Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

(OA) Anxiety May Enhance Pain During Dental Treatment PDF

Hochgeladen von

MuabhiOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

(OA) Anxiety May Enhance Pain During Dental Treatment PDF

Hochgeladen von

MuabhiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

51

Bull Tokyo Dent Coll (2005) 46 (3): 5158

Original Article

Anxiety May Enhance Pain during Dental Treatment

Keiko Okawa, Tatsuya Ichinohe and Yuzuru Kaneko

Department of Dental Anesthesiology, Tokyo Dental College,

1-2-2 Masago, Mihama-ku, Chiba 261-8502, Japan

Received 25 November, 2005/Accepted for Publication 21 December, 2005

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to clarify the effects of anxiety about dental treatment

on pain during treatment. Subjects consisted of 57 consenting sixth-grade students at

Tokyo Dental College (male: 32, female: 25), all of whom participated in this study during

their clinical training program. They knew how third molars were extracted and all had

experience of assisting in tooth extraction. Prior to the study, trait anxiety in the subjects

was evaluated according to the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Japanese version).

The students were asked to read one of two scenarios describing a scene in which a third

molar was extracted while imagining themselves to be the patient. Scene 1 is set in an

environment where the patient feels safe and comfortable, and the Scene 2 is set in an

environment where the patient feels strong anxiety. The subjects were asked to imagine

the anxiety and pain in that scenario and evaluate that pain according to a visual analogue scale (VAS). Two scenarios were randomly shown to the subjects in a crossover

manner. No significant correlation between trait anxiety and preoperative anxiety was

observed. There was no difference in level of preoperative anxiety for Scene 1 and Scene

2 between the high- and low-trait anxiety groups. This suggests that there was no relationship between sensitivity to anxiety as a characteristic of the subject and amplitude of

anxiety immediately prior to treatment. Scene 2 elicited significantly higher anxiety

before injection of regional anesthesia, significantly higher pain during insertion of the

needle, and significantly higher pain during extraction of the tooth than Scene 1. This

difference suggests that patients feel stronger pain if anxiety in the treatment environment is high and that it is, therefore, important to reduce anxiety during treatment to

reduce pain.

Key words:

Anxiety Pain Dental treatment

Introduction

as fainting or hyperventilation syndrome.

However, patients sometimes die of acute

heart failure or cerebrovascular accident1,3,5,9,10).

In general, anxiety and fear are said to

enhance pain. According to one report discussing the relationship between amplitude

of anxiety as a characteristic of a patient (trait

anxiety) or amplitude of anxiety when secur-

For most dental patients, dental treatment

is painful and scary. Anxiety and tension

about dental treatment may cause systemic

complications. More than half of systemic

complications develop during local anesthesia. Most complications are not critical, such

51

52

Okawa K et al.

Table 1 Script (Scene 1)

The following is a text of a hypothetical dental care situation. Read the text and imagine that you are the patient.

You will be asked about your condition several times during the process. Use the tool provided to record your

condition each time.

Scene 1

Your third molar is to be extracted today. The dentist in charge is your regular dentist. The dentist is well

appreciated by his patients, and is known to be skillful at extracting teeth. The dental hygienist is caring, and the

dental clinic has a very warm atmosphere.

You are taken to the dentist chair. After a while, your regular dentist comes in with a smile on his face.

Hello. How are you today?

You say, Fine, nodding.

Are you a little nervous? Its going to be fine. Let me know if you start feeling ill.

The dentist sees that you seem different than usual.

Record 1: Record the degree of your anxiety regarding the tooth extraction.

We will numb the area. Lets bring the chair down.

You will feel a little sting. Breathe slowly through your nose. You can raise your hand if you start feeling ill.

Dont hesitate to let me know.

Record 2: Imagine and record the pain when the needle with the local anesthetic is inserted.

Are you feeling all right? Shall we start?

Does it hurt?

The anesthetic appears to be working.

Let me know if it hurts or you start feeling ill.

First, I will break the tooth.

You hear the sound of a turbine and have a painful expression on your face.

Are you all right? Does it hurt?

