Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

Hochgeladen von

Nicolas ObiglioCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

Hochgeladen von

Nicolas ObiglioCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy

Volume 2

Issue 1 Journal of Clinical Art Therapy

Article 5

2014

Clinical Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy: An

Integration of Practices

Debra Linesch

Loyola Marymount University, debra.linesch@lmu.edu

Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat

Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Other Languages,

Societies, and Cultures Commons

Recommended Citation

Linesch, D. (2014). Clinical Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy: An Integration of Practices.

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, 2(1), , retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/

iss1/5

This Peer Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marital and Family Therapy at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount

University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Clinical Art Therapy by an authorized administrator of Digital

Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact digitalcommons@lmu.edu.

Linesch: Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

Abstract

Hebrew calligraphy is explored as a possible link between the image-based practices

of clinical art therapy and the transcendent potential of the faith-based practices of

Judaism. An art therapist attempts to integrate decades of clinical experience with current

investigations into a traditional discipline. The project, including art making and meaning

making, results in a discussion of important ways that clinical practice and spiritual

explorations can be unified and mutually enhancing.

Published by Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School, 2014

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, Vol. 2 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 5

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

Hebrew Calligraphy and Clinical Art Therapy:

An Integration of Practices

This paper explores the process of integrating two apparently disparate practices: the

first, clinical art therapy, a practice of psychotherapy that centralizes image making; and the

second, Hebrew calligraphy, a faith-based practice that renders biblical script to access the

transcendent. The first of these two practices is rooted in theories of psychotherapy that

understand that internal human experiences can be accessed in dialogue and in relationship and

that self-expression is inherently healing. The second of these two practices is rooted in a much

longer history of human experience understood as a spiritual quest for meaning and or

connection.

The exploration is based on my three decades of professional engagement in the practice

of clinical art therapy, which has continuously affirmed the power of imagery as meaning

making, albeit in the service of psychological and emotional self-awareness. In more recent

years I have recognized potential limitations of the practice and its theoretical underpinnings in

psychoanalysis, humanism, and family systems theory as unable to integrate and appreciate

spiritual and/or religious yearnings. It is the intent of this project to explore and extend the

possibilities of integration between the theoretically bound practices of clinical art therapy and

the lived experiences of one of its practitioners. The work is my personal narrative, and I

acknowledge its specificity as the ponderings of an urban, educated, middle-class Jewish woman

in the seventh decade of life.

Informing Literature

A growing body of literature supports this attempt at integration. Informing this paper

are art therapists (Allen, 2005; Farrelly-Hansen, 2001; Horovitz, 2002; McNiff, 2004; B. Moon,

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/5

Linesch: Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

1992) who have written extensively about the relationship between art, spirituality, and

wholeness. Their perspectives suggest that the spiritual life of the art therapy clinician is a

significant component of the healing relationship. Also informing this paper is a body of

literature from a variety of religious traditions that supports the inclusion of imagery making as a

spiritual practice (Adams, 2006; Kao et al., 2014; Milgrom, 1992; Wuthnow, 2006). These

authors speak from the Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish, and Christian traditions about the curative

relationship between prayer/meditation and art making.

As a psychotherapist for over thirty years, I have lived my life mostly in the first practice,

living within and informed by my clinical work. My education, my professional training, and

my values have been shaped by the cultural norms of psychoanalysis, humanism, and family

systems theories. I have believed that I can best be of help to others and to myself through

exploration, explanation, and understanding. As an art therapist I have come to rely on the

image making process as the pathway to explore, explain, and understand. As a university

professor I have been indoctrinated to accept the disciplinary silos that academia has created to

separate the study of psychology from the study of theology. Consequently, I have been

educated out of the faith tradition in which I was raised and denied its riches and healing

opportunities.

In 2002, I wrote about my dilemma:

As a young person I felt marginalized by my religion, unwelcome as a woman into the

Conservative/Orthodox traditions of my eastern European grandparents and Canadian

parents and uneducated into the language and rituals that were themselves transitioning

from shtetl to suburb. Like many Jews of my generation, I looked outside Judaism for my

Published by Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School, 2014

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, Vol. 2 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 5

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

identity to the university for education, to psychotherapy for personal and professional

growth, and to the arts for self-expression. (Linesch as cited in Rosove, 2002, p. 34)

The following year I began the long journey of attempting to link all that I had come to believe

about image based psychotherapy with all that I yearned for from my faith tradition.

