Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Malcolm Pines - The Group-As-A-whole Approach in Foulksian Group Analytic Psychotherapy

Hochgeladen von

Nacho Vidal NavarroOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Malcolm Pines - The Group-As-A-whole Approach in Foulksian Group Analytic Psychotherapy

Hochgeladen von

Nacho Vidal NavarroCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

THE GROUP-AS-A-WHOLE A P P R O A C H IN

F O U L K S I A N G R O U P ANALYTIC P S Y C H O T H E R A P Y

Malcolm Pines

The group analytic group-as-a-whole approach of Foulkes privileges

the concept of the group matrix. The term matrix is a metaphor for

"the network of all individual mental processes, the psychological

medium in which they meet, communicate, and interact." The developing group matrix acts both as a container and as a holding

environment for the psychic processes of the individual members in

the group context. The concept of coherency is evoked to describe the

process of the developing capacity of a group to be therapeutic. The

concept of coherency is applied both to conscious and to unconscious

mental process.

I shall organize my discussion around the theme of coherency, which I define

as "the meaningful organization of~parts that make a whole." I hope to make

my reasons for doing so clear and to show that the concept of coherency underlines and informs the concept of wholeness, which is intrinsic to the concept

of the group-as-a-whole.

Psychodynamic processes represent effort to make the organization of the

psychotherapeutic situation meaningful, therefore coherent. We take as our

data the set-up of patient and therapist.

In psychoanalysis the enterprise to un-cover and dis-cover underlining meanings in the psychoanalytic discourse produced by the basic rule of free association is governed by a conviction that it is possible to raise, apparently at

random, associations originating from a deeper level of consciousness, closer

to the primary process, than to the higher levels of secondary process organization, therefore of coherency.

We ask our patients to tell us their life stories, that is, we join them in a

narrative enterprise. When the life story of the patient fails to present a

mysterious incoherence, Freud regarded this as a sign that the neurotic process

was not present. As therapists we assume that a person's life has a story, that

the narrative will include both the self and significant others, that there will

be beginnings, middles and endings, causes, sequences, and some sense of

purpose. The defenses of our patients may range from the presentation to us

of an apparently complete story that has the effect of knocking the beginning

of a new story, the therapeutic enterprise; other patients will come with no

Address correspondence to: Malcolm Pines, 1 Daleham Gardens, London NW3, 5BY, England.

212 / GROUP, Volume 13, Numbers 3 & 4, Fall/Winter, 1989 Brunner/Mazel, Inc.

Group-as-a-Whole in Foulksian Group Analytic Psychotherapy / 213

story at all to tell, and then our task is to bring the person into a position of

being able to tell a story, to begin to play, as Donald Winnicott pointed out.

Our best patients are those who bring an interesting but mysterious story

which unfolds session by session and which holds the attention both of patient

and of therapist as we share the darkness of the unconscious processes of mind.

A great deal of our current discourse consists of metaphors which, according

to Lakoff and Johnson, are not mere linguistic devices. Our h u m a n thought

processes are largely metaphorical; there are metaphors in our conceptual

systems and metaphors bind elements into coherent systems. The "as if-ness"

of things is a key element of our therapeutic endeavor, but through this we

are able to move with our patients into a new mental space where the dynamics

of therapy intermesh with the internalized dynamics of the patient's life development.

Progress in psychotherapeutic theory is fundamentally our capacity to devise

new metaphors which will hold and contain our experiences and make them

intelligible to our peers. Each new field of endeavor both borrows from a

cultural vernacular and attempts to breathe new life into it, to suit its own

needs. The psychoanalytic paradigm was constructed at the turn of the century

and was based on evolutionary, geological, archaeological and energic physical

metaphors. Thus, the instinctual forces, originating in the primitive levels of

mind and of life experience, exert upward pressure on the higher levels of

organization, which resist this upsurge with downward pressure. The psychic

apparatus is organized to maintain a low level of mental stimulation; the

cultural restraints of society block a gratification of narcissistic and instinctual

satisfactions, and these restraints become internalized as the super ego. The

struggle to create new metaphors more consonant with present day concepts

of the organization of psychic life accounts for the turmoil within psychoanalytic theorizing.

