD

20.5

10.8

5.9

14.3

51.8

10.4

9.1

4.9

8.4

26.9

25.1

15.7

8.5

17.4

66.7

12.2

10.1

6.5

9.9

36.1

26.3

15.5

6.6

16.0

64.4

10.7

8.0

5.4

9.1

28.3

BARRIERS TO HEALTH PROMOTION

181

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

TABLE 3

Greatest Attentional Demands Reported by Age Groups

65 to 74 years of age

1. Not enough light

2. Uncomfortable or harsh weather conditions

3. Having to move

4. Missing family or friends who have died or live far away

5. Noise distractions

75 to 84 years of age

1. Uncomfortable or harsh weather conditions

2. Buildings that are hard to find your way around in

3. Not enough light

4. Having to move

5. Missing family or friends who have died or live far away

85 and older

1. Trouble hearing

2. Having to move

3. Bright sunlight and glare

4. Not enough light

5. Noise distractions

TABLE 4

Demands That Were Least Difficult by Age Groups

65 to 74 years of age

1. Managing medications

2. Going to the doctor or clinic or special appointment

3. Reading or responding to mail

75 to 84 years of age

1. Managing medications

2. Feeling sad about your present life situation

3. Not enough living space

85 and older

1. Being along or isolated

2. Managing medications

3. Other people do not listen or understand you

positive and weak but significant relationship between age and attentional demands (r=.24,

p=.005); age was not related to health promotion (r=.13, p=ns). As the sample was very homogenous on race, a relationship between race and attentional demands or health promotion could not

be explored. When those who had a high school education or less was compared to those who had

attended at least some college (or more), there was a significant difference on both the ADS

(t=2.29, df=137, p=.024) and HPLPII (t=4.21, df=139, p=.000). Those with more education perceived fewer attentional demands (M=55.25, SD=28.8) and had more health promoting behaviors

(M=2.94, SD=.45) than those with less education (ADS M=68.04, SD=35.2; HPLPII M=2.6,

SD=.46). Those who were employed (M=61.6, SD=31.5) had significantly lower ADS scores than

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

182

STARK, CHASE, DEYOUNG

those who were not employed (M=36.6, SD=21.4) (t=2.69, df=137, p=.008) although the number

working was small (see Table 1). There was no difference between those who were employed and

those who were not on HPLPII. On the other hand, those who volunteered had significantly higher

means on HPLPII (M=2.88, SD=.46) than those who did not (M=2.71, SD=.51; t=2.05, df=138,

p=.042). They also had lower ADS (M=56.06, SD=30.86) than those who did not volunteer

(M=66.19, SD=32.11; t=1.76, df=136, p=.080).

In summary, attentional demands were negatively and significantly associated with health promotion in this sample of community dwelling elders. There were significant differences among

age groups with elders 75 to 84 years old reporting significantly more attentional demands than

those in the younger group. Older groups reported more attentional demands than the younger

group of elders and this was associated with decreased health promotion.

DISCUSSION

The significant negative relationship between attentional demands and health-promoting lifestyle in elders is consistent with the HPM (Pender et al., 2005). With aging, elders have declining physical, social, and cognitive abilities that can serve as barriers to health promotion activities. On the ADS scale, this sample had higher scores on the total ADS scale than what was

reported in studies of other community dwelling elders indicating the presence of more

attentional demands (Jansen, 2006; Jansen & Keller, 2003). On only one of the scales (affective), did the current sample have a slightly lower score (15.8) than what Jansen and Keller

(2003) reported (15.9).

The HPM suggests that some personal demographic characteristics may influence health promotion behaviors. Consistent with what was reported by Jansen (2006), there was no relationship

between ADS and marital status. In this study, there was a weak but significant positive correlation between the ADS and age, which was not present in Jansens research. Elders in our study

who worked or volunteered had lower ADS scores than those who did not work or volunteer. Perceiving fewer attentional demands may make working and volunteering easier, in addition to encouraging health promoting behaviors.

A relationship between ADS and health has been reported. In previous studies, more attentional

demands were associated with poorer self-reported health and difficulty in daily functioning

(Jansen, 2006; Jansen & Keller, 2003). This can be explained by the HPM. As elders encounter

attentional demands that serve as barriers to health promoting behaviors, health may be impacted.

Although the sample in this study reported more attentional demands when compared to other

samples (Jansen, 2006; Jansen & Keller, 2003), they also reported more health-promoting behaviors when compared to other samples that included elders (Acton & Malathum, 2000; Callaghan,

2006; Lee, 2009). Age, marital status, and gender were not associated with health promoting behaviors in this sample of elders, as has been reported in other research (Acton & Malathum, 2000).