My first adult foray into the Jewish tradition began with Torah study, a process I could

easily access because of my education and my proclivity to understand metaphor. I started

inviting peers, friends, and co-religionists to engage in image-making as a process of studying

sacred text. I based this innovative experiment on my art therapy appreciation for images as

constructs of meaning and emotion. This work and the enthusiastic responses of both artists and

non-artists affirmed that connections could be made between faith-based practices (my new

territory) and clinical art therapy practices (my old territory). I continued exploring, and I

published two books (Linesch, 2013; Linesch & Stettin, 2009) about this work. I thought I was

done.

I became aware that the study of Torah, as central as it is to Jewish life, was not the

primary experience I was seeking. What I wanted to understand, engage in, and integrate was

the experience of prayer. Could I find a way to extend the practices of clinical art therapy into

my faith-based explorations to encompass more than text study and possibly find pathways for

engagement with the transcendent?

I found inspiration for this possibility in several places; I found it in the literature I

accessed in diverse fields (Allen, 2005; Cameron, 1992; Milgrom, 1992; Wuthnow, 2006), and I

found it in art. The work of the twentieth century printmaker Ben Shahn, in particular, moved

me to explore the process of rendering the ancient script. His work, as illustrated in Figure 1,

incorporated idiosyncratic calligraphy as personal expression. In this print, Variation of Psalm

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/5

Linesch: Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

133, Shahn has reproduced sacred text and reinterpreted it with additional contextualizing

imagery, a process that inspired the work I would do.

Figure 1. Variation of Psalm 133.

Shahn (1963) referenced Rabbi Abulafia, the great mystic, who identified the transcendent power

of Hebrew letters:

In letters were to be found the deepest mysteries, that in the contemplation of the shapes

the devout might ascend through every purer, more abstract levels of experience to

achieve at last the ultimate, ineffable abstraction of union with his God. (p. 5)

I became aware of the history of Hebrew calligraphy as a pathway to the mystical and found

support for the intention to render the ancient letters as a spiritual practice in the work of Rabbi

Lawrence Kushner (1975). Kushner explains the mystical connections:

The OTIYOT (letters of the Hebrew alphabet) are more than just the signs for sounds.

They are symbols whose shape and name, placement in the alphabet, and words they

begin put them each in the center of a unique spiritual constellation. They are themselves

holy. They are vessels carrying within the light of the Boundless One. (p. 17)

Published by Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School, 2014

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, Vol. 2 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 5

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

6

Inquiry Process

Although I did not intend this project to be a formal research inquiry, I understand its

affinities with the methodology of autoethnography (Ellis, Adams, & Bochner, 2011), a research

process that embraces product and process simultaneously. Looking for a disciplined and

rigorous art-based approach, I devised a multi-step investigation that I hoped would link

everything I held as true from my clinical art therapy practice with everything I wanted from my

faith tradition. I divided the process into seven steps: the first three extracted from my faith

based practices and the final four extracted from clinical art therapy practices.

1. Study and practice Hebrew calligraphy

2. Study and practice the daily prayers of traditional Judaism

3. Select liturgical fragments as a meditation

4. Render the fragments for 40 days

i. First using pen and ink Hebrew calligraphy

ii. Second embellishing the Hebrew with other materials

5. Examine the imagery

6. Explore the process with others

7. Find meanings

Steps 1 and 2

I found help for the first two steps in my own communities, both Jewish and Jesuit; Rabbi

Anne Brener (Academy of Jewish Religion) helped me study and extract liturgical fragments

from the traditional daily prayers, and Rabbi Ilana Schacter (Loyola Marymount University)

patiently taught me Hebrew calligraphy.

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/5

Linesch: Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

Step 3

I paid careful attention to the internal stirrings that I experienced as I studied and repeated

the daily liturgy. I noticed in particular the ideas of vulnerability expressed in the nighttime

prayers, the expression of gratitude in the morning service, and the reminders to stay connected

in the mid-day liturgy. Selecting these three inner states as manifestations of my own

experiences, I crafted a daily meditation/rendering (see Figure 2).

...before bed (MAARIV)

Grant that we may lie down in peace, Eternal One, and awaken us to life.

(reflecting my)

VULNERABILITY

...arising (SHACHARIT)

I offer thanks before you, eternal One, for You have mercifully restored my soul within me.

