Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

r1 JPPR 1225 Review

Hochgeladen von

Dinesh KumarOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

r1 JPPR 1225 Review

Hochgeladen von

Dinesh KumarCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Online Proofing System Instructions

The Wiley Online Proofing System allows authors and proof reviewers to review PDF proofs, mark corrections, respond

to queries, upload replacement figures, and submit these changes directly from the PDF proof from the locally saved file

or while viewing it in your web browser.

1. For the best experience reviewing your proof in the Wiley Online

Proofing System please ensure you are connected to the internet.

This will allow the PDF proof to connect to the central Wiley Online

Proofing System server. If you are connected to the Wiley Online

Proofing System server you should see the icon with a green check

mark above in the yellow banner.

Connected

Disconnected

2. Please review the article proof on the following pages and mark any

corrections, changes, and query responses using the Annotation Tools

outlined on the next 2 pages.

3. To save your proof corrections, click the Publish Comments

button appearing above in the yellow banner. Publishing your

comments saves your corrections to the Wiley Online Proofing

System server. Corrections dont have to be marked in one sitting,

you can publish corrections and log back in at a later time to add

more before you click the Complete Proof Review button below.

4. If you need to supply additional or replacement files bigger than

5 Megabytes (MB) do not attach them directly to the PDF Proof,

please click the Upload Files button to upload files:

Click Here

5. When your proof review is complete and you are ready to submit corrections to the publisher, please click

the Complete Proof Review button below:

Click Here

IMPORTANT: Do not click the Complete Proof Review button without replying to all author queries found on

the last page of your proof. Incomplete proof reviews will cause a delay in publication.

IMPORTANT: Once you click Complete Proof Review you will not be able to publish further corrections.

USING e-ANNOTATION TOOLS FOR ELECTRONIC PROOF CORRECTION

Once you have Acrobat Reader open on your computer, click on the Comment tab at the right of the toolbar:

This will open up a panel down the right side of the document. The majority of

tools you will use for annotating your proof will be in the Annotations section,

pictured opposite. Weve picked out some of these tools below:

1. Replace (Ins) Tool for replacing text.

2. Strikethrough (Del) Tool for deleting text.

Strikes a line through text and opens up a text

box where replacement text can be entered.

How to use it

Strikes a red line through text that is to be

deleted.

How to use it

Highlight a word or sentence.

Highlight a word or sentence.

Click on the Replace (Ins) icon in the Annotations

section.

Click on the Strikethrough (Del) icon in the

Annotations section.

Type the replacement text into the blue box that

appears.

3. Add note to text Tool for highlighting a section

to be changed to bold or italic.

4. Add sticky note Tool for making notes at

specific points in the text.

Highlights text in yellow and opens up a text

box where comments can be entered.

How to use it

Marks a point in the proof where a comment

needs to be highlighted.

How to use it

Highlight the relevant section of text.

Click on the Add note to text icon in the

Annotations section.

Click on the Add sticky note icon in the

Annotations section.

Type instruction on what should be changed

regarding the text into the yellow box that

appears.

Click at the point in the proof where the comment

should be inserted.

Type the comment into the yellow box that

appears.

USING e-ANNOTATION TOOLS FOR ELECTRONIC PROOF CORRECTION

5. Attach File Tool for inserting large amounts of

text or replacement figures.

Inserts an icon linking to the attached file in the

appropriate place in the text.

6. Drawing Markups Tools for drawing

shapes, lines and freeform annotations on

proofs and commenting on these marks.

Allows shapes, lines and freeform annotations to be

drawn on proofs and for comment to be made on

these marks.

How to use it

Click on the Attach File icon in the Annotations

section.

Click on the proof to where youd like the attached

file to be linked.

Select the file to be attached from your computer

or network.

Select the colour and type of icon that will appear

in the proof. Click OK.

How to use it

" Click on one of the shapes in the Drawing Markups

section.

" Click on the proof at the relevant point and draw the

selected shape with the cursor.

" To add a comment to the drawn shape, move the

cursor over the shape until an arrowhead appears.

" Double click on the shape and type any text in the

red box that appears.

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Prasugrel in percutaneous coronary intervention (PIPCI): a single

centre study

2 Matthew Van Wees, Alice Lam, Iouri Banakh

Frankston Hospital, Peninsula Health, Frankston, Australia

No. of pages: 7

CE: Saravanan S

Dispatch: 10.5.16

Background: Prasugrel is a potent antiplatelet agent for use in percutaneous coronary interventions, but it carries a signicant risk

of adverse events.

Aims: The aims of this study were to review the use of prasugrel in a population requiring treatment for acute coronary syndrome

(ACS), review adherence to guidelines, and assess the adverse event (AE) rates associated with its use.

Method: This study was a retrospective single-centre case series conducted at a metropolitan hospital in Victoria, Australia. All

patients who were admitted for treatment intervention for ACS and initiated on prasugrel between July 2011 and April 2013 were

included. The primary outcome was the adherence to international cardiac guidelines and subsidy restrictions. Secondary outcomes

included adherence to guidelines for prasugrel and heparin dosing, rates of concomitant use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, rates

of AEs and the severity of these according to TRITON-TIMI criteria. Chi-squared testing was conducted using SPSS 19.

