Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in A Domestic Short Hair Cat

Hochgeladen von

Leyana AbdullahOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in A Domestic Short Hair Cat

Hochgeladen von

Leyana AbdullahCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY IN A DOMESTIC SHORT HAIR CAT

M.A. Nurliyana

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor,

Malaysia

SUMMARY

A 3 years old domestic short hair, male cat was presented to University

Veterinary Hospital-University Putra Malaysia (UVHUPM) for the complaint of

respiratory distress. Radiographic findings on the first day revealed pulmonary

oedema. However, it was initially diagnosed as bronchopneumonia. Problems

resolved after furosemide therapy, however, on day-4, the thoracic radiograph

revealed moderate enlargement of the heart with VHS 8.8 and valentine heart

shape. Full diagnostic investigation of the heart was conducted through

echocardiography. A diagnosis of feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) was

made from the echocardiographic evaluations based on the standard criteria by

American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM). Other diagnostic

workouts inclusive the blood pressure level and thyroid function test was

conducted to rule out hyperthyroidism and hypertension as secondary cause of

HCM.

Keywords: Pulmonary Oedema, Bronchopneumonia, Feline, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, VHS,

Echocardiography

INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

(HCM) is one of the most commonly

encountered heart disease in cats.

This disease is characterized by an

abnormal thickening (hypertrophy) of

one or several areas of the walls of

the heart, usually of the left ventricle

(ACVIM, n.d.). HCM was defined as a

diastolic left ventricular (LV) septal or

free wall thickness 6 mm (J.R.

Payne et.al, 2014).

CASE REPORT

Twin, 3 years old domestic

short hair, male cat, weighing 3.4 kg

was referred to University Veterinary

Hospital-Universiti Putra Malaysia

(UVH-UPM)

for

complaint

of

respiratory distress with appetite

bowel and urination are negative.

Upon physical examinations, the

temperature and pulse were within

the normal ranger, however, there

are

*Corresponding author: Nurliyana Meor

Abdullah

(M.A.

Nurliyana)

Email:

160647@student.upm.edu.my

increase in respiratory rate. Twin was

dyspnoeic with abdominal breathing

and

harsh

lung

sound

upon

auscultation.

A result of the complete blood

count

and

serum

biochemistry

analysis results were normal and did

not contribute towards determining

the cause of dyspnoea in this cat.

Thoracic radiograph was taken

on the first day to evaluate the

conditions. On lateral view, there are

loss of cardiac silhouette and

presence of mixed pattern of the

lung density at perihilar region with

bronchial, interstitial and alveolar

pattern. An initial diagnosis of

bronchopneumonia was made based

on the radiographic findings. As the

cat was dyspnoeic, intranasal oxygen

prong was conducted as initial

treatment above all. Other initial

medications that aimed to reduced

bronchopneumonia are administered

inclusive nebulization (NaCl and

gentamycin), Marbofloxacin 2mg/kg

(intravenously,

once

daily),

Aminophylline

5mg/kg

(intravenously,

twice

daily),

Tramadol 3mg/kg (intravenously,

three times daily), Dexamethasone

1mg/kg (intravenously, once daily).

However, the condition of the cat still

worsen and on day 2, the case was

re-diagnosed as pulmonary oedema

and furosemide therapy was started

aimed to reduce to the accumulation

of fluid. Second radiograph was

repeated and the pulmonary oedema

has resolved. However, from the

radiograph, there are moderate

enlargement of the heart with

Vertebral Heart Size (VHS) of 8.8,

bulging of the left atrium and

valentine

heart

shape.

Further

diagnostic investigation on the heart

was

conducted

through

echocardiography

and

revealed

enlargement of the left ventricular or

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

There are also increase in the left

atrium to aorta ratio suggestive of

left atrial enlargement.

From the M-mode evaluation

of the left ventricle, the left

ventricular wall or interventricular

septal thickness at end-diastole are

more than 6mm which indicate HCM.

The diagnosis was made based on

the standard criteria set by ACVIM.

Thyroid function test and blood

pressure parameter was determined

and the result was unremarkable

thus rule out the possibility of

hyperthyroidism and hypertension as

secondary cause of HCM in this case.

