Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ajsms 4 2 63 70

Hochgeladen von

Iqbal Azis SOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ajsms 4 2 63 70

Hochgeladen von

Iqbal Azis SCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES

ISSN Print: 2156-1540, ISSN Online: 2151-1559, doi:10.5251/ajsms.2013.4.2.63.70

2013, ScienceHu, http://www.scihub.org/AJSMS

Teachers Promotion of Creativity in Basic Schools

Kingsley Nyarko, Wiafe Akenten and Inusah Abdul-Nasiru,

University of Ghana, Psychology Department, P. O. Box LG 84, Legon,

kingpong73@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

The study was conducted to find out the role of teachers in fostering creativity among basic

school students in Ghana. The sample was drawn on 172 teachers, with different teaching

qualifications and experience between the ages of 20 and 60 years. The findings show that

teachers at the basic level of education promote creativity among students through motivation,

divergent thinking, and the promotion of a conducive learning environment. Again, it was found

out that teachers view the promotion of creativity as a joint responsibility of parents and teachers.

Finally, although teachers agree that creativity is fostered through motivation, there was no

statistically significant difference between teachers who view creativity to be intrinsically

motivated and those who view it to be extrinsically motivated. The implications of the findings are

examined.

Keywords: Creativity, motivation, divergent thinking, environment, parents, teachers, basic

school students

INTRODUCTION

Natural selection, an aspect of the theory of evolution

(Darwin, 1859) suggests that the survival of living

species, especially human beings, to a large extent

depends on their ability to adapt to their environment.

Over the years, the ability of nations and societies to

live productively and meaningfully in their respective

environments has been made possible by the instinct

of survival. Survival in the world, especially in the

earlier centuries required individuals to devise means

to make them live efficiently and effectively in their

environments. Thus, those who survived in the earlier

centuries were those who might have been thinking

outside the box. This is because following the status

quo or being static in ones thoughts never brings

about change and progress. That was the reason

why Darwin indicated that those who are likely to

survive within any ecology are those individuals who

are fit; thus survival of the fittest (Darwin, 1859).

st

In the 21 century, as a result of globalization and

fierce competition among competitors and nations,

governments, educators, and other stakeholders

have been ferreting out ways, not only to survive, but

to make live more meaningful and productive

(Grainger & Barnes, 2006; United Nations, 2008).

The quest to improving the environment and the

living standards of the citizenry has led to civil society

questioning the relevance of current educational

practices. This is because some scholars and

educators hold the view that current educational

practices fail to prepare students to be original in their

thoughts, and thus prevent them from deviating from

the status quo or standard practice. They therefore

conclude that the classroom is not the ideal

environment to foster creativity; since in most cases it

stifles it (Robinson, 2009; Sarason, 1990; Sharan &

Chin Tan, 2008; Sternberg, 2006).

According to these scholars, this is due to the fact

that much of what pupils do in school is driven by a

mindset of a specific answer and one principal way to

arrive at it. Therefore, as children grow older, the less

they have the courage to try other ways of thinking

and the more they try to avoid being wrong.

Documented research in educational psychology

(Alexander, Murphy, & Woods, 1994; Dent, 1995;

Kauffman & Hamza, 1998; Pintrich, Marx, & Boyle,

1993; Postman, 1993; Torrance & Safter, 1990), in

addition to life experiences, workplace experiences,

and individual insights, revealed deficiencies in

educational teaching methods and strategies in which

creative thinking and problem solving are taught at all

educational levels.

As indicated previously, in a world dominated by

increasing technological advancements, creativity

has become an essential facet; human skills and

peoples powers of creativity and imagination are

principal resources in a knowledge driven economy

(Robinson, 2000). As we continue to observe and

Am. J. Soc. Mgmt. Sci., 2013,4(2): 63-70

experience changes in societies, the ability to live

with uncertainty and deal with convoluted issues in

our environments have become crucial and

organizations and governments are now more

concerned than ever to promote creativity (Grainger

& Barnes, 2006). Creativity is thus becoming a nonnegotiable subject in the transformation and

sustenance of progress in our societies.

also emphasized the value of a whole school

commitment to creative education. The more

teachers fathom the significance of creativity and its

relationship to learning and motivation, the better

equipped they are to enhance their students

creativity.

