Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Jewish Dialect and New York Dialect

Hochgeladen von

Tuvshinzaya GantulgaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Jewish Dialect and New York Dialect

Hochgeladen von

Tuvshinzaya GantulgaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

American Dialect Society

Jewish Dialect and New York Dialect

Author(s): C. K. Thomas

Source: American Speech, Vol. 7, No. 5 (Jun., 1932), pp. 321-326

Published by: Duke University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/452953

Accessed: 20-02-2016 03:43 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Duke University Press and American Dialect Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Speech.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 160.39.5.105 on Sat, 20 Feb 2016 03:43:04 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOLUME VII

NUMBER 5

domerican

Speech

JUNE - 1932

JEWISH DIALECT AND NEW YORK DIALECT

C. K. THOMAS

Cornell University

URINGthe past four years I have worked with some hundreds of

university students in an attempt to improve the quality of

their speech. A fair proportion of these students have been

Jews from New York City and its suburbs. Their social and scholastic

levels are about the same as those of other New Yorkers, but their

speech is distinctly inferior, and this inferiority raised the question

whether there might be a clearly defined dialect which was characteristic of New York Jews. The students with whom I have worked do

not, of course, constitute a true cross-section of either New York or

Jewish speech; such a cross-section would have to be obtained in New

York itself. Those who can afford to travel 250 miles for their education represent, on the average, a higher social and economic level than

those who stay at home and who are able, in many cases, to earn a

larger part of their expenses than is possible in a small town. Because

of this higher level, and because few of the New York Jews at Cornell

speak any language but English, their dialect is by no means as extreme

as that of the peripatetic Mr. Klein so carefully studied by Miss

Benardete,1 or even as extreme as that of the general run of Jewish

undergraduates in the New York City colleges. Many of them, however, have complicated their speech problem with tricks acquired in the

elocution schools that are at present so popular among the higher

class Jewish families of New York. Traditional Jewish and traditional

New York pronunciations alike are in some cases conspicuously absent.

Moreover, most of the students with whom I am familiar are to some

extent conscious of their speech, for the greater number of them are sent

1 Dolores Benardete, "Immigrant Speech-Austrian-Jewish Style,"

SPEECH,

AMERICAN

October, 1929.

321

This content downloaded from 160.39.5.105 on Sat, 20 Feb 2016 03:43:04 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

American Speech

322

to me from courses in public speaking and dramatics. All of these

factors complicate the problem of analysis, and make the results less

conclusive.

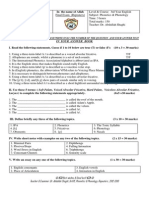

For purposes of comparison I divided my students into three groups:

(1) Jews from New York City and its suburbs, (2) Gentiles from the

same area, (3) Jews who had lived all their lives at a distance from New

York City. After discarding all doubtful cases, namely, those of

uncertain racial origin, those who had lived both in New York City and

elsewhere, and those who lived in the typically Jewish summer resorts

of the Catskills, I was left with the records of 112 students, of whom 75

were New York Jews, 19 were New York Gentiles, and 18 were Jews

from other parts of the country. Thus approximately 67 percent of

the total was in group 1, 17 percent in group 2, and 16 percent in group

3. A normal distribution of dialectal peculiarities, or errors, would

therefore result in the same percentages, but when the errors had been

classified it was found that, out of a total of 673, the New York Jews

had made 522, the New York Gentiles 71, and the Jews from other

parts of the country 80. In other words, group 1 made 78 percent of

the errors, group 2 made 10 percent, and group 3 made 12 percent.

Thus, in comparison with an average distribution, the speech of group 1

was distinctly inferior to that of the other two groups, as the following

summary shows:

Group

1

A Number of cases in each group.........

B Percentage of cases...................

C Number of errors in each group........

D Percentage of errors..................

E Percentage above or below average dis.......

tribution2.............

75

67

522

78

+16

19

17

71

10

18

16

80

12

-38

Total

112

100

673

100

-26

In considering the distribution of particular errors among the three

groups, one must refer to line D in the above table as a basis for comparison. If the percentages for the particular error do not vary greatly

from those of line D it is obvious that they give no information regard2 These figures represent the variation from 100 of the quotients obtained by

dividing the figures in line D by the correspondingfigures in line B; in all calculaions the percentages were carried to two extra decimals.