(reflecting my)

GRATITUDE

...mid-afternoon (MINCHA)

%

Happy are those who dwell in Your house; they are continually praising You.

(reflecting my)

PRESENCE

Figure 2. Liturgical scaffold for calligraphic meditation.

Step 4

The fourth step was the biggest challenge, involving the migration of art therapy practices

(including materials, structure, and prompts). I established a daily routine that involved starting

with a simple rendering of the liturgical scaffold, the three fragments in Figure 2. I decided that I

would do this work for 40 days, reminiscent of Moses experience at Sinai. I collected a variety

Published by Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School, 2014

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, Vol. 2 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 5

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

of inks and pens that I enjoyed using and augmented the supplies with metallic paints and the

loosely woven cheesecloth that had become important in my Torah study imagery (Linesch,

2013), symbolically representing illumination and revelation. The use of gold, silver, and copper

pigments was new in my imagery and tied to the sense I had that these elemental and glorious

colors were appropriate to the explorations in which I was engaging. The cheesecloth with its

capacity to hold dye and to be unwoven and reconfigured offered an exquisite symbol for the

fluid and shifting appearance and disappearance of revelation. I was not sure how I was going to

utilize the materials, but I trusted the process and decided that the pen and ink calligraphy would

invite the other materials to create embellishments and extend meanings.

Step 5

After completing the 40-day engagement in image making, I began a disciplined process

of examining the imagery. I looked at shape, form, color and texture, and I created journal

entries that were reminiscent of the kinds of conversations I encouraged clients in clinical art

therapy to have about their imagery. Eight examples of the imagery are presented accompanied

by text that summarizes my observations and understandings (see Figures 3-10).

Figure 3. Second day rendering.

On the second day I realized that

the metallic colors of gold, silver,

and copper were my new palette.

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/5

Figure 4. Sixth day rendering.

On the sixth day I began incorporating the

deconstructed cheesecloth in shapes that

shadowed the text.

Linesch: Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

Figure 5. Eleventh day rendering.

Figure 6. Twelfth day rendering.

On the eleventh day I began dying

the deconstructed cheesecloth in the

metallic colors of my palette. I found

the covering and illuminating of the

text very provocative.

Figure 7. Fifteenth day rendering.

On the fifteenth day I realized that

the colors that contextualized the

text were the colors that enlivened

and spirited the emerging figure.

On the twelfth day I witnessed

the appearance of a self-image

and found delight in the dancing,

stretching, emerging woman.

Figure 8. Twenty-sixth day rendering.

On the twenty-sixth day I could no longer

pretend that the experience I was having in

rendering the text was not reflected in the

energized movement of the decidedly selfrepresentative figure.

Published by Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School, 2014

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, Vol. 2 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 5

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

Figure 9. Twenty-ninth day rendering.

On the twenty-ninth day the

revelations I was witnessing scared

me and I created a messy blotch.

10

Figure 10. Thirty-eighth day rendering.

On the thirty-eighth day I could no longer

avoid direct self-representation and

included self-portraiture encased in dyed

cheesecloth as curtains that frame the

liturgical fragments.

Step 6

I shared the imagery with a variety of family members, colleagues, and trusted friends.

With their input I began to understand what I had done. The conversations helped me see that

through the construction and repetition of the art based ritual, I had learned to know and become

intimate with the liturgy. Words that I had selected from my tradition became familiar, personal,

and practiced. The observations of others helped me see how I had allowed myself to play with

creative self-expression and how the embellished texts had become increasingly self-reflective.

It became apparent to me that as I had moved through the 40-day meditation, I had found my

own center in the prayer process and had learned something that now seems so simple and

fundamental. The art process had helped me inhabit the liturgy and experience the kind of

authentic engagement the text alone had not.

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/5

10

Linesch: Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

11

Findings and Meanings

Just as image making enhances the process of self-awareness and insight in the practice

of clinical art therapy, image making enhances the process of spiritual connectedness in a faithbased practice. Just as I have learned to trust the preliminary and tentative art that patients,

clients, and workshop participants create, so too I have learned to trust my own preliminary and

tentative efforts to use my imagery to access that part of my faith tradition from which I have felt

disengaged.