Results: Prasugrel was initiated in 79 patients during the study period. Of these patients, 87% were deemed high risk for further

cardiovascular events and the use of prasugrel adhered to international guidelines. Over 10% of patients were started on prasugrel

despite being assessed as high risk for bleeding, with haemorrhages occurring in 29.1% of patients. A signicant proportion of

patients had prasugrel dosing outside the guideline recommendations in relations to age and weight.

Conclusions: The majority of patients initiated on prasugrel conformed to international and national guidelines; however, a high

bleeding rate was observed, which may warrant reviews with larger studies.

PE: Nagappan

Abstract

Address for correspondence: Iouri Banakh, Pharmacy Department, Frankston Hospital, 2 Hastings Road, Victoria 3199, Australia

E-mail: ibanakh@phcn.vic.gov.au

2016 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

METHODS

Prasugrel in percutaneous coronary intervention (PIPCI)

was a retrospective, single-centre case series study.

Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research (2016)

doi: 10.1002/jppr.1225

1225

Prasugrel is a potent and irreversible inhibitor of platelet

aggregation via binding to P2Y12 receptors and is indicated for management of coronary artery disease with

percutaneous intervention.1 Compared to other drugs of

the same class, based on clinical trials, prasugrel is associated with higher rates of bleeding, especially when given

to patients with histories of a previous cerebrovascular

accidents (CVA), transient ischaemic attacks (TIA) or cerebral haemorrhages.13 Prasugrel is therefore reserved for

patients at high risk of cardiovascular events with low

haemorrhagic predisposition as recommended by the current guidelines.4 Clinical trials identied that high-risk

patients such as those with histories of diabetes mellitus

beneted most from prasugrel treatment when compared

with the previous standard P2Y12 inhibitor clopidogrel.57

Notwithstanding the bleeding risks, prasugrel has been

approved by the Australian federal government, via the

Pharmaceutical Benets Scheme (PBS) for patients who

have received a percutaneous coronary artery angioplasty

without restriction criteria for other comorbidities.8

Prasugrels haemorrhagic complications that concern

clinicians usually involve, but are not limited to, gastrointestinal bleeding (haematemesis or malena), haematoma formation, complications arising from sheath

removal after the procedure and intracranial haemorrhage.1 Given its potency and high risk for adverse

events (AE)s, a review was carried out on prasugrel use

for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) management at a

single percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) centre

in Victoria, Australia.

Manuscript No.

INTRODUCTION

J P P R

Keywords: prasugrel, percutaneous coronary intervention, acute coronary syndrome, haemorrhage, safety, treatment.

Journal Code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

Patients included into the study were admitted for management of ACS with PCI and prasugrel initiation by

the primary interventional cardiologists at our hospital

between July 2011 and April 2013. The only exclusion

criterion for this study was preadmission prasugrel use.

Patients were identied and data was collected using

pharmacy dispensing and angiography records if they

had prasugrel initiated while undergoing a coronary

intervention. Discharge prescriptions were also reviewed

by a pharmacist, providing further opportunities to conrm initiation of prasugrel post-angiography rather than

continuing supply from preadmission.

Data Collection

Patients histories were audited via review of digitised

and/or paper copies of medical records stored at the

institutions Health Information Services. Data collected

included:

demographics,

patients

comorbidities,

patients weights, all inpatient haemorrhagic events and

complications, prasugrel dosing for loading and maintenance, use of anticoagulants and other antiplatelet

agents peri-procedurally and at discharge.

Ethics

Prasugrel in percutaneous coronary intervention study

received Human Research Ethics Committee exemption

as the study had no direct patient contact and due to

the audit nature of the study.

End-Points

The primary endpoints for this study were adherence to

current international and national guidelines for prasugrel prescribing for high-risk patients as well as adherence to the PBS subsidisation restrictions.8 The 2013

American College of Chest Physicians/American Heart

Association (ACCP/AHA) guideline for the management

of ST-elevation myocardial infarction4 and the 2012

European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of myocardial infarction presenting with STsegment elevation7 clearly dene prasugrels place in

therapy as an alternative to clopidogrel for high-risk

patients, including: clopidogrel-naive patients without

haemorrhagic risk factors, specically those without a

history of previous CVA/TIA, weighing more than 60 kg

and aged below 75 years, with larger myocardial

infarcts or with diabetes mellitus. In order for prescribing to be considered as adhering to the guidelines, highrisk patients were dened as those with pre-existing

major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), such as

Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research (2016)

M. Van Wees et al.

acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or stenosis or occlusion of a stent, history of diabetes mellitus or at

increased risk of in-stent thrombosis. Additional risk factors for stent thrombosis such as current smoker status,

diabetes mellitus and previous stent thrombosis were

also recorded.9

To conrm applicability for prasugrel therapy,

patients were conrmed not to have any contraindications to prasugrel treatment as specied in the product

information and treatment guidelines.