In another sample that included adults of a large age range (2179), employed adults had fewer

health promoting behaviors than those who were retired (Acton & Malathum, 2000). This was not

the case in this study of elders, although those who volunteered reported more health-promoting

behaviors than those who did not volunteer. The finding that the elders with more education engaged in more health promoting behaviors has been reported elsewhere (Acton & Malathum,

2000).

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

BARRIERS TO HEALTH PROMOTION

183

Increasing health-promoting behaviors in elders may have many benefits. In a study of elders

(60 and older), Armer and Conn (2001) found that physical activity was significantly associated

with self-rated health. In a study of men who were 55 and older, Loeb (2004) reported that men

who practiced more health-promoting behaviors also reported better health. In addition, health

promotion has been linked to spirituality with elders reporting more spirituality also engaging in

more health promoting behaviors (Armer & Conn, 2001; Callaghan, 2006).

The findings of our study suggest that interventions to reduce attentional demands may allow community dwelling elders to increase their health promoting behaviors and potentially improve their health. Many nursing interventions to reduce attentional demands in the physical-environmental, informational, behavioral, and affective domains have been proposed

(Jansen, 2006). Although the effects of aging may increase attentional demands, this research

suggests that the greatest increase in attentional demands occurred in the 75- to 84-year-old

group. The subjects who were 85 and older did not see a significant increase in attentional demands. That the 85-year-old and older subjects are still living in the community may suggest

that they are reasonably healthy and least affected by attentional demands related to aging. Elders who have many attentional demands may no longer be able to live in the community at this

age. Thus, the 65- to 74-year-old age group might be a target group for interventions to reduce

elders attentional demands.

Many of the items that the elders in this study found most demanding (see Tables 3 & 4) were

physical or environmental demands (Jansen & Keller, 1999). The physical environment can be

modified proactively to support independence and safety by providing handholds for stability, visual cues for sequencing or better lighting for reading medication information. Lawton (1982), a

pioneer in the field of environmental gerontology, explored interactions between older adults and

the environment. He created the theoretical framework used to study how the physical environment could act as barriers or as a support to function, recognizing that needs change with age, illness, or injury. Over the years, his work has led to studies that support the effectiveness of environmental modifications as an important part of an intervention package that reduces nursing home

admissions, reduces falls and fear of falling that leads to inactivity, and supports continued independence (Beswicket et al., 2008; Gillespie, Gillespie, Robertson, Lamb, Cumming, & Rower,

2003). Even minor changes to the physical environment can increase ease of use and support

healthy behaviors in a variety of ways.

Medication adherence is an important health-promotion behavior employed by the elderly,

with approximately 74% of community-dwelling elders taking at least one prescription medication (Swanland, Scherk, Metcalf, & Jesek-Hale, 2008). The item managing medications required the least effort for the first two age groups according to the findings in this study. However, McDonald-Miszczak, Neupert, and Gutman (2008) reported that elderly subjects

overestimated their adherence with medication, with younger-old adults self-reports less accurate than those of the older-old adults. Cognitive status, executive function, and working memory have been correlated positively in studies addressing medication adherence in community-dwelling elderly (Insel, Morrow, Brewer, & Figueredo, 2006; McDonald-Miszczak et al.,

2008). In both studies, the elderly subjects were less accurate in managing medications when

distractions or busyness occurred between the time they remembered that a medication needed

to be taken and when they actually took the medication. Although the elderly adults in this

study did not perceive medication management as an attentional demand, their actual adherence

is unknown.

184

STARK, CHASE, DEYOUNG

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING

The findings of this study help to inform nursing care of community-dwelling elders in several

ways. First, nurses working with community-dwelling elders often address health promotion activities regardless of the current health status of the client. Knowing the domains of attentional demands can assist nurses and others involved in caring for community dwelling elders in identifying health maintenance and illness/injury prevention needs so as to teach adaptive skills for

normal aging and assist in primary prevention. Commitment to a new health behavior requires focused attention and continuous problem-solving. For example, senior centers reach a wide audience and provide health promotion education, screening, and interventions through a variety of

programs. By focusing on attentional demands that may deter health promoting behaviors, elders

may find health promoting behaviors to be achievable. In addition, teaching elders how to reduce

attentional demands may improve daily functioning in other areas (Jansen, 2006).