There are understandings in this work that can be extended to bridge the practices of

clinical art therapy and spiritual engagement. Those interested in making spiritual practices

more inclusive and compelling to individuals whose modalities of expression are not entirely text

or language based can include image making as a form of worship. On the other hand, the

practitioners of clinical art psychotherapy can find ways to include the theories and spiritual

practices of faith traditions to ground their clinical work in deep and universal understandings of

human experience. More work needs to be done to understand the role of imagery as a bridge

between the unfortunately disconnected realms of the human experience identified reductively as

psychological and spiritual.

My explorations have stimulated the following incorporations of spiritual considerations

in my clinical thinking and practice:

1. Commitment to investigating ones own personal spiritual understandings supports

the bold and necessary openness that is the foundation for authentic clinical work.

2. Open mindedness/open heartedness to spiritual exploration on the part of the art

therapist invites expanded and broader engagement within the clinical dialogue.

Published by Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School, 2014

11

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, Vol. 2 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 5

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

12

As art therapist Pat Allen (2005) says, Art is a vehicle that allows us to transcend linear

time, to travel backward and forward into personal and transpersonal history, into possibilities

that werent realized and those that might be (pp. 1-2). I am convinced that art can be a

powerful vehicle for connecting the prayers or liturgical texts of religious traditions to an

individuals experience in a deeply personal and creative way. Also, I am convinced that the

practice of clinical art therapy can be deepened and broadened when the therapist opens her heart

and mind to the reverberations of her own spiritual questioning and to the spiritual questioning of

those with whom she works.

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/5

12

Linesch: Art Therapy and Hebrew Calligraphy

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

13

References

Adams, S. (2006). In my garment there is nothing but God. African Arts, 39, 26-35.

Allen, P. (2005). Art is a spiritual path. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Cameron, J. (1992). The artists way: A spiritual path to higher creativity. New York, NY:

Putnam Penguin.

Ellis, C., Adams, T., & Bochner, A. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum: Qualitative

Social Research 12, 1-18.

Farrelly-Hansen, M. (Ed.). (2001). Spiritual and art therapy: Living the connection. London,

England: Jessica Kingsley.

Horovitz, E. G. (2002). Spiritual art therapy: An alternative path. Springfield, IL: Charles C.

Thomas.

Kao, H., Zhu, L., Chao, A., Chen, H., Liu, I., & Zhang, M. (2014). Calligraphy and meditation

for stress reduction: An experimental comparison. Psychology Research and Behavior

Management, 7, 47-52.

Kushner, L. (1975). The book of letters. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights.

Linesch, D. (2013). Midrashic mirrors: Creating holiness with intimacy and imagery.

www.debralinesch.com .

Linesch, D., & Stettin, E. (2008). Panim el panim: Facing genesis visual midrash. Los Angeles,

CA: Marymount Institute Press.

McNiff, S. (2004). Art heals: How creativity cures the soul. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Milgrom, J. (1992). Handmade midrash. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society.

Moon, B. (1992). Essentials of art therapy training and practice. Springfield, IL: Charles C.

Thomas.

Published by Digital Commons at Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School, 2014

13

Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, Vol. 2 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 5

CALLIGRAPHY AND ART THERAPY

14

Rosove, J. (2002). High holiday machzor. Los Angeles, CA: Temple Israel of Hollywood.

Shahn, B. (1963). Love and joy about letters. New York, NY: Grossman.

Wuthnow, R. (2006). All in sync: How music and art are revitalizing American religion.

Berkeley, CA: University of Berkeley Press.

http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jcat/vol2/iss1/5

14

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Peter Levenda - Stairway To HeavenDokument324 SeitenPeter Levenda - Stairway To Heavenkenichi shukehiro100% (11)

- Continuum International Publishing Mysticism and Madness, The Religious Thought of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav (2009) PDFDokument321 SeitenContinuum International Publishing Mysticism and Madness, The Religious Thought of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav (2009) PDFBarbara Dworak-KaczorowskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Little Disillusionment Is A Good ThingDokument16 SeitenA Little Disillusionment Is A Good ThingCTSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cosmic Inner Smile - Smiling Heals The Body PDFDokument45 SeitenCosmic Inner Smile - Smiling Heals The Body PDFAlexandra Ioana Niculescu100% (1)

