Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Bencana

Hochgeladen von

zakyOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Bencana

Hochgeladen von

zakyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Dan Med Bul

June

DANISH MEDIC AL BULLE TIN

Nurse-administered early warning score system

can be used for emergency department triage

Dorthea Christensen1, Nanna Martin Jensen2, Rikke Maale1, Sren Steemann Rudolph1, Bo Belhage1 & Hans Perrild2

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Studies have shown that early warning

score systems can identify in-patients at high risk of catastrophic deterioration and this may possibly be used for an

emergency department (ED) triage. Bispebjerg Hospital has

introduced a multidisciplinary team (MT) in the ED activated by the Bispebjerg Early Warning Score (BEWS). The

BEWS is calculated on the basis of respiratory frequency,

pulse, systolic blood pressure, temperature and level of

consciousness. The aim of this study is to evaluate the ability of the BEWS to identify critically ill patients in the ED and

to examine the feasibility of using the BEWS to activate an

MT response.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: This study is based on an evaluation of retrospective data from a random sample of 300

emergency patients. On the basis of documented vital signs,

a BEWS was calculated retrospectively. The primary end

points were admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and

death within 48 hours of arrival at the ED. This study was

registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01243021).

RESULTS: A BEWS 5 is associated with a significantly increased risk of ICU admission within 48 hours of arrival

(relative risk (RR) 4.1; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.5-10.9)

and death within 48 hours of arrival (RR 20.3; 95% CI 6.960.1). The sensitivity of the BEWS in identifying patients

who were admitted to the ICU or who died within 48 hours

of arrival was 63%. The positive predictive value of the

BEWS was 16% and the negative predictive value 98% for

identification of patients who were admitted to the ICU or

who died within 48 hours of arrival.

CONCLUSION: The BEWS is a simple scoring system based

on readily available vital signs. It is a sensitive tool for detecting critically ill patients and may be used for ED triage

and activation of an MT response.

Emergency departments and acute admission units receive critically ill patients every day. Studies have shown

that rapid and effective initial treatment improves the

survival of these patients [1-3]. Critically ill patients

should therefore be identified quickly, so that relevant

treatment can be initiated without delay. Different

triage systems have been validated for use in emergency

departments (ED) and acute admission units [4-6]. A recent Danish survey found that no acute medical admis-

sion units in Denmark are using a validated triage system

[7].

Critical illness is frequently preceded by documented deterioration of physiological parameters

[8-10]. To identify high-risk patients, a number of scoring systems have been developed. These are based on

measurement of simple and readily available vital signs

such as respiratory rate, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, temperature and level of consciousness [11-14].

These systems are known as Early Warning Score systems (EWS). EWS have primarily been validated for inpatients. However, a few studies suggest that EWS may

also be used in the context of unselected medical admissions to identify patients with a high mortality in need of

intensive care [11, 12]. The sensitivity and specificity of

these systems have yet to be been examined.

To ensure a systematic triage and reception of critically ill patients in the ED, Bispebjerg Hospital has been

developing a system for the reception of such patients

since 2004. The system was termed emergency call (EC).

The EC consists of a multidisciplinary team which is activated on the basis of a triage system. The current triage

system was introduced in 2007 and relies on an EWSbased score, named Bispebjerg Early Warning Score

(BEWS) in combination with primary criteria as described below.

The aims of the present study are: To evaluate the

ability of BEWS to identify critically ill patients in the ED

and to examine the feasibility of BEWS as an activation

call trigger.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Bispebjerg University Hospital is a 600-bed urban teaching hospital serving a population of 400,000 (surgical)

and 270,000 (medical) citizens. A total of 38,000 patients

visit the ED annually. ECs are activated approximately 30

times a month for patients presumed to be critically ill.

On arrival, ED patients are evaluated by trained

triage nurses who have at least two years of experience

at our ED. They allocate all patients into one of three

categories (red, blue and white) based on the perceived

severity of their injuries or illnesses according to common regional guidelines [15] and the nurses clinical

judgment. The most severely ill and injured patients are

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

1) Department of

Anaesthesiology,

Bispebjerg Hospital,

and

2) Department of

Endocrinology and

Gastroenterology,

Bispebjerg Hospital

Dan Med Bul

2011;58(6):A4221

DANISH MEDIC AL BULLE TIN

Dan Med Bul

June

TABLE 1

Chart used for the calculation of the Bispebjerg

Early Warning Score.

Vital signs used for the

calculation of the score

are obtained when the

patient arrives at an

emergency department.

Each vital sign is assigned

a score of 0-3 points, and

scores are then

added to give a total

score. A score 5 triggers

an emergency call.