The dentist quickly notices the change in your facial expression.

Im all right.

The turbine is turned off, and breaking of the tooth is finished.

Its almost over. You may feel a slight discomfort. Hang in there.

. . . A creaking sound . . . The tooth appears to be coming out.

Record 3: You felt a slight pain at this time. Imagine and record the degree of the pain.

ing a vein (state anxiety) and subjective

strength of pain4), subjects with higher trait

anxiety showed a stronger state anxiety and

realized stronger pain when a vein was punctured and a catheter inserted than a subject

with lower trait anxiety. This suggests that

patients with a stronger anxiety trait tend to

experience stronger anxiety during dental

treatment than patients with a weaker anxiety

trait and that they are likely to feel more pain.

Another study reported that patients with

stronger state anxiety experienced stronger

pain when having veins punctured7). However, these studies do not directly discuss

dental treatment. Therefore, it has yet to be

determined whether anxiety about dental

treatment affects pain during such treatment.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the

effects of anxiety about dental treatment on

pain during treatment. Subjects were asked to

read two scenarios describing a scene in

which a third molar was extracted. The relationship between anxiety and pain was discussed based on the VAS (Visual Analogue

Scale) values of anxiety and pain obtained

while the subjects were reading the scenarios.

Subjects and Method

Subjects consisted of 57 consenting sixthgrade students at Tokyo Dental College

(male: 32, female: 25). The specific content of

the study was not explained to them to prevent preoccupation from affecting the results.

All subjects participated in this study during

Anxiety Enhances Pain in Dental Patients

53

Table 1 Script (Scene 2)

The following is the text of a hypothetical dental care situation. Read the text and imagine that you are the patient.

You will be asked about your condition several times during the process. Use the tool provided to record your

condition each time.

Scene 2

Your third molar is to be extracted today. Your regular dentist referred you to an oral surgeon. An unfriendly dental

hygienist calls you. You enter the clinic and see a lot of chairs and doctors. This unfamiliar sight takes you by

surprise.

You see a young dentist in the clinic. The dentist asks you about your medical condition.

Is this the dentist who is going to pull my tooth out?

The dentist examines the inside of your mouth. He seems inexperienced . . .

I wonder if I can trust him. . .

After awhile an experienced dentist comes in.

Hello. My name is ****. I will be working with Dr. **** today.

You feel relieved, but this setting is not familiar to you . . .

Record 1: Record the degree of your anxiety regarding the tooth extraction.

I am going to numb the area. Lets bring the chair down.

You are not quite ready for it... But the procedure is about to begin.

OK, Dr. ****, would you numb the area?

My god! Is he going to do it?

The needle comes close to your face, and then it goes inside your mouth. . .

No, not there.

Oh, Im sorry.

Its going to sting a little. Breathe slowly through your nose.

Record 2: Imagine and record the pain when needle with the local anesthetic is inserted.

The chair is brought down again. It appears that the procedure is about to begin.

OK, here we go.

I wonder if the anesthetic is working. . . The dentist doesnt ask at all.

What if I feel the pain? I wonder if I am supposed to put up with it a little . . .

The young dentist appears to be the one who will extract the tooth. Just as you thought, he doesnt seem to be

experienced with the procedure. He doesnt work smoothly, and the experienced dentist sometimes takes over.

You hear the sound of the turbine . . . You unconsciously develop a painful expression on your face. However, the

dentist doesnt stop. He is only looking at the inside of your mouth. You constantly hear the instructions by the

experienced dentist.

It feels as if its taking too long. You are tired from keeping your mouth open.

A creaking sound . . . Your chin feels more weight placed on it.

Hold on a little longer. You may feel a discomfort, but the tooth is almost out . . .

Record 3: You felt a slight pain at this time. Imagine and record the pain.

their clinical training program. They knew

how a third molar was extracted and all had

experience of assisting in tooth extraction.