This research also informs care for secondary prevention, or early diagnosis and treatment of

illness, as elders who encounter high attentional demands may experience more barriers to health

promotion. For example, elderly persons with a new diagnosis of congestive heart failure must address a number of changes simultaneously to manage their illness. New medications need to be

learned and a strategy to take them accurately must be planned. Diet restrictions require altering

grocery shopping habits, as well as eating habits, with new recipes needing to be learned. Being

aware of, and interpreting the meaning of, physical changes requires attention as well.

In tertiary prevention, or recovery and rehabilitation, nurses can focus on interventions to reduce attentional demands for clients after an injury or illness so as to facilitate recovery and independence. Nurses may find that an assessment tool such as the ADS may help in identifying elderly clients at greater risk for problems in managing a complex chronic illness. Adaptations to

the environment, assistive technology, or new techniques may provide support for these necessary

and important changes. Other home care team members, such as occupational therapists, can assess, recommend, and train in the use of these techniques to support nursing goals. An example of

this would be when someone who is diabetic has a stroke with residual weakness on one side of the

body. New methods for monitoring blood sugar levels, for storing and opening medications or preparing healthy foods may be necessary to manage medical issues appropriately with this new

physical challenge in order to support health promotion.

Second, the findings of this study suggest that although the ADS has been used as a research

tool (Jansen & Keller, 1999), adapting it for clinical assessments may be beneficial. Health care

providers who are aware of high attentional demands can more easily identify supportive services

to help clients maintain independence and health-promotion behaviors. Routinely monitoring

attentional demands, such as during annual exams or screenings, changes in magnitude or domains of demands can indicate need for further evaluation and for interventions to reduce

attentional demands (Jansen, 2006). For example, home care and hospice staff can assess the

attentional demands of elderly caregivers that may interfere with learning about new medications,

physical or occupational therapy exercises, or symptom management. Supportive interventions

can be introduced to increase the likelihood of success. Primary health care providers could use an

assessment of attentional demands during annual physicals to monitor the clients ability to manage attentional demands. High scores in a particular domain or scores increasing over time may indicate that the client needs supportive services or transition to assisted living. Adaptation and testing of the ADS as a clinical assessment is needed.

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

BARRIERS TO HEALTH PROMOTION

185

In this study, the 75- to 84-year-old age group had the most significant increase in attentional

demands. They also reported the strongest relationship between ADS and health promotion, suggesting that this group encounters more barriers that interfere with their ability to continue activities that promote health. The findings of this study suggest that community health nurses or other

care providers should consider targetingyounger elders with interventions to reduce attentional

demands so that they might have tools and strategies in place before the demands become overwhelming. Reducing barriers such as attentional demands may empower elders to engage in

health promotion that will better support them living in and contributing to the community.

There are some limitations of the study that must be considered. First, the sample was very homogeneous and highly educated. This suggests that they have resources not available to many elders. Second, this was a survey and has all the limitations of survey research; who actually completed the survey is not known. Third, the health status and diseases of the individuals in this

sample is unknown. Their attentional demands and health promotion may be related to their current health status, rather than attentional demands. Last, that attentional demands serve as barriers

was an application of the HPM; the research design does not allow for attribution of causation.

In summary, elders experience some changes during aging that affect attention. The results of

this study suggest that these attentional demands can affect their health promotion. Nurses and

other health care providers who care for community-dwelling elders can help the elders, their families, and the communities in which they live to take measures to reduce demands (Jansen, 2006).

In doing so, nurses have an opportunity to impact elders ability to engage in health promoting

activities.

REFERENCES

Acton, G. J., & Malathum, P. (2000). Basic need status and health-promoting self-care behavior in adults. Western Journal

of Nursing Research, 22, 796811.

Armer, J. M., & Conn, V. S. (2001). Exploration of spirituality and health among diverse rural elderly individuals. Journal

of Gerontological Nursing,27(6), 2937.

Beswick, A. D., Rees, K., Dieppe, P., Ayis, S., Gooberman-Hill, R., Horwood, J., & Ebrahim, S. (2008). Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independentliving in elderly people: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet, 371, 725735.

Callaghan, D. M. (2006). The influence of growth on spiritual self-care agency in an older adult population. Journal of Gerontological Nursing,32(9), 4351.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003). Public health and aging: Trends in aging - United States and worldwide. Retrieved May 12, 2010 fromhttp://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5206a2.htm.

Gillespie, L. D., Gillespie, W. J., Robertson, M. C., Lamb, S. E., Cumming R. G.,& Rower, B. H., (2003). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1,CD000340. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000340.

Insel, K., Morrow, D., Brewer, B., & Figueredo, A (2006). Executive function, working memory, and medication adherence among older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 61B, 102107.

Jansen, D. A. (2006). Attentional demands and daily functioning among community dwelling elders. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 23, 113.