Points

3

Respiratory rate

9-14

15-20

21-30

> 30

Heart rate

40

41-50

51-100

101-110

111-130

> 130

Systolic blood pressure, mmHg

70

71-80

81-100

101-199

> 199

Temperature, C

35

35.1-36

36.1-38

38.1-39

> 39

Level of consciousness

Awake

Responds

to voice

Responds

to pain

Unresponsive

marked as red. These patients need immediate or

acute treatment.

In red patients, the triage nurses immediately

perform a secondary evaluation to assess whether an EC

is warranted. This is a two-step process. The first step

determines whether an EC is to be activated or not. This

assessment is performed on the basis of primary criteria, i.e. signs and symptoms presumed to be immediately life-threatening, like for instance upper airway obstruction, respiratory arrest or uncontrolled bleeding. If

no primary criteria are present, the evaluation continues to step two, where vital signs are obtained and

the BEWS is calculated (Table 1). Each vital sign is assigned a score of 0-3 points and the scores are then

added to yield a BEWS. A BEWS 5 triggers an EC. A

BEWS < 5 will normally not trigger the activation of an

EC unless the receiving nurse or physician has concerns

for the patient that are not expressed in steps one and

two. In this study, we have defined a critically ill patient

as a patient who is admitted to an intensive care unit

(ICU) within 48 hours of arrival at the ED or who dies

within 48 hours of arrival at the ED. See also Table 2.

TABLE 2

Definitions. We have defined a critically ill patient as a patient who is

admitted to an intensive care unit within 48 hr of arrival at an emergency

department or who dies within 48 hr of arrival at the emergency department.

Sensitivity

The ability of the BEWS to correctly classify critically ill patients, i.e. the prob-ability that a critically ill patient has a BEWS

5

Specificity

The ability of BEWS to correctly classify

patients who are not critically ill, i.e. the

probability that a patient who is not

critically ill has a BEWS < 5

Positive predictive value

The probability that a patient is critically ill

if the patient scores BEWS 5

Negative predictive value

The probability that a patient is not critically ill if the patient scores BEWS < 5

BEWS = Bispebjerg Early Warning Score.

To examine the ability of the BEWS to reliably identify critically ill patients at the ED, a random sample of

300 red patients visiting the ED in the period from 1

April to 30 September 2009 were evaluated. The sample

corresponds to a ninth of the population of red patients seen in the ED in this time period. These patients

are presumed to have a low prevalence of critical illness

even though they are marked as red.

Retrospective data were collected including demographic data and vital signs on arrival or within the first

15 minutes of arrival. A BEWS was calculated retrospectively for all patients on the basis of their vital signs

documented in the ED medical charts (by nurses or

phys-icians) or ambulance records. Patients were subdivided into two groups: BEWS 5 and BEWS < 5. A BEWS

5 could be found if a minimum of two vital signs were

documented. On the other hand, at least four vital signs

had to be documented to ensure that the BEWS < 5

(Table 1).

Patients with insufficient data were excluded from

the analysis. Patient outcome measures (death or ICU

admission) were obtained through the hospitals administrative system. No follow-up was made on patients

who were transferred to other hospitals and these patients are counted as survivors. This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01243021).

Data are primarily presented descriptively. Age is

reported as median and range. Relative risks (RR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

RESULTS

Among the 300 randomly selected red patients, 138

patients were excluded because of insufficient data. The

study thus included 162 red patients. A total of 24 patients from this randomly selected sample had activated

an EC.

Demographic data, BEWS and outcome for the

study population are summarized in Table 3.

Four patients were admitted to the ICU within 48

hours of arrival at the ED. Six patients died within 48

Dan Med Bul

DANISH MEDIC AL BULLE TIN

June

hours of arrival at the ED, including two of the patients

who were admitted to the ICU. This means that a total

of eight red patients (5%) met our definition of critical

illness.

A total of 32 patients had a BEWS 5, which was associated with a significantly increased risk of death

within 48 hours of arrival (RR 20.3; 95% CI 6.9-60.1), ICU

admission within 48 hours of arrival (RR 4.1; 95% CI 1.510.9) and of being critically ill according to our definition

(RR 6.8; 95% CI 3.3-13.8) compared to a BEWS < 5.