Although, there have been empirical studies on the

role of teachers in promoting creativity elsewhere in

the world (Tan, 1999; Fryer, 2003, 2008), there has

not been one conducted in the country. In their study

on creativity, Nyarko, Assumeng, and Atindanbila

(2012), examined the origin and understanding of

creativity among basic school teachers. The current

study will thus help educators and policy makers to

implement intervention programmes to enable our

schools to produce creative minds in the country. The

study is different from other prior studies because,

apart from finding out how teachers promote

creativity in schools, it also provides the views of

teachers regarding the place of parents and

motivation in the fostering of creativity in pupils.

The question to be asked after examining the

centrality of creativity in societies is how to nurture

creative exploits in pupils in the country? As a result

of the effect of nurture on child development, it is

believed that practices within the environment of

pupils have the faculty of instilling in them creative

potentials. In his ecological systems theory,

Bronfenbrenner (1979) underscores the impact of the

environment in influencing the behaviour of

individuals. Also Csikszentmihalyi (1996) has

emphasized the importance of the environment in

promoting creativity. Also, the Componential Theory

of Creativity assumes that all humans with normal

capacities are able to produce at least moderately

creative work in some domain, some of the time

and that the social environment (the work

environment) can influence both the level and the

frequency of creative behavior (Amabile, 1997,

p.42).

In line with the above reviewed studies, the

researchers sought to 1) find out how basic school

teachers in Ghana promote creativity among their

pupils, 2) determine whether teachers view the

fostering of creativity to be the preserve of only

teachers or parents or both, 3) ascertain whether

teachers see creativity to be intrinsically or

extrinsically motivated, and 4) ferret out if there will

be differences in the fostering of creativity between

teachers who view creativity to be intrinsically

motivated and those who view it to be extrinsically

motivated.

Thus processes and structures that are rolled out by

educational authorities and teachers have the

capacity of producing significant improvements on

their students. When teachers motivate their pupils,

provide opportunities for them to think divergently,

and also create for them an enabling environment for

them to engage in creative activities, they are more

likely to unearth the creative potentials in them.

Amabile (1999) suggested that a persons intrinsic

motivation is crucial to creativity. She argued that

extrinsic motivation such as money is much less

effective: Money doesnt necessarily stop people

from being creative, but in many situations, it doesnt

help (p. 6). According to (Amabile, 1997; Drazin et

al., 1999), people are most likely to be creative when

they love what they do and do what they love. Mestre

(2002) indicated that novice learners find it difficult to

engage in flexible thinking, thus it is necessary to

support their diverse thinking in our quest to fostering

their creative potentials.

Flowing from the above, it is hypothesized that 1)

teachers are likely to promote creativity through

motivation, the promotion of divergent thinking, and

creation of a conducive environment, 2) teachers are

more likely to view creativity as a joint responsibility

between teachers and parents than the preserve of

only teachers or parents, 3) teachers are more likely

to view creative pupils as intrinsically motivated than

extrinsically motivated, and 4) teachers who view

creative pupils to be intrinsically motivated are more

likely to promote it than those who view it to be

extrinsically motivated.

METHOD

Torrance (1995, 1965) has established in his studies

across cultures that creativity flourishes where it is

valued. Similarly, Fryer (1996) discovered that

teachers in the United Kingdom who were very eager

in promoting the creative potential of their students

Sample: The sample of the study was drawn on 172

teachers, consisting of 61 females (35.5%) and 111

males (64.5 %) who were randomly selected from

some basic education schools from the Ashanti- and

Greater Accra regions in Ghana. Their ages ranged

64

Am. J. Soc. Mgmt. Sci., 2013,4(2): 63-70

Promoters of creativity: The teachers were asked a

closed-ended question to find out elements in the

environment that foster creativity in children. The

question was, which of the following individuals

promote creativity in children? The available options

were, 1) teachers, 2) parents, and 3) both teachers

and parents. Teachers were coded as 1, parents

were coded as 2, and both teachers and parents

were coded as 3.

between 20 and 60 years and had taught between 3

and 40 years in basic schools. Again, 89 (51.7%)

teach in private schools, whereas 83 (48.3%) teach in

public schools. 42 (24.4 %) of the teachers have

senior high school education, 73 (42.4 %) training

college education, 44 ( 25.6%) university education,

and 13 (7.6%) with other educational qualifications.

Furthermore, 127 (73.8%) are professional teachers,

whereas 45 (26.2 %) are non-professional teachers.

Finally, 51 (29.7%) teach at the lower primary, 51

(29.7%) teach at the upper primary, and 70 (40.7%)

teach at the junior high school.

Motivation: In finding out from the teachers whether

creativity is intrinsically or extrinsically generated, a

close-ended question was asked. The question was,

is creativity intrinsically motivated or extrinsically

motivated? Intrinsic motivation was coded as 1,

whereas extrinsic motivation was coded as 2.

Procedure: The researchers started the data

gathering process by seeking the approval of the

head teachers of the participating schools. After the

head teachers had agreed to the request, the

teachers were informed about the objectives of the

study and the guarantee of their confidentiality.

Those who were convinced of the studys objectives,

and agreed to take part were randomly selected to

form the sample of the study. The questionnaires

were administered by research assistants, and

participants were given a week to complete them.

After the completion of the questionnaires by

participants, they were thanked for availing

themselves to be part of the study.

Teacher fostering of creativity scale (Nyarko et

al., 2012): The teacher fostering of creativity scale

developed by Nyarko et al. (2012) was used to

measure the teachers promotion of creativity in the

pupils. It is a 15- item scale with a 5 point response

format ranging from 1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly

agree. It measures how teachers reinforce creative

acts, encourage diverse opinions and thinking, and

provide a conducive learning atmosphere in the

classroom for the exhibition of creative acts. Some of

the items on the scale include, reward pupils`

unusual ideas through praises and other rewards,

assist pupils to examine issues from different

perspectives, and provide an atmosphere that

allows pupils to freely express their ideas, views, and

thoughts during discussion. The original scale has a

reliability of 0.87, and those of the subscales are:

reinforcement of creative acts 0.60; encouragement

of diverse thinking, 0.88; and provision of a

conducive learning environment, 0.80. The overall

reliability of the scale for the current study is 0.85,

and the subscales have the following reliabilities:

reinforcement of creative acts 0.55; encouragement

of diverse thinking, 0.85; and provision of a

conducive learning environment, 0.67.

Measures: The research design used for the study

was a survey which necessitated the use of a

questionnaire in collecting the data. This instrument

asked for specific information about the status of the

teachers such as their age, gender, qualification

status, level of completed education, level of class

they teach and the type of school they teach (i.e.

whether private or public). The main measures were

on their promotion of creativity, individuals who

promote creativity, and type of motivation that fosters

creativity.

Promotion of creativity: In finding out how the

teachers promote creativity among their pupils, an

open-ended question was asked. The question was,

how do you promote creativity among your pupils?

Some of the answers given by the participants are, I

promote creativity of my pupils through praises, I

promote the creativity of my pupils through rewards,

I promote the creativity of my pupils through

motivation, I promote the creativity of my pupils by

allowing them to express their views and opinions

freely, I promote the creativity of my pupils by

allowing them to engage in constructive debates, I

encourage them to look at issues from different

perspectives, I create an atmosphere devoid of fear

and intimidation in the classroom.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF DATA

In analyzing the data, descriptive and inferential

statistics were used. Descriptive statistics was used

to find out how teachers promote creativity, their view

on whether creative pupils are intrinsically or

extrinsically motivated, and whether teachers or

parents or both teachers and parents are the

promoters of creativity. Descriptive statistics was

utilized because it provides an understanding of the

data via their frequency distribution, mean, and

standard deviation.

65

Am. J. Soc. Mgmt. Sci., 2013,4(2): 63-70

Additionally, t-test was utilized to find out the

differences in the fostering of creativity by teachers

who view creativity to be intrinsically motivated and

those who view it to be extrinsically motivated. That is

whether teachers who view creativity to be

intrinsically motivated will foster creativity more than

those who view creativity to be motivated

extrinsically.

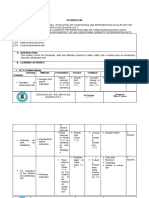

Frequency Valid Percent

teachers

4.10

parents

1.20

teachers and parents

163

94.80

Total

172

100.00

RESULTS

Teachers promotion of creativity: The table below

(table 1) shows how teachers foster creativity in their

pupils. The descriptive statistics show that 81 of the

teachers representing 47.1% use motivation in

promoting creativity among their pupils. 60 teachers,

representing 34.9% promote the creativity of their

pupils through the promotion of divergent thinking.

Finally, 31 of them, representing 18% promote

creativity in their pupils by creating a conducive

learning environment for them.

Table 1 Teachers promotion of creativity

Frequency

motivation

promotion

thinking

of

creation

of

environment

Total

Teachers view on whether creativity is

intrinsically or extrinsically motivated: From the

table below (table 3), it is evident that teachers differ

in relation to whether creative pupils are intrinsically

or extrinsically motivated. It shows that 96 of the

teachers, representing 55.8% are of the view that

creative children are intrinsically motivated, whereas

76 of them representing 44.2% view creative children

to be extrinsically motivated.