Echocardiographic

examination strongly pointed to a

diagnosis of Feline Hypertrophic

Cardiomyopathy. ACE inhibitor or

benazepril hydrochloride 0.5 mg/kg

( tab, orally, twice daily) was

indicated for HCM in this cat.

DISCUSSION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

is the most common cardiac disease

in the cat. A recent study showed

that in a cardiology referral centre,

46% of cats with heart disease

showed no clinical signs of heart

failure, which highlights how difficult

it can be for veterinary nurses to

recognize a cat with severe heart

disease (P. Charlotte, 2013). Similar

to patient in this case, often the cat

when presented, they are already in

CHF state.

Secondary

hypertrophic

diseases of the heart may be caused

by hyperthyroidism or hypertension,

and lead to signs that mimic HCM,

but if addressed early may be

reversible by treating the underlying

condition.

Primary HCM is not

reversible, and has been shown to

have a genetic link, particularly in

Main

Coons.

Unfortunately,

genotyping is not yet available. It is

not yet possible to isolate the gene

that causes HCM in cats, but through

studying family trees, it has been

shown to be an autosomal dominant

gene in some Main Coons and likely

other breeds as well. (J. Andrea,

2007). In Maine Coon (MC) cats the

c.91G > C mutation in the gene

MYBPC3, coding for cardiac myosin

binding protein C (cMyBP-C), is

associated with feline hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy

(fHCM).

The

mutation causes a substitution of an

alanine for a proline at residue 31

(p.A31P) of cMyBP-C (M. Christiansen

et.al, 2011).

Cats with HCM have reduced

left ventricular compliance that is

probably caused by a combination of

chamber

stiffness,

myocardial

fibrosis, impaired relaxation (an

active, oxygen and energy-requiring

process), and myocardial ischemia;

which reduces oxygen delivery

(Stokhof, 1997).

Cat with HCM also have

increased

risk

to

develop

a

devastating

complication

called

arterial thromboembolism (ATE). ATE

has been found in 12% to 28% of

cats

with

hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy (HCM) and 27% of

cats

with

unclassified

cardiomyopathy. In approximately

70% of cases, the embolization is to

the distal aorta (Smith et al., 2003).

Affected cat will experience acute,

painful condition causing cold and

paresis of the back legs.

Patient in this case was

presented

with

dyspnoea

and

abdominal breathing, thus, oxygen

therapy was indicated as a first line

treatment. This was supported by P.

Charlotte (2013) which stated that if

a cat presents to the veterinary

practice in respiratory distress, first

line treatment should include oxygen

therapy,

diuresis

and

minimal

handling.

Electrocardiography,

clinical

laboratory and ancillary studies do

not sufficiently distinguish HCM from

other forms of cardiomyopathy. Thus,

a careful clinical work up, including

high quality cardiac ultrasonography,

is required for definitive diagnosis.

Confirmation of LV hypertrophy,

including

papillary

muscle

thickening, is necessary for diagnosis

(V.L. Fuentes et.al, 2010)

For cats with HCM that are

already in congestive heart failure,

more

aggressive

therapy

is

necessary. Once the cat is stabilized,

other medications may be required.

Cats that are in heart failure and

have fluid accumulation in their

lungs often benefit from having

diuretics administered. (J. Ross,

2006). In this case, Furosemide is

indicated to treat the pulmonary

oedema.

For the treatment of HCM

itself, the choice is either ACE

inhibitor, Beta-blocker, or Calcium

channel blocker. However, none of

this treatment are

proven to

successfully treated HCM, but, it has

been documented to improve and

prolonged the quality of life of

affected cats.

To reduce the chance of a

thrombus forming within the heart,

many cats are given medications

that reduce the bloods ability to clot,

such as Aspirin or Clopidogrel.

CONCLUSION

Not all cats with heart disease

will develop clinical signs. Treatment

goals for feline HCM aimed to

controlling heart rate, alleviating

pulmonary congestion, removing

pleural fluid (if present), and

decreasing

the

likelihood

of

thromboembolism

or

saddle

thrombus. Echocardiography remains

the gold standard for diagnosis of

HCM in cats.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to

thank to Dr. Khor Kuan Hua as the

supervisor,

staff

of

University

Veterinary Hospital, Universiti Putra

Malaysia, and DVM Class of 2015

Universiti Putra Malaysia.