- Enochic Son of Man and The Pauline KyriosDokument22 SeitenEnochic Son of Man and The Pauline KyriosAíla Pinheiro de AndradeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magical Movements (Trulkhor) - Ancient Yogic Practices in The Bon Religion and Contemporary Medical PerspectivesDokument306 SeitenMagical Movements (Trulkhor) - Ancient Yogic Practices in The Bon Religion and Contemporary Medical Perspectivestsvoro100% (12)

- The Jewish Approach to Islam: Monotheism and Non-IdolatryDokument9 SeitenThe Jewish Approach to Islam: Monotheism and Non-Idolatryrazvan_nNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflections: Seymour Boorstein, M.D.Dokument16 SeitenReflections: Seymour Boorstein, M.D.Evgenia Flora LabrinidouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exhibition BookletDokument44 SeitenExhibition BookletR Flores Herrasti100% (1)

- Essays On The Practice of Magic in Antiquity (Review by Miller)Dokument3 SeitenEssays On The Practice of Magic in Antiquity (Review by Miller)TamehMNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of A LullabyDokument5 SeitenThe History of A LullabyroxanavamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 13 - Noahide Identity VDokument10 SeitenLesson 13 - Noahide Identity VMilan KokowiczNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Christian Passover Meal: Serving of Elijah'S CupDokument3 SeitenA Christian Passover Meal: Serving of Elijah'S CupAftene Ana MariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 31 Days of Prophetic DeclarationsDokument5 Seiten31 Days of Prophetic DeclarationsSJ Bataller100% (1)

- Shmuel Ettinger - The Hassidic Movement - Reality and IdealsDokument10 SeitenShmuel Ettinger - The Hassidic Movement - Reality and IdealsMarcusJastrow0% (1)

- Judgment in The House of God-Ebook PDFDokument80 SeitenJudgment in The House of God-Ebook PDFDan Oulaï100% (1)

- Truth Springs from the Earth: The Teachings of Rabbi Menahem Mendel of KotskVon EverandTruth Springs from the Earth: The Teachings of Rabbi Menahem Mendel of KotskNoch keine Bewertungen

- 42 JourneysDokument24 Seiten42 Journeyseliastemer6528Noch keine Bewertungen

- Prophets - Rayan Lobo, SJDokument7 SeitenProphets - Rayan Lobo, SJRayan Joel LoboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Jewish MysticismDokument7 SeitenIntroduction To Jewish Mysticismaryeh_amihayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Biblical Hebrew Thomas LambdinDokument189 SeitenIntroduction To Biblical Hebrew Thomas Lambdinmundinauta13017283% (6)

- A New Look at Atonement in Leviticus. The Meaning and Purpose of Kipper RevisitedDokument217 SeitenA New Look at Atonement in Leviticus. The Meaning and Purpose of Kipper RevisitedVolodya Lukin100% (3)

- The 1684 Sulzbach Edition of the ZoharDokument22 SeitenThe 1684 Sulzbach Edition of the ZoharJ Ricardo Tavares Jrpt IbhsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alan Brill - The Spiritual World of A Master of Aw, e Divine Vitality, Theosis, and Healing in The Degel Mahaneh EphraimDokument52 SeitenAlan Brill - The Spiritual World of A Master of Aw, e Divine Vitality, Theosis, and Healing in The Degel Mahaneh EphraimFrancesco VinciguerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Making of a Reform Jewish Cantor: Musical Authority, Cultural InvestmentVon EverandThe Making of a Reform Jewish Cantor: Musical Authority, Cultural InvestmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adam Afterman - Letter Permutation Techniques, Kavannah and Prayer in Jewish Mysticism PDFDokument27 SeitenAdam Afterman - Letter Permutation Techniques, Kavannah and Prayer in Jewish Mysticism PDFCristian Gris100% (1)

- Ebook Black Flags From PALESTINE - FullDokument150 SeitenEbook Black Flags From PALESTINE - FullBlackFlagsPalestine100% (1)

- Hearing Shofar: The Still Small Voice of The Ram's Horn - Vol 0Dokument9 SeitenHearing Shofar: The Still Small Voice of The Ram's Horn - Vol 0MichaelChusidNoch keine Bewertungen

- A New Physiognomy of Jewish Thi - Aubrey L. GlazerDokument225 SeitenA New Physiognomy of Jewish Thi - Aubrey L. GlazerDaniel Weiss100% (2)