Psychoanalytic theory has been based on Rickman's one-body psychology to

a large extent. The application of these concepts to the group field did not

represent the conceptual shift that was necessary to grasp the nature of the

new therapeutic situation of a number of persons meeting together with a

therapist, which was a new social contrivance. What the paradigm shift needed

was a field theory and this came from gestalt psychology, principally through

the work of Kurt Lewin. Gestalt psychology developed to oppose faculty psychology and emphasized the wholeness of perception. Lewin transposed this

approach to psychology of the person, the individual situated in and moving

through a life space, the psychological field where all psychic events occur.

The person and the environment are viewed as one constellation of interdependent factors. The Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset gives as an answer

to the question "Who am I?": "I am myself plus my circumstances." Thus, man

is situated in his environment, and that which stands around him, his circumstances, are essential to a dynamic social psychology that situates the person

firmly in his or her environment and that will not perform the fallacy of an

arbitrary division of the essential unity that is man-in-the-world.

The 1920s and 1930s saw the rise of social and industrial psychology and

of new attempts to conceptualize an interpersonal psychology that could account adequately for the complexity of h u m a n life in h u m a n society. Sociology

and anthropology mated with psychodynamics and produced a much greater

appreciation of the collosal forces of society that penetrate the individual to

the very core. We came to appreciate that the Western individual of the 20th

century significantly differs from his ancestors because he is born into a different sociocultural matrix from that of his forefathers, for the social matrix

214 / GROUP, Volume 13, Numbers 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 1989

structures and moulds the basic drives from conception onwards. This Foulkes

termed the Foundation Matrix.

The importance of language in capturing experience and in making it available for thought and for speech is a psychosocial factor of prime significance

and needs to be seen on a par with the significance of biological constitution.

This is expressed in the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

In the same era Trigant Burrow began his long odyssey to explore and to

describe group psychology and the social basis of consciousness. His work is

a largely unseen background to much later work in social psychology and

group psychotherapy. Burrow's work was known to Foulkes, through his work

with Kurt Goldstein, and he was also aware of Kurt Lewin's approach. However, we should credit Foulkes with the most original and striking articulation

of the group-as-a-whole approach.

Foulkes' definition enables us to hold the background/foreground gestalt

concept that both individual and group, group and individual are represented

in the therapist's observational field. This therapeutic approach is a natural

development from a foundation both emerging from and imbedded within a

matrix.

"The network of all individual mental processes, the psychological medium

in which they meet, communicate, and interact, can be called the matrix. This

of course is a construct--in the same way as is, for example, the concept of

traffic, or for that matter of mind . . . . There can be no question of a problem

of group versus individual, or individual versus group. These are two aspects,

two sides of the same coin." This fundamental attitude must arise from an

integrated intellectual and emotional attitude, a conviction best obtained in

a group analytic training. This will guide the therapist and will enable him/her,

acting as group conductor, to trust the group.

What does this m e a n - - t o trust the group? To me, it means that I profoundly

believe that when working with a reasonably well-selected group, we shall

both explore and resolve whatever dynamic issues arise in the course of group

discussion. Our understanding of the analytic group's capacity to accomplish

this is represented in Foulkes' Basic Law of Group Dynamics.

The deepest reason why patients can reinforce each other's normal reactions and wear down and correct each other's neurotic reactions is that

collectively they constitute the very norm from which individually they

deviate. Each individual is to a large extent part of the group to which

he belongs and this collective aspect permeates all through to his very

core. In so much that he deviates from the norm of his group he is a

variant of it and it is this very deviation that makes him into a unique

individual. Thus, within a group, individuality manifests itself as variations upon a common ground. The sound part of individuality is both

supported in a group, and, as a therapeutic culture develops, the further

growth of healthy individuality is approved and supported by the group

as a whole. Neurotic processes, that is symptoms and neurotic aspects of

individuality, diminish as their individual meanings become communicated and understood, both by the patient and by the other members of

the g r o u p . . .

The group can only grow by what it can share and only share what it

can communicate and only "communicate" by what it has in common,

e.g., in language, that is, on the basis of the community at large. In that

sense group treatment means applying "commonsense"--a sense of the

Group-as-a-Wholein Foulksian GroupAnalyticPsychotherapy/ 215

community--to a problem by letting all those openly participate in its

attempted solution who are in fact involved in it.