Table 4 shows the sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of BEWS in identifying death within 48 hours

of arrival, admission to ICU within 48 hours of arrival and

critical illness according to our definition. Among red

patients, a BEWS 5 identified 63% of the patients who

were admitted to the ICU within 48 hours of arrival or

who died within 48 hours of arrival, i.e. critically ill patients (sensitivity). The probability that a red patient

with a BEWS 5 would be admitted to the ICU within 48

hours of arrival or would die within 48 hours of arrival

was 16% (positive predictive value). At the same time,

there was a 98% probability that a red patient would

not be admitted to the ICU within 48 hours of arrival or

would not die within 48 hours of arrival (negative predictive value) if the BEWS < 5. As can be seen in Table 4,

the sensitivity and positive predictive value of the BEWS

in identifying admission to the ICU within 48 hours of arrival are lower than in identifying death within 48 hours

of arrival.

DISCUSSION

The BEWS is calculated on the basis of simple and readily available vital signs. The primary findings of this study

are that the BEWS can identify with great certainty

those patients who will be admitted to the ICU within 48

hours of arrival at the ED or who will die within 48 hours

of arrival at the ED. The BEWS is therefore a safe tool for

prioritizing resources to patients in need of rapid and intensive care.

In the literature, we have not been able to find a

practicable definition of critical illness. As the BEWS is to

be used for identification of critically ill patients on arrivall at the ED, we have chosen a rather narrow definition: a patient who is admitted to the ICU within 48

hours of arrival or who dies within 48 hours of arrival.

Naturally, this definition is arbitrary.

Our purpose was to exclude patients who deteriorated during admission, for example due to a hospitalacquired infection. Using this narrow definition, the

prevalence of critical illness in our study population

is low.

Studies have shown that mortality is significantly

higher among patients who are admitted to an ICU from

a hospital ward than among patients who are admitted

TABLE 3

Demographic data, Bispebjerg Early Warning Score and outcome for the study population.

Red patients included in the study

BEWS 5

(n = 32)

BEWS < 5

(n = 130)

total

(n = 162)

Proportion of men, %

50

49

49

Median age, years (range)

75 (39-92)

52 (2-98)

57 (2-98)

Presenting problem, n

Neurological deficit

19

25

Respiratory problem

18

19

37

Cardiac problem

48

48

Intoxication/poisioning

12

13

Abdominal pain

10

10

Bleeding/hypovolaemia

10

Allergic reaction

Hypoglycaemia

Fall trauma

Other reasons

Outcome, n

Deaths within 48 hr of arrival at the ED

ICU admissions within 48 hr of arrival at the ED

Critically ill patientsa

BEWS = Bispebjerg Early Warning Score; ED = emergency department; ICU = intensive care unit.

a) ICU admission within 48 hr of arrival at the ED or who die within 48 hr of arrival at the ED. Two of the

red patients admitted to the ICU also died within 48 hr of arrival at the ED.

to the ICU directly from the ED [3, 17]. To raise the quality of treatment given to critically ill patients on admission to the ED, early identification and rapid initiation of

appropriate treatment is therefore important. If a EWS

system is to be used for ED triage, it must be able to

identify critically ill patients with a high sensitivity and a

high negative predictive value.

We have shown that a BEWS 5 is associated with

a significantly increased risk of death within 48 hours of

arrival or admission to the ICU within 48 hours of arrival.

The BEWS is thus capable of dividing emergency patients

into low-risk patients and high-risk patients. We have

shown that the sensitivity of the BEWS in identifying

TABLE 4

Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of Bispebjerg Early Warning Score greater than or equal to

five in red patients.

Red patients included in the study (n = 162)

death within 48 hr

of arrival at the ED

ICU admission within 48 hr

of arrival at the ED

critial illnessa

Sensitivity, %

83

50

63

Specificity, %

83

81

82

Positive predictive value, %

16

16

Negative predic-tive value, %

99

98

98

ED = emergency department; ICU = Intensive care unit.

a) ICU admission within 48 hr of arrival at the ED or death within 48 hr of arrival at the ED.

DANISH MEDIC AL BULLE TIN

The Bispebjerg Early Warning Score is calculated using simple and readily

available vital parameters.

these critically ill patients is high. At the same time, the

negative predictive value is also high, and, consequently,

so is the risk of a patient being critically ill if the BEWS is

< 5. The BEWS is therefore a safe tool for ED triage.

As resources in EDs are limited, a triage system also

needs to have an acceptable specificity and positive predictive value in order to help prioritize the provision of

rapid and competent care to the patients who need it

the most. This is particularly true if the system is used to

direct a considerable amount of extra resources to a

particular group of patients, as is the case at Bispebjerg

Hospital. The specificity of the BEWS is high and there is

therefore a high probability that a person who is not

critically ill according to our definition will have a BEWS

< 5 and therefore will not activate a multidisciplinary

team response. The relatively low positive predictive

value of the BEWS among red patients must be perceived in the light of the low prevalence of critical illness

among the red patients and our rather narrow definition of critical illness.