Jansen, D. A., & Keller, M. L. (1999). An instrument to measure the attentional demands of community-dwelling elders.

Journal of Nursing Measurement, 7, 197214.

Jansen, D. A., & Keller, M. L. (2003). Cognitive function in community-swelling elderly women: Attentional demands

and capacity to direct attention. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 29 (7), 3443.

Kail, R. V., & Cavanaugh, K. C. (2010). Human development: A life-span view(5thed.). Florence, KY:Thomson/Wadsworth.

Lawton, M. P. (1982). Competence, environmental press and the adaptation of older people. In M. P. Lawton, P. G.

Windley, & T. O. Byerts (Eds.), Aging and the environment: Theoretical approaches (pp. 3359). New York: Springer.

Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 19:55 20 September 2012

186

STARK, CHASE, DEYOUNG

Leenerts, M. H., Teel, C. S., & Pendleton, M. K. (2002). Building a model of self-care for health promotion in aging. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 34, 355361.

Loeb, S. J. (2004). Older mens health: Motivation, self-ratings, and behaviors. Nursing Research, 53, 198206.

McDonald-Miszczak, L., Neupert, S. D., & Gutman, G. (2009). Does cognitive ability explain inaccuracy in older adults

self-reported medication adherence? Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28, 560581.

Ojha, H. A., Kem, R. W., Lin, C., & Winstein, C. J. (2009). Age affects the attentional demands of stair ambulation: Evidence from a dual-task approach. Physical Therapy, 89, 10801088.

Pender, N., Murdaugh, C., & Parsons, M. A., (2001). Health promotion in nursing practice (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River,

NJ: Pearson Education.

Pender, N., Murdaugh, C., & Parsons, M. A., (2005). Health promotion in nursing practice (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River,

NJ: Pearson Education.

Shumway-Cook, A., & Woollacott, M. (2000). Attentional demands and postural control: The effect of sensory context.

Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 55A, M10M16

Swanland, S. L., Scherck, K. A., Metcalfe, S. A., & Jesek-Hale, S. R. (2008). Keys to successful self-management of medications. Nursing Science Quarterly, 21, 238246.

Stark, M. A.,& Cimprich, B. (2003). Promoting attentional health: Importance to womens lives. Health Care for Women

International, 24, 93102.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Developing healthy people 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2010 from

http://www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020/Objectives/TopicArea.aspx?id=37&TopicArea=Older%20Adults.

Walker, S. N., & Hill-Polerecky, D. M. (1996). Psychometric evaluation of the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II. Unpublished manuscript, University of Nebraska Medical Center. Retrieved December 17, 2009 from http://app1.unmc.edu/

nursing/conweb/view_content.cfm?lev1=hplpii&lev2=(none)&lev3=(none)&pubstat=(none)&web=pub

Walker, S., Sechrist, K., & Pender, N. (1987). The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile: Development and psychometric

characteristics. Nursing Research, 36, 7681.

Young, H. M., & Capezuti, E. (2010). Celebrate age. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42, 111112.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Action Research PreseantationDokument29 SeitenAction Research PreseantationKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tiket Seminar FixedDokument2 SeitenTiket Seminar FixedKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Output - ArtikelDokument13 SeitenOutput - ArtikelKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Journey Across An Unwelcoming Field A Qualitative Study Exploring The Factors Influencing Nursing Students Clinical EducationDokument6 SeitenA Journey Across An Unwelcoming Field A Qualitative Study Exploring The Factors Influencing Nursing Students Clinical EducationKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educating Nursing Students About Health Literacy - From The Classroom To The Patient BedsideDokument11 SeitenEducating Nursing Students About Health Literacy - From The Classroom To The Patient BedsideKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Cultural and Linguistic Barriers To Health LiteracyDokument11 SeitenUnderstanding Cultural and Linguistic Barriers To Health LiteracyKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessing Health Literacy: Diagnostic TipsDokument2 SeitenAssessing Health Literacy: Diagnostic TipsKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Systematic Review of The Literature On Health Literacy in Nursing EducationDokument5 SeitenA Systematic Review of The Literature On Health Literacy in Nursing EducationKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.1. Core Competencies Diagram - 1Dokument1 Seite1.1. Core Competencies Diagram - 1Kusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Perspective of Healthcare Providers and Patients On Health Literacy - A Systematic Review of The Quantitative and Qualitative StudiesDokument11 SeitenThe Perspective of Healthcare Providers and Patients On Health Literacy - A Systematic Review of The Quantitative and Qualitative StudiesKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Giving and Receiving Feedback Participant GuideDokument72 SeitenGiving and Receiving Feedback Participant GuideKusrini Kadar Syamsalam0% (1)