REFERENCES

Godiksen, M., Granstrm, S., Koch, J.,

&

Christiansen,

M.

(2011).

Hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy

in

young Maine Coon cats caused by

the p.A31P cMyBP-C mutation - the

clinical significance of having the

mutation. Acta Vet Scand Acta

Veterinaria Scandinavica, 53:7, 7-7.

doi:10.1186/1751-0147-53-7

Fuentes, V. (2010). Chapter 25:

Feline cardiomyopathy. In BSAVA

manual

of

canine

and

feline

cardiorespiratory medicine (2nd ed.,

pp. 229-230). Quedgeley: British

Small Animal Veterinary Association.

Jensen,

A.

(2007).

Feline

Hypertrophic

Cardiomyopathy.

Retrieved November 11, 2015, from

http://zimmerfoundation.org/sch/ajd.html

Smith SA, Tobias AH, Jacob KA, Fine

DM,

Grumbles

PL.

Arterial

thromboembolism

in cats: Acute

crisis in 127 cases (1992-2001) and

long-term management with low

dose aspirin in 24 cases. J Vet Intern

Med. 2003;17(1) :73-83.

Stokhof

AA.

Pathophysiology,

diagnosis, and results of treatment in

feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Proceedings E.S.V.I.M. 1996: 38-41.

Pace, C. (2011). Feline Hypertrophic

Cardiomyopathy. 2(2), 68-73.

Payne, J., Borgeat, K., Connolly, D.,

Boswood, A., Dennis, S., Wagner,

Fuentes,

V.

(2013).

Prognostic

Indicators in Cats with Hypertrophic

Cardiomyopathy.

Journal

of

Veterinary Internal Medicine J Vet

Intern Med, 1427-1436

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- (N) Parasitic GastroenteritisDokument2 Seiten(N) Parasitic GastroenteritisLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breeding of Genetic Parasitic ResistanceDokument2 SeitenBreeding of Genetic Parasitic ResistanceLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathophysiology of The RabiesDokument2 SeitenPathophysiology of The RabiesLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diseases With Discoloured Urine & AnaemiaDokument3 SeitenDiseases With Discoloured Urine & AnaemiaLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Equine Physical ExaminationDokument2 SeitenEquine Physical ExaminationLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Production DiseasesDokument4 SeitenProduction DiseasesLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Systems of Weights & MeasuresDokument2 SeitenSystems of Weights & MeasuresLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urinary Bladder Drugs and+their+Mechanisms+of+ActionDokument1 SeiteUrinary Bladder Drugs and+their+Mechanisms+of+ActionLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aquatic NotesDokument1 SeiteAquatic NotesLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- VirologyDokument6 SeitenVirologyLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mortality in Young ChicksDokument2 SeitenMortality in Young ChicksLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aquatic DiseasesDokument5 SeitenAquatic DiseasesLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beef Cattle ClassificationDokument51 SeitenBeef Cattle ClassificationLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abortion Disease in RuminantDokument3 SeitenAbortion Disease in RuminantLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renal DiseaseDokument9 SeitenRenal DiseaseLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- RabiesDokument5 SeitenRabiesLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- AKI N CKDDokument1 SeiteAKI N CKDLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diseases With Discoloured Urine & AnaemiaDokument3 SeitenDiseases With Discoloured Urine & AnaemiaLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ii. Poor Exercise Tolerance Ii. PalpationDokument14 SeitenIi. Poor Exercise Tolerance Ii. PalpationLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occurrence of Salmonella Spp. and E. Coli Isolates From Peridomestic Cockroaches (Periplaneta Americana) and Their Antibiotic Susceptibility PatternsDokument2 SeitenOccurrence of Salmonella Spp. and E. Coli Isolates From Peridomestic Cockroaches (Periplaneta Americana) and Their Antibiotic Susceptibility PatternsLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zoonotic DiseasesDokument5 SeitenZoonotic DiseasesLeyana AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Communication Scenarios PDFDokument1.052 SeitenCommunication Scenarios PDFDr AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monograph On Lung Cancer July14Dokument48 SeitenMonograph On Lung Cancer July14PatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: BIOLOGY 9700/21Dokument16 SeitenCambridge International AS & A Level: BIOLOGY 9700/21Rishi VKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fact Sheet YaconDokument2 SeitenFact Sheet YaconTrilceNoch keine Bewertungen