Developing a triage system that is both safe and ensures a rational use of the multidisciplinary team has

been an ongoing process at our ED since 2004. Before

we introduced our BEWS system in 2007, ECs were triggered by medical emergency team criteria (MET) [17]

a simple system triggered when a single extreme

physiological value was reached. However, an evaluation

of the MET showed that they were inexpedient for the

activation of ECs and that, in turn, motivated the development of the BEWS [17].

Studies of other EWS systems have shown that

mortality rises with rising EWS [11-13]. Selecting a

higher cut-off value for activation of ECs, e.g. BEWS 6,

would thus be expected to raise the specificity and positive predictive value, which means that fewer, but more

severely ill patients would be identified. However, this

would be at the expense of more false negatives, i.e.

lower sensitivity and negative predictive value. The im-

Dan Med Bul

June

proved resource utilization must be weighed against the

risk of insufficient and delayed care of critically ill patients who are misjudged by the system (false negatives). Due to poor documentation of vital signs in the

ED charts, this study is unable to estimate the effect of

raising the cut-off value for activation of ECs to e.g.

BEWS 6.

In our opinion, the finding that 16% of red patients with a BEWS 5 are admitted to the ICU within 48

hours of arrival at the ED or die within 48 hours of arrival

at the ED makes the BEWS a feasible tool for activation

of a multidisciplinary team response. Instead of raising

the cut-off value for activation of an EC, we have tried to

rationalize the use of resources by introducing two

levels of EC, EC I and II, where the number and competencies of the team members depend on the BEWS

score level [18].

A limitation of this study is that many patients had

to be excluded because of insufficient documentation of

vital signs, which made retrospective calculation of a

BEWS impossible. We suspect that the excluded patients

comprise a smaller proportion with BEWS 5 than the

patients included (i.e. when patients are obviously not

very ill, the ED nurses do not measure as many vital

signs). This introduced a risk of selection bias which

would lead to overestimation of the prevalence of critical illness among red patients. This will affect the

estimated sensitivity, specificity and predictive values

in the study population.

We have evaluated the compliance with our triage

system, i.e. documentation of vital signs and calculation

of BEWS, and concluded that our triage system is not yet

fully implemented. Poor documentation of vital signs is,

however, not only a problem at Bispebjerg Hospital, but

is known to be a wide-spread issue [14, 19]. The reasons

why documentation of vital signs is poor are probably

many: Work pressure, lack of knowledge about the importance of vital signs in the prediction of high-risk patients and overreliance on own experience and clinical

judgment are possible explanations. Implementation of

the BEWS will continue to play an important role in the

ongoing process of improving the quality of our ED triage.

In our opinion, it is important that triage is performed on the basis of an objective and validated system in order to ensure uniformity and to achieve a high

level of quality. Like previous studies [11, 12], our study

indicates that EWS systems are safe triage tools in EDs

and acute medical admission units. A recent survey [1]

claimed that no Danish acute medical admission units

use validated triage systems and that medical triage is

primarily based on clinical judgment. The potential for

the implementation of BEWS or other EWS-based systems in Danish EDs and acute medical admission units is

thus considerable.

Dan Med Bul

June

CORRESPONDENCE: Dorthea Christensen, Akacievej 18, st. th., 2830 Virum,

Denmark. E-mail: dortheafc@gmail.com

ACCEPTED: 27 October 2010

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: None

LITERATURE

1. Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA et al. Effects of a medical emergency

team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac

arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ 2002;324:387-90.

2. Goldhill DR, White SA, Sumner A. Physiological values and procedures in

the 24 h before ICU admission from the ward. Anaesthesia 1999;54:52934.

3. Parkhe M, Myles PS, Leach DS et al. Outcome of emergency department

patients with delayed admission to an intensive care unit. Emerg Med

2002;14:50-7.

4. Cooke MW, Jinks S. Does Manchester triage system detect critically ill? J

Accid Emerg Med 1999;16:179-81.

5. Wuerz RC, Milne LW, Eitel DR et al. Reliability and validity of a new fivelevel triage instrument. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:236-42.

6. Eitel DR, Travers DA, Rosenau AM et al. The emergency severity index

triage algorithm version 2 is reliable and valid. Acad Emerg Med

2003;10:1070-80.

7. Brabrand M, Folkestad L, Hallas P. Visitation og triage af akut indlagte

medicinske patienter. Ugeskr Laeger 2010;22:1666-8.

8. Schein RM, Hazday N, Pena M et al. Clinical antescendent to in-hospital

cardiopulmonary arrest. Chest 1990;98;1388-92.