Before the study, the trait anxiety of the

subjects was evaluated according to the StateTrait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Japanese version), which is a self-administered psychological test with no time restriction. The subjects

were then asked to read one of two scenarios

describing a scene in which a third molar was

extracted while imagining themselves to be

the patient. They were asked to imagine the

anxiety and pain that scenario would elicit

and evaluate that pain according to the visual

analogue scale (VAS). They were next asked

to read another scenario after an at least twoday interval and repeat the same evaluation in

the same manner.

These scenarios consisted of a scene describing the extraction of a third molar. One is set

in an environment where the patient feels

safe and comfortable, and the other is set in

an environment where the patient feels

strong anxiety (Table 1). The timing of the

54

Okawa K et al.

Fig. 1 Relationship between STAI values and preoperative anxiety for total subjects

Fig. 2 Relationship between STAI values and preoperative anxiety for female subjects

evaluations were: (1) anxiety before injection

of local anesthesia, (2) pain during insertion

of a needle, and (3) pain during extraction of

the tooth. In VAS evaluation, the left end

of the scale (0 mm) indicates no anxiety or

pain, and the right end (100 mm) indicates

strongest anxiety or pain imaginable. Subjects were asked to evaluate the degree of

their own anxiety and pain on the scale.

The data were expressed as an average

valuethe standard deviation. The Spearman

rank correlation and Wilcoxon signed-ranksum test were used for statistical analyses. A

significance level of p0.05 was considered to

be significant.

Results

1. Relationship between STAI values and

preoperative anxiety (VAS)

There was no significant correlation between STAI values and preoperative anxiety

(VAS) for any subject (Scene 1: rs0.18,

Scene 2: rs0.10; Fig. 1); in female subjects

(Scene 1: rs0.20, Scene 2: rs0.10; Fig. 2);

and in male subjects (Scene 1: rs0.18, Scene

2: rs0.11; Fig. 3).

Values of STAI were divided into two

groups including less than average (2446,

38.86.2) and more than average (4774,

54.56.8) and the preoperative anxiety levels

of Scene 1 and Scene 2 were compared.

There was no significant difference in Scene 1

Anxiety Enhances Pain in Dental Patients

55

Fig. 3 Relationship between STAI values and preoperative anxiety for male subjects

Fig. 4 Relationship between STAI values and

preoperative anxiety

Fig. 5 Comparison between Scene 1 and Scene 2

for total subjects

(less than average: 39.024.3, more than

average : 41.925.4), or in Scene 2 (less than:

63.121.0, more than average : 64.523.7;

Fig. 4).

anesthesia was 40.424.6 and 63.822.2 for

Scene 1 and Scene 2, respectively. The pain

during insertion of the needle was 46.930.2

and 76.521.3 for Scene 1 and Scene 2,

respectively. The pain during extraction of

the tooth was 51.723.2 and 69.521.9 for

Scene 1 and Scene 2, respectively. In all cases,

Scene 2 showed significantly higher values

than Scene 1 (Fig. 5).

2. Comparison between Scene 1 and

Scene 2

When comparing Scene 1 and Scene 2, the

anxiety of subjects before injection of local

56

Okawa K et al.

Fig. 6 Comparison between Scene 1 and Scene 2

for female subjects

Fig. 7 Comparison between Scene 1 and Scene 2

for male subjects

In females, anxiety before injection of

regional anesthesia was 39.024.3 and

63.121.6 for Scene 1 and Scene 2, respectively. The pain during insertion of the needle

was 49.631.7 and 76.122.0 for Scene 1

and Scene 2, respectively. The pain during

extraction of the tooth was 53.425.8 and

71.522.6 for Scene 1 and Scene 2, respectively. In all cases, Scene 2 showed significantly higher values than Scene 1 (Fig. 6).

In males, the anxiety before injection of

regional anesthesia was 37.023.8 and

58.422.7 for Scene 1 and Scene 2, respectively. The pain during insertion of the needle

was 38.527.2 and 71.321.9 for Scene 1

and Scene 2, respectively. The pain during

extraction of the tooth was 45.721.6 and

64.221.2 for Scene 1 and Scene 2, respectively. In all cases, Scene 2 showed significantly higher values than Scene 1 (Fig. 7).

In all conditions, females showed higher

values than males. However, there was no statistically significant difference.