- Surat DekanDokument1 SeiteSurat DekanKusrini Kadar SyamsalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Es 335 emDokument6 SeitenEs 335 emFirdosh Khan100% (2)

- 1 PBDokument17 Seiten1 PBaantiti12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Seven Elements For Capacity Development For Disaster Risk ReductionDokument4 SeitenSeven Elements For Capacity Development For Disaster Risk ReductionPer BeckerNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Teochew Chinese of ThailandDokument7 SeitenThe Teochew Chinese of ThailandbijsshrjournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- CBC1501-TL-101 2015 3 BDokument64 SeitenCBC1501-TL-101 2015 3 BJanke Van Niekerk50% (2)

- A Short Survey On The Usage of Choquet Integral and Its Associated Fuzzy Measure in Multiple Attribute AnalysisDokument8 SeitenA Short Survey On The Usage of Choquet Integral and Its Associated Fuzzy Measure in Multiple Attribute AnalysisfarisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student Leave Management System Ijariie6549Dokument8 SeitenStudent Leave Management System Ijariie6549SteffenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Think Global and British Council The Global Skills GapDokument12 SeitenThink Global and British Council The Global Skills GapSherry LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIK - msl.00166 ReportDokument3 SeitenCIK - msl.00166 ReportChristopher Edward Martin FlanaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of E-Bills Payment On Customer Satisfaction in Uganda: Stanbic Bank Uganda Limited As The Case StudyDokument8 SeitenImpact of E-Bills Payment On Customer Satisfaction in Uganda: Stanbic Bank Uganda Limited As The Case Study21-38010Noch keine Bewertungen

- OrganizingDokument46 SeitenOrganizingViswajeet BiswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Model Question Paper AnsDokument19 SeitenModel Question Paper Ansnavadeep saiNoch keine Bewertungen

- University of Auckland PHD Thesis GuidelinesDokument6 SeitenUniversity of Auckland PHD Thesis Guidelinesygadgcgld100% (1)

- Pantaloons Employee Satisfaction Towards CompensationDokument61 SeitenPantaloons Employee Satisfaction Towards CompensationkaurArshpreet57% (7)

- CHIFAMBA MELBAH R213866M .Test InclassDokument3 SeitenCHIFAMBA MELBAH R213866M .Test InclasswilsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhaka Ashulia Pre Feasibility ReportDokument332 SeitenDhaka Ashulia Pre Feasibility ReportAdeev El AzizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zamoras Group Research About GAS StudentsDokument17 SeitenZamoras Group Research About GAS StudentsLenard ZamoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ModelingDokument18 SeitenModelingLibya TripoliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oklahoma State University Findings On MorgellonsDokument4 SeitenOklahoma State University Findings On MorgellonsSpace_Hulker100% (5)

- ArchanaDokument6 SeitenArchanaArchana DeviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constructing ProbabilityDokument25 SeitenConstructing ProbabilityBianca BucsitNoch keine Bewertungen

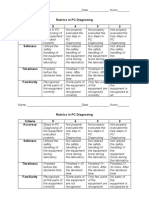

- Rubrics in PC Diagnosing Criteria 5 4 3 2 Accuracy: Name - Date - ScoreDokument2 SeitenRubrics in PC Diagnosing Criteria 5 4 3 2 Accuracy: Name - Date - Scorejhun ecleoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ey The Indian Organic Market Report Online Version 21 March 2018Dokument52 SeitenEy The Indian Organic Market Report Online Version 21 March 2018Kamalaganesh Thirumeni100% (2)

- Critique Paper BSUDokument4 SeitenCritique Paper BSUAndrei Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To List Masters Thesis On ResumeDokument4 SeitenHow To List Masters Thesis On Resumebk4h4gbd100% (2)

- DR Dilip Pawar - Clinical Research in IndiaDokument37 SeitenDR Dilip Pawar - Clinical Research in IndiaRahul NairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cost and Benefit Analysis of Solar Panels at HomeDokument8 SeitenCost and Benefit Analysis of Solar Panels at HomePoonam KilaniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Predicting Advertising Success Beyond Traditional Measures: New Insights From Neurophysiological Methods and Market Response ModelingDokument19 SeitenPredicting Advertising Success Beyond Traditional Measures: New Insights From Neurophysiological Methods and Market Response ModelingRccg DestinySanctuaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurial Intentions and Corporate EntrepreneurshipDokument22 SeitenEntrepreneurial Intentions and Corporate Entrepreneurshipprojects_masterzNoch keine Bewertungen