To successfully have met PBS approval criteria for

prasugrel subsidisation of both the 10 mg and the 5 mg

strengths, patients were required to have undergone a

PCI for the treatment of ACS, with concurrent aspirin

therapy.8

Safety End-Points

Due to prasugrels haemorrhagic AE prole, a maintenance dose reduction from 10 to 5 mg in patients aged

over 75 years of age or with weight less than 60 kg is

recommended in both the product information and

treatment guidelines.1,4,7 The criteria to determine if a

bleeding AE occurred was adopted from the prasugrel

registration trial, TRITON-TIMI 38.10 There were three

different classications of bleeding: major, minor and

minimal. Major bleeding was dened as an intracranial

haemorrhage, clinically overt bleeding with or without

imaging evidence or a haemoglobin drop of more than

5 g/dL. Additionally, a major bleed had to also meet

any one of the following criteria: hypotension requiring

inotropic support, requiring surgical intervention for

ongoing bleeding, necessitating a transfusion of four or

more units of blood (whole blood or packed red blood

cells) over a 48-h period, or a symptomatic intracranial

haemorrhage. A minor bleed was dened as clinically

overt bleeding with or without imaging evidence and

haemoglobin drop of between 3 and 5 g/dL, while a

minimal bleed was dened as clinically overt bleeding

with or without imaging evidence with a haemoglobin

drop less than 3 g/dL.

Heparin dosing was reviewed to check for adherence

to the guidelines, due to contribution to haemorrhagic

adverse events, with recommended doses of 50

70 units/kg (up to a maximum of 7000 units) when used

with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor or 60100 units/kg

(up to a maximum of 10 000 units) when used without

a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor.4

Additional analysis was conducted to compare the

single-centre population and AE rates to that of TRITON-TIMI 38 for safety and population selection purposes.

2016 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

Prasugrel in percutaneous coronary intervention

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

Statistics

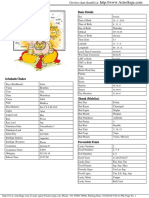

Table 1 Patient characteristics

An odds ratio was calculated and v2 test was used to

evaluate the signicance of haemorrhagic outcomes

between populations. SPSS 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA) was used for statistical analyses.

Demographics

RESULTS

Over the study period there were 79 patients who met the

inclusion criteria. The median age was 60 years and 75%

of patients were male. Common comorbidities among the

study population included hypertension (53%), hyperlipidaemia (58%) as well as other high risk factors, such as

smoking (35.5%), MACE (21.5%) and diabetes mellitus

(22.8%). See Table 1 for patient characteristics. At least

one risk factor for stent thrombosis was identied in more

than 40% of all patients, with over 20% of patients carrying more than two risk factors (refer to Table 2).

As part of ACS treatment, the majority of the patients

received bare-metal stents during their PCI, 37.9% of

patients received drug-eluting stents, and 11% had more

than one stent inserted. ACS management included glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (primarily abciximab) administration in addition to heparin-based anticoagulation in

nearly 25% of the study population. Approximately 95%

of patients received heparin during PCI, but only 20%

had dosage adjustment for their weight as recommended by treatment guidelines. Appropriateness of

heparin dosing could not be determined for 10% of

patients as there were no weights recorded in their medical notes or angiography records.

The majority of patients met the primary end-point of

adherence to the treatment guidelines for prasugrel use,

as well as PBS subsidy restriction. All but one patient

received concurrent prasugrel and aspirin therapies

post-PCI. The patient who did not undergo a PCI when

prasugrel treatment was initiated had the procedure

1 week prior.

While prescribing for the majority of patients adhered

to the treatment guidelines, haemorrhagic AEs were

reached by 29.1% of all patients. Most of these AEs were

mild, with 21% of the bleeding events not requiring

alteration to therapy. Patients who did require treatment

changes had: prasugrel treatment stopped as the bleeding risk was deemed too high (n = 3); addition of other

medications to manage bleeding, including proton pump

inhibitors to control gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 2); or

blood transfusions (n = 1). Three patients were readmitted to hospital to manage haematomas as a bleeding

complication. Only 8.7% of bleeding events were considered minor bleeds, with the remaining 91.3% being

2016 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

Median age (IQR)

Weight (average, kg)

Gender

Male (%)

Female (%)

Smoking status

Never smoked (%)

Ex-smoker (%)

Currently smoking (%)

Diabetes

No (%)

Yes (%)

Hypertension (%)

Hyperlipidaemia (%)

Previous MI/PCI/CABG (%)

Patients with prior CVA (%)

Type of stent

BMS (%)

DES (%)

Not documented (%)

Use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa

inhibitor

Received abciximab (%)

Received tiroban (%)

Taking warfarin (%)

Using aspirin concurrently (%)

Underwent PCI (%)

Number of stents inserted

1 (%)

2 or more (%)

Heparin use

Received heparin (%)

Correct dose (%)

Not assessable (%)

PIPCI

TRITON-TIMI 38

60 (53, 67)

82.8

61 (53,69)

