Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

7 Predication 2012

Hochgeladen von

LexyyyaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

7 Predication 2012

Hochgeladen von

LexyyyaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

R.

ALBU, Semantics

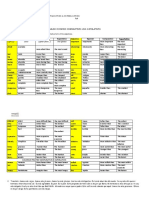

WORKSHEET 7

PREDICATES, REFERRING EXPRESSIONS, AND UNIVERSE OF DISCOURSE

Review exercise:

TEST (1) Say which of the following sentences are equative and which are not:

(a) My parrot is holidaying in the South of France

(b) Dr Kunastrokins is an ass

(c) Tristram Shandy is a funny book

(d) Our next guest is Dr Kunastrokins

(2) Circle the referring expressions in the following sentences:

(a) Basil saw a rat

(b) These matches were made in Sweden

(c) A dentist is a person who looks after people's teeth

(d) Two and two is four.

Preparatory exercise:

In the following sentences, delete the referring expressions and write down the remainder to the right

of the example. the first one is done for you.

(1) My dog bit the policeman

bit

(2) Mr Brown is writing the Mayor's speech

(3) Cairo is in Africa.

(4) Edinburgh is between Aberdeen and York

(5) This place stinks.

(6) John's car is red.

(7) Einstein was a genius.

Definition (partial): The PREDICATOR of a simple declarative sentence is the word (sometimes the

group of words) which does not belong to any of the referring expressions and which, of the

remainder, makes the most specific contribution to the meaning of the sentence.

The predicators in sentences can be of various parts of speech: adjectives, verbs, prepositions and

nouns. Words of other parts of speech, such as conjunctions and articles, cannot serve as

predicators in sentences.

The semantic analysis of simple declarative sentences reveals two major semantic roles played by

different subparts of the sentence. These are the roles of predicator, illustrated above, and the role(s)

of argument(s), played by the referring expressions.

Examples:

Juan is Argentinian predicator: Argentinian, argument: Juan

Juan arrested Pablo predicator: arrest, arg.: Juan, Pablo

Juan took Pablo to Rio pred: take, arg.: Juan, Pablo, Rio

Practice: In the following sentences, indicate the predicators and the arguments as in the above

examples:

(1) Dennis is a menace. pred. ....

arg. ....

(2) Hamish showed Mong his sporran.

(3) Donald is proud of his family.

(4) The hospital is outside the city.

Note: the semantic analysis of a sentence into predicator and argument(s); the syntactic analysis:

into subject and predicate.

But the term "predicate" also has a semantic sense, developed within logic, to be defined below:

Definition: A PREDICATE is any word (or sequence of words) which (in a given single sense) can

function as the predicator of a sentence.

The predicates of a language have a completely different function from the referring expressions.

The roles of these two kinds of meaning-bearing elements cannot be exchanged. Thus John is a

bachelor makes good sense, but Bachelor is a John makes no sense at all. Predicates include

Worksheet 7

words from various parts of speech, e.g., common nouns, adjectives, prepositions and verbs. We

distinguish between predicates of different degrees, (one-place, two-place etc). The DEGREE of a

predicate is a number indicating the number of arguments it is normally understood to have in simple

sentences.

Example Asleep is a predicate of degree one (often called a one-place predicate)

Love is a predicate of degree two (a two-place predicate).

sometimes two predicates can have nearly, if not exactly, the same sense, but be of different

grammatical parts of speech, e.g., My parrot is a talker, My parrot talks).

The distinction between referring expressions and predicates is absolute, without "borderline cases".

However, there are noun phrases, in particular indefinite noun phrases, that can be used in two

ways, either as referring expressions, or as predicating expressions:

John attacked a man. -- a man - referring expression

John is a man. -- a man - predicating expression

EXERCISE

(1) Imagine that you and I are in a room with a man and a woman, and, making no visual sign of any

sort, I say to you, "The man stole my wallet". In this situation, how would you know the referent of

the subject referring expression?

(2) if in the situation described above I had said, "A man stole my wallet", would you automatically

know the referent of the subject expression a man?

(3) So does the definite article, the, prompt the hearer to (try to) identify the referent of a referring

expression?

(4) Does the indefinite article, a, prompt the hearer (to try) to identify the referent of a referring

expression?

