Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

English 104

Hochgeladen von

Tibor BoruzsCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

English 104

Hochgeladen von

Tibor BoruzsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HOW MANY MILLIONS?

The Statistics of English Today

DAVID

CRYSTAL

In

the first, that is, from 1558 to 1603

the number

reign of of

Queen

Elizabeth

- the

English

speakersin the world is thought to have been

between 5 and 7 million. At the

beginning of the reign of the second

Queen Elizabeth in 1952, the figure

had increased almost fiftyfold. In

1962, Randolph Quirk estimated in

The Use of English that 250 millions

had English as a mother tongue, with

a further 100 million using it as a

second or foreign language.

Fifteen years later, and we find

Joshua Fishman and his colleagues,

in The Spread of English, citing 300

million for the mother tongue category. A further 300 million is said to

use it as an additional language.

These figures are the ones which are

repeatedly quoted throughout the

statistically-conscious 1970s. They

are adopted by Bailey and Gorlach as

recently as 1982, in their English as a

World Language. But they are now

very much out of date. In 1984,

several sources collected by the

Centre for Information on Language

Teaching in London indicated that

the figure would have to be raised by

100million. One analysis, quite often

"""",.-",<~.",--<.,r--""''''''''''~'''',~~.;'~';'''~_''''N.""._""",.""

DAVID CRYSTAL read English at University

College, London, and was for a time

lecturer in linguistics at the University

College of North Wales, before moving in

1965 to the University of Reading, where

he is currently Professor of Linguistic

Science. He has been a visiting lecturer in

many parts of Europe, the United States,

Canada, Australia, and South America. His

publications include Linguistics, The

English Tone of Voice, Clinical Linguistics,

Who Cares About English Usage?, and

Child Language, Learning and Linguistics.

He also broadcasts frequently with the BBC

on language in general and English in

particular. His wife Hilary is a speech

therapist, and currently collaborates with

him on research into language handicap

under the sponsorship of the British

Medical Research Council. They currently

live in Holyhead, Wales.

referred to, gives mother-tongue use

as 300 million, second language use

also as 300 million, and foreign

language use as 100 million. This was

the total used by Quirk in his address

to the British Council's anniversary

conference on 'Progress in English

Studies' in September 1984. So there

we are. 700 millions.

But actually, there we aren't. For

in Erik Gunnemark and Donald

Kenrick's geolinguistic handbook,

What

Language

Do

They Speak? ,

published privately in 1983, we are

given a detailed list of English

speaker totals. The home language

total is unremarkable - they cite 'over

300 million'. It is the figure for

English as an 'official language' which

grabs the eye: over 1,400 million!

Allowing a further 100 million or so

for speakers as a foreign language, we

ENGLISH TODAY No. 1 - JANUARY 1985

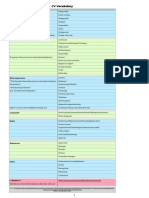

COUNTRY

Anguilla

Antigua-Barbuda

Australia

Bahamas & _5\"'~L.

Barbados

Belize

Bermuda

Botswana

Brunei

Cameroon

Canada

Cook Tslflnds

Dominica

Ethiopia

Fiji

Ghana

Gibraltar

Great Britain

Grenada

Guyana

Hong Kong

India

Irish Republic

Jamaica

Kenya

Kiribati

Lesotho

Liberia

Malaysia (East)

Malawi

Malta

Mauritius

Montserrat

Namibia

Nauru

New Zealan~.

Pakistan

~"eI:A..

l?apu3;New Guinea

Philippines

Senegambia

Seychelles

Sierra Leone

Singapore

Solo~ol1 I$lands

South Afri~a

St"Kitts & Nevis

St Lucia .

St Vincent

Swaziland

Tanzania

Tonga

Trinidad & Tobago

Tuvalu

Uganda

United States

USA territories, Pacific

Vanuatu

Western Samoa

Zambia

Zimbabwe

various British territories

TOTALS

FIRST LAN~UAvE

SPEAKERS

10,000100,000

14,000,000

250,000

250,000+

100,000+

50,000+

10,000

100,000

15,000,000250,0.00

259,.000+

150,00.0+

50,0.00+

1,000,000200,000+

8,OQO,000+

24,.0.0.0,.0.00+

20,000100,00032,200,000

600,.000+

12,000,000

30,000+

57,000,000

100,000+

900,000

6,000,000700,000,000+

3,300,0.00

2,300,000

17,000,000

60,000+

1,400,000

2,000,000

14,300,000

6,400,000

350,.000

1,000,.000

15,00.0

1,000,.000

8.0,000+

17,000,000+

50,000+

56,000,000+

100,000+

900,000+

?