NA

74.7

25.3

75

25

32.9

31.6

35.5

NA

NA

38

77.2

22.8

53

58

21.5

1.26

77

23

64

56

18

0

56.9

37.9

5.2

24

48

52

0

54

23

1

7.6

98.7

98.7

NA

NA

0

NA

99

89

11

NA

NA

94.9

20.2

10.1

66

NA

NA

BMS = bare metal stent; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft;

CVA = cerebrovascular accident (including haemorrhagic or

ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack); DES = drug eluting

stent; IQR = interquartile range; MI = myocardial infarction;

PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 2 Number of risk factorsa

Number of risk factors

Number of patients (%)

0

1

2

3 or more

14

33

19

13

(17.7)

(41.8)

(24)

(16.5)

Risk factors considered included presence of diabetes, age over

65 years, prior myocardial infarction/coronary artery bypass

graft/percutaneous coronary intervention, previous stent thrombosis and combinations of at least two of the following factors:

active smoking, hyperlipidaemia and/or hypertension.23

Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research (2016)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

M. Van Wees et al.

classied as minimal bleeding events. No major bleeding

events were identied during the study period.

3 Anticoagulation in addition to DAPT following PCI is

a haemorrhagic risk and 6.3% of our population

received triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin and prasugrel. The bleeding AE rate among patients on dual

antiplatelet therapy of prasugrel with aspirin was 22.7%

(18/73), while in patients on triple therapy including

warfarin, the bleeding rate was 83% (5/6) with an odds

ratio of 15.3, 95% CI 1.67139.5 (p = 0.0157). In the subgroup analysis of bleeding rates, 50% of patients over

75 years of age or under 60 kg suffered a haemorrhagic

event compared to 23% of those patients less than

75 years of age and over 60 kg.

As part of a safety audit it was identied that 88.6% of

patients received prasugrel loading prior to PCI, with the

remainder being loaded with clopidogrel. Over 75% of

patients received a standard daily maintenance dose of

10 mg, with the remainder either receiving the appropriately adjusted dose of 5 mg or maintenance dose that is

not aligned with the current recommendations. Prasugrel

dosing is described in Table 3. A signicant proportion

of patients (8.8%) did not receive the recommended dose

reductions to 5 mg, and one patient was treated with

prasugrel despite a recorded contraindication of prior

CVA. It was also identied that two patients had their

dose adjusted to 5 mg after PCI with no documentation

for the reason behind the adjustment.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the majority of prasugrel

prescribed at our institution is in-line with the current

Table 3 Prasugrel dosing

Prasugrel dose outcomes

Received prasugrel 60 mg load

Incorrect loading dosea

Received prasugrel 10 mg maintenance

Dose reductions

Over 75 years old, not reduced to 5 mg daily

Under 60 kg, not reduced to 5 mg daily

Wrong dose adjustment under 75 years old

Prasugrel used after CVA

Number of

patients (%)

70 (88.6)

9 (11.4)

62 (78.5)

3

4

2

1

(3.8)

(5)

(2.5)

(1.3)

CVA = cerebrovascular accident (incl. haemorrhagic or ischaemic

stroke, transient ischaemic attack).

a

Incorrect loading dose included loading twice with prasugrel,

loading with both prasugrel and clopidogrel, omitting a loading

dose of prasugrel.

Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research (2016)

national and international guidelines, and there was also

a high level of adherence to the PBS restrictions. During

the study period only one patient did not qualify for

subsidy as the patient required warfarin therapy on initiation of prasugrel, with aspirin cessation. However,

this patient on dual therapy with warfarin developed a

haematoma approximately 1 month later, necessitating

the cessation of prasugrel and the use of aspirin as the

alternative antiplatelet treatment. The recorded AEs

from this study showed that 29% of patients had haemorrhages with 9% of these being minor bleeds and the

remaining 91% as minimal bleeds. Three patients

required readmission for haematoma formation following initiation of prasugrel. No major or fatal bleeds

occurred during the study period. In other aspects, the

PIPCI study population was representative and comparable to that of the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial population for

median age 60 versus 61, female gender 25.3% versus

25%, diabetes 22.8% versus 23% and smoking history

35.5% versus 38%, respectively. The one difference of

importance between the study populations is that fewer

patients were treated at our institution with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, which may be reective of local

guidelines, greater use of other anticoagulants in TRITON-TIMI 38 such as bivalirudin and low molecular

weight heparins or perhaps lower-risk patients (Table 4). 4

As in TRITON-TIMI 38, safety has emerged as a signicant issue, with a dose reduction from 10 mg maintenance to 5 mg in patients aged over 75 years of age or

weight less than 60 kg recommended in the product

information based on pharmacokinetic data only at the

time of this study. Recently, evidence from the TRILOGY

ACS trial conrmed that a dose reduction is appropriate

in these patient groups.11 PIPCI subgroup analysis of 5

bleeding rates indicated that patients at higher risk of

haemorrhagic AEs from prasugrel had a 50% AE rate,

while the lower-risk group of patients, younger than

75 years of age and over 60 kg, had a 23% AE rate.

These results for haemorrhagic AEs are higher than that

Table 4 Adverse events

Adverse event

Number of patients (%)

Haematemesis

Haematoma

Ooze/bleed from wound site

Patients who had alterations to

therapy due to above bleedinga

3

13

7

5

(3.8)

(16.5)

(8.9)

(6.3)

a

Alterations to therapy include cessation of the drug, addition

of another medication (e.g. proton pump inhibitor) to control

bleeding.

2016 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

Prasugrel in percutaneous coronary intervention

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

reported from the registration trial, where the high-risk

subgroup had a 9.7% rate of minimal bleeds, and the

lower-risk group had an 8.3% rate of bleeding.11 Given

the evidence specifying the need for dose adjustment in

such populations and the contraindications for patients

with histories of CVA/TIA, it was identied that 12.6%

of patients either received a dose of prasugrel that did

not meet the recommendations or received prasugrel

when deemed inappropriate according to the prescribing information and harmful by ACCP/AHA guidelines.4 In this case series only one patient was prescribed

prasugrel with a history of CVA, which is lower than

the results of a larger audit of prasugrel usage, where

13.9% of patients received prasugrel despite a history of

CVA.12 In a separate audit of prasugrel use, between 6

and 10% of patients were inappropriately initiated and

discharged on the P2Y12 inhibitor.13

Beyond the maintenance dose adjustments, the decision on whether or not to load a patient with a second

antiplatelet agent when switching between agents is an

area of uncertainty. The PIPCI population had 10% of

patients either loaded with both clopidogrel and prasugrel, with no clear documentation for the duplication, or

received no loading dose of the second agent but a

switch of P2Y12 inhibitor for maintenance therapy. One

patient was loaded twice with prasugrel despite a

recorded AE of haematemesis. Recent pharmacokinetic

studies indicate that when swapping from clopidogrel

to prasugrel after a 600 mg clopidogrel loading dose,

30 mg of prasugrel is sufcient to suppress platelet reactivity to a similar level of a 60 mg prasugrel loading

dose.14 This antiplatelet loading strategy was not followed during our study period and may have contributed to AE development. However, there is currently

a lack of prospective data regarding the clinical efcacy

of this approach.

In addition to uncertainty in antiplatelet loading

strategies, triple therapy with inclusion of anticoagulant

has emerged as an important safety issue. Despite the

small numbers included in our study, which is lower

compared to 15.4% in other reviews,12 the results indicate that there is a signicant increase in bleeding rates

among patients using warfarin with prasugrel; hence

there is a need to determine if the combination of warfarin and prasugrel has a place in therapy. Patients who

required warfarin were excluded from the TRITONTIMI 38 trial.10 As age is a major risk factor for atrial

brillation and ACS, the need for combination therapy

and the challenge of balancing risk of thrombosis versus

the risk of bleeding will rise with the aging population.

The WOEST trial compared triple therapy (aspirin,

clopidogrel and warfarin) to dual therapy (clopidogrel

and warfarin) in patients post-stent insertion.15 This

2016 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

study found lower bleeding rates in the dual therapy

group compared to triple therapy and it identied that

patients treated with dual therapy alone had lower allcause mortality; however, this study was not powered

to detect these differences. In another prospective study

of triple therapy with prasugrel or clopidogrel, the prasugrel arm had signicantly higher rates of minor or

major bleeding (adjusted hazards ratio: 3.2, 95% CI: 1.1

9.1) with no therapeutic benet.16 There have also been

case reports of fatal bleeding associated with prasugrel

triple therapy.17 More recent studies have identied that

triple therapy, especially among the elderly, as a major

clinical issue18 due to haemorrhagic AE and our study

adds to the data.

Additionally, data regarding the co-administration of

prasugrel with the new oral anticoagulants such as dabigatran and the factor Xa inhibitors are required, given

the increasing utilisation of these medications with

improved safety prole relative to warfarin in atrial a

brillation population. The addition of rivaroxaban to

aspirin following non-ST-segment elevation myocardial

infarction has survival benets and evidence shows lowdose rivaroxaban has survival benets in ACS patients

as demonstrated in the ATLAS ACS-2 TIMI-51 study.19

Prasugrel on the other hand is more likely to be harmful

as indicated by the more recent TRANSLATE-ACS

study with prasugrel triple therapy compared to clopidogrel triple therapy in ACS and atrial brillation

patients.20

Another safety signal identied during the PIPCI

study is that only 20% of patients had their heparin

dosage adjusted for body weight and glycoprotein IIb/

IIIa inhibitor use. This potentially could have contributed to the increase in bleeding rates for minimal

bleeds when compared to TRITON-TIMI 38. Activated

clotting time (ACT) was not recorded, due to the poor

correlation between ACT and bleeding.21 Previous studies have shown that the dosing of heparin is often above

that recommended in guidelines prior to PCI and is a

potential target for further quality improvement initiatives.22 However, due to the study design, no analysis

on heparin dosing and bleeding rates was done.

This study indicates that the Australian experience

with prasugrel may mirror that seen internationally,

warranting further investigation at other institutions that

have prasugrel available on their formulary for ACS

management. However, this study was limited by the

small number of patients included in the study despite

the period covered. Furthermore, there is a lack of

power for statistical analysis to be applied to the results.

This study was also limited by the incomplete recording

in patients histories as evident by missing data. Therefore, the study ndings need to be conrmed with

Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research (2016)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

larger studies and until then can only be considered as

hypothesis raising of safety issues identied.

CONCLUSION

Prasugrel was prescribed in accordance with national

and international guidelines, as well as PBS restrictions

for the majority of patients during the study period. Prasugrel loading dose approaches when switching

between antiplatelet agents was identied as a practice

issue in the study. The safety prole of prasugrel was

also identied to be signicantly different to that quoted

in the trial data used to gain approval for the medication in terms of minimal bleeding. However, as the

study was limited by size and period, further audits of

prasugrel use at PCI-capable centres is warranted before

considering changes to clinical practice.

Competing Interests

None declared.

REFERENCES

1 Therapeutic Goods Administration [Internet]. Product and

Consumer Medicine Information. Prasugrel product information,

[Modied 2013 Sep 27; Cited 2015 May 2]. Available from

<www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?

OpenAgent&id=CP-2010-PI-011843.>

2 AMH Online [Internet]. Adelaide, SA: AMH Pty Ltd; 2013.

Prasugrel [Modied 2013 July; Cited 2015 Feb 2]; [Approx 2

screens]. Available from <www.amh.net.au/online/

view.php?page=chapter7/monographprasugrel.html#prasugrel.>

3 Biondi-Zoccai G, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, Abbate A, Romagnoli

E, Sangiorgi G, et al. Adjusted indirect comparison meta analysis

of prasugrel versus ticagrelor for patients with acute coronary

syndromes. Int J Cardiol 2011; 150: 32531.

4 OGara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA

guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial

infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology

Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice

Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 127: e362.

5 Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo

W, Gottlieb S, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with

acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 200115.

6 Cayla G, Silvain J, OConnor SA, Collet JP, Montalescot G. An

evidence-based review of current anti-platelet options for STEMI

patients. Int J Cardiol 2013; 166: 294303.

7 Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute

myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology

(ESC), Steg PG, James SK, et al. ESC Guidelines for the

management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting

with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569619.

Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research (2016)

M. Van Wees et al.

8 Pharmaceutical Benets Scheme [Internet]. Canberra, ACT:

Department of Health; 2013. Pharmaceutical Benets SchemePRASUGREL. [Cited 2015 Feb 2]; [1 Screen]. Available from

<www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/9496T.>

9 Sudhir K, Hermiller JB, Ferguson JM, Simonton CA. Risk factors

for coronary drug-eluting stent thrombosis: inuence of

procedural, patient, lesion, and stent related factors and dual

antiplatelet therapy. ISRN Cardiol 2013; 2013: 748736.

10 Wiviott SD, Antman EM, Gibson CM, Montalescot G, Riesmeyer J,

Weerakkody G, et al. Evaluation of prasugrel compared with

clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: design

and rationale for the Trial to assess Improvement in Therapeutic

Outcomes by optimizing platelet InhibitioN with prasugrel

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38 (TRITON-TIMI 38). Am

Heart J 2006; 152: 62735.

11 Roe MT, Goodman SG, Ohman EM, Stevens SR, Hochman JS,

Gottlieb S, et al. Elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes

managed without revascularization: insights into the safety of

long-term dual antiplatelet therapy with reduced-dose prasugrel

versus standard-dose clopidogrel. Circulation 2013; 128: 82333.

12 Hira RS, Kennedy K, Jneid H, Alam M, Basra SS, Petersen LA,

et al. Frequency and practice-level variation in inappropriate and

nonrecommended prasugrel prescribing: insights from the NCDR

PINNACLE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63(Pt A): 28767.

13 Sandhu A, Seth M, Dixon S, Share D, Wohns D, Lalonde T, et al.

Contemporary use of prasugrel in clinical practice: insights from

the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular

Consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013; 6: 2938.

14 Diodati JG, Saucedo JF, French JK, Fung AY, Cardillo TE,

Henneges C, et al. Effect on platelet reactivity from a prasugrel

loading dose after a clopidogrel loading dose compared with a

prasugrel loading dose alone: Transferring From Clopidogrel

Loading Dose to Prasugrel Loading Dose in Acute Coronary

Syndrome Patients (TRIPLET): a randomized controlled trial. Circ

Cardiovasc Interv 2013; 6: 56774.

15 Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, Kelder JC, De Smet BJ,

Herrman JP, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in

patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing

percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised,

controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 110715.

16 Sarafoff N, Martischnig A, Wealer J, Mayer K, Mehilli J, Sibbing

D, et al. Triple therapy with aspirin, prasugrel, and vitamin K

antagonists in patients with drug-eluting stent implantation and

an indication for oral anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:

20606.

17 Savonitto S, Ferri M, Corrada E. Fatal bleedings with prasugrel as

part of triple antithrombotic therapy. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed)

2014; 67: 2256.