This content downloaded from 160.39.5.105 on Sat, 20 Feb 2016 03:43:04 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Jewish Dialect

323

ing the source of the error; but if the percentage for group 1, consisting

of New York Jews, is higher than 78, that of group 2, consisting of New

York Gentiles, higher than 10, and that of group 3, consisting of Jews

from other localities, lower than 12, the distribution creates a strong

presumption that the error in question is local rather than racial, for

only the groups which include New Yorkers show a higher percentage

than the average distribution. Similarly, if the percentages for another

error are above the average for groups 1 and 3, and below for group 2,

the distribution creates a strong presumption that this is a racial,

rather than a local, error, for only the groups which include Jews show

higher percentages than the average. In many cases, of course, there

are neither sufficiently large numbers of instances of the error nor

sufficiently great variations from the average to warrant any definite

conclusion; in other cases, which are listed below, definite conclusions

are inescapable.

The most frequent error among these students was the dentalizing

of the alveolar consonants [t, d, n, 1, s, z];"the error consists in making

the characteristic consonantal obstruction between the tongue and teeth

instead of between the tongue and gum ridge. The acoustic effect of

this misplacement is least noticeable for [n, 1]; for [s, z] it suggests a

slight lisp; [t, d] sound overexplosive and slightly higher in pitch. It is

most noticeable when several alveolar consonants appear in the same

word, as in dental and slant. The distribution of this error clearly

indicates that it is Jewish in origin: group 1 is 10 percent above, and

group 3 is 5 percent below, the average distribution of line D; but group

2, the Gentile group, is 66 percent below the average. In short, the

Gentile group is remarkably free from this error, including only 8

instances out of a total of 224. The most frequently dentalized of

these consonants is [1], and here the distribution is even more clearly

Jewish: 10 percent above the average for group 1, 5 percent above for

group 3, and 80 percent below for group 2. The cause of this error,

whether a survival from Yiddish, German, or Slavic linguistic habit or

otherwise, is not within the scope of this paper.

Closely associated with dentalization is the overaspiration of [t]

after [n] or [1], particularly at the beginning of an unstressed syllable

or at the end of a word, as in winter, wilted, went, and wilt. Here the

percentages are inconclusive, but it seems likely that this error is also

Jewish.

Letters in square brackets are phonetic characters, which refer to sounds;

those in quotation marks refer to spellings.

This content downloaded from 160.39.5.105 on Sat, 20 Feb 2016 03:43:04 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

324

American Speech

Difficulty with [s] seems to be characteristic of Jewish speech. This

is in part owing to the habit of dentalizing, but in addition there are

other errors: exaggerated hissing, substitution of voiceless [1]and "th"

[6] as in thin, and occasionally "sh" [f] as in she. There are 35 instances

of these variations, of which only 3 are Gentile. Group 3, consisting of

Jews who do not live in New York City, has the greatest difficulty with

this sound, being 68 percent above the average distribution.

Another clearly Jewish error is the substitution of [rig]for [i], so as,

for instance, to make singer a rhyme for finger. There are 35 instances

of this error in the three groups, and only one of them is Gentile.

Furthermore, according to these figures, the Jews from New York do

not make this error quite as persistently as do those from other localities. The substitution of [ijk] for [rJ],so as, for instance, to make sing

and sink identical in sound, appears only 8 times. Though this is the

traditional form of the error, perhaps because it can be represented

more easily in the conventional alphabet, I do not believe it to be

nearly as common as [rig]. Once in a great while the glottic stop is

added instead of either [k] or [g].

Loss of the distinction between the voiced [w] and the voiceless

"wh" [Ml,so as, for instance, to make witch and which identical, is

quite common in both New York groups, but less common among the

Jews from other localities. The distribution is 4 percent above the

average from group 1, 60 percent above for group 2, and 29 percent

below for group 3. In other words, the Jews from outside of New

York have least trouble with the voiceless [M],and this bears out the

traditional notion that, although this error is by no means confined

to New York, it is there most conspicuous and prevalent.

Similarly, the addition of an [r] to such words as idea and law,

especially when the following word begins with a vowel, is, at least for

these three groups, a New York characteristic, for none of group 3

added the [r], and group 2, the Gentile group, added it more consistently

than group 1. The error is not, of course, limited to New York City,

but is also encountered in New England.