Percent

81

47.10

divergent

60

34.90

conducive

31

18.00

172

100.00

Table 3 Teachers view on whether creativity is

intrinsically or extrinsically motivated

Frequency

Percent

intrinsic motivation

96

55.80

extrinsic motivation

76

44.20

Total

172

100.00

Type of motivation as a determinant of teachers

fostering of creativity: The table below (table 4)

addresses the main hypothesis of the study which

states that teachers who view creativity to be

intrinsically motivated are more likely to promote

creativity among their pupils than teachers who view

creativity to be extrinsically motivated. The results

show that there is no significant difference in the

fostering of creativity between teachers who view

creative pupils to be intrinsically motivated (M=

63.31, SD= 6.04) and those who view creative pupils

to be extrinsically motivated (M= 63.15, SD= 5.23), t

(170) = .191, p>0.05.

Promoters of creativity: The table below (table 2)

reveals teachers views on individuals who promote

creativity. It shows that teachers are of the view that

the promotion of creativity is not only the preserve of

teachers. The descriptive statistics indicates that 163

of the teachers, representing 94.8% view the

promotion of creativity as a shared responsibility

between teachers and parents, whereas 7

representing 4.1% and 2, representing 1.2% of them

view the promotion of creativity to be the

responsibility of teachers and parents respectfully.

Table 2 Individuals who promote creativity in

pupils

Table 4 t-test of type of motivation as a determinant of teachers fostering of creativity

Type

of Frequency

Mean

Standard

Degree

of t-test

Motivation

deviation

freedom

Intrinsic

96

63.31

6.04

170

.191

motivation

Extrinsic

76

63.15

5.23

motivation

p> 0.05

66

significance

.85

Am. J. Soc. Mgmt. Sci., 2013,4(2): 63-70

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

enough to voice their opinions and explore new

ideas. In fact, every child has creative potentials that

can be expressed under certain favourable

conditions. One way to get students comfortable

enough to do this is for teachers to model creativity

and show their own interests. Hennessey (1997)

suggests teachers show students that you value

creativity, and that you not only allow it but also

actively engage in it.

The study was principally carried out to find out how

Ghanaian basic school teachers promote creativity

among their pupils. The first hypothesis was to figure

out the ways that teachers use to foster creativity in

their pupils. It was specifically stated that teachers

are more likely to promote the creativity of their

students through motivation, divergent thinking, and

the creation of a conducive learning environment.

The results show that the teachers foster creativity in

their students by motivating them, encouraging them

to engage in divergent thinking in their deliberations,

and providing them with a conducive learning

environment. This finding corroborates that of

Amabile (1999) that suggested that a persons

intrinsic motivation is crucial to creativity. She

bickered that extrinsic motivation such as money, is

much less effective: Money doesnt necessarily stop

people from being creative, but in many situations, it

doesnt help (p. 6). It is therefore very significant, in

fostering creativity in students, to build on their

natural interests, passions, and the value derived

from the things they do. According to (Amabile, 1997;

Drazin et al., 1999), people are most likely to be

creative when they love what they do and do what

they love. Intrinsic motivation is essential in fostering

creativity in people because it involves not only the

personal interests and personalities of individuals, but

also how interesting the tasks are, and the value

derives from them.

Furthermore, to promote creativity, it is very

necessary for teachers to foster divergent thinking in

the pupils. Again, to promote diverse and flexible

thinking, it is critical for learners to generate diverse

problems. In learning by problem posing, it is not

useful for learners to repeatedly generate similar

problems (Hirashima, Yokoyama, Okamoto, &

Takeuchi, 2006). Runco (2003) argues that teachers

should show an interest in childrens creative

potential and encourage children to construct their

own personal interpretations of knowledge and

events. Because novice learners find it difficult to

engage in flexible thinking (Mestre, 2002), it is

necessary to support their diverse thinking in our

quest to fostering their creative potentials.

The second hypothesis was to find out the teachers

view about persons who are likely to promote

creativity among the pupils. It was hypothesized that

teachers are more likely to view the promotion of

creativity as a joint responsibility between teachers

and parents. This hypothesis was supported by the

gathered data since the results show that 163 of the

teachers, representing 94.8% view creativity as a

joint effort between teachers and parents, whereas 7,

representing 4.1% view creativity to be the sole

responsibility of teachers, and 2, representing 1.2%

view creativity to be the sole responsibility of parents.

This finding supports those studies that have

established the need for parents to be involved in the

education of their children (e.g., Nyarko, 2010, 2011).

On the issue of the promotion of a conducive learning

climate by the teachers, the result is consistent with

the result of other studies. For instance, Fleith (2000)

found out that in a climate in which fear, one right

answer, little acceptance for a variety of students

products, extreme levels of competition, and many

extrinsic rewards are predominant, it is difficult to

foster high levels of creativity. In fact, the motivation

to be creative rests partly within individuals, but an

individuals social environment also influences

creativity. A positive climate can create an

atmosphere in which creativity and innovation

flourish, whereas a negative one can hinder such

efforts. According to Scott (1965), creative behavior,

a product of the creative individual in a specifiable

contemporary environment, will not occur until both

conditions are met. . . . An unfavorable contemporary

environment will inhibit creative behavior no matter

how talented the individual (p. 213).

When parents become keenly interested in the

education of their children, especially partnering with

teachers, their joint efforts are likely to help in the

identification, nurturing, and fostering the creative

potentials of the children. Lareau (1989, p.253) found

that teachers view their educational activities as

embedded in a larger context and that in order for

classroom work to be effective, it must be supported

by parental involvement in the home. According to

her, parents can help support educational growth

(Lareau, 1989). Using studies by Epstein (1982,

1987) and other teacher surveys she indicated that

teachers want more parent involvement in schooling

In order to avoid stifling the creativity of students, the

teacher needs to provide a friendly and comfortable

environment that students can feel comfortable

67

Am. J. Soc. Mgmt. Sci., 2013,4(2): 63-70

and that parent involvement can increase student

learning, of which creativity is an integral component.

However, the effect of motivation on creativity has

yielded inconsistent results. Whereas researchers

(e.g., Amabile, 1996; Ryan & Deci, 2000) have

underscored the undermining effect of extrinsic

motivation on creativity, others (e.g., Eisenberger &

Rhoades, 2001) have established the enhancing

effect of extrinsic motivation on creativity. In fact,

Eisenberger and Rhoades (2001) found that students

who were promised of a reward for creative acts

increased their creative tasks performance. The

findings of this study show that the teachers do not

see intrinsic and extrinsic motivations as polar

opposites, and that students have to be motivated

only intrinsically to promote their creative drive, but

also extrinsically. This finding demonstrates that

teachers and educators should see intrinsic and

extrinsic motivations as playing a complimentary role

in fostering creativity. In Ghana, where majority of the

citizenry faces economic challenges, neglecting

extrinsic motivations in the promotion of creativity

could be detrimental in nursing the creative potential

in our children.

Thirdly, on the hypotheses finding out from the

teachers whether creativity is intrinsically or

extrinsically motivated, the result indicates that 96 of

the teachers, representing 55.8% view creativity to be

intrinsically motivated whereas 76, representing

44.2% view motivation to be extrinsically motivated. It

appears from the finding that the teachers are split in

their view regarding whether motivation is driven by

forces outside of the person or internally driven by

the persons themselves. Although, the literature

suggests that creative potentials spring from within

the person, extrinsic motivation cannot be overruled

entirelyalthough it does not help (Amabile, 1999).

Fourthly, the hypothesis that posited that teachers

who view motivation to be intrinsically motivated are

more likely to promote it than those who view it as

extrinsically motivated was not supported by the data.

Since it is extant in the literature that intrinsic

motivation relates to creativity, the researchers were

of the view that the teachers were more likely to rely

on intrinsic factors such as interest in the activity

being done, value to be derived in the activity, and

the relevance of the activity in fostering creativity as

juxtaposed with external factors such as rewards and

praises. For over 30 years, psychologists have

studied intrinsic motivation as a wheel upon which

creativity is enhanced (Amabile, 1996). This

orientation is based on the fundamental assumption

that when people enjoy the work itself, they process

information flexibly, experience positive affect, and

become willing to take risks and persist in efforts to

develop and refine ideas (Elsbach & Hargadon, 2006;

Shalley, Zhou, & Oldham, 2004).

The findings of this study have brought to the fore the

critical role of teachers in the country in promoting the

creative exploits of students. It is therefore

recommended that trainee teachers in our colleges of

education, as well as those from our tertiary

education are given the necessary training in skills

and competencies that enable creativity to thrive in

our schools. They should be provided with skills in

motivating children, how to create an enabling

learning atmosphere in the classroom, and not

restricting the thinking trajectories of the pupils.

Teachers in the country, especially, at the basic level

must be trained to teach creatively. These are pillars

that can unearth, nurture, and hold the creativity of

our children.

Also, Lepper and Green (1973) have indicated in

their study that when children are rewarded on tasks

that are intrinsically challenging, the extrinsic rewards

tend to undermine their effort on the task. Although,

intrinsic motivation could provide a fertile ground for

creativity to flourish, it might not be enough due to

personality and cultural differences. According to

(Ryan & Deci, 2000; Silvia, 2008), when employees

are motivated intrinsically, they are drawn to original

perspectives and new discoveries, which attract,

engage, and sustain their interest. But, what is novel

to an individual might not necessarily be useful to

others. In the view of Silvia (2008, p. 58), interest

attracts people to new, unfamiliar things, and many of

these things will turn out to be trivial.

Secondly, the Ghana Education Service should make

the promotion of creativity, especially at our basic

schools a major priority. They should move away

from talking about creativity, and begin acting

creativity. That is they should put in place

interventions in our basic schools that encourage

creativity, and not to undermine it.

Thirdly, school authorities together with teachers

have to put in place avenues that enable them to

collaborate with parents in the fostering of creativity

among school pupils. This is because since children

spend more time at home than in school, parents

must have an idea about certain creative potentials in

their children which the teachers are oblivious to.

This collaborative interaction will be to the mutual

68

Am. J. Soc. Mgmt. Sci., 2013,4(2): 63-70

REFERENCES

benefit of both parents and teachers, as well as the

wider society.

Alexander, P.A., Murphy, P.K., & Woods, B.S. (1994).

Unearthing academic roots: Educators perceptions of

the interrelationship of philosophy, psychology, and

education. Manuscript submitted for publication.

(Personal collection, M.K. Hamza)

Finally, since the results also indicate that there is no

statistical difference between teachers with regard to

whether creativity is intrinsically motivated or

extrinsically motivated, it is expected that teachers

use both in fostering creativity among pupils, and

desist from fixating on one. However, as much as

possible, it is better as teachers to promote the

inherent interest, value, and enjoyment that are

derived from activities that we engaged in.

Amabile, T.M. (1996). Creativity in context. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

Amabile, T. M. (1997). Motivating creativity in

organizations. California management review, 40 (1),

39-58.

Aside the recommendations deduced above, it must

be noted that the study was not conducted without

limitations. The first limitation has to do with the

locations of the schools used in the study. The

sample was drawn on schools that are located in the

cities, and thus the views of teachers in rural schools

are not captured. It is expected that future studies

seek the views of teachers from rural schools. Finally,

it would have been informative if the views of the

students have been sought simultaneously with that

of the teachers to give a clearer picture of how

teachers foster creativity in pupils. Irrespective of the

limitations, the study has shown some of the ways

through which creativity can be fostered in children in

our schools.

Becker, H.J. & Epstein, J. L. (1982). Parent Involvement: A

Survey of Teacher Practices.

CONCLUSION

Drazin, R., Glynn, M. A., & Kazanjian, R. K. (1999).

Multilevel theorizing about creativity in organizations: A

sense making perspective. Academy of Management,

24, 286 -307.

Elementary School Journal. 83(2): 85-102.

Darwin, c. (1859). On the origin of species by means of

natural selection. London: Murray.

Bronfenbrenner,

U.

(1979).

Ecology

of

human

development: Experiments by nature and design.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the

Psychology of discovery and invention. New York,

Harper.

Dent, Jr., H.S. (1995). Job shock: Four new principles

transforming our work and business. New York: St.

Martins Press.

There is no denying the relevance and practical

benefits of creativity to society. The contribution of

creative ideas and products to the advancement of

society has led to the call for the enhancement of

creativity in our schools. As the findings of this study

have shown, teachers, as well as parents have

respective roles to play to ensure that the creative

potentials of pupils are unraveled, nurtured, and

harnessed to the benefit of the pupils in particular,

and society in general.

Elsbach, K. D., & Hargadon, A. B. (2006). Enhancing

creativity through mindless work: A framework of

workday design. Organization Science, 17, 470-483.

Eisenberger, R., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Incremental effects

of reward on creativity. Journal of personality and

social psychology, 18 (4), 728-741.

Epstein, J. L. (1987). Toward a theory of family-school

connections:

Teacher

practices

and

parent

involvement. In Hurrelman, F. X. Kaufman, & F.Losel

(Eds.), social intervention: Potentials and constraints.

Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

In order to achieve this in our schools and since

creativity is the production of something new and

beneficial to society, the school has to lead. This

leadership that the school, and in particular teachers

have to offer should be manifested in the creation of

an enabling learning atmosphere, promotion of

divergent thinking, and motivation. When school

children are operating in an environment that

rewards, and not punish departure from the status

quo, where their views and expression of arts are

appreciated and respected, and are motivated in their

exhibition of novelty, their creative prowess will grow

and flourish.

Fleith, D. (2000). Teacher and Student Perceptions of

Creativity in the Classroom Environment. Roeper

Review, 22 (3), 148-153.

Fryer, M. (2008). Creative teaching and learning in the UK.

In F. Morais & S. Bahia. (Eds.), Criatividade: Cenceito,

Necessidades e Intervencao. Braga, Portugal:

Psiquilibrios.

Fryer, M. (2003). Creativity across the curriculum: A review

and analysis of programmes designed to develop

69

Am. J. Soc. Mgmt. Sci., 2013,4(2): 63-70

creativity. London, UK: Qualifications & Curriculum

Authority.

Fryer, M. (1996). Creative Teaching and Learning. London:

Paul Chapman Publishing.

Pintrich, P.R., Marx, R.W., & Boyle, R.A. (1993). Beyond

cold conceptual change: The role of motivational

beliefs and classroom contextual factors in the process

of conceptual change. Review of Educational

Research, 63, 167-199.

Grainger, T., & Barnes, J. (2006). Creativity in the Primary

Curriculum in J. Arthur, T.

Postman, N. (1993). Technopoly: The surrender of culture

to technology. New York: Random House.

Grainger & D. Wray. (eds.), Learning to Teach in the

Primary School London:

Robinson, K. (2009). The element. How finding your

passion changes everything. New York: Viking Books.

Routledge.pp.209-225.

Runco, M.A. (2003). Education for creative potential.

Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 47(3),

31724.

Hennessdy, B. A. (1997). Teaching for Creative

Development: A Social-Psychological Approach.

Needman Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Robinson. K. (2001). Out of Our Minds Capstone: London

Hirashima, T., Yokoyama, T., Okamoto, M., & Takeuchi, A

(2006). Interactive learning environment by posing

arithmetical word problems as sentence-integration. In

ICCE2006 Workshop Proceedings of ProblemAuthoring, -Generation and -Posing in a ComputerBased Learning Environment (pp. 1-8). International

Conference on Computers in Education 2006, Beijing,

China.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory

and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social

development, and well-being. American Psychologist,

55, 68-78.

Kauffman, D., & Hamza, M. K. (1998). Educational reform:

Ten ideas for change, plus or minus two. Society for

Information Technology & Teacher Education (SITE)

1998; Published Conference Proceeding.

Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., & Oldham, G. R. (2004). The

effects of personal and contextual characteristics on

creativity: Where should we go from here? Journal of

Management, 30, 933-958.

Lareau, A. (1989). Family-School Relationships: A view

from the classroom. Education Policy, 3, no. 3, 245259.

Sharan, S. & Chin Tan, I. (2008). Organizing schools for

productive learning. New York: Springer.

Sarason, S. (1990). The Unpredictable Failure of

Educational Reform. Can we change the course before

its too late? San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Silvia, P. (2008). Interest: The curious emotion. Current

Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 57-60.

Mestre, J. P. (2002). Probing Adults Conceptual

Understanding and Transfer of Learning via Problem

Posing. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,

23, 9-50.

Sternberg, R. (2006). Creativity is a habit. Education Week,

February 22.

Tan, A. G. (1999). Teacher roles in promoting creativity.

Teaching and learning, 19, 43-51.

Nyarko, K. (2010). Parental home involvement: The

missing link in adolescents academic achievement.

Educational Research, 1 (9), 340-344.

Torrance, E. P. (1965). Rewarding Creative Behavior.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nyarko, K. (2011). Parental school involvement: The case

of Ghana. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational

Research and Policy Studies (JETERAPS) 2 (5), 378381.

Torrance, E. P. (1995). Why Fly? Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Torrance, E.P., & Safter, H.T. (1990). The incubation model

of teaching: Getting

Nyarko, K., Assumeng, M., & Atindanbilla, S. (2012). The

understanding and origin of creativity among Ghanaian

basic school teachers. Research Journal in

Organizational Psychology & Educational Studies 1(3)

149-154.

beyond the aha! Buffalo, NY: Bearly Limited.

United Nations (2008). The challenge of assessing the

creative economy: towards informed policymaking.

www.unctad.org/creative-economy.