9. Franklin C, Mathew J. Developing strategies to prevent inhospital cardiac

arrest: analyzing responses of physicians and nurses in the hours before

the event. Crit Care Med 1994;22:244-7.

DANISH MEDIC AL BULLE TIN

10. Buist MD, Jarmolowski E, Burton PR et al. Recognising clinical instability

before cardiac arrest or unplanned admission to intensive care. Med J Aust

1999;171:22-5.

11. Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P et al. Validation of a modified early

warning score in medicial admissions. Q J Med 2001;94:521-6.

12. Groake JD, Gallagher J, Stack J et al. Use of an admission early warning

score to predict patient morbidity and mortalitity and treatment success.

Emerg Med J 2008;25;803-6.

13. Goldhill DR, McNarry AF, Mandersloot G et al. A physiologically-based

early warning score for ward patients: the association between score and

outcome. Anaesthesia 2005;60:547-53.

14. Paterson R, MacLeod DC, Thetford D et al. Prediction of in-hospital

mortality and length of stay using an early warning scoring system: clinical

audit. Clin Med 2006;6:281-4.

15. Region Hovedstaden. Visitation, journalfring og journalaudit i somatiske

skadestuer. Tvrgende vejledning for de tidligere H:S Hospitaler.

Kbenhavn: Region Hovedstaden, 2008

16. Goldhill DR, Sumner A. Outcome of intensive care patients in a group of

British intensive care units. Crit Care Med 1998;26;1337-45.

17. Rudolph SF, Skousen MB, Isbye DI. The use of a physiological scoring

system in the emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med

2007;15:160-3.

18. Christensen D. Tvrfaglig teammodtagelse af kritisk syge patienter. Scand

Update Mag 2010;2:23-6.

19. Goldhill DR. The critically ill: following your MEWS. Q J Med 2001;94:50710.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Clinical case in the emergency room of a patient with an ischemic strokeVon EverandClinical case in the emergency room of a patient with an ischemic strokeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Esi Validacion EuropaDokument6 SeitenEsi Validacion EuropaPaullette SanjuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lectura 1 AfDokument10 SeitenLectura 1 AfCésar Alfonso Hernández NonajulcaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFDokument7 Seiten1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFBirhanu MuletaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Simple Clinical Score "TOPRS" To Predict Outcome in Pédiatrie Emergency Department in A Teaching Hospital in IndiaDokument6 SeitenA Simple Clinical Score "TOPRS" To Predict Outcome in Pédiatrie Emergency Department in A Teaching Hospital in IndiaRyl WonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Warning Score For Patient Safety Measures - Mohd Said NurumalDokument50 SeitenEarly Warning Score For Patient Safety Measures - Mohd Said NurumalAiko himeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accuracy of The Emergency Severity Index Triage Instrument For Identifying Elder Emergency Department Patients Receiving An Immediate Life-Saving InterventionDokument6 SeitenAccuracy of The Emergency Severity Index Triage Instrument For Identifying Elder Emergency Department Patients Receiving An Immediate Life-Saving InterventionRuly AryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- J 1553-2712 2011 01122 X PDFDokument8 SeitenJ 1553-2712 2011 01122 X PDFSriatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- f400 PDFDokument4 Seitenf400 PDFJoan ProcesoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PCT FeverDokument6 SeitenPCT FeverAndi BintangNoch keine Bewertungen

- 38 Hoot 2007Dokument9 Seiten38 Hoot 2007ARTZchebilNoch keine Bewertungen

- CMRP0218Dokument14 SeitenCMRP0218cherish60126Noch keine Bewertungen

- SedationDokument7 SeitenSedationAurora Violeta Zapata RuedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Published Article - EJKI Vol 1 No 3 (Desember 2013)Dokument5 SeitenPublished Article - EJKI Vol 1 No 3 (Desember 2013)TommysNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Padua2Dokument12 SeitenJurnal Padua2inayatul munawarohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petersen 2016Dokument6 SeitenPetersen 2016debbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of The SOFA Score To Assess The Incidence of Organ Dysfunction/failure in Intensive Care Units: Results of A Multicenter, Prospective StudyDokument8 SeitenUse of The SOFA Score To Assess The Incidence of Organ Dysfunction/failure in Intensive Care Units: Results of A Multicenter, Prospective StudybayuaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AppbjDokument6 SeitenAppbjGilang IrwansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idiopathic First Seizure in Adult Life: Who Be Treated?: ShouldDokument4 SeitenIdiopathic First Seizure in Adult Life: Who Be Treated?: ShouldJessica HueichiNoch keine Bewertungen

- PESI Critical Care 2005Dokument6 SeitenPESI Critical Care 2005Rocio Méndez FrancoNoch keine Bewertungen