- CCCF - 2012 - EN Prevention and Reduction PDFDokument178 SeitenCCCF - 2012 - EN Prevention and Reduction PDFdorinutza280Noch keine Bewertungen

- Laporan Kasus Per Gol Umur Feb 2023Dokument7 SeitenLaporan Kasus Per Gol Umur Feb 2023Akreditasi UKPNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anger: Realized By: Supervised byDokument15 SeitenAnger: Realized By: Supervised byChahinaz Frid-ZahraouiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vijayalakshmi MenopauseDokument7 SeitenVijayalakshmi MenopauseakankshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Secrets of Hunza WaterDokument3 SeitenThe Secrets of Hunza Wateresmeille100% (2)

- Understanding Cancer Treatment and OutcomesDokument5 SeitenUnderstanding Cancer Treatment and OutcomesMr. questionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benign Paratesticlar Cyst - A Mysterical FindingDokument2 SeitenBenign Paratesticlar Cyst - A Mysterical FindingInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypernatremia NEJM 2000Dokument8 SeitenHypernatremia NEJM 2000BenjamÍn Alejandro Ruiz ManzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Additional Notes On ShockDokument3 SeitenAdditional Notes On ShockSheniqua GreavesNoch keine Bewertungen

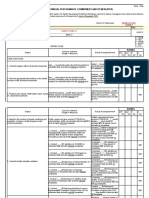

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledDokument12 SeitenIndividual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledTiffanny Diane Agbayani RuedasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Covid or PuiDokument45 SeitenCovid or PuiChristyl JoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opalescence Boost Whitening PDFDokument2 SeitenOpalescence Boost Whitening PDFVikas AggarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trial Kedah 2014 SPM Biologi K2 SkemaDokument14 SeitenTrial Kedah 2014 SPM Biologi K2 SkemaCikgu Faizal100% (1)

- Medication ErrorsDokument15 SeitenMedication ErrorsShubhangi Sanjay KadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- BourkeDokument8 SeitenBourkeMilan BursacNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMORC Index Degrees 5 and 6Dokument48 SeitenAMORC Index Degrees 5 and 6Alois HaasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mag MicroDokument67 SeitenMag MicroAneesh AyinippullyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neurogenic Shock in Critical Care NursingDokument25 SeitenNeurogenic Shock in Critical Care Nursingnaqib25100% (4)

- Breast LumpsDokument77 SeitenBreast LumpsAliyah Tofani PawelloiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Questions 2Dokument16 SeitenPractice Questions 2Jepe LlorenteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevod 41Dokument5 SeitenPrevod 41JefaradocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- REKAPITULASI PASIEN CA PENIS NewDokument51 SeitenREKAPITULASI PASIEN CA PENIS Newagus sukarnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WSH Guidelines Managing Safety and Health For SME S in The Metalworking Industry Final 2Dokument22 SeitenWSH Guidelines Managing Safety and Health For SME S in The Metalworking Industry Final 2Thupten Gedun Kelvin OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Assessment of The Autonomic Nervous System PDFDokument312 SeitenClinical Assessment of The Autonomic Nervous System PDFAndrija100% (1)

- CKD PrognosisDokument8 SeitenCKD PrognosisAlfred YangaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brain Edema XVI - Translate Basic Science Into Clinical Practice by Richard L Applegate, Gang Chen, Hua Feng, John H. ZhangDokument376 SeitenBrain Edema XVI - Translate Basic Science Into Clinical Practice by Richard L Applegate, Gang Chen, Hua Feng, John H. ZhangAjie WitamaNoch keine Bewertungen