The presence of a predicate in a referring expression helps the hearer to identify the referent of a

referring expression. We have just drawn a distinction between referring and identifying the referent

of a referring expression. We will explore this distinction.

EXERCISE

(1) Can the referent of the pronoun I be uniquely identified when this pronoun is uttered?

(2) Can the referent of the pronoun you be uniquely identified when this pronoun is uttered?

(3) Imagine again the situation where you and I are in a room with a man and a woman, and I say to

you (making no visual gestures), "She stole my wallet". Would you be able to identify the referent of

She?

(Answers: Yes (if equating it with the speaker of the utterance is sufficient identification); (2) In many

situations it can, but not always; (3) Yes (that is, in the situation described, if I say to you, "She stole

my wallet", you extract from the referring expression She the predicate female, which is part of its

meaning, and look for something in the speech situation to which the predicate could truthfully be

applied. Thus in the situation envisaged, you identify the woman as the referent of She. If there had

been two women in the room, and no other indication were given, the referent of She could not be

uniquely identified.)

To sum up, predicates do not refer. But they can be used by a hearer - when contained in the

meaning of a referring expression - to identify the referent of that expression. Some more examples

follow:

Worksheet 7

EXERCISE

(1) Does the phrase in the corner contain any predicates?

(2) Is the phrase the man who is in the corner a referring expression?

(3) Do the predicates in the phrase the man in the corner help to identify the referent of the referring

expression in (2) above?

(4) Is the predicate bald contained in the meaning of the bald man?

(5) Is the predicate man contained in the meaning of the bald man?

Speakers refer to things in the course of utterances by means of referring expressions. The words in

a referring expression give clues which help the hearer to identify its referent. In particular,

predicates may be embedded in referring expressions as, for instance, man, in, and corner are

embedded in the referring expression the man in the corner The correct referent of such a referring

expression is something which completely fits, or satisfies, the description made by the combination

of predicates embedded in it.

***

Language is used about things in the real world, like parrots, paper-clips, babies etc. All of these

things exist. But the things we can talk about and the things that exist are not exactly the same.

Language creates unreal worlds and allows us to talk about non-existent things.

The basic, and very safe, definition of reference was: a relationship between part of an

utterance and a thing in the world. But often we use words in a way which suggests that a

relationship exactly like reference holds between a part of an utterance and non-existent things.

The classic case is that of the word unicorn.

EXERCISE

(1) Do unicorns exist in the real world?

(2) In which two of the following contexts are unicorns most frequently mentioned? Circle your

answer:

(a) in fairy stories

(b) in news broadcasts

(c) in philosophical discussions about reference

(d) in scientific text books

(3) Is it possible to imagine worlds different in certain ways from the world we know actually does

exist?

(4) In fairy tale and science fiction worlds is everything different from the world we know?

(5) In the majority of fairy tales and science fiction stories that you know, do the fictional

characters discourse with each other according to the same principles that apply to real life?

(6) Do fairy tale princes, witches, etc. seem to refer in their utterances to things in the world?

Semantics is concerned with the meaning of words and it would be an unprofitable digression to get

bogged down in questions of what exists and what doesn't.... A broad interpretation of the notion

referring expression is the following: any expression that can be used to refer to an entity in the

real world or in any imaginary world will be called a referring expression.

EXERCISE

(1) If unicorns existed, would they be physical objects?

(2) Do the following expressions refer to physical objects?

Worksheet 7

(a) Christmas Day 1980; (b) one o'clock in the morning;

(c) when Eve was born; (d) 93 million miles; (e) eleven hundred;

(f) the distance between the Earth and the Sun; (g) the British national anthem.

Language is used to talk about the perceivable world, and can be used to talk about an infinite

variety of abstractions, and even entities in imaginary, unreal worlds

Universe of discourse

DEFINITION We define the universe of discourse for any particular utterance as the particular

world, real or imaginary (or part real, part imaginary) that the speaker assumes he is talking about

at the time.

EXERCISE

Is the universe of discourse in each of the following cases the real world (as far as we can tell), or a

(partly) fictitious world??

(1) Newsreader on April 14th 1981: "The American space-shuttle successfully landed at Edwards

Airforce Base, California, today."