In the language of information theory, when individual organisms come together to form a group, we have a vastly enriched informational structure. It

is through this that the group develops the capacity to achieve new and higher

levels of integration and differentiation, greater than that of the ordinary

individual, especially if he/she is held together by neurotic structures that

resist change by repelling new information. In the group analytic situation,

neurotic structures can be seen as obstacles to the development of new and

progressive forms and levels of communication. Defensive maneuvers show as

figures against the ground of the group dynamic matrix, which essentially

deepens and enriches the personal experience of the individual group members.

Rationalization, denial, projection, and repression become clear to the other

group members because they impinge on their personal relationships with

each other and can be seen to affect the group process. Resistances to selfunderstanding are greater than resistances to understanding others, for we

are less threatened by their conflicts and better able to perceive them. Thus,

each person inevitably takes a part in the evolution of group life, which,

hopefully, widens the range of understanding of each person through the much

greater and wider range of information that is available to the group-as-awhole. The group process shows a rhythm and polarity between integration

and differentiation. Differentiation arises through the uniqueness of individuals, integration through their commonality. The integration that comes about

through the working through of diversity and conflict represents the achievement of coherency, and the experience of working toward and achieving this

coherency becomes laid down in the dynamic group matrix. We can conceive

of the coherency that is reached through the work of the group and the conductor, for instance, by the recognition of common group themes, as raising

the level of understanding and adaptation to a higher common denominator

than that which would be achieved were a therapeutic attitude absent. This

therapeutic attitude must constantly come from the conductor, but very important contributions to it will come from the group members.

A basic function of the group-as-a-whole is to hold and contain psychic proce s s e s - t h e thoughts, feelings and attitudes of its members--which appear as

foreground against the background of the group situation. Holding and containing are valuable metaphors, which have only entered into our terminology

comparatively recently, as we have widened and deepened our knowledge both

of the therapeutic situation and of psychic development in infancy. We use

these metaphors to describe and to understand basic maternal functions. Holding comes from Winnicott, for whom holding is the basis for becoming a self

experiencing thing, and reliable holding has to be a feature of the environment

for the going-on-being of the infant. The environment, environmental mother,

and object mother provide a continuation of physiological provisions of the

prenatal state. The mother has to manage the extrauterine matrix and understand the needs of the infant, both physiological and psychological, and

provide both protection from physiological insult and from overstimulation

and the optimal stimulation that is needed for development. Mother is caregiver and can be replaced by other caregivers, but the basic requirements must

be met. Holding is a metaphor based on physical experiences that coherently

brings together a whole variety of maternal acts and attitudes.

The notion of containment comes from Wilfrid Bion, whose model of the

container and the contained has extended our grasp of early mother/infant

216 / GROUP, Volume 13, Numbers 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 1989

relationships. The infant's primitive affects and anxieties are taken in, understood and dealt with by the caregiver's intuitive capacities for containment.

The processes of intuition, empathy, and active ministrations can be characterised coherently through the metaphor of containment. Both mother and

infant are containers of psychic events and processes of exchange take place

continually between them, mother having the capacity to contain and to transform primitive infantile states of being and to hand them back to the infant

at a higher level of process and integration. In the group situation, these are

the functions of the group-as-a-whole.

There is an essential paradox in the group situation. These basic functions

of holding and containment coexist with a culture that is based on analysis

and translation, which are sophisticated higher levels of mental functioning.

Thus, there are inherent contradictions in the group situation, a delicate,

stable yet unstable balance that has constantly to be monitored and managed.

Early developmental processes reenacted in the group can be held, contained

and tolerated as the group can function at a higher level and is available to

the individuals, often more adequately and appropriately than were the containers and holders of the patient's early experienes. Thus the members develop

their capacity to think in the face of pain and to tolerate and to know the

unthinkable.

So finally I come to an attempt to define the group-as-a-whole in group

analytic terms: It is the basic concept underlying the approach to a group that

meets in a standard group analytic situation, which privileges communication,

and in which the therapeutic aim is to enable both individual a n d group coherency to emerge over time at both conscious and unconscious levels. Increased

unconscious coherency represents the establishment and enrichment of the

group matrix. The conscious coherency comes as a result of the working out

of interpersonal issues that arise inevitably in the group situation.