- See Also Page 1013: ESS S OREDokument3 SeitenSee Also Page 1013: ESS S ORESundas EjazNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pediatric Early Warning System Score: A Severity of Illness Score To Predict Urgent Medical Need in Hospitalized ChildrenDokument8 SeitenThe Pediatric Early Warning System Score: A Severity of Illness Score To Predict Urgent Medical Need in Hospitalized ChildrenRavikiran SuryanarayanamurthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Simple Prognostic Score For Risk Assessment in Patients With Acute PancreatitisDokument6 SeitenA Simple Prognostic Score For Risk Assessment in Patients With Acute PancreatitisGeorgiana CrisuNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Early Warning System Improves Patient Safety and Clinical Outcomes in A Community Academic HospitalDokument9 SeitenAn Early Warning System Improves Patient Safety and Clinical Outcomes in A Community Academic HospitalAnasthasia hutagalungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admission Inferior Vena Cava Measurements Are Associated With Mortality After Hospitalization For Acute Decompensated Heart FailureDokument18 SeitenAdmission Inferior Vena Cava Measurements Are Associated With Mortality After Hospitalization For Acute Decompensated Heart FailurePuja Nastia LubisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Referensi 1Dokument5 SeitenReferensi 1emi nowweNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Warning System For PediatricsDokument15 SeitenEarly Warning System For PediatricsYulia DeriniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 019 - Ulil Chiqmatuss'diah - KMB 1Dokument4 Seiten019 - Ulil Chiqmatuss'diah - KMB 1Setiaty PandiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remote Patient Monitoring in Chronic Heart FailureDokument10 SeitenRemote Patient Monitoring in Chronic Heart FailureTony TuestaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CCM 45 10 2017 05 25 Zhang Ccmed-D-16-00678 sdc2Dokument6 SeitenCCM 45 10 2017 05 25 Zhang Ccmed-D-16-00678 sdc2denisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Search BMJ GroupDokument23 SeitenSearch BMJ GroupCharles BrooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emergency Physician Awareness of Prehospital ProceDokument8 SeitenEmergency Physician Awareness of Prehospital ProceNines RíosNoch keine Bewertungen

- S0196064413X00125 S0196064413010895 Main PDFDokument2 SeitenS0196064413X00125 S0196064413010895 Main PDFwilmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijph 41 2 63Dokument7 SeitenIjph 41 2 63Asry AchyyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijph 41 2 63 PDFDokument7 SeitenIjph 41 2 63 PDFAsry AchyyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emergency Referrals PDFDokument8 SeitenEmergency Referrals PDFEngidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis TopicsDokument14 SeitenThesis TopicskiranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prospective External Validation of An Accelerated (2-h) Acute Coronary Syndrome Rule-Out Process Using A Contemporary Troponin AssayDokument5 SeitenProspective External Validation of An Accelerated (2-h) Acute Coronary Syndrome Rule-Out Process Using A Contemporary Troponin AssayHidayadNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6Dokument8 Seiten6yoghaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definisi Dan Kriteria Terbaru Diagnosis Sepsis Sepsis-3Dokument5 SeitenDefinisi Dan Kriteria Terbaru Diagnosis Sepsis Sepsis-3nindyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Missed Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis in The Emergency Department by Emergency Medicine and Neurology ServicesDokument7 SeitenMissed Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis in The Emergency Department by Emergency Medicine and Neurology ServicesReyhansyah RachmadhyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sepsis 2019Dokument12 SeitenSepsis 2019EviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Systematic Triage in The Emergency Department Using The Australian National Triage Scale: A Pilot ProjectDokument5 SeitenSystematic Triage in The Emergency Department Using The Australian National Triage Scale: A Pilot ProjectanggitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Prediction of Severity StrokeDokument11 SeitenEarly Prediction of Severity StrokeainihanifiahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aabsrtract, Methode, LimitationDokument3 SeitenAabsrtract, Methode, LimitationLivia BaransyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- ResearchDokument11 SeitenResearchIMNG_PDFNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oncology Nursing Trends and Issues 2Dokument6 SeitenOncology Nursing Trends and Issues 2DaichiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESI ER CompleteDokument45 SeitenESI ER Completetammy2121Noch keine Bewertungen

- Is It Safe To Discharge Intussusception Patients After Successful Hydrostatic Reduction?Dokument5 SeitenIs It Safe To Discharge Intussusception Patients After Successful Hydrostatic Reduction?DaGiTrVel'zNoch keine Bewertungen