18 Otsuki H, Yamaguchi J, Arashi H, et al. Safety and efcacy of antithrombotic therapy after PCI in octogenarians with atrial

brillation: A multicenter study. American Heart Association

(AHA) 2015 Scientic Sessions. 2015; Orlando, FL. Abstract 4312.

19 Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Bassand JP, Bhatt DL, Bode C,

et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary

syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 919.

20 Jackson LR, Ju C, Zettler M, Messenger JC, Cohen DJ, Stone GW,

et al. Outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction

undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention receiving an oral

anticoagulant and dual antiplatelet therapy: a comparison of

2016 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

Prasugrel in percutaneous coronary intervention

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

clopidogrel versus prasugrel from the TRANSLATE-ACS Study.

JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015; 8: 18809.

21 Soleimannejad M, Aslanabadi N, Sohrabi B, Shamshirgaran M,

Separham A, Kazemi B, et al. Activated clotting time level with

weight based heparin dosing during percutaneous coronary

intervention and its determinant factors. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res

2014; 6: 97100.

22 Wang TY, Magid DJ, Ting HH, Li S, Alexander KP, Roe MT, et al.

The quality of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medication

administration among ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

patients transferred for primary percutaneous coronary

intervention. Am Heart J 2014; 167: 8339.

2016 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia

23 Chew DP, Aroney CN, Aylward PE, Kelly AM, White HD,

Tideman PA, et al. 2011 Addendum to the National Heart

Foundation of Australia/Cardiac Society of Australia and New

Zealand Guidelines for the management of acute coronary

syndromes (ACS) 2006. Heart Lung Circ 2011; 20: 487502.

Received: 28 October 2015

Revised version received: 12 April 2016

Accepted: 13 April 2016

Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research (2016)

Author Query Form

Journal:

JPPR

Article:

1225

Dear Author,

During the copy-editing of your paper, the following queries arose. Please respond to these by marking

up your proofs with the necessary changes/additions. Please write your answers on the query sheet if

there is insufcient space on the page proofs. Please write clearly and follow the conventions shown on

the attached corrections sheet. If returning the proof by fax do not write too close to the paper's edge.

Please remember that illegible mark-ups may delay publication.

Many thanks for your assistance.

Query reference

Query

AUTHOR: Running title should not exceed a maximum of 40 characters.

Please check and provide a suitable short title to conform to the journal

style.

AUTHOR: Please conrm that given names (red) and surnames/family

names (green) have been identied correctly.

AUTHOR: Please spell out DAPT

AUTHOR: Table 4 was not cited in the text. An attempt has been made

to insert the table into a relevant point in the text - please check that this

is OK. If not, please provide clear guidance on where it should be cited

in the text.

AUTHOR: To facilitate sequential numbering, reference numbers have

been reordered. Please check.

AUTHOR: If there are fewer than 7 authors for all et al. References,

please supply all of their names. If there are 7 or more authors, please

supply the rst 6 author names then et al. Please check and update all

such references found in the list.

AUTHOR: Please check and conrm the history details.

Remarks

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Katralum Karpithalum Youtube Links - 17.2.21Dokument8 SeitenKatralum Karpithalum Youtube Links - 17.2.21Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- TNEBDokument4 SeitenTNEBDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dokument1 SeiteScientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- VarmakalaiDokument16 SeitenVarmakalaikowsilaxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reimbursement FormDokument6 SeitenReimbursement FormDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dokument1 SeiteScientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dokument1 SeiteScientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dokument1 SeiteScientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dokument1 SeiteScientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dokument1 SeiteScientific Publishing Services (P) LTD.: Pay Slip For The Month of December 2019Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Netwrix Change Notifier For Active Directory Quick-Start GuideDokument19 SeitenNetwrix Change Notifier For Active Directory Quick-Start GuideDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Netwrix Change Notifier For VMware Quick-Start GuideDokument13 SeitenNetwrix Change Notifier For VMware Quick-Start GuideDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- VedicReport3 10 20169 50 22PMDokument47 SeitenVedicReport3 10 20169 50 22PMDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timetable Slips Si 2016 - WebsiteDokument3 SeitenTimetable Slips Si 2016 - WebsiteDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Varma Sikichai for All DiseasesDokument38 SeitenVarma Sikichai for All DiseasesDinesh Kumar67% (15)

- r1 JPPR 1228 ReviewDokument8 Seitenr1 JPPR 1228 ReviewDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timetable Slips Term 3 2016 - WebsiteDokument4 SeitenTimetable Slips Term 3 2016 - WebsiteDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Furniture1 Layout ModelDokument1 SeiteFurniture1 Layout ModelDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- OnlineecDokument2 SeitenOnlineecDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- VedicReport3 10 20169 50 22PMDokument47 SeitenVedicReport3 10 20169 50 22PMDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading the Lotus Sūtra for Spiritual InsightDokument150 SeitenReading the Lotus Sūtra for Spiritual InsightDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indersons: S. NO. Category Unit Rate Rs. 5400 /-Rs. 4000 / - Rs. 160 / - Rs. 125 / - Rs. 75 / - Rs. 75 / - Rs. 15Dokument1 SeiteIndersons: S. NO. Category Unit Rate Rs. 5400 /-Rs. 4000 / - Rs. 160 / - Rs. 125 / - Rs. 75 / - Rs. 75 / - Rs. 15Dinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lotus SutraDokument370 SeitenLotus SutraYen Nguyen100% (3)