I have written elsewhere about the principle of coherency and will briefly

review the main issues. Freud described the ego as a "coherent organisation

of mental processes." This applies both at the conscious and the unconscious

levels. It is Loewald who has pointed out that Freud makes the important

distinction between a coherent unconscious and the repressed unconscious.

The unconscious is not an area of chaos and incoherency. Those attributes

belong to the repressed unconscious but not all that is unconscious is repressed

and in an incoherent state. Loewald maintains: (a) What is internalized becomes an inherent part of a coherent ego which has both conscious and unconscious aspects. (b) What is repressed is split off in the coherent ego. (c) We

must distinguish between the processes of repression and the processes of

internalization. The latter are involved in creating and increasing the coherent

integration and organization of the psyche as a whole, whereas repression

works against such coherent psychic organization by maintaining a share of

psyche processes in a less organized, more primitive state.

These are the processes we increasingly recognize are involved in infant

caregiver transactions and that lay down the matrix of personality and social

capacity. The group-as-a-whole concept presages these findings and encourages

us in our search to extend and amplify the study of these processes both in

infancy and at all developmental levels in both social and individual psychology.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- GR 1103 EvansDokument14 SeitenGR 1103 EvansJoão Vitor Moreira MaiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gestalt, Psy PDFDokument17 SeitenGestalt, Psy PDFAdriana Bogdanovska ToskicNoch keine Bewertungen

- European Psychotherapy 2016/2017: Embodiment in PsychotherapyVon EverandEuropean Psychotherapy 2016/2017: Embodiment in PsychotherapyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friedrich Pearls - Life SummaryDokument5 SeitenFriedrich Pearls - Life SummaryManish SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Paranoid-Schizoid and Depressive PosDokument9 SeitenThe Paranoid-Schizoid and Depressive PosHermina ENoch keine Bewertungen

- Group Therapy Techniques Derived from PsychoanalysisDokument12 SeitenGroup Therapy Techniques Derived from PsychoanalysisJuanMejiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis: Of: Group Sights Conscious UnconsciousDokument13 SeitenAnalysis: Of: Group Sights Conscious UnconsciousJoão AfonsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Object Relations Group PsychotherapyDokument6 SeitenObject Relations Group PsychotherapyJonathon BenderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Melanie Klein Origins of TransferanceDokument8 SeitenMelanie Klein Origins of TransferanceVITOR HUGO LIMA BARRETONoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflections On ShameDokument21 SeitenReflections On ShameAnamaria TudoracheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalytic Theories of PersonalityDokument29 SeitenPsychoanalytic Theories of PersonalityAdriana Bogdanovska ToskicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approaching Countertransference in Psychoanalytical SupervisionDokument33 SeitenApproaching Countertransference in Psychoanalytical SupervisionrusdaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Working With Trauma Lacan and Bion ReviewDokument5 SeitenWorking With Trauma Lacan and Bion ReviewIngridSusuMoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mirroring in Movement Dance Movement The PDFDokument35 SeitenMirroring in Movement Dance Movement The PDFТатьяна ПотоцкаяNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stern, D.N., Sander, L.W., Nahum, J.P., Harrison, A.M., Lyons-Ruth, K., Morgan, A.C., Bruschweilerstern, N. and Tronick, E.Z. (1998). Non-Interpretive Mechanisms in Psychoanalytic Therapy- The Something MoreDokument17 SeitenStern, D.N., Sander, L.W., Nahum, J.P., Harrison, A.M., Lyons-Ruth, K., Morgan, A.C., Bruschweilerstern, N. and Tronick, E.Z. (1998). Non-Interpretive Mechanisms in Psychoanalytic Therapy- The Something MoreJulián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RoleProfilesAIP LandyDokument12 SeitenRoleProfilesAIP LandyEvgenia Flora LabrinidouNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Kleinian Analysis of Group DevelopmentDokument11 SeitenA Kleinian Analysis of Group DevelopmentOrbital NostromoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Williams (1999) Non-Interpretive Mechanisms inDokument16 SeitenWilliams (1999) Non-Interpretive Mechanisms inLoratadinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Education of The Drama Therapist: in Search of A GuideDokument18 SeitenThe Education of The Drama Therapist: in Search of A GuideEvgenia Flora LabrinidouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carpy - Tolerating The CountertransferenceDokument8 SeitenCarpy - Tolerating The CountertransferenceEl Karmo San100% (1)