Errors in vowels and diphthongs are, with some doubtful exceptions, New Yorkese rather than Jewish. The vowel [o(v)] is distorted

into an exaggerated diphthong which can best be indicated as [ev] or

[ev], as in the pronunciation [nevt] for note [no(v)t]. This is similar to

the extreme pronunciation of Oxford, though it is drawled to a greater

length in New York. Group 1 is 2 percent above the average for this

error, group 2 is 31 percent above, but group 3 is 42 percent below.

This content downloaded from 160.39.5.105 on Sat, 20 Feb 2016 03:43:04 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Jewish Dialect

325

It should be noted that the Gentile group has the most trouble with

this sound.

Another characteristic error is the substitution of the compromise

[a] for the flat [m] in such words as land, man, and bad. This differs

from the New England use of [a] and the Southern British use of [a] in

such words as path, dance, and laugh, and is more like certain Scotch

and Irish dialects. A possible explanation may lie in the concerted

efforts now being made in New York to teach the "broad a" [a] of

"world standard" English. One who acquires this "broad a," or

even the compromise [a], some years after learning to speak English is

likely to use it in the wrong words, and at the same time to get the

impression that the "flat a" [oe]is a disreputable sound, to be avoided

whenever possible. At any rate, group 3 is least susceptible to the

error, and group 1, which has had the greatest amount of elocutionary

training, the most susceptible.

Substitution of [yev]for [av] in such words as now, out, and power

appears not to be a Jewish error. Group 1 is 3 percent below average,

group 3 is 5 percent below, and group 2, the Gentile group, is 29 percent

above. This error is characteristic of the South and of rural New

England as well as of New York, and its significance in this study is

doubtful.

The change of the diphthong in my, fine, and light from [ai] to [aI], or

to an even more retracted form, appears to be a New York characteristic, though more data will be required for certainty. In its most

characteristic form the distortion resembles the German variety of the

diphthong more closely than anything else. Group 1 is 12 percent

above the average; group 2 is 10 percent below; group 3, however,

includes only one instance of the error.

Statistical figures on vocal quality are much less reliable, as the

qualities themselves are so variable. In general, however, indistinctness resulting from inactivity of the lips appears to be a New York

characteristic, drawl is more common among the Jews, and "throatiness" exclusively Jewish. Nasality is common, and not limited to

either group.

So far, then, as can be learned from the data of this study, the New

York Jew dentalizes the alveolar consonants, overaspirates [t], has

and has a drawling, throaty vocal

various difficulties with [s] and

[ra],

quality because he is Jewish; on the other hand, he uses the voiced

[w] for the voiceless [&], substitutes [ev] for [o(v)], [a] for [em],[mev]for

[av], and [ai] for [ai] adds, the intrusive [r], and uses his lips insufficiently

This content downloaded from 160.39.5.105 on Sat, 20 Feb 2016 03:43:04 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

326

American Speech

because he is a New Yorker. Obviously these conclusions are tentative, and much more data will be required before any conclusions

approaching finality can be reached; but it seems evident, nevertheless,

that a good bit of what passes popularly for Jewish dialect is really New

York dialect, and that details which pass unnoticed in Gentile speech

are more apt to be noticed in Jewish speech because of the lower

quality resulting from the mixture of errors from local and racial

sources.

This content downloaded from 160.39.5.105 on Sat, 20 Feb 2016 03:43:04 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Study Guide for Heinrich Boll's "Christmas Not Just Once a Year"Von EverandA Study Guide for Heinrich Boll's "Christmas Not Just Once a Year"Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ways of the World: Theater and Cosmopolitanism in the Restoration and BeyondVon EverandWays of the World: Theater and Cosmopolitanism in the Restoration and BeyondNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Informed and Reflective Approach to Language Teaching and Material DesignVon EverandAn Informed and Reflective Approach to Language Teaching and Material DesignNoch keine Bewertungen

- LICENCE LLCE 3 Specialité Anglais 2016-17Dokument30 SeitenLICENCE LLCE 3 Specialité Anglais 2016-17Sangyeon ParkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coupland (10) Welsh Linguistic Landscapes From Above and Below Final With FigsDokument37 SeitenCoupland (10) Welsh Linguistic Landscapes From Above and Below Final With FigsEDKitisNoch keine Bewertungen

- First You Write A Sentence The Elements of ReadingDokument4 SeitenFirst You Write A Sentence The Elements of ReadingPraneta IshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idioms in OthelloDokument27 SeitenIdioms in OthelloHelena LopesNoch keine Bewertungen