- Yearnings of the Soul: Psychological Thought in Modern KabbalahVon EverandYearnings of the Soul: Psychological Thought in Modern KabbalahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ewing, Katherine Pratt - Arguing Sainthood - Modernity, Psychoanalysis, and Islam (1997)Dokument328 SeitenEwing, Katherine Pratt - Arguing Sainthood - Modernity, Psychoanalysis, and Islam (1997)Pedro Soares100% (1)

- GR 1103 EvansDokument14 SeitenGR 1103 EvansJoão Vitor Moreira MaiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dark Mirrors - Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology - Andrei A. OrlovDokument221 SeitenDark Mirrors - Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology - Andrei A. OrlovSam Gregory100% (1)

- Jewish Prayers to an Evolutionary God: Science In the SiddurVon EverandJewish Prayers to an Evolutionary God: Science In the SiddurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elliot Wolfson Abraham Ben Samuel Abulafia and The Prophetic KabbalahDokument12 SeitenElliot Wolfson Abraham Ben Samuel Abulafia and The Prophetic KabbalahAlexandre De Pomposo García-CohenNoch keine Bewertungen

- SDokument286 SeitenSKapwa Para HayahayNoch keine Bewertungen

- (15700593 - Aries) The Holy Cabala of ChangesDokument33 Seiten(15700593 - Aries) The Holy Cabala of ChangesJason BurrageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Through a Speculum That Shines: Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish MysticismVon EverandThrough a Speculum That Shines: Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish MysticismBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Sources and Studies in The Literature of Jewish Mysticism Edited Daniel AbramsDokument759 SeitenSources and Studies in The Literature of Jewish Mysticism Edited Daniel AbramsFulvidor Galté Oñate100% (1)

- 2006 - Golda Akhiezer - The Karaite Isaac Ben Abraham of Troki and His Polemics Against RabbanitesDokument32 Seiten2006 - Golda Akhiezer - The Karaite Isaac Ben Abraham of Troki and His Polemics Against Rabbanitesbuster301168Noch keine Bewertungen

- Culture in Minds and Societies - Foundations of Cultural Psychology-gPGDokument385 SeitenCulture in Minds and Societies - Foundations of Cultural Psychology-gPGDouglas Ramos Dantas100% (1)

- The Inscriptions of Kuntillet Ajrud Thro PDFDokument26 SeitenThe Inscriptions of Kuntillet Ajrud Thro PDFSamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Voice of Silence: A Rabbi’S Journey into a Trappist Monastery and Other ContemplationsVon EverandThe Voice of Silence: A Rabbi’S Journey into a Trappist Monastery and Other ContemplationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transcendental Judaism: Enlivening the Eternal Within to Uplift Ourselves and Our WorldVon EverandTranscendental Judaism: Enlivening the Eternal Within to Uplift Ourselves and Our WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transforming The Invisible: The Postmodernist Visual Artist As A Contemporary Mystic - A Review Christine HaberkornDokument25 SeitenTransforming The Invisible: The Postmodernist Visual Artist As A Contemporary Mystic - A Review Christine HaberkornJohn MichaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Female Crucifix: Images of St. Wilgefortis Since the Middle AgesVon EverandThe Female Crucifix: Images of St. Wilgefortis Since the Middle AgesBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (2)

- (SUNY Series in Judaica - Hermeneutics, Mysticism, and Religion) Moshe Idel - The Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia (1988, State University of New York Press)Dokument262 Seiten(SUNY Series in Judaica - Hermeneutics, Mysticism, and Religion) Moshe Idel - The Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia (1988, State University of New York Press)funkmeister2000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Existential Therapy Emmy Van DeurzenDokument37 SeitenExistential Therapy Emmy Van DeurzenNucha NaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Borges and The Kabbalah Pre-Texts To A TDokument8 SeitenBorges and The Kabbalah Pre-Texts To A TMariaLuisaGirondoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eitan P. Fishbane - A Chariot For The Shekhinah Identity and The Ideal Life in Sixteenth-Century KabbalahDokument34 SeitenEitan P. Fishbane - A Chariot For The Shekhinah Identity and The Ideal Life in Sixteenth-Century KabbalahMarcusJastrow100% (1)

- 006 El Adon Al Kol HamaasimDokument4 Seiten006 El Adon Al Kol HamaasimYiṣḥâq Bên AvrôhômNoch keine Bewertungen