70

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Books Download The Kite Runner Full Ebook: Book DetailsDokument1 SeiteBooks Download The Kite Runner Full Ebook: Book DetailsIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Books Download The Kite Runner Full Ebook: Book DetailsDokument1 SeiteBooks Download The Kite Runner Full Ebook: Book DetailsIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Additional Information HEREDokument3 SeitenAdditional Information HEREIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Sen Yum Karya Mincer Pens AstraDokument2 SeitenSen Yum Karya Mincer Pens AstraIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Pus TakaDokument1 SeitePus TakaIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Pus TakaDokument1 SeitePus TakaIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pus TakaDokument1 SeitePus TakaIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Ajsms 5 2 33 38Dokument6 SeitenAjsms 5 2 33 38Iqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- AbstractDokument1 SeiteAbstractIqbal Azis SNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Tm3 Transm Receiver GuideDokument66 SeitenTm3 Transm Receiver GuideAl ZanoagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- EI GAS - CompressedDokument2 SeitenEI GAS - Compressedtony0% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Pundit Transducers - Operating Instructions - English - HighDokument8 SeitenPundit Transducers - Operating Instructions - English - HighAayush JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Master Microsoft Excel 2016 text functionsDokument14 SeitenMaster Microsoft Excel 2016 text functionsratheeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- Race Tuning 05-07 KX250Dokument6 SeitenRace Tuning 05-07 KX250KidKawieNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Limestone Problems & Redrilling A WellDokument4 SeitenLimestone Problems & Redrilling A WellGerald SimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Evadeee ReadmeDokument11 SeitenEvadeee Readmecostelmarian2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pierre Schaeffer and The Theory of Sound ObjectsDokument10 SeitenPierre Schaeffer and The Theory of Sound ObjectsdiegomfagundesNoch keine Bewertungen

- IEC 61850 and ION Technology: Protocol DocumentDokument52 SeitenIEC 61850 and ION Technology: Protocol DocumentCristhian DíazNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Sanet - ST Sanet - ST Proceedings of The 12th International Conference On Measurem PDFDokument342 SeitenSanet - ST Sanet - ST Proceedings of The 12th International Conference On Measurem PDFmaracaverikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Memory Performance Guidelines For Dell PowerEdge 12thDokument47 SeitenMemory Performance Guidelines For Dell PowerEdge 12thHuỳnh Hữu ToànNoch keine Bewertungen

- Session Plan (Julaps)Dokument10 SeitenSession Plan (Julaps)Wiljhon Espinola JulapongNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Srinivas ReportDokument20 SeitenSrinivas ReportSrinivas B VNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solid Waste ManagementDokument4 SeitenSolid Waste ManagementAshish DeotaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uptime Detailed SimpleModelDetermingTrueTCODokument9 SeitenUptime Detailed SimpleModelDetermingTrueTCOvishwasg123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Industry 4.0 CourseDokument49 SeitenIndustry 4.0 CourseThiruvengadam CNoch keine Bewertungen

- TranscriptDokument3 SeitenTranscriptAaron J.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Data FNC BatteriesDokument20 SeitenData FNC BatteriessalmanahmedmemonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pub15966 PDFDokument7 SeitenPub15966 PDFIoana BădoiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project ReportDokument10 SeitenProject ReportKaljayee singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Elizabeth Hokanson - Resume - DB EditDokument2 SeitenElizabeth Hokanson - Resume - DB EditDouglNoch keine Bewertungen

- Willy Chipeta Final Thesis 15-09-2016Dokument101 SeitenWilly Chipeta Final Thesis 15-09-2016EddiemtongaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atheros Valkyrie BT Soc BriefDokument2 SeitenAtheros Valkyrie BT Soc BriefZimmy ZizakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety and Reliability in Turbine Sealing CompoundsDokument2 SeitenSafety and Reliability in Turbine Sealing CompoundsProject Sales CorpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nuclear Medicine Inc.'s Iodine Value Chain AnalysisDokument6 SeitenNuclear Medicine Inc.'s Iodine Value Chain AnalysisPrashant NagpureNoch keine Bewertungen

- General DataDokument8 SeitenGeneral DataGurvinderpal Singh MultaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- MiVoice Office 400 Products BR enDokument12 SeitenMiVoice Office 400 Products BR enWalter MejiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Refrigeration Cycles and Systems: A Review: ArticleDokument18 SeitenRefrigeration Cycles and Systems: A Review: ArticleSuneel KallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shinva Pharma Tech DivisionDokument35 SeitenShinva Pharma Tech DivisionAbou Tebba SamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bill of Materials for Gate ValveDokument6 SeitenBill of Materials for Gate Valveflasher_for_nokiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)