- LOST IN THE JUNGLE READING 2nd & 3rd ConditionalsDokument5 SeitenLOST IN THE JUNGLE READING 2nd & 3rd ConditionalsBahaus ConstrucNoch keine Bewertungen

- PrepostionDokument5 SeitenPrepostionSilvio DominguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- LICENCE LLCER 1 Spécialité AnglaisDokument11 SeitenLICENCE LLCER 1 Spécialité AnglaisSangyeon Park0% (1)

- Reporting Verbs - Docx 0Dokument2 SeitenReporting Verbs - Docx 0Irati C-iNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tabloidization Conquers Quality PressDokument11 SeitenTabloidization Conquers Quality PressretrosoulNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of EnglishDokument4 SeitenHistory of EnglishEd RushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broadsheets vs. Tabloids: Neutrality vs. SensationalismDokument22 SeitenBroadsheets vs. Tabloids: Neutrality vs. Sensationalismduneden_1985100% (5)

- Additional Grammar TestDokument4 SeitenAdditional Grammar TestJulius Halls Hall0% (1)

- Word Form: Parts of SpeechDokument33 SeitenWord Form: Parts of SpeechPouyan Mobasher AminiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender and The Practice of TranslationDokument5 SeitenGender and The Practice of TranslationBelén TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anglicisms in EuropeDokument30 SeitenAnglicisms in EuropeValerie MaduroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language Varieties and Standard LanguageDokument9 SeitenLanguage Varieties and Standard LanguageEduardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Culture in Language Learning: Background, Issues and ImplicationsDokument10 SeitenCulture in Language Learning: Background, Issues and ImplicationsIJ-ELTSNoch keine Bewertungen

- 73690Dokument7 Seiten73690Lika ShubitidzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposal For A Hieronymic OathDokument17 SeitenProposal For A Hieronymic OathAna Levi100% (1)

- Phonetics and PhonologyDokument11 SeitenPhonetics and PhonologyMushmallow BlueNoch keine Bewertungen

- ELP Language Biography Checklists For Young Learners enDokument8 SeitenELP Language Biography Checklists For Young Learners enhigginscribdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kaplan 1966 Language LearningDokument20 SeitenKaplan 1966 Language Learningnhh209Noch keine Bewertungen

- Corpus Design and Types of CorporaDokument68 SeitenCorpus Design and Types of CorporaDr. Farah KashifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lectures - Translation TheoryDokument31 SeitenLectures - Translation TheoryNataliia DerzhyloNoch keine Bewertungen

- J. Writing Guide 7 Ways To Paraphrase3Dokument9 SeitenJ. Writing Guide 7 Ways To Paraphrase3longpro2000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Text Typology PDFDokument7 SeitenText Typology PDFPatricia Andreea Loga100% (1)

- My Son of The Fanatic by Hanif KureishiDokument4 SeitenMy Son of The Fanatic by Hanif KureishisaifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kukharenko A Book of Practice in Stylistics-108Dokument80 SeitenKukharenko A Book of Practice in Stylistics-108soultaking100% (17)

- A Sociolinguistic Study of Shifting FormalitiesDokument17 SeitenA Sociolinguistic Study of Shifting FormalitiesCristian foreroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cohesive Features in Argumentative Writing Produced by Chinese UndergraduatesDokument14 SeitenCohesive Features in Argumentative Writing Produced by Chinese UndergraduateserikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writings of H.E. PalmerDokument228 SeitenWritings of H.E. PalmerKhalifa83Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive Linguistics and TranslationDokument3 SeitenCognitive Linguistics and TranslationCristina Toma100% (1)

- НіколяDokument22 SeitenНіколяАнтоніна ПригараNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accents of English Handout 1Dokument4 SeitenAccents of English Handout 1kosta2904Noch keine Bewertungen

- Translators Endless ToilDokument6 SeitenTranslators Endless ToilMafe NomásNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bai Tap Cuoi ModuleDokument13 SeitenBai Tap Cuoi ModulehadiemdiemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reiner Keller - Doing Discourse Research - An Introduction For Social Scientists-SAGE Publications LTD (2012)Dokument169 SeitenReiner Keller - Doing Discourse Research - An Introduction For Social Scientists-SAGE Publications LTD (2012)Lu CamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Irony in The Semantics-Pragmatics InterfaceDokument13 SeitenIrony in The Semantics-Pragmatics InterfaceAhmed S. MubarakNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Prior Knowledge in L3 LearningDokument25 SeitenThe Role of Prior Knowledge in L3 LearningKarolina MieszkowskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Matsuda - Process and Post-Process PDFDokument19 SeitenMatsuda - Process and Post-Process PDFLuisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Changing Places Lodge Literatura InglesaDokument44 SeitenChanging Places Lodge Literatura Inglesalolaconalas100% (3)

- Second Language Acquisition of Definiteness - a Feature Based Contrastive Approach to Second Language Learnability - 副本Dokument313 SeitenSecond Language Acquisition of Definiteness - a Feature Based Contrastive Approach to Second Language Learnability - 副本Yufan HuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thornbury On NoticingDokument10 SeitenThornbury On Noticingdhtl20030% (1)

- Market Leader Intermediate Lesson Plan Unit 1 Activity Mode of Work Time (Min)Dokument2 SeitenMarket Leader Intermediate Lesson Plan Unit 1 Activity Mode of Work Time (Min)Y HNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tarnovskaya M L Proficiency in EnglishDokument240 SeitenTarnovskaya M L Proficiency in EnglishAnnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Littleetal 2003 PDFDokument261 SeitenLittleetal 2003 PDFPaulina-Noch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of Translation 1 SyllabusDokument3 SeitenTheory of Translation 1 SyllabusRamil Gofredo0% (1)

- The Conservation of Races The American Negro Academy. Occasional Papers No. 2Von EverandThe Conservation of Races The American Negro Academy. Occasional Papers No. 2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Population and Society An Introduction To Demography 2Nd Edition Poston Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDokument27 SeitenPopulation and Society An Introduction To Demography 2Nd Edition Poston Test Bank Full Chapter PDFreality.brutmhk10100% (8)

- The Conservation of RacesVon EverandThe Conservation of RacesNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Many Languages Do We Need?: The Economics of Linguistic DiversityVon EverandHow Many Languages Do We Need?: The Economics of Linguistic DiversityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biological and Cultural Consequences of Miscegenation and Family MarriageDokument8 SeitenBiological and Cultural Consequences of Miscegenation and Family MarriagesirorrinNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Languages, and Why We Should Study ThemVon EverandAmerican Languages, and Why We Should Study ThemNoch keine Bewertungen

- How You Say It: Why We Judge Others by the Way They Talk—and the Costs of This Hidden BiasVon EverandHow You Say It: Why We Judge Others by the Way They Talk—and the Costs of This Hidden BiasBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Language and Globalization: The History of Us AllVon EverandLanguage and Globalization: The History of Us AllNoch keine Bewertungen

- Darden - How To Study and Discuss CasesDokument3 SeitenDarden - How To Study and Discuss CasesTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Wallace Stevens - by Marianne Moore - The New York Review of BooksDokument2 SeitenOn Wallace Stevens - by Marianne Moore - The New York Review of BooksTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cover Letter Samples - Wharton MBADokument0 SeitenCover Letter Samples - Wharton MBAJason Jee100% (4)

- Tim Ferriss - Transcripts of His ConversationsDokument680 SeitenTim Ferriss - Transcripts of His ConversationsTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SLE Syllabus Winter 92-93Dokument15 SeitenSLE Syllabus Winter 92-93Tuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SLE Syllabus Spring 10-11Dokument7 SeitenSLE Syllabus Spring 10-11Tuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- To George Shultz Re Gilead Board 11-09-1998 (II-141-1)Dokument1 SeiteTo George Shultz Re Gilead Board 11-09-1998 (II-141-1)Tuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Room Rate: Room Type: Single DoubleDokument1 SeiteRoom Rate: Room Type: Single DoubleTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Am A Digital Cat-EnglishDokument14 SeitenI Am A Digital Cat-EnglishHieu TruongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excel ShortcutsDokument17 SeitenExcel ShortcutsTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 87DeptStBulli PDFDokument101 Seiten87DeptStBulli PDFTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sec. Shultz Speech On MongoliaDokument1 SeiteSec. Shultz Speech On MongoliaTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gordon 1997 Everyday Life As An Intelligence Test Effects of Intelligence and Intelligence ContextDokument118 SeitenGordon 1997 Everyday Life As An Intelligence Test Effects of Intelligence and Intelligence ContextTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Room Rate: Room Type: Single DoubleDokument1 SeiteRoom Rate: Room Type: Single DoubleTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FulltextDokument8 SeitenFulltextTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mazower - International CivilizationDokument14 SeitenMazower - International CivilizationTuvshinzaya GantulgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eric Kandel - in Search of MemoryDokument242 SeitenEric Kandel - in Search of MemoryTuvshinzaya Gantulga100% (10)

- Clyde Peters Say It Right in Chinese 2009 PDFDokument35 SeitenClyde Peters Say It Right in Chinese 2009 PDFMichelle SuenNoch keine Bewertungen

- TFF Theory FileDokument92 SeitenTFF Theory FileNathanGladneyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oath of Allegiance or DoptDokument4 SeitenOath of Allegiance or DoptRajarshiDharNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is A PBX Phone SystemDokument1 SeiteWhat Is A PBX Phone SystemPappu KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Newsite KPI Check. - Ver2Dokument4.183 SeitenNewsite KPI Check. - Ver2nasircugaxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jaskula Ed. LSCL7.PrepublicationDokument137 SeitenJaskula Ed. LSCL7.Prepublicationflibjib8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Com - PSTNDokument15 SeitenCom - PSTNJoseph ManalangNoch keine Bewertungen

- s1008 ActivitiesDokument4 Seitens1008 ActivitiesMilton MotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On ProsodyDokument27 SeitenNotes On ProsodyTwana1Noch keine Bewertungen

- IPA Pronunciation GuideDokument20 SeitenIPA Pronunciation GuideF_Community100% (1)

- Lesson 6Dokument7 SeitenLesson 6kshitijsaxenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phonetic Classes:: - Monophthongs. - Diphthongs (And Triphthongs) A Difference in How Many Vowels Are Found Within OneDokument3 SeitenPhonetic Classes:: - Monophthongs. - Diphthongs (And Triphthongs) A Difference in How Many Vowels Are Found Within OnePaul Elek Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 Peresectives On Phonological Theory and DevelopmentDokument265 Seiten2014 Peresectives On Phonological Theory and DevelopmentTayse MarquesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Area CodesDokument13 SeitenArea CodesjpschubbsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avaya - SIP Trunking in The EnterpriseDokument13 SeitenAvaya - SIP Trunking in The EnterpriseRafael PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- SBOA FormatDokument358 SeitenSBOA FormatSara DazzNoch keine Bewertungen

- 004 Vowel Power FAQDokument2 Seiten004 Vowel Power FAQNovita_100Noch keine Bewertungen

- Quantity-Sensitivity in Modern OTDokument5 SeitenQuantity-Sensitivity in Modern OTEric BakovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Albanian Armenian CelticDokument25 SeitenAlbanian Armenian CelticdavayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phonetics and Phonology Question PaperDokument1 SeitePhonetics and Phonology Question PaperDr. Abdullah Shaghi83% (6)

- Answer The Following Questions in A Concise Way and Using You Own WordsDokument2 SeitenAnswer The Following Questions in A Concise Way and Using You Own WordsMarisolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative and Superlative AdjectivesDokument3 SeitenComparative and Superlative AdjectivesSamerAliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Classical Theory of Fields 4rth Ed Landau and LifshitzDokument415 SeitenThe Classical Theory of Fields 4rth Ed Landau and LifshitzCamila LettiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Varieties of English - Anul IDokument41 SeitenVarieties of English - Anul IRamona Camelia100% (1)

- Spanish-English ArticulationDokument9 SeitenSpanish-English ArticulationLina LandazábalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magic JackDokument2 SeitenMagic Jackspaqueen2002Noch keine Bewertungen

- Verizon Subpoena ManualDokument10 SeitenVerizon Subpoena Manualali_winstonNoch keine Bewertungen

- IPcts E Brochure VoipDokument2 SeitenIPcts E Brochure VoipOliver NeptunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tie Line H323Dokument42 SeitenTie Line H323WaldirNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Letter Q Is Always Written With U and We Say, "KW." The Letter U Is Not A Vowel Here. (Quiet)Dokument2 SeitenThe Letter Q Is Always Written With U and We Say, "KW." The Letter U Is Not A Vowel Here. (Quiet)amritjosanNoch keine Bewertungen