- Triage System in Accident and EmergencyDokument8 SeitenTriage System in Accident and EmergencySherry SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay-The Need To Look Beyond Traditional Risk Factors in Medical Diagnoses Diviyashree KasiviswanathanDokument12 SeitenEssay-The Need To Look Beyond Traditional Risk Factors in Medical Diagnoses Diviyashree Kasiviswanathanapi-672608340Noch keine Bewertungen

- RoleDokument8 SeitenRolePutra EkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Independent Risk Factor ShiveringDokument9 SeitenIndependent Risk Factor ShiveringAnonymous r2nNdvvweNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sepsis Screen Treatment AlgorithmDokument66 SeitenSepsis Screen Treatment AlgorithmcindythungNoch keine Bewertungen

- JurnalDokument11 SeitenJurnalStefany SahurekaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Treatment Outcomes of Hypetensive Emergency Patients Results From The Hypertension Registry Program in Northeastern ThailandDokument7 SeitenClinical Treatment Outcomes of Hypetensive Emergency Patients Results From The Hypertension Registry Program in Northeastern ThailandClaudia FreyonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JCM 07 00333 PDFDokument10 SeitenJCM 07 00333 PDFAndi Utari Dwi RahayuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emergency Severity Index LEC MLT 2 10 24Dokument27 SeitenEmergency Severity Index LEC MLT 2 10 24SJane FeriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesth Analg-1970-ALDRETE-924-34 PDFDokument11 SeitenAnesth Analg-1970-ALDRETE-924-34 PDFYudiSiswantoWijaya100% (2)

- Delirium in Mechanized PacientsDokument10 SeitenDelirium in Mechanized PacientsGabrielSteffenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Konsep Dasar Triage Instalasi Gawat DaruDokument17 SeitenKonsep Dasar Triage Instalasi Gawat DaruJulia Dewi Eka GunawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESC Heart FailureDokument36 SeitenESC Heart FailurezakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clark 2014Dokument16 SeitenClark 2014zakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality Indicators For The Assessment and Management of Pain in The Emergency Department: A Systematic ReviewDokument12 SeitenQuality Indicators For The Assessment and Management of Pain in The Emergency Department: A Systematic ReviewzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Care of Children in Pain Admitted To A Pediatric Emergency and Urgency UnitDokument5 SeitenCare of Children in Pain Admitted To A Pediatric Emergency and Urgency UnitzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- HWSP ScholarshipDokument1 SeiteHWSP ScholarshipzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Self-Care HFDokument12 SeitenRole of Self-Care HFzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESC Heart FailureDokument36 SeitenESC Heart FailurezakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes Self ManagementDokument12 SeitenDiabetes Self ManagementzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- IPAQ English Self-Admin ShortDokument3 SeitenIPAQ English Self-Admin ShortDavid Curtis MintahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effective Interventions For Improving Self Care in Patients 092314Dokument15 SeitenEffective Interventions For Improving Self Care in Patients 092314zakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Web Version Hypoglycemia QnaireDokument1 SeiteWeb Version Hypoglycemia QnairezakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- DMDokument2 SeitenDMzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vba 21 0960e 1 AreDokument3 SeitenVba 21 0960e 1 ArezakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recognition of PerceptorDokument7 SeitenRecognition of PerceptorzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypoglycemia QuestionnaireDokument2 SeitenHypoglycemia QuestionnairezakyNoch keine Bewertungen

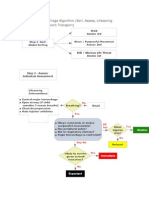

- Mass Casualty Triage AlgorithmsDokument7 SeitenMass Casualty Triage AlgorithmszakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Watson NewDokument20 SeitenWatson NewzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The One Minute PreceptorDokument3 SeitenThe One Minute PreceptorzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Web Version Hypoglycemia QnaireDokument1 SeiteWeb Version Hypoglycemia QnairezakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mass Casualty Triage AlgorithmsDokument7 SeitenMass Casualty Triage AlgorithmszakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Do Not Resuscitate Orders and Ethical Decisions in A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in A Muslim CommunityDokument5 SeitenDo Not Resuscitate Orders and Ethical Decisions in A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in A Muslim CommunityzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- One Minute To Be PreceptorDokument6 SeitenOne Minute To Be PreceptorzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Minute PreceptorDokument8 Seiten5 Minute Preceptorapi-323449274Noch keine Bewertungen

- Readness EBPDokument10 SeitenReadness EBPzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- FJ Me Malik RevisedDokument5 SeitenFJ Me Malik RevisedzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mastering The Preceptor RoleDokument12 SeitenMastering The Preceptor RolezakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recognition of PerceptorDokument7 SeitenRecognition of PerceptorzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mercury Column SphygmomanometerDokument2 SeitenThe Mercury Column SphygmomanometerzakyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music Therapy in Nursing HomesDokument7 SeitenMusic Therapy in Nursing Homesapi-300510538Noch keine Bewertungen

- Paper Roleplay Group 3Dokument7 SeitenPaper Roleplay Group 3Endah Ragil SaputriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coping With CrossdressingDokument43 SeitenCoping With Crossdressingjodiebritt100% (5)

- Riddhi Perkins College ResumeDokument3 SeitenRiddhi Perkins College Resumeapi-3010303820% (1)

- Enfermedades Productos o AfeccionesDokument9 SeitenEnfermedades Productos o AfeccionesHumberto Colque LlaveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCPDokument14 SeitenNCPclaidelynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction of Magic Rose UpDokument21 SeitenIntroduction of Magic Rose UpanggrainiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oet Test Material: Occupational English Test Reading Sub-Test NursingDokument13 SeitenOet Test Material: Occupational English Test Reading Sub-Test NursingRyu Tse33% (3)

- Apraxia TreatmentDokument80 SeitenApraxia Treatmentaalocha_25100% (1)

- Quantifying The Health Economic Value AsDokument1 SeiteQuantifying The Health Economic Value AsMatiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHCCCS015 Student Assessment Booklet Is (ID 97088) - FinalDokument33 SeitenCHCCCS015 Student Assessment Booklet Is (ID 97088) - FinalESRNoch keine Bewertungen

- HEX PG SyllabusDokument124 SeitenHEX PG SyllabusJegadeesan MuniandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCIT 1408 Applied Human Anatomy and Physiology II - Urinary System Chapter 25 BDokument50 SeitenSCIT 1408 Applied Human Anatomy and Physiology II - Urinary System Chapter 25 BChuongNoch keine Bewertungen

- GMO Pro Arguments (Gen-WPS OfficeDokument4 SeitenGMO Pro Arguments (Gen-WPS OfficeFranchesca RevelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 NCCAOM Herbal Exam QuestionsDokument10 Seiten2012 NCCAOM Herbal Exam QuestionsElizabeth Durkee Neil100% (2)

- HED 2007 Cellular Molecular, Microbiology & GeneticsDokument16 SeitenHED 2007 Cellular Molecular, Microbiology & Geneticsharyshan100% (1)

- Nightinale Paper 400 WordsDokument4 SeitenNightinale Paper 400 WordsAshni KandhaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- JC-2 Tutorial-1 Immunology Practice MCQ'sDokument14 SeitenJC-2 Tutorial-1 Immunology Practice MCQ'shelamahjoubmounirdmo100% (5)

- Expression of Interest - Elective Placement For Medical StudentsDokument2 SeitenExpression of Interest - Elective Placement For Medical Studentsfsdfs100% (1)

- Aerodrome Emergency Plan PresentationDokument22 SeitenAerodrome Emergency Plan PresentationalexlytrNoch keine Bewertungen

- QB BT PDFDokument505 SeitenQB BT PDFنيزو اسوNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infective Endocarditis (IE)Dokument76 SeitenInfective Endocarditis (IE)Mahesh RathnayakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR-Cas-based Methods For Genome EngineeringDokument9 SeitenZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR-Cas-based Methods For Genome EngineeringRomina Tamara Gil RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Tobacco Smoking Among Third Year Student Nurse in The University of LuzonDokument6 SeitenThe Effect of Tobacco Smoking Among Third Year Student Nurse in The University of LuzonNeil Christian TadzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Five Elements Chart TableDokument7 SeitenFive Elements Chart TablePawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR Bagus Ari - Cardiogenic Shock KuliahDokument28 SeitenDR Bagus Ari - Cardiogenic Shock KuliahrathalosredNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypnosis For Irritable Bowel SyndromeDokument3 SeitenHypnosis For Irritable Bowel SyndromeImam Abidin0% (1)

- Full Text of RA 7719Dokument4 SeitenFull Text of RA 7719camz_hernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAN Party Skate Park by Shane Jesse ChristmassDokument91 SeitenLAN Party Skate Park by Shane Jesse ChristmassPatrick TrottiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal SociologyDokument53 SeitenCriminal SociologyJackielyn cabayaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (81)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossVon EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (6)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDVon EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeVon EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityVon EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (26)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionVon EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (404)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (42)

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearVon EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (23)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsVon EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaVon EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsVon EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityVon EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryVon EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (44)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Von EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (110)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerVon EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (392)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsVon EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlVon EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (58)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingVon EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1138)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningVon EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsVon EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (170)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessVon EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (328)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsVon EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)