- 24 3gillerDokument26 Seiten24 3gillerAllen HansenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revitalizing Islamic Art TherapyDokument21 SeitenRevitalizing Islamic Art TherapyNadir KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leshem Yichud before watching moviesDokument1 SeiteLeshem Yichud before watching moviesDavid Saportas LièvanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knotter Kabbalah-TheArtofJewishMysticism2018 PDFDokument33 SeitenKnotter Kabbalah-TheArtofJewishMysticism2018 PDFFrancesco67Noch keine Bewertungen

- No Longer Lonely: A Gay Former Priest Journeys from His Secret to Freedom.Von EverandNo Longer Lonely: A Gay Former Priest Journeys from His Secret to Freedom.Noch keine Bewertungen

- New Ancient Words and New Ancient Worlds - Review of Daniel Matt's ZoharDokument32 SeitenNew Ancient Words and New Ancient Worlds - Review of Daniel Matt's ZoharjoelheckerNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Remembrance of His Wonders: Nature and the Supernatural in Medieval AshkenazVon EverandA Remembrance of His Wonders: Nature and the Supernatural in Medieval AshkenazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living Karma: The Religious Practices of Ouyi ZhixuVon EverandLiving Karma: The Religious Practices of Ouyi ZhixuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Religiao e SociedadeDokument26 SeitenReligiao e SociedadetodogomiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gerardus Van Der Leeuw biography and phenomenology of religionDokument4 SeitenGerardus Van Der Leeuw biography and phenomenology of religionToshi ToshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Religious CultureDokument18 SeitenJournal of Religious CultureSoojungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Existential Psychology in ChinaDokument5 SeitenExistential Psychology in ChinasoucapazNoch keine Bewertungen

- RICE WEBER, Vicki - Ph.D. - 2016Dokument363 SeitenRICE WEBER, Vicki - Ph.D. - 2016Gloria Rinchen ChödrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- William W. Quinn, Jr. - Mircea Eliade and The Sacred Tradition, A Personal AccountDokument8 SeitenWilliam W. Quinn, Jr. - Mircea Eliade and The Sacred Tradition, A Personal AccountKenneth AndersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Looking Two Ways by 25thDokument25 SeitenLooking Two Ways by 25thsooyeun_youNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review On The BookDokument6 SeitenA Review On The BookAjay SahotajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poetry Therapy ThesisDokument20 SeitenPoetry Therapy Thesisapi-481780857Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Theory Isna-1Dokument10 SeitenLiterary Theory Isna-1Nur Al-AsimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Images of Sexualities Language and Embodiment in Art TherapyDokument10 SeitenImages of Sexualities Language and Embodiment in Art Therapy乙嘉Noch keine Bewertungen

- Knibe Why Participation Matters To Understand PDFDokument16 SeitenKnibe Why Participation Matters To Understand PDFcristian rNoch keine Bewertungen

- MA APT RoehamptonDokument20 SeitenMA APT RoehamptonNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teoria Del Campo Baranger PDFDokument15 SeitenTeoria Del Campo Baranger PDFNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.14 Creating - Your - Unique - Selling - Point PDFDokument1 Seite1.14 Creating - Your - Unique - Selling - Point PDFNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- To Do: You Completed 5 Steps! Get Your Free Digital UpgradeDokument3 SeitenTo Do: You Completed 5 Steps! Get Your Free Digital UpgradeNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of What Who They AreDokument1 SeiteList of What Who They AreAtaa ElhefnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- To Do: You Completed 5 Steps! Get Your Free Digital UpgradeDokument3 SeitenTo Do: You Completed 5 Steps! Get Your Free Digital UpgradeNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Succeed At: Writing Applications: Research Into An OrganisationDokument1 SeiteHow To Succeed At: Writing Applications: Research Into An OrganisationStü RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Making A StartDokument2 SeitenMaking A StartNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Statement For JobsDokument3 SeitenPersonal Statement For JobsNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Getting To Know YouDokument9 SeitenGetting To Know YouNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Researching Universities or CollegesDokument3 SeitenResearching Universities or CollegesNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysing Job AdvertsDokument2 SeitenAnalysing Job AdvertsNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminarios de Kohut Cap 2Dokument8 SeitenSeminarios de Kohut Cap 2Nicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teoria Del Campo Baranger PDFDokument15 SeitenTeoria Del Campo Baranger PDFNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysing Course DescriptionsDokument2 SeitenAnalysing Course DescriptionsNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davanloo GodDokument10 SeitenDavanloo GodNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cap 5 de Los Seminarios de KohutDokument9 SeitenCap 5 de Los Seminarios de KohutNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davanloo GodDokument10 SeitenDavanloo GodNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minfulness y PobrezaDokument19 SeitenMinfulness y PobrezaNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrating Structure and Function Looking at The Brain in The Context of Internal Psychological ProcessesDokument3 SeitenIntegrating Structure and Function Looking at The Brain in The Context of Internal Psychological ProcessesdrguillermomedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Vital ProfessionDokument29 SeitenOur Vital ProfessionNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capacidad Reflexiva en EsquizofreniaDokument11 SeitenCapacidad Reflexiva en EsquizofreniaNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minfulness y PobrezaDokument19 SeitenMinfulness y PobrezaNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art Therapy Domestic Violence Group in MexicoDokument10 SeitenArt Therapy Domestic Violence Group in MexicoNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magic TreeDokument3 SeitenMagic TreeNicolas ObiglioNoch keine Bewertungen