Discussion

No significant correlation was found between trait anxiety and preoperative anxiety

in this study. Furthermore, there was no difference in the preoperative anxiety of Scene 1

and Scene 2 between the high- and low-trait

anxiety groups. This suggests that there was

no relationship between sensitivity to anxiety

as a characteristic of a patient and amplitude

of anxiety immediately before treatment.

Scene 2 elicited significantly higher anxiety

before injection of the regional anesthesia,

significantly higher pain during insertion of

the needle, and significantly higher pain during extraction of the tooth than Scene 1. This

suggests that subjects feel stronger pain if

anxiety in therapeutic environment is high.

1. Subjects

The subjects consisted of sixth-grader dental

students. It was assumed that they well understood the flow of tooth extraction, including

local anesthesia, as they all had experience of

clinical training. In addition, they all had

Anxiety Enhances Pain in Dental Patients

training in infiltration anesthesia and infraalveolar nerve block. Therefore, it was supposed that they would be able to imagine the

pain that would occur during the insertion of

a needle based on their experience.

Less than half of the students (male: 15/32,

female: 11/25), however, had experienced a

third molar extraction. Therefore, it was difficult for most of the subjects to imagine the

pain and discomfort of tooth extraction based

on personal experiences. However, in this

study, lack of personal experience of tooth

extraction had only a small effect on the difference between Scene 1 and Scene 2, as each

subject evaluated both scenarios in a crossover

manner.

Since all the subjects in this study were

dental students, this specialized experimental

condition may have affected the results.

Further study should use subjects who are

not specialists in medicine or dentistry.

2. Method

In this study, anxiety and pain were evaluated according to VAS, using two scenarios of

third molar extraction, including one with an

environment where the patient feels strong

anxiety and one with an environment where

the patient feels safe and comfortable.

The best way to evaluate anxiety and pain

during dental treatment is to evaluate patients

in the actual environment of tooth extraction.

However, it is ethically unacceptable to artificially create an environment where a patient

feels strong anxiety. Therefore, in this study,

we used a method where the subjects were

made to imagine anxiety and pain by using

scenarios.

There are several methods of evaluating

anxiety. Among them, STAI is the standard

method8). STAI can evaluate both trait anxiety, which indicates strength of anxiety based

on the character of a subject, and state anxiety, which indicates strength of anxiety within

a particular environment. However, it takes

1520 minutes to fill in the STAI questionnaire. Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate state

anxiety by STAI while reading a scenario, as

was done in this study. Therefore, VAS was

57

used to evaluate state anxiety in this study. It

has been reported that there is a good correlation between STAI and VAS when used to

evaluate state anxiety9).

3. Relationship between trait anxiety and

state anxiety of subjects before extraction of tooth

This study found no relationship between

trait anxiety in the subjects and state anxiety

before extraction of a tooth. In other words, a

person who hardly feels anxiety under normal

circumstances may feel strong anxiety if the

environment for treatment is bad and vice

versa.

According to one report discussing the

relationship between trait anxiety and state

anxiety when securing a subjects vein6), subjects with strong trait anxiety showed a greater

increase in state anxiety when puncturing a

vein and inserting a catheter than subjects

who did not have strong trait anxiety. However, in this study, there was no difference in

anxiety levels on entering the examination

room between the subjects.

Therefore, it is necessary to create a clinical

environment that does not promote patient

anxiety.

4. Relationship between state anxiety

before extraction of tooth and pain

during insertion of needle and extraction of tooth

The results of this study suggest that a

patient feels stronger pain if the state anxiety

is strong in the therapeutic environment, and

anxiety enhances pain irrespective of personal sensitivity to anxiety. Therefore, the

same as previous reports on the relationship

between state anxiety and pain when securing

a vein4,7), this study found that there was a

relationship between state anxiety and pain in

dental treatment. In a recent study2), expectation of decreased pain reduced subjective

experience of pain in healthy volunteers. Our

results agree with that finding. We believe,

therefore, that we may extrapolate our current results to generalized subjects who are

not engaged in medical fields.

58

Okawa K et al.

In this study, there was no difference in

degree of anxiety before extraction of a tooth

between female and male subjects. The

same result was reported in a paper on preoperative state anxiety in patients with jaw

deformities10). Furthermore, it was supposed

that there was no difference in the effect

of state anxiety on pain between male and

female subjects, as there was no difference in

state anxiety and degree of pain during insertion of a needle and extraction of a tooth

between male and female subjects. Therefore, these results suggest that it is important

to establish a therapeutic environment that

gives minimum anxiety to patients in order to

reduce pain during treatment.

In conclusion, in this study, we discussed

the effects of level of anxiety about dental

treatment on pain during treatment. We

found no relationship between trait anxiety in

a subject and state anxiety before extraction

of a tooth. In contrast, patients felt strong

pain if state anxiety in the treatment environment was strong. As shown above, it is important to reduce anxiety during treatment to

reduce pain during treatment.

3)

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

9)

10)

References

1) Agata H, Ichinohe T, Nagatsuka C, Fukuda K,

Mamiya H, Abe K, Sugiyama A, Kaneko Y

(1997) Medical emergencies treated in Tokyo

Dental College Chiba Hospital. J Jpn Dent Soc

Anesthesiol 25:8288.

2) Koyama T, McHaffie JG, Laurienti PJ, Coghill

RC (2005) The subjective experience of pain:

Where expectations become reality. PNAS

102:1295012955.

Kubo K, Agata H, Sakurai S, Ichinohe T,

Kaneko Y (2005) Medical emergencies treated

in Tokyo Dental College Chiba Hospital. J Jpn

Dent Soc Anesthesiol 33:6873.

Kudo M, Ooke H, Kawai T, Kato M, Kokubu M,

Shinya M (2000) The relationship between

trait anxiety and pain sensation Anxiety and

pain levels at puncture and cannulation in

high anxiety state volunteers. J Jpn Dent Soc

Anesthesiol 28:587593.

Matsuura H (1986) Accidental symptoms

related to dental anesthesia. J Jpn Dent Assoc

39:6574.

Moerman N, van Dam F, Muller M, Oosting H

(1996) The Amsterdam preoperative anxiety

and information scale (APAIS). Anesth Analg

82:445451.

Sakamoto E, Shiiba S, Imamura Y, Iwamoto S,

Kawahara H, Nakanishi O (2002) The study of

the relationship between anxiety and pain.

Clinic All-round 51:27032706.

Sakurai M, Ichinohe T, Nomura K, Koukita Y,

Kaneko Y (2001) A psychological evaluation of

preoperative acute anxiety in patients with jaw

deformity. J Jpn Dent Soc Anesth 29:229232.

Shinya N (1992) Accidental symptoms related

to dental anesthesia. J Jpn Dent Assoc 45:63

72.

Someya G, Shinya N (1999) Accidental symptoms related to dental anesthesia. J Jpn Dent

Soc Anesthesiol 27:365373.

Reprint requests to:

Dr. Keiko Okawa

Department of Dental Anesthesiology,

Tokyo Dental College

1-2-2 Masago, Mihama-ku,

Chiba 261-8502, Japan

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- (CR) Early Childhood Caries A Case Report of An Extensive Rehabilitation (2018)Dokument3 Seiten(CR) Early Childhood Caries A Case Report of An Extensive Rehabilitation (2018)MuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- (A) Dental Health Psychology Service For Adults With Dental AnxietyDokument8 Seiten(A) Dental Health Psychology Service For Adults With Dental AnxietyMuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- (J) Psychological and Physiological of A Head Down Titled ConditionDokument39 Seiten(J) Psychological and Physiological of A Head Down Titled ConditionMuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Normal RadiographicDokument45 SeitenNormal RadiographicMuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MUN Rules of ProcedureDokument13 SeitenMUN Rules of ProcedureMuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Example of Position PaperDokument1 SeiteExample of Position PaperHadley AuliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Assembly Study GuideDokument1 SeiteGeneral Assembly Study GuideMuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metode Pengisian Saluran AkarDokument1 SeiteMetode Pengisian Saluran AkarMuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- (PPT) Oral Health and Down SyndromeDokument31 Seiten(PPT) Oral Health and Down SyndromeMuabhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Theories On Factors Affecting MotivationDokument24 SeitenTheories On Factors Affecting Motivationmyra katrina mansan100% (5)