?

3,300,000

2,300,000

15,000

3,.000,000

'l

?

2,.oOQ,000+

60,,000

10.0,000+

1,200,000

215,0.0.0,000

200,000+

3.0,000+

31!,,015,OOO+

ENGLISH TODAY No. 1 - JANUARY 1985

SECOND LANGUAGE

SPEAKERS

/;

3,200,000

85,.000,000+

3,500,000

50,0.00,.000

6.00,000

6.0,000

3,600,0.00

2,500;000

200,000+

30,000,000

60,000

100,.000+

10.0,.0.00+

600,000

18,5.00,.000

100,000+

1,200,.000

80,000+

13,000,000

230,000,.0.00+

3.00,0.0.0100,000

150,0.00+

6,0.00,000

7,600,000

30,000

1,336,845,000+

Estimates of the number of English

users in the world. The first list gives

figures forthose who speak English

as a mother tongue, or first language.

The second list gives recent overall

population figures (usually 1981 or

thereabouts) for those cou ntries

where English has official status as a

medium of communication,

and

where people have learned itusually in school- as a second

language. These totals will generally

be overestimates. There are no

figures available for people who have

learned English as a foreign

language, in countries where the

language has no official status. I have

used a plus sign to mean' more than',

a minus sign to mean 'less than' ,and

a question mark in places where no

one knows how many first language

speakers there are.

here reach a total not far off a third of

the current world population. Has

this enormous jump in the estimates,

from 700 to 1400 million, any

justification?

Gunnemark and Kenrick do provide one clue that their total may be

less dramatic than it seems. Their

figure, they say, 'includes some 800

million inhabitants in countries

where English is an associated official

language (above all India)'. Ah,

India. A country whose population

increased by a quarter between 1971

and 1981. The 1983 population

estimate for India was 698 million - a

convenient figure for me to use in the

present discussion, as it relates very

nicely to the 700 million difference

cited above. Indeed, it is already an

underestimate, when we recall the

world growth rate of 1.8 per cent. Or,

to put this another way, if this article

takes you a quarter of an hour to read,

you must revise your estimate of India's

population upwards by 4,000.

'

The significance of India is ob

vious, when you look at the table of

countries where English has some

kind of official standing. No other

population estimate in the list gets

anywhere near that country's total.

Apart from one uncertain exception,

which I'll refer to shortly, whatever is

happening to English in India will be

the factor which decides whether our

total is nearer 700 or 1400 million. Or

perhaps this statement should be

broadened to include the whole of the

Indian subcontinent - that is, to

include Bangladesh (92.6m.), Pakistan (87.lm.), Sri Lanka (ls.2m.),

Nepal (ls.8m.), and Bhutan (1.2m.)

- all 1983 population estimates. Braj

Kachru adopts this broader perspective, fri his article on South Asian

English in the Bailey and G6rlach

collection. He points out that figures

for all the functions of English in all

the regions are not available, but he

cites a widely-used total of 3 per cent

of the population as 'English-knowing bilinguals' - that is, those 'who

can use English (more or less)

effectively in a situation' (p. 378).

Three per cent of around 900 million

is an easy sum: 27 million people.

Of course, it all depends what

'more or less' means. Kachru's

examples show that he is taking a

fairly conservative line here, considering only those who have an

educated awareness of the language.

He refers, for instance, to the 24.4

million students who are enrolled in

English classes, to the 23 percent of

the reading public who take an

English newspaper, to the 74 percent

of scientific journals published in

India in 1971. He points out that

English is the language of the legal

system, a major language in Parliament, and a preferred language in the

universities and all-India competitive

examinations for senior administrative, engineering and foreign service

positions. In terms of some such

notion as 'educated awareness' or

'fluent command' , we must accept his

figure of 3 percent, at least until a

better survey is carried out. But is this

the most relevant criterion?