- On Misreading and Misleading Patients: Some Reflections On Communications, Miscommunications and Countertransference EnactmentsDokument11 SeitenOn Misreading and Misleading Patients: Some Reflections On Communications, Miscommunications and Countertransference EnactmentsJanina BarbuNoch keine Bewertungen

- EnactmentDokument20 SeitenEnactmentCamelia Dracsineanu GheorghiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roubal 2012 Three Perspectives Diagnostic ModelDokument34 SeitenRoubal 2012 Three Perspectives Diagnostic ModelGricka DzindzerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coping CancerDokument28 SeitenCoping CancerCharlene TomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalytic Supervision Group, IndianapolisDokument1 SeitePsychoanalytic Supervision Group, IndianapolisMatthiasBeierNoch keine Bewertungen

- HinshelwoodR.D TransferenceDokument8 SeitenHinshelwoodR.D TransferenceCecilia RoblesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Payment PDFDokument35 SeitenPayment PDFLauraMariaAndresanNoch keine Bewertungen

- DREAMSDokument148 SeitenDREAMSJavier Ugaz100% (1)

- On Language and Truth in PsychoanalysisDokument16 SeitenOn Language and Truth in PsychoanalysisAlberto JaramilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Becoming a Postmodern Collaborative TherapistDokument31 SeitenBecoming a Postmodern Collaborative TherapistManuel Enrique Huertas RomanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pontalis, J. B. (2014) - No, Twice NoDokument19 SeitenPontalis, J. B. (2014) - No, Twice NocabaretdadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On Some Schizoid MechanismsDokument20 SeitenNotes On Some Schizoid MechanismsJade Xiao100% (1)

- The Phenomenology of TraumaDokument4 SeitenThe Phenomenology of TraumaMelayna Haley0% (1)

- Brown, S. F. - What Do Mothers Want - Developmental Perspectives, Clinical Challenges-Routledge (2005)Dokument299 SeitenBrown, S. F. - What Do Mothers Want - Developmental Perspectives, Clinical Challenges-Routledge (2005)E AranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supportive Psychotherapy 2014Dokument3 SeitenSupportive Psychotherapy 2014Elizabeth Paola CabreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transactional Analyst Theory on Impasse and TransferenceDokument2 SeitenTransactional Analyst Theory on Impasse and Transferencedhiraj_gosavi8826Noch keine Bewertungen

- 112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Dokument20 Seiten112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Paula GonzálezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rogers and Kohut A Historical Perspective Psicoanalytic Psychology PDFDokument21 SeitenRogers and Kohut A Historical Perspective Psicoanalytic Psychology PDFSilvana HekierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fear of SuccessDokument11 SeitenFear of SuccessabelardbonaventuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hoffman - The Myths of Free AssociationDokument20 SeitenHoffman - The Myths of Free Association10961408Noch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction To GestaltTherapyDokument8 SeitenAn Introduction To GestaltTherapyLuis MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Informational Value of The Supervisor'sDokument13 SeitenThe Informational Value of The Supervisor'sv_azygos100% (1)

- Blatner A Las Multiples Caras Del PsicodramaDokument13 SeitenBlatner A Las Multiples Caras Del PsicodramastellasplendersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive Theories of Learning: Gestalt and Field TheoryDokument35 SeitenCognitive Theories of Learning: Gestalt and Field TheoryGene RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joseph D. Lichtenberg, The Clinical Exchange - Techniques DerivedDokument240 SeitenJoseph D. Lichtenberg, The Clinical Exchange - Techniques DerivedForgáchAnna100% (1)

- Bion and Foulkes at NorthfieldDokument10 SeitenBion and Foulkes at Northfieldkkarmen760% (1)

- BGJ V1N2Dokument60 SeitenBGJ V1N2Maja PetkovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thepsychodynamic Treatmentofborderline Personalitydisorder: An Introduction To Transference-Focused PsychotherapyDokument17 SeitenThepsychodynamic Treatmentofborderline Personalitydisorder: An Introduction To Transference-Focused PsychotherapyDonald Cabrera AstudilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winnicott ch1 PDFDokument18 SeitenWinnicott ch1 PDFAlsabila NcisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Free AssociationDokument13 SeitenFree AssociationKimberly Mason100% (1)

- Using The Imagination in Gestalt Therapy - Dreams IAHIPDokument5 SeitenUsing The Imagination in Gestalt Therapy - Dreams IAHIPmeroveoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalysis PDFDokument6 SeitenPsychoanalysis PDFHamna AroojNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bion - Attacks On LinkingDokument17 SeitenBion - Attacks On LinkingUriel García VarelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Moon Is Made of Cheese. Exercises of PDFDokument52 SeitenThe Moon Is Made of Cheese. Exercises of PDFAnonymous PIUFvLMuVONoch keine Bewertungen

- Domenico Consenza Body and Language in Eating DisordersDokument26 SeitenDomenico Consenza Body and Language in Eating Disorderslc49Noch keine Bewertungen

- Codependence: A Transgenerational Script: Gloria Noriega GayolDokument11 SeitenCodependence: A Transgenerational Script: Gloria Noriega GayolMaritza HuamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- AEDP REFERENCESFoshaDokument6 SeitenAEDP REFERENCESFoshaDave HenehanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greenson 1953Dokument15 SeitenGreenson 1953Sheila M. CedeñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Esalen's Resident Alien: Secular Sceptic in a Utopian CommunityVon EverandEsalen's Resident Alien: Secular Sceptic in a Utopian CommunityBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Peripatetic Group Therapy Phenomenology and PsychopathologyVon EverandPeripatetic Group Therapy Phenomenology and PsychopathologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cybernetics PaperDokument15 SeitenCybernetics PaperNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bridging The Transmission GapDokument12 SeitenBridging The Transmission GapEsteli189Noch keine Bewertungen

- Age of PsychopathyDokument82 SeitenAge of PsychopathyNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seikkula-Makingsense 1012Dokument21 SeitenSeikkula-Makingsense 1012Nacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Borderline-Greenberg - The 5 QuestionssDokument10 SeitenBorderline-Greenberg - The 5 QuestionssIvana100% (2)

- Promoting Recovery First Episode PsychosisDokument88 SeitenPromoting Recovery First Episode PsychosisNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Searles Oedipal Love in The CountertransfDokument10 SeitenSearles Oedipal Love in The CountertransfNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Howell E. The Dissociative Mind Intro and Chap1 Pp1 37Dokument19 SeitenHowell E. The Dissociative Mind Intro and Chap1 Pp1 37Nacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- CCR T Pervasive NessDokument15 SeitenCCR T Pervasive NessNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- OpenDialog ApproachAcutePsychosisOlsonSeikkulaDokument16 SeitenOpenDialog ApproachAcutePsychosisOlsonSeikkulaAlejandra Márquez CalderónNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seikkula-Makingsense 1012Dokument21 SeitenSeikkula-Makingsense 1012Nacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maj 2015 - ISPS-dk - DK: Professor Paul LysakerDokument20 SeitenMaj 2015 - ISPS-dk - DK: Professor Paul LysakerNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seikkula-Makingsense 1012Dokument21 SeitenSeikkula-Makingsense 1012Nacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attachment Clinical PerspectivesDokument8 SeitenAttachment Clinical PerspectivesNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stolorow R Ch.7 The Difficult Patient in The Intersubjective PerspectiveDokument11 SeitenStolorow R Ch.7 The Difficult Patient in The Intersubjective PerspectiveNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casement Mistakes in PsychoanalysisDokument9 SeitenCasement Mistakes in PsychoanalysisNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Akhtar 1982Dokument5 SeitenAkhtar 1982Nacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patients WardDokument9 SeitenPatients WardNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benjamin Master and SlaveDokument18 SeitenBenjamin Master and SlaveNacho Vidal Navarro0% (1)

- 215Dokument8 Seiten215Nacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gunderson MilieuDokument9 SeitenGunderson MilieuNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kernberg O.F. Ch.1 Object Relations Theory and Clinical Psychoa1Dokument20 SeitenKernberg O.F. Ch.1 Object Relations Theory and Clinical Psychoa1Nacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- E1f 9 Ghent E MasochismDokument16 SeitenE1f 9 Ghent E MasochismMarkWoodxxxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greenberg & Mitchell Object RelationsDokument7 SeitenGreenberg & Mitchell Object RelationsNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atwood G. Ch.1 Faces in A CloudDokument16 SeitenAtwood G. Ch.1 Faces in A CloudNacho Vidal Navarro100% (1)