- r1 DMCN 13172 ReviewDokument5 Seitenr1 DMCN 13172 ReviewDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data ONTAP 7-Mode Administration. StudentGuide PDFDokument840 SeitenData ONTAP 7-Mode Administration. StudentGuide PDFNitin Kanojia100% (1)

- r1 JPPR 1226 ReviewDokument6 Seitenr1 JPPR 1226 ReviewDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- FirstSteps2ndEdition LongDokument172 SeitenFirstSteps2ndEdition LongDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- r1 DMCN 13163 ReviewDokument12 Seitenr1 DMCN 13163 ReviewDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- r1 DMCN 13172 ReviewDokument5 Seitenr1 DMCN 13172 ReviewDinesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- FormularyDokument29 SeitenFormularykgnmatinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handin 1 - Cialis PPT PresentationDokument14 SeitenHandin 1 - Cialis PPT PresentationMia_NaterNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study of Over The Counter Medication Use, Among Patients Presenting To Family Physicians, at A Teaching Hospital in KarachiDokument12 SeitenA Study of Over The Counter Medication Use, Among Patients Presenting To Family Physicians, at A Teaching Hospital in KarachiSamruddhi ZambareNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Black CandleDokument178 SeitenThe Black CandleJordan ChampagneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name of Drug Action Indication Contraindication Adverse Reaction Nursing ConsiderationDokument4 SeitenName of Drug Action Indication Contraindication Adverse Reaction Nursing ConsiderationClariss AlotaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Toxicology Guide to Poison ManagementDokument79 SeitenClinical Toxicology Guide to Poison ManagementSaddam HossainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adderall Research PaperDokument6 SeitenAdderall Research Paperapi-316769369100% (3)

- MedicineDokument3 SeitenMedicineIntanNurjannahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dysmenorrhea Definition PDFDokument14 SeitenDysmenorrhea Definition PDFYogi HermawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drugs Affecting the Gastrointestinal SystemDokument5 SeitenDrugs Affecting the Gastrointestinal SystemPaul André AzcunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opioid Conversion GuideDokument3 SeitenOpioid Conversion Guidesen ANoch keine Bewertungen

- Beatles - White Album (Score)Dokument4 SeitenBeatles - White Album (Score)LeeEstradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhu CMNC CasestudyreportDokument5 SeitenDhu CMNC Casestudyreportapi-300133703Noch keine Bewertungen

- Amlodipine ReadingDokument12 SeitenAmlodipine Readingines pachecoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharma Domain 101 - The Industry Lingo (Latest)Dokument10 SeitenPharma Domain 101 - The Industry Lingo (Latest)Ankit AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Herbs - Medicinal Herb FAQDokument188 SeitenHerbs - Medicinal Herb FAQCorinnaAwakeningNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analgesic & Anesthetic: Dr. Yunita Sari Pane, MsiDokument92 SeitenAnalgesic & Anesthetic: Dr. Yunita Sari Pane, Msiqori fadillahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physician Fax Order FormDokument1 SeitePhysician Fax Order FormAnnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- L. Thyme+HennaDokument19 SeitenL. Thyme+HennaPăduraru NataliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beg Talk To Doctor - Unit 1Dokument66 SeitenBeg Talk To Doctor - Unit 1Eliza Cristea OneciNoch keine Bewertungen

- IV Therapy: Saline Solution for IVDokument6 SeitenIV Therapy: Saline Solution for IVMatt Razal TabliganNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3911 Human EnUserGuide Neurobion 1.3.3.2 English LeafletDokument1 Seite3911 Human EnUserGuide Neurobion 1.3.3.2 English LeafletNadia AfifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 11Dokument5 SeitenChapter 11DEENoch keine Bewertungen

- Nasal and Pulmonary Drug Delivery SystemDokument71 SeitenNasal and Pulmonary Drug Delivery SystemDRx Sonali TareiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birth Control: Search For.Dokument4 SeitenBirth Control: Search For.sujingthetNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Registered Drugs As of August 2012: DR No Generic Name Brand Name Strength Form CompanyDokument75 SeitenList of Registered Drugs As of August 2012: DR No Generic Name Brand Name Strength Form CompanyBenjamin TantiansuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Medical Association challenges constitutionality of Generics ActDokument2 SeitenPhilippine Medical Association challenges constitutionality of Generics Actshel100% (1)

- 6.5 MCC Oxymetazoline SubmissionDokument20 Seiten6.5 MCC Oxymetazoline SubmissionAmit DwivediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buy MTP KIT Abortion Pills OnlineDokument6 SeitenBuy MTP KIT Abortion Pills OnlinebestgenericshopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semi Solids PDFDokument3 SeitenSemi Solids PDFAsif Hasan NiloyNoch keine Bewertungen