I am struck by the remarkable

amount of semi-fluent or 'broken'

English which is encountered in the

Indian sub-continent, used by people

with a limited educational background. The important point to

appreciate is. that this is broken

English, not French, or Swahili, or

anything else. And just because it is

'broken' does not make it any the less

English. There is surely a sense in

which these people have a developing

awareness of the language which has

to be taken into account in any totals

of language in use? Everyone agrees

that it is difficult to define bilingual

competence - but why should the

only criterion for statistical inclusion

be educated excellence? Some lower

level of competence might just as

justifiably be proposed .

The usual response to this kind of

reasoning is the 'thin end of the

wedge' argument. If we allow in

speakers with only 90% competence,

why not 80%, or 50% or 5% ... ?

What about the many children,

running about India at this moment,

who have learned but a few English

words and phrases as part of their

restricted language of begging? Can

they be said to know English, in any

sense? My point is, they do not beg

with smatterings of Spanish, or

Russian, or Chinese. A French visitor

told me that he was approached in

this way, and he held an effective

conversation with some of these

children in a pidgin English of their

devising. They had no pidgin

French. Is this kind of competence to

be ignored totally, in discussing

speaker estimates?

.

It usually is, but I think we are

wrong to do so. There is a sense in

which English is the language of most

of the population of the subcontinent. It is a language which is

part of their cultural milieu, which

rubs off onto them in all kinds of

ways, and which many will have some

primitive, native, systematic awareness of. The important point to stress

here is that the awareness must be

'systematic' - that is, something more

than simple rote learning of individual lexical items, involving some

degree of generalization in phonology

and grammar. If we use this criterion

to replace the criterion of 'fluent

command', then I wonder just how

much of the population would have to

be included? Half? Two-thirds?

I don't think I would want to use

the same flexible criterion for countries where English has no official

status. Doubtless there are people in

all parts of the world who have

developed a smattering of English for

trade and other purposes. After all,

this is how the pidgin Englishes of the

world emerged in the first pla~e. An

important constraint on the ciiterion

is that the language must be a

culturally significant element. There

must be an element of genuine

'nativeness' in the learning context.

There also has to be a learning

continuum available for people to

follow - at least in principle, should

opportunity permit.

On this basis, we could perhaps

accept Gunnemark and Kenrick's

figure. But could we ever go beyond

it? The field of teaching English as a

foreign language is ripe for serious

study. What is amazing is that there

are no reliable figures available for the

number of learners under this heading - even for Europe. While

preparing this article, I thought that

at least the member states of the

European Economic Community

would have some data available.

None of them have. Against this must

be set such quasi-facts as the

following. English radio programmes

are received by 150 million people in

over 120 countries. 100 million

receive programmes from the BBC

External Service. The tip of how large

an iceberg?

And all of this is but the beginning,

for we have to take into account the

uncertain exception which I referred

to earlier, and which I have so far

conspicuously ignored - China. In

1983, around 100 million Chinese

watched the BBC television series on

the English language, Follow Me. As

far as I know, the Chinese were not

watching similar programmes in

French, German or Arabic. China has

always been excluded from the

statistical reviews, because of the

shortage of information from inside

the country. Bilt these days, because

of the numbers involved, special

efforts should be made to obtain

accurate information from there. The

total number of English learners as a

foreign language doubles, when the

Chinese are taken into account. Or

quadruples, if we do not insist on the

passing of an English language

examination as a standard of entry.

So, if you are highly conscious of

international standards, or wish to

keep the figures for world English

down, you will opt for a total of

around 700 million, in the mid 1980s.

If you go to the opposite extreme, and

allow in any systematic awareness,

whether in speaking, listening, reading or writing, you could easily

persuade yourself of the reasonableness of 2 billions. I am happy to settle

for a billion, myself, but would

welcome comment as to whether I am

being too conservative or too radical.

If the criticisms balance, I shall stay

with this figure for a while.

fEij

~:

Bailey

and M. <J6rlach (eds.),

EriJ!/fshas a World Limguage.

: C.U.P. 19134.