- 19.1lysaker OCRDokument21 Seiten19.1lysaker OCRNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fosshage Article1 PDFDokument24 SeitenFosshage Article1 PDFCarlos DevotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Need To Have Enemies and Allies - Jerrold PostDokument30 SeitenThe Need To Have Enemies and Allies - Jerrold PostNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alliance BriefDokument22 SeitenAlliance BriefNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Borderline HospitalizedDokument16 SeitenBorderline HospitalizedNacho Vidal NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agents & Environment in Ai: Submitted byDokument14 SeitenAgents & Environment in Ai: Submitted byCLASS WORKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotional Self-Management in ChildrenDokument11 SeitenEmotional Self-Management in Childrenesther jansen100% (1)

- Technical Writting McqsDokument4 SeitenTechnical Writting Mcqskamran75% (4)

- Michigan Standards For The Preparation of School PrincipalsDokument28 SeitenMichigan Standards For The Preparation of School Principalsapi-214384698Noch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Information SystemDokument14 SeitenMarketing Information SystemgrameNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 HandbookDistanceLearningDokument15 SeitenChapter 4 HandbookDistanceLearningKartika LesmanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Strategies and SkillsDokument6 SeitenReading Strategies and SkillsDesnitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kindergarten LP-Q3-Week 1-Day 1Dokument2 SeitenKindergarten LP-Q3-Week 1-Day 1Sharicka Anne Veronica TamborNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detailed Lesson Plan Skimming ScanningDokument6 SeitenDetailed Lesson Plan Skimming ScanningDina Valdez90% (20)

- Paradox and ParaconsistencyDokument15 SeitenParadox and Paraconsistency_fiacoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Booklet 2021 Past Papers 2020 and VocabularyDokument243 Seiten1 Booklet 2021 Past Papers 2020 and Vocabularyjuan alberto zielinskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9781315773971Dokument293 Seiten9781315773971龚紫薇100% (1)

- TIME Mental Health A New UnderstandingDokument22 SeitenTIME Mental Health A New UnderstandingKarina DelgadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Rating Prediction Using Yelp DatasetDokument2 SeitenReview Rating Prediction Using Yelp DatasetInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample FormatDokument15 SeitenSample Formatangelo carreonNoch keine Bewertungen

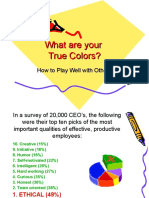

- What Are Your True Colors?Dokument24 SeitenWhat Are Your True Colors?Kety Rosa MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Criticism ApproachDokument3 SeitenLiterary Criticism ApproachDelfin Geo Patriarca100% (1)

- Workbook Smart Choice Unit 5Dokument5 SeitenWorkbook Smart Choice Unit 5Raycelis Simé de LeónNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing A Good Research QuestionDokument5 SeitenWriting A Good Research QuestionAhmad AsyrafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bell 2010Dokument8 SeitenBell 2010RosarioBengocheaSecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Usability TestingDokument6 SeitenChapter 4 Usability TestingRandudeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Learning Plan IlpDokument9 SeitenIndividual Learning Plan Ilpapi-358866386100% (1)

- Moneyball Seminario 2Dokument33 SeitenMoneyball Seminario 2robrey05pr100% (1)

- English For Engineering 2: Design and DrawingDokument11 SeitenEnglish For Engineering 2: Design and DrawingAriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LegoDokument30 SeitenLegomzai2003Noch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Research 2 Week 5 ProblemDokument12 SeitenPractical Research 2 Week 5 ProblemLuisa Rada100% (1)

- Comparatives Superlatives Worksheet With Answers-8Dokument1 SeiteComparatives Superlatives Worksheet With Answers-8Ismael Medina86% (7)

- PERRELOS NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 2ND QUARTER IMM SCORESDokument5 SeitenPERRELOS NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 2ND QUARTER IMM SCORESLUCIENNE S. SOMORAY100% (1)

- MWL101 - Task 2Dokument16 SeitenMWL101 - Task 2LiamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fs2 Course - Task List: Field Study 2Dokument4 SeitenFs2 Course - Task List: Field Study 2ROEL VIRAYNoch keine Bewertungen