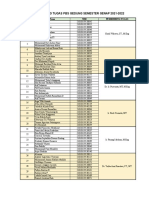

- 6.0 Senarai Keahlian Bsmm-DisahkanDokument3 Seiten6.0 Senarai Keahlian Bsmm-DisahkanNOOR HIDAYAH BINTI JAMALUDIN MoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- التسامح والتعايش بين المسلمين وأهل الذمة ببلاد الأندلس إلى نهاية عصر المرابطين92-520 هـ - 711-1126مDokument24 Seitenالتسامح والتعايش بين المسلمين وأهل الذمة ببلاد الأندلس إلى نهاية عصر المرابطين92-520 هـ - 711-1126مmunir salhenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Midwives' Courageous Choice to Obey GodDokument3 SeitenThe Midwives' Courageous Choice to Obey GodRENE CATALAN LACABANoch keine Bewertungen

- Uva-Dare (Digital Academic Repository) : A Sanguine Bunch . Regional Identification in Habsburg Bukovina, 1774-1919Dokument28 SeitenUva-Dare (Digital Academic Repository) : A Sanguine Bunch . Regional Identification in Habsburg Bukovina, 1774-1919Petru DeaconuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life and Ministry 1Dokument3 SeitenLife and Ministry 1api-526734134Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard WayDokument10 SeitenThe Hard WayElaine DGNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Miracle of Life: Blessings For The Body, For Study (The Mind), and For The SoulDokument1 SeiteThe Miracle of Life: Blessings For The Body, For Study (The Mind), and For The SoulboazoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Last WishDokument4 SeitenLast WishBala cheggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shekinah GloryDokument11 SeitenShekinah GloryMULENGA BWALYANoch keine Bewertungen

- Pembimbing Tugas PBS Gedung - Genap 2021-2022Dokument2 SeitenPembimbing Tugas PBS Gedung - Genap 2021-2022YAMudhofarNoch keine Bewertungen

- God Is Free To Act According To His Redemptive Purposes.: Remember That Romans 9:15 Is A Quote From Exodus 33:19Dokument4 SeitenGod Is Free To Act According To His Redemptive Purposes.: Remember That Romans 9:15 Is A Quote From Exodus 33:19Maria Garcia Pimentel Vanguardia IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Romeo and Juliet Movie DialoguesDokument3 SeitenRomeo and Juliet Movie DialoguesNathi JuayekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Margin of Error-LibreDokument6 SeitenMargin of Error-LibreMitran MitrevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tisha B'Av Excerpt-from-Kinot-Mesorat-HaRav-2020 - 02 - 02Dokument57 SeitenTisha B'Av Excerpt-from-Kinot-Mesorat-HaRav-2020 - 02 - 02shasdafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exegetical Analysis of Romans 4Dokument9 SeitenExegetical Analysis of Romans 4mung_khatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Josephus on Prodigies Before Destruction of Jerusalem TempleDokument3 SeitenJosephus on Prodigies Before Destruction of Jerusalem TempleRubenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digitalization Project of Montefiore Censuses 19th CenturyDokument65 SeitenDigitalization Project of Montefiore Censuses 19th CenturyisragenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tendaystenways Final1Dokument62 SeitenTendaystenways Final1Alber SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen