Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Perinatal Mortality HUKM

Hochgeladen von

Muvenn KannanCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Perinatal Mortality HUKM

Hochgeladen von

Muvenn KannanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

International Journal of Public Health Research Vol 3 No 1 2013, pp (241-248)

PUBLIC HEALTH RESEARCH

Trend of Stillbirths and Neonatal Deaths in University

Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC) From 20042010

Haslina Hassan1, Rosnah Sutan1*, Nursazila Asikin Mohd Azmi1, Shuhaila Ahmad2 and Rohana Jaafar3

1

Department of Community Health, University Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia.

3

Departments of Paediatrics, University Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia.

2

*For reprint and all correspondence: Rosnah Sutan, Department of Community Health, Universiti Kebangsaan

Malaysia Medical Centre, Jalan Yaacob Latif, Bandar Tun Razak, 56000 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur.

Email: rosnah_sutan@yahoo.com or rosnah@medic.ukm.my

ABSTRACT

Accepted

22 February 2013

Introduction

The aim of the Fourth Millennium Developmental Goal is to reduce mortality

among children less than 5 years by two thirds between 1990 and 2015.

Efforts are more focus on improving childrens health. The aim of this study

was to describe the trend of stillbirth and neonatal deaths in University

Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre from 2004 to 2010.

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted using hospital data on

perinatal mortality and monthly census delivery statistics.

There were 45,277 deliveries with 526 stillbirths and neonatal deaths. More

than half of the stillborn cases were classified as normally formed macerated

stillbirth and prematurity was common in neonatal deaths. The trend of SB

and NND was found fluctuating in this study. However, by using

proportionate test comparing rate, there was a transient significant decline of

stillbirth but not neonatal deaths rates between 2004 and 2006. On the other

hand, the neonatal deaths rate showed significant increment from 2006 to

2008. When both mortality rates were compared using proportionate test,

from the start of the study, year 2004 with end of the study, year 2010, there

was no significant decline noted.

Trends of stillbirth and neonatal death rates in University Kebangsaan

Malaysia Medical Centre within 7 years study period did not show the

expected outcome as in Millennium Developmental Goal of two thirds

reduction.

Stillbirth - Neonatal mortality MDG.

Methods

Results

Conclusions

Keywords

241

Improved Trend of Stillbirth

visits being recommended by World Health

Organization6,7. Institutional deliveries in Malaysia

include care given by government and private

sector which contributed 96.6% of all deliveries in

20046.Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical

Centre is an example of institutional delivery

facility and was chosen for this study because it

represents one of the specialist hospitals in Klang

Valley area.

The aim of this study was to describe the

trend of stillbirth and neonatal deaths in University

Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre from 2004 to

2010. Institutional data was used to assess trend of

SB and ND and associated factors.

INTRODUCTION

The fourth goal of the Millennium Development is

to reduce mortality among children under 5 years

old by two thirds between 1990 and 20151,2.

Worldwide, child mortality between 1980 and 2000

was reduced by one third while the neonatal

mortality rate was reduced by only a quarter 1,2. To

achieve MDG 4 goals, the neonatal mortality must

at least be halved2,3. Neonatal mortality is divided

into early and late neonatal death. Early neonatal

deaths occur during the perinatal period and have

similar obstetric origins as the stillbirth2,3.Reasons

for early neonatal deaths includes severe congenital

malformation, premature delivery, antepartum or

intrapartum obstetric complications (foetal

malpresentation or obstructed labour) or because of

harmful practices after birth that leads to infections

1-3

. Besides, another common adverse outcomes of

pregnancy is stillbirth3,4. It accounts for over half of

all perinatal deaths3. Perinatal period is measured

as completed 22 weeks of gestation and ends seven

days after birth3,4. Stillbirth can occur before onset

of labour (antepartum death) or during labour

(intrapartum death)3,4. Foetuses may die before

onset of labour due to pregnancy complications or

maternal diseases3. Distinguishing between these

two types is important. Through appropriate

intrapartum care, stillborn can be avoided.

Intrapartum death also known as fresh stillbirth

(FSB) refers to normal appearance of foetus after

delivery4. Antepartum death also known as

macerated stillbirth (MSB) refers to macerated

looking skin of foetus and implies that death is

more than 12 hours before delivery4.

Stillbirth and neonatal mortality data are

important health status indicators. In Malaysia, the

government and private hospitals data were

analysed by the Division of Family Health

Development and annual report are then produced.

In addition, data related to SB and NND in

specialist hospitals maybe published via their own

hospitals annual report or discussed during

departmental meeting. Suggestions for ongoing

improvement are then advised to prevent another

death in cases similar to the index case. Therefore,

in an attempt to lower the stillbirth rate, screening

and treatment strategies should be developed to

best suited local scene5 .

Vital and mortality statistics, community

survey or hospital data gives an overall estimation

of the problem. However, each has its own

limitation and underreporting is common. In

Peninsular Malaysia, the percentage of institutional

deliveries increased from 75.6% in 1990 to 96.6%

in 20046 . The antenatal coverage in 2008 was

94.4% as compared to 73.4% in year 2000 6. The

average number of antenatal visits by the pregnant

mother to public and private health facilities

increased from 8.4 in 2005 to 9.6 in 2008 7. This

was even higher than the minimum four antenatal

METHODS

This was a retrospective cross sectional study using

Rapid Reporting of Stillbirth and Neonatal Death

form in UKMMC (PNM 1/97) from year 2004 until

2010. National usage of this form was started since

19988. The format is simple, practical and can be

used without autopsy findings because permission

for autopsy is difficult to obtain in Malaysia due to

cultural and religious beliefs9,10. It is only a

reporting system and not a confidential inquiry

system8,10. The classification used was based on a

modified

pathophysiological

Wigglesworth

classification8,9.

UKMMC is located in Cheras, at the

outskirts of Kuala Lumpur but within Klang Valley

area. Klang valley area is the most populated in

Malaysia. It is an institution providing specialist

healthcare and also acted as referral centre for

places across Malaysia as well as from

neighbouring countries11.

All stillbirths and neonatal deaths reported

by UKMMC from 2004 until 2010 were included

in the study. The data of total births by ethnicity,

parity, gestational age, birth weight were collected

from the monthly census data which was kept in

the census files in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Department. Data were grouped as maternal

related, and foetal related factor. Maternal related

factors are ethnicity, citizenship, age, parity status,

methods for gestational age estimate, antenatal

clinic follow up and maternal medical illnesses.

Foetal related factors includes place of delivery,

who delivered the cases, plurality of pregnancy,

birth weight and sex of the foetus. Exclusion

criteria were incomplete forms which cannot be

verified further. There were 526 forms collected

and 2 (0.4%) forms were rejected because of

incompleteness. Routinely, the form is filled by

the attending doctor on the delivery day of the

stillborn or on the day of death for the neonate.

In this study, stillbirth is defined as a birth

of a dead foetus of at least 22 weeks of gestation or

weighing at least 500grams12. Early neonatal deaths

were deaths of live born babies during the first

seven completed days after birth, and late neonatal

242

International Journal of Public Health Research Vol 3 No 1 2013, pp (241-248)

deaths occurred after 7 completed days and before

28 completed days 3,12. Neonatal mortality includes

early and late neonatal deaths, the rates are given

per 1000 live births3 .Stillbirth rates are reported as

stillbirth beyond a certain gestational age (more

than 22 week or 500g) divided by the number of

total birth12.

Age of a mother is based on the date of

birth stated in the identity card. For those without

identity card, the age is obtained through admission

data. Ethnic group is divided to Malay, Chinese,

Indian or Others (Murut, Bajau, Melanau, Bidayuh,

Kadazan/Dusun, Iban, Orang Asli and noncitizens).

Low birth weight is birth weight less than 2500g3.

Birth weight is determined by duration of gestation

and rate of foetal growth. Infants with birth weight

less than 2500g can be either born prematurely

(preterm birth) or born small for gestational age

(SGA; a proxy for intra uterine growth restriction,

IUGR)13. Preterm birth is delivery before 37

completed weeks of gestation3. Gestational age at

delivery is calculated based on the first day of the

last normal menstrual period till delivery occurs.

Those with revised estimated delivery date were

categorized under ultrasound based estimation.

Gestational age is expressed in completed days or

completed weeks3.

Data was analysed using Statistical

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc. Chicago

USA) version 19.0 for descriptive analyses.

Proportionate tests were conducted to assess rate

significance.

RESULTS

Total deliveries reported in UKMMC from year

2004 to 2010 were 45 277. There were 44,994 live

births, 453 perinatal deaths and 241 neonatal

deaths. Of the perinatal deaths, 283 (54%) were

stillbirths. Out of the stillbirths, 168 (32.1%) were

macerated stillbirths and 115 (21.9%) were fresh

stillbirths. Of the neonatal deaths, 170 (32.3%)

were early deaths and 71 (13.5%) were late

neonatal deaths.

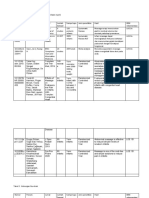

Table 1 shows maternal related factors of

the cases. Majority of the patients were Malay

(88.5 %), with Malaysian citizenship (89.7%), age

more than 35 (79.7%), with multiparity (57.1%)

with 92.7% had antenatal clinic follow-up and

45.9% had specialist clinic follow-up.

Table1 Characteristics of cases according to maternal related factors

Cases

n

SB

N

ND

n

Ethnicity

Malay

Chinese

Indian

Others

336

107

20

7

170

64

14

4

67.5

25.4

5.5

1.6

166

43

6

3

76.1

19.7

2.8

1.4

Citizenship

Yes

No

471

53

252

31

89.0

11.0

219

22

90.9

9.1

Maternal age

< 35

35

403

103

206

62

76.9

23.1

197

41

82.8

17.2

Parity

0

1-4

>5

207

296

15

122

144

12

43.9

51.8

4.3

85

152

3

35.4

63.3

1.3

ANC Follow up

Yes

No

484

37

254

26

90.7

9.3

230

11

95.4

4.6

72

41

14.6

31

11.8

349

180

64.3

169

64.5

1.1

1.2

Place of ANC

follow up

Government Health

Clinic

Hospital

with

specialist

Hospital

without

243

Improved Trend of Stillbirth

specialist

Private

clinic/hospital

Gestational

age

estimated

Last

menstrual

period

Ultrasound

Neonatal assessment

Unknown

Maternal

medical

illness

Hypertension

Diabetes

Vaginal bleeding

Anemia

Prolonged rupture of

membrane

Preterm labour

Other illness

115

56

20

59

22.5

388

109

3

23

210

53

2

17

74.5

18.8

0.7

6.0

178

56

1

6

73.9

23.2

0.4

2.5

68

33

25

17

37

45

21

16

12

16

13.0

6.1

4.6

3.5

4.6

23

12

9

5

21

9.6

5.0

3.8

2.1

8.8

369

35

210

25

60.9

7.3

159

10

66.5

4.2

Abbreviations: n, total cases (of SB and ND)

For those with other illness, there were

four cases of thyrotoxicosis, three cases of

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and three

cases of Thalassemia trait.

Table 2 shows the foetal related factors.

One third of the cases was below 27 week of

gestation (30.2%) and delivered

hospital (93.5%). Majority were

doctors (90.5%), singleton (90.0%),

than 2500 gram (81.3%) and of

(56.6%).

at specialist

delivered by

weighing less

male gender

Table 2 Characteristics of cases according to foetal related factors.

Cases

n

SB

n

ND

n

Gestational age

< 27 W

28- 32 W

33 36 W

> 37 W

147

120

110

109

77

69

64

46

30.0

27.0

25.0

18.0

70

51

46

63

30.4

22.2

20.0

27.4

Place of delivery

Home

Hospital with specialist

Private clinic/hospital

9

487

24

2

265

15

0.7

94.0

5.3

7

222

9

2.9

93.3

3.8

Delivery by

Doctors

Not doctors

475

49

248

35

87.6

12.4

227

14

94.2

5.8

Number of foetus

Singleton

Non singleton

471

50

254

26

90.7

9.3

217

24

90.0

10.0

Birth weight

Less than 2500g

More than 2500g

416

96

229

44

83.9

16.1

187

52

78.2

21.8

244

International Journal of Public Health Research Vol 3 No 1 2013, pp (241-248)

Sex of baby

Male

Female

Undetermined/unknown

Abbreviations: n, total cases

268

209

17

154

120

9

Table 3 showed normally formed

macerated stillbirths (NFMSB) accounted for

53.2% of deaths in stillbirth cases. In early and late

neonatal death, prematurity was the common cause

of death. Prematurity comprised 50.3% of the early

neonatal deaths and 53.5% in late neonatal deaths.

The mean birth weight in stillbirths was 1439.6

955 grams, whereas in the neonatal deaths, the

mean was 1699 945grams.

Figure 1 showed trend of SB and ND rates

from 2004-2010. The stillbirth rate declined from

54.4

42.4

3.2

114

89

8

54.0

42.2

3.8

8.1 per 1000 total births in 2004 to 6.2 in 2010. The

neonatal mortality rate has increased from 5.1 per

1000 live births in 2004 to 5.8 in 2010. There is a

transient decline in 2006 for both components of

mortality rates with significant decline seen in SB

rates but not ND. The significant transient

increment of ND was noted from 3.3 in 2006 to 7.7

in 2008. Using proportionate test, there was no

significant changes from year 2004 compared to

year 2010 for both mortality rates.

Table 3 Distribution of causes of death according to Wigglesworth Classification of Death

Cause

of

death

Stillbirth

Early neonatal deaths

according to WPC

n

%

n

%

LCM

45

16.2

59

35.0

NFMSB

148

53.2

Birth

84

30.2

17

10.0

asphyxia

Prematurity

85

50.3

Infection

4

2.37

Others

1

0.6

Unknown

1

0.36

3

1.78

Total

278

100

169

100

WPC = Wigglesworth Pathophysiological Classification

LCM = Lethal Congenital Malformation

NFMSB = Normally Formed Macerated Still Birth

Abbreviations: SB, stillbirth; NMR, neonatal mortality rate

Figure 1 Stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates, 2004- 2010 in UKMMC

245

Late neonatal deaths

n

%

19

26.7

5

7.04

38

9

71

53.5

12.7

100

Improved Trend of Stillbirth

Wigglesworths classification was to divide cases into

groups with clear implications for clinical

management. Cases may present in a vague manner.

Classifications are then based on combination of

clinical data and pathological findings18. This figure

could be underestimated due to pathophysiological

approach in reporting deaths in contrast to autopsy or

post-mortem. In addition, investigations on infection

were conducted after loss had occurred. Infection that

presented earlier would be resolved by the time

investigations were done. In other classification, for

example Neonatal and Intrauterine Death Classification

according to Etiology (NICE), it aimed to identify

underlying biological causes of death and not areas of

healthcare provision like Wigglesworths. For example

by using NICE, placenta abruption is identified as

cause of death and not intrauterine death, asphyxia or

immaturity which was the result of the abruption and

lead to death18. Therefore different classifications used

will produce different causes of death for the same set

of data.

This study findings about classification of

neonatal deaths also concurred with the Annual Report

2008 of Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Prematurity,

lethal congenital malformations and asphyxia

conditions were the main causes of neonatal deaths in

Malaysia12. To reduce such causes, the strategy

identified was to strengthen the pre-pregnancy and

antenatal care12. For example in Singapore, prenatal

screening of genetic disorders like Haemophilia has

reduced the average case of -Thalassaemia major of

15 to 20 cases a year to that of one case per year 19. In

Malaysia, history of rubella vaccination during school

years has improved rubella sero-positivity among

antenatal mothers 20.

Women who lacked antenatal care are at risk

for stillbirths4. Antenatal care is one of the pillars for

Safe Motherhood Initiatives21. By attending antenatal

clinic women are exposed to health education and were

taught the essential warning signs and symptoms

during pregnancy which can result in saving her life

and pregnancy. Ministry of Health Malaysia had

produced series of Perinatal Care Manual since 2002

which can be referred as guidance for health care

workers. The Manual consists of five sections: prepregnancy care, antenatal care, intrapartum care,

postpartum care and neonatal care7,22,25. However in

this result, more than 90% of the cases had antenatal

clinic follow up but there is difficult to ascertain the

quantity or earliest booking period of the cases as this

was not captured by the format.

Inadequate antenatal care is one of the

common risk factors for stillbirths in developing

countries4,5. In Malaysia, screening strategies include

foetal kick charts (Cardiff count to ten) which is the

indirect tool to monitor foetal wellbeing26,28 and most

health clinics are equipped with ultra sound for foetal

growth assessment. However, in our data most stillborn

occurred prior to 27 week and the foetal kick chart is

DISCUSSION

This study shows that stillbirths were the commonest

cause for perinatal deaths in UKMMC. This is

consistent with most studies done in analyzing

perinatal deaths 12,14,15. The stillbirths and neonatal

mortality rates in this study were higher compared to

the figures reported in Annual Report of Stillbirth and

Neonatal Deaths in Malaysia 2003-2006 or from

Department of Statistics, Malaysia 1998-20067. This

discrepancy could be due to deaths from complicated

cases managed in such tertiary referral center. In

addition, different definition of death was used. For

example, the Department of Statistics used 28 week

gestational age as the definition of death12. Another

reason is the differences in method of how notification

form was analyzed in Ministry of Health compared to

specialist hospitals. In public hospitals, the

notifications will eventually be submitted to the

national level whereby the findings will be tabulated

based on the patients residential address categorized

by states. This is because the patient may receive

antenatal care from one state in Malaysia but delivered

eventfully at another state. This differs to this study as

data collected were based on place of death i.e.

UKMMC. Nevertheless, the overall trend of SB rates

was not declining significantly.

Since there was a significant transient decline

in SB rate in 2004-2006, some intervention could have

been taken place prior to the study. Underreporting is

unlikely since notification was done by the respective

ward where death has taken place and it has been

counter check with monthly census.

There was non-significant transient declined

of neonatal mortality from 5.1 in 2004 to 3.3 in 2006.

In UKMMC, the neonatal resuscitation program (NRP)

was implemented in1998. The outcome of the program

was reviewed from 1996 to 2004 and concluded that

NRP was associated with improvement of neonatal

mortality rates16. However, the Malaysian NRP success

has yet to be reviewed since the last study which was

done in 2004. Given the circumstances of transient

significant increment of ND rate from 3.3 in 2006 to

7.7 in 2008, other factors besides the NRP could also

be at fault and further study is warranted. Factors such

as staffing, facilities, intrapartum interventions,

paediatric factors and parental data have been found to

have significant associations 17. However, no published

data available related to any intervention done in

UKMMC to explain this increment.

In developing countries, infection is estimated

to contribute to 25-50% of the stillbirths4,5. This is in

contrast to this study result. As mentioned previously,

NFMSB are the predominant classification (53.2%) of

deaths among stillbirth. This result is similar as

produced by the Report of Stillbirths and Neonatal

Deaths by Ministry of Health Malaysia. Infection as

the classification of death was none in the analysis of

stillbirth category as opposed to 15.1% as the cause of

death in live births. This is because the aim of the

246

International Journal of Public Health Research Vol 3 No 1 2013, pp (241-248)

only given from 28 weeks gestation onwards. Perhaps

other screening strategies can be employed earlier in

second trimester rather than at the end of trimester.

Perinatal Care Manual mentioned that antenatal

booking should start as early as 12 weeks gestation26.

Ultrasound is used during booking visit depending on

the facilities at the clinics. Symphysio-fundal height

(SFH) tape measurement is performed routinely from

22 weeks of gestation. If there is a discrepancy

between the SFH and gestational age, patient will also

be referred for ultrasound24. Antenatal coverage in

Malaysia in 2008 was 94.4% with increase in average

number of antenatal visits as well7. Malaysians

antenatal coverage has been extensive as also

evidenced by increasing number of health clinics and

hospitals by the Malaysian Plans7. The health clinic has

its own specialist known as the Family Medicine

Specialist (FMS). The FMS is responsible for receiving

and handling cases referred to him or her and will

ensure the cases seen are in accordance with clinical

practice guidelines established by the Ministry of

Health Malaysia. The FMS can refer complicated cases

to tertiary hospitals. Therefore infrastructure,

manpower and equipment seem to be adequate.

Perhaps, public need to be educated on importance of

early antenatal booking, especially those with high risk

factors for adverse outcomes in pregnancy.

Further analysis of the trend by gestational

age per year showed that stillbirth rates were highest

among those with gestational age less than 27 week

and of low birth weight (i.e. less than 2500 grams). The

mean birth weight for stillbirth cases was 1439.6

grams. This strongly puts across the message that

stillbirth is a result of low birth weight because of early

gestation of delivery. Risk factor for low birth weight

babies are poor maternal nutritional status27-29,

advanced maternal age4, low economic status27-,29.

Indian race27, unbooked28 and pre eclampsia 4,28,29. In

this study it is impossible to measure the maternal

nutritional status as the parameter was not considered

in the format. The mean maternal age for stillbirths (30

years old 5.8) and neonatal deaths (30 years old 4.8)

did not differ much and the possible explanation is that

the majority of the population that utilize the health

care facilities is from the age of 35 years and less

which made up 80% of the total cases.

2.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

15.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

We would like to express appreciation to staff of

Obstetrics & Gynecology UKMMC for their help and

support. Besides a note of thanks to the Ethical

Committee of University Kebangsaan Malaysia for

approving this study (UKM-CGPM-TKP-070-2010).

16.

17.

REFERENCES

1.

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, Lancet

Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million

neonatal deaths: Lancet. 2005; 365(9462):891900.

247

WHO SEARO. Operationalizing the Neonatal

Health Care Strategy in SouthEast Asia

Region 11th Meeting of Health Secretaries of

Member States of SEARO New Delhi India.

2006.

World Health Organization. Neonatal and

Perinatal Mortality Country Regional and

Global Estimates. 2006.

McClure

EM,

Nalubamba-Phiri

M,

Goldenberg RL. Stillbirth in developing

countries.Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;

94(2):82-90.

Goldberg R, McClure E, Belizan J. Reducing

the worlds stillbirths. BMC Pregnancy and

Childbirth. 2009; 9(Suppl 1), S1.

Chee HL, Barraclough S. Health care in

Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur:Taylor& Francis;

2007.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Annual Report

2008: Family Health Development Malaysia.

2009.

Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Annual Report

1998. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in

Malaysia The National Technical Committee

on Perinatal Health. 2000.

Amar HS, Maimunah AH, Wong SL. Use of

Wigglesworth

pathophysiological

classification for perinatal mortality in

Malaysia. Arch Dis Child Foetal Neonatal Ed.

1996;74 (1):F56-9.

Sutan R. A review of determinant factors of

stillbirths in Malaysia. Journal Community

Health. 2008;14: 68-77.

Malaysia Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan

Malaysia (HUKM). External Evaluator Field

Survey.http://www.jica.go.jp/english/operatio

ns/evaluation/oda_loan/post//pdf/e_project32_

full.pdf. 2008.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Report on

Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in Malaysia

2003-2006. Kuala Lumpur: 2009.

World Health Organization. Health statistics

and health information systems. 2011.

Sameshima H, Ikenoue T. Risk factors for

perinatal deaths in Southern Japan:

Population-based analysis from 1998 to 2005.

Early Human Development. 2007;84:319-323.

Barfield WD, Tomashek KM, Flowers LM,

Iyasu S. Contribution of late foetal deaths to

US perinatal mortality rates, 1995-1998.

SeminPerinatol. 2002; 26(1):17-24.

Boon NY. Singapore Med J. Neonatal

resuscitation programme in Malaysia: an

eight-year experience. 2009; 50:152-60.

Joyce R, Webb R, Peacock JL. Associations

between perinatal interventions and hospital

stillbirth rates and neonatal mortality. Arch dis

Child Foetal Neonatal Ed .2004;89:F51-F56.

Improved Trend of Stillbirth

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

Winbo IG, Serenius FH, Dahlquist GG, Klln

BA. NICE, a new cause of death classification

for stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Int J

Epidemiol. 1998; 27(3):499-504.

Tan A.2011 Prenatal Genetic Screening and

Testing [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2012 Jan 18].

Available

from:

http://www.bioethics.singapore.org/.

Zekawi Z, Muizatul W, Marlyn M, Jamil M,

Illina I. Rubella vaccination programme in

Malaysia: Analysis of a seroprevalence study

in an antenatal clinic. Med J Malaysia. 2005;

60:345-9.

Bloom S, Lippeveld T, Wypij D. Does

antenatal care make a difference to safe

delivery? A study in urban Uttar Pradesh,

India. Health Policy and Planning.1999;14:3848.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Perinatal Care

Manual: Intrapartum Care. Kuala Lumpur:

2010.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

248

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Perinatal Care

Manual: Pre pregnancy. Kuala Lumpur: 2010.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Perinatal Care

Manual: Antenatal Care. Kuala Lumpur: 2010.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Perinatal Care

Manual: Neonatal Care. 2010.

Eeng TA and MohamadRazi ZR. Pregnancy

guidelines for Malaysian women. Kuala

Lumpur: National University of Malaysia;

2007.

Mahmud AB, Sallam AA. Analysis of birth

weight data from the Malaysian Family Life

Survey II.Asia Pac J Public Health. 1999;

11(2):71-6.

Singh G, Chouhan R, Sidhu M. Maternal

Factors for Low Birth Weight Babies. Medical

Journal of Armed Forces India.2009; 65: 1012.

Kramer MS. The epidemiology of adverse

pregnancy outcomes: an overview. J Nutr.

2003;133(5 Suppl 2):1592S-6S.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Original Article: Pregnancy Outcome Between Booked and Unbooked Cases in A Tertiary Level HospitalDokument6 SeitenOriginal Article: Pregnancy Outcome Between Booked and Unbooked Cases in A Tertiary Level HospitalNatukunda DianahNoch keine Bewertungen

- McKay Et Al PAFs Complete Cases PDFDokument10 SeitenMcKay Et Al PAFs Complete Cases PDFAnonymous oAoEj7pzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secular Trends of Macrosomia in Southeast China, 1994-2005: Researcharticle Open AccessDokument9 SeitenSecular Trends of Macrosomia in Southeast China, 1994-2005: Researcharticle Open AccesskymalogaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claudio Et Al HE Vol 3Dokument17 SeitenClaudio Et Al HE Vol 3Elizalde HusbandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perinatal Factor Journal PediatricDokument8 SeitenPerinatal Factor Journal PediatricHasya KinasihNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019Dokument1 SeiteMaternal and Perinatal Maternal and Perinatal Outcome of Maternal Obesity Outcome of Maternal Obesity at RSCM in 2014-2019 at RSCM in 2014-2019heidi leeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Factors and Long-Term Health Consequences of MacrosomiaDokument6 SeitenRisk Factors and Long-Term Health Consequences of MacrosomiaKhuriyatun NadhifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metgud Factors Affecting Birth Weight of A Newborn - A Community Based Study in Rural Karnataka, IndiaDokument4 SeitenMetgud Factors Affecting Birth Weight of A Newborn - A Community Based Study in Rural Karnataka, IndiajanetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proforma Synopsis For Registration of SubjectDokument15 SeitenProforma Synopsis For Registration of SubjectTamilArasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salinan Terjemahan 808-1523-1-SMDokument17 SeitenSalinan Terjemahan 808-1523-1-SMfatmah rifathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sapna Triyaningsih - Keperawatan Maternitas 1.id - enDokument5 SeitenSapna Triyaningsih - Keperawatan Maternitas 1.id - enSapna TriyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birth Intervals and Associated Factors Among Women Attending Young ChildDokument12 SeitenBirth Intervals and Associated Factors Among Women Attending Young ChildSintayehu BirhanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- SDL ActivitiesDokument11 SeitenSDL Activitiesella retizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protocol Poojitha CompletedDokument15 SeitenProtocol Poojitha CompletedPranav SNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2159-Article Text-4965-1-10-20230310Dokument7 Seiten2159-Article Text-4965-1-10-20230310najwaazzahra2121Noch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence and Risk of Moderate Stunting Among A Sample of Children Aged 0-24 Months in BruneiDokument12 SeitenPrevalence and Risk of Moderate Stunting Among A Sample of Children Aged 0-24 Months in BruneishandyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence and Risk of Moderate Stunting Among A Sample of Children Aged 0-24 Months in BruneiDokument11 SeitenPrevalence and Risk of Moderate Stunting Among A Sample of Children Aged 0-24 Months in BruneiDnr PhsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevalence and Determinant of Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Adolescent MotherDokument8 SeitenPrevalence and Determinant of Exclusive Breastfeeding Among Adolescent MothermaulidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 Nres WD Revision For The PrintDokument84 Seiten2014 Nres WD Revision For The Printzozorina21Noch keine Bewertungen

- NICHD calculator predicts outcomes for extremely preterm infantsDokument5 SeitenNICHD calculator predicts outcomes for extremely preterm infantsMarce FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Khan 2020 Ic 200031Dokument3 SeitenKhan 2020 Ic 200031Lezard DomiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Programme On Pregnancy Induced Hypertension Among Antenatal Mothers in Selected Areas of RaichurDokument19 SeitenA Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Programme On Pregnancy Induced Hypertension Among Antenatal Mothers in Selected Areas of Raichursanvar soniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 521 2345 1 PB Converted 1Dokument14 Seiten521 2345 1 PB Converted 1prabuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Associated With Home Maternal Deliveries in Rural AreasDokument24 SeitenFactors Associated With Home Maternal Deliveries in Rural AreasJASH MATHEW100% (1)

- Babies Born To Obese Mothers: What Are The Characteristics and Outcomes?Dokument8 SeitenBabies Born To Obese Mothers: What Are The Characteristics and Outcomes?IJPHSNoch keine Bewertungen

- 173641-Article Text-444853-1-10-20180622Dokument9 Seiten173641-Article Text-444853-1-10-20180622Alimatu AgongoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fetomaternal Outcome in Advanced Maternal Age Protocol PDFDokument25 SeitenFetomaternal Outcome in Advanced Maternal Age Protocol PDFGetlozzAwabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 UN Reddy EtalDokument6 Seiten6 UN Reddy EtaleditorijmrhsNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Retrospective Study To Know The Perinatal Mortality Rate and Its Sequence in Nishter Hospital MultanDokument5 SeitenA Retrospective Study To Know The Perinatal Mortality Rate and Its Sequence in Nishter Hospital MultaniajpsNoch keine Bewertungen

- InformaciónDokument6 SeitenInformaciónVIOLETA JACKELINE ARMAS CHAVEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Levels, Timing, and Etiology of Stillbirths in Sylhet District of BangladeshDokument10 SeitenLevels, Timing, and Etiology of Stillbirths in Sylhet District of Bangladeshayu_pieterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yus Tentang RetplasDokument8 SeitenYus Tentang Retplasaulya zalfaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternal and Child Health in NepalDokument51 SeitenMaternal and Child Health in NepalAdhish khadkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ijpedi2021 5005365Dokument8 SeitenIjpedi2021 5005365KimberlyjoycsolomonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional StudyDokument15 SeitenDelays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional Studykaren paredes rojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hubungan Umur Dan Paritas Ibu Dengan Kejadian Berat Badan Lahir Rendah Di Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah DR Ahmad Mohctar Kota Bukittinggi Tahun 2014Dokument8 SeitenHubungan Umur Dan Paritas Ibu Dengan Kejadian Berat Badan Lahir Rendah Di Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah DR Ahmad Mohctar Kota Bukittinggi Tahun 2014agus putraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acid Jurnal 4Dokument7 SeitenAcid Jurnal 4awaloeiacidNoch keine Bewertungen

- School of Health and Allied Health Sciences Nursing DepartmentDokument4 SeitenSchool of Health and Allied Health Sciences Nursing DepartmentJeane Louise PalmeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternal Death ReviewsDokument4 SeitenMaternal Death ReviewsJosephine AikpitanyiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research ArticleDokument9 SeitenResearch ArticleFhasya Aditya PutraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knowledge on Janani Suraksha Yojana among antenatal mothersDokument18 SeitenKnowledge on Janani Suraksha Yojana among antenatal motherspallavi sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Komplikasi Persalinan Dengan Riwayat Kehamilan Resiko TinggiDokument7 SeitenKomplikasi Persalinan Dengan Riwayat Kehamilan Resiko TinggiUssiy RachmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faktor determinan proksi kematian neonatus di Kabupaten Buton UtaraDokument8 SeitenFaktor determinan proksi kematian neonatus di Kabupaten Buton UtaraDeliaihda MufidahNoch keine Bewertungen

- maternal risk factors associated with term LBW infantsDokument9 Seitenmaternal risk factors associated with term LBW infantsLydia LuciusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Jurisprudence ProjectDokument11 SeitenMedical Jurisprudence ProjectUtkarshini VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Katherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1Dokument4 SeitenKatherine J Gold Sheila M Marcus: Table 1angelie21Noch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Factors for Low Birth Weight in MalaysiaDokument5 SeitenRisk Factors for Low Birth Weight in Malaysiaerine5995Noch keine Bewertungen

- Okolie Stephaine 1-3Dokument11 SeitenOkolie Stephaine 1-3Confidence BlessingNoch keine Bewertungen

- P H A R M A C e U T I C A L S C I e N C e SDokument7 SeitenP H A R M A C e U T I C A L S C I e N C e SBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Neonatal DeathsDokument12 SeitenEarly Neonatal DeathsShahla AlalafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hubungan Preeklamsi Berat Dengan Kelahiran PretermDokument10 SeitenHubungan Preeklamsi Berat Dengan Kelahiran PretermVera Andri YaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hubungan Preeklamsi Berat Dengan Kelahiran Preterm Di Rumah Sakit Umum Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat 2013Dokument10 SeitenHubungan Preeklamsi Berat Dengan Kelahiran Preterm Di Rumah Sakit Umum Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat 2013Vera Andri YaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volume 3 Issue 1 2023: © Nijrms Publications 2023Dokument6 SeitenVolume 3 Issue 1 2023: © Nijrms Publications 2023PUBLISHER JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breast Feeding ModifiedDokument16 SeitenBreast Feeding ModifiedTilahun MikiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternity Led CareDokument7 SeitenMaternity Led CareNeelShwapnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Prediction of Preterm Birth For Singleton, Twin, and Triplet PregnanciesDokument6 SeitenEarly Prediction of Preterm Birth For Singleton, Twin, and Triplet PregnanciesNi Wayan Ana PsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seajphv2n1 p47Dokument5 SeitenSeajphv2n1 p47Nilu MalvinnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abebaw 2020Dokument10 SeitenAbebaw 2020Eva SihalohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knowledge Attitudes and Practices Regarding ModernDokument7 SeitenKnowledge Attitudes and Practices Regarding Modernnaasir abdiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contraception for the Medically Challenging PatientVon EverandContraception for the Medically Challenging PatientRebecca H. AllenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thoracic Trauma 980Dokument45 SeitenThoracic Trauma 980Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Trauma and Life Support (Atls) : by Anu Sandhya PG Ward 3Dokument34 SeitenAdvanced Trauma and Life Support (Atls) : by Anu Sandhya PG Ward 3Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6.examination of Inguinal SwellingDokument4 Seiten6.examination of Inguinal SwellingMuvenn Kannan100% (1)

- Pyrexia of Unknown OriginDokument4 SeitenPyrexia of Unknown OriginMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Single Best Answer Emergency MedicienDokument11 SeitenSingle Best Answer Emergency MedicienMuvenn Kannan100% (1)

- Managing Hypertension in PregnancyDokument8 SeitenManaging Hypertension in PregnancyMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Age Related Macular DegenerationDokument35 SeitenAge Related Macular DegenerationMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ospe 12Dokument2 SeitenOspe 12Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cirrhosis 2 and SBPDokument56 SeitenCirrhosis 2 and SBPMuvenn Kannan100% (1)

- Meq 1 Paediatrics: Marks)Dokument4 SeitenMeq 1 Paediatrics: Marks)Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MEQ On BPPVDokument5 SeitenMEQ On BPPVMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fam 2 MCQDokument20 SeitenFam 2 MCQMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pleural Effusion OSPEDokument2 SeitenPleural Effusion OSPEMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rheumatoid Arthritis MEQDokument3 SeitenRheumatoid Arthritis MEQMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gastric Carcinoma: H. Pylori InfectionDokument7 SeitenGastric Carcinoma: H. Pylori InfectionMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intestinal Obstruction 3Dokument27 SeitenIntestinal Obstruction 3Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthopedics MCQs With AnswersDokument32 SeitenOrthopedics MCQs With AnswerslanghalilafaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colorectal CancerDokument39 SeitenColorectal CancerMuvenn Kannan100% (2)

- Ocular Emergencies: Immediate TreatmentDokument86 SeitenOcular Emergencies: Immediate TreatmentBenny Franclin SuripattyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organicbrainsyndrome 130619180626 Phpapp02Dokument46 SeitenOrganicbrainsyndrome 130619180626 Phpapp02Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intestinal Obstruction2Dokument26 SeitenIntestinal Obstruction2TwinkleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enzymes Exam PaperDokument2 SeitenEnzymes Exam PaperMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obs and Gynecology Placenta AcrretaDokument2 SeitenObs and Gynecology Placenta AcrretaMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intestinal Obstruction 4Dokument25 SeitenIntestinal Obstruction 4Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intestinal ObstructionDokument25 SeitenIntestinal ObstructionMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supraventricular Arrhythmias (Seminar)Dokument29 SeitenSupraventricular Arrhythmias (Seminar)Muvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECG Changes in Chamber EnlargementDokument16 SeitenECG Changes in Chamber EnlargementMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology Membrane ExamDokument9 SeitenBiology Membrane ExamMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supervised wound procedures guideDokument50 SeitenSupervised wound procedures guideMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breastfeeding Benefits and Risks of JaundiceDokument81 SeitenBreastfeeding Benefits and Risks of JaundiceMuvenn KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Ministry of Basic, Higher and Technical Education School-Based Assessment For S.Y. 2019-2020Dokument23 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Ministry of Basic, Higher and Technical Education School-Based Assessment For S.Y. 2019-2020Sohra MangorobongNoch keine Bewertungen

- English SbaDokument5 SeitenEnglish SbaBritney WoolleryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Preventive Methods in Obstetrics, Maternity Cycle & Maternal and Child Health ProgrammeDokument22 SeitenIntroduction To Preventive Methods in Obstetrics, Maternity Cycle & Maternal and Child Health ProgrammeShivani ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Murray Stein Self TransformDokument140 SeitenMurray Stein Self TransformValeria Almada100% (1)

- Mta Iso FormDokument6 SeitenMta Iso FormSean HooeksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amit SAP103 Assessment 3Dokument10 SeitenAmit SAP103 Assessment 3kimutaigeofry048Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 10 Social Relationships in Middle and Late AdolescenceDokument15 SeitenModule 10 Social Relationships in Middle and Late AdolescenceJerous BadillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eastwood (East Renfrewshire) Registered Childminders 2018Dokument4 SeitenEastwood (East Renfrewshire) Registered Childminders 2018ER ChildmindersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ielts Speaking TestDokument30 SeitenIelts Speaking TestangereminoNoch keine Bewertungen

- English For MidwiferyDokument9 SeitenEnglish For MidwiferyRetno AW100% (3)

- Immunization and PregnancyDokument1 SeiteImmunization and PregnancySANANoch keine Bewertungen

- Infographic Breastfeeding PDFDokument1 SeiteInfographic Breastfeeding PDFIsmatul MaulahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Childhood Education EffectsDokument3 SeitenEarly Childhood Education EffectsaslankadirNoch keine Bewertungen

- DEPARTMENT OF PEDIATRIC Letter Pad DR MUAVIA TAHIRDokument1 SeiteDEPARTMENT OF PEDIATRIC Letter Pad DR MUAVIA TAHIRMohammad ShafiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Childhood Screen III: 0-35 MonthsDokument55 SeitenEarly Childhood Screen III: 0-35 MonthsHoney Patel100% (3)

- Symphonic 2023Dokument6 SeitenSymphonic 2023Muthya Aulina FahriyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acta 12 ¿Vanishing Youth...Dokument615 SeitenActa 12 ¿Vanishing Youth...ajmm1974Noch keine Bewertungen

- Brigance Early Childhood Screen III F&1Dokument1 SeiteBrigance Early Childhood Screen III F&1Sakura ResmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic Prensentation ON: Kangaroo Mother CareDokument15 SeitenTopic Prensentation ON: Kangaroo Mother Careamit100% (1)

- State duty protect children recruitment harming educationDokument4 SeitenState duty protect children recruitment harming educationMyles LaboriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Promoting Baliguian RHU as a Mother-Friendly Health FacilityDokument11 SeitenPromoting Baliguian RHU as a Mother-Friendly Health FacilityAnsams Fats100% (2)

- Tabel EBM Manfaat Pijat Berdasarkan LuaranDokument5 SeitenTabel EBM Manfaat Pijat Berdasarkan LuaranGregory JoeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intellectual Development: Birth To Adulthood, Robbie CaseDokument3 SeitenIntellectual Development: Birth To Adulthood, Robbie CaseWill RudyNoch keine Bewertungen

- MCN Principles of Growth DevelopmentDokument13 SeitenMCN Principles of Growth DevelopmentBenjamin MagturoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Toys and Postwar American CultureDokument29 SeitenEducational Toys and Postwar American CultureSarah HearneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workplace Observations Assessment Task 3Dokument2 SeitenWorkplace Observations Assessment Task 3Joanne Navarro AlmeriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Parentification On Children's Psychological Adjustment: Emotion Management Skills As Potential Underlying ProcessesDokument136 SeitenThe Impact of Parentification On Children's Psychological Adjustment: Emotion Management Skills As Potential Underlying ProcessesgilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Planning Counselling EssentialsDokument15 SeitenFamily Planning Counselling EssentialsOkky isNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Months Well Child CheckDokument3 Seiten2 Months Well Child CheckJanelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Erikson: Trust vs Mistrust ScreeningDokument7 SeitenErikson: Trust vs Mistrust ScreeningMaikel LopezNoch keine Bewertungen