;j~i5Qfl1an,~,L.C00per and

~W. Cgnraf! (eds.), The Spread of

h :theoci%gy

of English as

'ditio~a~.Language. Rowl~y,

w~b!y\Hou5e.1977.

rk anf! D:' Kenrick, What

~{fySpeak?Kinna,

. rk (private

ENGLISH TODAY No. 1 - JANUARY 1985

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Easy Ladino Songs Sheet MusicDokument16 SeitenEasy Ladino Songs Sheet MusicEmir Asad100% (2)

- Time for Grammar Basic 학생용 PDFDokument176 SeitenTime for Grammar Basic 학생용 PDFEvelyn Jung100% (1)

- Introduction To Arabic Natural Language ProcessingDokument186 SeitenIntroduction To Arabic Natural Language ProcessingBee Bright100% (1)

- Barack Obama Adjectives To Describe People PDFDokument2 SeitenBarack Obama Adjectives To Describe People PDFmaiche amar100% (2)

- Late Modern EnglishDokument3 SeitenLate Modern EnglishCarmen HdzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phrasal Verbs in Context by Peter DaintyDokument70 SeitenPhrasal Verbs in Context by Peter DaintyNhy Yến100% (1)

- Pronoun: Personal Subjective Objective Possessive Adjective Possessive Pronoun MeaningDokument3 SeitenPronoun: Personal Subjective Objective Possessive Adjective Possessive Pronoun MeaningNeni ChandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV Vocabulary HandoutDokument1 SeiteCV Vocabulary HandoutLauraNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Makes a Word RealDokument5 SeitenWhat Makes a Word RealleontankxNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNIT 1: Towns and Cities: PBD Vocabulary 1Dokument12 SeitenUNIT 1: Towns and Cities: PBD Vocabulary 1NBRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Irregular Verbs - PART 1Dokument5 SeitenIrregular Verbs - PART 1EY11-2T WARIERONoch keine Bewertungen

- Decide True/False Phonetic StatementsDokument1 SeiteDecide True/False Phonetic Statementsmar_43Noch keine Bewertungen

- Past Continuous Ingles 2Dokument1 SeitePast Continuous Ingles 2Vanesa Garcia GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Origin of Apsara PDFDokument1 SeiteThe Origin of Apsara PDFBineet KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theme and Variations PDFDokument12 SeitenTheme and Variations PDFChance CaprarolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Onset: The Beginning Sound of A Syllable, Preceding The Peak. These Are Always ConsonantsDokument2 SeitenOnset: The Beginning Sound of A Syllable, Preceding The Peak. These Are Always ConsonantsMariposa RosadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Present Tense Presentation......Dokument19 SeitenPresent Tense Presentation......wannabe5855100% (2)

- Past Tense Verbs in ArabicDokument54 SeitenPast Tense Verbs in ArabicThomas SatkinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- IE9 Tracking Protection ListDokument132 SeitenIE9 Tracking Protection ListtushpusherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Past Simple of Be 4th Grade 2023Dokument2 SeitenPast Simple of Be 4th Grade 2023ritasusanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 40 42Dokument7 SeitenLesson 40 42RadhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal Reading KelasDokument2 SeitenSoal Reading KelasIrma SasmitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AP5 Q1 Mod6 Sosyo Kultural at Politikal Na Pamumuhay v5Dokument20 SeitenAP5 Q1 Mod6 Sosyo Kultural at Politikal Na Pamumuhay v5Wilmar MondidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prathama Vibakthihi (Nominative Case)Dokument2 SeitenPrathama Vibakthihi (Nominative Case)AmritaRupini100% (1)

- SocipaperDokument7 SeitenSocipaperQomaRiyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vocabulary Words Mid Term ExamDokument9 SeitenVocabulary Words Mid Term Examahmed hussienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claimed Circulation of Big Periodicals in IndiaDokument159 SeitenClaimed Circulation of Big Periodicals in IndiasunilchanderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answers With ExplanationsDokument2 SeitenAnswers With ExplanationsRenz Daniel Fetalvero DemaisipNoch keine Bewertungen

- About Arabic LanguageDokument6 SeitenAbout Arabic LanguagenabusaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blueprint Unit Test-Ii Subject: English Class Iii SESSION: 2020-2021 NAME: - Time: 1 Hour DATEDokument2 SeitenBlueprint Unit Test-Ii Subject: English Class Iii SESSION: 2020-2021 NAME: - Time: 1 Hour DATEPushpa DeviNoch keine Bewertungen