- 3f PDFDokument4 Seiten3f PDFYidne GeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PQC-POL002 Qualification Guide For CertOH and iCertOH v1.0Dokument25 SeitenPQC-POL002 Qualification Guide For CertOH and iCertOH v1.0Nathan MwewaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Study - MidazolamDokument8 SeitenDrug Study - MidazolamKian HerreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electronic Care and Needs Scale eCANSDokument2 SeitenElectronic Care and Needs Scale eCANSamanda wuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health EducationDokument8 SeitenHealth EducationJamie Rose FontanillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antimicrobial ResistanceDokument46 SeitenAntimicrobial ResistanceEmil CotenescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeehp 12 06Dokument4 SeitenJeehp 12 06Sohini KhushiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20100829035427388Dokument374 Seiten20100829035427388Reeza Amir Hamzah100% (1)

- Task Exposure AnalysisDokument24 SeitenTask Exposure AnalysisDaren Bundalian RosalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- HS-Rev.00 Hazardous Substance - Chemical Assessment SheetDokument2 SeitenHS-Rev.00 Hazardous Substance - Chemical Assessment Sheetlim kang haiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knee Pain and The Internal Arts: Correct Alignment (Standing)Dokument7 SeitenKnee Pain and The Internal Arts: Correct Alignment (Standing)Gabriel PedrozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avocado Production in The PhilippinesDokument20 SeitenAvocado Production in The Philippinescutieaiko100% (1)

- Feeding Norms Poultry76Dokument14 SeitenFeeding Norms Poultry76Ramesh BeniwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychology of ProcrastinationDokument7 SeitenPsychology of ProcrastinationPauline Wallin100% (2)

- My Evaluation in LnuDokument4 SeitenMy Evaluation in LnuReyjan ApolonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding My Benefits: Pre - Auth@Dokument2 SeitenUnderstanding My Benefits: Pre - Auth@Jonelle Morris-DawkinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Litigation Explosion - Walter K. OlsonDokument424 SeitenThe Litigation Explosion - Walter K. OlsonNaturaleza Salvaje100% (1)

- Resume 3Dokument2 SeitenResume 3api-458753728Noch keine Bewertungen

- Doh2011 2013isspDokument191 SeitenDoh2011 2013isspJay Pee CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

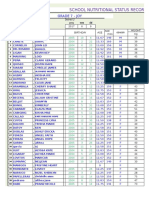

- School Nutritional Status Record: Grade 7 - JoyDokument4 SeitenSchool Nutritional Status Record: Grade 7 - JoySidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effectiveness of Maitland vs. Mulligan Mobilization Techniques in (Ingles)Dokument4 SeitenEffectiveness of Maitland vs. Mulligan Mobilization Techniques in (Ingles)mauricio castroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Promoting Smart Farming, Eco-Friendly and Innovative Technologies For Sustainable Coconut DevelopmentDokument4 SeitenPromoting Smart Farming, Eco-Friendly and Innovative Technologies For Sustainable Coconut DevelopmentMuhammad Maulana Sidik0% (1)

- DR John Chew (SPMPS President) PresentationDokument50 SeitenDR John Chew (SPMPS President) PresentationdrtshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baby Led-WeaningDokument7 SeitenBaby Led-WeaningsophieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bicon Product Catalog 2013Dokument12 SeitenBicon Product Catalog 2013Bicon Implant InaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organ SystemsDokument2 SeitenOrgan SystemsArnel LaspinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vstep Tests B1 B2 C1 Full KeyDokument162 SeitenVstep Tests B1 B2 C1 Full KeyLe Hoang LinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar PustakaDokument2 SeitenDaftar PustakaameliaaarrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climbing Training Log - TemplateDokument19 SeitenClimbing Training Log - TemplateKam Iqar ZeNoch keine Bewertungen