(2) Mother to child: "Don't touch those berries. They might be poisonous"

(3) Mother to child: "Santa Claus might bring you a toy telephone"

(4) Patient in psychiatric ward: "As your Emperor, I command you to defeat the Parthians"

(5) Doctor to patient: "You cannot expect to live longer than another two months"

(6) Patient (joking bravely): "When I'm dead, I"ll walk to the cemetery to save the cost of a hearse"

These were relatively clear cases. Note that no universe of discourse is a totally fictitious world.

Santa Claus is a fiction, but the toy telephones he might bring do actually exist. So in examples like

this we have interaction between fact and fiction, between real and imaginary worlds. When two

people are 'arguing at cross-purposes", they could be said to be working with partially different

universes of discourse..

EXAMPLE: Theist: "Diseases must serve some good purpose, or God would not allow them"

Atheist: "I cannot accept your premises."

(The atheist's assumed universe of discourse is a world in which God doesn't exist.)

Assuming different universes of discourse is one of the reasons for breakdown of communication

EXERCISE Same universe or different ones?

(1)

A; "Did Jack's son come in this morning?"

B: "I didn't know Jack had a son"

A: "Then who is that tall chap that was here yesterday?"

B: "I don't know but I'm pretty sure Jack hasn't got any kids."

A: "I'm sure Jack's son was here yesterday.

(2) Time traveller from the eighteenth century: "Is the King of France on good terms with the Tzar of

Russia?"

Late twentieth-century person: "Huh?"

(3)

Optician: "Please read the letters on the bottom line of the card."

Patient: "E G D Z Q N B A" Optician: "Correct. well done."

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Metaphor: Art and Nature of Language and ThoughtVon EverandMetaphor: Art and Nature of Language and ThoughtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition (Partial) : The PREDICATOR of A Simple Declarative Sentence Is The Word (Sometimes TheDokument4 SeitenDefinition (Partial) : The PREDICATOR of A Simple Declarative Sentence Is The Word (Sometimes TheSimina MunteanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 ReferenceDokument4 Seiten7 ReferenceIuliana FlorinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 5 Deixis and DefinitenessDokument6 SeitenUnit 5 Deixis and DefinitenessSiti BarokahNoch keine Bewertungen

- How language refers to real and imaginary thingsDokument1 SeiteHow language refers to real and imaginary thingsBianca DarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding PredicatesDokument11 SeitenUnderstanding Predicatesnaldo RoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 5 Predicates: Yes / NoDokument11 SeitenUnit 5 Predicates: Yes / NoHuynh Thi Cam Nhung100% (1)

- Semantics Unit 6 HandoutDokument18 SeitenSemantics Unit 6 HandoutNguyễn Ngọc Quỳnh NhưNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 6 Predicates Referring Expressions and 1Dokument10 SeitenUnit 6 Predicates Referring Expressions and 1Trúc NgânNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2333 Meeting 5. PredicatesDokument6 Seiten2333 Meeting 5. PredicatesUyenNhi TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Predicate, Referring Expression, & Universe of DiscourseDokument35 Seiten3 Predicate, Referring Expression, & Universe of DiscourseNisaafinaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentences, Utterances and PropositionsDokument6 SeitenSentences, Utterances and PropositionsHamid EnglishNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2333 Meeting 2. Sentences, utterances and propositions-3Dokument6 Seiten2333 Meeting 2. Sentences, utterances and propositions-3UyenNhi TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sematics A CoursebookDokument9 SeitenSematics A Coursebooknyce2meetuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 6 Predicates, Referring Expressions, and Universe of DiscourseDokument9 SeitenUnit 6 Predicates, Referring Expressions, and Universe of DiscourseHuynh Thi Cam Nhung0% (1)

- GROUP 3 - Predicate, Referring Expressions and Discourse of UniverseDokument14 SeitenGROUP 3 - Predicate, Referring Expressions and Discourse of Universemillatuz zulfaNoch keine Bewertungen

- METAPHORE & METONIMY - Unit 27Dokument20 SeitenMETAPHORE & METONIMY - Unit 27Siti mukaromahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 1 Semantics NewDokument29 SeitenGroup 1 Semantics NewMar Atul Latifah Jauharin NafiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 1 Semantics NewDokument29 SeitenGroup 1 Semantics NewMar Atul Latifah Jauharin NafiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference and Sense, SensiaDokument8 SeitenReference and Sense, SensiaSensia MirandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching 2333 31455 1654267691 4Dokument25 SeitenTeaching 2333 31455 1654267691 4Alejandro PDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 6, Semantics - VNeseDokument35 SeitenUnit 6, Semantics - VNeseSang NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metaphor ADokument17 SeitenMetaphor ANeferu Florina-madalinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Semantics For Non-Native Speakers of English, Chapter 1Dokument10 SeitenIntroduction To Semantics For Non-Native Speakers of English, Chapter 1cdtancrediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 3 - Reference and Sense-NEWDokument28 SeitenUnit 3 - Reference and Sense-NEWHuynh Thi Cam NhungNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - PragmaticsDokument38 Seiten1 - PragmaticsAravind KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Metaphor and Metonymy of HandDokument21 SeitenA Study On Metaphor and Metonymy of HandKamran business accountNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference and SenseDokument10 SeitenReference and SenseHuynh Thi Cam NhungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pragmatic Meaning: 1. Literal Meaning vs. Utterance MeaningDokument8 SeitenPragmatic Meaning: 1. Literal Meaning vs. Utterance Meaningatbin 1348Noch keine Bewertungen

- Study on Metaphor and Metonymy of the HandDokument21 SeitenStudy on Metaphor and Metonymy of the HandLuis Felipe100% (2)

- Semantic Unit 3 - Part 2 2Dokument15 SeitenSemantic Unit 3 - Part 2 2Uyên HoangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 Utterances, Sentences, PropositionsDokument33 SeitenChapter 6 Utterances, Sentences, PropositionsThu ThanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pragmatics 1: Meaning and ContextDokument21 SeitenPragmatics 1: Meaning and ContextRhean Kaye Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 3: Mia Laras Anggita MunazihahDokument21 SeitenGroup 3: Mia Laras Anggita Munazihahmuna zihahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction to Pragmatics and Language UseDokument28 SeitenIntroduction to Pragmatics and Language UsePop MagdalenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 Sense Relations (Entailment)Dokument7 Seiten0 Sense Relations (Entailment)Roberto Gimeno PérezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 3 Reference and Sense 1Dokument9 SeitenUnit 3 Reference and Sense 1DatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semantics Unit 2 Part 2: Sentences and Propositions-Practice 5 - 1 1Dokument14 SeitenSemantics Unit 2 Part 2: Sentences and Propositions-Practice 5 - 1 1Michelle PepitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Essay of Semantics Group 11Dokument13 SeitenFinal Essay of Semantics Group 11Nguyễn Thị TuyênNoch keine Bewertungen

- Utterance and Ending With A Metarepresentation of An Attributed Thought. Suppose Mary Says (3) To PeterDokument4 SeitenUtterance and Ending With A Metarepresentation of An Attributed Thought. Suppose Mary Says (3) To Peterarth07Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposal Iron Lady - 1Dokument18 SeitenResearch Proposal Iron Lady - 1Demian GaylordNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parsons (1982) - Are There Nonexistent ObjectsDokument8 SeitenParsons (1982) - Are There Nonexistent ObjectsTomas CastagninoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semantics and Pragmatics WorksheetDokument2 SeitenSemantics and Pragmatics WorksheetChiosa AdinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deixis 1Dokument34 SeitenDeixis 1sofiaaltaweelNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 - Chap 2 - Rev PDFDokument21 Seiten03 - Chap 2 - Rev PDFyesikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2Dokument31 SeitenChapter 2CA Pham KhaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER II (Discourse)Dokument20 SeitenCHAPTER II (Discourse)hastizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semantics (1) : Dr. Ansa HameedDokument31 SeitenSemantics (1) : Dr. Ansa HameedZara NurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reference, Denotion and Sense Theory and PracticeDokument3 SeitenReference, Denotion and Sense Theory and PracticeMar CrespoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meaning, Thought, & RealityDokument29 SeitenMeaning, Thought, & RealityDessy FitriyaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- LING2006 - Semantics - 23-24 Week 2 LectureDokument7 SeitenLING2006 - Semantics - 23-24 Week 2 Lecture蘇以正Noch keine Bewertungen

- Linguistic Week 2Dokument4 SeitenLinguistic Week 2Private AccountNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8th Class SyllabusDokument13 Seiten8th Class SyllabusMuhammad FaisalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semantics (CL, Chapter 7.1. and 7.2 Pinker, Chapter 3) : 2. The Conceptual SystemDokument9 SeitenSemantics (CL, Chapter 7.1. and 7.2 Pinker, Chapter 3) : 2. The Conceptual SystemPhoebeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presupposition (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Dokument32 SeitenPresupposition (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Dr-Reham KhalifaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handouts For Semantics GradDokument12 SeitenHandouts For Semantics GradChanh MuốiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name of The Presenters:: 1. Andreana Puji Fatmala (0203521020) 2. Novia Setyana Khusnul K (0203521015)Dokument21 SeitenName of The Presenters:: 1. Andreana Puji Fatmala (0203521020) 2. Novia Setyana Khusnul K (0203521015)muna zihahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key To Chapter 4 PDFDokument4 SeitenKey To Chapter 4 PDFNaseer الغريريNoch keine Bewertungen

- (In) Radden & Dirven - Cognitive English Grammar - Key To ExerciseDokument39 Seiten(In) Radden & Dirven - Cognitive English Grammar - Key To ExerciseNguyen Hoang100% (2)

- Sematics Unit 9 - PT 1-Sense Properties and StereotypesDokument27 SeitenSematics Unit 9 - PT 1-Sense Properties and StereotypesMạch TangNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6b ReferenceDokument4 Seiten6b ReferenceLexyyyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- UtterancesDokument2 SeitenUtterancesLexyyyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curs 12 - Shakespearean Tragedy IIDokument7 SeitenCurs 12 - Shakespearean Tragedy IIMelania MironNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curs 12 - Shakespearean Tragedy IIDokument7 SeitenCurs 12 - Shakespearean Tragedy IIMelania MironNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sense RelationsDokument9 SeitenSense RelationsLexyyyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curs 6 - Renaissance IDokument11 SeitenCurs 6 - Renaissance ILorena RoantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curs 11 - Shakespearean Tragedy IDokument6 SeitenCurs 11 - Shakespearean Tragedy ILexyyyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curs 7 - Renaissance IIDokument11 SeitenCurs 7 - Renaissance IILorena RoantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Child Language DevelopsDokument37 SeitenHow Child Language DevelopsJacob MorganNoch keine Bewertungen

- GESE Exam Information BookletDokument68 SeitenGESE Exam Information BookletAfgoi lowershabelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humboldt and The World of LanguagesDokument20 SeitenHumboldt and The World of LanguagesSthefany RosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aztec Spanish LessonDokument4 SeitenAztec Spanish LessonBrien BehlingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Connecting Words and How To Punctuate Them-Penanda Wacana EnglishDokument5 SeitenConnecting Words and How To Punctuate Them-Penanda Wacana EnglishSyaza MawaddahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Firth and Wagner 2007Dokument20 SeitenFirth and Wagner 2007rubiobNoch keine Bewertungen

- PASS TKT Preparing For The Cambridge Teaching Knowledge Test 2Dokument281 SeitenPASS TKT Preparing For The Cambridge Teaching Knowledge Test 2Leyla Jumaeva100% (1)

- Comparatives and Superlative 1Dokument3 SeitenComparatives and Superlative 1Marioli Vichini Bazan100% (1)

- Suffix & AffixDokument13 SeitenSuffix & Affixahmad awanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pragma-Stylistic Investigation of Proverbs in Yoruba FilmsDokument53 SeitenPragma-Stylistic Investigation of Proverbs in Yoruba FilmsTijani Raheemot Ajedoyin100% (2)

- Numbers and Grammar in Ancient Egyptian LessonsDokument23 SeitenNumbers and Grammar in Ancient Egyptian LessonsTarek AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kerry Hull - The Firt-Person Singular Independent Pronoun en Clasic Ch'olanDokument9 SeitenKerry Hull - The Firt-Person Singular Independent Pronoun en Clasic Ch'olanAngel SánchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tae Whoonearth 04 080522Dokument6 SeitenTae Whoonearth 04 080522api-21516494Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 PDFDokument2 SeitenChapter 4 PDFjgawayenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simple Present TenseDokument2 SeitenSimple Present TenseAlvira DwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Textbook Analysis in SMADokument23 SeitenTextbook Analysis in SMAFarah MulyawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spoken Written CommunicationDokument33 SeitenSpoken Written Communicationapi-262885411Noch keine Bewertungen

- Practical Research 2.9Dokument22 SeitenPractical Research 2.9Michael GabertanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explaining the Compositional Calculation of (A)telicity in English Verb PhrasesDokument15 SeitenExplaining the Compositional Calculation of (A)telicity in English Verb PhrasesjmfontanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adjectives Adverbs ExercisesDokument6 SeitenAdjectives Adverbs ExercisesEleftherios ZoakisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pronouns: Bagja Baihaqi Hakim Muhammad Rifan Maulana Riziq Dwiki Ramadhan Tia Octaviani HermaniaDokument24 SeitenPronouns: Bagja Baihaqi Hakim Muhammad Rifan Maulana Riziq Dwiki Ramadhan Tia Octaviani Hermaniatia octavianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semantics. PrimesDokument256 SeitenSemantics. Primesenrme100% (3)

- Biz LetterDokument10 SeitenBiz LetterHarley QuinnNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOEFL Lesson PlanDokument6 SeitenTOEFL Lesson PlanFree HakkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arithmetic Lesson PlanDokument3 SeitenArithmetic Lesson PlanKennethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baybayin DamoDokument5 SeitenBaybayin DamoRalph RaveloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Pustaka JashdkjasdDokument4 SeitenDaftar Pustaka JashdkjasdFadli AkhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIL - Q3Module 1 REVISEDDokument34 SeitenMIL - Q3Module 1 REVISEDEustass Kidd80% (5)

- OpenMind 1 Unit 10 Grammar and Vocabulary Test BDokument2 SeitenOpenMind 1 Unit 10 Grammar and Vocabulary Test BEdwin Badillo25% (4)

- Tang, Gloria M. and Joan Tithecott. (1999) - Peer Responsein ESL Writing. TeslDokument19 SeitenTang, Gloria M. and Joan Tithecott. (1999) - Peer Responsein ESL Writing. TeslJackHardickaAriesandyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismVon EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayVon EverandThe Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (215)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessVon EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (60)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (30)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYVon EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessVon EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (83)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisVon EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- How to Live: 27 conflicting answers and one weird conclusionVon EverandHow to Live: 27 conflicting answers and one weird conclusionBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (36)

- Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for ThinkingVon EverandIntuition Pumps and Other Tools for ThinkingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (148)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthVon EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (179)

- Philosophy 101: From Plato and Socrates to Ethics and Metaphysics, an Essential Primer on the History of ThoughtVon EverandPhilosophy 101: From Plato and Socrates to Ethics and Metaphysics, an Essential Primer on the History of ThoughtBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (8)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklVon EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (101)

- Buddhism 101: From Karma to the Four Noble Truths, Your Guide to Understanding the Principles of BuddhismVon EverandBuddhism 101: From Karma to the Four Noble Truths, Your Guide to Understanding the Principles of BuddhismBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (78)

- How to Be Free: An Ancient Guide to the Stoic LifeVon EverandHow to Be Free: An Ancient Guide to the Stoic LifeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (324)

- The Mind & The Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental ForceVon EverandThe Mind & The Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental ForceNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsVon EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (8)

- Strategy Masters: The Prince, The Art of War, and The Gallic WarsVon EverandStrategy Masters: The Prince, The Art of War, and The Gallic WarsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- Jung and Active Imagination with James HillmanVon EverandJung and Active Imagination with James HillmanBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Tending the Heart of Virtue: How Classic Stories Awaken a Child's Moral Imagination, 2nd editionVon EverandTending the Heart of Virtue: How Classic Stories Awaken a Child's Moral Imagination, 2nd editionBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)